Introduction

The USA has the highest incarceration rate in the world [1], with one in three people having been arrested [Reference Goggins and DeBacco2]. Disparities exist by race and income level with cycles of incarceration plaguing low-income communities of color that exacerbate intergenerational poverty [Reference Nellis3]. Importantly, over 95% of people incarcerated will return to the community [Reference Alarid, Sims and Ruiz4].

Individuals who are incarcerated experience high rates of untreated chronic disease, mental health problems, and substance use disorders (SUDs) [Reference Davis, Bello and Rottnek5,6]. While jails and prisons may be the only setting where individuals have the federal right to not have healthcare deliberately withheld, there are significant barriers to receiving evidence-based care in correctional settings [Reference Olson, Khatri and Winkelman7]. For example, there is no mandatory healthcare accreditation for correctional facilities and even facilities who have undergone voluntary accreditation are not always compliant with healthcare standards [Reference Gibson and Phillips8]. In addition, there is significant variation in healthcare practices at the county and state level [Reference Davis, Bello and Rottnek5,9]. Finally, the availability, quality, and types of reintegration (reentry) programs, that in part address healthcare needs, vary widely, and their effectiveness is largely unknown [Reference Berghuis10].

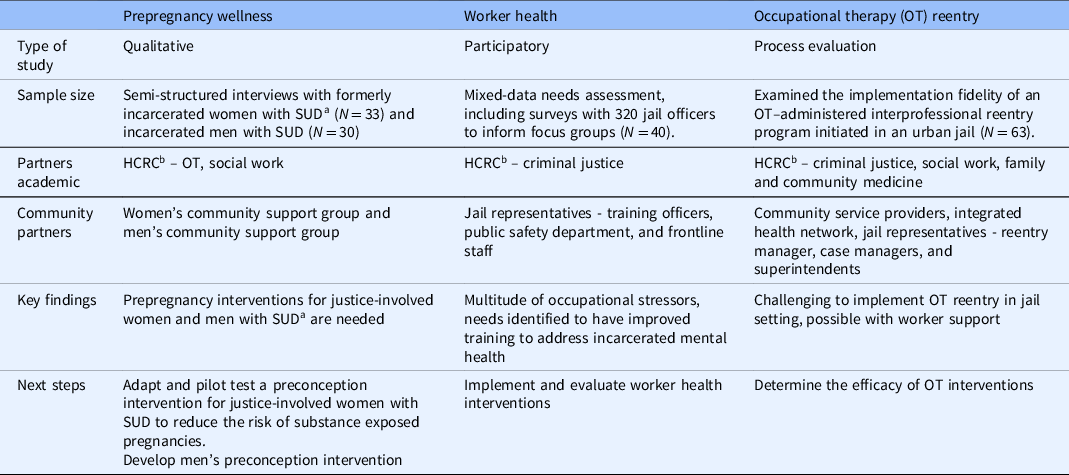

Due to the restricted settings where incarcerated individuals reside and receive services, they are often invisible to the public, leaving policymakers and healthcare professionals with a limited understanding of the needs of this population that has been marginalized [Reference Farrell, Young, Willison and Fine11]. Professionals who provide services in correctional settings are allowed a unique glimpse into the numerous unmet needs of this population. The authors’ goal is to understand and compare the process of identifying an unmet need in correctional settings and then developing and conducting research in this traditionally restrictive environment. To do this, we describe three case examples of how the authors’ observations in correctional settings in the Midwest USA led to interdisciplinary research and community partnerships to address the unique health and social needs of incarcerated individuals. Through these partnerships, exploratory research of women and men’s prepregnancy health needs, Total Worker Health® interventions, and studies of reentry programming were created and implemented in various correctional settings (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). We go on to discuss the clinical and policy implications of these projects, and finally limitations and challenges to research in correctional settings, including the impact of the SARS-COVID 2 pandemic.

Fig. 1. Moving from observations to research and interventions to improve health and policy in correctional settings.

Table 1. Three examples of research/interventions in correctional settings

a SUD: Substance use disorders.

b HCRC: Health Criminology Research Consortium.

Methods

The authors include three unique case examples of their interdisciplinary research in correctional settings that each used a similar approach to identify the need for the research project/intervention, develop professional and community partnerships integral to successfully carrying out the research, and implement the study procedures/intervention [Reference Crowe, Cresswell, Robertson, Huby, Avery and Sheikh12]. First, the authors’ observations in correctional settings in the Midwest USA led to identification of three distinct unmet needs: (1) unmet needs of women of reproductive age were identified during routine clinical care in a correctional health clinic; (2) unmet correctional officer health needs were identified during participation in prison education program in a Midwest US prison; and (3) the need for comprehensive reentry services was identified while exploring the needs of correctional officers identified in observation 2.

Observation 1: Prepregnancy Wellness

While providing primary care in an suburban jail to women of reproductive age, we found that when asked about their pregnancy wishes, many women with SUD and untreated chronic medical and psychiatric problems expressed a desire to become pregnant at some point in the future. The desire for future pregnancy among women who were incarcerated coupled with an increased risk for poor maternal and child health outcomes due to substance use and chronic disease [Reference Floyd, Jack and Cefalo13] prompted us to conduct a review of the literature to identify interventions to help women with SUD optimize their health before pregnancy. We found a lack of interventions for women with illicit SUD in the prepregnancy period [Reference Bello, Baxley and Weinstock14]. Our clinical experience taken together with our identification of a lack of interventions and research in this area prompted us to further explore the concept of prepregnancy wellness with justice-involved women using qualitative methodology.

Observation 2: Correctional Officer Health

In 2014, we toured a prison facility to explore the Saint Louis University (SLU) Prison Education Program that offers an associate’s degree to both staff and people incarcerated, creating the foundation for integrating correctional workplace health and reentry services. During this tour, the extreme stress and challenges faced by correctional officers were highlighted. Furthermore, meetings with a variety of stakeholders with lived experience with justice involvement voiced their needs for reentry planning (also described as reintegration or community transition preparation) with the second author. These discussions led to research projects informed by the voices of the officers and with stakeholders with lived experience [Reference Jaegers, Ahmad and Scheetz15,Reference Jaegers, Skinner and Conners19]. Findings from these studies identified the gap in addressing meaningful work roles among officers and jail or prison residents and led to the development of the SLU Transformative Justice Initiative (TJI). Subsequently, TJI addresses the intersections of criminal justice system health and safety with the prevention of incarceration and preparation for transitions from criminal justice settings (reentry program described in “Observation 3: Reentry Process Evaluation”). In 2016, Jaegers applied the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health (NIOSH) Total Worker Health® (TWH) strategy to perform correctional workplace health needs assessment in urban and rural jails [Reference Jaegers, Ahmad and Scheetz15]. This evidence-based strategy uses an integrated approach to address policies, programs, and practices for workplace health promotion [Reference Punnett, Cavallari, Henning, Nobrega, Dugan and Cherniack16]. We utilized community-based needs assessment within a Midwest urban jail to determine workplace health issues and identify related interventions. We gathered health and organizational fairness characteristics through self-administered surveys (N = 320) and identified institution and interpersonal aspects of the workplace and ideas for workplace solutions through focus groups (N = 40) [Reference Jaegers, Ahmad and Scheetz15]. A subsequent, prospective study assessed changes in health among new corrections officers during their first year of employment [Reference Jaegers, Vaughn, Werth, Matthieu, Ahmad and Barnidge17].

Observation 3: Reentry Process Evaluation

During the implementation of the correctional worker health study (see "Observation 2: Correctional Officer Health"), we learned about the urban jail leadership’s goal to provide reentry services, not previously offered. With a newly developed occupational therapy (OT) model for reentry [Reference Jaegers, Barney, Aldrich, Vaughn, Salas-Wright and Jackson18], we engaged interprofessional and OT advisory teams to consider the design of reentry programming for people incarcerated. Since the workplace health study demonstrated our commitment to support staff and to their facility, we established trust and gained the jail’s support for implementing an OT Transition and Integration Services (reentry) program (OTTIS). The OTTIS program was launched in 2016 with funding by the local jail and continues with full-time staff and support by students from OT, social work, and public health. The program is unique for working with individuals in jail and continuing services after release to the community. To determine program feasibility, we performed a process evaluation to track occurrence and duration of OT activities, participant attendance, completion of homework, and barriers and facilitators (gathered during weekly OT team meetings) [Reference Jaegers, Skinner and Conners19].

Interdisciplinary Research Partnerships

During the course of these projects, the authors became connected through various correctional settings and utilized their complementary expertise and lenses to understand the significant gaps in care for incarcerated individuals. To help inform and advance their work in correctional settings, the authors joined the Health Criminology Research Consortium (HCRC) that brings together researchers across disciplines both within their institution and nationally who focus on studying the intersection of health and criminology to address the physical, mental, and social needs of incarcerated individuals to influence policy and health outcomes among populations who have been traditionally marginalized [Reference Vaughn, Jackson and Testa20]. Researchers in the HCRC offer statistical support, mentorship, and collaborations.

Community Partnerships

Women and Men’s Health Partnerships

Through her clinical work in corrections medicine, Bello became connected with local nonprofit organizations that helped inform and conduct qualitative studies to explore justice-involved individuals’ experiences and perspectives on prepregnancy wellness. First, Bello connected with a nonprofit organization that provides justice-involved women with weekly support groups and parenting sessions. Bello used pilot funding awarded from a local university to recruit 33 formerly incarcerated women, 22–62 years old, from this organization to participate in interviews to share their experiences and perspectives about their decision-making about health before and during pregnancy as it relates to substance use and incarceration. The study methods are published elsewhere [Reference Bello, Johnson and Skiold-Hanlin21].

Next, Jaegers and Bello were awarded an institutional pilot grant to partner with a nonprofit organization that provides a 6-week immersion program for men with criminal justice involvement living in transitional housing that teaches the necessary skills for effective parenting and prevention of problematic substance use prior to release into the community. The authors recruited 30 men with SUD from this program to participate in virtual semi-structured interviews between June and September 2021. Questions rooted in the constructs of the Health Belief Model (HBM) [Reference Rosenstock22,23] were asked to understand (1) constructs that facilitate men’s substance use while romantic partners have a chance of or are currently pregnant, (2) barriers to stopping or limiting substance use around romantic partners, and (3) recommendations for intervention components to address men’s substance use behaviors in the context of romantic relationships. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a transcription service. Two researchers independently analyzed the transcripts using qualitative software to identify statements that align with constructs from the HBM to create codes. The codes were then organized into larger categories that represent themes that emerged from the data inductively through a grounded theoretical approach [Reference Corbin and Strauss24]. Coded transcripts were reviewed and assessed for inter-reviewer agreement. Discussion among all five investigators resolved inconsistencies.

Worker Health Partnerships

At the level of jail organizations, the worker health projects at correctional facilities required partnerships with multilevel representatives, including frontline officers, case workers, training academy officers, supervisors, and majors. Furthermore, engaging local city departments such as public safety was very helpful for project advocacy.

Local partnerships that resulted from the TJI projects included partners with OTTIS, Integrated Health Network, jail, police department, court division, and a variety of community service providers in mental health and housing. With these diverse partners, we developed the Community Resources and Needs Screen (CRANS) to determine the needs of individuals in the pre-sentencing phase within 48 hours of entering jail booking. CRANS helped to identify social determinants of health needs, including housing, mental health services, food, and transportation. The goal was to share the CRANS with the client’s attorney for the purpose of advocating for their needs during their pretrial hearing – a time when many are held in jail on cost-prohibitive bail. This advocacy was intended to link clients with services prior to their sentencing court date, so they may participate in needed treatment, employment, or other services to prevent long-term incarceration.

At the national level, in 2014, Jaegers developed a partnership with the National Corrections Collaborative (NCC), a working committee to advance research and workplace health promotion for correctional worker populations by bringing together correctional leaders, researchers, and professionals in health and criminal justice from across the USA to support research to practice [Reference El Ghaziri, Jaegers, Monteiro, Grubb and Cherniack25]. The NCC partnership led to a study funded by the National Institute of Corrections to move from understanding the health disparities in corrections work to investigate the available resources to address workplace trauma and organizational stress in jails and prisons.

Reentry Partnerships

A wide variety of partnerships formed to support the OTTIS reentry project. Together with the larger community of service providers, we sought knowledge and support to provide related services for people justice involved. For example, Bello and Jaegers collaborated to implement preconception programs for women and men participating in the OTTIS program. The Transformative Justice Initiative Reentry Program prepregnancy module (see "Transformative Justice Initiative Reentry Program Pre-pregnancy Module") included an assessment of women’s pregnancy intentions and feedback on both the women’s and men’s program content.

Due to her leadership of the OTTIS program, Jaegers was invited to be a task force member with the Integrated Health Network’s Reentry Community Linkages (RE-LINK) to problem-solve with other community service providers post-release reentry services coordinated by RE-LINK. Offering support as a Steering Committee Member for a local Alliance for Reentry, Jaegers assisted with the strategic planning along with area service providers and representatives from state corrections, probation and parole, mayor’s office, and health and public safety departments. Additional committees have sought Jaegers’ collaboration including Alternatives to Incarceration and Family Treatment Court.

Results: Research Findings and Interventions from Each Project

Women and Men’s Prepregnancy Wellness

Transformative Justice Initiative Reentry Program Prepregnancy Module

The women’s program was well received, and 52% of participants from five sessions (N = 48) wanted to become pregnant at some point in the future and indicated that the program would motivate them to stop illicit substance use to have a healthy pregnancy. Early findings with two men’s cohorts (N = 11) were promising. Most participants (N = 10) wanted to know more about how their substance use could affect the health of their future children. All participants (N = 11) wanted to know how a man’s support of his partner during pregnancy could improve the health of a pregnancy and children. These findings support that justice-involved men are interested in understanding how their behaviors influence those of their partner.

Qualitative Study: Perspectives on Prepregnancy Health among Formerly Incarcerated Women with SUD

The following themes were identified (N = 33): (1) lack of awareness of how stopping substance use before pregnancy can improve outcomes; (2) the importance of internal motivation to stop drug use while pregnant; and (3) challenges in planning a pregnancy or making behavior change while actively using drugs. For example, one participant described how her focus on obtaining her drug of choice did not allow her to consider the consequences of having unprotected sex: “When you’re in your addiction nothing or no one matters. Your addiction matters… I don’t think that you think about the consequences…and I do not think that nobody… feel like, ‘I better not get pregnant while I’m using,’ because…when you using, you’ll go to any length to get that drug.” The complete study findings are published elsewhere [Reference Bello, Johnson and Skiold-Hanlin21].

Qualitative Study: Perspectives on Substance Use, Relationships, and Pregnancy among Justice-involved Men with SUD

Study participants (N = 30) described being aware of the negative effects of substance use on pregnancy outcomes. However, awareness of risks did not necessarily lead to change in substance use behavior due to several barriers including (1) participants describing living in the moment and not considering stopping substance use, (2) the perceived impact of how stopping substance use would negatively affect their romantic relationship, and (3) persistent use to cope with mental health issues. Participants described resources that could support men in addressing their substance use to better support their romantic partners before and during pregnancy including peer support specialists and SUD support groups.

Correctional Workplace Health

Survey findings indicated high levels of health disparities among correctional officers as compared to studies of other workforces in the areas of depression and Post-traumatic stress disorder [Reference Jaegers, Matthieu, Vaughn, Werth, Katz and Ahmad26,Reference Jaegers, Matthieu, Vaughn, Werth, Katz and Ahmad27]. Focus group findings indicated suggestions to address workplace culture and communication (e.g., appreciation, treatment by coworkers and management, accountability, and respect), training and safety (e.g., staffing support, annual follow-up, new training topics such as self-defense, behavioral and mental health, and safety equipment), and community (e.g., working with community-based health resources and the public’s perception of correctional officer work) [Reference Jaegers, Ahmad and Scheetz15].

Reentry Program

Using session logs to document sessions, start and end times, and receipt of homework, the OTTIS reentry process evaluation indicated that 93% of planned OT activities occurred, duration of sessions fell short of anticipated/scheduled timing, and homework completion rate was 92%. The review of meeting notes revealed barriers in the areas of policy (e.g., inability to plan for unexpected and unknown release dates), community-level barriers to mental health and SUD services, and housing supports (e.g., limited capacity of service providers and shortage of housing options), individual violations of jail rules, and institutional operations (e.g., restrictions in movement of people within the facility) that limited attendance. Facilitators were most prevalent among correctional officers who identified the SLU OT program as a partner in both worker health and reentry, and a variety of university interprofessional partners who informed the program and provided additional support.

Discussion

While there are countless unmet needs and opportunities for meaningful research with the potential to improve the physical and mental health of incarcerated persons, researchers may face barriers in conducting research in correctional settings. These three diverse projects utilized a common approach to address unmet needs of correctional populations and can serve as a guide for researchers who are interested in conducting research in correctional settings as well as those who have faced challenges in conducting research in this setting. The authors built trusting relationships with interdisciplinary academic partners and community organizations allowing them to carry out formative pilot studies and novel programs with the potential to improve the health of justice-involved individuals. Findings from the qualitative study with women with SUD directly supported an awarded National Institutes of Health career development grant to adapt and pilot-test a preconception intervention to enhance intrinsic motivation to initiate and persist in behavior change to address substance use in women undergoing treatment in a jail-based SUD treatment program. Findings from the qualitative study with men will inform development of an intervention for justice-involved men with SUD to address substance use in the context of romantic relationships. This parallel exploration with justice-involved women and men with SUD will ultimately lead to an intervention that considers the unique perspectives and reproductive health needs of both justice-involved women and men.

The programs within the TJI continue to grow, and outputs generated for dissemination with a variety of audiences. For instance, the OTTIS program is internationally recognized as a leader and innovator in correctional reentry. Jaegers has facilitated a grassroots network called Justice-based OT (JBOT) to advocate for occupational engagement/participation and health for those within and/or impacted and/or at risk for involvement with the justice system (staff, persons incarcerated, families and friends, and employers), to further societal wellbeing. We will continue to evaluate our reentry services in larger studies. Finally, the workplace health studies expand upon the limited literature that exists focusing on holistic approaches to integrate workplace health with incarcerated resident activities that have been the focus of a recent culture shift among correctional leaders [Reference Jones Tapia28]. Our workplace health studies will continue to explore the direct links between corrections work and impact on justice-involved individual’s community reentry.

An interdisciplinary approach is needed to understand, develop, and test interventions and programs to address the complex health and social needs of justice-involved individuals. To gain a more balanced and comprehensive understanding that takes a person’s whole social, community, medical, and mental health needs into account, perspectives from multiple disciplines are needed [Reference Repko and Szostak29]. Looking at incarcerated individuals’ needs in isolation is inadequate because it does not take into account the health and social drivers that impact an individual’s current situation and likelihood for successful transition back into the community [Reference Berghuis10]. Acknowledging and identifying ways that address factors such as the social environment that influenced the circumstances of justice involvement and barriers that will be faced in integrating back into society is essential.

Development of community partnerships is key to working with justice-involved populations, because there are numerous organizations with deep connections in local communities that can provide not only insight into the needs of this population but also serve as a resource for recruiting justice-involved participants who could benefit from participation in study interventions. Importantly, creating sustainable community partnerships is essential to understand the needs of incarcerated individuals that considers the historically rooted disparities in justice involvement experienced by people of color [Reference Boghossian, Glavin and O'Connor30]. By partnering with and listening to leaders in the community, research and interventions can align with the goals and needs of communities that have been impacted by criminal justice involvement rather than run the risk of exacerbating disparities [Reference Farrell, Young, Willison and Fine11]. In addition, support from community leaders helps to build trust with potential program and research participants. Finally, it is important to disseminate what has been learned back to community partners in a process of re-evaluating and improving current projects and sustaining partnerships.

Research involving individuals defined as “prisoners” requires additional levels of protection and oversight as defined by the Office for Human Research Protections [31]. Specifically, due to the unequal power dynamics between incarcerated individuals, researchers, and institutions, research projects must meet a high level of specific standards. For Institutional Review Boards (IRB) that are not familiar with human subject’s research with prisoners as subjects, there may be challenges in the IRB review process that can delay or even prohibit research from moving forward as planned [Reference Watson and van der Meulen32]. However, understanding the regulatory issues, maintaining flexibility, and working closely with your institution’s IRB can lead to successful research programs and interventions that have the potential to increase our knowledge of and address the unique needs of justice-involved individuals while protecting the rights of research participants.

The SARS-COVID 2 pandemic both highlighted and exacerbated issues within correctional settings that negatively impacted the health of incarcerated individuals and staff while also inhibiting research and halting even well-established programs. Jails are settings where residents cycle in and out of the community, being held for minor offenses or waiting hearings. The high turnover in this setting has been linked to the spread of COVID-19 in surrounding communities [Reference Reinhart and Chen33]. Changes to limit disease transmission vary widely because they are dictated by local policy in the form of legislation, executive orders, court orders, policy changes, and prosecutor discretion [34]. To limit the spread of COVID-19 within correctional facilities, many jails and prisons placed restrictions that allowed only essential workers and visitors to enter facilities. In some cases, this shut down programs that were deemed unessential, including Jaegers’ reentry program that was transitioned to a virtual format and the CRANS which was placed on hold. In addition to restrictions on visitors and programs, there were constraints on movement of residents within the facility that ultimately negatively impacted the mental and physical health of residents. Finally, the correctional setting has also been impacted by significant staffing shortages that have led to additional movement restrictions and safety concerns.

Limitations/Challenges

While challenges to carrying out intervention research in correctional settings are numerous, they are not insurmountable. For example, changes in leadership within organizations, service agencies, and city/county/state leadership can create barriers or opportunities for partnership. Considering charters, memorandum of agreement, or other contracts to ensure carry through from one leader to another are necessary to prevent the program from ending when the baton is passed. While our projects show a wide variety of partners, the list of potential partners is likely never exhausted and a good faith effort is needed to ensure the needed linkages have been attempted. Other challenges include having limited access to the population, restrictions on research that make it difficult to carry out prospective human subjects’ primary data collection, staffing shortages, and impacts of the pandemic. With strong partnerships and trusting relationships with staff and administration, alternative ways to carry out projects that will ultimately lead to interventions and policies to address the needs of correctional populations can be done successfully. Patience and persistence are key. Finally, while we work within correctional settings in the Midwest USA, we believe our experience and study findings are useful for individuals both working in and conducting research in correctional settings in other areas of the USA.

Conclusion

We presented three diverse case examples which were designed to address the health and social challenges of people justice involved and identified (1) the need for prepregnancy interventions for justice-involved women and men with SUD, (2) a multitude of occupational stressors and needs to have improved training to address incarcerated mental health, and (3) challenges in implementing OT reentry in jail settings that could be overcome with worker support. While these three examples are distinct, they each follow a similar process of being immersed in a correctional health setting and building trusting relationships among key stakeholders. Using an interdisciplinary approach, they relied on numerous academic and community partnerships to carry out the research and interventions. Identifying needed partnerships among the target population, local community, and peers in academia are essential to performing community-based research with correctional populations who have complex health and social needs. These partnerships take time to develop and establish trust for long-term sustainability. Addressing community health and the many types of partners who may be involved is essential to identifying critical research questions for future study that directly consider current and future issues of the population. Community-based research projects that begin small have the potential to grow many lines of inquiry and expand to broader partnerships essential to meaningful study. They are necessary to demonstrate feasibility and efficacy for the support of larger projects that can inform policy change. Finally, the unmet health and social needs of justice-involved individuals are vast. Developing sustainable community and research partnerships allows a unique opportunity to develop, implement, and test needed interventions.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation and thanks to the correctional workers and justice-involved individuals at participating jails and prisons. We express gratitude and appreciation for the many community partners for their collaboration; and from Saint Louis University, Dr. Karen F. Barney and Kenya Brumfield-Young for their guidance and leadership in programming; and Dr. Michael Vaughn of the Saint Louis University Health Criminology Research Consortium who provided editorial help and critical comments during the preparation of this manuscript. The prepregnancy health research was funded by Lindenwood University’s Hammond Institute’s Criminal Justice Reform Initiative Seed Grant Program (J.K.B.) and Saint Louis University’s Applied Health Sciences Research Grant Program (J.K.B and L.A.J.). J.K.B was also supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number: K23DA053433. The workplace health projects were supported, in part, by pilot project grants from the Healthier Workforce Center of the Midwest (HWC) at the University of Iowa. The HWC is supported by Cooperative Agreement No. U19OH008868 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC, NIOSH, HWC, or participating sites (L.A.J). All research protocols were approved by the Saint Louis University, Institutional Review Board.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.