Body well nourished; mucous membranes pale; no hair on pubes; breasts beginning to be prominent but not yet developed. … Vagina smooth and dilated; no hymen or fourchette, and no ruga. A longitudinal tear 1¾ inches in diameter in the cellular tissue of the pelvis. Vagina, uterus and ovaries underdeveloped. No sign of ovulation.

Upon opening up the body, one saw that only the epididymis of the left testicle had passed through the ring; it was smaller than the right one. … Two ejaculatory canals, one on each side of the vagina, protruded from beneath the mucous membranes of the vagina and traveled from the vesicles to the vulvar orifice. The seminal vesicles, the right one being a little larger than the left, were distended by sperm that had a normal consistency and color.

The first of the epigraphs is taken from the autopsy of eleven-year-old Phulmoni Dossee who died in Calcutta in 1889 following what were euphemistically described as “injuries inflicted on her wedding night.” Medical experts verified that severe injuries sustained during forced sex with her husband were the cause of death. The details of her brief life are lost to the historian, but the autopsy report remains the most scrutinized of such documents from India. In the 1890s, the report was widely circulated among members of the Viceroy’s Legislative Council in India, in the press, in medical textbooks, and in public meetings, as the case fanned efforts to raise the age of consent within and outside of marriages to better protect girls such as Phulmoni Dossee. Indeed, the law member of the Viceroy’s Legislative Council, Andrew Scoble, gave the case a place of prominence in his initial arguments for amending the law, suggesting that “the feeling which this case is likely to excite in both European and Native circles will afford a good opportunity for raising the age of consent from ten to twelve years.”Footnote 3 The case reinvigorated the debate on the piteous state of child wives while bringing new attention to the anatomical body as a focus of humanitarian sentiment.Footnote 4 Historians agree that the death of the “child” cut through the lethargy of a colonial bureaucracy reluctant to intervene in matters of religion and paved the way for a change to the law.

The second autopsy, well known to historians of sexuality, was conducted twenty years earlier on the corpse of Abel Barbin, a clerk in the Parisian railroads, discovered by a local police commissioner and a state physician in a sparse attic following his suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. To verify whether the youth had been driven to death by the effects of syphilis, the state physician proceeded to check his genitalia, only to find a “strange mélange of sexual anatomy: a short imperforate penis, curved slightly backward and pointed towards … a vulva – labia minora and majora, and a vagina large enough to admit an index finger.”Footnote 5 These conflicting signs had, in fact, been carefully scrutinized eight years earlier, when Abel had sought help from both priests and doctors. Born Herculine Alexina, female, on November 8, 1838, as the birth records indicated, Abel had lived the first twenty-two years of her life as a female, raised in a convent, and employed in an all-girls boarding school. With the discovery of the genital “anomalies” later noted in the forensic report, her legal and public identities had then been “rectified” in keeping with her anatomy, to preserve the distinction between the sexes in the medical, legal, and social senses. As Michel Foucault first demonstrated, dead or alive, Barbin’s body, and the puzzle it posed, is indicative of a wider transformation in biomedical understandings of sex: no longer concerned with identifying the juxtaposition or intermingling of the two sexes to determine which prevailed over the other in an individual, experts became concerned “with deciphering the true sex hidden beneath ambiguous appearances.”Footnote 6 Barbin’s case testifies to the new entanglement of biomedical truth and legal personhood, the anatomization of juridical reasoning, and the construction of embodied “truths” themselves and has been crucial to critical inquiries into sex, gender, and the body made in the wake of Foucault’s intervention.Footnote 7

The two cases, separated in time and space, share the form in which they enter history: that of autopsy reports that incited posthumous debates based on the assumption that bodily signs contain the “truth” of legal identity. They capture how the body itself was seized upon as the site for the expression of, and possible solutions to, wider social crises. Herculine’s body, which failed to fit into the “binary classification of man or woman, forced observers and experts to admit presuppositions regarding the categories male and female.”Footnote 8 These experts debated which signs were to be privileged in classifying bodies as truly male or female: the relative size of the penis or clitoris, the depth of the vagina, the patterns of hair growth, the gait, the timbre of the voice, the shape of the pelvis, or the gonads. Similarly, I would argue, confronted with the ambiguous signs appearing on Phulmoni’s body – hairless pubes, protruding breasts, underdeveloped ovaries – doctors and legislators were forced to ask analogous questions: Was an eleven-year-old a child or woman? Confronted with conflicting signs, doctors grasped for the criteria to be used to secure the boundary between children and women.

While feminist scholarship now takes for granted the social construction of sex, the faith in the nature of childhood has proved intractable. This chapter stages a strange encounter between two seemingly disparate cases to read Phulmoni’s case sideways, that is, to leave behind the conventional account of it as providing an opportunity to effect an ultimately progressive (if somewhat limited) alteration to the age of consent in colonial India. In placing Barbin’s case side by side with that of Phulmoni, this chapter identifies the autopsy as a source for an analogous quest for the “truth” of childhood and uses the familiar illustration on the social construction of sex to comprehend the historical constitution of both childhood and age. This juxtaposition also serves as a reminder of this book’s point of departure, namely, that the child is an object constructed by sex, in the sense that it is one of the key figures around which sexual norms are defined in modern societies.

Understanding that the “possibilities for truth, and hence of what can be found out, and methods of verification, are themselves molded in time,”Footnote 9 this chapter studies the autopsy as a key technology by which the child was “made flesh” in late colonial India. In doing so, it traces the emergence of the autoptic child, a quintessential object without history: both determinable by forensic scrutiny and self-evident through personal observation.Footnote 10 The term serves as a heuristic to straddle a conventional distinction made by historians between the “flesh and blood” children living at distinct points of time through history and the corresponding ideas of “childhood” recognized to be a matter of social construction.Footnote 11 The concept also serves to clarify why feminist (and queer) theory, so careful in acknowledging the historical construction and cultural signification of the category “woman,” perpetuates the naturalization of the child.Footnote 12

This chapter sidesteps the conventional historical account in which the Age of Consent Act is understood to be a precursor to the Child Marriage Restraint Act (CMRA) of 1929. Approaching the 1891 Act sideways, and armed with the skepticism toward straight time that is the hallmark of this method, this chapter grapples with the temporality of the law itself. It explores the ways in which law’s organization of time with reference to legal capacity renders the “child” as a natural category. It shows the ways in which age, which is but an expression of law’s temporality, is, in turn, represented as natural in being indexed to bodily developments. The first of three sections traces how, during the debates on the age of consent, the constant reference to the physiological body helped to turn age itself – long considered as an artificial, arbitrary, yet convenient signifier of capacity in the law – into an embodied fact. This historical constitution of age as an embodied fact becomes clearer in contrasting the discussions on the age of consent with those on the age of majority and the minimum age for laboring in factories, as explored in the second section. The final section revisits feminist scholarship on the age of consent to suggest that in subscribing to the law’s temporality, this scholarship operates as yet another technology – along with law and medicine – that renders the child autoptic. In reading sideways, and thus rejecting a notion of time that is always moving forward toward a future, we can move beyond debating the notion of “consent” – which has been the staple in much feminist scholarshipFootnote 13 – to a radical questioning of the use of age as its measure. We can begin to recognize how law’s temporality is manifested in the form of an epistemic contract on age – an implicit agreement that age is a natural measure of legal capacity for all humans.

1.1 Law’s Body: Translating “Puberty” Into the “Age of Twelve”

The limit at which the age of consent is now fixed favours the premature consummation by adult husbands of marriages with children who have not reached the age of puberty, and is thus, in the unanimous opinion of medical authorities, productive of grievous suffering and permanent injury to child-wives and of physical deterioration in the community to which they belong. It has, therefore, been determined to raise the age of consent to twelve.Footnote 14

In a brief memo to the viceroy of India, Lord Lansdowne, on July 6, 1890, Andrew Scoble, who took the lead to push through the Age of Consent Act of 1891, reported on Phulmoni’s case to suggest the time was ripe for a change to the age of consent in India and that prepubertal consummation of marriages could be prevented by raising it from ten to twelve years of age. In the months that followed, the case would be extensively circulated and cited within the Legislative Assembly and without, as evidence of “one of the worst features of the Hindu social system,”Footnote 15 leading to the enactment of Scoble’s bill on March 19, 1891. Phulmoni’s body was circulated as proof of the horrifying and common consequences of premature sex with child wives. Described in expert circles as “a notorious case [that] attracted medical notice and led to the act raising the nubile age from ten to twelve years,”Footnote 16 it was represented as the immediate cause behind the passage of the Age of Consent Act. The case was widely cited in the press throughout British India.Footnote 17 It was evoked to great effect during meetings held by various medical societies that debated the “physiological grounds” upon which the new age of consent would rest.Footnote 18 Meanwhile, doctors opposed to the bill – and there were many – pronounced Phulmoni’s case a “medical anomaly.”Footnote 19 Phulmoni’s body thus simultaneously served as the site for the diagnosis of Hindu social ills and for the determination of the “true” signs of “childhood” and “maturity.”

Significantly, it also served to translate a cluster of bodily events broadly understood as “puberty,” perceived to be tied up with the messiness of individual and racial difference, into the neat and universal form of the chronological age of twelve. Amid the outrage provoked by Phulmoni’s death, Scoble proposed a modification to the existing rape law to protect “children who have not reached the age of puberty.”Footnote 20 Introducing the Indian Penal Code and Code of Criminal Procedure, 1882, Amendment Bill in the Legislative Council of the governor general on January 9, 1891, Scoble suggested that raising the age of consent from ten to twelve years would facilitate its “two-fold” object: “to protect female children (1) from immature prostitution, and (2) from premature cohabitation” while effecting an improvement “in the physical and social well-being of the people at large.”Footnote 21 If Scoble thus envisioned his bill as automatically protecting children, what made the “age of twelve” the boundary between the child and the woman? How did the bodily developments associated with puberty come to be designated by a precise chronological age? Scoble’s phrase – “children who have not reached the age of puberty” – may be read in two ways: either he aimed to protect children only until the age they attained puberty or he intended to suggest that childhood ended when puberty began. In either case, Scoble foregrounded “puberty” as a significant marker of transition from childhood to womanhood. While the age of consent – hitherto set at ten and perceived as a legal convention dissociated from bodily facts – thus came to be naturalized in becoming attached to a bodily event, medical experts barely agreed on the correspondence between the biological fact of “puberty” and a specific chronological age. Moreover, it was not “puberty” at all but the age of twelve that was to be enshrined as the boundary between the child and the woman. In other words, even though chronological age was but an imperfect proxy for physiological development, it was treated as intrinsically significant.

In some ways, Phulmoni’s case provided a perfect rationale for the new convention, that is, the age of twelve as the age of consent. According to her maternal grandfather’s testimony, she had been eleven at the time of her death (later modified to a more precise, “10 years three months”).Footnote 22 The inspector of police from Puddopookur Thana confirmed this statement of age: the girl’s paternal grandfather had indeed registered the “birth of an unnamed girl born on 3rd of March, 1879.” It was clear she was above the age of consent at the time, and during the trial, medical experts looked to physical signs of maturity to determine whether or not Hari Maiti ought to have been aware of the harm he might cause. They pointed to the conflicting signs of physical maturity, including the presence of hair in parts of the body, the development of breasts, and the state of the vaginal passage. Dr. Cobb, the police surgeon who examined Phulmoni’s body immediately after her death, reported:

I came to the conclusion that she was between 11 and 12. The body was well nourished. I found a blood-stained cloth around her waist and between her legs. I came to the conclusion she had not attained puberty. The uterus and ovaries were underdeveloped and she had not menstruated. The growth of hair on the part is one of the signs of puberty, I saw no sign of any.Footnote 23

During the cross-examination he struggled to explain the relevance of various bodily signs: “The breasts of Phulmoni were beginning to be prominent; the beginning of prominence is not a sign of puberty; when they are more or less developed, it is.” Drs. Joubert and McLeod – both prominent medical doctors and professors at the Calcutta Medical College – served as expert witnesses, pointing to conflicting signs on her body and commenting on the true and false signs of puberty. In the end, all doctors agreed in declaring that Phulmoni’s body had been “immature” or prepubertal by various criteria.

What is apparent, however, is that doctors did not discover any facts in the body that made it necessary to correct the misrecognition of Phulmoni’s true status as a “child.” To paraphrase Judith Butler on Barbin, Phulmoni could “never embody that law precisely,” for she could not provide “the occasion by which the law naturalizes itself in the symbolic structures of anatomy.”Footnote 24 While medical experts debated the signs of puberty and maturity that could be privileged to shore up the law’s binary distinction between child and woman, in opening up Phulmoni’s body, medical experts certainly did not discover a rationale to raise the age of consent to the age of twelve as Scoble claimed. In the end, then, what was the rationale for settling on the age of twelve?

The “age of twelve” had a long history in reformist circles. The Native Marriage Act of 1872 had established twelve as the minimum age of marriage for Brahmo females.Footnote 25 At the time, insisting that the question of child marriage and its “religious bearings must be determined by the verdict of physiology,” the Brahmo leader Keshub Chunder Sen had sought Bengali doctors’ opinions on the effect of climate and other factors in order to determine the “earliest marriageable age consistent with the well-being of mother, child and society,” to arrive at a suitable age of marriage “on true physiological grounds.”Footnote 26 Decades before this effort, a Manchester-based surgeon, John Roberton, had drawn on a range of general histories, ethnographies, medical texts, and medical and missionary correspondence to pronounce the age of twelve as the average age of puberty in India. His chief informant for Bengal, Dr. Goodeve, professor of midwifery at the Calcutta Medical College, had returned “the average age of puberty” as twelve years and four months based on ninety instances. Allan Webb, professor of military surgery at the Calcutta Medical College, calculated the average age of puberty as twelve years and seven months, based on 149 cases. Webb obtained this information from Modoo Soodon Gupta, an assistant at the Calcutta Medical College. Gupta’s statistics on the age of first menstruation in Bengal, in turn, were based on information gathered from students of the Calcutta Medical College regarding their wives.Footnote 27 These anecdotal and ethnographic studies – which circled back to the age of twelve as the average age of puberty – continued to be cited in 1890–91.

But by the last decade of the nineteenth century, there was less and less agreement that the chronological age of twelve captured any significant bodily developments that could rationalize its selection as the age of consent. In one of the dozen or so responses sent by medical experts to the government of Bengal on Scoble’s proposed changes to the age of consent, Surgeon Major F. C. Nicholson, a civil surgeon at Dacca, cited the aforementioned survey conducted by Modoo Soodon Gupta, Allan Webb’s Pathologica Indica (1848), Norman Chevers’s Medical Jurisprudence for India (1856), along with his “own observations and inquiries” based on 68 cases of first menstruation, of which “49 occurred at 13 and over.”Footnote 28 While Nicholson agreed it was necessary to “fix puberty as the period of life before which consent cannot be given,” he insisted that the higher age of thirteen was more appropriate as the modal age of menstruation in India and that it also had the virtue of being consistent with the extant law in England.Footnote 29 Referring to some of the same sources, Brigade Surgeon H. B. Purves cast doubts on the statistics on “first menstruation” gathered in India, reiterating the suspicions that the reported ages were not an indication of a natural occurrence, and likely records of “a first copulation and the result of injury to parts, or even the result of artificial dilation to prepare a female for marriage.”Footnote 30 Others, such as R. C. Chandra, the professor of materia medica and clinical medicine at the Calcutta Medical College, questioned that presumed equation between the onset of menstruation and the attainment of puberty: “Menstruation is not a sign of a girl having acquired the full capacity for sexual intercourse. It only shows that she has just commenced to enter into this new stage of her development.”Footnote 31 Several experts who concurred with Scoble on the principle that females were to be protected from prepubertal sex no longer appeared to agree that the chronological age of twelve captured the biological fact of puberty.

Following the death of Phulmoni, the president of the Calcutta Medical Society and professor of surgery at the Calcutta Medical College, Dr. Kenneth McLeod, initiated fresh investigations into the “age of nubility” among Indian females, inviting his colleagues to weigh in on a range of questions he considered significant to setting the age of consent: Was sexual maturity alone or a more “general maturity” to be the basis of marriageability? Wouldn’t the individual and the race both suffer the consequences of “productive marriage after sexual maturity, and before the completion of bodily and mental maturity?”Footnote 32 In a paper presented to the Calcutta Medical Society, which he subsequently forwarded to the Legislative Department as they deliberated on the new age of consent, McLeod insisted that recent research indicated that “puberty or sexual maturity is very seldom attained by females in India before 12; and that the period of immaturity demanding legal protection may reasonably be defined and limited by that age.”Footnote 33 This was seized upon by Scoble when introducing the bill as justifying the proposed age of consent.Footnote 34 McLeod’s colleagues, however, were torn not only about the modal age of puberty in India but also about the medical definition of puberty and maturity, and hence proposed twelve, fourteen, or even sixteen as alternatives.

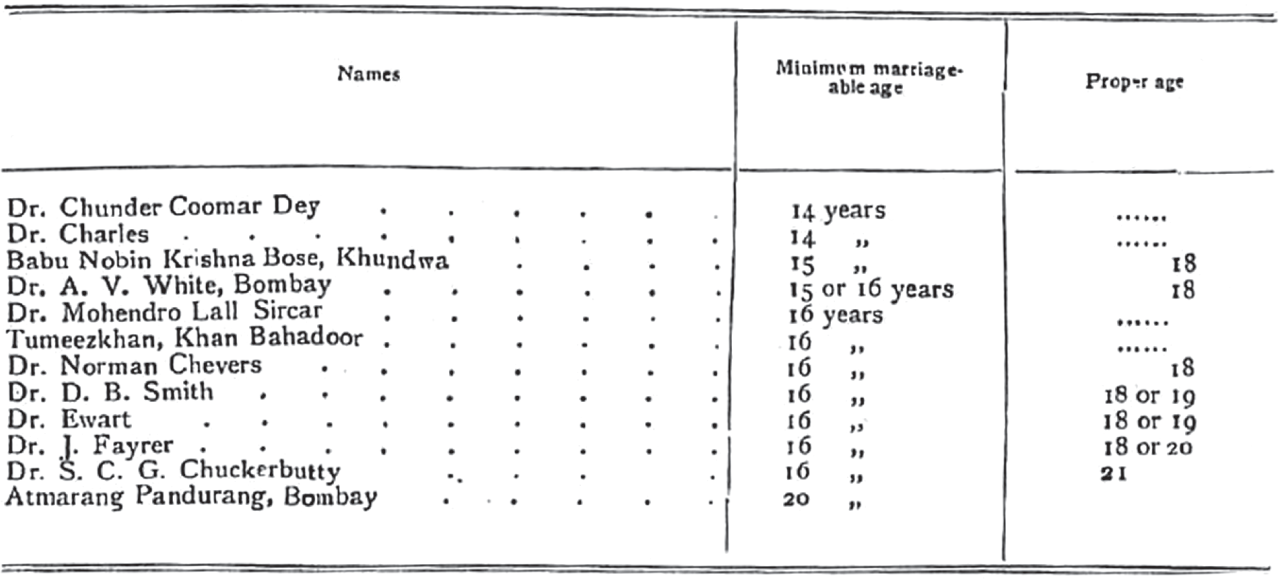

In the most impassioned of the responses to McLeod’s call, a Bengali doctor Boyle Chunder Sen cited a range of sources – ancient Indian legal and medical texts; modern works of forensics, gynecology, and midwifery; Indian activists on the child marriage question; and medical statistics on childbirth and mortality – to declare that the age of consent ought to be raised from 10 to “14 at least” with the age of marriage set at 16 years. As Sen argued, even twenty years before, during the debates over the Brahmo Marriage Act in 1872, medical opinion on the age of marriage had, in fact, converged around a much higher age (see Figure 1.1). “I would have gone for a higher age than 16,” Sen clarified, “had I not been hampered by the knowledge that that is the law of England.” (Sen was mistaken on this detail; the minimum age of marriage in England was twelve. He was likely confused because the age of consent had indeed been raised to sixteen by the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885.) He politely registered his opposition to Dr. McLeod, suggesting McLeod had settled on twelve “purely out of deference for Indian public opinion and not from conviction.” Suggesting that the colonial doctor was understandably reticent about interfering in an alien culture, Sen called on his Indian friends to “throw aside for a time all preconceived ideas imbibed on the subject of early association, love for our time-honoured customs, and veneration for the ancient lawgiver, and fix an age that shall stand the test of time founded on the rock of scientific truth, unswayed by motives of expediency or compromise, and undismayed by fear of offending.”Footnote 35 He was not alone in pushing for a social reform resting on “the rock of scientific truth.” In a series of presentations to the Calcutta Medical Society, other doctors emphasized that the medical definition of puberty had undergone a revolution and the age of twelve could no longer be said to correspond to the attainment of puberty.

Figure 1.1 Boyle Chunder Sen’s presentation included “a table showing the age [of marriage] which eminent medical men, European and Indian, thought most conducive to the well-being of the Indian community [in 1872].”

Surgeon Major B. L. Gupta, a civil surgeon at Hooghly, insisted that over 61 percent of Indian girls commenced puberty well after the age of twelve, and the age of sixteen would make for a more suitable age of marriage and consummation, explaining:

When we study the anatomy and physiology of the female generative organs, we find that to a certain age they remain small, rudimentary and functionally inactive. After this age the organs become larger, more developed in structure, and functionally active. The ovaries begin to discharge ovules or female generative elements which remain ready in the female genital tract for impregnation by the male generative elements. When this has taken place, a girl is said to have arrived at puberty, indicated in the large majority of cases by the appearance of menstruation and accompanied by certain well-marked changes in the female system. For instance, “the pubes become covered with hair, the breasts enlarge, the pelvis assumes its fully developed form, and the general contour of the body fills out.” These changes signify that the female is capable of conception and child-bearing. With all these forward changes and sexual capability in a girl, we find that, even on the establishment of puberty, her system in general, and generative organs in particular, are far from being mature, and that it will take at least three to four years for a girl to attain that maturity.Footnote 36

Surgeon Major Gupta thus enumerated the anatomical signs of puberty while questioning whether the early indicators could be taken as a sign of maturity in a general sense. Elaborating on the question of “general maturity,” Dr. MacLeod clarified that the medical opinion on the relationship between menstruation, puberty, and maturity had undergone a revolution, with the consensus being that the “general maturity of the body – full development and growth, adult nervous and mental capacity and power are [sic] not reached for many years after puberty.”Footnote 37 Ultimately, the Calcutta Medical Society unanimously adopted a motion put forward by Major E. A. Birch (Principal, Calcutta Medical College) proclaiming that the appearance of first menstruation was no indication of the “full development of the organs of generation”; that early consummation was unphysiological and “injurious to the welfare of the mother, and offspring and therefore of the race”; and that “a girl is not competent physically or mentally to give her consent to sexual intercourse until she has completed 14 years of age.”Footnote 38 In other words, there was no medical consensus for the selection of the age of twelve as the age of consent on the grounds that it signified the onset of puberty, or that it captured some key transformation in the physical capacity to have sex and reproduce. Why, then, did Scoble insist that the age of twelve was nothing but the age of puberty?

From the very start, Scoble had tried to present his amendment to the age of consent as a restoration of – and therefore not an interference with – Hindu and Muslim injunctions regarding the age of puberty. While Hindu authorities enjoined that a female was to be given in marriage before she attained puberty, as Scoble conceded, they also denounced “in the strongest terms, and award[ed] the most terrible punishments, both here and hereafter, to the sin of connection with an immature girl.”Footnote 39 Muhammadan law considered puberty and discretion the essential conditions for the capacity to enter marriage, and thus clearly proscribed prepubertal consummation. In his reading, “both the great divisions of the population of India” therefore concurred that puberty signified a readiness for marriage, which put both traditions in happy coincidence with the biomedical common sense that Scoble illustrated by (selectively) quoting Dr. McLeod:

Female children under the age of puberty are physically unfit for sexual intercourse, and such intercourse with sexually immature female children, under any circumstances, should be declared an offence punishable by the law.Footnote 40

While acknowledging that the age of twelve was not high enough to protect all prepubertal girls, Scoble insisted that his proposed amendment would “cover 39 per cent of the girls of India.”Footnote 41

Historians have read Scoble’s bill – and his selection of the age of twelve – as a concession to Hindu sensibilities, and therefore as a political compromise between the Hindu orthodoxy and the colonial state, and a reconciliation of native and colonial masculinities.Footnote 42 But it is equally important to recognize that Scoble quite deliberately presented the age of consent as an epistemic compromise, by insisting that the age of twelve was a mere translation of the “age of puberty” that was so significant to the understanding of ritual personhood and legal capacity among Hindus and Muslims alike. But this rough translation of a fact about the body (puberty) into a specific number (the age of twelve) could not be easily effected, as evident from the two discrete sets of concerns that were raised. Medical experts were wondering what the grounds were for translating the age of puberty as the age of twelve: Why not the age of thirteen – or even sixteen? Religious commentators were asking similar questions, but with a distinct inflection: What were the grounds for substituting the “age of twelve” for the “age of puberty”? Why not let the “age of puberty” stand as a referent on its own? As we will see, it was not simply a matter of one group pushing for a higher age of consent and the other for a lower one, for the two sets of objections had distinct bases: while one group contested a particular age of consent, the other questioned whether chronological age as such could be used to dictate normative conduct for the Hindu female.

For Muslims, it is important to recall, Hanafi law provided a minimum chronological age limit for puberty at twelve years of age for boys and nine years for girls, and in the absence of direct evidence, assumed that persons of either sex attained puberty at fifteen. In Shi’a law, males were presumed to attain puberty at fifteen and females at the age of nine years, unless there was individual evidence to contradict these assumptions. However, these were but rough translations to aid the administration of Islamic juridical principles; the “age of puberty” originated from a distinct epistemological and ethical order.Footnote 43 It depended on the individual’s development and declaration, which could not be reduced to a numerical average applicable to all. After taking the pulse of Muslims in Bengal, the region where the agitation among Hindus was the highest, the Honorable Nawab Ahsan-Ullah assured the Legislative Assembly that his inquiries in Dacca and Calcutta revealed that “the greater proportion of Muhammadans in Eastern Bengal will regard it [the 1891 Bill] favourably,” since Islam forbade cohabitation before the age of puberty, and this “age may generally be taken to be eleven or twelve.” Even though, as Moulvi Abdul Jabbar from Calcutta pointed out, the minimum possible “age of puberty” was considered to be nine years by Mohammedan law, there was unlikely to be an objection to Scoble’s bill, as it upheld the principle of the age of puberty while demonstrating that “twelve” could be read as a chronological approximation of that physical condition.Footnote 44 Khan Bahadur Muhammad Ali Khan assuaged the government’s fears on a possible Muslim protest against the bill by explaining, “[A]ccording to our religious books the minimum age at which a girl is supposed to attain puberty is nine years, but the maximum limit is fifteen years.” Given there was no hard-and-fast chronological age attached to “puberty,” and since “girls seldom attained puberty before the age of twelve or thirteen,” he felt the proposed law would provoke no opposition as it posed no threat to religion.Footnote 45 The most vociferous of the Hindu protestors were not, however, convinced by Scoble’s rough translation of a significant bodily event (the onset of menstruation) to a number (the age of twelve).

The Hindu orthodoxy insisted that “puberty” could not simply be represented in terms of chronological age; such a rough translation of an embodied fact into a numerical convention neither took into account individual development nor the ritual significance that attached to menstruation. Besides, it ignored the Hindu injunction that girls be married off before the onset of menstruation. The sharpest critique came from the prolific Mr. A. Sankariah, president founder of the Hindu Sabha, Trichoor, who sent in several letters to clarify why the two measures of personhood – chronological age and the age of puberty – were irreconcilable. He explained the Hindu shastric view by which vivaha (marriage) was considered a life-cycle rite (samskara). The rite of giving a kanya (virgin) to a male was a crucial obligation of the father, and the reception of the kanya marked the husband’s assumption of duties as a grihastha or householder, which was the second and (according to the lawgiver Manu) the most important of the four ashramas by which the different periods of Hindu life were distinguished. Without a wife a Hindu householder could not perform his requisite duties (e.g., producing male offspring, attending to his ancestors, worshipping the gods). For a Hindu female, marriage was the only rite allowed, and she could only partake in these rituals – and in that sense, only became a person – with marriage. Moreover, as Sankariah explained in one of his many letters to the Legislative Department, the new stipulation on age would also interfere with the performance of the rite of garbhadhan, which he translated into a medicalized idiom as the “rite of conception or the sacrament of impregnation,” that was to be performed right after the onset of the first menstruation.Footnote 46 According to the Manusmriti, he explained, a husband was obliged to approach a wife “between the fourth and sixteenth days after her first monthly course” for the performance of the garbhadhan, a ceremony comprising certain chants and ceremonies as an invocation to the gods to prepare the womb for the conception of healthy offspring. With its nonperformance the womb itself became polluted so that future sons born of the womb could not offer pinda or ritual offerings to ancestral spirits. The father who neglected to arrange for its performance incurred the sin of feticide, while a wife deprived of it was fated to be a widow in many successive lives. To Sankariah, the concerns expressed by the social reformer were irrelevant and extraneous to the Hindu understanding of the person; to him, “what Europeans call child marriage is the Hindu baptismal sacrament for girls to be trained in the general rules of caste, comprising ablutions, prayers, fasts, pollution, etc. There are also particular religious duties to seek the blessings of the Rishis, Devas and Pitris, unknown to modern science, but who are the Governors, Teachers and Saviours of the Hindus.”Footnote 47 “A child who can be taught at school is quite aged enough to learn these particular and general duties,” he continued, repeating a familiar refrain of the time that “the worldly notion of physical consummation is altogether absent in child marriages.”

An understanding of the person that posited a ritual significance to menstruation and saw marriage as a life-cycle rite fundamental to the continuation of an entire web of familial relations and affecting even the afterlives of intimate kin thus clashed with another tradition in which menstruation signified biological capacity and marriage was contingent on personal consent. While Scoble upheld an idea of personhood locatable in the secular or anatomical body that aged with time and was legible to medicolegal experts, Sankariah was concerned with a notion of the person that was presided over not by doctors but by “Rishis, Devas and Pitris, unknown to modern science.” Sankariah upheld the most extreme version of this understanding: for him, a female’s personhood was so wholly reliant on her marital status that he felt “it was a thousand times better for one out of a ten thousand girls to suffer from the hasty indiscretion of a husband, than for several girls to be defiled and outcasted by an invasion of their persons by strangers.”Footnote 48

The more moderate dissenters steered clear of this violent conclusion, but several of them referenced the Hindu understanding of personhood to critique the privileging of chronological age by Scoble’s bill. Taking at face value Scoble’s claims that his proposed age of consent was consistent with Hindu and Muslim understandings of marriage, since the age of twelve was merely a convenient shorthand for the bodily changes that had ritual significance for Hindus, they wondered why the law could not then simply mandate that the age of puberty, in each individual case, was the age of consent. Taking this tack, Romesh Chunder Mitter, an erstwhile Justice of the Calcutta High Court and a nominated native member of the Imperial Legislative Council, submitted a minority report against the selection of the age of twelve as the age of consent. Claiming that he personally believed that the ages of fifteen or sixteen were better suited as the minimum age of marriage on physiological grounds, he nonetheless insisted that puberty – “a certain point of development of a human being” – constituted a better test of nubility, and there was “no such unmistakable age-criterion of maturity.”Footnote 49 Rhetorically conceding Scoble’s claim that there were few disagreements in the intent of the Shastras and the Age of Consent Bill, he pointed out that the shastric injunctions that privileged “a certain physical condition” over chronological age were sounder not only on religious grounds but also on biomedical and legal grounds. If puberty was to be instituted as the effective age of consent, girls older than twelve could also benefit from protection. Mitter thus broke down Scoble’s two-step contention – that for both “great divisions of the Indian population,” the “age of puberty” referred to the appearance of the menses, and that the age of twelve was the average age at which that condition occurred – to argue that the law would be more effective if the age of consent were to be raised to thirteen, and an exception made for each case when the menstruation appeared at an earlier age. Preempting the counterargument that the fact of puberty could not be established in courtrooms, Mitter insisted that menstruation “admits of more satisfactory proof than age in this country,” especially as its onset was often “followed by certain religious rites which will afford the required evidence in a judicial investigation.”Footnote 50 Mitter was not alone in making this suggestion.

Rai Bahadur V. Krishnamachari insisted that Scoble’s bill was flawed and could never attain its stated object – the prevention of “pre-menstrual congress” – in the case of “the poor girls who have not attained puberty, though they have completed that age.”Footnote 51 He further pointed out that the age of 12 was a particularly “dubious age to fix by law,” for “unlike the limit of 10 years in the existing penal law when a girl looks a mere child, or of 14 years when puberty will have been reached and evidence of maturity will be visible,” 12 was just the age when a malicious complainant could raise questions about a girl’s age to harass innocent families. He proclaimed fourteen as the “most approximate age of puberty in this country involving little inquisitorial inquiry and less chance of a doubt at first look” and recommended a “saving clause” for wives in cases where a wife attained puberty before that age. While observing that a more systematic registration of births would help make age-based stipulations more practical to enforce in the future, he proposed a bold alternative – that “the date of arrival of a girl to womanhood, which is regarded by Hindus as a girl’s second birth and which they celebrate as a festive occasion,” be entered into the official record. While the last suggestion made sense in a context where colonial officials conceded it would be “impossible to compel such documentary proof of birth as in the West would be insisted upon,”Footnote 52 it was most certainly ignored. It is worth pondering why it would not have made sense to have one of the key indicators of “puberty” recorded by the state, given Scoble’s insistence that his intention was to prevent prepubertal consummation. In their minutes to the Bengal government, two justices of the Calcutta High Court argued that while in theory “age limit is more definite and easily ascertainable than the attaining of puberty,” the situation was quite different in India.Footnote 53 Some felt that it would be “impossible to compel such documentary proof of birth as in the West could be insisted upon.”Footnote 54 Diwan Narindra Nath, assistant commissioner of Multan, prophesied that “much difficulty will arise in the determination of age” and pointed out that “medical science does not help much in determining with precision the age of a girl between 11½, 12½ or 13.”Footnote 55 Another respondent, who wholeheartedly supported the government’s right to intervene into private life, nonetheless remained skeptical regarding medical proofs of age:

It is impossible for medical science, in its present state, to exactly determine age. Its evidences based on teeth, the height and weight, the progress of ossification and the growth of hair, will prove utterly useless when it will be asserted by the indicted husband that his wife was 12 years and 2 days old the day he had sexual intercourse with her.Footnote 56

He proposed, instead, that “menstruation, the development of breasts, the growth of hair on the private parts should be declared irrebuttable presumptions of an age exceeding the interdicted one,” thus taking Scoble’s claims on the embodiment of “the age of twelve” to its logical conclusions while insisting that the evidence of the body ought to trump the fact of chronological age in each individual case.Footnote 57

That these suggestions to record the arrival of puberty rather than the date of birth barely received discussion is evidence of the ways in which colonial and national states “manage their own denizens through an official time line, effectively shaping the contours of a meaningful life by registering some events like births, marriages, and deaths, and refusing to record others.”Footnote 58 While Scoble paid lip service to the importance of puberty among “the two great divisions in the population,” the rites of puberty were neither relevant to the notions of personhood upheld by the colonial state nor crucial to upholding its rule of law. A member of the governor general’s council, Honorable G. H. P. Evans, remarked that while he “should have been very glad if possible to meet the religious scruple, fanciful as it appears,” such a concession was “absolutely impracticable, and the reasons why it is impracticable are perfectly clear.”Footnote 59 To Evans, objections based on the frailty of the proofs of age were superfluous: “There is no doubt difficulty in many cases in ascertaining age,” he conceded, “just as there is great difficulty in this country in ascertaining any other fact by oral evidence,” but nevertheless “our law bristles with instances of limits of age,” such as the age of majority and the age of criminal responsibility. He rejected the possibility that the arrival of puberty as such could be recorded by the state, pointing out that the festivities and ceremonies celebrating the appearance of the menses could not be trusted as evidence of a biomedical fact.

Even though Scoble presented the “age of twelve” as a compromise between liberal legal understandings of personhood and Hindu and Muslim law on capacity by insisting that it was a mere translation of the stipulations on puberty contained therein, he upheld chronological age as the natural and universal, and thus the only appropriate and practical, measure of legal personhood. In other words, the Age of Consent Act buttressed liberal legal understandings of the person that relied on the secular, anatomical body as its site. The selection of chronological age over the corporeal signs of puberty was intended to leave behind the messiness created by individual differences that would undermine the practical and uniform application of the law. It was also intended to leave behind the uncomfortably gendered understanding of personhood in Hindu law, wherein the body was a site of ritual signification. Paradoxically, however, as we see in the next section, while age stipulations in the law had long existed as a convention detached from the messiness of corporeal difference, it was during the age of consent debates – and because of the insistence that the age of twelve corresponded to the age of puberty – that age came to be defended as a fact that attached to the body. Moreover, no less than its Hindu counterpart, the liberal legal understanding of the age of consent was itself thoroughly and invariably gendered.

1.2 Age Without the Body: The Majority Act and the Child at Labor

The laws of all nations are agreed in recognizing the fact that immaturity constitutes to a greater or less extent a personal incapacity to do a legally binding act, and to be personally responsible for one’s action. But the age or ages at which such incapacity or irresponsibility shall cease is purely artificial, and even amongst races exposed to similar physical conditions greatly varies.Footnote 60

The age of consent debates of 1891 marked a shift in colonial law whereby age, hitherto viewed as a proxy for certain physical and mental developments signifying legal capacity, came to be naturalized as capturing the “truth” of biological maturity. The stringent demands for proofs of age in cases involving the age of consent and marriage in the decades that followed capture this phenomenon, whereby the proxy became significant in itself. This naturalization of a convention – age – was by no means inevitable, as can be clarified by examining the discussions around the Majority Act of 1875. In introducing the bill stipulating a uniform age of majority as “eighteen years of age” for all persons domiciled in India, the Maharaja of Vizianagaram conceded that the age of majority was merely a convention, or a proxy for capacity. Before the bill was passed into law, the age of majority for natives of India had varied according to race and religion (and implicitly, by gender).Footnote 61 Hindus of the Bengal school attained majority at the close of the fifteenth year, while those of the Mithila and Benares Schools did so at the end of their sixteenth year.Footnote 62 Muslims attained majority at fifteen (by some authorities at fourteen), unless they had already arrived at puberty previously. In short, the priority to be accorded to biological and chronological age remained fluid. As per the Succession Act of 1865, Hindu or Muslim placed under the tutelage of the Court of Wards had “his nonage prolonged until he completes his eighteenth year.” European British subjects who were neither Hindu nor Muslim and domiciled in India acquired majority at the end of their twenty-first year. The lack of uniformity not only meant that individuals with the same age but belonging to different communities had distinct legal statuses but also meant that the same person could reach majority for some purposes but not for others at a given age. The confusion multiplied in public contracts: if the Muslim man at eighteen entered into a contract with a European British subject two years older than himself, the contract could be invalid since the latter was still a minor.

The Majority Act was driven by a quest for uniformity, especially in the case of such cross-cultural commercial contracts. But much as it would in 1891, the choice of the particular chronological age to indicate majority for all communities and races had proved sticky. What would be the criteria for determining legal capacity: biological maturity or mental capacity? Could the signs of maturity recognized by Hindu or Muslim law – the onset or completion of puberty in each individual case – be translated into chronological age? As respondents pointed out during the debates over the Majority Act, the idea of minority originated in considerations of intellectual deficiency, and would therefore naturally “vary according to the physical and mental constitution as well as habits of life of the people inhabiting each country.”Footnote 63 Was a uniform age of majority even possible or desirable? The Maharaja of Vizianagaram, who introduced the bill in the Legislative Assembly, had clarified that while the laws of all nations linked maturity to legal capacity, “the age or ages at which such incapacity or irresponsibility shall cease is purely artificial, and even amongst races exposed to similar physical conditions greatly varies.” Hence, as he went on to note, the age of majority was twenty in France, twenty-one in England, and twenty-five in Denmark.Footnote 64 Disparity between various nations was not an issue as long as there was clarity on the age of majority – designated with reference to chronological age – for each nation.

And since it was an artificial distinction, “it is in no way regarded as a matter of religious sentiment by any sects or individuals of the creed to which I belong,”Footnote 65 the Raja assured official members concerned that the new age of majority might interfere with alternatives that had “quasi-religious sanction.”Footnote 66 With some deft translation, the Raja suggested there was an implicit approval for a higher age of majority in Manu, whom he described as “the greatest authority in the Hindu religion, whose institutes are highly approved of – nay, even venerated in the western world.”Footnote 67 Manu’s well-known injunctions that the first quarter of a man’s life be devoted to the accomplishment of studentship, and the second to married life, were premised on the belief that “a man’s age is 100 years,” but “even taking the present average of human life it may be fairly said to be 75, and a quarter of that is a few months more than 18.”Footnote 68 He concluded that fixing the age of majority between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five would therefore be in keeping with Hindu sentiment. He pronounced the selection of sixteen as the age of majority during the colonial codification of Hindu law as a misinterpretation, or an error introduced by pundits: citing the Narada Smriti the pundits had asserted that a male attained majority at sixteen, and “if he has no parents, becomes independent,” but the same text also conceded that such a boy, if incompetent, must not be recognized as a major and could not make demands for his property even at the age of sixteen. Likewise, the Raja argued, Muslim justices had confirmed that the prescribed age of majority referred only to the “right for practicing offices connected with religion.” A uniform age of majority for the “exercise of civil rights and privileges” would not interfere with religion.Footnote 69 The insistence that the status of majority (relevant with regard to economic transactions) was distinct from the status of full personhood (signifying the capacity for religious obligations) reflected the founding fiction of colonial law, namely, the bifurcation of the civil law into religious and secular matters.

This bifurcation had been introduced in 1772, with Warren Hastings’ Plan for the Administration of Justice. In this well-known plan to establish a system of civil law, a cleavage was introduced between matters deemed to be of a religious nature and those perceived as secular. In the first case, Indians were to be governed by religious law, to be termed their “personal law” inasmuch as it was inherent to the person, regardless of domicile, while British principles were to form the basis of other matters of law, including procedural and adjectival law.Footnote 70 The Raja’s insistence that the age of majority did not interfere in religious matters was a fantasy generated by a schematic bifurcation based on the premise that “religions constituted discrete entities and systemic structures of law and belief that directly governed people’s everyday practice; that these religious laws primarily centered on the family … so that territorial laws grounded in British legal principles could be applied in other matters of civil law without significant violation of the core of religious law.”Footnote 71 The system of personal law also defined natives of India as belonging to two distinct categories, Hindu and Muslim, for Hastings had famously proclaimed, “In all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages, or institutions, the laws of the Koran with respect to the Mahomedans, and those of the Shaster with respect to Gentoos [Hindus], shall be invariably adhered to.”Footnote 72 As the vast scholarship on colonial law amply demonstrates, this policy of nonintervention constituted, in fact, a fundamental break from Hindu and Muslim jurisprudence, not least in the comprehension and definition of “religion” and “law,” as well as “community” and “family.” As the colonial state defined, codified and adjudicated religious law in consultation with their native consultants, and translated concepts from one system to the other, religious precepts and colonial legal procedures became entwined just as they were purportedly being separated. Unpicking this terrain, historians of personal law have shown how principles of a liberal theory of property were entrenched in the system of personal law and how the nature of individual ownership, the power to alienate property, and the nature of liability for contracts were the dominant terms of reference within a system of personal law, such that the Indian “family” itself came to be understood primarily as an economic unit.Footnote 73 The separation of family and religious status, on the one hand, and the economy and secular status, on the other, was preserved, at least on paper, during the passage of the Majority Act.

While certain respondents remained skeptical that the question of majority could indeed be delinked from religion in a context where the system of early marriages prevailed, where “great importance was attached to the ceremonies for attaining puberty, majority and marriage,” and where “all marriages are arranged by families,”Footnote 74 the Majority Act explicitly stated that all matters “relating to marriage, divorce, dower, and adoption” would be left untouched with respect to the personal laws of Hindus and Muslims.Footnote 75 As age was explicitly acknowledged as a mere convention, detached from the body, the subject of the Majority Act – or the legal person with regard to matters of property and contracts – was not explicitly gendered. The presumption that the subject of the law was male, however, was so entrenched that the advocate general of Madras, H. S. Cunningham, felt it necessary to propose that it be made explicit that the Act extended to females. This was not done, and the law simply stated, “[E]very person domiciled in British India shall be deemed to have attained his majority when he shall have completed the age of eighteen years and not before.”Footnote 76 The female body was, in common perception, left untouched by the Majority Act. It was also assumed that the very body of religious law – gendered female in the colonial and national imagination – had been left alone.

A gendering of the law itself is also evident in debates in 1891 surrounding the child in labor, as opposed to the child in marriage. In his closing statement on the Age of Consent Bill, Scoble had urged that “the British law would fail to provide adequately for the safety of the children of this country if, while it protects them from all other kinds of ill-usage, it failed to protect them from a particular form of ill-usage infinitely more revolting, and infinitely more disastrous in its direct, as well as in its remoter, results, than any other form of ill-treatment to which they are liable.”Footnote 77 Of these other forms of “ill-usage,” child labor was likely at the top of his mind, for, directly after his motion to amend the age of consent was put and agreed to, on March 19, 1891, Scoble that very day went on to ask the Legislative Assembly to consider a bill to amend the Factories Act of 1881. The bill, originally introduced in January the previous year, included among its provisions a proposal to raise the minimum age of children employed in factories from seven to nine years of age.Footnote 78 While Scoble had evoked universal humanitarian standards of child protection to ask for a change to the age of consent, he readily conceded the difference of the Indian child at labor. Indeed, he insisted that even though Britain had signed the provisions of the recently concluded Berlin Labor Conference restricting the employment of children below twelve years of age, in India, “the age of nine is a reasonable equivalent.”Footnote 79

In the decades before, the interest in the regulation of factory labor had emanated primarily from the metropole, and even when child protection was used as a rhetorical tool to push for changes to the labor law, it was barely disguised that the real concern lay in lessening the competitive advantage to Indian mill and factory owners with easy access to exploitable labor.Footnote 80 When the Manchester Chamber of Commerce passed a resolution to extend the provisions of the British Factory Act to the textile factories of India in 1888 – complaining of the unfair advantage provided to Indian factories because of the lack of regulation of labor – the Madras Chamber of Commerce had retorted that any “such legislation should be guided, not by the desire to procure uniformity with similar legislation in India, so much as by an enlightened perception of what is conducive to the welfare of the country irrespective of competing interests.”Footnote 81 Likewise, in response to the Blackburn and District Chamber of Commerce’s demands for uniformity in the regulation of child labor, the Indian commission of inquiry into the conditions of factory labor had pointed to “the fallacy of comparing the ages of European and Asiatic children, or the work done by Indians with that exacted in European countries.” These discussions on the minimum age of labor seemed less concerned with the condition of children’s bodies than with that of the infant industry in India.Footnote 82

The Indian commission also proclaimed that a minimum age of nine was in compliance with the spirit of the discussions at the Berlin Labour Conference of 1890, which had fixed twelve as the minimum age with a proviso for reduction to ten in southern countries, for “an Indian child of 9 is at least as precocious as an Italian child at 10,” just as “there can be little doubt that a Native of India at 12 is at least as fully developed as a child of Northern Latitudes at 14.” The evidence? Observers had been “greatly struck by the bright cheerful look of children employed,” even with the present minimum age of “only 7.” One respondent even insisted his “only doubt has been whether we are not going rather too far in raising it to 9,” especially since “the labour is easy and does not impose anything like as great a strain as that of ordinary school life.” During these discussions, for each argument made that “there should not be one law for England and another for India,” the Indian Factories Act was defended on the grounds that such equivalence could only hold good with regard to the general principle underlying legislation that had to remain specific to each location: “Life and limb shall be protected and the health of all women, young persons and children, as far as possible, with reference to the conditions of the country, assured.”Footnote 83 The contrast between the rhetorical moves made with regard to child marriage and child labor suggests that the imagery of sexual abuse had a power to generate passions that were scarcely matched by other forms of ill-use: some members of the Legislative Assembly even pointed out, without irony, that most “young persons” of fourteen and sixteen were married in India, and many were fathers, and therefore putting restrictions on their labor was out of touch with the Indian reality. That these young persons were presumed to be male may be surmised from the fact that the contemporaneous discussions on the age of marriage were barely referenced.

The Majority Act (1875) and the amendment to the Factories Act (1891) contained prescriptions regarding age, but these were premised neither on the scrutiny of the body nor on the naturalness of age. These age stipulations – acknowledged to be purely artificial – were also presumed to have left religious sensibilities untouched. While technically located in the domain of criminal law, the “age of consent” straddled the historical breach between secular and religious law in India in attaching age to the female body. Likewise, age of consent legislation around the world helped naturalize age as a measure of all humans, by indexing it to changes in the female body. While feminist critics have revealed to us law’s gender – or the ways in which legal concepts are gendered – they have stopped short of noticing how law’s temporality – its organization of time into the past, present, and future – was made flesh in the grounding of age in the female body. Indeed, as we see in the next section, law’s temporality, as captured in the placement of consent along a temporal scale and as naturalized in the child-adult distinction, has remained intractable in much of the feminist scholarship on the Age of Consent Act of 1891. In upholding law’s temporality, this scholarship reproduces the child as autoptic – visible in the body and self-evident to all. To undo the assumption that age is a natural measure of humans, and hence a universal guarantor of consent and access to rights, we need to recognize the provincial, liberal, and juridical roots of the epistemic contract on age.

1.3 Consent and the Epistemic Contract on Age

In India, as around the world, age of consent legislation has proved a fertile ground not only for the study of gender relations and sexual norms but also for querying the very meaning of political concepts such as sovereignty and citizenship. In her work on age of consent laws across the British Empire, Philippa Levine suggests that age of consent laws, couched in the language of protectionism aimed only at women, “established political gender boundaries delimiting female rationality” and marking men as natural citizens of the world.Footnote 84 Approaching the gendered logic of consent another way, the political theorist Carole Pateman interrogates the fetishization of “consent” in liberal political theory, arguing that a sexual contract that organizes men’s exploitative access to women’s sexuality and labor precedes a social contract and upholds it, guaranteeing the subjection of women to men.Footnote 85 Wendy Brown goes further, suggesting that in contemporary societies, the legacy of gender subordination is not simply found in contract relations as such but “in the terms of liberal discourse that configure and organize liberal jurisprudence, public policy, and popular consciousness.”Footnote 86 While the semantics of consent has thus been extensively debated, this section queries the use of age as its measure. It revisits the extant feminist scholarship on the age of consent in India to suggest that its reliance on the law’s temporality – or the law’s organization of time as past, present and future as a way to manage access to rights and privileges – makes it yet another technology for the production of the autoptic child. Reading sideways, we see how in feminist scholarship on the age of consent, the “child” is made the paradigmatic natural against which the historicity of the “woman” can be ascertained.Footnote 87

In an excellent example of this scholarship, and in her pathbreaking work on the emergence of women as the subject of rights in India, the historian Tanika Sarkar focuses on three key moments in the nineteenth century: the abolition of sati in 1829, the legalization of remarriage for Hindu widows in 1856, and the raising of the age of consent within and outside marriage in 1891. These moments in straight time serve, for her, as examples of the “piecemeal processes” that coalesced in “a fledgling notion of something like rights – translated as a few immunities from sexual, physical or intellectual death,” which “emerged as political values in the sphere of women’s lives even before they [were] articulated in the public and political realms.”Footnote 88 In Sarkar’s reading, these moments in India’s legal history cumulatively served to erode the claims of family, kin, and community over Indian women, and to peel norms away from custom and scripture. In a later piece on the Age of Consent Act, Sarkar analyzes how “the fledgling notion of a title to life was expressed in the word ‘consent’: a polyvalent, mid-term word, containing the seeds of concepts about personhood and rights.”Footnote 89 This feminist analysis, grounded in the juridical idiom of rights, and considering modern law as the chief site for the emergence of women as subjects, is entirely embedded in the law’s temporality.

Such a reading that subscribes to the law’s organization of time invariably naturalizes the child. Evoking the child as a natural object, an object without history, Sarkar urges that in order to understand the emergence of woman’s rights in India, we must “start with a little girl’s death and the multiple representations of this event.”Footnote 90 The “little girl” she writes of is, of course, Phulmoni, whose brutalized body, in her reading, “shocked the complacent male gaze” that had hitherto seen the child wife as a “delightful little doll.” The signs of violence on the “broken young female body” generated new and anxious questions for reformers: “Were they talking of the woman or about a mere child yoked to untimely marriage? Was there a separate stage in the woman’s life as childhood, and if so, was it compatible with marriage?”Footnote 91 While noting the halting questions on the status of the young wife that were voiced at the time, the historian stops short of pursuing these questions. The historian elides the child not by ignoring it but by taking it for granted; the child serves as the naturalized foil in the history of women.

Let us pause to reflect on how naturalization – both of the child and of law’s temporality – creeps into this (liberal) feminist account of Phulmoni’s case. The account stops short of recognizing the juridical construction of the child, while even a straightforward historicist reading would reveal that not only was the dead wife not a child by the standard enshrined in the colonial law at the time but even the mother who doubtless thought of the dead girl as her own child did not demand justice by taking this relational understanding to make an argument for child protection. Sarkar’s reading of Phulmoni’s case is an instance “where the historian’s propriety of response is expressed through a kindness to long-dead children, and a dramatic rehearsal of horror at conditions they might have experienced.”Footnote 92 Such a reading takes present-day juridical-sexual norms as the basis of analysis, as is apparent when Sarkar faults the colonial judge for criticizing neither Phulmoni’s brutal husband’s “nature (which inclined him to enjoy a child), nor the domestic-conjugal custom that allowed him to do so.”Footnote 93 In reading Phulmoni’s husband as a pedophile, Sarkar renders Phulmoni as autoptic, an object without history.Footnote 94

Is the autoptic child inevitable, and even necessary, given Sarkar’s commitment to the idiom of rights and consent? Sarkar rejects both the postcolonial contention that the very notion of rights has a European genealogy and the postmodern feminist critique that sees the liberal commitment to consent as both obscuring and upholding gender difference. She argues that liberal norms – criticized in other contexts – were especially meaningful to gender justice in India, inasmuch as even the hint of these concepts granted a personhood for the woman denied her in Hindu law. She finds postcolonial and postmodern critiques of rights discourse particularly dangerous inasmuch as such critiques serve to vest opponents of liberalism, including the Hindu right, with a rebellious and emancipatory agenda – a phenomenon that must be guarded against given the spectacular rise of Hindu nationalism in India.Footnote 95 Nuancing Sarkar’s analysis of the contingent and piecemeal processes by which the notion of women’s rights took root in India, Mrinalini Sinha nonetheless finds in women’s associational politics in the interwar years evidence of the development of an “agonistic or truly adversarial liberalism: a language of rights that developed both alongside and against classical European liberalism.”Footnote 96 Likewise, in her account of the relationship between legislative social reform discourse and the accretion of the rights of women in India, the legal historian Rachel Sturman reads the Age of Consent Act as doing the work of humanization in the arena of Hindu law, as women came to be distinguished from property and were accorded “new human value, grounded in the secularization and universalization of the female body.”Footnote 97 This privileging of rights as the object of analysis, even when understood in a historically specific way as contingent and translated, is necessarily embedded in the temporality of the law.

Even the scholarship that has variously pointed to the emptiness of the notion of consent remains committed to law’s temporality. In an early reflection on the question, Himani Bannerji demonstrates how consent was given a “purely physical meaning” – as the ability to undergo penetration – during the age of consent debates in 1891 and argues that “consent” pertained not to the woman’s wishes but to a legal guardian’s right to alienate a woman’s body to a male user as husband or client.Footnote 98 Likewise pointing to the limits of consent, Ashwini Tambe suggests that the age of consent defined new boundaries of girlhood in ways that denied sexual agency to young women and extended patriarchal and familial control over their bodies through state control.Footnote 99 In distinguishing between true and false consent, and full and partial consent, or in critiquing the paradoxical entailments of the very notion, these works stop short of querying the law’s temporality and the placement of agency along a temporal scale. To borrow from Steven Angelides on a queer theory of age stratification, when “feminist assumptions join forces with the conventional liberal state position in what has become the hegemonic cultural perspective, in which children are incapable of informed consent to sex until certain arbitrarily set ages,” the child is rendered autoptic.Footnote 100 A queer theory of age stratification, as Angelides explains,

would insist not on upholding arbitrary distinctions between linear and chronological stages of individual development but on subjecting these distinctions, and the sociopolitical, legal, and institutional formations that are both their cause and their effect to much-needed critical scrutiny. This scrutiny would entail a thorough reexamination of concepts such as knowledge, consent, and power as they have been articulated through the linear and sequential logic of age stratification. How, for instance, does the social axis of age inform our understanding of power and knowledge relations? How are age-stratified notions of subjectivity constituted through the power-knowledge nexus? What is the relationship between consent, power, and age-stratified concepts of subject formation?”Footnote 101

But instead of merely conceding the arbitrariness of the specific chronological ages to which legal capacity to consent is attached, as Angelides does, we can – and must – go further still, to question the conceit that age as such is the measure of legal capacity. In failing to do so, we as feminist historians replicate the liberal state’s placement of agency and capacity along a temporal scale and obscure alternative ways of recognizing personhood and imagining justice.

The notion of consent, of rights, of legal personhood that is now commonplace to us is caught up in law’s temporality that organizes an individual life into discrete units of time measurable by chronological age, and which is paradigmatically expressed as the child-adult distinction. In acknowledging this my intent is not simply to critique (once again) the discourse of consent or rights, whether for its European genealogy or for the emptiness of its promise, but simply to point out that the feminist commitment to consent and rights, both as an object of scholarly analysis and an end point of political activism, is contingent on an acceptance of law’s temporality. The naturalization of the child goes hand in hand with the temporalization of agency that remains at the heart of both liberal jurisprudence and liberal feminist (and ultimately, even queer) analysis. The rootedness of age in liberal jurisprudence is overlooked in recent works that are otherwise exemplary in drawing attention to the historicity of age. For instance, in an excellent recent volume on age in America, the editors write, “[A]ge is both a biological reality and a social construction,” suggesting that while age intersects with other ascriptive traits such as gender and race, it is nonetheless distinct from these categories as we will all pass through different chronological ages if we live long enough. They suggest that unlike gender and race, age captures something of the process of “biological development,” even though “the meanings that we assign to precise ages … are cultural constructions.” Minute age distinctions in the law, they argue, are “arbitrary, but necessary.”Footnote 102 In a work remarkable for its attention to the historically contingent construction of age, the biological basis of age is assumed, as is its necessity to the law. Each of these presumptions – (1) that age, unlike say, gender, is biological; (2) that we all pass through the gamut of ages; and (3) that age-based stipulations in the law, while arbitrary, are necessary – come undone in queering (liberal) law’s temporality and by centering colonial contexts.

An investigation of age from India shows in relief that outside of the history of liberal law and its norms of evidence, the meanings attached to specific ages – and to age as such – turn out to be not only arbitrary but also unnecessary. The practice of reading sideways – that is, putting side by side the insights of feminist, postcolonial, and queer theory not only to use these together but also to tease out their respective blind spots – serves us well in this investigation. It helps reveal the particularity of “the law” that has come to stand in for law as such, and which pervades not only our understanding of “biological development” but also our very categories of analysis. As postcolonial critics remind us, and I will let Dipesh Chakrabarty stand as an example here, concepts that are now commonplace to us – including citizenship, human rights, the individual, and social justice – “all bear the burden of European thought and history.” Not only do their roots “go deep into the intellectual and even theological traditions of Europe,” many of them attained their “climactic form in the course of the European Enlightenment and the nineteenth century.”Footnote 103 Even the “human,” so crucial to the social sciences and to our understanding of rights, is forged in European history, and since our conceptions of a socially just future for the human take the idea of single, homogeneous, and secular historical time for granted, one cannot “provide accounts of the modern political subject in India without at the same time radically questioning the nature of historical time.”Footnote 104 To write the history of modern political subjects in India, he suggests, we must reject key “ontological assumptions entailed in secular conceptions of the political and the social,” the first of which is that “the human exists in a frame of a single and secular historical time that envelops other kinds of time.”Footnote 105

Building on Chakrabarty’s insight while reading sideways, we can insist on the centrality of modern discourses of sexuality in enframing the human in this way. For instance, while Chakrabarty finds evidence of “a dramatic example of the nationalist rejection of historicist history” in the extension of universal adult franchise at the moment of independence in India, Chakrabarty stops short of noticing the ontological assumptions entailed in the secular conception of the biological, and thus the historicity and locatedness of assumptions about the nature of human development that undergird “universal adult franchise.” In comprehending age as the intimate expression of secular and uniform time, we can locate the norms of universal adult franchise in secular (European) temporalities and legalities and query its naturalization in the name of biology. Such an understanding of age as a framing of the human in a “single and secular time” reveals how sexual normativity orders and naturalizes the time of history and of the secular human. It is only by recognizing age as an intimate expression of liberal law’s temporality, or as a sexual unit of time, that we can begin to imagine the human outside of “the frame of a single and secular historical time that envelops other kinds of time.”

Here, queer theory is a helpful supplement to postcolonial theory, in reminding us of how sexual normativity organizes and rationalizes the time of capital, or how “concepts such as knowledge, consent, and power … have been articulated through the linear and sequential logic of age stratification.”Footnote 106 But insights such as these are themselves generated from within the (Western) liberal legal universe: while questioning the arbitrariness of certain age limits set in the law, they stop short of noting the provincial origins of age as a measure of the human or of their legal capacity. Age, as I understand it, by contrast, is as an intimate manifestation of the temporality of liberal law, and it is this temporality that underwrites the conception of the modern legal subject – what Samera Esmeir terms the “juridical human” – and thus circumscribes her capacity to consent and gain access to rights. As the law’s temporality – expressed in the form of age stratification – becomes part and parcel of the “contemporary cultural text we inhabit, a discourse whose terms are ‘ordinary’ to a very contemporary ‘us’,” and which both produces and positions “subjects whose production and positioning it disavows through naturalization,”Footnote 107 age-based distinctions begin to appear as a biological given that is crucial to the provision of justice and the attainment of rights.