Introduction

Dementia is a significant concern worldwide with an increasing number of people affected by the disease (World Health Organization, 2012). Over-reliance on specialty care results in increased wait times, which in turn results in delayed and inadequate treatment, management, and overall quality of care (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2010; Aminzadeh, Molnar, Dalziel, & Ayotte, Reference Aminzadeh, Molnar, Dalziel and Ayotte2012; Amjad, Carmichael, Austin, Chang, & Bynum, Reference Amjad, Carmichael, Austin, Chang and Bynum2016). There is a growing consensus among Canadian experts and decision-makers that the focus of dementia care should shift from specialist to primary health care (Moore, Patterson, Lee, Vedel, & Bergman, Reference Moore, Patterson, Lee, Vedel and Bergman2014). Primary health care clinicians are ideally positioned as they usually are the first point of contact and can be as effective as specialists to detect, diagnose, treat, and manage patients and follow-up with their caregivers (Lemire, Reference Lemire2017; Meeuwsen et al., Reference Meeuwsen, Melis, Van Der Aa, Golüke-Willemse, De Leest, Van Raak and Visser2012). However, they are not always well-prepared to do so (Boustani, Sachs, & Callahan, Reference Boustani, Sachs and Callahan2007; Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Dobbs, McKay, Kirwan, Cooper, Marin and Gupta2014).

The World Health Organization and the international InterAcademy Partnership for Health Committee on Dementia have called for national or subnational dementia strategies or Alzheimer plans to better organise care for persons with dementia and their caregivers (Chertkow, Reference Chertkow, Hogan, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Rockwood and Stuchlik2018). Many countries have responded accordingly (Alzheimer’s Disease International Publication Team, 2018), and among these, Canada recently launched its national plan (Government of Canada, 2017). Provincial dementia strategies also exist in Ontario, Nova Scotia, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, and Quebec (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Arcand, Bureau, Chertkow, Ducharme, Joanette and Voyer2009; Government of Alberta & Alberta Health Continuing Care, 2017; Government of British Columbia & Ministry of Health, 2012, 2016; Government of Manitoba, 2014; Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Health and Community Services, & Alzheimer Society of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2004; Government of Nova Scotia & Department of Health and Wellness, 2015; Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, & Ministry of Education [Early Years and Child Care], 2016; Provincial Advisory Committee of Older Persons and the Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan, 2004).

The Canadian strategy has highlighted the importance of its evaluation using high-quality tools, such as validated questionnaires (Government of Canada, 2017). Multiple factors could influence the success of the strategy and should be measured. One factor involves the physicians’ knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) – in this case, regarding both dementia care and national and subnational dementia strategies. KAP studies have been widely used to inform health innovation and are based on the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991; De Pretto, Acreman, Ashfold, Mohankumar, & Campos-Arceiz, Reference De Pretto, Acreman, Ashfold, Mohankumar and Campos-Arceiz2015).

However, few questionnaires that measure the KAP of family physicians exist to monitor the implementation and measure the impact of a dementia strategy. Existing questionnaires appear to have limitations, such as (a) examining only one process of care (e.g., detection, diagnosis, or treatment) (Bedard, Gibbons, Lambert-Belanger, & Riendeau, Reference Bedard, Gibbons, Lambert-Belanger and Riendeau2014; Boustani et al., Reference Boustani, Justiss, Frame, Austrom, Perkins, Cai and Hendrie2011; Doherty, Hawke, Kearns, & Kelly, Reference Doherty, Hawke, Kearns and Kelly2015; Hillmer, Krahn, Hillmer, Pariser, & Naglie, Reference Hillmer, Krahn, Hillmer, Pariser and Naglie2006; Iracleous et al., Reference Iracleous, Nie, Tracy, Moineddin, Ismail, Shulman and Upshur2010; Milne, Hamilton-West, & Hatzidimitriadou, Reference Milne, Hamilton-West and Hatzidimitriadou2005; Pentzek, Fuchs, Abholz, & Wollny, Reference Pentzek, Fuchs, Abholz and Wollny2011; Russ, Calvert, & Morling, Reference Russ, Calvert and Morling2013); (b) or examining only one theme (such as knowledge, attitude, or practice) (Boustani et al., Reference Boustani, Justiss, Frame, Austrom, Perkins, Cai and Hendrie2011; Kaduszkiewicz, Wiese, & van den Bussche, Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Wiese and van den Bussche2008; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Hamilton-West and Hatzidimitriadou2005; Pakzad, Bourque, Gallant, Donovan, & Sepehry, Reference Pakzad, Bourque, Gallant, Donovan and Sepehry2016; Pentzek et al., Reference Pentzek, Fuchs, Abholz and Wollny2011); (c) or having not been formally validated (Ahmad, Orrell, Iliffe, & Gracie, Reference Ahmad, Orrell, Iliffe and Gracie2010; Banjo, Nadler, & Reiner, Reference Banjo, Nadler and Reiner2010; Gaboreau et al., Reference Gaboreau, Imbert, Jacquet, Paumier, Couturier and Gavazzi2014; Iracleous et al., Reference Iracleous, Nie, Tracy, Moineddin, Ismail, Shulman and Upshur2010; Millard & Baune, Reference Millard and Baune2009). The Quebec Alzheimer Plan (QAP, described in Vedel, Sourial, Arsenault-Lapierre, Godard-Sebillotte, & Bergman, Reference Vedel, Sourial, Arsenault-Lapierre, Godard-Sebillotte and Bergman2019), however, is based in primary care and includes a rigorous evaluation plan, which offers an ideal opportunity to develop and validate a comprehensive questionnaire.

The objective of this study was to develop and validate a suitably comprehensive questionnaire to measure family physicians’ KAP regarding dementia care and the physicians’ attitude towards the QAP.

Methods

Setting

The QAP focuses on the capacity of primary health care clinicians to care for patients with dementia. This plan has been deployed in family medicine groups (FMGs), which were implemented during the primary care reform in Quebec. FMGs are composed of multidisciplinary teams, where six to 12 family physicians working in close collaboration with nurses are the gatekeepers of approximately 1,000–2,000 patients per physician (Diop et al., Reference Diop, Fiset-Laniel, Provost, Tousignant, Borges Da Silva, Ouimet and Strumpf2017; Strumpf et al., Reference Strumpf, Levesque, Coyle, Hutchison, Barnes and Wedel2012; Strumpf, Ammi, Diop, Fiset-Laniel, & Tousignant, Reference Strumpf, Ammi, Diop, Fiset-Laniel and Tousignant2017). In 2011, the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services called for volunteer FMGs across the province who wanted to implement the QAP. These FMGs received funds, training, and protocols. The 42 FMGs selected by the Ministry of Health and Social Services started implementing the plan in 2013 (details of the QAP are described in Vedel et al., Reference Vedel, Sourial, Arsenault-Lapierre, Godard-Sebillotte and Bergman2019).

Questionnaire Development and Distribution

The construction of our questionnaire was informed by KAP studies and based on the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991). We performed a rapid review of the literature to identify existing questionnaires addressing five key concepts (attitudes, knowledge, practices, primary care, and dementia) published between 2005 and 2014 in English or French and indexed on Medline. The criteria for inclusion were (a) to measure all care processes (detection, diagnosis, and treatment), (b) to feature all three themes (KAP), and (c) to be validated. We identified a total of 31 articles on KAP questionnaires but they did not adequately address our criteria. We then asked researchers within the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging team to identify any questionnaires that were not identified through the search strategy and that covered all or most of our criteria. One consortium researcher (SP) proposed her questionnaire that met all our criteria (which has now been published: Pakzad et al., Reference Pakzad, Bourque, Gallant, Donovan and Sepehry2016). Working from the French version of the Pakzad’s questionnaire, we adapted items to match the Quebec context with the presence of FMGs. We added items to measure KAP in the three concepts of detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Finally, we added new items to better span the care continuum and to evaluate physicians’ attitudes towards the QAP (Helfrich, Weiner, McKinney, & Minasian, Reference Helfrich, Weiner, McKinney and Minasian2007; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, 2015).

To make the questionnaire available to both English- and French-speaking physicians in Quebec, and to ensure linguistic and cultural validity of both versions, we first asked a native English-speaking translator to translate the questionnaire from French to English. Then, we performed an evaluation of this translation with a native French speaker and with a bilingual speaker, both expert researchers in dementia, and a French-speaking translator familiar with the tool. Finally, once both versions were deemed equivalent, three types of validity and reliability (content validity, construct validity, and internal consistency) were assessed with French and English participants.

We examined the content validity of the questionnaire, and its acceptability, using cognitive interviewing with nine experts and four end users (Willis, Reference Willis2004). The experts included six primary care researchers and three clinician-researchers. The end users were all FMG physicians. During individual interviews, we asked if the questions and the instructions were clear; the proposed answers, appropriate; and if there were any missing questions. The questionnaire was revised after each round of content validation with experts and end users (see supplementary Appendix 1 available online).

Physicians working at least one day a week and caring for patients aged 65 and older were considered eligible to complete a questionnaire. Resident physicians were not eligible. Eligibility was determined, in most cases, by information provided by the medical director or the contact person. Because this was not always possible, especially in larger FMGs, we assessed the physicians’ eligibility with an initial set of questions on the questionnaire itself. Physicians satisfying the eligibility criteria were then instructed to proceed with the questionnaire.

To maximise our response rate, we adapted our distribution strategy to each FMG, depending on their preference and habits. We first asked the medical director who, in their FMG, was best positioned to help with the distribution. We then asked this contact person in each FMG to provide a list of all their practicing physicians. To minimise burden to the staff, we recommended to the contact person that physicians individually fill out the questionnaire during statutory meetings, or that the questionnaire be distributed to their internal mailbox. In some rare cases, the contact person preferred that the questionnaires be sent by email.

A personalised package was prepared and sent to each physician on the list between May 2014 and May 2015. This package included a copy of the questionnaire, along with a letter explaining the study and two copies of the consent form. In the accompanying letter, physicians were told that this was a questionnaire regarding their knowledge, practices, and attitudes regarding dementia and the QAP, in which their FMG was participating. We instructed physicians to give the completed questionnaire back to the contact person. Once questionnaires were collected, we organised the delivery of the questionnaires from the FMGs to our research centre. We confirmed the eligibility of respondents after receiving completed questionnaires. We performed multiple phone and email reminders with the contact person to maximise the response rate and confirm eligibility of non-respondents.

Analysis

Demographic characteristics of the family physicians who completed the questionnaire were described using means and proportions, as appropriate. As it was not possible to determine the eligibility of the physician before sending the questionnaires, we estimated the response rate by applying the proportion of known non-eligible cases to the overall number of questionnaires initially mailed.

To assess the construct validity and reliability of our questionnaire, we calculated the factor structure and internal consistency of the questionnaire respectively. We conducted an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to determine the underlying factor structure (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin1999). Prior to the EFA, we re-coded answers to negatively stated questions (negatively stated questions were inserted to minimise extreme response bias or acquiescent bias), and we elaborated an a priori factor structure based on clinical judgement and the item-by-item correlation matrix based on the raw survey data. We assessed the proportion of missing data for each item in order to ascertain whether missing data were distributed evenly across items or concentrated within a few items (Fonseca, Costa, Lencastre, & Tavares, Reference Fonseca, Costa, Lencastre and Tavares2013). We imputed the missing data prior to the EFA via the expectation-maximisation algorithm (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, Reference Dempster, Laird and Rubin1977), which uses an iterative estimation approach to obtain consistent estimates of the missing data under the assumption of normality. Items that were sub-questions (questions dependent on the response to a parent question) or demographic questions were left out of the EFA. We used an oblique promax rotation to allow for correlations between factors. We iteratively eliminated items that had a low loading (< 0.3) or were considered poorly understood or designed items based on the feedback from participants.

To determine the number of factors to retain, we used several objective and graphical measures: the Kaiser criterion (retain all factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1, a minimum explained variance of 75%, the scree plot, residual correlations, and a minimum of three items per factor to ensure stability of the solution) (Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum, & Strahan, Reference Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum and Strahan1999). To facilitate interpretation of the factor solution, we displayed only loadings above the threshold of 0.3 as per convention (Kline, Reference Kline2014). We produced an inter-item correlation matrix for each factor to verify that each item was not too weakly (less than 0.2) or too highly (greater than 0.9) correlated with other items in the factor. As we used a method that allowed for factors to be correlated together, we also assessed the pairwise correlation between factors. To further validate our final factor solution, we presented the results and sought feedback from the participating FMGs, clinicians, and decision-makers at the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services. Our factor solution was presented to and discussed with clinicians and decision-makers at four different meetings in the fall of 2015. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the internal consistency within each factor (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951).

Ethics

The study, questionnaire, and consent forms were approved by the research ethics board of the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, as well as by the ethics committee affiliated with each participating FMG. We obtained institutional authorisation from each regional health organisation where applicable.

Results

Questionnaire Development and Distribution

We sent the 83-item questionnaire (after the second round of validation; see online Appendix 1) to 42 FMGs taking part in the pilot phase of the QAP. Of these, 38 FMGs consented to participate in this study. Two FMGs withdrew from the QAP, and two others chose not to participate in the study. Overall, we sent 646 questionnaires with an estimated response rate of 68 per cent (based on the estimation of non-eligibility). The demographics of physicians who returned a questionnaire are described in Table 1.

Table 1: Self-reported demographics of the family physicians who returned a questionnaire (n = 369)

After a third round of validation (online Appendix 1), the questionnaire contained 64 items (12 items for demographics characteristics and 52 items related to KAP). Of the 52 items related to KAP, most (n = 47) were on a 4-point Likert scale (1, “disagree”; 2, “somewhat disagree”; 3, “somewhat agree”; and 4, “agree”). This 4-point scale, without a neutral category, was chosen to force users to form an opinion and minimise acquiescence bias (Allen & Seaman, Reference Allen and Seaman2007; Ray, Reference Ray1990). Five items on attitudes towards the QAP were on a 10-point Likert scale (e.g., 1, “not at all beneficial” to 10, “very beneficial”).

Construct Validation and Reliability

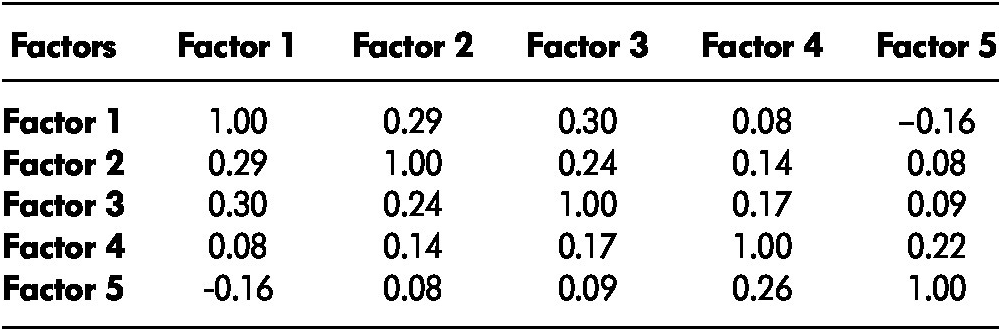

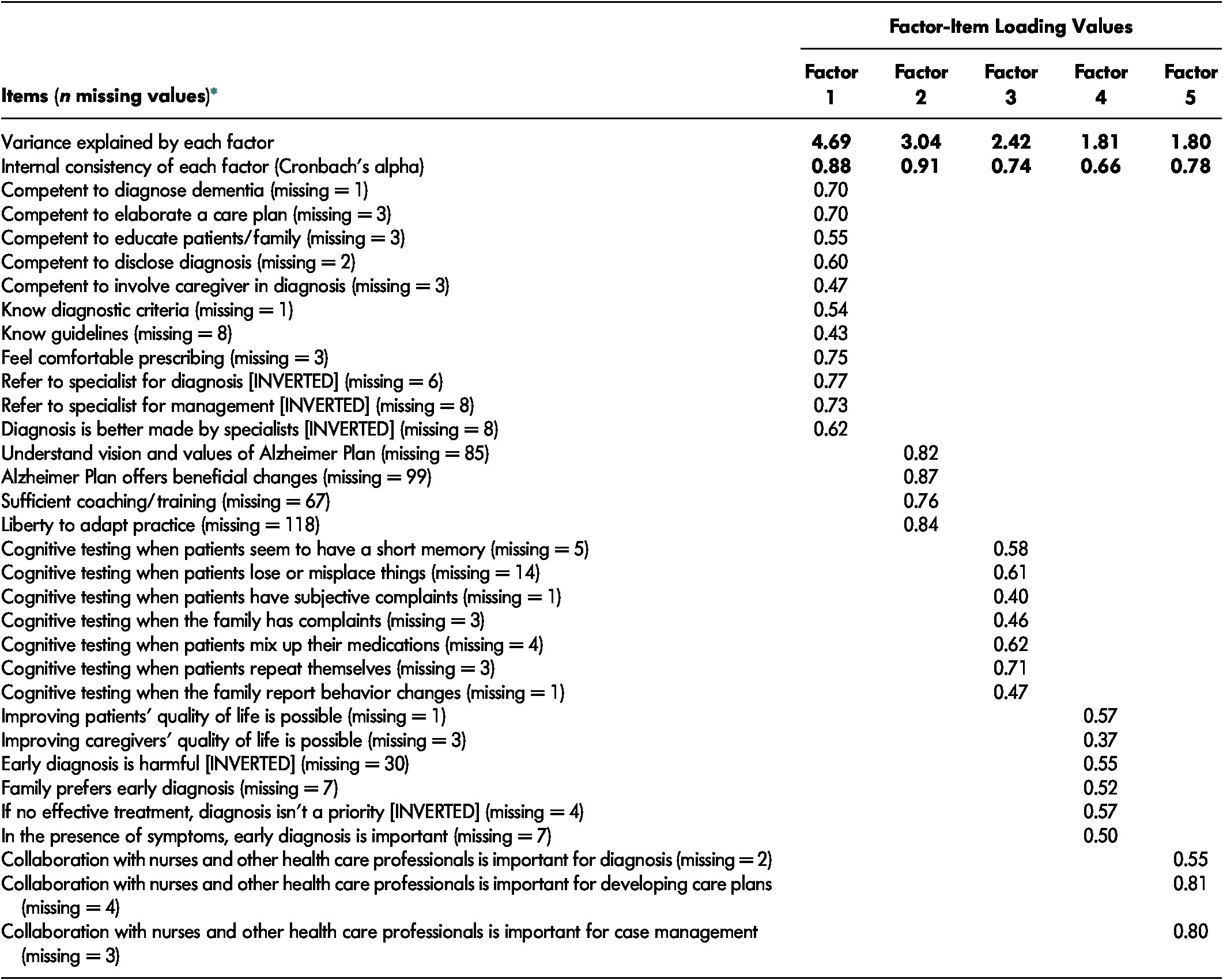

All 64 questionnaire items had a low rate of missing data (0% to 8%), except four items related to attitudes towards the QAP (18% to 32%). Sub-questions related to KAP (n = 16) and demographic questions (n = 12) were excluded from the EFA. The EFA was thus performed on 36 items. Items showed good discrimination across factors with moderate (> 0.40) to high (> 0.70) item-to-factor loading. Five items were eliminated due to poor loading. In total, 31 items were retained. Although seven factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, five factors explained 77 per cent of the variance, met the inflection point of the scree plot (see supplementary Appendix 2, available online), and had low residual correlations. Five factors were thus retained. We labelled Factor 1, “perceived competency and knowledge in dementia care” (11 items); Factor 2, “attitude towards the QAP” (4 items); Factor 3, “practice” (cognitive evaluation; 7 items); Factor 4, “attitude towards dementia care” (6 items); and Factor 5, “attitude towards collaboration with nurses and other health care professionals” (3 items). We found correlation between factors to be weak, ranging from 8 per cent between factors 1 and 4 to 30.2 per cent between factors 1 and 3 (Table 2). All five factors were also found to be clinically relevant and meaningful by the participating FMGs and decision-makers from the Ministry of Health.

Table 2: Inter-factor correlations for the five retained factors

Note. Factor 1: Perceived competency and knowledge in dementia care; Factor 2: Attitudes towards Alzheimer Plan; Factor 3: Practices (cognitive evaluation); Factor 4: Attitudes towards dementia; Factor 5: Attitudes towards collaboration with nurses and other health care professionals.

The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the items within each factor ranged from 0.66 to 0.91, showing moderate to high reliability between the items and factors (Table 3). A few items showed low inter-item correlations, especially in factors 3 and 4. No items were too highly correlated (see supplementary Appendix 3, available online).

Table 3: Factor loading values for each of 31 items on respective factors, explained variance, and internal consistency of each factor

Note. *Missing values were imputed using the expectation maximization algorithm. Factor 1: Perceived competency and knowledge in dementia care; Factor 2: Attitudes towards Alzheimer Plan; Factor 3: Practices (cognitive evaluation); Factor 4: Attitudes towards dementia; Factor 5: Attitudes towards collaboration with nurses and other health care professionals. Only loadings above 0.3 are displayed.

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of missing data on the robustness of the factor solution. Using the subset of data with no missing data on any item, we found the factor solution to be similar except for two items, “Improving patients’ quality of life is possible” and “Improving caregivers’ quality of life is possible”, which loaded onto Factor 5, “Attitudes towards collaboration with nurses”. We then conducted the EFA using the raw data on 27 of the 31 items after removing the four items with the highest proportion of missing data, which incidentally corresponded to the items within Factor 2. The 27 items loaded onto the same four factors as in the primary analysis. The final version of the KAP-Primary Dementia Care questionnaire is presented in supplementary Appendix 4, available online.

Discussion

Using high standards of instrument development and validation, we developed a questionnaire on the KAP of family physicians regarding dementia care and the QAP, providing a tool to measure progress in the implementation of dementia strategies in primary care and their impact.

Our questionnaire contributes to the literature on KAP in family physicians regarding dementia care as it addresses elements of detection, diagnosis, and treatment through the perspectives of physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Our questionnaire expands on previous questionnaires measuring practices and attitudes towards dementia in family physicians (Pakzad et al., Reference Pakzad, Bourque, Gallant, Donovan and Sepehry2016). Furthermore, elements relating to the family physicians’ perceived competency and knowledge, their attitudes towards their collaboration with nurses, and the Alzheimer Plan were added in our questionnaire.

Prior questionnaires concerning family physicians’ attitudes, knowledge, or practice on dementia have not successfully addressed all three themes throughout the care process (Bedard et al., Reference Bedard, Gibbons, Lambert-Belanger and Riendeau2014; Boustani et al., Reference Boustani, Justiss, Frame, Austrom, Perkins, Cai and Hendrie2011; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Hawke, Kearns and Kelly2015; Hillmer et al., Reference Hillmer, Krahn, Hillmer, Pariser and Naglie2006; Iracleous et al., Reference Iracleous, Nie, Tracy, Moineddin, Ismail, Shulman and Upshur2010; Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Wiese and van den Bussche2008; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Hamilton-West and Hatzidimitriadou2005; Pentzek et al., Reference Pentzek, Fuchs, Abholz and Wollny2011; Russ et al., Reference Russ, Calvert and Morling2013). Our questionnaire is the first to measure the physicians’ attitudes towards a dementia strategy. Determining attitudes regarding a dementia strategy is important because it is likely that such attitudes impact the success of any such strategy (Holt, Helfrich, Hall, & Weiner, Reference Holt, Helfrich, Hall and Weiner2010; Kaplan, Greenfield, & Ware Jr, Reference Kaplan, Greenfield and Ware1989). This knowledge will enable decision-makers who are implementing dementia strategies in primary care to evaluate whether physicians understand the mission and values of the strategy and can effectively act on it.

The present study presents significant strengths. The validity of our questionnaire is supported by an extensive review of instruments, the use of an iterative process with a panel of experts as well as family physicians, and validation of our factor solution with key stakeholders. Our questionnaire was tested in a large sample of physicians and a wide range of practices, rural and urban, throughout the province. Socio-demographics characteristics of the sample (self-reported rural/urban practice, sex, and language ratio) suggest a good representation of the respondents to the general population of family physicians in Quebec. In our study, we had a higher proportion of female physicians than in Quebec physician population data from 2002 and 2005 (61% vs. 48%) (Coyle, Strumpf, Fiset-Laniel, Tousignant, & Roy, Reference Coyle, Strumpf, Fiset-Laniel, Tousignant and Roy2014). However, more recent Quebec population data shows rates closer to rates reported in our study (56%) (Scott’s Medical Database, 2019). Although this finding is consistent with the fact that women seem to make up an increasingly larger proportion of the family physicians in Canada (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019), we cannot entirely rule out the existence of a response bias, whereby female physicians respond more often to surveys than do male physicians (Cull, O’Connor, Sharp, & Tang, Reference Cull, O’Connor, Sharp and Tang2005). We also found a higher proportion of family physicians working in both languages compared to the proportion of health professionals (10.3% vs. 4.4%) (Statistics Canada, 2013) and lower urban practices than what has been found in population data (Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, Strumpf, Fiset-Laniel, Tousignant and Roy2014). Our study sample also closely reflected the average number of years of practice (Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, Strumpf, Fiset-Laniel, Tousignant and Roy2014) and the proportion of French speakers in the Quebec population (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Most strikingly, the high response rate (68%) we obtained is superior to what has been reported in similar literature (27% to 63%). The high response rate may have resulted from the use of recognised strategies of questionnaire distribution and the fact that we ensured a close collaboration with the medical directors to facilitate distribution of the questionnaires (VanGeest, Johnson, & Welch, Reference VanGeest, Johnson and Welch2007). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the factor solution. Finally, all but one factor included at least four items, which is recognised as a high standard (Fabrigar et al., Reference Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum and Strahan1999).

In terms of limitations, there is a possibility that the motivation of the FMGs to participate in the QAP may have consisted of a selection bias. Similarly, our sample represents around 8 per cent of family physicians working in FMGs in Quebec may constitute a representation bias (Bergman, Dove, & Weinstock, Reference Bergman, Dove and Weinstock2017; College des Medicins Du Quebec, 2018). Another limitation is that one factor (“Attitudes towards collaboration with other health care professionals”) included only three items. In addition, low inter-item correlations and moderate internal consistency in factors 3 and 4 should be considered in the interpretation and may merit further consideration. Finally, the validation of the questionnaire was done in the Quebec context only. Ideally, the research should be replicated in other provinces where dementia strategies have been developed and implemented.

Conclusion

This questionnaire offers a comprehensive, validated measure of family physicians’ KAP regarding dementia care and strategies. This questionnaire could be used by researchers, managers, and decision-makers to assess the capacity of family physicians to detect, diagnose, treat, and manage patients with dementia. This questionnaire could also be used to monitor the progress of dementia strategies in primary health care and to measure its impact on family physicians’ KAP.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000069

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Author Contributions

GAL contributed to the conception of the study, design, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. NS contributed to the analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. SP contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. MH contributed to the interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. YC contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. HB contributed to the design, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation; and IV contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work received funding from the Pfizer-Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux grant, “Evaluation des projets d’implantation ciblée de services intégrés en première ligne pour les personnes présentant des troubles cognitifs liés au vieillissement et leurs proches” (2013–2014), and the Canadian Consortium for Neurodegeneration and Aging (CCNA) grant, “Assessing care models implemented in primary health care for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders” (2014–2019). The CCNA is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research with funding from several partners.