Where Did the Revolution Go? An Introduction

Where did the revolution go? The main puzzle – revived by the recent events of the so-called Arab Spring – is the apparently sudden disappearance from the political sphere of the large social movements that contributed to episodes of democratization. Media, activists, and scholars have often used terms like Velvet Revolution or Jasmine Revolution – but also Carnation Revolution or Orange Revolution – to describe regime transition involving massive participation from below. However, with the emergence of political liberalization or even the installation of a democratic regime, observers are often surprised to note the sudden emptiness of the once-full streets, and even the rapid loss of influence of the oppositional leaders, once the new regime has been installed. Even more, those who fought for democracy seem quickly disappointed by the results of their own struggles, and choose to exit the movement. But is the disappearance real, or just an optical illusion, given the focus of mass media and scholarship on electoral processes and “normal politics”? Does it always happen, or only under some circumstances? Are those who struggled for big changes bound to be disappointed by the slow pace of transformation? And which mechanisms are activated and deactivated during the rise and fall of episodes of democratization?

These questions – which have rarely been addressed in the social science literature – refer, in their essence, to the effects of transition processes on consolidated democracy. The main theoretical frame of the research presented in this volume builds upon reflections on outcomes in the cognate fields of democratization and social movement studies, although read through the lens of an approach that aims at reconstructing processes rather than identifying causes. I also bring in studies on revolutions, even if to a more limited extent. I do this because, although it would be inappropriate to define the episodes mentioned above as revolutions, some of them imply sudden breaks through mass mobilizations that can indeed be illuminated by that field of study. I believe, in fact, that there is much to gain in this theoretical endeavor in order to move toward systematic models for understanding social movements’ impacts in terms of big transformations. While social movement studies have systematically addressed the crucial issues of their effects at the structural, political, and cultural levels, they have mainly adopted static models, singling out correlations but not causal mechanisms. Moreover, they have focused mainly on incremental changes in “normal” times. In contrast, democratization studies, even if largely overlooking social movements in favor of the elites, have focused on the strategic choices of the different actors, linking them to their preferences and interests. Finally, recent studies of revolutions have contributed to our understanding of moments of (big) changes through attention to the emergence of new actors and to their coalition-building, internal divisions, and dilemmas within a context of rapid transformation.

In combining these literatures, I aim at providing an understanding of the effects of mobilizations for democracy on social movements’ actual and potential characteristics – an understanding that is dynamic, recognizing the relational nature of contention; constructed, stating the importance of cognitive assessments of a situation; and emergent, looking at the transformative emotional intensity of some events. My main assumption is that the forms and paths of mobilization during the episodes of mobilization for democracy have an effect on some of the qualities of the ensuing regime. In particular, I expect the participation of social movements in democratization processes to have important consequences in terms of specific civil, political, and social rights – as the call for a break with the past and increased rights for the citizens will be louder than in regime transitions that happen mainly through elite pacts. Episodes of mobilizations for democracy in fact represent critical junctures, which then affect democratic developments toward a higher or lower quality of citizenship rights. This means that even when these movements disappear from the mass-mediated public sphere, and even when they are mourned by their former activists as being in decline, we can still find traces of their effects on the recognition of citizens’ rights to protest, the presence of channels of institutional access, and sensitivity to social justice.

This approach implies some caveats vis-à-vis existing literature that aims at explaining democratization and its quality, on the one hand, or rapid, revolutionary changes, on the other. First of all, my aim is not to assess democratic qualities in general – other researchers have already done so, using a variety of qualitative and quantitative techniques. Moreover, I do not aim at providing general explanatory models (parsimonious or otherwise) of the success or failure of democratization processes, with or without mass mobilization, as other literature on democratization does. Admittedly, there are therefore many conditions that affect the quality of democracy that I do not address. Rather, I would aim at singling out some causal mechanisms that, in the cases I studied, intervened on both the evolution of protest waves and their legacies. While democratization studies as well as studies of revolutions tend to neatly distinguish positive cases from negative ones, I address much more fuzzy evolutions. As social movement studies have often suggested, the effects of contentious waves are complex, never fully meeting the aspirations of those who protest, but rarely leaving things unchanged. In addition, while effects can happen at the policy level, they often develop first in terms of culture, evolving in the long term, with jumps and reversals. This is all the more relevant when looking at democratization – an extended process that in other epochs required many steps in a long process, but today is often expected to happen in a few short weeks.

While social movement studies allow for useful reflections on the long-term and complex assessment of movement outcomes, I would also like to go beyond some expectations present in that literature. First and foremost, I will not just look at protest as contributing to explaining policy or cultural changes. Rather, I want to investigate how protest actors – particularly social movements – also develop their own resources in action, not only using previously accumulated resources but also acquiring new ones; and not only exploiting existing opportunities but also opening new windows by breaking former alliances and by challenging the expectations upon which they were based. Protests, particularly the intense moments of mobilization for democracy, are therefore understood as eventful, given their capacity to transform structures through relational, emotional, and cognitive mechanisms (Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996; della Porta Reference della Porta2013b, Reference della Porta2014a;). As I argued in a previous work (della Porta Reference della Porta2014a), the transformative power of protest can be seen when analyzing episodes of democratization, defined, following Ruth Collier (Reference Collier1999), as moments toward a process of democratization, rather than necessarily bringing about a transition to democracy.

Without assuming that democratization is always produced from below, I have singled out – in the cases I have analyzed and without pretense of being exhaustive – different paths of democratization by looking at the ways in which masses interact with elites, and protest with bargaining. In all of these paths, social movement organizations are considered among the important actors in a complex field: they stage protests that have an impact in steering the change. Their relevance, however, lies in the fluid processes of breaking and recomposing, mobilizing and negotiating (Glenn Reference Glenn2001). In particular, I identified eventful democratization as defining cases in which authoritarian regimes break down following – often short but intense – waves of protest. Recognizing the particular power of some transformative events (Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996), I have addressed them as part of broader mobilization processes, including the multitude of less visible, but still important, protests that surround them (della Porta Reference della Porta2014a). While protests in eventful democratization develop from the interaction between growing resources of contestation and closed opportunities, social movements are not irrelevant players in the other two paths I singled out. First of all, when opportunities open up because of elites’ realignment, participated pacts might ensue from the encounter of reformers in institutions and moderates among social movement organizations. Although rarely used, protest is also important here, as a resource to threaten on the negotiating table.Footnote 1 If participated pacts occur in relatively strong civil society that meets emerging opportunities, more troubled democratization paths develop in very repressive regimes that block the development of autonomous associations. In these cases, escalation of violence often follows from the interaction of a suddenly mobilized opposition with a brutal repressive regime. Especially when there are divisions in and defections from security apparatuses, skills and resources for military action fuel coups d’état and civil war dynamics.

Comparing eventful democratization with participated pacts, the claim I discuss in this volume is that the different forms and degrees of participation of social movements during transition, and their positions during the installation of the regime, have an impact on some of the qualities of the ensuing regime. Without taking a deterministic stance, but also without decontextualizing agency, I will suggest some specific mechanisms that link protest for democracy to democratic qualities. This will require us to look at the evolution of the waves of protest that accompany episodes of democratization, singling out relational, affective, and cognitive dimensions in the periods before, during, and after regime transition.

I address these tasks via a research project based on a mixed-methods research design, combining in-depth interviews oriented to an oral history of contentious events in transition and post-transition with protest event analysis, as well as extensive use of secondary sources. Within a most-similar research design, I conduct an infra-area comparison of Central Eastern Europe (CEE) (in particular, contrasting Czechoslovakia and the German Democratic Republic [GDR] as cases of eventful democratization, with Poland and Hungary as cases of participated pacts). Additionally, I broaden the scope of the comparison in space and time by looking at two eventful episodes of mobilization for democracy in the Mediterranean and North African region. For this part of the analysis, Tunisia and Egypt will be compared with two purposes in mind. First, looking for similarities within a cross-area, most-different research design, I will examine the extent to which some mechanisms identified in the CEE region are robust enough to travel to the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) area more than twenty years later. Second, a within-area comparison will allow me to shed light on the different outcomes of those mobilizations, with apparently more positive results in terms of citizens’ rights in Tunisia than in Egypt.

The Theoretical Frame: How Mobilization for Democracy Affects Its Qualities

How to understand the trajectory and effects of social movements mobilizing for democracy, as they interact with other actors in complex fields? How to make sense, then, of the results of transition paths on the quality of democracy? In addressing these questions, the focus is on the how rather than the why. In particular, I do not aim at developing a powerful but parsimonious model to explain democratic qualities, as other scholars have done with large numbers of cases and quantitative indicators. Instead, in the search for causal mechanisms that allow understanding how movements for democratization affect the movements to come, I looked for inspiration in three cognate areas of study that have often looked at the same events, but using different analytic lenses: democratization studies, revolution studies, and social movement studies.

Democratization studies have traditionally focused on the successes and failures of attempts to democratize, often searching for scientific law-like statements that might allow identification of the general conditions for democracy. Ever more complex models have been built in an attempt to explain the maximum of variance in the success and failure of democratization attempts. In criticism of a deterministic approach looking for contextual causes, a more strategic orientation looked at the ways in which influential actors played the game of democratization. While social movements and protests tended to be dismissed as of little relevance, or even as dangerous for democracy, the literature on democratization has provided important theoretical and empirical contributions to understanding critical interactions between (mainly elite) actors (for a critical assessment, see Bermeo Reference Bermeo1997).

Revolution studies were initially focused on social revolutions, which affected also the political and economic regimes, thereby transforming relations between the state and the market. Distinguishing neatly between successful and failed cases, studies on revolutions – social ones, at least – define them as “basic transformation of a society’s state and class structures,” “accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979, 4–5). Success is usually understood as “coming to power and holding it long enough to initiate a process of deep structural transformation” (Foran Reference Foran2005, 5). While a deterministic approach initially dominated here as well, a violent break was also considered as a determinant of change. Broadening the field of studies to include a (somewhat stretched) definition of revolution as nonviolent and nonsocial, scholars of revolution also started to address the strategic choices of various actors, including those who claimed to represent the masses. Even if definitional issues are still debated, studies on revolutions contributed to challenge democratization studies through their attention to the conflictual dynamics before, during, and after revolutions, considered as breaking points.

As mentioned, while both fields of study tend to neatly distinguish successes and failures – positive and negative cases – as their explanandum, social movement studies have looked at the effects of mobilization as more ambivalent, complex, and long term. It has long been common to state that the effects of social movements have rarely been addressed in social movement studies, especially given the difficulty in assessing multicausal and long-lasting processes. In particular, the recognition that social movements have often utopian aims has made it difficult to find measures of the degree of success. This narrative is, however, less and less apt to describe a field of research in which outcomes appear more and more as relevant objects of investigation. The very interest in social movements as agents of change has in fact focused attention toward those effects, with much reflection on the possible solutions to methodological challenges. While I built upon these assumptions in the search for the consequences of episodes of mobilization, I also tried to innovate on explanatory approaches that I found either too deterministic or too agency oriented, through an analysis of the more dynamic aspects on the path toward democracy.

In this introductory chapter, I aim at building a theoretical framework that might help readers in understanding the effects of social movements in transition on democratic qualities in consolidation. I attempt to do this by bridging social movement studies with the literatures on democratization and on revolutions, which have indeed looked for the causes of the success and failure of efforts to bring about political and social change. These social science fields have rarely been linked to each other and/or with the social movement theory that, I argue, can provide new lenses to explain how movements’ characteristics at the time of transition might affect the qualities of the ensuing democracy and therefore the future dynamics of protest itself. At the same time, looking at the effects of social movements in terms of democratization (or, sometimes, revolutions) can help to enrich social movement studies, which have rarely addressed these types of effects, focusing instead on long-lasting democracies. Following the contentious politics approach, rather than emphasizing structural determinants, I concentrate on the mechanisms that mediate between structures and action (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001). I attempt in fact to bring into focus the actors’ agency, without losing awareness of the environmental constraints on their desires. In particular, I give leverage to the actors’ perceptions, focusing on social movement activists, as I believe they influenced the movements’ effects as they intervened between the external reality and the action upon it.

What Do We Want to Understand: Institutional Effects of Democratization Paths

My central assumption is that the role of social movements varies in different paths of transition, with consequences for the democratic qualities of the ensuing regimes (della Porta Reference della Porta2014a). In particular, it might be expected that eventful democratization, through social movement participation, enlarges the range of actors that support the new regimes, while pacted transitions remain more exclusive toward citizens’ demands, focusing instead on elite interests.

In order to look at the effects of social movements’ participation in transition on the eventual democratic institutions, we must first conceptualize these effects. The social science literature on democratic quality (or, better, qualities in the plural) has made an important contribution in mapping the specific dimensions on which democracies should be assessed. Summarizing various reflections, Leonardo Morlino (Reference Morlino2012, 197–8) distinguished procedural and substantial dimensions. Procedurally, quality of democracy implies rules of law, including the following:

1. Individual security and civil order.

2. Independent judiciary and a modern justice system.

3. Institutional and administrative capacity to formulate, implement and enforce the law.

4. Effective fight against corruption, illegality and abuse of power by state agencies.

5. Security forces that are respectful of citizen rights and are under civilian control.

To these procedural dimensions, Morlino added two substantive ones: freedom (as translated into political and civil rights) and equality (as translated especially into social rights). In particular, political rights encompass the right to vote, to compete for electoral support, and to be elected to public office (ibid., 204). Civil rights encompass

personal liberty, the right to legal defense, the right to privacy, the freedom to choose one’s place of residence, freedom of movement and residence, the right to expatriate or emigrate, freedom and secrecy of correspondence, freedom of thought and expression, the right to an education, the right to information and a free press, and the freedoms of assembly, association and organization, including political organizations unrelated to trade unions.

Finally, social rights include

rights associated with employment and connected with how the work is carried out, the right to fair pay and time off, and the right to collective bargaining … the right to health or to mental and physical well-being; the right to assistance and social security; the right to work; the right to human dignity; the right to strike; the right to study; the right to healthy surroundings, and, more generally, to the environment and to the protection of the environment; and the right to housing.

We can rephrase these dimensions in terms of sets of citizenship rights. In historical sociology, democracy has been linked to the extension of citizenship rights, typically broken down into categories of civil, political, and social rights. In Marshall’s influential account (Reference Marshall, Marshall and Bottomore1992), civic rights were the first to be achieved, followed by political rights and, with them, the possibility to create pressure for social rights as well. However, more recent analyses have stressed the various possible timings in their development, both for specific social groups and for specific countries (della Porta Reference della Porta2013a). In this sense, they are not necessarily moving in the same direction, as in fact an increase in political rights (and formal democracy) can accompany a decline in social rights. As democratic states do show different achievements on all these sets of rights, an analysis of democratic qualities must first assess and then explain those differences. While various indicators (or proxies) have been chosen (and their own quality discussed) in order to measure democracy, qualitative investigations are also important to complete and understand those data.

Without pretending to assess, let alone explain, all dimensions of democratic quality in all the selected countries, in this work I aim instead at identifying some specific effects that the paths of transition have on the development of the civic, political, and social qualities of the emerging regimes. Following leads from studies of social movements, of revolutions, and of democratization, I want to move, in my argumentation, from structures and strategies to relational dynamics. Charles Tilly has suggested categorizing the scholars working on political violence as idea people, who look at ideologies; behavior people, who stress human genetic heritage; and relational people, who “make transactions among persons and groups much more central than do ideas or behavior people” (Reference Tilly2004, 5). So, he continues, relational people focus their attention “on interpersonal processes that promote, inhibit, or channel collective violence and connect it with nonviolent politics” (ibid., 20; see also McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001, 22–4). This also applies, as I will argue in what follows, to research on contentious politics, more generally, which has considered structures and agency and is now moving toward a more relational perspective – a perspective that is not separate from the first two, but can use some of their insights in order to understand the contextual constraints as well as actors’ strategies within relations.

How to Explain: Structural Constraints and Outcomes

For some time, research on democratization, revolutions, and social movements has stressed the structural conditions for their development. Various approaches have searched for causal explanations, citing socioeconomic, cultural, and political conditions.

The literature on democratization has looked at regime consolidation, linking democratic qualities to some of the characteristics of the previous regimes, as well as at the dynamics of transition. In general, it has singled out several favorable or unfavorable conditions, in some cases extending the reflection to conditions of nonconsolidation. If economic and social factors were initially emphasized, researchers tended to add more and more explanatory dimensions. In a broad synthesis of the determinants of democratization, Jan Teorell (Reference Teorell2010) suggested that, if economic crises, peaceful protests, media proliferation, neighborhood diffusion, and membership in democratic regional organizations contribute to democratization (and foreign interventions work only sometimes), socioeconomic modernization and economic freedom tend to prevent downturns, while volume of trade is negatively linked to democratization. While modernization helps regimes to survive, economic crises trigger democratization processes as they (and, especially, the connected recessionary policies) divide elites, with ensuing private sector defection as well as mass protests on social issues. Failed democratization has been predicted not only by structural conditions of a socioeconomic nature but also by political factors such as the longevity of statehood or the degree of power of the legislative branch, as reversed liberalization is linked to the intervention of a strong executive. The position of the military is especially relevant. Military dictatorships, multiparty autocracies, military regimes, and single-party regimes have different likelihoods and dynamics of democratization (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1997). External powers are also seen as acting to facilitate or jeopardize democratization (Fish and Wittenberg Reference Fish, Wittenberg, Haerpfer, Bernhagen, Inglehart and Welzel2009). Falling dominos have been singled out, as membership in regional organizations as well as diffusion from neighbors promotes democracy, while foreign intervention is only sometimes effective. Military intervention is also of varying influence. More specifically with reference to 1989, reflections addressed the specific difficulties of double or triple transitions, looking at the complications that emerge when a change in political regime overlaps with one at the socioeconomic level and, in some cases, also with transformation in the definition of the nation-state (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Offe Reference Offe1996).

Structural conditions have also been a main focus for the literature on revolutions. Even without referring much to each other, scholars in the fields of democratization and revolution have built mirrored images of what facilitates democratization and what instead supports revolutions, which were initially conceptualized as involving broad and abrupt social changes, often through violent means. Influentially, Theda Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1979) has linked successful social revolutions to some particular socioeconomic and international challenges that the state is not able to address. In her view, the great revolutions in France, Russia, and China emerged when the regime in power could not face external threats, given internal constraints in terms of economic system and elites’ constellations. Research on revolutions has also linked them to accelerated shifts from traditional to modern society. According to Jeff Goodwin (Reference Goodwin2001), revolutionary movements are especially powerful in peripheral societies, when they build large coalitions with strong international allies. They tend to emerge where regimes are weak (in terms of policing capacity and infrastructural power), unpopular (because of the economic and social arrangements they support), and using high levels of repression (indiscriminate, but not overwhelming). They are more likely to prevail when corrupt and personalistic rules divide the incumbent elites. In general, in fact, people do not support revolutions if they believe that there are alternative paths, but do engage in them if they see no other way out (ibid., 25–6). Looking for necessary and sufficient causes, Foran (Reference Foran2005, 14) suggested that successful revolutions require dependent development, repressive exclusionary and personalist regimes, and economic downturn, as well as the specific political culture of the opposition, defined as “the diverse and complex value systems existing among various groups and classes which are drawn upon to make sense of the ‘structural’ changes going on around them” (ibid., 18). While these analyses focus on revolutionary success in terms of achieving and keeping state power, the democratic qualities of the ensuing regimes have been addressed by research on nonviolent revolutions (or civil resistance), which pointed at the distribution of power within the elites –the military in particular – in determining the chances that a democratic regime will unfold (Nepstad Reference Nepstad2011).

Explanations on the policy effects of social movements have also looked at structural stable conditions (such as opportunities in politics and in the administration) as well as at the (more conjunctural) availability of allies. Social movements are supposed to be more successful in reaching their aims when they have more channels of access to decision makers, thanks to a high degree of functional distribution of power or territorial decentralization, as well as availability of instruments of direct democracy (Kriesi Reference Kriesi1991). It has been also observed, however, that all of those channels are also available for social movement adversaries, with the possibility then to oppose or reverse social movements’ successes (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986). Besides obtaining favorable laws, implementation of the decisions is a most fundamental step, in which the characteristics of the public administration also play an important role. Finally, having sympathetic parties in power is said to improve the chance that social movements will achieve their goals (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994; della Porta Reference della Porta1995). From an economic point of view, not only are times of economic growth of course more favorable to the concession of social rights than are times of economic crisis, but the type of relations between the state and the market also sets constraints upon movements’ achievements (della Porta Reference della Porta2013a, Reference della Porta2015). Specific traditions embedded in existing institutions (such as the citizenship regime or welfare institutions) also affect responses to movement demands (Giugni, Bosi, and Uba Reference Giugni, Bosi and Uba2013).

While, as we will see, my research tends to confirm that some of the mentioned – socioeconomic, political, cultural – conditions are indeed structuring actors’ choices as well as the effects of those choices, it would be too deterministic to consider them as either unchangeable or unaffected by the strategies that different actors adopt during critical moments, and/or by broader relations in the social and political arenas. Instead, it is often under harsh conditions or closed opportunities (defined as threats) that people find the energy to mobilize. Rather than seeing preconditions as fixed, then, one should consider them as part of a contextual background that constrains but also motivates action. Combining the insights from the various fields of research, one can expect democratic qualities to be higher when socioeconomic conditions are improving and political structures are open and autonomous from powerful external actors (such as the military).

How to Explain: Strategic Choices and Democratic Consolidation

Uneasy with a deterministic view, all three areas of study I have mentioned have indeed moved toward a recognition of the role of agency as shaping the structures themselves. In this turn, scholars of democratization, revolutions, and social movements have elaborated some concepts that might be usefully integrated within a relational perspective, with a focus on the dynamic process of interactions between different actors rather than on static causes.

A structuralist bias in the traditional vision of democratization has been strongly criticized by the transitologist approach, which stresses instead the dynamic nature of the process, while focusing on elite strategies and behavior (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell and Schmitter1986; Higley and Gunther Reference Higley and Gunther1992). With this turn, social science reflection on democratization processes has indeed pointed at the importance of actors’ strategies, choices, and actions, especially in moments of transformation when contingency plays a role, solutions are open-ended, and social dynamics are underdetermined (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell and Schmitter1986; Beissinger Reference Beissinger2002). This explains the expectation that, especially in these moments, historical processes tend to be more sensitive to individual agency. In times of uncertainty, the predispositions of elites, in particular their concern for their future reputation, are seen as determining whether democratization occurs at all. In this narrative, “Individual heroics may in fact be key: the ‘catalyst’ for the process of democratization comes, not from a debt crisis or rampant inflation or some major crisis of industrialization, but from gestures by exemplary individuals who begin testing the boundaries of behavior” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo, O’Donnell, Schmitter, Whitehead, O’Donnell, Schmitter, Whitehead, O’Donnell, Schmitter, Whitehead, O’Donnell and Schmitter1990, 361). Through game theory, negotiations toward democracy are explained by the attitudes of defenders and challengers of the regime, the preferences of the public as well as the positions of actors such as the military or the church, and international pressures (Casper and Taylor Reference Casper and Taylor1996). Of utmost importance are considered the attitudes of elites, their availability to encapsulate conflicts, and their capacity to work within democratic institutions. Relevant factors for consolidation include the extent to which the military feels threatened; the attitudes of the judiciary; and the position of public service and civil society (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1997).

Opinions diverge, however, on the role of movements in the beginning of the consolidation phase. In fact, literature on transition has traditionally pointed at the importance of an agreement between moderate forces, among both challengers and incumbents, with a privileged role recognized to institutional actors. According to the moderation thesis, consolidation is easier when civil society is not mobilized (or at least demobilizes), leaving space for the emergence of representative institutions (Huntington Reference Huntington1991, 589). Moderation was therefore seen as a positive evolution, as the attitudes and goals of the various actors change along the process. In a comparison of democratic consolidation in southern Europe, Leonardo Morlino (Reference Morlino1998) observed, in particular, the need to strengthen political parties, rather than social movement organizations. However, in other analyses, protest, especially if multiclass, is considered as important in promoting democracy (e.g., Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1997; Bermeo Reference Bermeo1997).

In comparison to mainstream democratization studies, research on revolutions tends to develop different expectations in terms of the role of pressures from below, as a revolutionary break is often considered as a necessary condition for social and political change. Looking at strategic choices in long-lasting processes and criticizing the structuralism of Skocpol’s model, a new generation of scholars of revolution stressed the role of actors’ strategies in determining the forms and outcomes of political processes. In particular, attention developed on “issues of agency, political culture and coalitions, and the dimensions of ethnicity (or ‘race’), class and gender” (Foran Reference Foran2005, 13). These researchers analyze the specific preferences and capacities of social classes such as, for example, the unwillingness of the bourgeoisie to modernize or the availability of peasants and workers to build coalitions (e.g., Paige Reference Paige1997). Ideology is considered as playing a central role in the stabilization of revolutionary coalitions (Parsa Reference Parsa2000), which are expected to be particularly successful when they oppose authoritarian states that adopt exclusive strategies even toward the middle and upper classes (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001, 27). With the broadening of reflections to nonviolent revolutions, attention focused in particular on the negative effects of the use of violence on the democratic quality of the regime (Chenoweth and Stephan Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011; Nepstad Reference Nepstad2011). Peaceful forms of noncooperation are seen instead as undermining the rulers without threatening the security force, and therefore facilitating their defection from the regime.

If social movement studies have long shied away from explaining protest effects in terms of the strategic choices of various actors, preferring more structural types of explanation, there has been, however, some debate on the role of the opposition’s organizational strategies in facilitating or thwarting success. In particular, scholars have focused on organizational dilemmas, as a certain level of organizational resources seems necessary for collective mobilization (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977). Thinking small, and a moderate repertoire of protest, have been proved effective in achieving specific aims (Gamson Reference Gamson1990). However, organizational trends such as professionalization and bureaucratization are considered dangerous for a social movement, alienating rank-and-file supporters and reducing the disruptive capacity of poor people’s movements (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1977). Particularly relevant here is the issue of how social movement organizations address strategic dilemmas (Jasper Reference Jasper2004). Here as well, the use of violent repertoires is seen as risky in terms of alienation of potential allies as well as public support (della Porta Reference della Porta1995, Reference della Porta2013b).

In sum, combining the three fields, one could expect democratic qualities after transition to be higher when elites and challenges cooperate in a peaceful way. However, the development of strategic preferences toward moderation or radicalization, compromising or breaking up in itself needs to be explained. Often, the effects of specific strategic preferences are in fact influenced by the context, with violent rebellions leading to democracy under conditions of high exploitation (Wood Reference Wood2000). Focusing attention on the contrast between structure and agency can in fact be misleading if we do not consider the relations between the different actors.

Consolidation and Protest: A Dynamic Approach

Following a relational perspective, I shall suggest that forms of action emerge, and are transformed, in the course of physical and symbolic interactions between social movements and their opponents, but also with their potential allies. Changes take place in encounters between social movements and authorities, but also in countermovements, in a series of reciprocal adjustments. Within this relational perspective, I suggest that the types of interactions that develop during transitions have an impact on the evolution of protest during consolidation. Regime transitions, as critical junctures, bring about important changes that then, path-dependently, structure the characteristics of the new regime. The characteristics of social movement participation have a specific relevance for the development of inclusive forms of democracy. In this research, I am in fact especially interested in reflections (and empirical evidence) on the effects in terms of democratic qualities of paths of democratization, as influenced by social movements’ participation in them. I suggest that this assumption is relevant from the theoretical point of view, as well as being backed by some – admittedly not systematic – empirical evidence.

Although with different emphases and in different combinations, the three fields of knowledge I have reviewed so far have in common an increasing interest in agency over structure, as well as a growing preference for processual rather than deterministic explanations. The capacity of collective actors to strategize and make rational decisions in times of intense transformation has been challenged, however, by a relational vision that considers the complex dynamics of interactions between different actors and their mechanisms. Looking from the macro perspective, democratization processes have indeed been considered as underdetermined moments, as they fell out of routines and institutional arrangements. From both the meso and the micro perspectives, assessments about other collective and/or individual actors’ behavior are difficult to make. Decisions are therefore made – as some protagonists have mentioned – “on the run” (rather than allowing time for pausing and thinking) and “betting” on (rather than predicting) other people’s behavior (Kuran Reference Kuran1991; della Porta Reference della Porta2014a). For O’Donnell and Schmitter, transitions from authoritarian rule are indeed illustrations of “underdetermined social change, of large-scale transformations which occur when there are insufficient structural or behavioral parameters to guide and predict the outcome” (Reference O’Donnell and Schmitter1986, 363). In fact, their influential collection of research on the transition from authoritarian rule emphasizes its structural indeterminacy.

Contentious politics during transitions can be seen as eventful moments in which actions change structures (Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996): influencing the relations between elites and challengers, they can be expected to have durable effects (della Porta Reference della Porta2014a). In these critical junctures, in which change is produced not by slow adaptation but by brisk turning points, resources for mobilization are created in action, as emotional, cognitive, and relational processes develop quickly, changing actors’ perspectives and forging new collective identities.

As critical junctures, transitions are therefore turning points that pave the way for changes, which then tend to become resilient. Later, consolidation phases build upon founding moments in which institutional and normative codes are established, with long-lasting effects. Different degrees and forms of contention could develop from specific processes that originate in transition phases. In this vision, in fact, “instead of connecting initial conditions to outcomes, events carry the potential to transform the X–Y relation, neutralizing the reversing effects that initial conditions would have otherwise produced” (Collier and Mazzuca Reference Collier, Mazzuca, Goodwin and Tilly2008, 485).

Once changes are produced via critical junctures, they impact on the relations that are established in new assets (or new regimes). While I do not assume deterministic and unmutable effects of transitions upon consolidation, I expect, however, transition paths to constrain consolidation processes, as “what has happened in an earlier point in time will affect the possible outcomes of a sequence of events occurring at a later point in time” (Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996, 263). So, once a particular outcome occurs, self-reproducing mechanisms tend to cause “the outcome to endure across time, even long after its original purposes have ceased to exist” (Mahoney and Schensul Reference Mahoney, Schensul, Goodwin and Tilly2006, 456). It has in fact been observed that transformations tend to stabilize, as “Once a process (e.g., a revolution) has occurred and acquired a name, both the name and the one or more representations of the process become available as signals, models, threats and/or aspirations for later actors” (Tilly Reference Tilly2006, 421). After a critical juncture stabilizes, changes over time become difficult (Mahoney and Schensul Reference Mahoney, Schensul, Goodwin and Tilly2006, 462) – unless there is a new rupture or disruptive event.

Critical junctures are forms of change endowed with some specific characteristics. As Kenneth Roberts (Reference Roberts2015, 65) noted, “critical junctures are not periods of ‘normal politics’ when institutional continuity or incremental change can be taken for granted. They are periods of crisis or strain that existing policies and institutions are ill-suited to resolve.” In fact, he stated, they produce changes described as abrupt, discontinuous, and path dependent:

Changes are abrupt because critical junctures contain decisive “choice points” when major reforms are debated, policy choices are made, and institutions are created, reconfigured, or displaced. They are discontinuous because they diverge sharply from baseline trajectories of institutional continuity or incremental adaptation; in short, they represent a significant break with established patterns. Finally, change is path dependent because it creates new political alignments and institutional legacies that shape and constrain subsequent political development.

If critical junctures are rooted within structures, they are however open-ended. In this vision, critical junctures are structurally underdetermined as they are characterized by high levels of uncertainty and political contingency. During these periods of crisis, “the range of plausible choices available to powerful political actors expands substantially” (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007, 343). As Roberts (Reference Roberts2015, 13) noted with reference to the neoliberal critical juncture in Latin America,

citizens and social actors influenced outcomes through various types of political mobilization, inside and out of the electoral arena. The complex and contingent political realignments produced by neoliberal critical junctures, then, were not straightforward crystallizations of strategic choices or institutional innovations adopted by political leaders; societal resistance and reactive sequences produced myriad unintended consequences that pushed institutional development (and sometimes decay) along unforeseen paths.

Choice points are particularly important in this sequence since, as exogenous shocks are introduced, the responses by different actors to specific challenges tend to reconstitute relations.

If these are theoretically relevant reasons to focus on eventful protest in the democratization process, empirical research has collected some scattered evidence that justifies a systematic focus on the consequences of choosing particular paths of transition on democratic qualities. Without assuming that transition forms determine once and forever the potential for consolidation as well as the democratic quality of a regime, I argue that moments of fluidity and uncertainties such as transitions shape in fact the access to democratic institutions by different groups in democracy (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell and Schmitter1986; Shain and Linz Reference Shain and Linz1995). Different modes of transition can indeed be expected to have different effects, related to the continuity/discontinuity of the mobilized actors – whether institutional or noninstitutional, incumbents or oppositional actors, or a mix of those. The characteristics of the actors who drive the transition – elites, counter-elites, or a combination of the two – have in fact been singled out as having an impact on the development of the transition as well as on the next steps in democratization processes, with higher expectations for cases of transitions by rupture (Munck and Skalnik Leff Reference Munck and Leff1997).Footnote 2 While some scholars tend to consider mass mobilization as potentially dangerous in moments of transition, as it places a higher expectation on the emerging regime, others have suggested that pressures from below can instead improve the quality of life of affected citizens by bringing about deeper democracy (Anderson Reference Anderson2010), more gender equality (Viterna and Fallon Reference Viterna and Fallon2008), a more progressive welfare state, more effective land distribution and educational policies (Foran and Goodwin Reference Foran and Goodwin1993), and more efficient agrarian development (Bermeo Reference Bermeo1986). When transitions derive from pacts among elites that control the agenda on issues to be addressed, this might instead be expected to increase inequalities among the citizenry (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1984, 366). In fact, more inclusive coalitions of opponents are then expected to be more conducive to democracy, as they will exert pressure to accommodate a broad range of claims. In this direction, it has been concluded that “transitions from below have better chances of installing a new government which has fewer nondemocratic elements because fewer, if any, promises have to be made to the authoritarian regime to get it to exit, allowing the new democracy more leeway to introduce reform” (Casper and Taylor Reference Casper and Taylor1996, 10).

Particularly relevant for the analysis of the effects of paths of transition on democratic qualities is Robert Fishman’s comparative work on the Iberian Peninsula. Considering the role of civil society in democratization, he suggested that paths of transition have an effect on whether predominant forms of democratic action incorporate the voices of low-income and socially marginal sectors. In particular, pathways into democracy are expected to hold enduring consequences, as “the legacies of democratization scenarios take the form not of fixed states but instead of ongoing approaches to a wide range of political matters. Regime transitions hold the ability to change not only the basic rules linking governmental institutions to the broader populace, but also a variety of social practices and understandings” (Fishman Reference Fishman2011, 4). Civil society and the emerging regimes “are mutually constitutive, developing in a dynamic and iterative series of interactions” (Fishman Reference Fishman2013, 3), as the “forms taken by civil society and its action in the context of democratic transition carry large and enduring consequences for the type of democratic practices that dominate after transitions” (ibid., 4).

Building upon these theoretical and empirical suggestions, I expect the role of social movements in transition to be reflected in their post-transition relations with the state, with more recognition of civil, political, and social rights in regimes that emerge from eventful democratization rather than participated pacts. My assumption is that if participated pacts are based on compromise within elites, eventful democratizations should instead leave more space for in-depth, unconstrained transformation. In fact, despite the relative brevity of those periods, “Decisions made during revolutionary moments about future institutions can structure political competition in the short to medium term by defining who is permitted to participate in the polity and on what terms” (Glenn Reference Glenn2001, 11). The mentioned path-breaking research on the Iberian Peninsula, based on a comparison of Spain as a case of participated pact and Portugal as a case of eventful democratization, has shown indeed how the path of transition influences the interactions between power holders and protestors in the ensuing regime – particularly with regard to democratic practice, defined as “the way in which actors within a democracy understand and make use of opportunities for political action and influence, and interact with other participants in the polity” (Fishman Reference Fishman2013, 5). This refers not only to emerging institutions but also to implicit cultures that define shared norms; so action affects the recognition of civil society voices, beyond their strength and resources. As Fishman noted, cultural processes working in times of flux have an impact on practices by reconfiguring fundamental elements of national identities and the public rituals that affirm them.

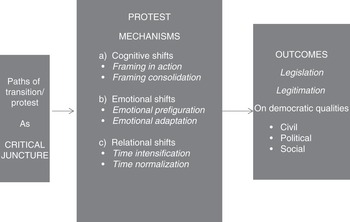

Considering the theoretical and empirical literature, we can therefore expect that paths of transition might influence the consolidation phase through mechanisms of legislation, that is, through the making of law and regulations, particularly on the issues that are central for the movements, as well as legitimation, as the recognition of some actors and forms of action. These mechanisms affect civil, political, and social rights.

As we will see in what follows, Czechoslovakia as a case of eventful democratization and Poland as a case of participated pacts tend to confirm the trend that emerged in the Iberian Peninsula. However, by extending the number of cases beyond a binary comparison, I can not only control the robustness of the results of previous studies but also expand and complexify our theorization on the effects of social movements’ participation in transition phases by looking at potentially disturbing factors in the moments of installation and consolidation. In particular, I will suggest two specifications.

First of all, it will emerge (in particular through a comparison of Czechoslovakia and the GDR) that besides the strength of the social movements and of the mobilization from below, external factors can intervene during the installation phase that thwart the movements’ capacity to affect consolidation. Modes of installation differ, in fact, in terms of duration and the constellation of the civil (and sometimes military) actors that participate in them as well as in the degree of inclusiveness and the forms of conflicts involved.

Second, as the extension of case studies from CEE to the MENA region will make clear, considering mobilizations for democracy as critical junctures does not imply the expectation that movements’ victories are either straightforward or durable. As research on revolutions has pointed out, the battles between revolutionary and counterrevolutionary, new and old elites, moderates and radicals last well beyond highly symbolic moments of change. While social movements might continue to be important actors in democratic installation and initial phases of democratic consolidation, empowered by their successes, their adversaries often reorganize to reduce the amount or reverse the direction of the social and political changes. Critical junctures transform some things, but they do not change everything, and they are not irreversible. To be sure, I do not suggest that the transitional critical juncture determines once and forever the quality of democracies but rather aim to trace back and discuss some of these effects in terms of citizens’ rights and social movements as well as civil society characteristics. I will argue, however, that power relations within and outside movements, even if reshuffled, nevertheless continue to affect postrevolutionary process.

In order to understand these complex developments, we need in fact to look in-depth at the evolution of the waves of protests that, I suggest, accompany eventful democratization. Besides expecting a tide of contention that advances, peaks, and retreats, I look inside protests in order to trace the ways in which cognitive, affective, and relational mechanisms evolve along the waves of contention, seeing them as a necessary step in order to understand their effects. While I consider democratic qualities as explananda, I do not aim at a complete assessment of civil, political, and social rights, or at identifying all possible causes for them. My purpose is rather to link some specific democratic qualities to social movements’ participation in the paths of transition. In this sense, using the language of Mahoney and Goertz (Reference Mahoney and Goertz2006), I will not pretend to provide a complete causal explanation of democratic qualities (by identifying the causes of an effect) but rather investigate the effects of some specific mechanisms – singled out in each chapter – that I see as being at work in the evolution of the various processes of democratization I address.

Causal preconditions might indeed not be the most pertinent questions to address phenomena that develop in time, interacting with different structural conditions and changing structures. This is why, in my cross-national comparison, I am not interested in discovering general laws and invariant causes that could explain all the cases at hand. Rather, I want to identify some dynamics that are present in the evolution of these different cases. In this sense, I have built upon a research design that allows me to move beyond the analyses that trace dissimilarities between similar types, and look instead for similarities in the causal mechanisms through which different types of democratization unfolded (see also McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001).

In recent years, the language of mechanisms has become fashionable in the social sciences, signaling dissatisfaction with correlational analysis (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2003). The concept of the causal mechanism has been used, however, in different ways: to refer to (historical) paths, with a search for events that are observable and context dependent; or to address micro-level explanations, with a search for variables at the individual level. In macro-analyses, causal mechanisms have been linked to systematic process tracing through a causal reconstruction that “seeks to explain a given social phenomenon – a given event, structure or development – by identifying the process through which it is generated” (Mayntz Reference Mayntz2004, 238). In micro-level explanations, instead, the theoretical focus is on “detailing mechanisms through which social facts are brought about, and these mechanisms invariably refer to individuals’ actions and the relations that link actors to one another” (Hedstrom and Bearman Reference Hedstrom, Bearman, Hedstrom and Bearman2009, 4). In my own understanding, mechanisms are categories of sequences of action that filter structural conditions and produce effects (see della Porta Reference della Porta2013b, Reference della Porta2014a). Following Tilly (Reference Tilly2001), I conceptualize mechanisms as relatively abstract patterns of action that can travel from one episode to the next, explaining how a cause creates a consequence in a given context. I would not restrict capacity of action to individuals, however, instead including collective actors as well. Adapting Renate Mayntz’s (Reference Mayntz2004, 241) definition, mechanisms are considered in my research as a concatenation of generative events linking macro causes (such cycles of protest) to aggregated effects (such as democratic qualities) through the relations between individual and organizational agents.

The focus on causal mechanisms has been connected with the so-called processual turn in social movement studies, which in fact shifted attention from static variables to the processes connecting them (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001). In a similar vein, in my work on political violence (della Porta Reference della Porta2013b) and on democratization from below (della Porta Reference della Porta2014a), I suggested an approach that is, first, relational, as it considers social movements within broader fields that see the interactions of various actors, institutional and noninstitutional. Second, the approach is constructivist, as it takes into account not only the external opportunities and constraints but also (and especially) the social construction of reality by the various actors participating in social and political conflicts. Third, the approach is dynamic, as it recognizes that social movement characteristics develop in intense moments of action and aims at reconstructing the causal mechanisms through which conflicts develop.

I will in particular address cognitive, affective, and relational mechanisms. At the cognitive level, protest cycles involve a mechanism of framing in action as, especially in the ascending phase of the protest and at its peak, some visions of participatory and deliberative democracy develop. Notwithstanding contextual changes, there are then mechanisms of framing consolidation that also sustain those visions during the low ebb of the protest, contributing to disengagement from institutional forms of participation.

Cognitive mechanisms are accompanied by emotional ones, with a transformation in the dominant emotional climate. As protest grows, mechanisms of emotional prefiguration, as emotional work oriented to control fear and engender empowerment, develop in action. In the declining phase, mechanisms of emotional adaptation accompany a general mode of disillusionment, which however does not cancel the experience of empowerment.

Finally, I will look at the relational resources produced in intense time, as well as the shift in normalized time. During the emergence and growth of protest activities, both individual and organizational ties increase at high speed through a mechanism of time intensification. Protest decline is then reflected in a reconsolidation of the net of interactions (and expectations), through mechanisms of time normalization.

In particular, I expect that in the eventful path of transition, horizontal conceptions of democracy are supported “in action,” hope is fueled by clear victories, and time is perceived as moving at a particularly intense pace (see Figure 1.1). While cognitive visions, emotional feelings, and relational expectations change at the end of the eventful democratization, I expect that the democratic framing developed in action, the feeling of empowerment, and the impressions of intense time will remain relevant experiences for those who lived them.

Figure 1.1 From Critical Junctures to Outcomes: The Theoretical Model

The interactions of relational, emotional, and cognitive mechanisms bring about an increased capacity to affect the institutional process in a moment of opening opportunities, as well as establishing a more inclusive culture. While this does not automatically translate into more protests, it does create more favorable conditions for the development of civic, political, and social rights. Once again, however, these effects are filtered through specific interactions among different actors.

The Research Design

The research is based on a comparative analysis of cases of eventful democratization versus participated pact, as defined earlier. In order to understand the effects of paths of democratization on the development of social movements and on some democratic qualities, I will first compare four countries in CEE: Czechoslovakia (and then the Czech Republic) and the GDR as cases of eventful democratization, on the one hand, and Poland and Hungary as cases of participated pacts, on the other. Within a most-similar research design, the aim is to single out robust mechanisms that distinguish the two paths. However, the two-plus-two comparison will also allow the identification of some infra-path dissimilarities and therefore the specification of causal mechanisms that intervene between transition and consolidation.

In the second part of the research, I will then perform a partial comparison between 1989 in CEE and 2011 in the Arab Spring, by replicating some of the research in Egypt and Tunisia. Through the analysis of these cases, I aim at “complexifying” my line of analysis by showing that, while some mechanisms are similar in 1989 and 2011, different conditions of installation intervene in transforming the type of processes after transition. While in both cases the outcomes of the democratization paths are still unclear, with more optimism for Tunisia than for Egypt, some information on the years immediately following the episodes of democratization in 2011 will allow further discussion of the mechanisms of demobilization of social movements after regime change, as well as on the effects of the mobilization for democracy on the further evolution of democratization processes. Besides controlling the robustness of some results of the empirical analysis of the 1989 transitions through a cross-time as well as cross-area comparative design, this further comparative element will allow some reflections within cases of eventful (episodes of) democratization that had different outcomes in terms of consolidation.

As it is often (and increasingly) the case in comparative politics (Schmitter Reference Schmitter2009), we cannot assume that countries as units of analysis are independent from each other. This is all the more the case in waves of democratization during which the involved countries are intensively related to each other, with frequent learning by both the movements and the regime (e.g., Beissinger Reference Beissinger2007; Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce, Wolchik, Givan, Roberts and Soule2010). Rather than assuming independence of countries, I recognize the cross-national influences, addressing them during the analysis.

All in all, I do not aim at theory testing but rather at theory building, within a logic of discovery that I think is appropriate to the state of knowledge in the field and the aims of my research. Keeping an interest in the historical events that I analyze, I compare by cases rather than by variables, through an in-depth analysis of complex systems of relations that cannot be fragmented into their main components (della Porta Reference della Porta, della Porta and Keating2008). While using secondary literature as well as documentary sources to reconstruct some aspects of the democratization process, given the already mentioned importance I give to the construction of the external reality, the research considers as most relevant the activists’ perceptions of the historical events of which they have been part.

These preferences and choices are reflected in the methods used in the empirical research for data collection and data analysis.

Protest Event Analysis

From the methodological point of view, part of the research is based on protest event analysis as a way to single out some main characteristics of contentious politics in the period of transition as well as in the ensuing years. Using existing databases, but recoding the data when necessary, attention focuses first on three years including transition in Poland, Hungary, GDR, and Czechoslovakia, also adding Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania. Moreover, in order to be able to investigate long-term developments in more depth, I used the Prodact database on protest in Germany within a comparison of the eastern and western regions in the country. Post-reunification Germany offers an experimental setting in which to note both the adaptation to protest waves in established democracies and the resilience of democratization politics. In particular, the comparison of the former Federal Republic of Germany in the west and the former German Democratic Republic in the east can be particularly telling, allowing for the observation of cross-regional similarities and differences in terms of the amount, aims, and forms of protest. Similar original data are presented for Egypt and Tunisia.

Protest event analysis is a much-used quantitative methodology to study the dynamics of protest in time and space. First employed by Charles Tilly and his colleagues during the 1970s to shed light on the historical transformations in repertoires of collective action, it later inspired other important studies on the American civil rights movement (McAdam Reference McAdam1982), the Italian cycle of protest during the 1970s (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1989), new social movements in Western Europe (Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak, and Giugni Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1995), and the transformations of environmental activism in Europe (Rootes Reference Rootes2003). As synthesized by Koopmans and Rucht, protest event analysis “is a method that allows for the quantification of many properties of protest, such as frequency, timing and duration, location, claims, size, forms, carriers, and targets, as well as immediate consequences and reactions (e.g., police intervention, damage, counter protests)” (Reference Koopmans, Rucht, Klandermans and Staggenborg2002, 231). In general, daily press represents the source for the analysis, where articles on protest are found and coded following specific methods of content analysis (Lindekilde Reference Lindekilde and della Porta2014) with a focus on protest (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1995; Hutter Reference Hutter and della Porta2014). In this process, the primary unit of analysis is the protest event, and information is collected on indicators that usually include the actors who protest, the forms they use to protest, their claims, and their targets (as well as place, time, and immediate outcome).

While extremely helpful in defining broad trends in protest, protest event analysis must be handled with care (Hutter Reference Hutter and della Porta2014). In fact, the reporting of protests is quite selective, and selectivity is often a source of bias, as the portion of the universe of protest events that is reported is never a representative (nor a random) sample but rather – pour cause – influenced by the logic of the media. This affects tendentially all main dimensions of the analysis, as we can expect that some actors (either more endowed with institutional resources of access to media or more “scandalous” per se), forms of action (those involving more people, more violence, or more innovation), and issues (those with high news value within specific issue cycles) are more likely to be reported (McCarthy, McPhail, and Smith Reference McCarthy, McPhail and Smith1996; Fillieule and Jimenez Reference Fillieule, Jiménez and Rootes2003; Hutter Reference Hutter and della Porta2014). Reporting can also be more or less detailed and neutral according to the characteristics of the actors and forms of actions. Additionally, the more frequent the protest becomes, the more selective will necessarily be its reporting.

In addressing these biases, two observations have to be taken into account. First, we can assume that as protest is an act of communication, protest event analysis captures those events that have already overcome an initial important threshold to influence public opinion and policymakers: being reported upon (Rucht and Ohlemacher Reference Rucht, Ohlemacher, Eyerman and Diani1992). In this sense, Biggs (Reference Biggs2014) suggested a focus on large events, which are both covered in a more reliable way and analytically important. A second caveat is that, as for any source, we need to be self-reflexive, acknowledging and considering bias when interpreting the results as well as triangulating newspaper-based protest event analysis with reporting of protests in other sources.

For this research, data on Eastern European countries shortly before, during, and after transition come from the European Protest and Coercion 1980–1995 Database,Footnote 3 covering twenty-eight countries in Europe. Based on news reports on domestic conflicts, it comprises all reported protests and repressive events for which a date and a location could be identified. Data were coded for each day/event, by one expert coder per country. The primary source of the data base was LexisNexis, accessed through Reuters textline library, which provides access to over 400 wire services and online newspapers and magazines, choosing the highest quality sources in case of divergent reports.

For part of the research on Germany, I used the Prodat dataset that emerged from the research project Dokumentation und Analyse von Protestereignissen in der Bundesrepublik. Protest events were extracted from the coverage of two high-quality newspapers (Frankfurter Rundschau and Süddeutsche Zeitung) from 1950 to 2002. It is important to note that only a sample of the coverage was searched and coded, namely every Monday’s edition plus Tuesday through Saturday every fourth week. Thus, the database does not report all protest events to be found in both papers, but only those reported in the selected issues. For the comparison between East Germany and West Germany, the data subset includes only protests taking place in the territory of eastern and western Länder, respectively. Cases of protests in Berlin (where it would be difficult to distinguish between protest in the East and the West) and nationwide protests are excluded from the analysis or presented separately.

For Egypt and Tunisia, we relied mainly on LexisNexis as much as possible using similar strategies to the ones developed for the CEE countries. For Tunisia, in the first stage, we opted for “search for content type” and then clicked on “newspapers” in advanced options to determine the source type. Then, we entered “protest! OR strike! OR demonstration! w/25 protest!”Footnote 4 into the search engine, and sorted the news by date (from oldest to newest for each month in each year). As a second step, we asked LexisNexis to browse news only from the following sources with reasonably high coverage for international audiences: BBC Monitoring International, Agence France Press, Associated Press, Agency Tunis Afrique Press, and Xinhua. The resulting articles were then coded. For both Tunisia and Egypt, we also utilized supplementary material from the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT) and the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS). Created by Kalev Leetaru from Georgetown University, GDELT is a project that brings together online records of social and political events since 1979 from a variety of news sources around the globe, such as Agence France Press, BBC Monitoring, and the New York Times. It transforms them into a computable format, and is automatically updated every fifteen minutes (Leetaru and Schrodt Reference Leetaru and Schrodt2013). The GDELT Event collectionFootnote 5 contains more than 250,000 records (originally retrieved from LexisNexis) covering three decades of political events (from January 1, 1979, to the present) coded across fifty-nine variables. For this study, we query the entire GDELT database, pairing Google BigQuery cloud-based analytical service and the statistical analysis software Tableau, and extract the subsets deemed relevant for the analysis. The most used variables are: “ActionGeo” (location of the event), “Event Code” (type of event), “Actor1*” (type and country affiliation of the initiator of the action), “Actor2*” (type and country affiliation of the target of the action), and “Quad Class” (an aggregation of the CAMEO event codes into four categories ranging from Verbal Cooperation to Material Cooperation, Verbal Conflict, and Material Conflict).Footnote 6

For the protest event analyses, the codebook included the following core variables: date, form of action, target, issue, number of protestors, and number of persons arrested/injured/killed.

Oral History

Protest events data are triangulated with in-depth interviews with activists of the movements for democracy in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, GDR, Poland, Egypt, and Tunisia. In the study of activism, historians have long experience with oral history, used either to collect information on events or groups for which archives are particularly poor or as materials for the study of mentalities and culture. In both types of contribution, individual activists are considered as central sources for their capacity to act beyond existing external constraints (Balan and Jelin Reference Balan and Jeilin1980), as “attention shifts from laws, statistics, administrators and governments, to people” (Thompson Reference Thompson1978, 223). Against a vision of history as created by the elites, oral history places normal people as important actors in the making of history (Barkin Reference Barkin1976; Bertaux Reference Bertaux1980; Buhle Reference Buhle1981; Passerini Reference Passerini1981). By giving normal people a voice, and thus going beyond official documents, “these studies emphasize the importance of understanding the way in which history is transformed in individual cognition, how public events intervene into private life, how perceptions of the world influence action” (della Porta Reference della Porta, Diani and Eyerman1992, 173). The use of oral sources thus responds to “the need to analyse every aspect of everyday life to restore sense to activities that seem to be losing it, sucked out by current, alienated uses” (Passerini Reference Passerini and Passerini1978, XXXVII). In this conception, normal people play a vital role in giving history sense, direction, and an ultimate goal (Buhle Reference Buhle1981, 209).

In social movement studies, oral history has been considered as particularly suited “for researchers interested in generating rich and textured detail about social processes, understanding the intersection between personal narratives and social structures, and focusing on individual agency and social context” (Corrigall-Brown and Ho Reference Corrigall-Brown, Ho, Snow, della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013, 678). The narratives of the events convey contextual information (Reed Reference Reed2004, 663) but, what is more, the stories people tell about their personal experiences reveal how subjective meanings are attached to the unfolding of eventful protest.

As with protest event analysis, the researcher must be aware of the potential bias of this type of source as well. Concerns have been expressed, in fact, about their reliability, as individuals are said to be the worst narrators of events in which they have been involved, insofar as they have a direct interest in them. Memory implies creative acts of imagination; the truth is often manipulated through narrative ability; people also tend to forget, confound, and lie. Literary ambitions or economic interests are seen as incentives to present one’s own life as more dramatic and one’s own role as more influential (Faris Reference Faris1980; for a summary, della Porta Reference della Porta and della Porta2014b).