In 1994, Tetlock (Reference Tetlock1994, 510) argued that social science had the potential to be driven by ideological as opposed to value-neutral considerations, resulting in a disciplinary “hell” where “[w]e discover that our powers of persuasion are limited to those who were already predisposed to agree with us (or when our claims to expertise are granted only by people who share our moral-political outlook).” At the time, his warning was met largely with disinterest or dismissal. It now seems prescient. Since 2015, the Pew Research Center has detected a sharp decline in the proportion of Republicans who believe that colleges and universities have a “positive effect” on the country; by 2017, a clear majority believed institutions of higher education exerted the opposite and negative effect (Fingerhut Reference Fingerhut2017). In 2017, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court called data presented in a gerrymandering case “sociological gobbledy-gook.”Footnote 1 The result is that Republican lawmakers have taken a more aggressive stance toward higher education, including the regulation of faculty-hiring practices, the linking of public funding to free-speech policies, and efforts to emaciate liberal arts education in favor of a university that focuses on skills.Footnote 2

We might easily reject this response as exaggerated or misplaced. As social scientists, however, it is important to consider carefully any role we play in stoking anti-intellectualism and distrust of the academy and research. For example, in the Pew surveys, both Republicans and Democrats viewed a college education as useful and held similar attitudes about the high cost of college. Observers, therefore, cite the increased liberal homogeneity of college professors and accompanying and intensifying media coverage as the most likely explanation for such a radical change in Republican views (Turnage Reference Turnage2017).

Research suggests that the professoriate is highly skewed toward Democratic and liberal views and that this has increased substantially over time. A comprehensive study of the academy in the early 1970s revealed it to be “divided” politically, with fewer than a majority of college professors characterized ideologically as liberal and almost a third as conservative (Ladd and Lipset Reference Ladd and Martin Lipset1975). More recent studies reveal that Republican identification has declined substantially with less than 20% self-identifying as conservative or Republican—a percentage that diminishes to about 5% among social scientists and humanists (Gross and Simmons Reference Gross, Simmons, Gross and Simmons2014).

It is important that we examine ourselves and consider the implications of a political science discipline that is politically and ideologically more unified than diversified. We engage in this effort with great intellectual humility and, as a liberal Democrat and a conservative Republican, our goal is not to point fingers but rather to raise an important question. We serve an ideologically heterogeneous society. Do we do that well if there are few conservatives within our ranks?

WHY PARTY AND IDEOLOGY MIGHT MATTER AND WHY WE SHOULD CARE

First and foremost, we are human beings—only secondarily are we political scientists. As individuals, we likely suffer from the same psychological proclivities that explain the political polarization of those we study, including prejudicial reasoning, confirmation bias, sorting, and groupthink. Although the point of science is to curb predispositions by disciplining our mind and using evidence to determine truth, the fact is—at least residually—that our biases remain.

Although the point of science is to curb predispositions by disciplining our mind and using evidence to determine truth, the fact is—at least residually—that our biases remain.

Perhaps the most important theory to consider is motivated reasoning, which is especially prominent in the political realm. It asserts that people have an unconscious tendency to process information to achieve a particular conclusion that is consistent with previously formed attitudes (Kunda Reference Kunda1990). Simply stated, the preference motivates the cognition. The mechanisms underlying the cognition also are important and include prejudicial information searches, biased assimilation, and identity-protective cognition—all of which involve searching for evidence consistent with and dismissing evidence inconsistent with an investigator’s worldview. As individuals, we routinely engage in motivated reasoning; as scientists, we must understand this phenomenon and how it can influence our work. Judicial scholars, for example, show that the ideology of judges and other legal actors influences decision making. How can we conclude that such factors are not motivations in our own work?

Second, we should consider sorting. It is likely that sorting occurs in the professions. It would be unsurprising to find that police officers might be both more conservative and authoritarian, and it is conventional wisdom that Hollywood is liberal. The effect of sorting, as one side becomes increasingly dominant, is that outgroup members leave or simply are silenced, reducing their numbers and influence. Inbar and Lammers (Reference Inbar and Lammers2012) and Honeycutt and Freberg (Reference Honeycutt and Freberg2017) found that conservative professors indicate they are more likely to face a hostile climate and are less willing to share their views, although they are no less happy (Abrams Reference Abrams2017). Furthermore, although Honeycutt and Freberg (Reference Honeycutt and Freberg2017) showed that both liberals and conservatives are about equally more willing to discriminate against a paper, grant proposal, speaker, or job candidate that they believe to be of the opposite ideology, there are few conservatives in the discipline to counteract collective liberal bias. This may explain the long-term trend toward greater ideological uniformity in the university. It also is consistent with research in political science showing that out-party members are discriminated against on a host of nonpolitical judgments and behaviors—including employment—substantially exceeding effects explained even by race (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2014).

Third, motivated reasoning and sorting can result in groupthink, a process that leads group members to minimize conflict, suppress alternative viewpoints, and encourage the self-censorship of deviant ideas. Where there is high group cohesiveness, there is increased risk of groupthink. Research into confirmation bias, a related phenomenon, shows that scientists are more lenient with methods and research designs when the conclusions are consistent with their ideological beliefs (Ceci, Peters, and Plotkin Reference Ceci, Peters and Plotkin1985). Importantly, confirmation bias is even stronger when questions are raised about morality and identity—topics central to politics and political science (Haidt Reference Haidt2012).

Political scientists also have made themselves fair game for analysis. Many of us have spent considerable time persuading students, colleagues, readers, reviewers, reporters, and the public that the political behavior of a particular narrow segment of the general population is worthy of study. If we believe that political ideology matters for specific occupational and demographic groups, it most certainly should matter for us as well.

Finally, many political scientists have written about the value of descriptive representation to feelings of legitimacy, empowerment, and fairness. It seems that a lack of political diversity should be a “red flag” to problems of inclusion and representation, especially when roughly 40% of American adults indicate that they are conservative.

DATA AND METHODS

We relied on administrative data to explore our question about the partisanship and therefore ideology of political scientists. Partisanship is a proxy for political ideology, especially among the well informed. We focused on two states, Florida and North Carolina, as a preliminary study of partisanship in political science because we did not have access to a national voter file or sample frame. We chose these states for various reasons, including the fact that they make their files easily accessible and free to academics. Both states are “purple” with a diverse electorate (i.e., 37% Democratic, 35% Republican in Florida; 39% Democratic, 30% Republican in North Carolina). Given the competitive nature of the two states, identifying as a Republican may be less problematic for political scientists. This suggests that if we are biasing our results, it would be toward overestimating the number of Republicans in any national imputation.

To create our sample frame, we gathered information about professors from departmental websites, which provided information on faculty members’ rank and professional interests. We ascertained attributes such as race, gender, and age from information including names, photographs, vitae, and personal knowledge of an individual. We used these data—as well as county of residence, date of hire, middle name, and precise residential address—to confirm the identity of professors in the voter-registration databases. We collected data on 612 tenured and tenure-track political science professors in Florida (259) and North Carolina (353), of whom 500 were registered to vote. We excluded adjuncts and instructors in non-tenure-track positions because they frequently are not reported on departmental websites. In most of the 112 cases for which we could not find data, it was because an individual clearly was not registered; there often was evidence that unregistered faculty had recently moved or were ineligible to vote because of their citizenship.

RESULTS

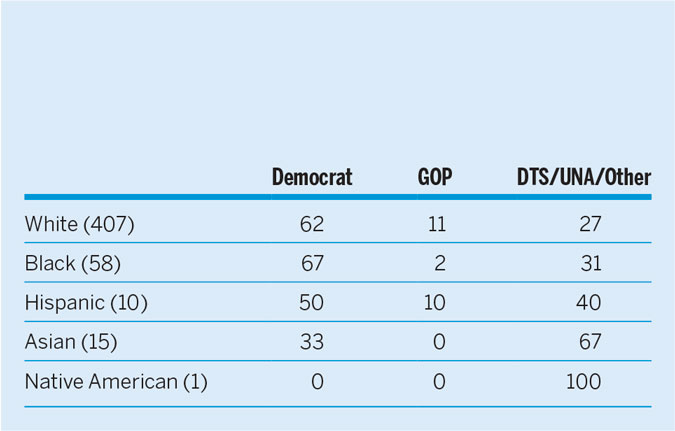

As table 1 demonstrates, the basic distribution by party registration confirms a significant skew toward Democrats in both states. Whereas 37% of Florida residents are Democrats, 63% of the state’s political scientists are. In Florida, 35% of residents are Republican; the percentage for political scientists is 13%. Similarly, 39% of North Carolinians and 60% of the state’s political scientists are Democrats, whereas 30% of residents are Republican but only 6% of political scientists are. In the entire sample, 62% of registered political science faculty are Democrats and about 9% are Republicans, a 6.9-to-1 ratio.Footnote 3

In the entire sample, 62% of registered political science faculty are Democrats and about 9% are Republicans, a 6.9-to-1 ratio.

Table 1 Percent Party Affiliation among Political Scientists and Residents in Florida and North Carolina

Approximately 29% of political scientists are independents: “did not state” (DNS) in Florida and “unaffiliated” (UNA) in North Carolina. This proportion is close to that of the states’ residents and probably more than many observers might expect. What explains the high percentage? Political scientists may want to hide evidence of personal political attitudes and behavior from public view to make more plausible claims about their neutrality in the classroom and public debate about politics and policy. Others with enhanced capacity and opportunities to influence political views and outcomes (e.g., judges and journalists) often explain that they do not vote or are independent; likewise, many political science faculty members can convey objectivity and neutrality by registering as independents.

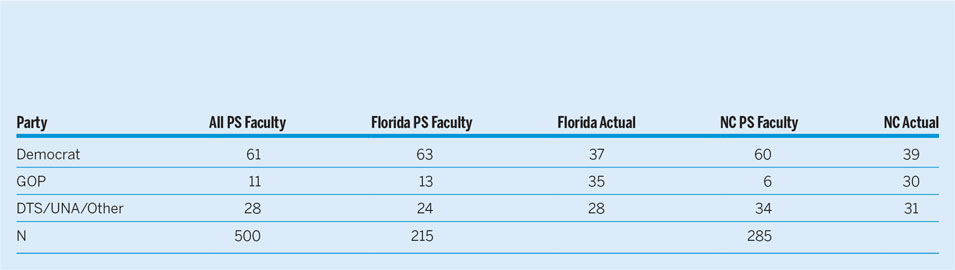

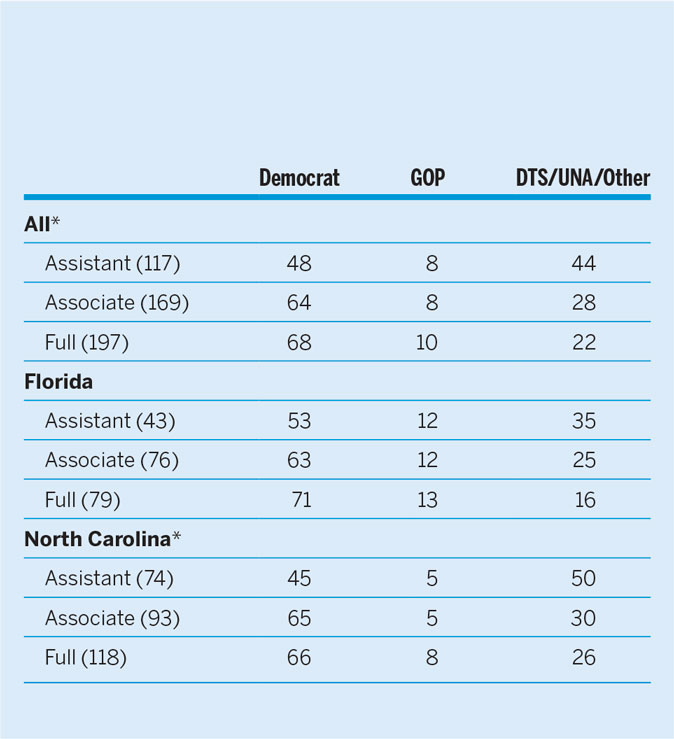

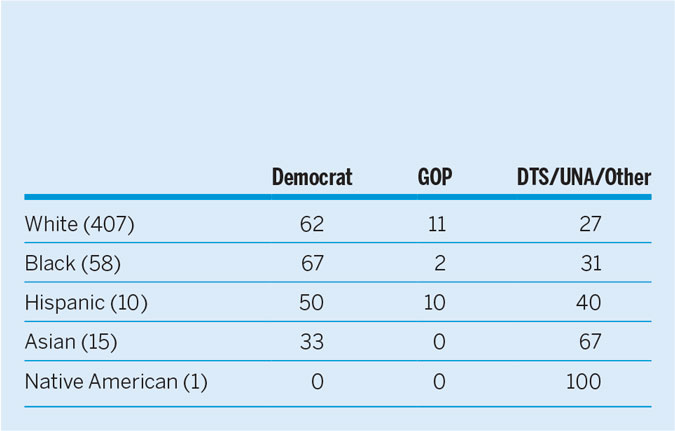

Tables 2 and 3 suggest the strategic nature of registering without a party. Table 2 categorizes respondents by rank and shows that senior faculty tend to be more partisan. This is consistent with national trends showing that younger people are more likely to register as an independent. Table 3 organizes subjects by race and ethnicity and reveals that whereas minorities are not more Republican than whites, they are much more likely to register as an independent. Of the 12 black professors who identified as independent, seven consistently voted Democratic and one was consistently mixed. In North Carolina, records of primary activity among UNA reveal that about 50% of assistant professors voted in each party’s primary, whereas 63% of associates and 86% of full professors voted in the Democratic primary. This suggests that the “true” proportion of North Carolina faculty identifying as Democrats is even higher than the percent reported in table 1. These data suggest that junior faculty perhaps feel a need or desire to hide their Republican leanings and African Americans their support for Democrats. Together, the findings point to faculty members who might feel less secure in their position, plausibly concealing personal political attitudes and behavior from students, parents, and other parties external to the university. These are unsettling interpretations.

Table 2 Percent Political Scientists’ Party Affiliation by Rank

Notes: *p<0.05, chi-square test.

Table 3 Percent Political Scientists’ Party Affiliation by Race/Ethnicity

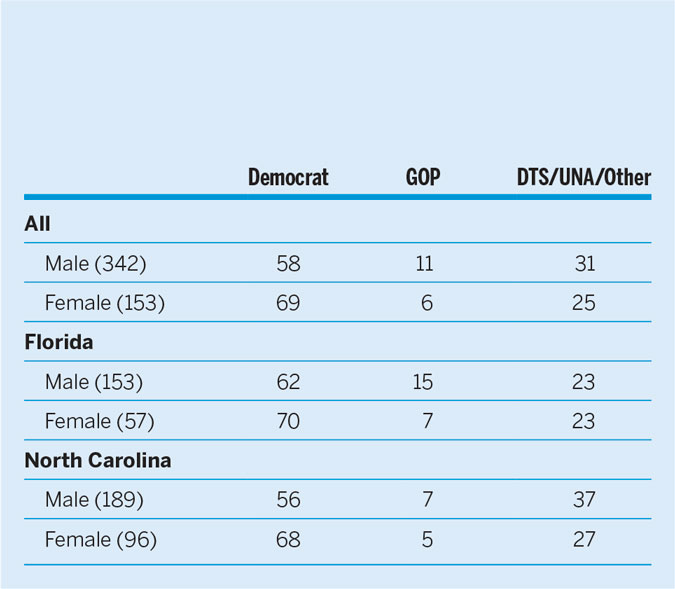

There also are perceptible distinctions by gender. Table 4 shows the breakdown of male and female registration. Like the general population, men were more Republican than women and vice versa. There are no statistically significant differences regarding field of expertise and whether an institution is private or public.

Table 4 Percent Political Scientists’ Party Affiliation by Gender

DISCUSSION

We found a disproportionate representation of Democrats among political scientists, which likely suggests a strong liberal bias. What are the potential implications of this bias? A nearly ideologically monolithic professoriate presumably prevents students from hearing diverse viewpoints as they learn about political, economic, social, and policy matters. In addition, political attitudes drive curricula interests among faculty who have significant freedom to design students’ courses of study. Homogeneity of views among professors likely narrows the realm of intellectual inquiry and debate.

Ideological dominance presumably influences research and scholarship. We have tremendous freedom to investigate matters in which we have interest and that have effects about which we care. Reviewers, editors, and editorial boards are likely to evaluate work with their own biases—not only in terms of methods used and conclusions reached but also subject matter covered. Disciplinary orthodoxy plausibly results in the rejection of work on unpopular subjects and with contradictory political viewpoints.

What are the potential implications of this bias? A nearly ideologically monolithic professoriate presumably prevents students from hearing diverse viewpoints as they learn about political, economic, social, and policy matters.

Compared to other occupations, college professors have tremendous power in the hiring, promotion, and retention of their colleagues. Existing research suggests that political scientists are likely to surround themselves with likeminded coworkers and those with whom they often have a previous association, reinforcing the homogeneity of political attitudes (Clauset, Arbesman, and Larremore Reference Clauset, Arbesman and Larremore2015).

More generally, we suggest that the state of affairs has internal and external consequences. Internally, the lack of diversity could hinder the pursuit of the truth. The lack of political diversity could (1) privilege liberal values and assumptions in the development of theory and method; (2) result in the concentration on topics that validate left-wing and progressive ideas, thereby reducing our level of knowledge; and (3) bias attitudes toward conservatives that negatively characterize their values, traits, and attributes (Duarte et al. Reference Duarte, Crawford, Stern, Haidt, Jussim and Tetlock2015).

Externally, we move into Tetlock’s “hell,” where the only people who believe us are those who initially agreed with us. We therefore risk being viewed less as scientists and truth seekers and more as taxpayer- and student-subsidized advocates who are mistrusted by substantial portions of the citizenry. Pew Research Center data clearly show that this is increasingly the case among conservatives; a 2018 survey of college presidents conducted by Inside Higher Ed supports this assertion (Lederman Reference Lederman2018). It is, to say the least, disconcerting.

CONCLUSION

Our convenience sample necessitates that this be an exploratory analysis. We believe political science needs a broad census. Our professional associations frequently conduct surveys and commission interpretive studies about race, gender, and other demographic attributes of their membership. They have the means to gather the data to undertake similar evaluations of political scientists’ political attitudes and behavior. Such a comprehensive study is key to the integrity and long-term health of our discipline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mark Rom and L.J Zigerell for their thoughtful comments. We are also grateful to Matthew Wilson, Josiah Marineau, Shawn Williams, and other participants in a roundtable on issues related to the paper held at the 2019 Southern Political Science Association meeting.