Introduction

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have implemented a range of strict public health measures to protect their populations against the spread of infection. Many of these measures have been directed at older adults (> 65 years), who are particularly vulnerable to severe COVID-19 infection (Béland & Marier, Reference Béland and Marier2020). In Ontario (Canada), a widely applied measure has been the implementation of visitor restrictions in institutional care settings, including long-term care homes, hospitals, assisted living facilities, and retirement homes (Hindmarch, McGhan, Flemons, & McCaughey, Reference Hindmarch, McGhan, Flemons and McCaughey2021). Beginning in March 2020, these restrictions prevented family and friend care partners as well as other visitors from entering these settings. Depending on the institution, there may have been exceptions, such as for those caring for a resident who was dying (Williams, Reference Williams2020). Further depending on the institution, restrictions persisted for months to more than a year, and have only been lessened with the distribution of vaccines.

Throughout the pandemic, there has been much public scrutiny over blanket visitor policies, because of their failure both to recognize the critical contributions of care partners in these settings, and to balance public health with other elements of resident well-being (Kemp, Reference Kemp2021; Stall et al., Reference Stall, Johnstone, McGeer, Dhuper, Dunning and Sinha2020). For example, research has shown that visitor restriction policies can cause undue harm to residents, families, and care staff (Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas, & Mayoral-Cleries, Reference Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas and Mayoral-Cleries2020; Hindmarch et al., Reference Hindmarch, McGhan, Flemons and McCaughey2021; Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al., Reference Sepúlveda-Loyola, Osadnik, Phu, Morita, Duque and Probst2020). Research following the SARS pandemic of 2002–2004 suggested that these types of restrictions contributed to increased distress, anxiety, fear, and frustration among families (McCleary, Munro, Jackson, & Mendelsohn, Reference McCleary, Munro, Jackson and Mendelsohn2006; Rogers, Reference Rogers2004). They also disrupted essential caregiving responsibilities and contributed to negative physical and emotional deterioration among long-term care residents (McCleary et al., Reference McCleary, Munro, Jackson and Mendelsohn2006). Emerging evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic echoes similar findings. Strict social distancing and isolation have been associated with increased loneliness, depression, anxiety, and sedentary behaviour (Goodman-Casanova et al., Reference Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas and Mayoral-Cleries2020; Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al., Reference Sepúlveda-Loyola, Osadnik, Phu, Morita, Duque and Probst2020). Visitor restrictions have also amplified the marginalization of family care partners and exacerbated existing communication challenges between care partners and care institutions (Hado & Friss Feinberg, Reference Hado and Friss Feinberg2020; Schulz & Eden, Reference Schulz and Eden2016).

Family care partners play a critical role in the maintenance of older adults’ physical and mental health and safety, yet visitor restrictions have prevented them from supporting the person they care for. Despite their essentiality, little research has been released to date on the experiences of family care partners who have been separated from their loved ones because of these public health measures. This study explores the perspectives of family or friend care partners on visitor restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and identifies their recommendations for creating more person- and family-centred public health policies.

Methods

We used a qualitative descriptive approach (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000) employing in-depth, semi-structured interviews with care partners. Unlike interpretive approaches that focus on the researcher interpreting the meaning of an event or phenomenon, qualitative description is concerned with knowing the who, what, and where of a phenomenon (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). For these reasons, qualitative description is particularly suited for research focused primarily on providing a detailed picture of individual experiences of an event (Babbie & Benaquisto, Reference Babbie and Benaquisto2010; Neuman, Reference Neuman2006). To develop a study approach that would examine the care partner experiences and perspectives in detail, we collaborated with older adult and care partner mentors throughout each stage of this research. These mentors had lived experience in this area and provided ongoing support and consultation to inform the work, including the development of data collection materials and plans for research dissemination.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Tri-Council Policy Statement for Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2) (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, 2018). Study procedures were reviewed and approved by Ontario Tech University’s Research Ethics Board.

Recruitment and Sample

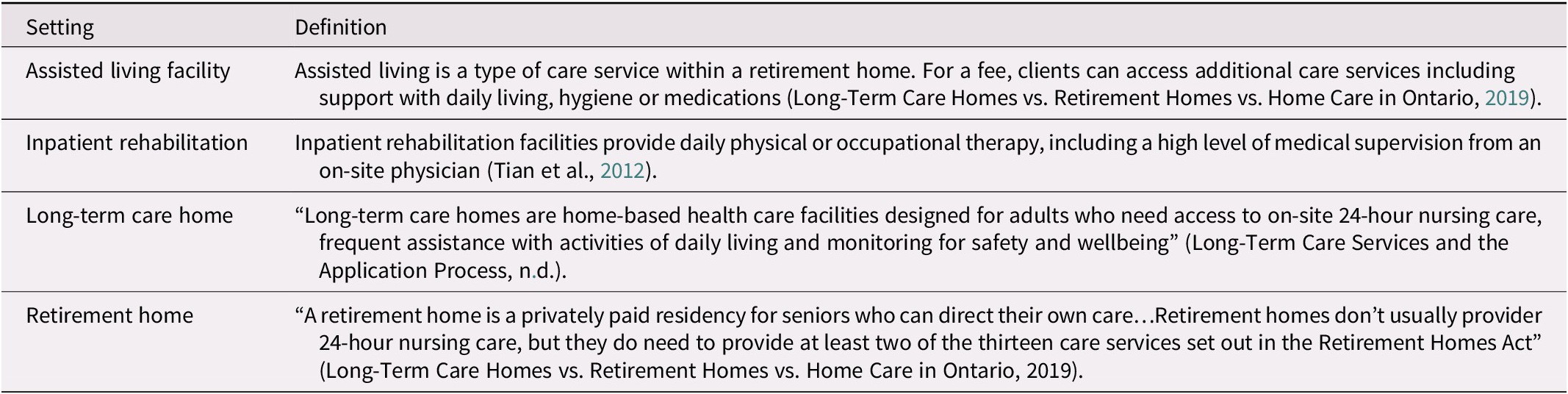

Care partners use different terms to describe their supporting and caring activities (e.g., care partner, informal care partner, caregiver, carer), or reject these labels altogether. We defined a care partner as any person who regularly provides some form of unpaid support (e.g., social stimulation, recreation, managing finances, or formal care, such as personal care, feeding) to an older adult friend or family member. To be included, care partners must have provided care to an older adult living in an institutional care setting in Ontario, such as a long-term care home, assisted living facility, or retirement community, at some point during the pandemic (Table 1 describes these settings). Additionally, care partners must have been impacted by visitor restrictions, such that they were not able to provide their usual care for any amount of time during the pandemic.

Table 1. Descriptions of the various care settings included in this research

Care partners are often connected with other care partners through social and formal support networks. For this reason, we used a combination of purposive sampling and snowball sampling to reach participants meeting the abovementioned criteria from across the province of Ontario. We worked with mentors and our professional networks to reach potential participants. Participants were recruited virtually using e-mail invitations and social media advertisements (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn). Interested individuals were invited to contact the primary investigator (P.I.) S.A.H. by e-mail or telephone. Participant eligibility was assessed prior to consent. When setting up the interview, the P.I. asked participants if they had used Zoom or other Web conferencing platforms before and if they were comfortable using Zoom. Most participants had experience and were comfortable using Zoom. For the three individuals who were uncomfortable or unfamiliar with Zoom, the P.I. provided basic instructions via e-mail. Informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews.

Data Collection

Qualitative interviewing – particularly semi-structured interviewing – is a method that enables a detailed understanding of individual experiences (Babbie & Benaquisto, Reference Babbie and Benaquisto2010). We encouraged a conversational style with the ability to ask in-the-moment questions, to provide participants with more control over the direction of the conversation and flexibility in how they responded to questions, which also assisted with building rapport and trust. To ensure that we met the study objectives, a semi-structured interview guide containing open-ended questions and probes was created and pilot tested. Questions focused on stimulating discussion about the care partner’s experiences in the context of institutional visitor restrictions, including understanding the role of the care partner prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of the visitor restrictions in their respective settings (including if and how they evolved over time), and the impacts of those restrictions on the older adult and the care partner. We ensured that all questions from the guide were addressed prior to finishing the interview. The final interview guide is available in Appendix 1.

Interviews were conducted in pairs, using Zoom, with one team member taking the lead conducting the interview, and a second monitoring the technology and taking detailed field notes. Interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes and were video and audio recorded and then transcribed. Each team member was responsible for independently listening and verifying the accuracy of each transcription, as well as removing all potentially identifiable information (e.g., names, locations). A second team member verified the quality of the final transcripts before data analysis.

A demographic questionnaire was created to help characterize the participants and the older adult(s) they supported. These data were collected prior to the interview.

Data Analysis

Upon consent, participants were assigned an alpha-numeric code with the preceding “C” (denoting care partner). All identifying information was removed from transcripts. Demographic and identifying information were stored separately. Demographic data were entered into a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) spreadsheet and descriptively analyzed. Analysis of interview transcripts and field notes was done using Elo and Kyngäs’ (Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008) inductive content analysis approach, including three phases: (1) open coding, (2) creating categories, and (3) abstraction. During open coding, each team member independently coded a set of assigned interview transcripts with field notes using a word processing program with tracked changes, highlighting, and comments features. A second team member then reviewed the data and initial codes. Research team members wrote analytic memoranda to assist with the later stages of analysis. Each pair discussed and finalized the coding of each participant’s data.

The categorization phase involved in-depth examination of the initial codes to create a description and organize the codes into larger themes based on relationships or similarities. Similar codes were merged or collapsed, and new codes were identified. Thematic visualization of the codes assisted in determining the categories. The final codebook was created once an initial thematic structure was agreed upon.

The abstraction phase involved all team members independently reviewing all data to examine any potential duplications or relationships between themes and codes. The team then met to discuss their observations and identify relationships among the themes. The team then discussed the findings in relation to the research question, and their potential significance.

Findings

In April and May 2021, we interviewed 14 care partners (11 females and 3 males) before reaching theoretical saturation. Care partners ranged in age from 50 to 89 years. Twelve participants provided care to a parent, four provided care to a spouse, and one provided care to a friend; six care partners provided care to more than one person. Most participants (n = 8) had been providing care for more than 10 years. Equal numbers of care partners provided care to a loved one residing in long-term care or retirement homes (n = 7 each), while two provided care to a loved one in assisted living, and one provided care to a loved one in an inpatient rehabilitative care setting. None of the care partners resided with the older adult whom they cared for.

We identified five themes during analysis: (1) changing public health and infection prevention and control (IPAC) policies, (2) shifting care partner roles resulting from visiting restrictions, (3) resident isolation and deterioration from the care partner perspective, (4) communication challenges, and (5) reflections on the impacts of visitor restrictions. Availability of resources to support care partners, and caregiving presented as an issue that operated among several of the identified themes, are therefore discussed in relation to relevant themes.

Changing IPAC policies

Care settings adopted different approaches to managing visitors throughout the pandemic. In some settings such as long-term care homes, specific recommendations were set to only allow “essential” visitors. Other care settings such as retirement homes and assisted living facilities were required to comply with relevant directives, which varied based on their statuses (e.g., government or private facility). Early in the pandemic, most institutions implemented similar policies, which included complete lockout of visitors and care partners. As such, many care partners were not permitted to visit the older adult they were supporting. Although many institutions ultimately adopted the idea of “essential care partners”, which typically encompassed one to two people who were most involved in an individual’s care, there was variation in how “essential” was defined and how policies were implemented across institutions. There were also exemptions in place for those visiting someone seriously ill or dying; however, there were also variations in how these exemptions were operationalized across institutions. One participant reflected on some critical challenges:

They did have palliative care exemptions almost the whole time…but it was only one or two [people] and most of us have bigger families and so how do you choose…I was talking to one woman who she could go in and one of her three children to say goodbye to their father…how do you choose that?…those are not choices families should have to make. (C22)

Participants described how policies evolved over time and varied depending on the institution. They described how facilities were tasked with interpreting continually changing and sometimes unclear government directives and public health guidelines, and how this resulted in variation in policies among providers, facilities, sectors, and regions within the province:

It seems as if every assisted living facility is writing their own rules, which sounds like a rather harsh way of saying it, but they have their own policies, guidelines that they’re following. (C11)

Policies and procedures such as temperature checks, face coverings, rapid tests, and visitation restrictions were adopted by most institutions; however, their execution varied from one place to the next. Care partners also talked about the different factors that prompted policy changes, such as learning more about the virus, increasing or decreasing local, regional, or institutional case counts, availability of tests, vaccines, and sudden events, such as resident deaths or outbreaks. Further, care partners explained how facilities struggled to balance the harms and benefits of changing restrictions while considering the repercussions for older adults and their care partners. Some participants acknowledged that the visitor restrictions were appropriate given the unknowns of the virus, and some praised them. For example, C20 attributed the fact that there had been no cases to the institution’s diligence with the restrictions: “They are so strict, they’re so good…it’s been [the] safest place for her to be.” However, the consequences of these policies were felt by all participants.

Shifting care partner roles resulting from visiting restrictions

Participants’ roles changed throughout the pandemic. Pre-pandemic roles differed based on the needs of the older adult(s) they were supporting and the institutions that these older adults were in. Some of the participants provided emotional support and encouragement, facilitated social connections, and ensured safety. Others described more formal, direct care roles, such as assisting with feeding, personal care, housekeeping, communication, mobility, physical activity, financial management, and health decision making. For many, their responsibilities had become a part of their daily routine, including supporting mealtime:

It was all part of my lifestyle, I guess, being his carer, being a part of my life and my family. So, they knew, my husband knew, that one night a week I was not home for supper, and I’d be with Dad. (C19)

With the introduction of visiting restrictions, most participants described how their roles were disrupted. With the exception of a few older adults who had access and the ability to independently use the telephone or a window to facilitate social connections with their care partner(s), many described being abruptly shut-out and being “turned away at the door” (C03), as causing distress: “I haven’t laid eyes on her apartment, her clothes, I have no idea about her personal care, I have nothing, and I am responsible for that” (C12).

Care partners consistently described their essential role in preventing or mitigating the effects of loneliness during the pandemic, and how restrictions prevented them from providing the care and support required to ensure the health, safety, and well-being of their loved one. They perceived there were insufficient staffing resources to fulfill these same roles. This prompted many to adapt their lives to maximize the support the older adult would have. Factors such as the care partner’s relative risk of exposure and transmission of COVID-19 (e.g., if they worked in a high-risk setting), physical proximity to the institution, and expertise or experience relative to the person’s needs, were all considered when adapting care partner roles to the changing restrictions.

The majority of participants described advocacy as a requisite function of caregiving. Several participants described how changing recognition of their care partner status strengthened their advocacy efforts into more formalized and collective approaches, including mobilizing others to advocate for shared priorities:

All of these people told me their stories and they wrote up their stories for me, and I wrote my story up…in a position statement. We then submitted it to policy and decision makers everywhere…our MPP, he called me, and he wrote a letter in support of what we had said and done. So, what that did for us, was [it] gave us a feeling of being less helpless. (C03)

Some participants described how they enacted their professional roles and used their knowledge, for example if they were a health care professional, to advocate more effectively. Participants described this advocacy as being an important factor in mitigating the isolation and consequential deterioration of the older adult they cared for.

Resident isolation and deterioration from the care partner perspective

Throughout the interviews, care partners expressed concerns about the physical and social isolation of their loved ones and the perceived subsequent rapid health declines. During the lockdown restrictions, older adults were confined to their institutions and oftentimes (at least initially), confined to their individual rooms. One care partner described the severe restrictions and isolation:

A couple of times they noticed on camera that we got too close – within six feet of her – and they put her in isolation for 14 days… that happened twice, and she just thought she was going to go out of her mind because she was just restricted to a room, and she wasn’t even allowed to look out her door because somebody would yell at her. (C19)

Although these restrictions were implemented to protect older adults vulnerable to the coronavirus, the extreme isolation was sometimes perceived to cause greater harm than the virus itself. Many care partners reported witnessing accelerated declines in physical mobility, cognition, and mental health. For example, care partners described their loved ones needing to use a wheelchair, falling more frequently, and experiencing a stroke. In the most significant cases, care partners attributed some deaths to the isolation resulting from visitor restrictions:

A lot of people that I knew had passed away, not because of COVID, because of collateral damage. They stopped eating – family used to feed every day. Nobody came in, they just stopped eating. (C08)

In addition to physical health deterioration, care partners perceived that older adults also experienced psychological effects. Rapid declines in mood, accelerated dementia, and increased apathy were described by care partners:

I’ve heard many people in homes have said, “I’d rather die than go through this.” This is horrible, and it really is that severe. Like the anxiety levels, the tuning out – lots of people have started to tune out and just blank out from their reality so their… the cognition is greatly reduced, their interest, their curiosity. (C22)

It was perceived that because they were physically isolated from their care partners, older adults in institutions often did not receive the same level of care that they had pre-pandemic. Lack of physical stimulation and decreased basic care were perceived to accelerate physical decline, while decreased social interaction and emotional support created new mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression.

Communication challenges

Participants identified communication as an important theme, describing various communication practices between the care institution and care partners. Some participants described strong institutional efforts to communicate with residents and families. As one participant stated: “every time there’s a new change, they send us an email and say, ‘this is what we’re doing, this is what you can expect’” (C20). Others, however, reported minimal communication from care institutions, and sometimes no communication at all.

Participants described concerns about transparency, particularly around outbreaks, deaths, and evolving visiting policies. Complicating these concerns were the methods of communication. For example, one care partner reported discovering an institution’s Facebook page where information had been posted for several months; however, they reported not being made aware of the page’s existence or of the intent to use it as the primary means of communication. Despite these barriers, several caregivers recognized the myriad challenges that care institutions were facing, and readily pointed out examples of effective communication when possible. C23, for example, remarked “I think they tried hard. But…initially, they didn’t know what they were dealing with.”

Because in-person visits were restricted, care institutions attempted to adapt communication strategies, including using window visits, scheduled telephone conversations, or technology such as FaceTime and Zoom. Care partners, almost universally, described these adaptations as limited and unsatisfactory, and identified significant barriers. For example, inclement weather, residents not living on the main floor, and windows that did not open were limiting factors for window visits.

Another common barrier was for residents with dementia or cognitive difficulties. One care partner (C03) stated that window visits did not work, because the person could not understand what the care partner was doing outside. They described similar challenges with virtual visits: “you can’t hold their interest; they look all around, and they hear you talking but they don’t really know where it’s coming from” (C03). Perhaps the most challenging aspect of technological adaptations were that they were simply not a replacement for in-person visits. As one care partner stated:

We’ve done a lot of experimenting with FaceTime and Zoom and my [loved one] doesn’t find all of that particularly satisfying. I mean it’s always assumed that technological interventions will fill the gap of the absence of family and social engagement…but if you’re going to depend on that and you’re not used to it, I think it’s just not a substitute. (C06)

Resources also challenged communication, with many care partners indicating that their loved ones required assistance for these alternate strategies and available assistance was, as one participant described, “sporadic at best” (C22). Lack of resources also impacted communication from staff to residents; for example, one care partner reported that because of their loved one’s decline in hearing, the easiest way to communicate was by writing notes; however, with staffing shortages this became an issue:

In the end we communicated by writing notes…he could answer us verbally, but it always took a while to read the notes. This was a challenge in the [facility] with the staff not…having time to write notes…so things would often go on unexplained. Or…something would happen, and [loved one] wouldn’t really understand because they just didn’t have the time to sit down and write notes and answer all those questions. (C19)

Reflections on the impacts of visitor restrictions

Throughout the interviews, care partners reflected on the impact that the pandemic had on themselves and their loved ones. They described vicarious trauma caused by being locked out of care institutions during periods when their loved ones’ health declined and as they neared the end-of-life. One care partner predicted the lasting effect that these restrictions might have:

The history of this trauma of not being able to cuddle the person you love who’s died will affect grieving for at least two generations of that family and the consequences are immense and we have no idea (C22).

Care partners felt that the pandemic highlighted the systemic devaluation of older adults in North America. They expressed that older adults were marginalized through societal views that they were all “at risk” and “vulnerable”. This led the care partners to reflect on their own future health needs with great concern. One care partner clearly described this feeling:

I mean there’s a lot of people my age right now looking at this, and they’re seeing their future, and then it scares the living daylights out of them. (C05)

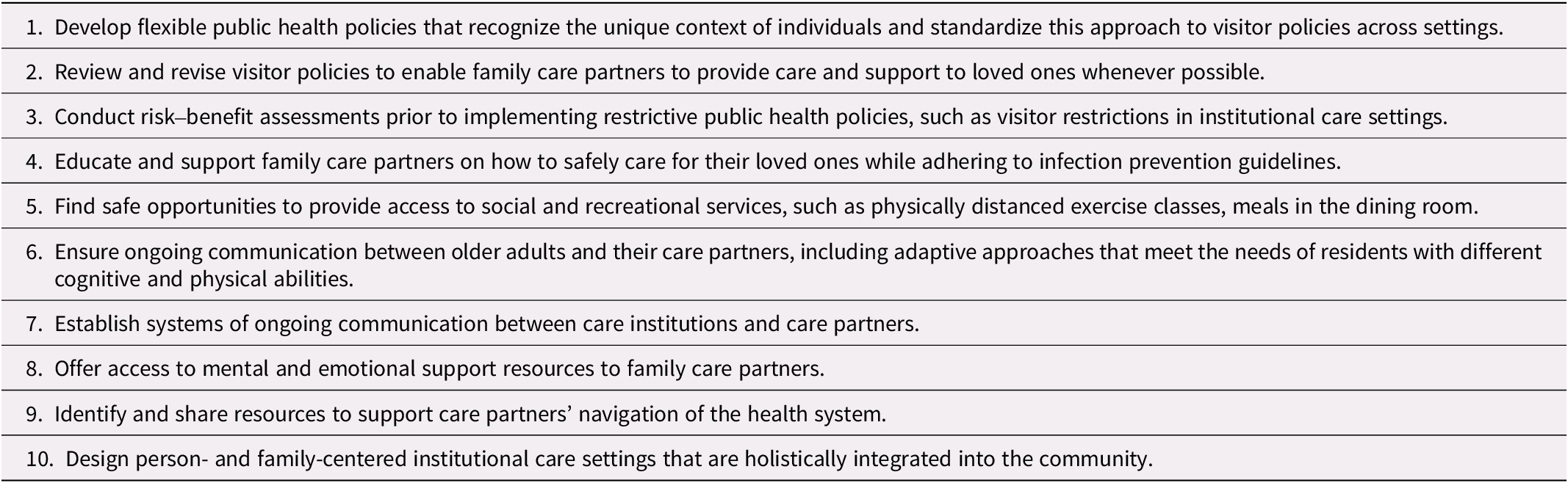

Several opportunities were identified, and participants provided recommendations to strengthen pandemic policies and practices in the future; these have been collated and summarized by our authorship team in Table 2. Most importantly, care partners emphasized the importance of limiting lockdowns in care institutions and ensuring flexible visitor access.

Table 2. Participant recommendations for care institutions

Discussion

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government of Ontario implemented strict restrictions for visitor and care partner entry (except in the cases of residents at the end of life) into institutional living settings, such as long-term care, retirement homes, and assisted living facilities (Government of Ontario, 2020). Similar restrictions were implemented across Canada and indeed, the world (Dykgraaf et al., Reference Dykgraaf, Matenge, Desborough, Sturgiss, Dut and Roberts2021; Low et al., Reference Low, Hinsliff-Smith, Sinha, Stall, Verbeek and Siette2021). Although this study focused on exploring experiences in one province, findings may be relevant to other jurisdictions given the ubiquitous nature of the restrictions implemented internationally. In this study, we identified five key themes regarding the impact of these restrictions: (1) changing public health and IPAC policies, (2) shifting care partner roles as a result of visitor restrictions, (3) resident isolation and deterioration from the care partner perspective, (4) communication challenges, and (5) reflections on the impacts of visitor restrictions. Availability of resources for care partners and caregiving was a concept that crosscut the themes described.

As a policy intervention, visitor restrictions were implemented to minimize the spread of COVID-19. However, guidance from the province of Ontario and the Public Health Agency of Canada were not always clear. Furthermore, individual institutions could implement additional restrictions above and beyond those recommended by government agencies, an opportunity that several institutions availed themselves of when facing outbreaks, high death rates, lack of resources, intense media attention, or any combination thereof. Cited as “overly restrictive reactive policies” (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021), they were implemented because of the rapid and deadly spread of COVID-19 in these settings, with some long-term care homes in Ontario requiring military intervention to support daily care (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus [COVID-19], 2021).

Heterogeneous polices and their variable implementation was not only an issue in Ontario, but also one that challenged care partners around the world (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021). Chu et al. (Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021) reported that long-term care visitor restrictions were implemented in many countries including China, Japan, the United States, Switzerland, Brazil, and Canada, all with varying strategies. For example, in Switzerland, decisions on restrictions were left to individual long-term care homes with little government guidance (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021). In Brazil, given the political crisis, mixed messaging regarding visitor restrictions was delivered with some recommending banning all visitors and others simply limiting the number of visitors (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021). In the United States, monthly guidance and policies were provided. However, as the pandemic unfolded, individual institutions could implement restrictions according to the number and severity of COVID positive cases (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021). Despite the heterogeneity observed provincially and internationally, our participants described similar overarching policies across the different settings, at least early on.

The intent of visitor restrictions was to protect a vulnerable population from severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection. Our study participants agreed in principle that the restrictions accomplished this. Indeed, several participants reported positive experiences and feeling their loved ones were safe during difficult and tenuous times, which aligns with results from a survey study in the Netherlands in which 67 per cent of respondents agreed that restrictions protected residents (Wammes et al., Reference Wammes, Kolk, van den Besselaar, MacNeil-Vroomen, Buurman-van Es and van Rijn2020). However, all participants expressed frustration, sadness, and even anger during new or abrupt restrictions. Nash, Harris, Heller, and Mitchell (Reference Nash, Harris, Heller and Mitchell2021) echo these findings, with sadness, trauma, and anger being the most reported emotions among 518 care partners surveyed.

Compounding the feelings of frustration, participants reported confusion in determining which “essential” care partners could visit. One complicating factor was that the definition of an “essential” care partner was not clear and varied from institution to institution. In addition, policies targeting this population were not implemented either early or uniformly, which led to feelings of helplessness and resentment. Stall, Johnstone, et al. (Reference Stall, Johnstone, McGeer, Dhuper, Dunning and Sinha2020), advocate that residents, rather than institutions, should determine who is essential to support them in their care. The Long-Term Care Homes Act (2021) in Ontario also supports this, stating that it is the right of every resident to “receive visitors of his or her choice…without interference.”

Participants in this study described how visitor restrictions affected themselves, as well as their perceptions of the impact of these on the older adults. For the older adult, these effects included disruption or modification of necessary care and support that were provided by care partners, family, friends, and contracted service providers. Pre-pandemic, substantial amounts of care, estimated at 10–30 per cent of total care, was provided by family care partners (Konietzny et al., Reference Konietzny, Kaasalainen, Dal-Bello Haas, Merla, Te and di Sante2018; Qualls, Reference Qualls2016). However, these contributions were often unrecognized and “invisible” (Kemp, Reference Kemp2021) until the care partners were no longer allowed to provide that care. Care partners posited that the isolating effects of these disruptions contributed to a decline in the older adult’s quality of life and health (mental, physical, and social), and – in some cases – believed that premature decline and death were caused by these disruptions. This position of social isolation from restricted visiting leading to deteriorations in health is not new, with previous research, including from the SARS era of 2002–2004, foreshadowing these declines (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Reference Gerst-Emerson and Jayawardhana2015; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Green, Dickens, Richards, Taylor and Edwards2011; McCleary et al., Reference McCleary, Munro, Jackson and Mendelsohn2006; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). Current literature continues to support the link between social isolation and negative health outcomes among older adults (Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Aelick, Babineau, Bretzlaff, Edwards and Gibson2021; Hindmarch et al., Reference Hindmarch, McGhan, Flemons and McCaughey2021). For example, social isolation of long-term care residents has been associated with negative mental health outcomes, including new or worsening depression, responsive behaviours, cognitive decline, and suicidal ideation (Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Aelick, Babineau, Bretzlaff, Edwards and Gibson2021). Among 1,997 care partners surveyed in The Netherlands, less than half (40%) of respondents believed that the protection provided by the restrictions against COVID outweighed the negative consequences to their loved ones (Wammes et al., Reference Wammes, Kolk, van den Besselaar, MacNeil-Vroomen, Buurman-van Es and van Rijn2020). However, despite these harmful effects, many of our participants described how they believed the visitor restrictions were, at times, commensurate with the risk posed by exposure to COVID-19 from non-residents and non-staff in those settings.

Care partners described how the visitor restrictions had direct effects on themselves, including negative health outcomes such as stress, depressive symptoms, and grief. Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs, and Tian (Reference Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs and Tian2021) similarly reported consequences for care partners of those living in congregate settings, with 73 per cent of 177 survey respondents presenting with moderate to severe anxiety (compared with 22% pre-pandemic), and 79 per cent presenting with loneliness (compared with 35% pre-pandemic) (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs and Tian2021).

Our findings suggest that the effects of visitor restrictions are multifaceted. Although the implementation of blanket visitor restrictions may have been considered in the context of balancing risks and benefits for older adults in these settings, their care partners, and the whole institution or community where the person resided, many participants in this study disproportionately reported negative effects over the proposed benefits of the restrictions. This suggests that risk assessment and decision making may need to be performed at the individual level, including assessment of the individual person’s abilities, resources, and health, to mitigate unintended harms. This type of balanced approach is recommended by Stall, Reddy, and Rochon (Reference Stall, Reddy and Rochon2020) who support the prioritization of equity over equality. To achieve this, policy makers should consider flexibility around timing and location of visits, length or frequency of visits, absolute restrictions on physical contact (with considerations for residents with cognitive impairment and/or behavioural issues), and having the resident (or substitute decision maker) determine who is essential to their care (Stall, Johnstone, et al., Reference Stall, Johnstone, McGeer, Dhuper, Dunning and Sinha2020). The application of strict blanket policies has revealed the fragility of the person-centred care philosophy and practices espoused by different institutional care settings, ministries, and health professions, and suggests the need for renewed attention to the implementation of these practices.

The availability of resources (or lack thereof) to support care partners and caregiving crosscut most themes in this study. There was a noted lack of resources for care partners and older adults, including training/education, mental health supports, and formal care. For example, participants spoke about assistive technologies, such as Web-based videoconferencing, as important tools to facilitate communication and connection. However, they also described the limitations and possible unsuitability of these adaptive approaches in the context of older adults with different physical and cognitive abilities (e.g., hearing loss, dementia, lack of physical dexterity). These findings are similar to those of Chu, Donato-Woodger, and Dainton’ (Reference Chu, Donato-Woodger and Dainton2020) who describe how these technologies may be inaccessible for those with physical and cognitive difficulties, or who simply lack technical proficiency to use them without training. Further, they point out how many institutions lack access to accessible devices that enable the use of videoconferencing. This highlights the need for investment in the infrastructure required to enable more equitable use of communication technologies in these settings, including user-friendly, accessible technologies designed for persons with different abilities. Finally, the pandemic has highlighted the need for increased staffing resources in these settings. This notion was endorsed by care partners who emphasized the many services they provided to their loved ones that were no longer provided when all care fell to institution staff. This is especially important in the context of chronic health human resources shortages that have only been exacerbated by the pandemic (Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults et al., Reference Schulz and Eden2016; Sinha, Reference Sinha2015; Stall, Campbell, Reddy, & Rochon, Reference Stall, Campbell, Reddy and Rochon2019; Stall, Johnstone, et al., Reference Stall, Johnstone, McGeer, Dhuper, Dunning and Sinha2020), and represents a broader issue with respect to health care funding and ensuring adequate resources of all types to care for residents in these settings.

Participants in this study helped identify important recommendations to improve policies in the future. Some care partners expressed that their well-being was dependent on that of the older adult to whom they provided support, highlighting the importance of creating balanced policies. They also expressed the need for enhanced communication and emotional support and recommended that new support systems become available. This recommendation is supported by Kent, Ornstein, and Dionne-Odom (Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020), who encouraged social support calls and resource navigation programs for care partners. Some of our study participants expressed frustrations with the lack of communication regarding their loved one’s health status during the pandemic. A specific recommendation to address this is to implement a communications officer position. Additionally, recommendations in the literature suggest adapting telehealth when treating and assessing patients to include care partners during these visits (Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020). This could also be implemented during routine room visits or mealtimes to allow for more regular communication. The importance of strengthening institutional communications with family care partners was also recommended by Hado and Friss Feinberg (Reference Hado and Friss Feinberg2020). One way to achieve this is to assign specific staff members as primary contacts for families to facilitate regular communications. In support of this, Wammes et al. (Reference Wammes, Kolk, van den Besselaar, MacNeil-Vroomen, Buurman-van Es and van Rijn2020) reported that care partners were most satisfied when nurses would inform them by phone about their loved one. Strategies such as these would have been beneficial for participants in this study, as many worried about their loved ones not receiving the care they needed.

This study has some limitations. First, our participants were all caring for a resident in a care institution in Ontario, Canada. Generalizability to other jurisdictions may therefore be limited, and results are not intended to represent all care partners. However, early in the pandemic, similar restrictions were implemented in many countries, and therefore we anticipate that there may be common learnings. Next, although all our participants highlighted similar themes and shared concerns, visitor restrictions were heterogeneous across institutions, making it difficult to determine which policies contributed to different aspects of their experiences. One example of this was the care partner whose loved on resided in an inpatient rehabilitation unit within a complex continuing care setting during the pandemic. These participants may have been subjected to different visiting restrictions at different times within the hospital system than in other institutions; however, they described similar experiences and challenges with communications, changing policies, and negative impacts of the restrictions. In addition, large outbreaks of COVID may have led to differing restrictions influencing care partner experiences; however, we did not collect these data because of potential privacy concerns with inadvertently identifying the institutions based on the size of their outbreaks. Finally, although we attempted to reach a diverse group of participants through various sampling strategies, we did not collect information on participants’ ethnicity, race, or culture. Therefore, we may not have captured the diversity of experiences of certain groups of care partners who may have been impacted differently or disproportionately by the visitor restrictions. Future research should seek to capture care partner experiences on a larger and broader scale, including individual, as well as institutional diversity.

There are also important strengths to this research. Although literature in this area is emerging and there is recognition of the challenges faced by care partners, many existing studies are quantitative survey based, with qualitative information gathered by free-text questions. The addition of qualitative interviews and encouraging participants to guide the conversation adds vital information, context, and depth of knowledge to this evolving area of study. In addition, we engaged older adult and care partner mentors to assist with development of the interview guide, data collection tools, and methods of dissemination, to ensure that we asked the right questions of the right people.

Conclusion

This research provides important insight into the effects of visitor restrictions on family and friend care partners. Future public health measures in care institutions must offer a balanced, and person- and family-centered approach to protect both the safety and quality of life of those living and caring for persons in these settings. As the pandemic has progressed, reports from various organizations and government bodies have emerged detailing recommendations to improve the quality of care in these settings (e.g., Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, & Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2020; Marrocco, Coke, & Kitts, Reference Marrocco, Coke and Kitts2021). These reports and the findings of this study should be considered when conceptualizing and implementing future public health measures that may restrict care partner access to the persons they support.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the essential contributions of the participants who shared their experiences with us, as well as our citizen mentors from the Canadian Frailty Network Interdisciplinary Fellowship Program, who provided insight into interview structure and design. This research is funded by Canadian Frailty Network (Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network), which is supported by the government of Canada through the Network of Centres of Excellence (NCE) program.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S071498082300017X.