A peasant named Pakhom leaves his cramped Russian village in search of more land. He grows increasingly greedy, buying ever more of it, and ultimately perishes during his most spectacular transaction in the faraway imperial periphery of Bashkiria, famed for fire-sale prices. Pakhom stakes 1,000 rubles on a land parcel as large as he can walk around in a day, agreeing to the condition that he must return to his departure point by sundown. He does, but dies of exhaustion that very moment. In this 1886 moral parable for the common reader by the title “Mnogo li cheloveku zemli nuzhno?” (How Much Land Does a Man Need?), Lev Tolstoi answers the question from his own title in the following way: the three arshins, or roughly six feet, that it takes to bury Pakhom, is exactly how much land anyone needs.Footnote 1

This is an unsurprising sentiment for the radical late Tolstoi, who by then had renounced, or was far along in renouncing, private property, all forms of violence, sexual intercourse, the consumption of meat, the legitimacy of state power, and the Russian Orthodox Church. Yet the story's meditation on settler colonization in Bashkiria, a region in the southern Urals, east of the Volga, has a little-known autobiographical angle. For much like Pakhom, Tolstoi actually purchased land in Bashkiria at bargain prices.Footnote 2 The story captures the moment when the pioneering cachet of this colonial venture has soured into moral turpitude for Tolstoi. For us today it opens a window onto the interrelated larger questions of the author's biography and intellectual evolution, the history of Russian settler colonialism, and the literary culture of imperialism that this article will explore.

In filling the biographical lacuna about Tolstoi's estate in Samara Province, I focus on new and little known legal and economic facts that I have assembled from printed sources and from my archival research in Samara, Tula, and Moscow. Apart from the lieu célèbre of Tolstoi's ancestral Iasnaia Poliana, south of Tula, the Samara estate was an important second site of the Tolstoi family's economy, leisure, and social activism for at least two decades since the 1870s, deserving greater and more consistent integration in this famous author's biography. As I show, the Samara “farmstead” (khutor), as the family called it, was not a modest vacation retreat, as it is commonly described, but an enormous estate that was acquired for profit and eventually generated a huge inheritance for Tolstoi's children.

I link the provenance, acquisition, and transformations of this estate to the Russian colonization of Bashkiria, which in the nineteenth century corresponded to Orenburg and Ufa Provinces and parts of Kazan and Samara Provinces. As such, the estate functioned within the imperial enterprise of consolidating Russian rule through transferring native people's land to Slavic settlers. Tolstoi's ownership of this estate thus provides a high-profile microhistory of this process that comes with this thoughtful historical actor's personal, intimate reflection. Along with site-specific historiography, I engage the emerging field of settler colonial studies, which theorizes settler colonies as distinct colonial formations possessing unique structural features, legitimation strategies, and discursive tropes.

These productive contexts allow us to refine and reframe key aspects of Tolstoi's intellectual and artistic trajectory. The Samara landholding experience played an integral role in Tolstoi's radical rethinking of the basic tenets of social life, especially his rejection of private property. It fed his fascination with settler colonization, which he viewed as Russia's providential mission. This neglected angle reopens in turn the question of the writer's relationship to empire, unduly narrowed to his depictions of the conquest of the Caucasus. Was the author of Hadji Murad, regarded as Russia's premier anti-colonial conscience, a colonial landowner?

Indeed, this article argues that Tolstoi's intellectual and ethical views of empire require a reassessment. Overpraising the writer's condemnation of brute conquest, however commendable, we have ignored his support for settler colonization. In essence, Tolstoi's vision of empire is not free of Tolstoian contradictions. While deromanticizing the Caucasus, he romanticized the steppe. While evoking the suffering of the victims of conquest, he turned a blind eye to the suffering of displaced nomads. Tolstoi's relation to his Samara land evolved greatly over time, but his conscious and willing participation in the colonization of Bashkiria problematizes the writer's purported anti-colonialism and reveals the complex pathways connecting his ideas about the Russian peasant with the politics of empire. Settler colonial societies, such as the United States, Australia, or Russia, are particularly resistant to decolonization.Footnote 3 Tolstoi's case shows how settler colonial myths are particularly resistant to demystification.

From Kumysnik to Colonial Landlord

Apprehensions about the possibility of consumption led Tolstoi to Bashkiria in 1871 to seek the curative effects of kumis (kumys), a drink prepared by local Bashkirs from fermented mare's milk. The kumis cure was then popular among tubercular patients, who were also drawn by the steppe's dry air. Accommodation in a Bashkir yurt and a diet of mutton and kumis (no grains, vegetables, or salt) gave Tolstoi an enjoyable respite from “civilized” cares. Since kumis was slightly alcoholic, the future prophet of abstinence was also tipsy from morning till night. He returned home feeling healthy and refreshed, fascinated by the Bashkirs’ “primitive” nomadic lifestyle and by this relatively new region of the empire. That autumn, he made his first land purchase.

Either alone, with friends, or with the whole family, Tolstoi visited his Samara estate, enlarged in 1878, in all but two summers in the 1870s. This was a period of intensive work on Anna Karenina, which bears several Samara imprints. Sofia Andreevna chafed at the heat and rudimentary amenities but valued the restorative effect of steppe life on her husband, who delighted in romping shirtless through the steppe. He formed a special bond with his seasonal kumis provider, Muhammad Shah Rakhmatullin, who read the Quran in Arabic and spoke Russian well, so Tolstoi loved to frequent his “salon,” as he jocularly called Muhammad's spotless carpet-lined yurt. This cultured Bashkir inspired Tolstoi to read the Quran in French. The Tolstoi children and various guests left colorful accounts of those summers, which included trips to the countryside, hunting, visits to country fairs, interactions with exotic natives, and horse races that Tolstoi organized on his estate. To this day, locals commemorate Tolstoi by holding horse races on the same spot.Footnote 4

Vacationing, naturally, was easier than tilling the steppe's virgin soil, which Tolstoi compared to gambling (azartnaia igra): fabulous harvests alternated with crop failures and even famines.Footnote 5 In one of his most effective acts of social activism, for which he is still revered in the region, in 1873 Tolstoi spearheaded a national campaign of famine relief for the Samara peasants, incensed by governmental denial and inaction. His appeal, printed in Moskovskie vedomosti (Moscow News), publicized the suffering of starving Russian settlers, initiating a national campaign that raised 172 tons of grains and nearly 1.9 million rubles.Footnote 6 Scenes of the Samara famine, transposed to Ukraine, appear in Tolstoi's story “Dva starika” (Two Old Men, 1885). Tolstoi also helped the resettled community of Molokan sectarians. When in 1897 the government took away their children and placed them in a Russian Orthodox monastery, their distraught parents turned to Tolstoi for help. He wrote letters to high officials, including the tsar, and publicized their plight in a newspaper, contributing to the children's eventual return to their parents.Footnote 7

As an absentee landlord, Tolstoi relied on others to manage the estate, 700 miles distant from Iasnaia Poliana. It became a shelter for all manner of non-conformists with whom Tolstoi sympathized. The Tula nobleman Aleksei Alekseevich Bibikov, hired as a manager in 1878, had been exiled for his involvement in the assassination attempt on Alexander II, later married a peasant woman, and distributed his land to peasants. His decision to dress and work like a peasant likely inspired the writer. Tolstoi also leased some Samara land to his children's former tutor, Vasilii Ivanovich Alekseev, whose colorful past included a failed Russian communist colony in Kansas. Both men were under secret police surveillance, as were the motley crew of intelligentsia liberals visiting them for the kumis cure, and Tolstoi himself.Footnote 8

Though he considered Bibikov an unassailably honest person, Tolstoi grew dissatisfied with his management. The estate sometimes had to be supplemented from other income. Bibikov's leniency toward peasants was amplified by his boss, who disapproved of using legal means in case of disputes. Though they eventually reconciled, Tolstoi blamed Bibikov for the failure of the horse farm he launched in 1875, which crossbred Kazakh and Russian horses for use in the cavalry.Footnote 9

The challenges of proxy management and moral qualms about the gap separating wealthy landowners from peasant settlers led Tolstoi in the 1880s to dub his Samara estate his “Eastern Question.” The term referred to Russia's rivalry with the Ottoman empire, seen in Russia as a vexed problem of its Asian politics. In 1883, Tolstoi decided to solve this problem by liquidating the estate, which by then weighed on him like a sin. He wanted to distribute the land to settlers for free. Sofia Andreevna, however, in whose care Tolstoi left their eight surviving children as well as the management of all estates and family finances, viewed her husband's newfound principles as selfish and ruinous to their children. Wary of antagonizing her, Tolstoi leased his land to the peasants in 1883, the year of his final visit, while selling all inventory and farming equipment.Footnote 10

Yet both the headaches and the moral qualms persisted. By June 1884, the agent hired the year prior to oversee the estate's liquidation quit and left behind 10,000 rubles in uncollected debts. Facing pressure at home, Tolstoi pleaded with Bibikov to pursue reasonable rent collections, hoping to convert retrieved moneys to an emergency fund for the peasants’ use. He claimed to be motivated “less by a desire to do good than by a desire to lessen his guilt.” Sofia Andreevna, to whom Tolstoi had given power of attorney in May 1883 along with royalty rights to all pre-1881 works, put an end to this philanthropic scheme and demanded that the money be sent to her. Bibikov quit that fall while keeping his land lease. Henceforward, Tolstoi's son Sergei Lvovich supervised the estate with the help of hired managers until it was divided among his younger siblings in 1892.Footnote 11

With the exception of Rosamund Bartlett, who provides the amplest detail, Tolstoi's biographers tend to skim over the Samara estate, reducing it to an episode of exotic local color (the Bashkirs and their kumis) and to Tolstoi's social activism on behalf of famine victims. They explain Tolstoi's purchase as motivated by health reasons and his fondness for the region, as if it were necessary to buy thousands of acres to vacation there or partake of the kumis cure (plenty of seasonal kumysniki certainly did not). Bartlett may be alone in clarifying that Tolstoi had hoped to make a profit, though she stops short of saying if he did. Until now, no inquiries were made into the property's provenance or its role in the Tolstoi family's economy.Footnote 12 Russia's imperial expansion into the steppe underpins Bartlett's account and some sources mention settlers, but they typically avoid the colonial angle and ignore the dispossession of indigenous people.Footnote 13 The one exception is Viktor Shklovskii who in his biography of Tolstoi vividly paints the monumental colonial swindle that assisted Bashkiria's transformation into Russia's colonial periphery. Yet Shklovskii's Tolstoi emerges unsullied by this context, on the feeble pretext that he did not purchase his land directly from Bashkirs. Shklovskii's provocative inquiry ultimately dead-ends in what he presents as a contradiction, whereby “a man who rejected private ownership of land made two purchases in the Samara Province amounting to six thousand desyatiny of land.”Footnote 14

How Much Land Does Prince Tul Need?

Tolstoi, whom Bashkirs called Prince Tul (meaning the Tula Prince), made two land purchases in the Buzuluk District of Samara Province, eighty-five miles southeast of the city of Samara, near the villages of Gavrilovka and Patrovka (today, Alekseevsk District of Samara Oblast). Both were financed by royalties from his masterworks, which establishes a tantalizing link between literary and colonial property. Flush with cash from the publication of War and Peace, on September 9, 1871, Tolstoi purchased 2,500 desyatiny. On April 12, 1878, using proceeds from Anna Karenina, he acquired the adjacent lot of 4,022 desyatiny.Footnote 15 While these figures are known, their significance has escaped scrutiny. These purchases’ combined area of 6,522 desyatiny, equivalent to about 27.5 square miles, is roughly 20% larger than the island of Manhattan. Though no match for the region's colonial latifundia of 50 or 100 thousand desyatiny, this was not some rustic retreat Tolstoi bought on a whim, but the biggest real estate transaction of his life.

Indeed, this land dwarfed Tolstoi's land holdings in Russia proper. The writer's 1847 inheritance of 1,481 desyatiny in Iasnaia Poliana dwindled to 370 desyatiny after Tolstoi sold parts of it to his serfs or to pay off gambling debts. In 1870 he inherited 1,153 desyatiny in the Tula Province from his brother Nikolai. This means that Tolstoi's land in central Russia comprised only between 6 and 19 percent of the total land he owned. Based on estate size rather than permanent residence, it would be more accurate to call Lev Tolstoi a Samara, rather than a Tula, landowner.Footnote 16 The first parcel was purchased for 20,000 and the second for 42,000 rubles, or the price of eight and ten rubles per desyatina, respectively. While not exactly rock-bottom prices as in the story about Pakhom, these were nonetheless incredible bargains by comparison with the cost of arable land in central Russia.Footnote 17

It bears remembering that the young Tolstoi was not yet the prophet of austerity, but an intrepid businessman who zestfully engaged in for-profit economic activity. In a letter to his skeptical wife, he describes the 1871 purchase as “fabulously profitable [vygodnosti basnoslovnoi], like all purchases here,” promising “ten times our [Russian] income, and one-tenth the trouble.” With good harvests, he writes, the investment pays off in two years, though the risk of losses in bad harvests is real. He contemplates an even more profitable purchase in Ufa Province, where Bashkirs sell land for three rubles per desyatina: “Just imagine: forests, steppes, rivers, springs, and the land is all feather-grass steppe untouched from the creation of the world, giving the best wheat, and just 100 versty from a steamship route.” Only reluctance to disrupt his kumis cure stopped the writer from pursuing this enticing bargain. This letter celebrates the fecund primordial wilderness empty of aborigines that awaits the Russian settler who will raise the curtain of history.Footnote 18

Since the Iasnaia Poliana income and produce supplied the large family's immediate household needs and expenses, the Samara lands were the principal source of liquid cash other than royalties. They helped pay off the Moscow house. Judging by 1881, good harvests meant between ten to thirty thousand rubles in annual profit, depending on the reinvestment toward the next year's crops. Droughts, however, made profits unreliable. After Tolstoi liquidated his own farming operation, rents brought over 130,000 rubles in income over twelve years.Footnote 19

Despite the boom-and-bust cycles of agricultural production on the steppe, the land itself became the best investment of Tolstoi's life. It secured the patrimony of three of his eight children. After rejecting private property, Tolstoi bequeathed his own to his family on July 7, 1892. The Samara lands were divided among his youngest children, Aleksandra, Andrei, and Mikhail; a small lot also went to Lev, to supplement his inheritance of the Moscow house.Footnote 20

All the siblings’ shares were meant to be equitable, but the Samara lands’ value skyrocketed. In 1900, a local bank assessed each of the three main plots at 160,000 rubles. It evaluated Andrei's and Mikhail's lots as profitable, bringing in the annual income of 7,019 and 16,691 rubles, respectively (at merely 2,114 rubles, Alexandra's estate was an outlier because its sole crop at the time was hay). The bank designated them a secure investment, noting that the owners’ below-market rents and low-intensity farming were a poor predictor of potential profits. The scarcity of private land for sale in the area also augmented the lots’ value.Footnote 21 Later that year, the land that Tolstoi had bought for eight and ten rubles per desyatina was sold to the millionaire Samara merchant Yakov Gavrilovich Sokolov and his son at the rate of seventy-three rubles per desyatina. This was triple the value that Tolstoi estimated just eight years earlier at the division of his property. In less than three decades, Tolstoi's initial 62,000-ruble investment appreciated nearly sevenfold, leaving four of his children property worth nearly half a million rubles.Footnote 22

Bashkiria: The Colonial Plunder

Bashkiria was a land of Muslim Turkic-speaking semi-nomadic pastoralists—predominantly Bashkirs, but also Tatars, Kalmyks, and Chuvash. The Bashkirs’ transfer of allegiance from the Nogai khan to Ivan IV in the mid-sixteenth century, construed by Russians as a declaration of subjecthood, was later refashioned in nationalist historiography as a voluntary accession to the Russian empire. Temporarily content to use Bashkirs as a military buffer against the steppe's unsubdued peoples to the east, the tsars guaranteed the Bashkirs hereditary rights to their land and offered them various privileges, such as freedom to practice Islam, estate status, and reduced taxation, which gave their elite advantages that its Tatar and Kazakh counterparts lacked. Yet for two centuries, the Bashkirs had been among the most rebellious groups within the empire, especially when these privileges were gradually eroded. Only by 1812 did they cement their loyalty to the empire by fielding a 10,000-strong cavalry to help defeat Napoleon.

The region's growing security drew settlers who put economic pressures on native communities. Russian peasants were attracted by the abundance of fertile land that to them looked empty. Tatar, Mordvin, and Chuvash migrants escaping imperial burdens elsewhere were attracted by the lower taxes and the advantages of estate status (like the Cossacks, the Bashkir estate was not defined ethnically). They were followed by government administrators bearing the gifts of civilization and modern governance aimed at transforming the wild steppes into a domain of reason, order, and “usefulness.” Some 1.7 million settlers arrived on the steppe between 1796 and 1835. In 1816–34, the population of Buzuluk, Tolstoi's future district, increased by forty percent when one-third of Tambov Province resettled there. Hemmed in by the unstoppable waves of legal and illegal migrants and by imperial policies that either favored agricultural settlers or failed to meaningfully restrain them, the Bashkirs lost much land and pasture. Their cattle and horse herds declined. The ensuing destitution further increased their reliance on selling land or leasing it to landless peasants (pripushchenniki), who had the habit of becoming squatters and in cases of disputes enjoyed the administration's backing.Footnote 23

Despite partial halts and reversals, the process of dispossession progressed inexorably. The seventeenth-century prohibitions on the sale of Bashkir land were lifted in 1739. This led to a flurry of purchases by nobles and government officials who abused the Bashkirs’ unfamiliarity with the Russian market and legal norms to acquire vast tracts of land for a pittance. Recounting his grandfather's resettlement in Semeinaia khronika (Family Chronicle, 1856), Sergei Aksakov revealed that treating Bashkirs to a feast of a few fatty rams and barrels of alcohol could buy enormous parcels of land at the price of fifty kopeks per desyatina. These were demarcated in purchase deeds by such vague coordinates as a dried-up birch, a “river of unknown name,” or some fox holes. The same land might get sold twice to different buyers or resold without a title. It was common for the land value to double within less than a decade. Bashkiria's common descriptor, used also by Tolstoi, was “fabled” or “fairy-tale,” as in basnoslovnye harvests and basnoslovnye land prices. Indeed, the southeastern steppe was European Russia's most fertile region.Footnote 24

Aiming to clarify land claims and produce detailed descriptions of imperial territories suitable for sale and development, the government embarked on a General Land Survey (General΄noe mezhevanie), which reached Orenburg Province, then largely coterminous with Bashkiria, in 1798 and was concluded in 1823. Shenanigans by surveyors and bribery by nobles with interest in the land were rife, making this well-intentioned governmental intervention into yet another instance of the colonial racket. As Charles Steinwedel notes, surveying became “a pretext” to strip Bashkir communities of “reserve” land. Tolstoi's future parcel came into the state domains precisely through this General Land Survey.Footnote 25

When the Bashkirs’ dire economic situation imperiled their military service to the empire, the government banned the sale of Bashkir lands once again in 1818, then relaxed this ban in 1832. Following the Great Reforms, which according to Steinwedel were “not so great for Bashkirs,” liberated serfs descended on Bashkiria en masse, precipitating a land rush akin to California's gold rush. Between 1869 and 1878, Bashkirs lost nearly one million desyatiny of land; in the most fertile regions, losses approached forty percent. Given its timing and size, Steinwedel perceives commonalities between this Russian colonial land grab and France's 1860 seizure of nomadic Arabs’ lands in Algeria. Smaller land allotments made also new settlers worse off, exposing them to famines. Needless to say, droughts were linked to the ecology of colonial land use, which caused a massive loss of water-retaining woodlands and the disruption of ground water levels due to extractive farming. Rivers and lakes marked on maps could not be located a few years later.Footnote 26

In the minds of some imperial administrators, the solution to the ills of colonization was more colonization, in Willard Sunderland's phrase. The root of the nomads’ problem was not the loss of land but its surfeit. The solution was thus to deprive them of more land (obezzemlenie), the sooner to teach them the benefits of settled life. Of course, enforced sedentarization, premised on the notion of nomadism as pathological, is a form of biopolitical violence that paves the way to other removals and targets the indigenous people's survival by blocking their traditional economic activity.

A prominent champion of sedentarization was Tolstoi's Crimean War commander, Nikolai A. Kryzhanovsky (1818–1888), Governor-General of Orenburg since 1865. Tolstoi visited him in 1876, when in town to buy horses for his farm. A foe of both nomadism and Islam, Kryzhanovsky sponsored two pieces of legislation that further commercialized Bashkir lands. One lowered the property-holding minimum for Bashkirs wanting to sell their land. The other was an 1871 law that privileged “educated and useful” buyers, a legal fig leaf for the Russian elites. In this newest bonanza, parcels “the size of Belgium” were granted at absurdly favorable prices to nobles, officers, and officials, who reaped stupendous profits by reselling them to peasants at market prices, up to twenty-five times higher. This is the climate in which Tolstoi bought his first parcel, in 1871, though he did not avail himself of this scheme (he bought his lands in Samara Province, created in 1851, which encompassed western parts of Orenburg Province).Footnote 27

The extremity of this colonial plunder, as it was called (razkhishchenie), stirred Russia's civil society. By 1880, the popular press elevated the issue into a national scandal by portraying Bashkirs as victims of a corrupt, predatory state that cared only for the enrichment of its officials. An investigation ensued, but though it uncovered improprieties, few lands were returned to native people. In 1881, Kryzhanovsky was disgraced and stripped of the Governor-General post, which was abolished altogether. He dragged down with him the former Minister of State Domains, Petr Valuev, who was asked to retire.Footnote 28

It is around this time that Tolstoi decided to liquidate his Samara estate. While both the challenges of remote management and his moral qualms about private ownership of land mounted beforehand, the scandal's eruption likely hastened or encouraged his decision to liquidate his estate in 1883 and to divest himself of it in 1892. Owning land in Bashkiria lost its aura of historical romance and acquired the stigma of public opprobrium. Tolstoi's “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” was a topical publication indeed, yet one that preached a lesson on colonial greed to peasants at a time when nobles and officials were in greater need of it.

Similarly miscast is Tolstoi's critique of private property in another story for the common reader, “Il΄ias” (Ilyas, 1885). Here Bashkirs, of all people, play the role of greedy capitalists. When the fabulously wealthy cattle herder Ilyas loses his fortune in his old age, he and his wife hire themselves out as simple workers to another affluent Bashkir, Mukhamedshakh (named after Tolstoi's kumis-provider), and realize they had never been happier. So at a time when Russian journalism paints real Bashkirs as destitute victims of colonial plunder, and the real Muhammad Shah complains to Tolstoi about his penury (more on this below), Tolstoi's fictional Bashkirs discover that propertylessness is bliss. A more spectacular erasure of the social realities of settler situations may be hard to find in the colonial archive.Footnote 29

The Estate's Provenance

The elite servitors from whom Tolstoi acquired his land were Generals of the Infantry who were granted state lands in Samara Province in 1864 by Emperor Alexander II in reward for meritorious service. Tolstoi's first 1871 purchase was the property of the Governor-General of Moscow, Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov (1806–1864), who was awarded land posthumously. Tolstoi bought part of it from his son and heir Nikolai Pavlovich Tuchkov. General Tuchkov was a member of the State Council, the emperor's highest advisory body, and a veteran of the Russo-Turkish war of 1828–29, the campaign against the Polish Uprising of 1831, and the Crimean War. The second seller was Rodrig Grigorevich Bistrom (1810–1886), an aide to the Commander of the Guards of the St. Petersburg military district and a member of the Military Council, who had just distinguished himself in the suppression of the Polish Uprising of 1863.Footnote 30 (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. The monument on the site of Tolstoi's second lot, purchased from Bistrom. The inscription says “This is the site of L. N. Tolstoi's farmstead (usad΄ba), which he visited in 1872–1883.” (author's photograph)

Given the timing, both land grants appear to be part of the post-emancipation boom for transfers of Bashkir land to Russian officialdom and nobility. Property documents indicate that state peasants of unknown number were settled on both lots at the time of the General Land Survey of 1800, reconfirmed in 1836. However, during the land's transfer from the Treasury in 1864, these adjacent lots lay vacant and Tuchkov's lot continued to be vacant when Tolstoi bought it. Bistrom's peasant renters would have been there only since 1868, the year he petitioned for the right to lease his land.Footnote 31 It is puzzling why the peasants would have disappeared between 1800 and 1864, a period of exponential agricultural settlement. It is possible they existed only on paper, to pave the way for the state's repossession of this land, as the presence of Russian settlers, even semi-legal or outright illegal pripushchenniki, skewed the interpretation of property rights in the Bashkirs’ disfavor.

Indeed, documents housed in the Central State Archive of Samara Oblast indicate that the land granted to Tuchkov and Bistrom was the object of a long-standing Bashkir grievance. Purchase deeds and survey registers for both properties list the area in question as “Synrian Bashmuch of the Kipchak and Kurpech-Tabyn volosti.” These were clan-based territorial units of Bashkir self-administration.Footnote 32 A vast cache of documents, mostly maps, indicates that the Bashkirs disputed the state's unlawful seizure of “Synrian Bashmuch.” It appears that the Russian administration, deeming this land “wild” (dikorastushchaia), as the land of pastoralists was perennially treated, assigned it to the Treasury through the General Land Survey of 1800, either proceeding to settle peasants on it or claiming to have done so.Footnote 33 It is unlikely that either the generals, who probably never set foot on this land, or Tolstoi were aware that the land was contested property. But this archival record suggests that although Tolstoi did not purchase his land directly from Bashkirs, as Shklovskii noted, he was two degrees removed—by the Treasury and its grantees—from their proprietary claims, which the Bashkirs considered to have been unjustly violated by the imperial state.

Settler Colonialism on the Bashkir Steppe

So where does this leave us on the question of whether Tolstoi was a colonial landowner? Broadly speaking, colonialism as practiced by modern European empires involved conquest and subsequent control of the labor, goods, and territories of ethnically or culturally different people, which restructured their economies to ensure the accrual of a wide range of benefits—economic, strategic, or other—toward the imperial core. Colonial relationships are inherently inequitable and typically exploitative. Settler colonialism was a distinct form of colonial practice that involved dispossessing indigenous populations of their land and settling exogenous communities that claimed to be normative, sovereign, and politically isomorphic with the metropole.

According to settler colonial studies, important features distinguish settler colonialism from both migration and other forms of colonialism. Unlike emigrants, settlers depend on conquest or annexation. In James Belich's famous distinction, emigrants join someone else's society, whereas settlers reproduce their own. Unlike colonial administrators, soldiers, or missionaries, settlers generally come to stay, which leads Patrick Wolfe to argue that settler invasion is a structure, not an event. While other forms of colonialism extract labor from the colonized, settler colonialism seeks to take their land. The indigenous people are therefore eliminated or displaced through some combination of physical, spatial, legal, administrative, cultural, and symbolic means whose ultimate goal, in Albert Memmi's words, is to “transform usurpation into legitimacy.” According to Lorenzo Veracini, settlers transplant metropolitan cultural and political norms while simultaneously striving to become indigenous and thus “superseding” their colonial character.Footnote 34

Settler colonialism ruled supreme on the Bashkir steppe. Yet while Russia's settlement in this and other imperial regions is an accepted fact, this settlement's colonial character remains controversial. As Sunderland demonstrates, Russian imperial discourse devised ingenious ways to justify its empire as non-imperialistic. Likewise, it promoted a view of Russia's colonization as non-colonial. These denials have shared rationales. Russian nationalism tended to downplay the peripheries’ otherness and separateness; the “magic cup” of manifest destiny made imperial expansion seem natural and inevitable; and the avowedly anti-colonial Soviet state later repackaged tsarist colonialism as progress. The conditions of continental expansion—seemingly so different from west European empires’ overseas colonialism and yet, as we now realize, quite similar to the settler colonization across the North American Great Plains or South American Pampas—blurred the boundaries between Russian and non-Russian spaces. It also fostered a perception of the Slavic settlers’ colonization as agrarian development of underutilized land.Footnote 35 Today, the notion that the Russian empire was not colonial and its actors lacked a colonial mentality is increasingly relegated to the province of imperial myths. Although the Russian empire's territorial contiguity blurred its coloniality to its agents and beneficiaries, it deserves sharper relief in hindsight. The fact that settler colonialism is premised on “obscuring the conditions of its own production,” in Veracini's phrase, only increases the importance of unmasking them.Footnote 36

Tolstoi's ownership of his Samara estate is indeed quite proximal to the colonial mechanisms operating in Bashkiria. The specific Bashkirs pushed off the land that Tolstoi later bought protested its seizure as illegal even by imperial laws. Tolstoi was up-front that profit, not kumis, motivated his purchases, and knew that the “fabulous” prices he paid were much below the land's real value, and were the ultimate result of Bashkirs being exploited. In essence, the half a million rubles’ worth of colonial property that this Russian writer passed on to his children was taken from Bashkirs. As this article's continuation shows, lured by the romantic myth of the Russian peasant's manifest destiny in the East, Tolstoi supported Slavic settlement of Bashkiria and evinced no particular regret at the indigenous people's dispossession.

During his visits to the Samara steppe, “Prince Tul” actively interacted with Bashkirs, Tatars, Nogais, and Kazakhs. He saw first-hand the transformation of the region's nomads into kumis peddlers catering to Russian consumptives and tourists. These locals discussed with him imperial depredations to their livelihood, which were known to him even before his first purchase. “They have it much worse than before,” he wrote to his wife, “The most fertile land was taken from them, so they started farming, and most of them are unable to move from winter quarters” (lack of access to summer pastures was equivalent to starving out the herds). Tolstoi's son Sergei recollects that a sharp deterioration of the Bashkir way of life was a constant conversation topic of his father's friend Muhammad Shah Rakhmatullin. He would complain how the herds have declined due to land loss and year-round confinement to winter quarters and how poverty led Bashkirs to abandon traditions of lavish feasts. Sergei blames the Russian state for taking Bashkir land and passing it on to peasants and wealthy dignitaries and for pressuring Bashkirs to adopt agriculture, for which they were ill-suited.Footnote 37 His father was a beneficiary of those dignitaries; he participated in the colonial enterprise that brought them there.

The story of Tolstoi's Samara estate illustrates the sharp economic conflict between elite landowners controlling vast tracts of land and peasant settlers whose economic well-being also declined. While the peasants resettled from central Russia mostly to escape being squeezed out by noble landowners, the nobles seem to have caught up with them after all. One way in which the state compensated the nobility for the economic pains of emancipation was to transfer into their possession the indigenous land in imperial peripheries. Because settlers were expelled from their “home countries” by political, economic, or religious pressures, and yet became agents of those countries upon resettlement, they are considered to be both colonized and colonizing in settler colonial studies.Footnote 38 Reluctant to so conceive of Bashkirs, Tolstoi viewed Russian settlers as such colonized victims of land-grabbing nobles and the incompetent state.

It is therefore even more surprising that he snatched his second Samara lot from under the settlers’ noses. A delegation of Samara peasants wishing to buy this land for their collective use traveled all the way to St. Petersburg to deliver their offer to General Bistrom. Tolstoi sniffed out the peasants’ terms from his trusted man on the ground and leveraged this information to make his own bid more attractive. Interestingly, the enterprising peasants, whom Tolstoi called his “competitors,” offered more money than the count, but instead of outbidding them, he presented himself as a more reliable buyer who would repay the balance sooner. So this large parcel, instead of going to the land-hungry settlers, enriched the big landowner and his heirs.Footnote 39

From Manifest Destiny to a Critique of (Colonial) Property

Tolstoi's enthusiasm for Russia's destiny as a settler civilization revealed itself in Anna Karenina (1878). Levin channels it in his book on agriculture, which propounds the Russian peasant's mission “to settle huge unoccupied expanses in the East.”Footnote 40 Lambasting such engines of imperial expansion as militaristic adventurism or capitalism, the novel lays trust in the supposedly peaceful agrarian empire, shepherded by landed aristocracy. As for the novel's other Samara echoes, Karenin—partly based on Valuev, who as Minister of State Domains presided over the plunder of Bashkir lands—emerges as a failed manager of both settler colonization and ethnic minorities.

With drafts of Anna Karenina still strewn on his desk, and concurrently with transacting the Bistrom purchase, Tolstoi revived an old project, the novel Decembrists, whose 1863 beginnings had morphed into War and Peace. In 1877, Tolstoi poured new wine into this bottle, turning Decembrists into a “colonization novel” (pereselencheskii roman). The project resembles a fictionalization of Levin's agricultural theses. This is how Tolstoi described it to his wife: “For the work to be good, one has to love its main idea. In Anna Karenina, I love the idea of the family, in War and Peace I love the idea of the nation, in connection to the war of 1812. It's clear to me that in this new work I will love the idea of the Russian people as a power that takes possession (sila zavladevaiushchaia).” In his wife's elaboration, this meant “the Russians’ constant resettlement to new places, like the south of Siberia, the new lands in southeastern Russia, the Belaya River [Ufa Province – E.B.], Tashkent, and so on.” But despite Tolstoi's passion for the subject, and for unclear reasons, his work on Decembrists ground to a halt in February 1879, at which point he transferred his energy to The Confession.Footnote 41

The surviving 1878 draft of Decembrists begins in the 1810s, with the land dispute between the state peasants of the village Izlegoshchi, Penza Province, and a neighboring landowner.Footnote 42 Scholars have ignored this draft's biographical echoes. At stake is the 4000 desyatiny of land—roughly the area that Tolstoi bought in Samara that same year, outmaneuvering his peasant “competitors.” Prince Chernyshev has illegally seized this land from the village commune. He is an aristocrat and a father of six children, as was Tolstoi at the time of writing. Multiple legal jurisdictions have judged in the peasants’ favor, but Chernyshev bets on the highest chamber, the State Council, intending to press the scales of justice behind the scenes. Were his crooked scheme to prove successful in the novel's continuation, the stage for the peasants’ migration to the steppe would have been set. An exiled Decembrist, likely Chernyshev's own son, was to run into and join those migrants around Irkutsk or Samara. The story is partly based on an actual source: an 1815 petition of Tambov peasants wishing to resettle to Buzuluk District. So Tolstoi's colonization novel was to feature the ancestors of his own neighbors in Buzuluk.Footnote 43 (See Figure 2)

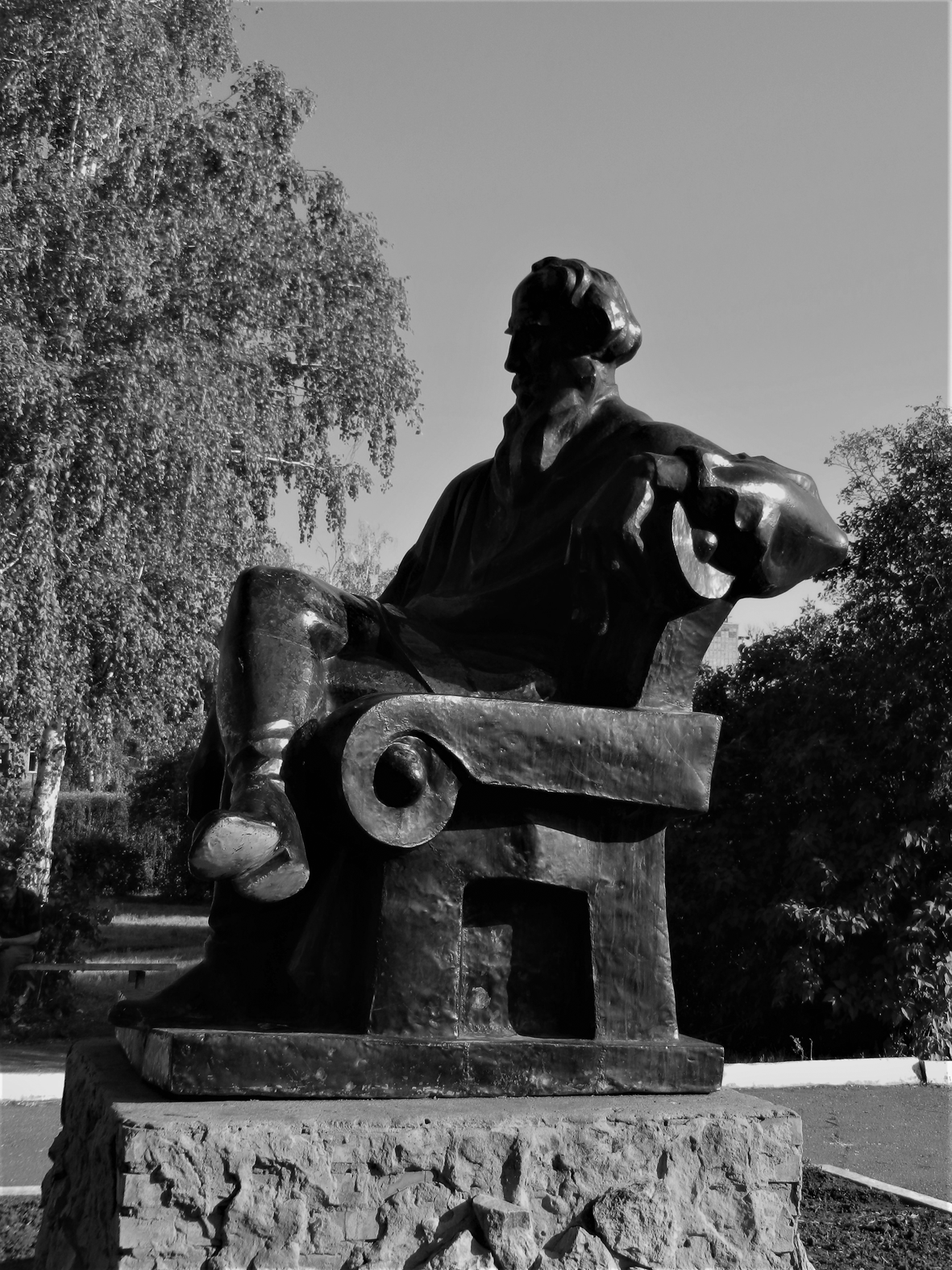

Figure 2. The monument to Tolstoi in Buzuluk, Orenburg Oblast. (author's photograph)

Like Tolstoi's other Samara-themed stories, the draft disavows colonial realities. The victims of land dispossession are not the indigenous people but the peasants. Chernyshev discounts their grievances, claiming their life is good enough without the disputed land. Tolstoi may have told himself the same about the settler buyers he outmaneuvered; the government treated Bashkir grievances this way. Chernyshev feels blameless because he personally did not seize any peasant land; his father did so forty years ago.Footnote 44 The narrator is skeptical about this legally and morally dubious rationalization. One wonders if the author also would be, knowing that his own land was seized from Bashkirs roughly forty years prior to his purchase.

The idea of settler colonization as Russia's historic destiny had an emotional charge for Tolstoi that led him to override and overwrite any troubling realities. In August 1875, returning from his steppe khutor, he comments on “the struggle of the nomadic way of life (millions on enormous expanses), with the agricultural, primitive one.” The historical process occurring in the steppe fascinates him: “no matter flies, dirt, muzhiks, or Bashkirs, I strain my eye and ear, absorbed, and afraid of missing anything, and I feel that all this is very important.” Soviet historians’ contrast between “natural” (stikhiinaia) colonization by peasants, spontaneously venturing out in search of arable land, and the predatory “landowner” (pomeshchich΄ia) variety would have likely resonated with Tolstoi. When traveling to liquidate his Samara estate in 1883, the sight of settlers struck him as “a very moving and grandiose spectacle.”Footnote 45

According to Tolstoi's wife, the story of Siberia-bound migrants from Tambov particularly fascinated Tolstoi. When their money and provisions ran out, they sowed and gathered the harvest “on the land belonging to the Kirghiz,” then continued on their way. They repeated this pattern until reaching China, where they settled on the land “abandoned by the Chinese and the Manchurians.” Tolstoi's comment on this story clarifies his notion of the Russian peasant as “a force that takes possession”: “Although the land belonged to the Chinese, it is now considered Russian, and it has been conquered not by war or by bloodshed, but by the agricultural power of the Russian peasant.”Footnote 46 Historians today vindicate this view of Russian peasants as “consummate colonizers.” Because peasant identity was tied to the people and the commune, and not to the state, anywhere they went felt like Russia to them.Footnote 47

Remarkably, even as Tolstoi's opposition to private land ownership grew, his enthusiasm for the Russian peasant's errand into the wilderness did not wane. In fact, his plan to give away his Samara land to peasants would have been consistent with both positions: while ending Tolstoi's own proprietorship, it would have facilitated the peasants’ mission to domesticate the steppe. Key to Tolstoi's thinking was a contrast between the Russian peasants’ and westernized noble elites’ ways of owning land. “La priopriété c'est le vol” (Property is theft): this adage from Pierre-Joseph Proudhon appears in Tolstoi's 1865 notebook entry, which shows that Tolstoi was contemplating the ills of property long before he officially renounced it. He prophesies that the Russian people's rejection of individual ownership of land in favor of a communal one (obshchina) will become Russia's contribution to universal progress.Footnote 48

Settler communities remain immune to Tolstoi's thoroughgoing critique of private property in his treatise on political economy, Tak chto zhe nam delat΄? (What Then Must We Do?, 1884, 1886): a critique concurrently advanced through fictional means in the story “Kholstomer” (Strider, 1885). Though inspired by the writer's work in urban slums for the 1881 Moscow census, the treatise uses landownership examples to argue that private property is the root of all contemporary evil. This conclusion echoes the Russian intellectuals’ overall distrust of property, which they associated, according to Richard Wortman, with “the sense of oppression and exploitation, of an illegitimate usurpation of the possession of all, under the auspices of arbitrary and brutal political authority.”Footnote 49 In this vein, Tolstoi argues that to usurp ownership over the land worked by others means to enslave them. Violence or its threat props such dubious claims, just as it tips the scales that measure the value of labor, making money far from a neutral means of exchange. A lifelong popularizer of the American economist Henry George, Tolstoi supported his idea of nationalizing all land and instituting a tax for using it. The Georgist Nekhliudov in the novel Resurrection (1899) gives his land over to the peasants on condition that they regularly contribute to their own emergency fund, a system that in 1894 Tolstoi had implemented, with mixed success, at his daughter's estate.Footnote 50

What Then Must We Do? is premised on each person's natural right to use land and extract livelihood from it through labor. In Tolstoi's idealized simplification, this is what Russian settlers do: they arrive in a place and work as much land as they are able. The evils such as rent, interest, or capital are foisted on them by the property regime of those who wish to exploit their labor. Alongside this example, Tolstoi recounts the Fiji islanders’ loss of land to American and British colonialists, who enslave them through fake property claims. The treatise equates the Russian settlers’ and the Fiji islanders’ traditional non-proprietary relations to land, making them parallel victims of exploitation. It evinces no awareness that in the real world, the rights of settlers and of natives may conflict, were Fiji island to become a settler destination, like Bashkiria.Footnote 51

Yet Tolstoi's personal experience of the late nineteenth-century colonial economy must have eventually made clear to him that a peasant commune was rapidly becoming a thing of the quasi-mythic past. Tolstoi himself leased his own Samara land for money to individual settlers, not to any commune.Footnote 52 Capitalistic accumulation of land-as-capital, cutthroat competition, enrichment schemes invented by state functionaries colluding with landowners, the progressive impoverishment of the agrarian proletariat, and at the bottom of this gigantic colonial racket, the exploited indigenous population: all of this fit poorly with his treatise's theoretical pictures of the peasant commune harmoniously tilling the land under the benevolent sun, harming no one. Private property ruled the steppe with a vengeance.

Tolstoi's disenchantment is on display already in “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” (1886). Matthew Mangold parallels peasant Pakhom's story with what was then known about Tolstoi's Samara estate, placing both in the context of the Russian colonization of the steppe. His article valuably pushes the biographic connection from the story's ethnographic margins—Tolstoi's familiarity with Bashkir customs—to its thematic core, centered on the question of property. Where I depart from Mangold is by considering “How Much Land” less as a story of imperial hypocrisy than of moral reckoning, at least as regards Tolstoi's relation to the Russian settlers.Footnote 53 The story dramatizes Tolstoi's own moral qualms about owning this land, which beset him in the early 1880s. The “shikhan” (hill) like the one that becomes poor Pakhom's final resting place is a topographic landmark of Tolstoi's own first farmstead, still called so by the locals. (see Figure 3)

Figure 3. The hill (shikhan) on Tolstoi's first lot, purchased from Tuchkov. (author's photograph)

Pakhom's centripetal journey of migration and colonization in pursuit of lucrative property parallels Tolstoi's own. The author eventually found it as morally ruinous for himself as he made it for his fictional peasant. When his children reaped their stupendous Samara profits selling the land in 1900, Tolstoi reportedly found his role in their enrichment morally repugnant: “It always weighs on my conscience that wishing to disassociate myself from property, I made those acts [bequeathing his property to children]. I feel ridiculous thinking that it seems as though I wanted to provide for my children. No, I perpetrated enormous evil on them It's so contrary to my thoughts and wishes, to what I live by.” Horrified by the sale, he writes in a letter, “Land cannot be the subject of property.”Footnote 54

This is precisely the premise of “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” Despite its quantifying title, the story does not merely scale down perceived human needs but rejects the idea that we can ever own anything other than the transient imprint of our bodies on earth, a message echoed in the contemporaneous What Then Must We Do? Footnote 55 Yet the story distinguishes between more and less reprehensible regimes of ownership. While the villagers initially plan to purchase local land as a commune (mirom), the devil intensifies their divisions until they buy individual lots instead (porozn΄). Each subsequent purchase increases Pakhom's alienation from the community. To raise his down payment, he apprentices his son; in pursuit of larger parcels, he emigrates from his village. His apogee as a proprietor is a nadir of alienation, as he is lowered into his lonely grave, a week's journey away from where he left his wife.Footnote 56

Bashkirs, portrayed in the story as innocent children of nature, are Tolstoi's primitive “users” of land who lay no individualistic claims of possession and happily share it with Pakhom. Their elder, however, knows all about boundaries, money, and purchase deeds because he has dealt with the likes of Pakhom before. He boomerangs the corrupt imperial practices aimed at his community by outsiders. His devilish aura is a projection of Pakhom's own demons. If the elder's condition that Pakhom complete his circumambulation by sundown seems like entrapment, Pakhom has laid that trap himself through his greed. Indeed, the Bashkirs boost Pakhom's chances by reminding him that the sun on the hilltop has not yet set when he erroneously thinks it did from his lower position on the hill. As Mangold notes, the idea of Bashkirs having no concept of land ownership is a figment of Tolstoi's colonial imagination, consistent with Orientalist projections of Russia's imperial agents that greased the wheel of colonial expropriation.Footnote 57 The story's Bashkirs are unharmed by the influx of Russian peasants.

However, although it does not countenance Bashkir suffering, the story is a parable not only of greed, but of colonial greed, and of the Russian colonization of Bashkiria writ large. The Russian peasant may not need much land, but he especially does not need Bashkir land. The story paints colonialism as the quintessence of avarice, its most extreme manifestation, in line with Lenin's dictum of imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism.Footnote 58 When returning in 1889 to the topic of peasant resettlement in his diary, Tolstoi seems to have concluded that nomads had it right all along: “agriculture, which displaces nomadism, and which I experienced in Samara, is the first step toward riches, violence, luxury, depravity, and suffering. That first step shows it all.” In other words, the lesson of Samara is not a critique of colonialism but of agriculture. In the sottovoce of his diary laboratory, Tolstoi experiments with the idea that agriculture—which he had venerated as the providential engine of Russia's imperial expansion and held as the most dignified and important human endeavor—might itself be the root of all evil.Footnote 59

The Bayonet and the Plow

Owning and managing land in the estranging conditions of the imperial periphery catalyzed Tolstoi's radical rethinking of private property, landowning, money, and even agriculture. Rather than a canvas on which Tolstoi's philosophical and moral searches were projected, the colonial steppe was one of their likely incubators.

At the same time, the transformative effects of this experience had definite limits. Tolstoi's ruthless questioning of the fundamentals of modern society did not involve a clear rejection of the Russian people's world-historical mission to settle the “empty” steppe. But the experience did put pressure on this idea, tamping down its original triumphalism. Although elements of Tolstoi's worldview—his opposition to private ownership of land or sympathy for Bashkirs—could be assembled into an argument opposing Russian settler colonization, there is little to suggest that he so assembled them. Genuine anti-colonialism was just a step away, but it was a step too far.

This was an important blind spot in Tolstoi's moral and social calculus of such colonial situations. His moral reckoning as a colonial landowner focused on his contribution to the pauperization of the Russian peasant, not the dispossession of the Bashkir nomad. The tragedy of Bashkiria was for Tolstoi the tragedy of the Russian settler, exploited by large landowners, neglected by government officials, oppressed by rents, exposed to the risk of crop failure and famine. For all their exotic charms, Bashkirs did not figure in his vision as social subjects whose situation demanded remedy. The Bashkirs’ fate was to cede the historical stage to the Russian peasant, so why wring one's hands on their behalf? The question “what, then, must we do?” could only be asked about the Russian peasant, but not the nomad he relentlessly displaced.

Tolstoi's moral nausea about his children's lucrative sale of the Samara land hinged on a realization that they “live at the expense of the people (narod), which I once robbed, and which they continue to rob.”Footnote 60 That narod was the settlers, not the indigenous people. Nowhere does he designate Bashkirs as the victims of his own or the state's robbery. Despite the influx of speculators, the Bashkirs from “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” lose none of their cheerfulness. Tolstoi's rejection of property and growing unease about agriculture likely caused him to consider Bashkirs as people saved from the degrading notions of property. Yet even earlier, they were invisible to him as colonial victims, though he knew about their plight. Tolstoi's famous 1873 appeal for famine relief details the sorry particulars of every tenth household in the village of Gavrilovka. No mention is made of the Bashkirs, who by then suffered from famines more than the settlers.Footnote 61 It is unlikely that the aid Tolstoi helped organize was extended to their communities.

Tolstoi is hardly an exception. His view of colonization was consistent with that of Russian society generally. “The nomads—whether understood as victims of official neglect or as beneficiaries of civilization or some combination of both,” Sunderland writes, “were not the primary focus for most of the steppe's educated observers. That honor remained with the colonists themselves.” As Kulturträgers, colonists were the mesmerizing “nation in motion,” fitting heroes for Tolstoi's colonization novel.Footnote 62 To dwell on Tolstoi's failure to transcend the spirit of the time is neither unrealistic, unfair, or ahistorical, however. Subverting bedrock notions of his culture and time was the late Tolstoi's bread and butter. Besides, since the 1880s, the empire's emerging public sphere began to take up the cause of various imperial minorities, like Nikolai Yadrintsev's famous championship of Siberian aborigines. So this concern was clearly “thinkable” to Tolstoi's contemporaries, including the Russian journalists who shamed the government for swindling Bashkirs.

The biographical fact of Tolstoi's colonial estate does not nullify his impassioned championship of the humanity and pathos of the victims of imperial conquest, on full display in his works about the Caucasus.Footnote 63 But it does make Tolstoi's image as tsarist Russia's anti-colonial writer shade into gray. Too ensnared in the contradictions of his time, he denounced the brutal conquest of the Caucasus while also admiring the peasant's restless drive, not confronting its effect on native people either in the Caucasus or Bashkiria. The question of empire in Tolstoi's art and thought thus deserves reframing. Transfixed by the high drama of conquest, we have overlooked the humdrum sideshow of colonization. While rejecting the imperial bayonet, Tolstoi glorified the imperial plow, legitimizing it as an acceptable instrument of imperial expansion.Footnote 64 He was blinded to its injustices due to settler colonization's pervasive normalization in Russian culture as agrarian development as well as his populist-nationalist idealization of the Russian peasant, who emerges unscathed from the fires of the writer's philosophical and personal anti-property rampage.

To view empire through the lens of settlement colonization opens the question of means and ends. Did the grace of colonization redeem the original sin of brute conquest for Tolstoi? After all, his poignant critiques of the iniquities of conquest do not necessarily connote an opposition to the very idea of empire. An interpretation of the writer's Caucasian corpus would benefit from this distinction. To regard Tolstoi's vision of a morally compromised empire as more complex and equivocal may seem like a diminishment. But the gain is a humbling recognition of the pressure of the historical moment that can bend even such clearsighted moral beacons as Tolstoi.