Criteria for diagnosis of personality disorders have been established in the two international classificatory systems, ICD–10 (World Health Organization 1992) and DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Both systems are atheoretical in nature, i.e. based not on any causative explanatory paradigm but on expert consensus. Their approach to diagnostic classification has major problems that are so serious that, in our experience, many practitioners question the value of making a diagnosis of personality disorder at all.

Given that both ICD–10 and DSM–IV are in the process of revision,Footnote † we begin with deficiencies of the current systems that have been identified as being especially important. First, the current systems are neither theoretically sound nor empirically validated (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007; Reference Tyrer, Coombs and IbrahimiTyrer 2007). Second, they pose problems not only of overlap (an individual might satisfy several personality disorder diagnoses) but also of inadequate capture of important clinical aspects of personality pathology (e.g. sadistic and passive–aggressive traits) (Reference Westen and Arkowitz-WestenWesten 1998). Furthermore, the current systems are not sufficiently discriminating, so a substantial number of individuals are classified as having a ‘personality disorder not otherwise specified’ (Reference Verheul and WidigerVerheul 2004). Third, clinical assessments of personality disorder have been shown to be very unreliable and self-report inventories have been shown to generate too much psychopathology (Reference ZimmermanZimmerman 1994). Although semi-structured instruments show an acceptable level of reliability, their administration is cumbersome and often requires considerable training. Consequently, their utility for many practitioners is limited. Moreover, the concurrent validity between these instruments is poor: someone who meets criteria for a personality disorder with one instrument might not do so with another. This is clearly unsatisfactory. Finally, and most importantly, the current classificatory scheme is unhelpful in treatment selection (Reference Sanderson, Clarkin, Costa and WidigerSanderson 2002; Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007). As treatment selection is usually the reason for assessing the individual in the first place, this failure to follow up quite detailed assessments with a coherent treatment plan can be disheartening for both patient and clinician.

These shortcomings relate predominantly to differences between two schools of thought on classification: the categorical and the dimensional. These differences are due to philosophical and theoretical approaches that distinguish the biological and the social sciences: medical systems belong to the former school and psychology to the latter.

The categorical approach

Both ICD–10 and DSM–IV identify categories of personality disorder. In keeping with their medical origins, the two schemes promulgate a system for diagnosing personality disorder that is categorical in nature: people are thought either to have a personality disorder or not to have one. The categorical approach has a two-component structure – generic criteria to make a diagnosis of personality disorder, and specific criteria for the different types of the disorder. The generic criteria (Box 1) seek to separate personality disorder (DSM Axis II disorders) from other mental disorders (DSM Axis I disorders), whereas the disorder-specific criteria attempt to distinguish different types of personality disorder (e.g. borderline and narcissistic) from one another.

BOX 1 Generic criteria for a diagnosis of personality disorder

Characteristic features:

-

• maladaptive thinking, feeling, behaving and social functioning

-

• developmental origin, tend to be lifelong, relatively inflexible

-

• clinically significant distress to self and others

-

• thinking, feeling, behaviour and social functioning deviate markedly from cultural norms

-

• not due to any other mental or medical condition

Disorder-specific criteria

The trait is adopted as the basic descriptive unit, and is defined in DSM–IV–TR as ‘[behavioural] patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself’ (American Psychiatric Association 2004: p. 630). There is much confusion as to how a trait should be defined and/or described. Each trait within the classificatory systems consists of various behavioural and phenomenological markers that are used as diagnostic criteria. In some cases a single phenomenon (e.g. suspiciousness in paranoid personality disorder) with various manifestations as additional criteria (e.g. suspects others, doubts loyalty, reads hidden meanings) is described, in others a wide range of features are encompassed. For example, borderline personality disorder uses impulsivity, emotional reactivity and cognitive dysregulation as features, with behavioural markers as criteria. Impulsivity is manifested by drug misuse, binge drinking, self-harm, promiscuity and so on. In all, up to 79 diagnostic criteria have to be evaluated in DSM–IV–TR in order to assess the extent of personality disorder in a patient, and these are then grouped into prototypes of the disorders (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007).

Cluster of disorders

In DSM–IV, personality disorder diagnoses are clustered into three groups on the basis of similarity of symptoms (Box 2). Such clustering is not used in ICD–10.

BOX 2 The cluster of personality disorders in DSM–IV

-

• Cluster A: Odd and eccentric – paranoid, schizotypal, schizoid personality disorder

-

• Cluster B: Dramatic, emotional – borderline, antisocial, narcissistic, histrionic personality disorder

-

• Cluster C: Anxious avoidant – anankastic, dependent personality disorder

Cluster A includes odd and eccentric individuals who tend to live in their own internal world and shun human contact as much as possible. Individuals with Cluster B features display dramatic, impulsive and over-emotional behaviour and act in ways that result in unstable relationships with others or even exclusion from their social group. Those with Cluster C features are anxious, seemingly avoidant of others, although they desire and cherish human proximity and feel severe stress when they cannot have the perceived support of others.

Critique of categorical systems

There are major problems with our current nosology – especially with the DSM system, which will be the main focus of the remainder of this article. Establishing diagnoses and clusters in a categorical manner may lead to greater agreement and communication between clinicians (increased reliability), but it does not enhance the fundamental understanding of disorders (no increase in validity).

One of the supposed advances of DSM–III (American Psychiatric Association 1980) was the introduction of the multiaxial system, which separated the newly classified Axis I disorders (which were considered to be transient disorders of state) from Axis II disorders (deemed to be more enduring and dependent on the abnormal traits that the individual possessed). Part of the rationale for this system was that it would force clinicians to consider assessing personality disorder, even in patients with an Axis I condition. By so doing, it was hoped that clinicians would take personality disorder more seriously in their clinical practice and that research into personality disorder would also be promoted (Reference Millon and FrancesMillon 1986). However, many conceptual difficulties remained and have yet to be resolved.

First, the distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders is not borne out by empiricism. This is because the level of comorbidity is so high, especially for some disorders (e.g. borderline personality disorder with depression, antisocial personality disorder with substance misuse), that the distinction is vitiated.

Second, symptoms specific to personality disorders are continuously distributed across both clinical and healthy samples (Reference Livesley, Schroeder and JacksonLivesley 1994). Consequently, diagnostic ‘disorders’ reflect an arbitrary threshold and not true disorders (Reference BlackburnBlackburn 2000).

Third, personality disorder diagnoses often show poor psychometric properties such as validity and reliability (Reference Blais, Benedict and NormanBlais 1998) because current criteria have been selected by clinical consensus rather than empirical analysis (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007). The ICD has a lower threshold for making a diagnosis (Reference Tyrer and JohnsonTyrer 1996) but the DSM, a more rigid system advocating a checklist approach, identifies a higher number of personality disorders: 11 by DSM–IV as opposed to 8 by ICD–10.

Fourth, and related, the diagnoses have limited clinical utility, not helping practitioners to choose between pharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions (Reference Sanderson, Clarkin, Costa and WidigerSanderson 2002; Reference Tyrer and BatemanTyrer 2004).

Fifth, owing to ‘loose’ taxonomic criteria, the nomenclature and number of personality disorders have changed with each new edition of the DSM and ICD, further undermining practitioner confidence. With the revision of DSM–III–R to DSM–IV, some personality disorders (e.g. sadistic and self-defeating) disappeared entirely, whereas others (e.g. passive–aggressive) were removed to the appendix. The disappearance of sadistic personality disorder was largely a consequence of political pressure from feminists who wished to remove what they considered to be a psychiatric loop-hole that might exculpate some extreme (male) offenders (Reference Stone and SkodolStone 1998).

The categorical approach has been popular because it is simple to operate and fits with a medical model of disease, establishing clear boundaries between normal and abnormal functioning. In a social welfare system of democratic governance this is important in terms of resource allocation, prioritising of services and identifying suitable individuals for receipt of interventions. The deficits of the categorical system are probably central to the belief among many clinicians in the UK that personality disorder is not a ‘real’ disorder and that those with personality disorder are so different from people with mental illness that generic mental health services can and should exclude them. Such beliefs and attitudes have led to a crude form of resource allocation within mental health services in the UK that has often tended to ‘reserve’ services for people with chronic and severe forms of psychoses and mood disorders, most often excluding as untreatable those with personality disorder (Department of Health 2003).

The dimensional approach

If the individual, interpersonal and group aspects of personality functioning are emphasised in a diagnostic system, personality will be seen to involve a number of different capacities – dimensions, domains or traits – operating at different times and in different settings. Allport first emphasised the role of ‘traits’ in the makeup of personality as the ‘dynamic organization … of those psychophysical systems that determine characteristics of behaviour and thought’ (Reference AllportAllport 1955). The most influential model of normal personality was proposed by Eysenck. It focuses on the individual's intra-personal characteristics rather than social interactions and describes personality in terms of three dimensions of higher-order traits or ‘superfactors’: psychoticism, extraversion and neuroticism – the PEN model (Reference Eysenck, Pervin and JohnEysenck 1990). A modern extension of this model has five dimensions: neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, openness and conscientiousness – the so-called ‘big five’ or the five-factor model of personality (Reference McCrae and CostaMcCrae 1987). These dimensions can be measured reliably and, with the exception of openness, all the factors have been replicated across cultures and shown to be moderately heritable (Reference Bouchard and LoehlinBouchard 2001).

There is overwhelming empirical support for a dimensional representation of normal personality (Reference Widiger, Frances, Costa and WidigerWidiger 1994; Reference Clark, Livesley and MoreyClark 1997; Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007). Many dimensional or trait models of personality exist but most of these collapse into three (extraversion, neuroticism, psychoticism: Table 1), four (emotional dysregulation, dissocial behaviour, inhibitedness, compulsivity: discussed below) or five (neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, openness and conscientiousness) basic structures.

Personality disorder within a dimensional model of understanding might represent an extreme position on a personality continuum (Reference BlackburnBlackburn 2000). Although this has an intuitive appeal, Reference LivesleyLivesley (2007) has argued that for a disorder to be present, then more is required than an extreme position on a continuum. Instead, he argues that it is the failure to accomplish one or more of certain life tasks that needs to be present for personality to be regarded as disordered. We will return to this when we come to discuss the general features of personality disorder.

Critique of dimensional systems

There are advantages to using a dimensional approach. First, it would fit with other accounts of chronic developmental disorders, which assess both vulnerability and resilience factors, and reframe personality disorder as a disability rather than a disease (Reference FulfordFulford 1989; Reference AdsheadAdshead 2001). Second, it would help to limit the reductionist and rather stigmatising approach to personality disorder, whereby those with the disorder are seen as having a ‘lifelong’ condition that is impervious to change. Third, treatment selection would be informed by existing evidence base: some degrees of disordered personality dimensions will, and clearly do, ameliorate both with time and the appropriate interventions. However, dimensional schemes are simply too complex for everyday use, as substantial knowledge and clinical ability are required to identify the wide range of traits, many of which fall below a threshold for determining abnormality (Reference FirstFirst 2005). When assessment of abnormal personality is required, much time and effort might be spent in assessing the normal aspects while clinically useful constructs such as suspiciousness, insecure attachment, self-harm and narcissism are overlooked.

An integrated diagnostic system for personality disorders

John Livesley has been one of the most influential critics of the current psychiatric nosology and of the DSM in particular. What we find particularly attractive about his suggested revisions is his attempt to integrate into the existing system solutions to many of the criticisms targeted at it. This integration is crucial for two reasons. First, if one were to replace DSM–IV (or ICD–10) with a completely different classificatory system, it would be impossible to draw inferences from research knowledge which is based on the current systems. We would in effect know nothing about the epidemiology of personality disorders, their naturalistic course or their treatment. Second, at a pragmatic level, there would be no reason for the body of practitioners to switch suddenly from one classificatory approach to another, especially as many of the advantages of any new system would be largely theoretical and await empirical verification. Therefore, why would anyone wish to change? Hence, it would be far better to integrate any new system into the existing DSM, as there is too much now invested in the latter to allow its complete replacement.

Here, we provide a brief distillation of the work of John Livesley and his colleagues, but we would strongly recommend the interested reader to refer to their many original contributions (Reference Livesley, Schroeder and JacksonLivesley 1994, Reference Livesley, Jang and Vernon1998, Reference Livesley, Phillips, First and Pincus2003a ,Reference Livesley, Jang, Vernon, Millon, Lerner and Weiner b , Reference Livesley2005, Reference Livesley2007). Although much of Livesley's work focuses on the arguments for a dimensional rather than a categorical classification, this will not be our main focus. Rather, we wish to concentrate on Livesley's general approach and on certain of his crucial changes of emphasis that address many of the criticisms described above.

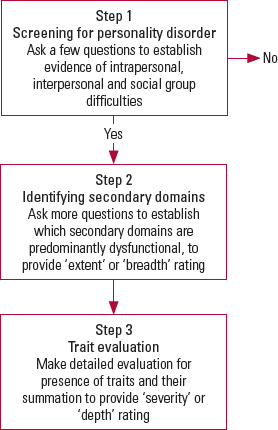

Livesley's work re-directs the clinician to the two-step approach that the DSM recommends – application first of the general criteria (Box 1) and then of the specific criteria – which appears to have been lost in current clinical practice. What happens currently is a ‘bottom-up’ approach: first, individual personality traits are assessed and then these are grouped into the various categorical disorders. In contrast, Livesley recommends a ‘top-down’ approach whereby the first decision to be made is whether the individual has a personality disorder or not. If the answer to this question is in the affirmative, two further tiers of investigation of increasing specificity may be applied if required. The important point is that the process is hierarchical, proceeding from the general to the specific, rather than the other way round. We will now briefly expand on this process, as described by Reference LivesleyLivesley (2007).

A three-step, top-down approach

In defining the general features of personality (and personality disorder), Livesley takes an evolutionary perspective and suggests that there are three life tasks that individuals need to carry out as evidence that they are adapted to their environment. Failure or difficulty in meeting one or more of these tasks is a general sign of personality disorder. The three areas and corresponding potential failures are:

-

• achieving a coherent sense of self (intrapersonal failure)

-

• developing intimacy in interpersonal relationships (interpersonal failure)

-

• behaving prosocially (social group failure).

It is important to recognise that these general features of personality disorder, unlike the secondary domains and primary traits that we shall describe further below, are purely social constructs. Livesley proposes that with a few simple screening questions focused on each of these three ‘general’ areas, it ought to be possible to decide whether or not someone has a personality disorder (Fig. 1, step 1). These questions might be along the lines of ‘Do you have a clear sense of yourself and what you wish to accomplish in your life?’ (the intrapersonal domain); ‘Do you find it difficult either being too close or being very detached from important people in your life, so that relationships are inevitably problematic?’ (the interpersonal domain); ‘Do you find it difficult to conform to the expectations that your family, friends or society at large have of you, so that you are quite often at odds with them?’ (the prosocial domain). It is possible that answers to the last two questions may not be honest, but it is likely that other sources of information (such as key informants or documentary evidence from statutory agencies) may be available to inform one's conclusions.

Proceeding from these general features of personality to the two lower levels in the hierarchy, Livesley commences his discussion of secondary domains by drawing attention to one of the most robust findings in the field of personality disorder. That is, when individual personality traits are subjected to factor analysis, four domains invariably emerge, so that ‘the robustness of the 4 factor model across clinical and nonclinical samples, cultures, and measurement instruments suggests that it reflects the biological organisation of personality’ (Reference Livesley, Jang and VernonLivesley 1998). This is where ‘nature is carved at its joints’, as these four domains of phenotypes are closely correlated to four genetic factors. Indeed, Livesley defines a secondary domain as ‘a cluster of traits influenced by the same general genetic factor’ (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007). Livesley labels these four domains emotional dysregulation, dissocial behaviour, inhibitedness and compulsivity (Table 2). These dimensions correspond to Reference Mulder and JoyceMulder & Joyce's (1997) nomenclature of the four ‘As’ of personality: asthenic, antisocial, asocial and anankastic.

It is important to recognise that some of these higher-order categories/domains comprise entities that encompass a broader array of traits than is implied by the domain name. For instance, Mulder & Joyce's antisocial secondary domain includes not only simple rule-breaking and criminal behaviour but also features of suspiciousness, paranoia and narcissism. The asthenic domain includes not only those with anxious dependent traits but also traits of emotional dysregulation. The asocial domain similarly includes both anxious avoidance and schizoid traits. Finally, the anankastic domain comprises obsessive–compulsive personality traits. We recognise that these four higher-order categories or domains do not map easily onto the three clusters in DSM–IV (Box 2). The antisocial domain, for instance, includes features not only of personality disorders in Cluster B but also of those in Cluster A. The asthenic domain includes features of both Cluster B (emotional dysregulation) and Cluster C (anxious avoidant). The asocial domain comprises traits that occur in both Cluster A (schizoid) and Cluster C (avoidant). Step 2 of the evaluation (Fig. 1) would involve categorising someone with a personality disorder into one (or more) major domain of dysfunctions. This would allow clinical ‘clustering’.

Reference LivesleyLivesley (2007) argues that the four secondary domains are composed in turn of a number of primary traits, which he defines as ‘a cluster of behaviours influenced by the same general and specific factors’. These primary traits are ‘the fundamental building blocks of personality and hence the basic unit for describing and explaining personality disorder’. Through factor and behavioural genetic analysis, Livesley identifies 30 such primary traits, divided unequally between the four secondary domains (Table 2). Step 3 of the evaluation would involve detailed assessment of the particular dysfunctional domain and would provide behavioural and phenomenological markers (Table 3).

Advantages of an integrated system

As already stated, we believe that an integrated classification system such as that offered by the three-step, top-down evaluation model outlined in Fig. 1 meets many of the objections levelled at the DSM system in particular.

First, both the primary traits and the secondary domains are empirically derived and so can be tested with a rigour that is currently impossible.

Second, they make clinical sense, with a focus on the personality traits rather than on behaviour. An obvious example is the antisocial higher-order factor, which includes many traits that are recognised by clinicians, such as ‘suspiciousness’, ‘narcissism’ and ‘hostile dominance’ in the presentation in addition to rule-breaking behaviour and conduct disorder. This moves the description of antisocial personality disorder away from simple criminality to encompass broader features of dissocial personality disorder.

Third, the top-down and hierarchical structure provides the evaluation model with a flexibility in application that current systems lack. For instance, if the question is ‘Does the individual have a personality disorder?’, the answer is provided by screening for three general criteria of personality disorder (i.e. the ability to form an intimate relationship, to act prosocially and to have a sense of identity). If the answer is ‘No’ to any one or more of these criteria, the four secondary domains can be examined with a few further screening questions to discern the predominant features in each (Table 3). It is only when more detailed information is required to identify the specific primary traits that a detailed inquiry has to be made. Even then, Livesley's proposal is parsimonious, as it requires the assessment of only 30 traits, compared with the 79 in DSM–IV–TR: a reduction of 62% (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007).

Fourth, the three-step, top-down model is arguably more comprehensive than the current system, so that fewer individuals are placed in the ‘not otherwise specified’ category, a problem with the current system (Reference Verheul and WidigerVerheul 2004).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, as the four secondary domains differ aetiologically, they should have differing courses and implications for treatment. Detailed consideration of treatment implications is beyond the scope of this article and will not be addressed here.

Implications of an integrated diagnostic system

Severity or ‘depth’ of personality disorders

Notwithstanding the above, empirically based thresholds or cut-offs will be required to identify ‘cases’ and ‘severity’ of disorder for clinical decisions to be binary – ‘to treat or not to treat’. A categorical diagnosis could be made by treating primary traits as equivalent to current diagnostic criteria and applying a severity rating determined by measuring each trait (diagnostic criteria/item) on a 3-point Likert scale, with trait rating summed to provide a dimensional assessment of each disorder. Trait rating should be weighted depending on the contribution that each trait makes to a domain, with higher-level traits given more weight.

A similar strategy exists in psychiatry for diagnostic assessment of intellectual disability: in addition to a continuous-variable distribution of IQ scores, cut-offs exist to separate those with more severe forms of the disorder from those with less severe forms. It is also applied to medical syndromes (e.g. anaemia, hypertension, chronic renal failure), where clinicians place consensual cut-offs separating the pathological from the normal. The thresholds are decided on the basis of clinical experience of the degree of disability implied by scoring above or below the cut-offs. Using such a system for personality disorder, instead of a diagnosis stating that a person does or does not have a personality disorder, they may be considered to have a degree of personality disorder – ranging from personality difficulties to mild, moderate or severe personality disorder.

Extent or ‘breadth’ of personality disorder

A hidden facet of current classificatory systems is that personality disorder diagnoses differ in the ‘breadth and depth’ of the disorder. For example, borderline and antisocial personality disorders encompass a wide range of features, whereas paranoid and obsessive–compulsive personality disorders are little more than single-trait disorders (Reference LivesleyLivesley 2007). A benefit of an integrated approach might be that ‘broader’ personality disorders will ‘trump’ ‘narrower’ personality disorders, for example asthenic ‘trumps’ anankastic, and this will help with the conundrum of multiple diagnoses of personality disorder and of ‘personality disorder not otherwise specified’. Such an approach is already in operation for mental illness diagnoses, where a diagnosis of psychosis often ‘trumps’ other illnesses such as anxiety and mood disorders (Reference Sarkar, Mezey and CohenSarkar 2005).

‘Episodes of personality disorder’

An important consideration that has bedevilled much of the thinking in personality disorder is the immutability that is built into its definition (i.e. that it is lifelong). Increasingly, however, follow-up studies have challenged this proposition (e.g. Reference ParisParis 2003; Reference Skodol, Gunderson and SheaSkodol 2005; Reference Zanarini, Frankenberg and HennenZanarini 2005). Attention has been focused almost exclusively on the course of borderline personality disorder, with these studies (the Zanarini et al study in particular) showing not only that people with borderline personality disorder can lose their traits, but also that if they do so they continue to remain well.

This interpretation has its critics (e.g. Reference WidigerWidiger, 2005), who claim that although some of the superficial features of borderline personality disorder might well disappear (e.g. self-harming behaviour), certain core features remain. This makes sense to us. Thus, people with personality disorder might be thought of as having a continuing underlying diathesis that makes them prone to decompensate if the appropriate triggering events are present. For some, their trait summation might cross an established threshold or cut-off, such that they become ‘personality-disordered’ during a period of heightened stress and then recover. This conceptualisation has the capacity to explain the acquisition of personality disorders in adulthood and diagnostic labels such as ‘disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified’ (DSM–IV) or ‘enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience’ (ICD–10). Taking this to its ultimate conclusion, Tyrer and Bajaj have concluded that there are some individuals who are so vulnerable that only the management of their environment (so that no triggering events occur, or if they do, they only occur very rarely) is necessary for them to remain stable: so-called nidotherapy (Reference Tyrer and BajajTyrer 2005).Footnote †

Clinical prediction and treatment planning

As the four secondary domains represent aetiologically different facets of disorder, each is likely to be associated with a differential course, response to treatment and prognosis. The borderline domain is more responsive to treatment and also has a better long-term outcome without treatment than the other constellations (Reference ParisParis 2003). The secondary-domain dysfunctions provide broad goals that can guide focused targets for treatment, establish collaboratively agreed therapeutic contracts and inform more frequent use of generic strategies. Thus, the asthenic domain will require interventions to regulate affect and to contain thoughts and actions of self-harm as broad treatment goals and develop targeted management strategies. The antisocial domain will require structure and boundaries as broad goals to contain exploitativeness and deception traits, and a focus on sensation-seeking and impulsivity as key treatment targets. The asocial domain will require broad emphasis on promoting safety in attachments, with emotional expression as a treatment target. The anankastic domain will have as its broad treatment goal the capacity to tolerate uncertainty and unpredictability in the patient's ordered world and will use conscientiousness to facilitate engagement in prosocial behaviour.

Harmful dysfunction

One final point to note is the increasing interest in the interplay between genetic vulnerability (as a hard-wired process) and environmental adversity in producing personality disorder in an individual, with the realisation that this is much more complex and fluid than was earlier believed. In this regard, personality disorder is not dissimilar to medical disorders that lead to a wide range of harmful dysfunctional states for the individual and for others. For instance, the new science of epigenetics points the way to a much more complex process than the simple determinism that previously prevailed, so that certain deleterious genes become activated only in the presence of an abnormal environment. This more sophisticated view of gene–environment interaction offers an opportunity to intervene at certain strategic times (Reference Caspi and MoffittCaspi 2006). This will only be achieved, however, if a good nosology provides a firm foundation to direct that process.

Conclusions

There are problems with the diagnosis of personality disorders using current classificatory systems which, in our view, neither an entirely categorical nor an entirely dimensional approach will be able to rectify. We believe that the best way forward is to incorporate aspects of both approaches into the integrated diagnostic system that we have outlined here. The strength of this approach would be to align prototypical data (descriptive behavioural and phenomenological information) with genotypically grounded empirical data. We have adapted Livesley's dimensional approach and revealed how this can explain certain seemingly irreconcilable difficulties within current classificatory systems related to severity of personality disorder, adult onset, the ‘not otherwise specified’ category and multiple comorbidities of personality disorders. It remains to be seen whether the DSM–V and ICD–11 task groups take up these challenges. We are confident that adopting such an approach by the busy clinician will repay the time and effort invested in it.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 With regard to personality disorders, difficulties with current classificatory systems include:

-

a inadequate capture of core personality pathology

-

b good discrimination between different personality disorders

-

c good reliability

-

d clear influence on treatment selection

-

e all of the above.

-

-

2 The categorical approach to diagnosing personality disorders:

-

a adopts a three-component structure

-

b identifies people who also have neurotic disorders

-

c offers a severity rating

-

d is based on psychological foundations in terms of nosology

-

e is adopted by both ICD–10 and DSM–IV.

-

-

3 Personality disorders:

-

a are developmental in origin and relatively inflexible

-

b are not markedly different from cultural norms of thinking, feeling and behaving

-

c can be due to other medical, mental or substance use related disorders

-

d are never maladaptive patterns of relating with others

-

e are episodic in nature and easily managed.

-

-

4 There are:

-

a eleven personality disorder diagnoses in DSM–IV

-

b ten personality disorder diagnoses in ICD–10

-

c lower thresholds for making a diagnosis in the DSM system

-

d higher thresholds for making a diagnosis in the ICD system

-

e many personality disorders, but the total number has remained constant over time.

-

-

5 Dimensional diagnostic systems:

-

a have their origins in medical traditions

-

b do not provide for a range of severity

-

c are meant for everyday use

-

d are favoured by the current international classificatory systems

-

e do not reflect the reality of clinical presentations any better than categorical systems.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | e | 3 | a | 4 | a | 5 | a |

TABLE 1 Tri-dimensional model reflected in most personality theories

| Proponent | Extraversion | Neuroticism | Psychoticism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gray | Behavioural activation Impulsivity Positive affect |

Behavioural inhibition Anxiety Negative affect |

Fight v. flight Aggression |

| Atkinson | Approach motivation Need for achievement Joy of success |

Avoidance motivation Fear of failure Pain of failure |

|

| Barratt | Action orientation | Anxiety | |

| Cloninger | Behavioural activation Novelty-seeking |

Behavioural inhibition Harm avoidance |

Behavioural maintenance Reward dependence |

| Davidson | Approach (Non-)depression |

Avoidance Inhibition Depression |

|

| Depue | Behavioural facilitation Mania Positive emotionality |

Behavioural inhibition | |

| Dollard and Miller | Approach | Avoidance | |

| Eysenck | Extraversion Arousal Positive affect |

Neuroticism Activation Negative affect |

Psychoticism Anger |

| Fowles | Behavioural activation Impulsivity Positive affect |

Behavioural inhibition Aversion |

Non-specific arousal |

| Kagan | Behavioural inhibition | ||

| Newman | Impulsivity Positive affect |

Anxiety Negative affect |

|

| Revelle | Approach Instigation of behaviour |

Avoidance Inhibition of behaviour |

Aggression |

| Simonov | ‘Strong’ type (choleric) v. ‘weak’ type (melancholic) | ||

| Tellegen | Positive affectivity Positive affect |

Negative affectivity Negative affect |

Constraint avoidance |

| Thayer | Energetic arousal | Tense arousal | |

| Watson and Clark | Positive affectivity | Negative affectivity | |

| Zuckerman | Extraversion Positive affect |

Neuroticism | Psychoticism Impulsivity Sensation-seeking Aggression/anger |

TABLE 2 The mapping of Livesley's secondary domains and primary traits and Mulder & Joyce's four ‘As’ of personality

| Livesley | ||

|---|---|---|

| Secondary domain | Associated primary traits | Mulder & Joyce |

| Emotional dysregulation (12 traits) | Anxiousness; emotional reactivity; emotional intensity; pessimistic anhedonia; submissiveness; insecure attachment; social apprehension; oppositional; need for approval; self-harming ideas; cognitive dysregulation; self-harming acts | Asthenic |

| Dissocial behaviour (9 traits) | Narcissism; exploitativeness; sadism; conduct problems; hostile dominance; sensation-seeking; impulsivity; suspiciousness; egocentrism | Antisocial |

| Inhibitedness (7 traits) | Low affiliation; avoidant attachment; attachment need; inhibited sexuality; self-containment; lack of empathy; inhibited emotional expression | Asocial |

| Compulsivity (2 traits) | Orderliness; conscientiousness | Anankastic |

TABLE 3 Recommended evaluation scheme for the foura secondary domains

| Asthenic | Antisocial | Asocial/anankastic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impulses | Alternating high or low | High, with sensation- seeking | Inhibited |

| Affects | Increased intensity, reactivity and instability: range of affects | Increased expression of hostility and suspiciousness | Inhibited emotional expression, unempathic |

| Cognitions | Dysregulated, self-harm ideas | Egocentric and self-aggrandising views, exploitative and rule- breaking ideas | Poor narrator, unexpressive, limited theory of mind |

| Behaviours | Alternating oppositional and submissive, self-harm, chaotic interpersonal relationships | Conduct problems, sadistic | Low affiliation, self-contained, avoidant, orderliness |

FIG 1 A three-step, top-down evaluation model for personality disorder.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.