At the height of the fighting between state security forces and Kurdish militants that followed the collapse of the peace process in Turkey in 2015, a brief public quarrel took place between Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and Sırrı Süreyya Önder, a prominent member of parliament for the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). The spat unfolded over several days as an acrimonious, mass-mediated back-and-forth over responsibility for the ongoing violence in Kurdish cities and the sincerity of each other’s commitment, along with that of their respective parties, to a common political project in Turkey. The exchange began in late December when Önder, together with fellow party members, publicly refused to meet with the prime minister concerning a constitutional reform package while Turkish security forces were still besieging Kurdish cities, trapping thousands of citizens in the cross fire and forcing many more to flee. Önder is reported at the time to have said: “If Prime Minister Davutoğlu’s visit to discuss the constitution is to be meaningful or consequential in any way, the country must be brought back within a constitutional framework beforehand. … I mean, does he expect us to simply abandon the rights of the people living in the war-zone? If he comes to visit us without first recognizing the rights of [the people in the besieged cities] to breathe, to be able to bury their dead, well then, he will drink his kaçak tea and leave [without any agreement].”Footnote 1

The Turkish prime minister responded to Önder’s remarks at a press conference three days later, where he attacked both Önder personally and his party more generally. “Exploding with rage,” as Önder would later characterize him, Davutoğlu launched into a five-minute tirade in which he accused HDP politicians of exhibiting a complete lack of samimiyet ‘sincerity’ and an undignified display of disrespect toward the prime minister as a future guest. Signaling out Önder’s invocation of kaçak tea for special disapproval, finally, the prime minister dismissed Önder as an unserious man who should not have the right to sit in the Turkish parliament. If for Önder and his political constituency, kaçak tea (historically foreign tea smuggled into Turkey, now also a designation for many imported varieties of tea) was a symbol of Kurdish identity, for the prime minister and perhaps a large segment of his political constituency, it was taken as an affront to Turkish nationhood.

In his response to the prime minister at a press conference later that day, Önder picked through the events that had led to the breakdown in peace negotiations, all the while calling into question the prime minister’s understanding of samimiyet as deeply corrupted by its nationalist insistence on the ethnolinguistic and cultural unity of the Turkish nation-state, while affirming his and his party’s sincere commitment to peace, democracy, and coexistence as the fundamental values underlying public life in Turkey. Önder concluded his remarks with a renewed plea for an end to the fighting, while also offering a token of his and his party’s sincerity (in a manner that also happened to highlight the prime minister’s pettiness): asserting that he had never refused to meet but rather had suggested that meeting would be meaningless under the circumstances, Önder offered to serve the prime minister Turkish tea (cultivated around the Black Sea region of Rize) instead of kaçak tea, if only the government would return to the rule of law and the negotiating table: “Peace, right away! Peace, right away! A democratic framework right away! Democratic practice! While there is still time, before it’s too late. … Seriousness, responsibility, political analysis, these are just words, so start with this: come [and meet], and if it’s the kaçak tea that has upset you badly, we will offer you Rize tea, but it’s a matter of life [and death] that we bring our homeland back onto democratic foundations to discuss these issues.”

This article begins by asking how tea has come to possess the capacity to signify competing national and political allegiances, on the one hand, and to invoke a shared moral universal of common values and sentiments, like the values of hospitality and democratic deliberation and consensus, on the other. In tackling this question, the article offers a semiotic analysis of how tea functions as a “medium of value” (Reference TurnerTurner 1968; Reference MunnMunn 1986; Reference GraeberGraeber 2001) in Turkey, highlighting how this value is mediated through linked ideological and material processes that connect and extend across tea’s existence as a drink, a commodity, and a multivalent social sign.

The centrality of tea to Turkey’s public culture became apparent to me during more than a half-decade spent living in Turkey as a student, teacher, and researcher between 2008 and 2019. But it was during eighteen months of study and ethnographic fieldwork with Kurdish-language teachers, students, and activists in and around Mardin province in southeast Turkey between 2015 and 2019 that the politics of tea and the importance of tea as a political sign in Turkey’s Kurdish conflict most forcibly impressed itself on me. Mardin—one of the centers of the 1915 genocide of Anatolian Christian communities and a perennial target of the Turkish state’s anti-Kurdish campaigns over the past century—is a contested space where this contrast in national taste is keenly felt. In drawing a connection between the semiotics of tea and public formation, I describe how the production and circulation of tea, both as a sensuous material object and a sign in social life, are implicated in the organization of publics, or large-scale, mass-mediated political subjects (Reference CodyCody 2011). Such an approach requires an analysis of the semiotic ideologies through which tea mediates the construction of social relationships and is linked to and mobilized in competing public-making projects, as well as the contested and manifold ways that people position and evaluate their own and others’ social identities relative to popular ideologies of national taste.

This article’s objectives are twofold. The first is to better understand the role that tea plays in Turkey as both a materially circulating good and as a medium of value that organizes national publics around historically configured and commonly shared notions of taste. This analysis builds on and synthesizes insights from two intertwined anthropological traditions, semiotic anthropology and the anthropology of value, to better account for the relationship between the political-economic forces that have historically shaped tea’s production and consumption in Turkey with the “semiotic ideologies” (Reference KeaneKeane 2018) that condition its uptake as a moral and political sign in social life. The second objective is to offer a new account of public culture and popular politics in Turkey and North Kurdistan by exploring tea as a corresponding medium of value through which social life is made and evaluated by its participants. On the one hand, it seeks to elaborate the meanings of tea in ideological representations of Turkey’s modern democratic culture. On the other hand, it seeks to better understand how this culture reproduces forms of national difference in which tea now plays both a notable role.

The article is divided into three parts. The first section provides a preliminary sketch of tea’s role in public life in Turkey and offers a brief conceptual overview of how tea’s status as an omnipresent medium of value shapes its uses as a political and moral sign. The second section describes the relatively recent history of tea’s transformation from an exotic and largely unknown product into a near-universally consumed beverage and a prominent token of national identity in both Turkey and Kurdistan over the past century. And it outlines the historical processes through which tea emerged as a symbol for a new democratic culture—defined, inter alia, by a new sense of social proximity and public intimacy (or what in Turkish and Northern Kurmanji Kurdish is called samimiyet)—in which tea became an important medium of both interpersonal sociability and mass solidarity. The third and final section describes how the economic and political pressures exerted by competing nation-building projects in post-Ottoman Anatolia, as well as the forces of the global market, have transformed kaçak tea into both a salient “sign of difference” (Gal and Reference GalIrvine 2019). A central feature of this analysis is a semiotic approach to value that prioritizes the interrelated dimensions of politics, political economy, and public culture and that takes seriously the proposition that the consolidation of material things as social objects, imbued with social values and meanings, is a dialectal, processual and therefore open-ended phenomenon mediated through semiotic ideologies and unfolding within a historically conditioned “representational economy” (Reference KeaneKeane 2003).

Tea as a Medium of Value

According to market researchers, consumers in Turkey drink more tea per capita than anywhere else in the world.Footnote 2 However, tea’s rise to popularity is a recent phenomenon: tea became an object of mass consumption in much of the territory of modern Turkey only between the late nineteenth and the mid–twentieth centuries. Despite its relative novelty, tea has become central to nearly every important form of private and public sociability in the country. The vast majority of people in Turkey drink tea every day—regularly with breakfast and sometimes after lunch and dinner, as well as on many occasions between meals. A ubiquitous and comparably cheap commodity, tea is routinely offered to visitors and guests, given freely to customers and clients in the course of business, and shared among colleagues at the workplace and among friends and family members in the home. More than just inexpensive and ubiquitous, tea is also universal. It transcends class, even as it configures it. It is drunk in the homes of the rich and the poor. It can be found in almost any cafe or restaurant, although its price can fluctuate greatly and thus can serve as a reliable, if one-dimensional, index of the establishment’s position in social space.Footnote 3 Tea also cuts across political, religious, and ethnic divisions. It is drunk by so-called secularists and Islamists, by leftists and fascists, by Kemalists and Kurds, by Alevis and Sunnis. And for the most part, they all prepare and drink it in the same way.

So central is tea to everyday sociability in contemporary Turkey that it can be understood as a generalized medium of value. Tea circulates not only as a popular drink or commodity but as a material and semiotic medium (Reference DouglasDouglas 1987; Reference ManningManning 2012) whose most salient properties are universally recognized, although not uniformly evaluated, across the entire country. Whatever the individual benefit to the drinker (whether from sensuous enjoyment, increased energy, or nutrition), tea’s value is social: it mediates the process through which people make and live social relationships. Tea can be taken as a token of hospitality, affection, or care within the household; a token of friendship in the cafe or coffeehouse; a token of collegiality in the office break room or factory cafeteria; or a token of a shared religious devotion in a Sufi sohbet ‘conversation’. At times, tea is even ascribed with the very qualities of the relationships that it mediates and by extension becomes positioned as an end unto itself. This is seen, importantly, in how tea is sometimes made to serve as a model for social intimacy and solidarity—or what in Turkey is discussed under the rubric of samimiyet—as if tea were the very material embodiment of these values, akin to a synecdoche for sociability (Reference LimbertLimbert 2010, 68).

Beyond its role in everyday sociability, tea has played a notable role in the formation of Turkey’s modern political culture and national identity and is now routinely put forward as a symbol of this culture and identity. Domestically cultivated for close to a century, tea has taken on an outsize place relative to its narrowly economic value in the ideological construction of Turkey’s national market. Following Turkey’s transition toward competitive, multiparty elections and the rapid growth of Turkey’s domestic tea sector following the Second World War, moreover, tea has also become both an instrument and a symbol of democratic politics—a sign mobilized in political discourse and performances that seek to project samimiyet onto a wider, national public. At times, too, tea even serves as a token of Turkey itself.

Upon initial consideration, however, tea may seem an odd candidate to conceptualize as a medium of value. In their shared project to compare such media cross-culturally, for instance, both Graeber (Reference Graeber1996, Reference Graeber2001) and Turner (Reference Turner2008) prefer to compare generalized media of exchange (e.g., beads or money) with those famous anthropological objects in nonmarket societies that are understood to be unique, indivisible, and caught up in the identities of the persons of those between whom they are transferred (e.g., heirloom jewelry made from precious metals, feathers, or shells or performances of chiefly chanting).Footnote 4 Nor is tea especially valuable by the metrics of Turkey’s modern market economy. As one friend from Mardin jokingly put it to me in a conversation on the topic of why Kurds drink so much tea, “Tea is cheap. … After water, it’s tea.” How then can something as commonplace and inexpensive as tea be conceptualized as a medium of value?

When I write of tea as a medium of value, I mean—drawing on Graeber’s (Reference Graeber2001, 75–76) definition—that (1) tea circulates as a concrete material means through which value is realized; (2) tea serves a measure of difference allowing for qualitative distinctions; and (3) tea sometimes becomes positioned as the embodiment or the origin of the values for which it serves as a token. Tea is valuable in the sense that its qualities are realized in productive human action, whether in something like singular acts of market exchange or recurring relations of hospitality. Tea is also valuable in the sense that has become a semiotic medium of representation organizing “collectively institutionalized symbolic model” through which to evaluate social action relative to larger social ends (Reference TurnerTurner 1968).

We observe several of these semiotic properties in a 2018 advertising campaign for Türkiye’nin Ödeme Yöntemi (Turkey’s payment method), or TROY, the country’s first and only domestic payment card scheme launched by the Turkish Interbank Card Center (BKM) in 2016. The campaign was designed to link TROY to a celebration of Turkey’s history, economy and, public culture and, by extension, to position the new card network as more aligned with Turkish values than its major multinational competitors like Visa and Mastercard. Tea played a central role in the campaign, where it was deployed both as a symbol of Turkey and as a more multivalent token of value. One print advertisement from the campaign that ran in several domestic trade journals and magazines, for instance, drew a three-way connection between its new card network, “Turkey’s tea,” and “Turkey’s value” (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Left, graphic recreation of TROY’s original advertisement as photographed by the author in AnadoluJet’s inflight magazine, November 2018. Right, English-language translation. Source: Author’s original drawings.

In both the simplicity of its design and the banality of its symbolism, the advertisement communicates two forms of correspondence: the first between the value of tea as a commodified medium of value and of TROY payment cards as a medium of exchange; and the second between both objects and Turkey, presenting both tea and TROY bank cards as more general tokens of “Turkey’s value.” In linking everyday acts of commodity exchange to a shared life in the Turkish nation-state, the advertisement interpellates its public as “consumer citizens” (Özkan and Reference ÖzkanFoster 2005), seeking to orient their consumer preferences through a project of “nation branding” (Reference DinnieDinnie 2015). This orientation is given expression in the implicit evocation of Turkey’s national market—an evocation that is accomplished here through the union of this new consumer service with a beloved consumer good: tea is a domestically cultivated and processed crop as well as a ubiquitous beverage widely deployed as a token of Turkey. TROY is a new financial service whose relatively small market share and less prestigious branding would benefit, its designers likely hoped, from greater association with this popular national symbol. In buying Turkey’s tea with Turkey’s only domestically controlled card payment system, Turkey’s consumer citizens are invited by the advertisement to imagine that they are buying into the value regime of the Turkish nation-state by supporting Turkey’s economy, celebrating its culture, and thereby participating together with their compatriots as members of a common national public.

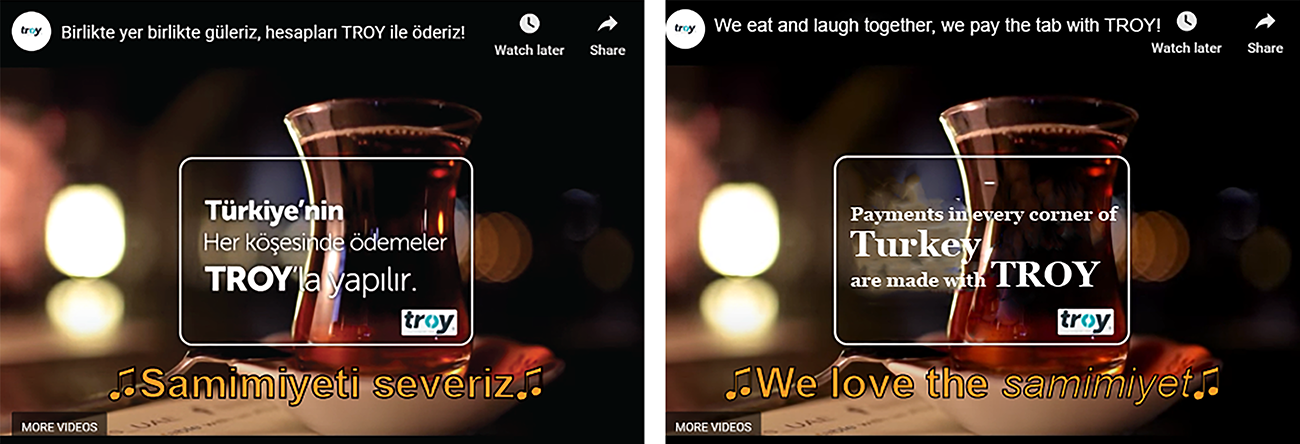

Tea also appeared prominently in a television spot produced for the campaign. The commercial features a jingle accompanied by images of friends and family dining together in public, consumers shopping in upscale cafés and traditional markets with TROY bank cards, and scenic shots from different regions of Turkey (including Rize’s nationally famous tea gardens). It opens with a close-up shot of a glass of tea. As the music begins, a hand is seen dropping a sugar cube into the glass before a graphic of a payment card with the slogan “Payments in every corner of Turkey are made with TROY” is superimposed over the image. Almost simultaneously, a woman’s voice launches into the first line of the campaign’s Turkish jingle: “We love the samimiyet” (Samimiyeti severiz; see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Left, original screenshot of TROY’s television spot. Right, English-language translation of screenshot. The entire video clip can be seen on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ClH9-Y1dAyM.

Samimiyet is often glossed in English as either ‘sincerity’ or ‘intimacy’. However, samimiyet is a more multivalent and commonly deployed social value than either of these English glosses suggest and can communicate nuanced differences in meanings between its popular uses and its deployment in explicitly pious or political discourses. It is a concept, for example, through which people talk about and evaluate their close personal friendships and family life, at school or in the workplace, and in their villages or neighborhoods. In the context of modern Turkish politics, moreover, samimiyet describes horizontal and nontransactional relationships and is used as much to evaluate the integrity of large-scale national societies as interpersonal relationships. Already widely encountered in popular discourses on communal solidarity and Islamic piety, its continuous and increasingly vapid invocation by the government and members of the ruling party over the past two decades has now also conferred upon samimiyet the status of something like official state ideology (Reference BoraBora 2018).

The co-occurrence of auditory (samimiyet) and visual (the tea and the superimposed text) cues in the commercial is therefore likely no coincidence of editing. Rather this temporal contiguity implies a connection made by the advertisers between tea, samimiyet, and Turkey’s national unity—here emblemized by a newly launched national payment system operated by a consortium of Turkish public and private banks (i.e., the BKM) covering “every corner of Turkey.” The TROY advertising campaign thus invites Turkey’s consumers to connect tea to collective life in the nation-state and to see its consumption as a patriotic act of consumer-citizenship signaling membership in a common national public. By extension, it also links life in the national community to everyday forms of face-to-face sociability and the corresponding modes of moral and political evaluation these entail.

A New Drink for a Democratic Society

Wherever I walked around upper Mardin in the run-up to the June 2018 elections, as the fresh air and verdant vistas of spring were giving way to drabber landscapes and the dry, dusty heat of summer, the teahouses in the old city of upper Mardin were showing their political colors. Almost every teahouse was decorated with the flags and posters of the president’s ruling party or the pro-Kurdish opposition—the only two political parties with any substantial level of support in the city—and local politicians, candidates, and their campaign volunteers made frequent, well-publicized stops at the largest and best-known establishments, turning spaces normally difficult to distinguish from one another by passing glance or brief acquaintance into visibly salient sites of political and ethnic differentiation.

Tea’s connection to politics in Turkey is not limited to its presence in public spaces like the teahouse. It also figures centrally in the ritual of the çay ziyareti ‘tea visit’ wherein candidates, party organizers, and volunteers visit potential supporters in their homes—a practice that imitates routine tea visits among friends, family, and neighbors and that also constitutes a practice of grass-roots organizing that proved highly effective in the ruling party’s rise to power two decades ago (Reference WhiteWhite 2004; TuğReference Tuğalal 2009). The symbolism of such practices is not lost on Turkey’s politicians. This is how one local mayor in the province of Samsun and a member of the ruling party, Erdoğan Tok, explained the connection between tea and Turkey’s democracy to journalists after accepting a çay daveti ‘invitation to tea’ at the home of one of his constituents:

[This] is a reality of our culture: we know that the suggestion “Let’s drink a tea” is not only about drinking tea, it’s a suggestion that says, “Come, let’s chat a bit and talk over our troubles.” And so, we chatted with Uncle Hasan in a samimi [characterized by samimiyet] setting accompanied by freshly brewed tea. This is why we are always thinking of citizens when we make investments and when we try to give voice to their feelings. We know that those who truly understand the hearts of our citizens always come to do so through [participating in a] çay sohbeti [conversation over tea].Footnote 5

The politician’s remarks, however platitudinous, provide useful evidence for the social attributes of tea in Turkey under discussion: the drink, still uncommon in many parts of the country a century ago, has now become not only an omnipresent medium of face-to-face sociability but is also widely recognizable as an instrument of democratic politics and, by extension, an important symbol of Turkey’s modern democratic culture. In this ideological constellation, face-to-face consultation and deliberation and intimate familiarity with one’s electoral constituencies or political representatives—the kind of samimi relationship best built over tea—have come to represent an ideal of democratic governance.

An extended account of the history of tea in Turkey is beyond the scope of this article, but a basic familiarity of the main features of this history is required to understand the democratic values that tea now mediates and embodies. Here three points need to be emphasized. First, tea’s introduction as a mass consumer item was shaped by its association with novel social institutions and practices that in themselves reflected and were presented by contemporaries at the time as being emblematic of larger transformations in Ottoman and later Turkish society in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Second, tea’s status as a new, “democratic” beverage was influenced by the way these new social institutions were integrated into the public culture and political economy of postwar Turkey and its transition to multiparty democracy. And third, tea’s emergence as a symbol of Turkey as its modern democratic culture was overdetermined not only by its place in public life (a position it shares in many neighboring countries) but also by state efforts to develop a domestic tea sector in Turkey’s eastern Black Sea region over the twentieth century and, subsequently, the appearance of a new, salient distinction between Turkish and foreign tea.

Tea, that is, a drink brewed from the leaves of Camellia sinensis, was known to some elite elements of Ottoman society as early as the mid–seventeenth century (Reference FaroqhiFaroqhi 2000). Yet tea began to take on the status of a mass consumer good only during the last decades of the empire, when it largely displaced coffee as the primary beverage mediating public sociability and private hospitality alike. The mass consumption of tea began first in neighboring Qajar Iran and the Russian-controlled aucasus over the nineteenth century (Reference MattheeMatthee 1996; Reference FloorFloor 2004). By the start of the twentieth century, tea had become popular across Ottoman Kurdistan and eastern Anatolia as well, and the relatively rapid transition from the coffeehouse to the teahouse as the primary site of public sociability in these regions beginning in the 1890s was accompanied, significantly, by the breakdown of feudal hierachies and tribal identities and the rapid growth in the population of urban and rural proletarians (seasonal workers, informal laborers, sharecroppers) and the formation of a new urban middle class.

In comparison with coffee, the preparation of tea was less labor intensive and more flexible and scalable, making participation in the public life of the teahouse even more accessible than the coffeehouse, whose social functions the teahouse gradually took over and expanded in the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 6 Tea’s relative ease of preparation also made acts of private hospitality more affordable for the masses; whereas prior to tea’s introduction, it was generally only urban notables or village aghas who possessed the resources to host guests in their private residences, tea democratized the capacity for private hospitality, positioning the çay ziyareti ‘tea visit’ as a feature of Turkey’s modern and egalitarian social order.Footnote 7 Finally, tea became widely used in novel Islamic rituals, such as the Sufi sohbet, which was transformed in this period from a devotional practice wherein worshipers primarily sought spiritual and physical proximity to a shaykh to a semipublic forum for religious discussion and guidance and, increasingly, a site of political deliberation and mobilization (Van Reference Van BruinessenBruinessen 2009) in which tea also played in increasingly visible role.Footnote 8

In Turkey as a whole, however, tea did not overtake coffee as the most popular drink until the late 1950s, after substantial state investments by the Democrat Party (DP) in a new domestic tea sector centered on Rize in the eastern Black Sea region (TunçReference Tunçdilekdilek 1961). Tea’s rise in popularity in the major urban centers of western Turkey, consequently, was concurrent with and closely linked in the public imagination, at least initially, to Turkey’s postwar transition to a multiparty democracy—a reality that positioned tea as a new symbol of Turkey’s political culture at the same time that tea was permeating, and in turn changing, established forms of public and private sociability.Footnote 9 The rapid dissemination of tea therefore had important cultural as well as economic effects, positioning the beverage, as Hann (Reference Hann1990, 54) observes, “as a most appropriate symbol of the new society that emerged in Turkey in the second half of the twentieth century”—a status that tea retained even after the 1960 coup and during the political turbulence of subsequent decades.Footnote 10

This is not to suggest that tea is necessarily taken up as a sign of democratic values regardless of how it is deployed. Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erodoğan once frequently integrated tea into his public enactments of his samimi, man-of-the-people persona,Footnote 11 and news media once routinely ran articles and television segments in which the president would casually drop in for tea at the home or small business of ordinary citizens. However, more recently (and more controversially)—as he has become increasingly ensconced behind throngs of security and the walls of his massive new palace in Ankara—Erdoğan has taken to distributing unopened packages of tea instead, sometimes hurling them into the crowd from the stage during rallies or tossing them to supporters from the open door of his campaign bus. In the aftermath of the 2021 wildfires in southern Turkey, videos of Erdoğan throwing tea to diaster victims provoked a pronounced backlash, with opponents of the president decrying it as a cheap gesture that exhibited his lack of concern for and an increasingly out-of-touch attitude toward ordinary citizens.

Nor has tea’s role as a salient political sign been confined to those communities who identify with the Turkish nation-state as a political project or who prefer Turkish-grown tea, as it is encountered across Turkey’s political-consumer spectrum. This was evident, for example, when imprisoned Kurdish politician and then–presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtaş organized a virtual sohbet with his supporters through Twitter under the hashtag #DemirtaşKetılSohbeti (#DemirtaşKettleSohbet) in the immediate run-up to the June 2018 elections. The event had grown out of a political joke. Several weeks earlier, Demirtaş’s campaign staff had organized a similar virtual rally in which they live-tweeted prewritten messages from Demirtaş to his supporters. Turkish prison guards, the campaign’s story goes, fearing that Demirtaş had suddenly acquired some undisclosed means to access the internet, turned over his prison cell searching for contraband, going so far as to disassemble his electric kettle. In the process, they transformed the kettle into a major symbol of his campaign (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Kaçak tea on the menu in front of Kurdish cafes in Beyoğlu, Istanbul. Photographs by author.

In organizing the sohbet ‘kettle’, the campaign drew on both the contingent meaning given to the kettle during the campaign and a more widely circulating ideology that positions the tea sohbet as a paradigmatic democratic practice through which Demirtaş could listen and respond to the concerns of his constituents. The campaign played up the samimi qualities of the sohbet by tweeting printed photographs of supporters’ questions (in the form of preselected tweets) with handwritten responses from Demirtaş designed to elicit an intimate and personal atmosphere. At the same time that the event enacted a widely accessible model of democratic politics, it also played on Demirtaş’s oppositional stance as a Kurdish political prisoner. This stance was figuratively affirmed by Demirtaş himself at the time in an interview with Turkish journalist Cüneyt Özdemir. When Özdemir asked Demirtaş what he prepared in the now famous kettle, the latter responded that he brewed kaçak tea, adding that “it really hits the spot.”Footnote 12

Prior to Demirtaş’s response to the journalist’s question, notably, tea had not been explicitly invoked in the event’s imagery or language, although its implicit evocation was likely already perceived by the campaign’s intended audience, owing to well-established indexical linkages: both the causal chain between heating water (the kettle) and brewing tea and, more significantly, tea’s frequent co-occurrence with the social ritual of sohbet—a connection that partly accounts for tea’s capacity to serve as a symbolic model for sociability and solidarity. As its mobilization by pro-Kurdish politicians makes clear, however, if tea unites everyone in Turkey within a common political and moral cosmology, linking the sharing of tea to modern democratic institutions and their corresponding egalitarian sensibilities, it can also index, and in some cases symbolically stand in for, salient forms of social difference. In describing how kaçak tea emerged as a sign of Kurdish difference in the country and tracing the interlinked ideological and material processes through which this contrast first emerged, it is essential to emphasize both the relative novelty of this contrast and the evolving, contingent character of Kurdish difference in Turkey.

Taste and the National Public

On a chilly evening in late autumn 2018, I sat down for an interview with a former classmate at a Kurdish book café in Ankara, under shelves of Kurdish-language books and amid a milling crowd of students and young professionals gathering for a concert by a Kurdish folk musician to be held later that evening. Melike, my interlocutor, was originally from the border province of Urfa, just west of Mardin, where we had both studied together in Turkey’s first public Kurdish language department until her graduation the previous spring. Melike and her husband had moved to Turkey’s capital for work in Kurdish-language state media, before both were fired in the purge of Kurdish public-sector workers that had followed the collapse of the peace process several years earlier. Out of work, but still wanting to contribute her time and talents to Kurdish-language activism, Melike was a regular presence at the café, giving free Kurdish lessons, mostly to young students in the Kurdish diaspora. As she explained to me what attracted local Kurdish students to the café, running through a list of the café’s most popular cultural and social activities, Melike suddenly grew more animated. “Oh, I have forgotten something! Here they have kaçak tea” (çaya qaçaq in Kurdish), she said laughing:

You know how important that is for Kurds! You know I’ve heard, in fact ask Ms. Z. [the owner of the cafe] because she will be able to tell you even more: some students only come here for kaçak tea. Just think. They only come here for kaçak tea. Kurds love kaçak tea that much. … I also prefer kaçak tea. At home, everywhere. We are just used to it. That’s the tea you drank in your childhood. For example, in my home we drank nothing but kaçak tea. We just can’t drink Turkish tea. No one in my family can.

My own observations have largely confirmed Melike’s assertion: in Mardin and along Turkey’s southern border with Iraq and Syria more widely, kaçak tea is standard in most local homes and teahouses, and domestically grown Turkish tea is generally only available in upscale cafés or national patisserie chains and, even then, often as one of two options. However, kaçak tea’s ubiquity in the region has the secondary effect of reducing its social salience relative to in the rest of Turkey. Whereas a preference for Turkish tea in Mardin is a marked feature of nonlocal identity, a quality associated with civil servants or members of the security forces living temporarily in the province, it is not a major sign of local differentiation: the teahouses in Mardin’s old city displaying pro-government and pro-Kurdish election propaganda, for instance, both primarily serve kaçak tea, and the drink remains the preferred variety of nearly all locals in the province.

If kaçak tea’s social position along the border is so dominant as to be generally unmarked, however, its smaller market share in the rest of Turkey can, in many social spaces, transform into an explicit marker of a nonstandard, minority identity. Outside of Turkey’s Kurdish-majority regions, cafés and coffeehouses are also important spaces where Kurdish counterpublics can enact and validate alternative identities (GüReference Günaynay 2019). In this context, tea serves not only as a medium of internal social cohesion but also as an instrument of external social differentiation—in particular, because one of the identifiable features of many Kurdish cafés or teahouses outside of Kurdistan is that they often, in contrast to most establishments, serve kaçak tea. This has the effect of making kaçak tea a recognized component of café branding, and many teahouses and cafés in western Turkey targeting ethnic Kurdish customers openly advertise on signs and menus that they serve kaçak tea—a promotion that functions, as in the case of the Kurdish book café in Ankara discussed above, both as an appeal to consumer preference and as the interpellation of an ethnic or regional identity (fig. 3).

There are two points to bear in mind here. The first is that whereas the designation kaçak originated as a formal legal distinction between duty-paid and contraband tea—“contraband” still being the primary meaning of kaçak in the context of other goods like electronics or gasoline (Reference OguzOguz 2023)Footnote 13—it has largely evolved in contemporary Turkey into a gustatory distinction between different methods of tea processing and resultant changes in coloring and flavor. The second is that the social meanings of this distinction in taste have changed over time and that, even today, a personal preference for Turkish or kaçak tea does not always neatly correlate with political orientation or ethnic background, even as this preference can be perceived to index, and in some cases is symbolically mobilized to represent, Kurdish identity in Turkey. A semiotic analysis of the material and ideological dimensions of the tea market in Turkey as they have developed historically can help us better understand this phenomenon.

In Turkey today, kaçak tea refers to various varieties of foreign tea processed using the CTC method, in contrast to Turkey’s domestic tea which is processed through the “orthodox” method (Reference HannHann 1990). This means that kaçak tea has a taste and color that is quite distinct from Turkish tea—that is, Türk çayı, Rize, or yerli ‘domestic’ tea, as it is referred to among locals in Mardin.Footnote 14 These gustatory distinctions are mirrored by differences in the respective designs of their packaging and labeling. As kaçak tea—normally labeled as Seylan çayı ‘Ceylon tea’ even when not actually grown in Sri Lanka (a relic of British colonialism that has taken on new significance in modern Turkey)Footnote 15—was historically smuggled to Turkey via wholesalers in Iraq or Syria, it was traditionally marketed under Arabic brand-names with English- and Arabic-language labeling and packaging. This has continued, notably, even after the relative easing of import restrictions beginning in the 1980s. In fact, today a large percentage of the kaçak tea consumed in Turkey is imported legally through Mediterranean ports like İskenderun or Ceyhan and packaged and wholesaled in cities like Gaziantep and Urfa—both border cities and formerly centers for the trade in smuggled goods like tea (YıldıReference Yıldızz 2014). While legally imported kaçak tea often continues to be sold in its customary English- and Arabic-language packaging (often with Turkish-language labels now included as well), this packaging is no longer coincidental to a disequilibrium in economic value created by the interaction between global commodity chains and Turkey’s national tariff regime. Rather, the ongoing use of English- and Arabic-language packaging bespeaks this phenomenon’s objectification in a kind of national “brandedness” (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012), even if, in contrast to Turkish tea, its Kurdish quale (Reference MunnMunn 1986) is never explicitly invoked in its marketing or labeling. Tea’s capacity to signify national difference, however, is quite recent, and until the 1960s the consumption of foreign tea was widespread throughout Turkey and seems to have carried little symbolic value for a Kurdish identity.Footnote 16

Nor did the Turkish state’s early efforts to cultivate a taste for tea among its citizens necessarily result in a preference for Turkish tea. Rather, the dramatic growth in domestic tea production beginning in the 1950s and the rapid transition from coffee to tea drinking over the same decade among consumers in western Turkey also had the secondary effect of actually boosting tea imports: in 1949 Turkey imported just over 1,300 metric tons of processed tea; by 1958 tea imports had risen to nearly 5,200 metrics tons even (TunçReference Tunçdilekdilek 1961). As Hann (Reference Hann1990) outlines, the preference by many of Turkey’s consumers for foreign tea was strengthened by the high cost and low quality of the new domestic product, whose economic viability was only sustained through protectionists policies. Problems with domestic production further intensified in the 1970s following the transfer of responsibility for state supervision from the Ministry of Customs and Monopolies to a newly created public tea corporation, known as Çaykur. This was followed shortly thereafter by the relaxing of quality controls, the expansion of the area under cultivation beyond state guidelines, and the introduction of new harvesting methods (like the use of shears) that increased efficiency but reduced quality over handpicked methods.Footnote 17

The crisis in domestic production in the 1970s resulted in further efforts by the Turkish state to control imports through high tariffs or outright prohibition on commercial imports. The smuggling of tea into eastern Anatolia is probably as old as its status as an object of mass consumption in the region, and already by the 1930s the Turkish state was taking significant steps to secure its border with its southern neighbors, as the Great Depression lowered global agricultural prices and threatened its most important source of foreign currency (ÖReference Öztanztan 2020). However, tea smuggling in particular took on new dimensions in the 1960s and 1970s, as the acquisition of legally imported tea became prohibitively expensive for most people and state actors sought to control, increasingly through outright violence, access to its national market.Footnote 18 Owing to the predominance of Kurdish-speaking communities in Turkey’s eastern border regions, significantly, kaçakçılık ‘smuggling’ had already become closely associated with Kurdish ethnicity in Turkey’s popular imagination, while ongoing state violence against impoverished Kurdish border communities in the name of interdicting the movement of contraband goods became a rallying cry for the Kurdish movement in Turkey (ÖReference Özgenzgen 2003). Among many members of these Kurdish border communities, moreover, kaçakçılık is sometimes presented as a form of antistate resistance (Reference BozcaliBozcali 2020).

While the Turkish state’s securitization of its borders and its increased capacity to enforce a national tariff regime, together with increased subsidies for the domestic tea sector, eventually reduced the relative quantity of smuggled tea consumed into Turkey, this was not in itself sufficient in changing the preferences of Turkish consumers, many of whom continued to prefer foreign-grown tea.Footnote 19 To this end, the state developed new forms of gustatory disciplining that actively sought to link kaçak tea in the public imagination with unhealthy, dangerous, and unpatriotic consumption. By the 1970s, state officials and public figures were openly attacking kaçak tea as not only illegal but unsafe and immoral;Footnote 20 and efforts at gustatory disciplining only expanded in subsequent decades following the liberalization of Turkey’s tea market in 1984 and the beginning of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party’s (PKK) armed insurgency that same year. On the one hand, a new private tea sector made up of both domestic and international players (such as Unilever) joined Çaykur—since 2017 itself a semiprivatized company under the control of Turkey’s Sovereign Wealth Fund—in a common front to preserve the integrity of Turkish tea (and their own shares in the domestic market) against encroachment by foreign competition. Today, Turkish news media, government agencies, and business organizations associated with the tea sector routinely publish material highlighting the damage done by kaçak tea to the national economy and public health alike.Footnote 21

On the other hand, growing violence in the conflict between Turkish state security forces and PKK militants in late 1980s and the 1990s, together with the perception that the Kurdish militant group was directly profiting from the smuggling of tea, lent emotive force to a state discourse linking kaçak tea to criminality and terrorism. This phenomenon was on full display in a broadcast by TRT1 (Turkey’s official state news channel) in 2012 during coverage of a meeting of provincial state and military leaders in the province of Osmaniye close to Turkey’s border with Syria.Footnote 22 At some point during their meeting, the assembled statesmen called upon a passing beverage peddler to serve them tea. As they were being served, Osaminye’s vali ‘provincial governor’, Celalettin Cerrah, asked for confirmation from the peddler that they were to be served Turkish tea. The peddler’s response—whether it was out of a sense of rebellion, honesty, or simple habit is unclearFootnote 23—was that he served both Turkish and kaçak tea, according to his customers’ preferences. The initial reaction from most of the assembled military and state officials, as later confirmed by the Turkish Radio and Television (TRT) narration, was amused laughter. However, Cerrah, moving quickly to regain control of the situation, began to berate both the tea peddler and, through his performance before the assembled cameras, a larger, more amorphous public. “If you’re helping the PKK, then drink kaçak tea,” Cerrah declared, continuing: “If you want to help the PKK, if you want Turkish police and soldiers to be killed, if you want Turkish citizens to be killed, smoke kaçak cigarettes, use kaçak gasoline, what else can I tell you? I mean, could there be such a Turkish citizen? On the one hand, you say ‘Damn the PKK’; on the other hand, you support them. You support them by smoking kaçak cigarettes and by drinking kaçak tea. Wherever I go there is kaçak tea. It just can’t go on like this.”

In his equation of the consumption of kaçak tea with support for the PKK, Cerrah (like the pro-Kurdish politicians discussed earlier) draws an indexical connection between the former beverage and Kurdish identity, even as in this case any explicit mention of such an identity is erased and replaced with vague references to criminality, separatism, and terrorism—a well-described feature of Turkish state discourse (Yeğen Reference Yeğen1999).

The relationship between kaçak tea and the quale of Kurdishness thus operates in multiple dimensions, with the vali’s formulation of the connection unfolding across a distinct vector of indexicality than those animated in the Kurdish book café or by Kurdish politicians. Cerrah does not, like Melike, trace the taste or preference for kaçak tea to common origins and experience of life in the border region through which it was historically smuggled—a kind of geographic contiguity often invoked by friends and informants in Kurdistan—and by further indexical extension, to membership in a common ethnic or national community. Indeed, Cerrah speaks only of Turkish citizens. Instead he points to a causal contiguity based in an alleged relationship of value between the consumer of kaçak tea and the PKK as its alleged primary trafficker, seemingly obvious to the possibility that the tea in question was duty-paid and legally imported.Footnote 24 And Cerrah reframes an economic relationship between buyer and seller as a relationship of support of the former for the latter’s political project (the description of which here, of course, is limited to attempts to kill Turkish soldiers and divide the country).

Yet even the ideological metrics that position kaçak tea as an affront to the integrity and honor of the Turkish nation-state—an instance of “semiotic transgression” (Theng and Reference ThengLee 2022)—can themselves be taken up and redeployed by Kurdish actors in a way that serves, through a mode of comedic ridicule akin to “stereotype inversion” (BermúReference Bermúdezdez 2020), to subvert these metrics. Thus, for instance, did a recent Kurdish-language comic strip poke fun at the absurdity of the exaggerated offense taken by many in Turkey at the mere existence of kaçak tea (fig. 4). The comic’s first frame depicts a personified, seemingly self-satisfied glass of tea. The tea is identifiable as stereotypically Turkish owing to its service in a traditional tulip shape glass accompanied with a red and white saucer (Turkey’s national colors) and is ironically labeled in Kurdish as “an honorable tea.”Footnote 25 The second frame depicts the same glass of tea, now seemingly outraged by the arrival of a second tea whom the former glass insults as a qehpo ‘(male) prostitute’. This second tea, in contrast, comes in a paper cup (a comparatively déclassé mode of drinking tea) and with a tea bag labeled “Mahmood Tea”—a popular brand of kaçak tea. While labeled “a dishonorable tea,” moreover, it remains cool and seemingly unbothered by the insult or the judgment of the Turkish tea—a kind of self-deprecation whose effect is group affirmation.

Figure 4. A Kurdish-language cartoon contrasting Turkish and kaçak tea that originally appeared on the Hestucomics Instagram page and was drawn by Ronî Battê. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

If kaçak tea can be mobilized as a symbol of Kurdish identity, it does so within a dynamic “indexical order” (Reference SilversteinSilverstein 2003) in which its precise meanings are contingent on framing and context and remain subject to renegotiation. In 2020, for example, Çaykur launched a new brand of domestic tea named “Mezopotamya Çayı” ‘Mesopotamia tea’ that explicitly targets consumers in east and southeast Turkey. In its method of processing, the brand seeks to mimic the look and taste of Ceylon (i.e., kaçak) tea, while its name plays on recognized associations between kaçak tea and Turkey’s southeastern border region, since Mesopotamia functions both a coded designation for Kurdistan and a contested geographic designation for multiethnic regions like Mardin province. Introduced in a conscious effort to encourage the consumption of Turkish over foreign tea, the brand plays upon kaçak tea’s status a sign of social difference at the same time that it seeks to assimilate this difference and capture its value for the domestic market. If successful, this effort promises not only to reduce the share of foreign tea consumed in the regions but also to recreate—in a process of “fractal recursion” (Gal and Reference GalIrvine 2019)—the distinction between “Kurdish” and “Turkish” tea within the domestic sector.Footnote 26

Conclusion

In this article I have shown how tea functions as a medium of value in contemporary Turkey, paying close attention to how its status as a popular drink and domestically cultivated commodity shape its uses as an ethical and political sign and its role in the formation of competing national publics within Turkey’s modern borders. In describing tea’s role in public formation, I focused analytical attention on the value relations aligning people and ideologies of taste with the nation as a larger horizon a value—an end toward which other activities, like sharing a glass of tea (or sharing a cartoon about tea on social media) can be socially oriented. Concurrently, I examined the historical connection between tea and modern ideologies of democracy and nationhood in the country, paying special attention to the ways that tea is connected to samimiyet as a social value with intertwined ethical and political meanings; and I considered what kaçak tea’s mobilization as a political sign in the context of Kurdish politics in Turkey can reveal about the semiotic dimensions of Kurdish difference in the country. More broadly, I have tried to show how things, in becoming social objects, likewise become semiotic media of value whose contingent properties, when examined as such, allow us to elaborate on their social histories and better understand their social meanings.