Introduction

The Small Cycladic Islands Project (SCIP—also EKYNH: το πρόγραμμα Έρɛυνας Kυκλαδικών Nησίδων) is a new archaeological survey targeting the very smallest of the Aegean Islands. As a collaboration between the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, the Norwegian Institute at Athens and Carleton College (directed by Athanasoulis, Knodell and Tankosić), this project is undertaking surveys of several uninhabited islands in the central, northern and western Cyclades. The SCIP aims to gain a better understanding of the role of small, uninhabited islands in the long-term history of the Aegean. While all target islands are currently uninhabited, such places would have played a variety of roles at different points in the past, including as stepping stones, cemeteries, maritime strongholds, sanctuaries, pirate hideaways or goat islands. Offshore islets functioned also as extensions or satellites of larger islands, and at times were the subject of competing territorial claims. In 2019 and 2020, the SCIP carried out intensive archaeological surveys of 21 small islands around Paros and Antiparos using a variety of multi-disciplinary techniques (Figure 1). A recently published report on the 2019 field season, which focused on ten islets around Paros, provides a detailed discussion of the background, context and initial results of the project (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020). The present article updates and expands upon that publication through the addition of the 2020 results.

Figure 1. Location map showing the islands surveyed and places mentioned in the text (map by A. Knodell).

Methods

There are long traditions of survey and island archaeology in the Aegean (e.g. Bevan & Conolly Reference Bevan and Conolly2013). The SCIP's contribution is to narrow the territorial remit of an individual island survey and to expand the conceptual and comparative scope (see also Galanidou Reference Galanidou, Carver, Gaydarska and Montón-Subías2015). Each island in the study area was the subject of a comprehensive survey, which in most cases was carried out in one to two days, consisting of fieldwalking, artefact collection, feature documentation and site-based gridded survey. Fieldwalking involved a team of five surveyors at ten-metre spacing systematically walking through the landscape, divided into survey units, counting and collecting artefacts (Figure 2). We also mapped, drew and photographed archaeological features and recorded detailed notes on the natural environment of each island. Areas of particular interest were singled out for gridded collection in 10 × 10m grid squares and for 3D recording with a combination of aerial and terrestrial photogrammetry.

Figure 2. Fieldwalking on Panteronisi (photograph by A. Knodell).

Results of the comparative island survey

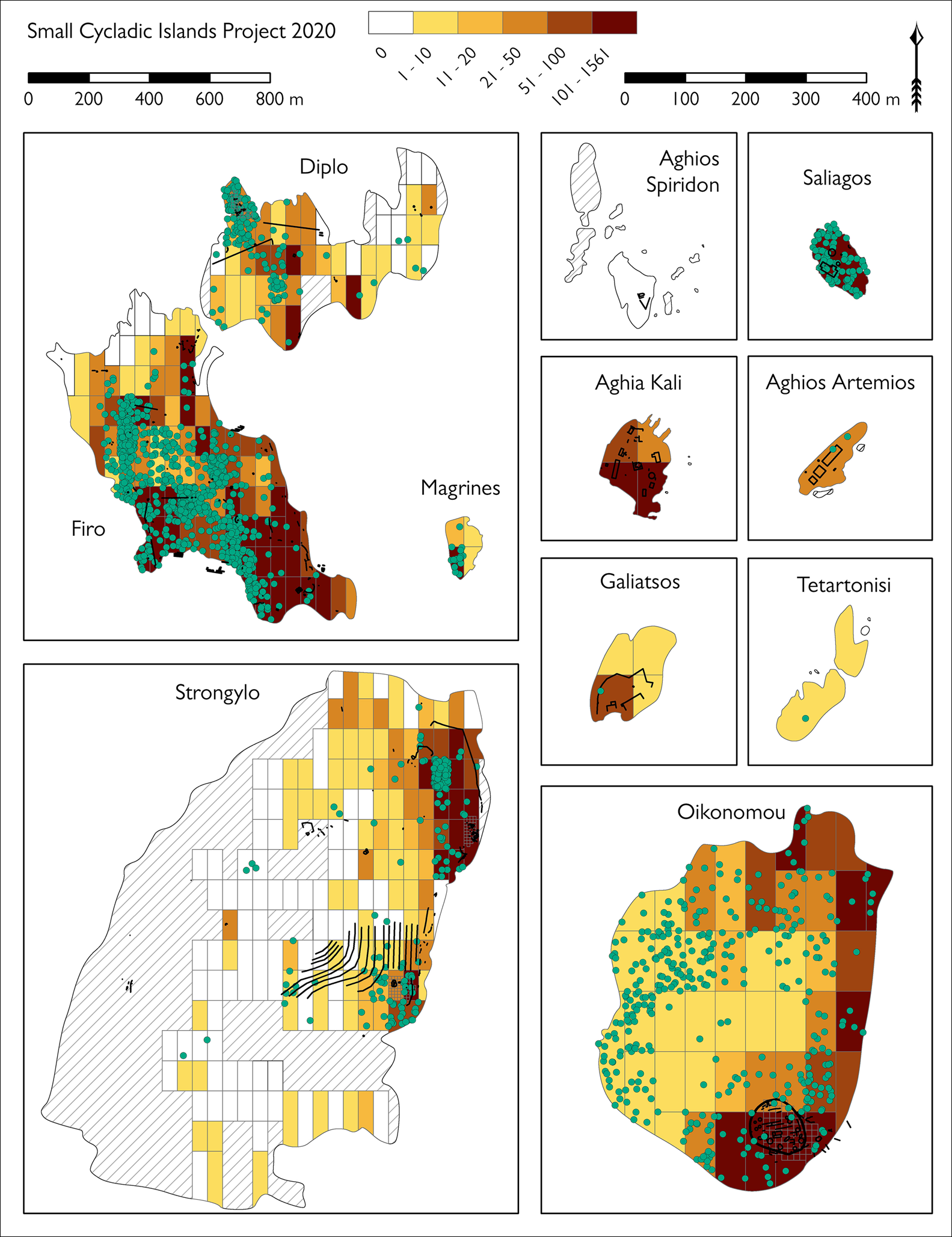

In 2019 and 2020 the SCIP surveyed nearly all of the small islands surrounding Paros and Antiparos (21 in total; Figures 3–4). Dryonisi was paradigmatic of the project as a whole, with remains of several, non-continuous periods of use. An Early Bronze Age settlement and a quarry site in use during Classical and Late Roman times signal various types of engagement with this landscape at different junctures.

Figure 3. Composite map of the islands surveyed in 2019, showing relative sizes, survey units, gridded collection units (grey squares) and archaeological features (black lines), along with pottery counted in each survey unit (in yellow to brown gradation) and lithic findspots (green dots) (map by A. Knodell).

Figure 4. Composite map of the islands surveyed in 2020, showing relative sizes, survey units, gridded collection units (grey squares) and archaeological features (black lines), along with pottery counted in each survey unit (in yellow to brown gradation) and lithic findspots (green dots); note the different scales on the left and right columns (map by A. Knodell).

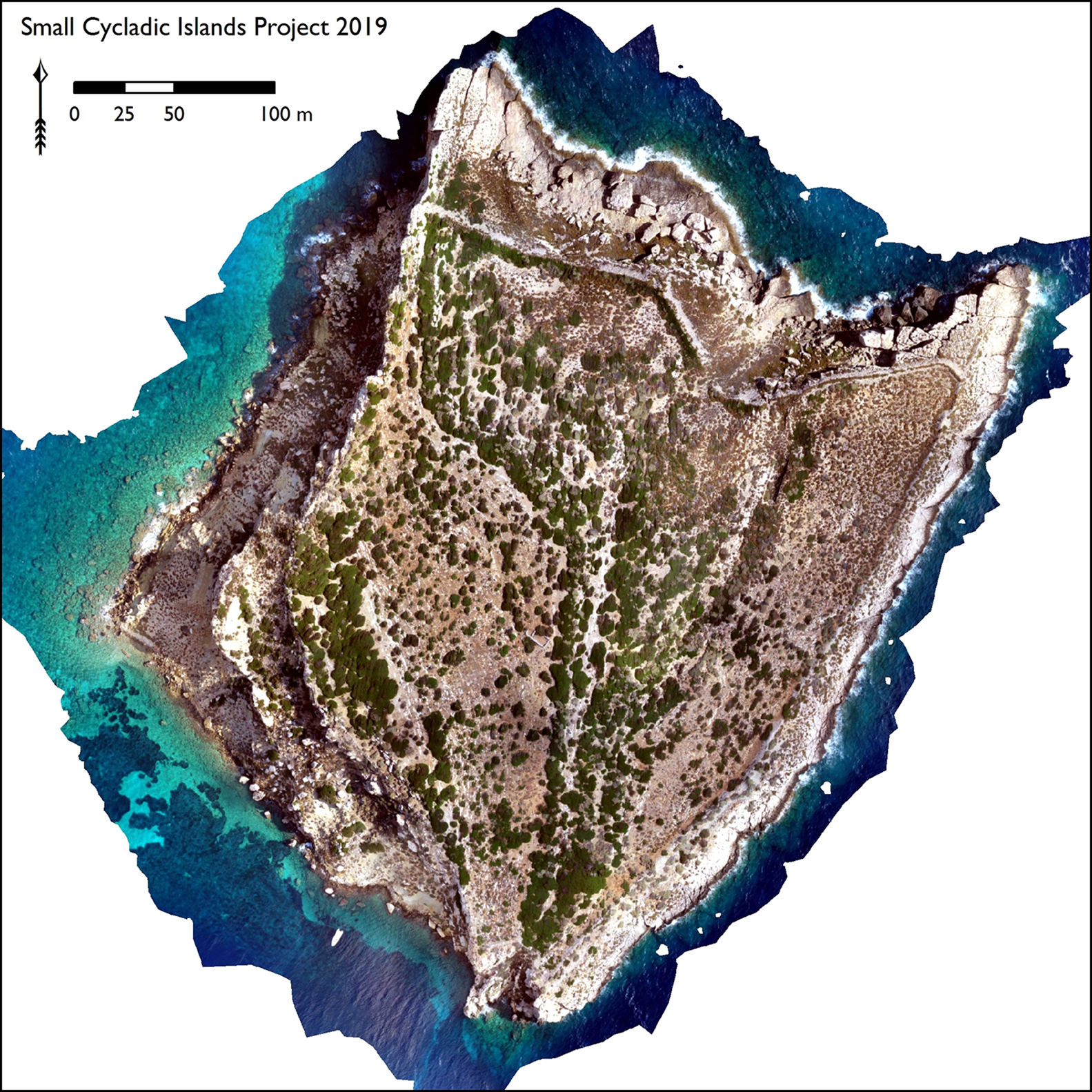

Vriokastro (also called Evriokastro, Evraiokastro and Viokastro), Gaidouronisi and Filizi are located north-east of Paros. Earlier surveys focused on the island of Paros had documented architecture and artefactual material on Vriokastro and Filizi. The more detailed work carried out by the SCIP, however, led to several new discoveries. First, we were able to document the impressive Byzantine fortification of Vriokastro in new detail through a combination of drone-based photogrammetry and terrestrial survey (Figure 5). At Filizi the combination of detailed architectural mapping and gridded surface collection now suggests that this site was one of the most important of the settlements surrounding the Bay of Naousa during the Geometric and Archaic periods.

Figure 5. Vriokastro orthophotographic model (orthophotograph by E. Levine, D. Nenova, & H. Öztürk).

Work continued in 2020 around the Bay of Naousa, where Oikonomou was home to a small, enigmatic Archaic to Classical site, delimited by a monumental polygonal wall (Schilardi Reference Schilardi1975). Later material is also present, especially from Roman to Byzantine times, raising questions about the chronology of some of the architecture. An entirely different pattern is represented on the islets of Aghia Kali, Aghios Artemios and Galiatsos, which housed major installations of the Russian occupation of the Bay of Naousa (1770–1774) during the Russo-Turkish War.

The islets between Paros and Antiparos show a quite different pattern. Artefact counts on Panteronisi, Tigani, Glaropounta, Mikronisi, Tourna and Kampana were quite low, although Tigani has an impressive sandstone quarry and pottery from Geometric and Late Roman times. Shepherding installations on several of these islets and small churches on Kampana and Aghios Spiridon signal different types of engagement with these islandscapes—both subsistence-based and spiritual—which continue to this day.

Also in the Antiparos-Paros strait is the Neolithic site of Saliagos, located on the smallest islet in the survey area (Evans & Renfrew Reference Evans and Renfrew1968). A brief survey of the islet in 2020 puts it in dialogue with the broader results of the SCIP and complements the earlier work with new methods (Figure 6). Firo and Diplo revealed rich ceramic and lithic assemblages from a variety of periods, including significant sites of Neolithic to Early Bronze Age date (on Diplo) and Archaic to Hellenistic and Roman dates (on Firo) (see also Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou and Triantafyllidis2017). It is noteworthy that at times these islets would have been attached to Antiparos, and in some cases also to Paros, especially in prehistory.

Figure 6. Aerial photograph of Saliagos, facing south (photograph by H. Indgjerd).

Finally, Strongylo exhibits multiple periods of use, with substantial concentrations of Early Bronze Age, Classical to Hellenistic and Roman to Byzantine pottery, with more incidental activity in between and after. The main features are a Hellenistic tower on the summit of the island and a complex of early modern installations containing several spoliated ancient blocks, located at the site of an historically attested church.

Diachronic trends of incidental occupation

After the 2019 field season we could already draw several preliminary conclusions from this work (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020), which we can supplement as follows. (1) Patterns of occupation or use on these islands are limited to particular periods, which are not consistent across different islands; continuous occupation across several time periods rarely happened in these places. (2) The pattern of use of small islets is inevitably linked to available resources; access to water is important, as is viable agricultural land (on Firo), pasturage (Panteronisi, Tigani, Mikronisi, and Strongylo) and mineral resources (stone quarries on Dryonisi and Tigani). (3) Isolation and connectivity are both significant in different situations. For example, the accessibility of Dryonisi was important for Early Bronze Age habitation and Late Roman mineral exploitation; Vriokastro, however, is extremely difficult to reach, being heavily fortified and with no natural harbour anywhere on the island. The physical insularity of these places also varies over time, especially in the north of Antiparos and in the Paros-Antiparos strait. (4) Systematic methods of team-based, intensive survey have much to offer in small islands, especially when applied in a comparative fashion. While certain of these islands had been documented before, a wealth of new information was revealed through more detailed survey, artefact collection and study. As we move forward, the results of this research will be examined in light of previous and ongoing research, especially by the ephorate, for example, concerning the ‘satellite’ and ‘metropolitan’ relationship of Despotiko and Paros during the Late Roman period (Athanasoulis & Diamanti Reference Athanasoulis, Diamanti and Katsonopoulou2019; Diamanti et al. Reference Diamanti, Kourayos and Lamprakis2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Eleni Kalavria, Jorunn Økland and Delia Tzortzaki for their administrative support. We are especially grateful to the members of the 2019 and 2020 field teams: Sue Alcock, James Brown, John Cherry, Alex Claman, Liza Davis, M.J. Fielder-Jellsey, Aaron Forman, Thanasis Garonis, Ioannis Georganas, Magda Giannakopoulou, Nikos Gkiokas, Heinrich Hall, Hallvard Indgjerd, Aikaterini Kanatselou, Evan Levine, Rebecca Levitan, Fanis Mavridis, Denitsa Nenova, Hüseyin Öztürk, Nasia Papadimitriou, Vaia Papazikou, Aubrey Rawles, Charles Sturge and Sam Wege. Finally, our thanks go to the residents of Piso Livadi, Aghios Georgios and Antiparos Town for their hospitality, as well as to the guards of the Paros Archaeological Museum.

Funding statement

Funding was provided by an Archaeological Institute of America-National Endowment for the Humanities Grant, the Loeb Classical Library Foundation, Carleton College, the Institute for Aegean Prehistory and the Norwegian Institute at Athens.