Leading an active life during adolescence may have a positive influence on chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, CVD and some types of cancer later in life(Reference Malina1). Current public health guidelines recommend that adolescents should engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity for at least 60 min every day(2). This amount of physical activity seems to be necessary to achieve beneficial effects on health in adolescence(2), but most epidemiological studies have shown that adolescents do not meet the physical activity recommendations(Reference Troiano, Berrigan and Dodd3, Reference Martinez-Gomez, Ruiz and Ortega4). Adolescents have numerous opportunities during the school day to engage in physical activity and a daily routine involving active commuting to school may be a good opportunity to accumulate physical activity at the recommended intensity.

Active commuting has also been associated with a reduction in obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in adults(Reference Hamer and Chida5). Although there is some contradictory evidence, several studies have shown that adolescents who actively commute to school also might have higher levels of physical activity and fitness, as well as lower levels of body fat(Reference Davison, Werder and Lawson6). In addition, active commuters to school in adolescence might become active commuters in adulthood (i.e. walking or cycling to work). Consequently, educational and public health organizations are showing increasing interest in joint efforts to promote active commuting to school.

A number of studies over the last decade have examined possible correlates of active commuting to school in children and adolescents. Overall, potential key factors such as neighbourhood, environmental, demographic, school, family, physical and social characteristics have been investigated in order to develop strategies to increase the number of students walking or cycling to school(Reference Davison, Werder and Lawson6). However, limited research has shown potential behavioural factors that may predict active commuting to school. In contrast with children, adolescents make their own decisions regarding daily behaviour; therefore a better understanding of the behavioural correlates of active commuting to school in adolescence is required. The purpose of the present study was therefore to examine behavioural correlates of active commuting to school in Spanish adolescents.

Methods

Study design and participants

Participants for the present study were those enrolled in the AFINOS (Physical Activity as a Preventive Measure Against Overweight, Obesity, Infections, Allergies, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Adolescents) cross-sectional study between 2007 and 2008. The AFINOS study design, protocols and methodologies have been described in detail elsewhere(Reference Veiga, Gómez-Martínez and Martínez-Gómez7). Briefly, the AFINOS study was designed to assess health status and lifestyle factors through a survey completed by a representative sample of adolescents, aged 13 to 17 years, from the Madrid region(Reference Veiga, Gómez-Martínez and Martínez-Gómez7). Secondary schools were randomly selected according to the geographic distribution of adolescents in the region. The sample size was calculated taking 0·05 as the maximum permissible error (reliability of 95 %) and based on an estimated prevalence of overweight and obese adolescents of 20 %. The final calculated sample size (1998 adolescents) was increased by 20 % to allow for possible dropouts or data losses to give a final sample size of 2400 participants of both genders. Of these subjects, 2029 (979 boys and 1050 girls) who provided valid data on their mode and time of commuting to school were included in the current study.

All parents/guardians and adolescents gave their written informed consent for participation. The AFINOS study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Puerta de Hierro Hospital (Madrid, Spain) and the Bioethics Committee of the Spanish National Research Council.

Socio-economic and demographic factors

Some socio-economic factors were obtained using self-report questions designed for adolescents(Reference Veiga, Gómez-Martínez and Martínez-Gómez7). Family structure was determined by asking adolescents whether their mother and father lived at home with them. The final variable used was having both parents at home or another option (i.e. mother or father or neither at home). An immigrant status (yes/no) according to country of birth was also identified. Adolescents reported the number of brothers/sisters in their family and, in accordance with Spanish government criteria, large families were defined as those with at least three children. The type of school was categorized on the basis of being administered by the national government (public schools) or not (private schools). The demographic distribution in the Madrid region was categorized into two categories, with the metropolitan area (Madrid city) and suburbs being merged into a single category and the group of outlying towns forming the other category.

Assessment of commuting to school

Mode and duration of commuting to school were self-reported using standardized questions for Spanish adolescents(Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz8). Adolescents reported their habitual mode of transportation to school in the following categories: (i) walking; (ii) cycling; (iii) bus/subway; (iv) car; or (v) motorcycle. The active commuting to school group consisted of those adolescents who walked or cycled to school. Responses regarding duration of their habitual commuting to school were categorized as follows: (i) 15 min or less; (ii) 15 to 30 min; (iii) 30 to 60 min; or (iv) 60 min or more.

Behavioural factors

Several lifestyle factors were selected from the epidemiological questionnaire for adolescents(Reference Veiga, Gómez-Martínez and Martínez-Gómez7). Overall physical activity was assessed using the validated Spanish version of the PACE+ (Physician-based Assessment and Counselling for Exercise) questionnaire for adolescents(Reference Martínez-Gómez, Martínez-De-Haro and Del-Campo9). This questionnaire uses two questions to assess physical activity: (i) ‘Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day?’ (Q1); and (ii) ‘Over a typical or usual week, on how many days are you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day?’ (Q2). Both questions have a scale of 0 to 7 d. Adolescents were classified into two groups (active/inactive) according to the PACE+ criterion that considers physically active adolescents as those who engaged in physical activity on at least 5 d/week using the mean of both questions(Reference Prochaska, Sallis and Long10). For differentiating among types of physical activity, participation (yes/no) in extracurricular physical activity was determined by the following question: ‘Do you undertake any physical sporting activity after school?’

Adolescents were also asked to self-report how much time they usually spent watching television, reading as a hobby, and sleeping at night on normal school days. For these behaviours, participants were also classified into two groups and healthy behaviours were considered as follows: watching television for less than 2 h/d(11); reading for at least 1 h/d; and sleeping at night for at least 8 h/d(12). Adolescents’ dietary habits of recommended fruit intake (at least two servings daily) and skipping breakfast (yes/no) were also identified by self-report(Reference González-Gross, Gómez-Lorente and Valtueña13). Finally, patterns of habitual smoking and alcohol intake were reported.

Data analysis

Study sample characteristics are presented as number of subjects and percentage, unless otherwise stated. The χ 2 test was performed to obtain inter-group differences according to socio-economic and demographic characteristics. Binary logistic regression analyses were applied to examine the associations between behavioural factors and active commuting to school. Behavioural factors were introduced separately. Interaction factors (gender × main exposures) were incorporated into the models to determine whether gender modified the associations between behavioural factors and active commuting to school. Since no significant interactions were found (P > 0·1), analyses were performed with adolescent boys and girls together. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated for all associations using three additive models. The first model showed crude OR, whereas the second model showed multivariate-adjusted OR controlling for age, gender, socio-economic factors (family structure, family size, immigrant condition, type of school) and demographic distribution. The final full-adjusted model included the above confounder variables as well as those behaviours that showed significant associations. This final model examined whether the associations between behavioural factors and active commuting to school are independent of each other. In the logistic regression models, adolescents with unhealthy behaviours were considered the reference group. Analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows statistical software package version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and the significance level was P < 0·05.

Results

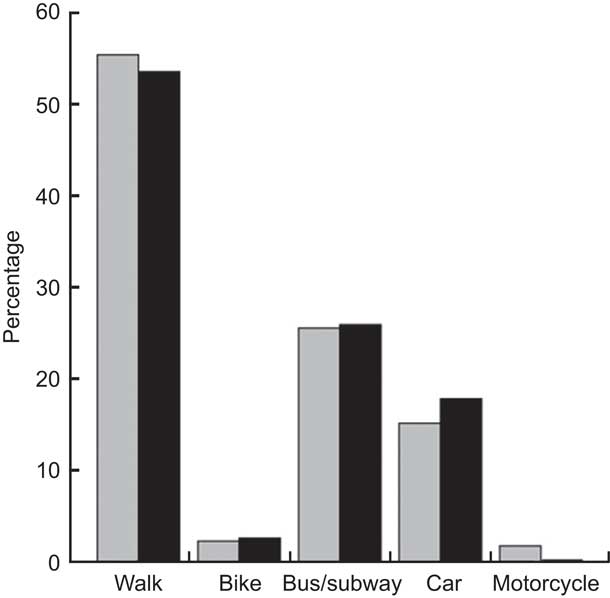

All adolescents (n 2029) provided a complete set of data regarding socio-economic and demographic factors, whereas data on behavioural factors were not available in several cases (range, n 1857–1993). The samples with missing data were equivalent to the whole sample according to age and gender distribution (P > 0·05). Descriptive patterns of commuting to school are presented in Fig. 1. Overall, walking was the most common mode of active commuting to school (55·4 % of boys and 53·5 % of girls), whereas bus/subway was the most common inactive mode (25·5 % of boys and 25·9 % of girls). Similar numbers of adolescent boys (57·6 %) and girls (56·1 %) were classified as active commuters to school (P = 0·491), and the duration of these active journeys was usually 15 min or less (80·0 % of boys and 77·1 % of girls). In addition, there were no significant differences in levels of active commuting to school by age in either boys (P = 0·059) or girls (P = 0·080).

Fig. 1 Mode of commuting to school by gender (![]() , males;

, males; ![]() , females) among adolescents (n 2029) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

, females) among adolescents (n 2029) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

Table 1 shows differences in active commuting to school according to socio-economic factors and demographic distribution groups in the total sample and by gender. A higher percentage of adolescent boys in families with both parents living at home reported active commuting to school (P = 0·015), although there were no differences between family structure groups in girls (P = 0·971). There were also no inter-group differences in levels of active commuting to school according to other socio-economic factors, such as family size, immigrant condition and type of school. However, a lower percentage of adolescents in the metropolitan area and suburbs were classified as active commuters to school compared with those adolescents living in towns (52·0 % v. 73·6 % respectively, P < 0·001). These differences were similar when analysed separately by gender (both P < 0·001).

Table 1 Prevalence of active commuting to school according to socio-economic and demographic factors among adolescents (n 2029) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

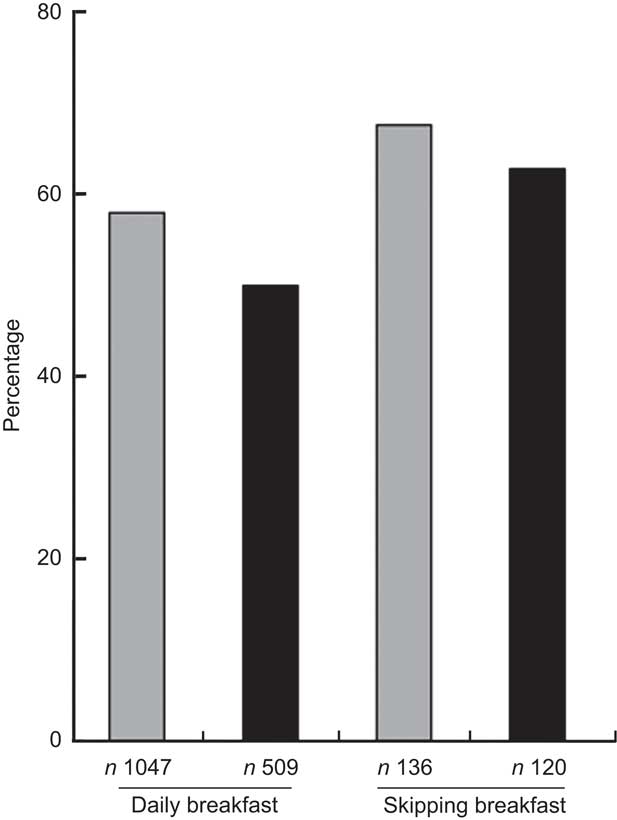

Table 2 presents the associations between behavioural factors and active commuting to school. The binary logistic regression showed that overall physical activity, extracurricular physical activity, watching television, reading as a hobby, fruit intake, smoking and alcohol intake were not significantly associated with active commuting to school, whereas adequate sleep on school days (OR = 1·386, 95 % CI 1·144, 1·680; P = 0·001) and habitual breakfast (OR = 0·745, 95 % CI 0·574, 0·966; P = 0·027) were positively and inversely associated with active commuting to school, respectively. These associations remained after controlling for age, gender, socio-economic factors and demographic distribution (Table 2). A final model including confounder variables and both behavioural factors was tested (n 1812). This analysis showed that sleep duration (OR = 1·354, 95 % CI 1·107, 1·655; P = 0·003) and habitual breakfast (OR = 0·657, 95 % CI 0·494, 0·874; P = 0·004) were independently associated with active commuting to school. Hence, adolescents with inadequate sleep duration on school days and habitual breakfast consumption reported the lowest percentage of active commuting to school (Fig. 2). The final model was also performed separately for those adolescents who cycled to school (2·3 %). These analyses showed that habitual breakfast was also inversely associated with commuting to school by bike (OR = 0·071, 95 % CI 0·035, 0·147; P < 0·001), while adequate sleep duration was positively associated with cycling to school (OR = 4·357, 95 % 1·867, 10·170; P = 0·001).

Table 2 Associations between behavioural factors and active commuting to school among adolescents (n 1857 to 1993) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

Fig. 2 Prevalence of active commuting to school across sleep (![]() , adequate sleep duration;

, adequate sleep duration; ![]() , inadequate sleep duration) and breakfast groups among adolescents (n 1812) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

, inadequate sleep duration) and breakfast groups among adolescents (n 1812) aged 13–17 years, Madrid, Spain

All analyses were also repeated in younger and older groups (13·00–15·49 and 15·50–17·99 years) and the results did not change materially (data not shown).

Discussion

The main results of the present study indicated that, of all lifestyle behaviours analysed, only those behaviours that occur immediately before commuting to school were important correlates of active commuting to school, irrespective of socio-economic and demographic factors. In particular, adequate sleep duration on school days was positively associated with active commuting to school, whereas, somewhat unexpectedly, adolescents who eat breakfast had a lower prevalence of active commuting to school. Since behavioural correlates of active commuting to school are generally unknown, these novel findings should be taken into consideration when developing public health strategies that promote active modes of commuting to school among adolescents.

No previous studies have aimed to examine the influence of sleep duration on a school day on active commuting to school. Sleep duration is considered a relevant health behaviour in both adolescents and adults because of its link with numerous chronic diseases(Reference Van Cauter and Knutson14–Reference Gallicchio and Kalesan16). In addition, our study suggests that adolescents who sleep enough hours at night according to the public health recommendation for these ages(12) are likely to commute actively to school. Several previous studies that examined the associations between sleep duration and daily physical activity in adolescents reported contradictory findings and, overall, did not support a plausible cause-and-effect relationship(Reference Wells, Hallal and Reichert17–Reference Van den Bulck19). Morning fatigue may mediate our significant association between sleep duration and active commuting to school(Reference Van den Bulck19). Accordingly, adolescents with insufficient sleep duration might experience morning fatigue and therefore might choose inactive modes of commuting to school rather than active modes(Reference Ortega, Chillón and Ruiz20). However, these observations cannot be elucidated from the current study and further research is therefore necessary to better understand the link between sleep duration and active commuting to school.

Another relevant and interesting finding was the relationship between breakfast consumption and active commuting to school. Although there is little and inconsistent scientific evidence available(Reference Jago, Ness and Emmett21), it might be assumed that healthy behaviours lead to other healthy behaviours(Reference Driskell, Dyment and Mauriello22). For example, a healthy behaviour such as adequate sleep duration was positively associated with active commuting to school in the present study. In contrast, a well-known healthy behaviour such as eating breakfast has been inversely associated with active commuting to school. A possible explanation is that adolescents prefer to spend their time eating breakfast rather than actively commuting to school or that those adolescents who have to use inactive modes of commuting to school have more time to eat breakfast. Irrespective of the reason, skipping breakfast cannot be a recommended strategy to increase active commuting to school among adolescents(Reference González-Gross, Gómez-Lorente and Valtueña13); therefore public health strategies should promote both eating breakfast and active commuting to school as healthy habits in adolescence. Since our findings were independent of several socio-economic and demographic characteristics, other key factors that might mediate the associations between eating breakfast and commuting to school must be examined in future research.

We also found that other healthy behaviours were not associated with active commuting to school in Spanish adolescents; for example, adolescents with high levels of overall and extracurricular physical activity did not have a higher prevalence of active commuting to school. Some studies have demonstrated that adolescents who commute actively to school tend to be more physically active than passive commuters, although this evidence is less clear in adolescents than in children(Reference Troiano, Berrigan and Dodd3). For example, Santos et al.(Reference Santos, Oliveira and Ribeiro23) showed that organized and non-organized physical activity after school was not predictive of active commuting to school in Portuguese adolescents. Hohepa et al.(Reference Hohepa, Scragg and Schofield24) found that Australian adolescents who actively commute to school were not active during other periods such as morning recess, lunch breaks and after-school activities during school days. Conversely, two studies in German and American adolescents showed that active commuters reported higher levels of physical activity(Reference Landsberg, Plachta-Danielzik and Much25, Reference Robertson-Wilson, Leatherdale and Wong26). The difference between studies may be partially explained by how physical activity was measured. The aforementioned studies and our study used self-report measures; however, several studies in adolescents have shown that objectively measured physical activity (i.e. accelerometry) is positively associated with active commuting to school in Northern European countries(Reference van Sluijs, Fearne and Mattocks27, Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz28).

Patterns of sedentary behaviour such as television viewing and reading as a hobby were not significantly associated with active commuting in the present study. Likewise, Mota et al.(Reference Mota, Gomes and Almeida29) showed that neither television viewing nor computer usage was a predictor of active commuting to school in a sample of Portuguese adolescents. Robertson-Wilson et al.(Reference Robertson-Wilson, Leatherdale and Wong26) also found that the amount of sedentary time was not a consistent predictor of adolescents’ active commuting to school. In contrast, Landsberg et al.(Reference Landsberg, Plachta-Danielzik and Much25) showed that television viewing was lower in actively commuting adolescents, although these observations were not adjusted for socio-economic or demographic variables since this was not the principal aim of their study. It should be noted that the above studies used average variables of sedentary behaviour in a habitual week, whereas we tested these associations using data for school days.

Irrespective of breakfast consumption, we included fruit intake as another indicator of healthy diet and found no significant association with active commuting to school. Landsberg et al.(Reference Landsberg, Plachta-Danielzik and Much25) also found that dietary patterns were not associated with active commuting to school in 14-year-old adolescents. Finally, we also investigated whether habitual smoking or alcohol intake was associated with active commuting to school. Previous studies suggested that alcohol intake is not a predictor of active commuting to school(Reference Robertson-Wilson, Leatherdale and Wong26), whereas adolescents who are habitual smokers tended to commute to school using inactive modes(Reference Landsberg, Plachta-Danielzik and Much25, Reference Robertson-Wilson, Leatherdale and Wong26). Our findings support these results with regard to alcohol intake but not with respect to smoking patterns.

The adolescent sample studied herein showed a similar prevalence of active commuting to school as European(Reference Landsberg, Plachta-Danielzik and Much25, Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz28–Reference Andersen, Lawlor and Cooper30) and Asian(Reference Tudor-Locke, Ainsworth and Adair31) adolescents and slightly higher than American(Reference Robertson-Wilson, Leatherdale and Wong26) and Australian adolescents(Reference Hume, Timperio and Salmon32). Nevertheless, the prevalence found was slightly lower (−10 %) than in a previous study of Spanish adolescents(Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz8). The AVENA (Alimentación y Valoración del Estado Nutricional en Adolescentes; Food and Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Adolescents) study showed that up to 65 % of Spanish adolescents reported active commuting to school and 83 % of them spent less than 15 min travelling to school(Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz8). Significant differences between the present study and the AVENA study make correct comparisons difficult, although the prevalence of active commuting to school found in both these studies suggests that Spanish adolescents meet the public health recommendations of 50 % walking to school but do not meet the recommendation of 5 % cycling to school promoted by the US Department of Health and Human Services (www.healthypeople.gov). This fact has public health implications since several studies have shown that cycling to school may have greater benefits on health (e.g. physical fitness) than walking to school(Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz28, Reference Andersen, Lawlor and Cooper30). These findings therefore highlight the need for strategies to encourage adolescents to cycle to school, particularly the provision of adequate facilities and safe routes to school in metropolitan areas(Reference Davison, Werder and Lawson6).

Several specific limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish causality. Thus our findings might be subject to reverse causality (e.g. skipping breakfast could be a cause of active commuting to school or active commuting to school could be a cause of skipping breakfast) and prospective studies may prove valuable in examining this issue. Second, behavioural correlates were self-reported and these results must be interpreted with caution. Self-report measurements are subjective and rely on memory. Furthermore, the sporadic nature of adolescents’ behaviour makes some activities (e.g. physical activity) difficult to recall and quantify(Reference Sirard and Pate33). Third, relevant measures of deprivation such as income, education or occupation were not available in the AFINOS study. This fact warrants further studies investigating the role of socio-economic inequalities on the associations between lifestyle factors and active commuting to school. This future research direction is important since a previous study in Spanish adolescents showed that several deprivation measures seem to be inversely related to active commuting to school(Reference Chillón, Ortega and Ruiz8). Consequently, the associations of sleep duration and breakfast consumption with active commuting to school found in our study might be mediated by a deprivation status. We performed post hoc analyses controlling for the number of computers at home since this indicator is used in the Family Affluence Scale (FAS)(Reference Currie, Molcho and Boyce34). The FAS is based on the concept of material conditions in the family as a measure of deprivation(Reference Currie, Molcho and Boyce34). In these analyses the main results did not change but we found an inverse association between the number of computers at home and active commuting to school. Finally, we cannot know whether the associations between breakfast consumption and commuting to school differ by the place where the adolescent usually eats breakfast (i.e. at home or during the trip to school).

In summary, adequate sleep duration is positively associated with active commuting to school in adolescents, whereas adolescents who eat breakfast are less likely to commute actively to school. The links between these lifestyle factors and active commuting to school need to be investigated in greater depth in order to tailor public health strategies in adolescence.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (DEP2006-56184-C03-02/PREV) and EU funding (FEDER). D.M.-G. received a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (AP2006-02464). None of the authors had any conflicts of interest. Authors’ responsibilities: D.M.-G. conducted the statistical analysis; D.M.-G. drafted the manuscript; A.M., O.L.V., M.E.C. and S.G.-M. obtained funding and contributed to the overall concept and design; D.M.-G., A.M., O.L.V., M.E.C., S.G.-M. and B.Z. contributed to the interpretation and acquisition of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank all the adolescents and their families for their participation.

Appendix

AFINOS Study Group

Study coordinator: A. Marcos.

Sub-study coordinators: M.E. Calle, A. Villagra and A. Marcos.

Sub-study 1: M.E. Calle, E. Regidor, D. Martínez-Hernández and L. Esteban-Gonzalo (Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain).

Sub-study 2: A. Villagra, O.L. Veiga, J. del-Campo, J.M. Moya, D. Martínez-Gómez and B. Zapatera (Department of Physical Education, Sport and Human Movement, Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain).

Sub-study 3: A. Marcos, S. Gómez-Martínez, E. Nova, J. Wärnberg, J. Romeo, L.E. Diaz, T. Pozo, M.A. Puertollano, D. Martínez-Gómez, B. Zapatera and A. Veses (Immunonutrition Research Group, Department of Metabolism and Nutrition, Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition (ICTAN), Instituto del Frio, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, Spain).