Observers within and outside of the international relations (IR) subfield of political science bemoan a growing gap between theory and practice. In a 2009 op-ed, Joseph S. Nye, Jr., a Harvard-based political scientist who served as Assistant Secretary of Defense and chair of the National Intelligence Council, criticized IR scholars for staying “on the sidelines” and ignoring their “obligation to help improve on policy ideas when they can” (Nye Reference Nye2009). Robert Gallucci (Reference Gallucci2012)—an academic, dean, and MacArthur Foundation president, who previously served as US ambassador to a United Nations Special Commission—similarly wrote, “The worlds of policy making and academic research should be in constant, productive conversation, and scholars and researchers should be an invaluable resource for policy makers, but they are not.” New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof (Reference Kristof2014) shared Nye’s and Gallucci’s grievance when he complained, “My onetime love, political science...seems to be trying, in terms of practical impact, to commit suicide.”

Many of these critiques of academic IR—and political science more generally—blame an academic incentive structure that privileges quantitative over qualitative work (Avey and Desch Reference Avey and Desch2014) and abstract theoretical over applied research (Gallucci Reference Gallucci2012). These critics condemn a scholarly culture that professionally rewards those who write primarily for one another rather than practitioners (Nye Reference Nye2009). Academic norms and practices discourage scholars from undertaking work that might inform practitioners (Walt Reference Walt2005), producing what Van Evera (Reference Van Evera2010) termed a “cult of the irrelevant.” Campbell and Desch (Reference Campbell and Desch2013) exhorted political scientists to define academic excellence broadly enough to include contributions to policy debates. Van Evera (Reference Van Evera2015) concluded that we must dramatically “reorganize the social sciences to create multidisciplinary academic departments that are focused on problems” if we want to create a more innovative and relevant academic culture.

This article takes a step toward determining whether the incentive structure within the IR discipline inhibits policy-relevant work by exploring IR scholars’ perceptions of the role of such research in the discipline.

This article takes a step toward determining whether the incentive structure within the IR discipline inhibits policy-relevant work by exploring IR scholars’ perceptions of the role of such research in the discipline. We found that these scholars believe that more policy-relevant publications are undervalued in academic tenure decisions. Our findings were similar even when accounting for a number of potential explanatory factors. However, scholars who consult outside of academia, are untenured, conduct applied research, teach at colleges rather than research universities, or teach in Association of Professional Schools of International Affairs (APSIA) schools rather than political science departments are likely to believe that policy-relevant research is currently valued more highly than their colleagues estimate and, on the normative question, that it should be valued more highly still.

ARGUMENT

For critics of current professional incentives, the challenge is to coordinate large-scale change in the evaluation of policy-oriented work. To encourage policy work, or prevent the systematic purging of scholars who do this type of work, reformers must change what they suggest is the current consensus, which undervalues policy-relevant publications. Such a shift is predicated on changing second-order beliefs. It is not enough to convince scholars of the benefits of policy-relevant work; any sustainable strategy requires that scholars also believe that other scholars—who will write tenure letters and vote on tenure decisions—hold similar views.

It may be that the status quo is acceptable to most IR scholars and that critics like those discussed previously are exceptions. It also is possible, however, that we live in an observationally equivalent world to the one lamented by the critics, one in which most scholars agree that policy work is undervalued but remain unaware that they are part of a silent majority. To better understand views on policy-oriented research, we attempted to answer the following four questions:

1. What are the second-order beliefs of IR scholars about how they think their colleagues value various research products?

2. Do scholars believe that the value of various research products should be what it currently is?

3. Do scholars vary systematically in their second-order beliefs about the value of different research outputs?

4. Do scholars vary systematically in how they believe different research products ought to be valued?

To address these questions, we analyzed data from the 2014 US TRIP Faculty Survey of IR scholars. TRIP adopts an expansive definition of “IR scholar” as anyone affiliated with a university, college, or professional school who teaches or publishes research on political issues that cross international borders. The majority of respondents work in departments of political science, politics, government, social science, and IR or in professional schools of international affairs. We omitted scholars who study or teach international economic, legal, or social—but not political—issues. We identified a total of 4,123 individuals in the United States who met our criteria for inclusion. Of these individuals, 1,620 answered the survey, for a response rate of 39.29%.Footnote 1

We drew on the results of the following two questions:

1. “At your current institution, how are the following kinds of publications valued relative to an article in a top peer-reviewed journal at the time of the tenure decision (or its equivalent)?”

2. “How should the discipline value the following kinds of publications relative to an article in a top peer-reviewed journal at the time of the tenure decision (or its equivalent)?”

Respondents rated outputs numerically and in relation to the baseline category—fixed at 100—of an article published in a top peer-reviewed journal. Thus, if respondents wanted to state that some output is worth half an article, they assigned that output a value of 50.Footnote 2

Response categories included seven types of publications. We considered blog posts in leading IR or political science blogs; op-eds or articles in national newspapers and magazines; policy reports for government agencies, international organizations, and private foundations; and articles in top policy journals to reflect more policy-relevant research than book chapters in edited volumes, books at top commercial presses, and books at top university presses. This assumption was based on the time to publication, nature of the audience targeted, and presence of explicit policy prescriptions. Blog posts, op-eds, policy reports, and policy articles have a significantly shorter publication process; are more likely to directly engage a policy audience or public debate; and are more likely to offer explicit policy recommendations. Practitioners often lack time to read academic journals and books, and they want information in real time (Bennett and Ikenberry Reference Bennett and Ikenberry2006; Desch Reference Desch2009). It makes sense that practitioners also will be more influenced by works that provide explicit policy guidance. Such advice may flow from basic research also embedded in books and articles, but those works take far longer to get to print and contain fewer policy prescriptions. Fewer than 9% of the 7,792 peer-reviewed articles in the TRIP Journal Article Dataset and only 17.30% of the 1,004 books in a TRIP pilot study contained explicit prescriptions, compared to 41.37% of articles in the 1,477 articles included in our study of the two policy journals, Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy.Footnote 3

We also understand that many readers may question respondents’ claims that a blog post in a top blog should count as 26% of a top article.

We recognize that our publication categories are not exhaustive. We also understand that many readers may question respondents’ claims that a blog post in a top blog should count as 26% of a top article. This does not mean that most scholars would vote to tenure a candidate with four more top blog posts compared to a candidate with one more top peer-reviewed article. Instead, we believe that the comparisons between the is and the ought—especially across different types of respondents—suggest where there is interest in rewarding policy-relevant work within the academy.

RESULTS

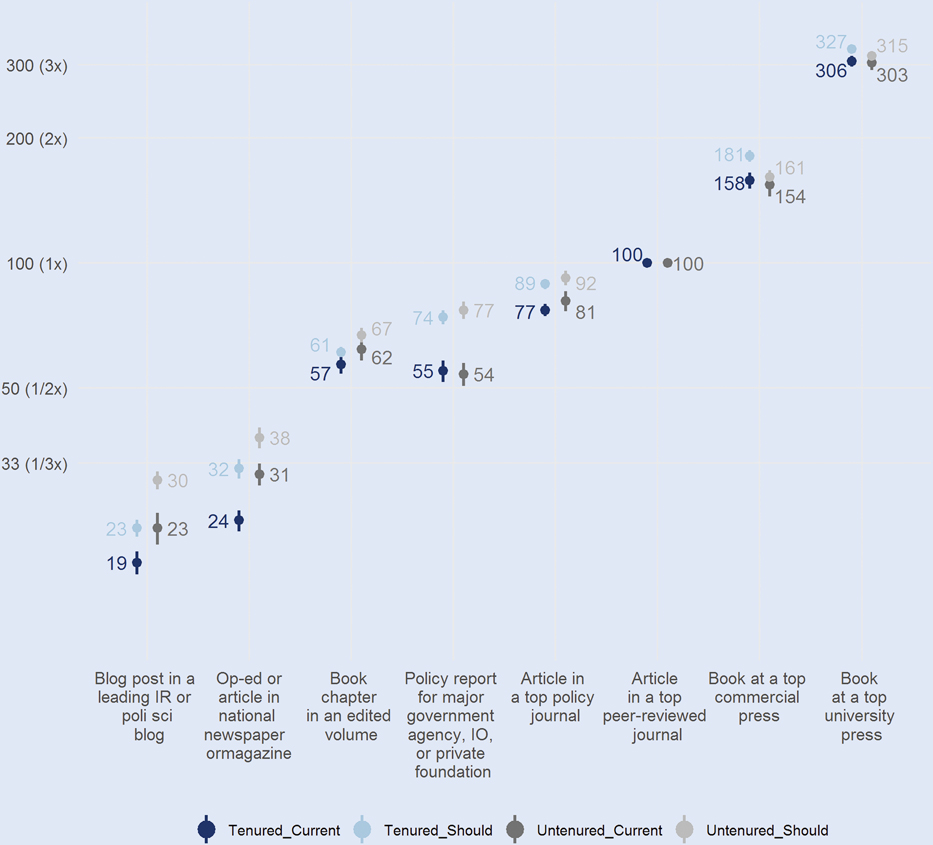

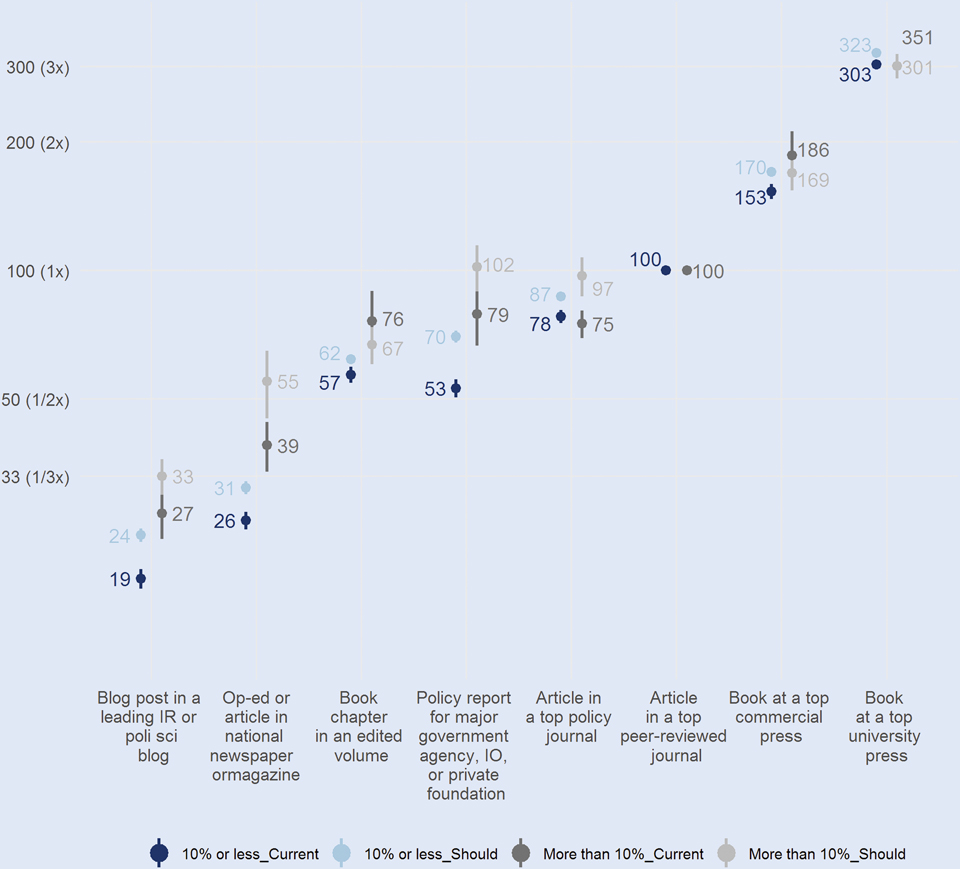

IR scholars generally believe that much of their work (and/or that of their colleagues) is undervalued at tenure time relative to an academic article in a top peer-reviewed journal. Figure 1 compares data for all respondents on beliefs about both current standards at their academic institution and what they think those standards should be. Directly addressing question 1, there is a clear and largely unsurprising ranking in respondents’ second-order beliefs on the seven types of publications. Regarding question 2, however, respondents believe that all publication types are valued less by their current institution than they should be by the IR discipline.

Figure 1 Value of Publications in Tenure Decisions

Nevertheless, there are important differences across publication types. Gaps between respondents’ second-order beliefs about and the value of policy-relevant publications—blog posts, op-eds and newspaper articles, and policy reports—are larger than for more traditional, scholarly research products such as books and book chapters. Reports, for example, are generally perceived to be worth slightly more than half of a top peer-reviewed article, whereas respondents believe these reports should be worth about 75% of an academic article. An op-ed or newspaper/magazine article is worth slightly more than 25% of a peer-reviewed article, but it should be worth more than 33%, according to respondents.

We turn now to questions 3 and 4 and consider whether and how much factors—including respondents’ tenure status, engagement in policy activities and policy-relevant research, and type of educational institution at which they teach—influence their second-order beliefs about the value of policy-relevant research. It is possible, for example, that untenured faculty have different perceptions of the relative value of various types of publications than their senior colleagues. If tenured scholars set tenure standards, then differences in beliefs about the content and utility of current standards are important. Similarly, tenured scholars’ normative preferences are important for informing any effort to change such standards. Figure 2 distinguishes tenured from untenured scholars based on rank by grouping together associate and full professors; we assume that assistant professors and instructors or lecturers do not have tenure.Footnote 4

Figure 2 Value of Publications in Tenure Decisions—The Effect of Having Tenure

We found similar response patterns across tenured and untenured scholars, although we also identified important differences between the two groups.Footnote 5 Both groups believe that all forms of publications (except books) are undervalued. Both tenured and untenured faculty agree that blog posts, op-eds, book chapters, policy reports, and policy articles should carry more weight in the tenure process. Moreover, untenured IR scholars believe that policy-relevant publications are valued more highly and that they should be valued even more highly than their tenured colleagues believe. Finally, IR scholars tend to agree about how policy reports are currently valued and that these reports should be counted about half again as much as they are.

Although tenure status and age are likely to be highly correlated, we separately analyzed the results by age because these evaluations might reflect different prevailing disciplinary norms during the socialization of tenured and untenured scholars or different career incentives by age.Footnote 6 In general, there is no clear difference in the evaluations by age. Most of our observations occurred in the “under 45” and “45–65” age groups, and these results were consistent with the untenured-versus-tenured results. We have limited observations in the “over 65” group and therefore wide error bars; however, older faculty appear to believe that blog posts and op-eds should be more highly valued than their younger colleagues believe, and the gap between is and ought is greatest for those faculty over age 65.

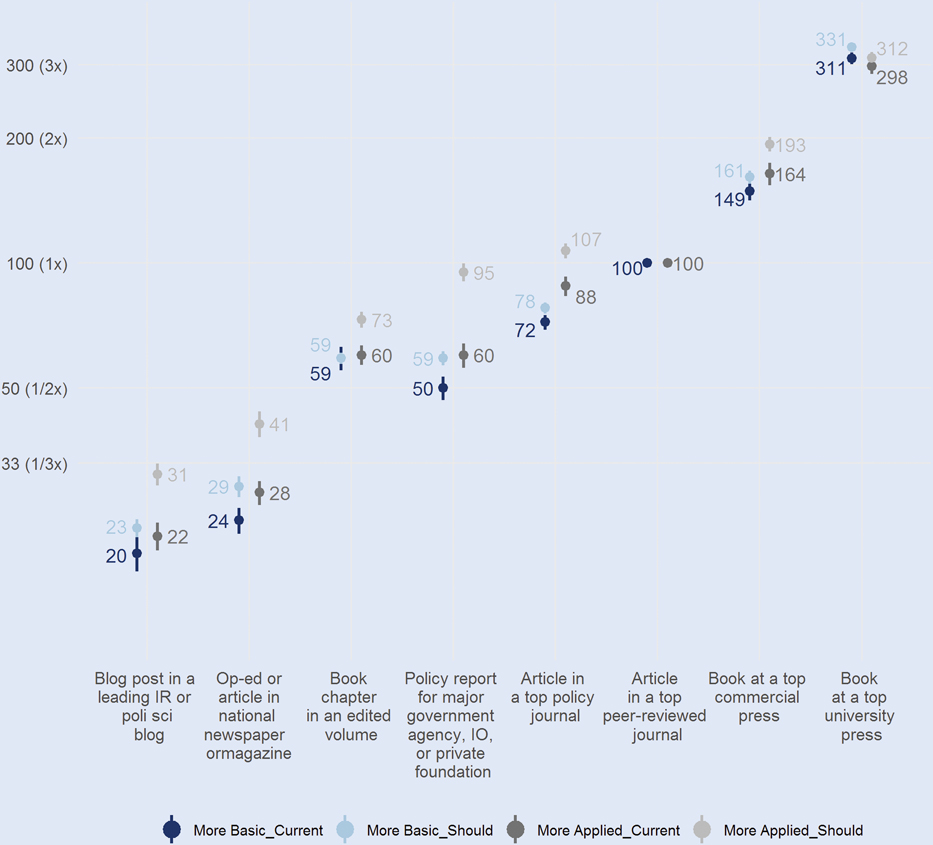

Like tenure status, scholars’ engagement in policy-relevant work may bias their views on the importance of research output in tenure decisions. Consistent with the “bridge-builders’” laments cited previously, perhaps scholars who do applied work believe it is undervalued within the academy. Alternatively, because people want to believe that the work they do is valuable (and valued by their institution), they may believe policy-relevant work is (and should be) valued in tenure decisions (Bastardi, Uhlmann, and Ross Reference Bastardi, Uhlmann and Ross2011). We found that respondents who described their work as more applied consistently stated that blogs, op-eds, policy reports, and policy articles should count more heavily in the tenure decision than those whose research is less applied.

Figure 3 compares IR scholars who stated that their research is more applied with those who described their work as more basic. This evidence comes from the TRIP survey question, “Does your research tend to be basic or applied? By basic research, we mean research for the sake of knowledge, without any specific policy application in mind. Conversely, applied research is done with specific policy applications in mind.”Footnote 7 Figure 3 illustrates consistency among IR scholars—regardless of the policy relevance of their own research—in their assessment of the current value of different types of research in tenure decisions. Gaps open on the normative side, however. Respondents who described their work as more applied stated that blogs, op-eds, policy reports, and policy articles should count more in tenure decisions than their colleagues whose research is more basic. By a narrower margin, they also believe that book chapters and commercial books should have greater value.Footnote 8

We found that respondents who described their work as more applied consistently stated that blogs, op-eds, policy reports, and policy articles should count more heavily in the tenure decision than those whose research is less applied.

Figure 3 Value of Publications in Tenure Decisions—Basic or Applied Research

Perhaps a better measure of scholars’ engagement with the policy world is behavioral: whether they work as consultants for governmental or non-governmental organizations. As shown in figure 4, IR scholars who regularly consult believe that policy-relevant research is more valued and should be valued even more highly than it is in tenure decisions, relative to their colleagues who spend little or no time consulting. The results from the normative question were unsurprising because scholars who consult more have an interest in rewarding publications that emerge from such arrangements. The finding on how policy publications are currently rewarded may or may not be surprising, depending on one’s prior beliefs about whether faculty members seek excuses for negative tenure decisions or are motivated to misperceive the preferences and behaviors of their colleagues.

Figure 4 Value of Publications in Tenure Decisions—Consulting

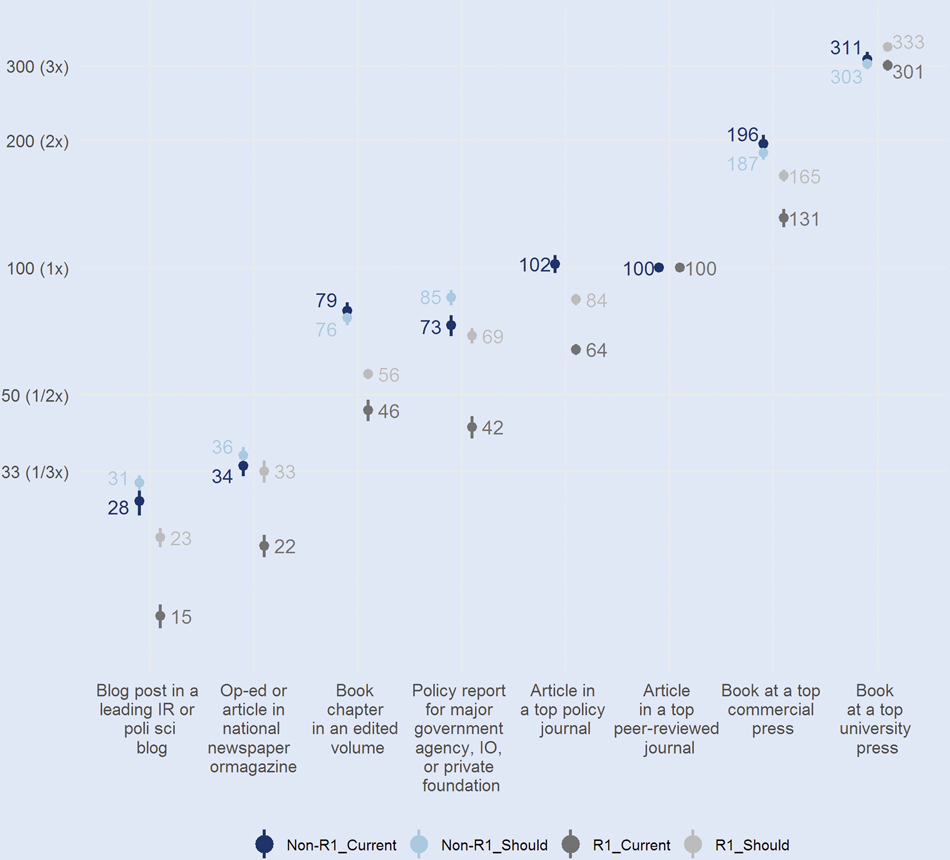

If academic norms actively discourage policy-relevant work, then where one teaches should affect one’s estimate of the value of publication types in the tenure process. IR scholars at major research (R1) universities generally teach less and engage in more academic research than their counterparts at liberal arts colleges. In short, R1 scholars embody the culture that Nye (Reference Nye2009), Walt (Reference Walt2005), and others railed against. We therefore expected that faculty at R1s would report that their institutions value policy work less highly in tenure deliberations than faculty at non-R1 institutions. We also expected R1 faculty to state that the discipline should assess these research products less highly than their non-R1 counterparts.

The results in figure 5, which uses US News and World Report education rankings to categorize institution type, confirmed our expectations. First, faculty at non-R1s value all forms of research more highly than faculty at research universities. Second, the gaps between is and ought are small or non-existent at non-R1 institutions; that is, faculty at these schools generally believe that their institutions weight research output the way the discipline should. At R1s, however, respondents generally believe that every type of research output should be more highly prized than it is. For this reason—and contrary to conventional wisdom—research universities may be the most receptive to change (at least at the faculty level) and the creation of a culture that further incentivizes policy work.

Figure 5 Value of Publications in Tenure Decisions—R1 Versus Non-R1

Within the R1 subsample, we compared IR scholars at policy schools to those in traditional political science departments. On the normative question, we expected that faculty at policy schools believe that the discipline should give more weight to policy-focused output than scholars who work in traditional departments. The data confirmed our expectations: compared to non-APSIA faculty, APSIA faculty reported that their institutions give greater weight to nearly all types of publications—but especially policy-relevant work.Footnote 9

We expected that APSIA deans and political science department chairs, whose preferences are shaped by the goals of their different units within the university, also hold different beliefs about the current and preferred value of policy publications. We compared the responses of the deans of APSIA schools located in the United States with the chairs of the top 50 political science departments in the country. We found that APSIA deans, like their faculty, believe that policy publications—blog posts, op-eds, policy reports, and policy articles—count more in the tenure process than political science department chairs believe.Footnote 10 Similarly, they think that these research products should count more than their counterparts who serve as department chairs. Deans of interdisciplinary policy schools do not feel the same way about more academic publications such as books, however. The gap between deans and chairs, predictably, was not as wide as that between APSIA faculty and all other faculty.Footnote 11

CONCLUSION

The data suggest that those who are concerned that academic incentives, particularly tenure standards, discourage policy-relevant work may be right: at least, IR scholars believe that policy publications are undervalued in tenure decisions. Regardless of whether respondents to the TRIP survey have tenure or consider their own research to be policy relevant, they believe that policy-relevant publications should carry greater weight at tenure time than they do. However, IR scholars’ perceptions of the current worth of policy publications, as well as their beliefs about how these research products should be valued, vary depending on their involvement in the policy process and the type of school where they teach. Faculty who consult for governmental or non-governmental agencies, teach at colleges rather than research universities, and teach in APSIA schools rather than political science departments believe that policy-relevant work is currently worth more at tenure time than their colleagues estimate. On the normative question, these scholars believe that policy publications should be valued more highly still.

At first glance, this might suggest that scholarly culture is unlikely to change because faculty at major research universities believe that policy publications should be prized less highly than non-R1 faculty believe. Nevertheless, the gap at R1s between how faculty think policy publications are valued and how they think those works should be valued is considerably larger than at non-research institutions. This suggests room for change. In short, IR scholars’ current perception of constraints on policy-relevant work at leading universities may be better described as a shared misperception. Faculty generally believe that policy research should be valued more highly by the discipline but, paradoxically, they also believe that the profession does not value it highly enough. Additionally, the tendency of APSIA faculty—who in most cases teach at the same universities as colleagues in the top 50 political science departments and who may even hold joint appointments in those disciplinary departments—to believe that policy-relevant work is and should be valued more highly than their political science colleagues further suggests that change is possible. After all, decisions about tenure and promotion are made at department and university levels.

Regardless, the gaps we found between faculty beliefs about the current value of policy work and their normative beliefs about how such work should be valued are statistically significant and substantively large. This suggests that there is interest in reform among faculty members who play a major role in setting tenure standards and making tenure decisions.

Of course, we recognize that institutions change slowly. The normative beliefs of the IR scholars that we surveyed demonstrate preferences for changes to tenure standards, even at R1 universities. Those preferences are not universally held, however. Some scholars may believe that such work should not be highly valued. Others may think that policy research already is highly valued. They may believe that their institutions value such work or that basic research ultimately produces policy prescriptions and therefore is itself policy relevant. Even if preferences for change were universally shared, current standards that undervalue policy publications are built into departmental, tenure-committee, and university policies that privilege scholarly publications. These institutions are likely to be resistant to change, even when many IR scholars welcome it.

Moreover, the data presented here are self-reported attitudes, with the usual caveat about the ability of respondents to accurately assess the field as well as the warning that beliefs may not match tenured professors’ behavior in real tenure cases. Tightly designed experiments would correct for this problem and offer important insights, but the way that faculty claim to see their field is likely the measure that best matches the stories that senior faculty tell their junior colleagues and graduate students about how to climb the academic career ladder. These narratives probably also best represent frustrations that scholars have with what they see as the field’s current undervaluation of policy-relevant publications relative to traditional academic outputs. They also may be part of the story that those who fail or succeed at tenure tell themselves and others. Insofar as this is true, we think that the results reported in this article can inform conversations within universities and departments as well as guide the reform proposals of those advocates who seek to bridge the gap between the academic and policy communities within IR.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518001804