Young, adult, and elderly [Mayan] women in Guatemala are making changes in their lives, to generate wellbeing and good living for themselves, other women, and their communities. Despite all the inequities, oppressions, violences of a system that prioritizes injustice and death, there is enough joy, creativity, desire for life, for being and becoming, and as such, women are defending life, territory and body.

Introduction

Guatemala’s post-genocide landscape has been marked by an increasing turn to transitional justice and its four pillars of truth, justice, reparations and guarantees of non-repetition (Reference TeitelTeitel, 2000) as a means to redress the ongoing effects of thirty-six years of devastating armed conflict (1960–1996). Truth-telling reports traced the roots of the conflict to the extremely skewed inequities of economic and political power resulting from a history of colonial dispossession of Indigenous lands and livelihoods (CEH, 1999; ODHAG, 1998). The United Nations (UN)-sponsored Historical Clarification Commission (CEH) documented overwhelming numbers of killings, disappearances, massacres and forced displacement, found that acts of genocide were committed against specific Mayan communities at the height of the state’s scorched earth policies in the early 1980s (CEH, 1999, vol. 3: 358) and highlighted the perpetration of sexual violence, predominantly against Mayan women (CEH 1999, vol. 3: 23). Beginning in 2003, a controversial and highly contested National Reparations Programme (PNR) was implemented by the Guatemalan state to provide mostly monetary compensation to some victims of the war (Reference Crosby and LykesCrosby and Lykes, 2019: 135–139). Additionally, a ‘judicial spring’ has seen a number of high-level prosecutions, including the 2013 genocide trial of former de facto head of state General Efraín Ríos Montt (Reference Oglesby and NelsonOglesby and Nelson, 2016) and the 2016 Sepur Zarco trial of two former members of the Guatemalan military for sexual violence as a crime against humanity (Impunity Watch and the Alliance, 2017).

The turn to transitional justice as a means for redress has required victims, mostly Mayan, to recount their experiences of devastating violence over many years to a multiplicity of interlocutors or intermediaries (Reference MerryMerry, 2006), including state officials, lawyers, judges, psychologists, activists and researchers, ourselves included. Survivors of sexual violence have risked identification as ‘the raped woman’ as they are called upon to detail this specific harm. Like many Western rights regimes, transitional justice mechanisms are damage-centred (Reference TuckTuck, 2009) and rely upon survivors’ narratives of individuated events of pain and loss, supported and validated by expert witnesses, to prove harm suffered. Indigenous scholar Eve Reference TuckTuck (2009: 416) has warned of the dangers for Indigenous communities of such (externally imposed) ‘damage narratives’ which pathologise them as essentially broken. As such, these narratives are themselves acts of epistemic violence that can undermine and occlude Indigenous resilience. Reference TuckTuck (2009: 416) instead argues for ‘desire-based frameworks’, which entail ‘understanding complexity, contradiction, and the self-determination of lived lives’.

In this chapter, we take up Tuck’s challenge of a desire-based framework in seeking to understand Mayan women’s resilience, here defined by them as ‘resistance, persistence, permanence, strength and determination’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 57), in relation to their engagement with transitional justice processes in post-genocide Guatemala. We document how diverse groups of Mayan women who have participated in trials, testified in truth-telling processes and organised in defence of their individual and collective rights have reframed these experiences of resistance and resilience to centre their ‘lives, cosmovision and knowledge of a collectivity’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 57; see also Reference Crosby and LykesCrosby and Lykes, 2019). We draw on our respective participation in separate processes of accompaniment of these Mayan women protagonists and our current reflexive engagement with what we have learned from these processes and through ongoing conversations among ourselves as co-authors.

Reference TuckTuck’s (2009) critique of damage narratives is centred on research with Indigenous communities – conducted by often well-meaning external researchers – that seeks to document pain and loss as a means to effect change and achieve reparation. We have accompanied Mayan women as intermediaries through diverse transitional justice processes, and, as such, our work has been at the interstices of Mayan and Western onto-epistemologies. Mindful of the need to be ‘held accountable for the frameworks and attitudes [we] employ’ (Reference TuckTuck, 2009: 412), in this chapter we draw on feminist physicist Karen Reference BaradBarad’s (2007: 185) theorisation of agential realism and her call for an ‘ethico-onto-epistem-ology’ that strives for ‘the intertwining of ethics, knowing and being’.

As North American researchers who have worked in Guatemala for many years, Lykes and Crosby are mindful of their own location within the colonial relations of power that Reference TuckTuck (2009) critiques and ‘the arrogance and absence of reflexivity afforded by white supremacy’ (Reference TuckTuck, 2009: 412). They have sought to be critically reflexive of their role in reinforcing Western onto-epistemological assumptions that underpin both transitional justice and social science research by those from the global North. In this collaboratively written chapter, they re-examine their previous work, which entails an unpacking of and turning away from the Western dualisms that have informed their thinking and being (as well as that of the transitional justice paradigm itself), to more self-consciously deepen their engagement with Mayan onto-epistemologies that reflect a more integrated relationship between the human and non-human, between land, body and territory (Reference Chirix García, Leyva Solano and IcazaChirix García, 2019). For Alvarez, a focus on the Mayan cosmovision or worldview as onto-epistemology reflects her positionality as a K’iche’ woman whose urban location and multiple experiences as an intermediary have challenged her to ‘look both ways’ in transitional justice work for a (predominantly ladinx,Footnote 1 Western-oriented) human rights organisation in Guatemala that accompanies Mayan communities, among others. As such, she is mindful of the colonial dynamics at play within the transitional justice realm within which she engages and the challenges this presents for her decolonial praxis and her accountability towards her Indigenous collectivity.

For all three of us, our differing and differentiated positionings as intermediaries accompanying Mayan women protagonists in their struggles for redress affect what we can and cannot see or hear in relation to their expressions of resilience rooted in Mayan onto-epistemology. The latter is emergent from and circulates through individuals, families, communities, the wider society and all living beings as interdependent systems (Ungar, Chapter 1) that are constrained by and resist ongoing colonial relations of power in which we ourselves are deeply implicated. As such, we strive to facilitate processes of relationality and dialogic engagement in accompanying these Mayan protagonists’ persistence. This positioning and these experiences of accompaniment have contributed to the argument presented herein; that is, that the temporally limited, linear transitional justice paradigm resists redress of the ongoing harms of structural colonial violence. This chapter acknowledges and affirms the persistence and protagonism of Mayan women in communities that have endured and indeed continue to thrive as they, women-in-community, transform in their defence of the integrality of land-body-territory. In addressing the systemic factors that can support Indigenous communities in redressing colonial violence, we thus argue for a conception of historical justice that supports Indigenous people’s self-determination on their lands and through their livelihoods grounded in their own cosmovision. As Reference Tuck and YangTuck and Yang (2012: 10) have stated, ‘decolonization is not a metaphor’ and instead requires ‘the relinquishment of land, power and privilege’ by the colonisers.

Onto-Epistemology: Land-Body-Territory

Practices of knowing and being are not isolable; they are mutually implicated. We don’t obtain knowledge by standing outside the world; we know because we are part of the world. We are part of the world in its differential becoming. The separation of epistemology from ontology is a reverberation of a metaphysics that assumes an inherent difference between human and nonhuman, subject and object, mind and body, matter and discourse.

Recent scholarship on resilience and adaptive peacebuilding has critiqued an over-emphasis on individual resilience, insisting instead on sustainable processes that foster ‘interactions between individuals and their environments’ (Ungar, Chapter 1) and accentuate ‘complexity’ and ‘local ownership’ as well as resilience (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 305). It is therefore necessary to address ‘the systemic dimensions of war crimes and human rights abuses’, as well as to ‘engage with different systems that give people access to new resources’ (Ungar, Chapter 1). In this section, we extend this complexity, drawing on Mayan scholars and activists who press for a recognition of multiple onto-epistemologies within a pluriverse (Reference Esteva and PrakashEsteva and Prakash, 2014). We analyse how multi-systems and relational approaches to resilience work to disrupt Western dualisms of nature and culture, of human and nonhuman, of knowing and being, that themselves are the result of colonial violence and dispossession. Indigenous resilience is rooted in an integral, collective relationship of land-body-territory.

In post-genocide Guatemala, questions of land and territory haunt transitional justice processes focused on redress for bodily harm, including rape, torture, forced disappearances and massacres. The colonial dispossession of Indigenous lands remains the primary, foundational and ongoing injustice, and Indigenous communities throughout the country are mobilised today around defensa del territorio (territorial defence) in the face of the rampant, violent extractivism of transnational corporations that is enthusiastically supported by the Guatemalan state (Reference Macleod and SiederMacleod, 2017; Reference Solano, McAllister and NelsonSolano, 2013). In the Sepur Zarco case of sexual violence as a crime against humanity, the Q’eqchi’ women plaintiffs’ husbands were disappeared because they were organising to legalise their titles to their lands, and as a consequence the women endured forced labour and sexual violence at the Sepur Zarco military outpost. Despite participating in a trial focused on redress for sexual violence, the plaintiffs contested the construction of their experiences of rape as isolated, individuated events; instead, they sutured their bodies to the land and to the Q’eqchi’ collectivity of which they are part. As such, their resilience is rooted in their (re)connection to their Mayan community and land and to the demand for the land’s return, rather than in the identity as a ‘raped woman’ that emerged through the trial. The trial’s still unfulfilled reparations ruling of land legalisation remains a gaping, egregious wound. Today, Sepur Zarco continues to be a private estate, surrounded by African palm plantations. The colonial violence lives on, as does Indigenous resistance to it (Reference Crosby and LykesCrosby and Lykes, 2019; Reference Méndez and CarreraMéndez and Carrera, 2014).

The Sepur Zarco trial did deliver a guilty verdict. It was the first time that these crimes had been prosecuted in-country, and the verdict was celebrated transnationally as a victory for gender justice. What was striking was the absence of any recognition of indigeneity in the way in which the trial was received and analysed by many who attended and in national and international media; the exclusive focus on gendered sexual violence reflected what appeared to be an inability to see or hear the intersectional violations experienced and the call for historical justice. This absence permeated the transitional justice processes themselves, where there was a seeming refusal to turn towards the Mayan cosmovision, despite the fact that the majority of those seeking redress were themselves Mayan – and both they and expert witnesses at the trial had testified to those realities (Reference Velásquez Nimatuj, Mendia Azkue and Guzmán OrellanaVelásquez, 2012). Structural, institutionalised racism remains an entrenched, systemic barrier to historical justice for Mayan peoples. As the Kaqchikel scholar Emma Reference Chirix García, Leyva Solano and IcazaChirix García (2019: 147) argues, ‘it is not possible to understand the Mayan conception of the world from the Western vision, because Eurocentric and ethnocentric knowledge distorts, rationalises, racialises, subordinates and violates indigenous knowledges’.

The Mayan cosmovision is heterogeneous, reiterated in different forms by the twenty-two Mayan peoples in Guatemala, and fragmented, dissipated and transformed across centuries of colonisation. However, the cosmovision has enduringly held to a core onto-epistemology of complementarity and equilibrium, whereby knowing and being are inextricably intertwined, and the relationship between human beings and Mother Earth is mutually constituting and interdependent. As Reference Chirix GarcíaChirix García (2003: 23) elaborates, echoing the multi-systemic approach to resilience and adaptive peacebuilding called for in this volume, ‘the Mayan cosmovision fosters a holistic understanding of things, does not divide events, but rather emphasizes the interrelations among the psychosocial, the environmental and the cosmic towards an integral approach to people and reality’.

The dualisms that Reference BaradBarad (2007: 135) laments in much Western thought are absent from the Mayan cosmovision, which instead takes up what she refers to as the imperative of ‘thinking the natural and the cultural together in illuminating ways’, which means ‘not attribut[ing] the source of all change to culture, denying nature any sense of agency or historicity’ (Reference BaradBarad, 2007: 136). Reference BaradBarad’s (2007: 37) notion of agential realism is ‘about the real consequences, interventions, creative possibilities and responsibilities of intra-acting with and as part of the world’. In her work, she emphasises the importance of materiality, and the materiality of difference, how matter ‘matters’, and not merely as an effect of discourse. She emphasises the importance of ‘material agency, material constraints, and material exclusions’ (Reference BaradBarad, 2007: 34) and contests the discursive turn that dominated twentieth-century social science research and much feminist theorising. Indigenous and decolonial scholars embrace the focus on matter as do Mayan peoples.

Matter matters in the violence of colonisation and in resistance to it; as such it is foundational to Mayan expressions of resilience. The processes of colonisation violently turned the land into an object: ‘the territory was desecrated, that is, it was not sacred anymore, and became the land, a means of production that was supposedly inexhaustible and which was expropriated/exploited as never before, for the agrarian export of coffee, sugar cane and bananas’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 89). Decolonising the land means acknowledging its persistent agency, recognising its rights, re-centring it as living. In speaking about the demands of Indigenous people in Colombia for justice in the post-conflict transitions, Reference Izquierdo and ViaeneIzquierdo and Viaene (2018) describe an integral justice that transcends transitional justice processes to date, drawing on international legal norms, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) and the Colombian Decree 4633 of 2011, also known as the Law of Victims for Indigenous Communities.

The Decree affirms that rivers, mountains and the territories have rights, extending notions heretofore situated or instantiated in humans as distinct from other living beings. In the Colombian Decree 4633, land, rivers and territory are recognised as victims whose rights have been violated during the armed conflict and beyond when they were expropriated, desecrated or redirected. Territory is recognised as ‘a living whole and the sustenance of identity and harmony’ that ‘suffers damage when it is violated or desecrated by the internal armed conflict’ (Article 45). Decree 4633 also asserts that spiritual healing is part of the integral reparation of the territory (Article 8). Reference Ruiz SernaRuiz Serna (2017: 97) describes this recognition as implying ‘more rights of the territory than rights over the territory’.

Reference ViaeneViaene (2019) argues that both the state and NGOs who work in post-conflict pluri-cultural societies are challenged to problematise and re-conceptualise the dominant transitional justice paradigm such that they recognise, value and respond to Indigenous onto-epistemologies or cosmovisions. She notes that a key feature common to the Mayan cosmovision in general, and also to that of the Q’eqchi’ community whose work she has documented through over a decade of ethnographic research, is that ‘human beings must be understood as “relational beings”, which puts into question the dominant Western ontological division between culture and nature’ (Reference ViaeneViaene, 2019: 74). This worldview, in which everything is one, interrelated and interdependent, undergirds a non-dualist, collectivist materiality and spirituality that questions the anthropocentric approach to human rights and demands not only the recognition of collective rights but also the rights of the territory. This praxis echoes that of Indigenous peoples throughout Abya YalaFootnote 2 and beyond (Reference Esteva and PrakashEsteva and Prakash, 2014). They affirm their cosmovision as one among many, asserting that rather than a single universal principle or one declaration of universal human rights, we are challenged to open our minds and hearts to consider the pluriverse in which we live, struggle and affirm multiple cosmovisions, each of which is grounded in an onto-epistemology, a oneness of being and knowing.

In gendering their understanding of the Mayan cosmovision and contesting its patriarchal assumptions of gender complementarity – further evidence of the living iterations of these intersecting systems – Mayan women scholars and activists emphasise the gendered integrality of land and body in the experience of colonial violence and in resistance to it. Kaqchikel scholar Aura Reference CumesCumes (2012) argues that Mayan women challenge intersectional oppressions due to patriarchy, racism and class oppression from the margins of power, affirming their collective subjectivities through liberating emancipatory processes that reflect an integral ontology. Reference Chirix García, Leyva Solano and IcazaChirix García (2019: 140) notes that: ‘[s]ituating the body within a historical and political framework brings the memory of the invasion of the New World, the genocide, the process of inquisition and assimilation, and the imposition of a European, masculine and white model’. Indigenous women’s bodies were the systemic targets of violence, including rape, throughout centuries of colonisation, and Indigenous women connect the desecration of their bodies and the land itself. More recently, rape has been used by private security and state forces against women defending their lands from transnational corporate incursion (Reference Macleod and SiederMacleod, 2017; Reference RussellRussell, 2010). Indigenous women conceptualise the integrality of land-body-territory as the site of their resistance. Defining herself as a ‘community territorial feminist’, Mayan and Xinca activist Lorena Reference Cabnal, Leyva Solano and IcazaCabnal (2019: 121–122) notes:

Being an indigenous woman and defending our ancestral territory means putting on the front line of attack … our first territory of defence, the body. To defend the land territory, as women we conduct an impressive, parallel and daily defence in two inseparable dimensions: the defence of our bodily territory and the defence of our land territory … we recognize that the body as well as the land are spaces of vital energy that must function reciprocally.

In the following sections, we explore how diverse groups of Mayan women identify their resilience as persistence and protagonism as they too push the boundaries of Western-infused transitional justice praxis, seeking to defend land-body-territory in the wake of genocidal harm.

Mayan Women’s Voices Persist

Our dream is to gain more strength. Like the force of the blood that we carry, to maintain hope, so that the flower is produced that affirms our roots from which a large tree grows.

In reflecting back on her fifteen years of accompanying transitional justice processes in post-genocide Guatemala, Alvarez notes how the weight of the continuous wars, dispossessions, violences and oppressions that Mayan peoples have lived through has shaped their strategies of resistance, defence, struggle and resilience. Centuries of violence have informed what seems to be an underlying assumption that Mayan women and their communities are simply holding on or surviving in the face of an oppressive state and its actors. She is struck by how few voices there were that spoke of strength, power, the desire for life, rooted in the cosmovision and the capacities that have made it possible for Mayan peoples to persist and survive, co-constructing and protagonising their lives and histories day by day, building their territories based on self-determination. She notes that many of the words and phrases in these justice-seeking processes are in the coloniser’s Western language of a defence of rights, language promoted by international organisations that express the magnitude of the violence and the resilience that Mayan peoples have had to have in order to confront what they have lived through.

Those who have always engaged in these collective struggles for their communities, a key expression of Mayan resilience, are now called ‘human rights defenders’. While such language situates local work within an international context, it occludes the multiplicity of self-naming processes and actions of resistance, struggle, defence and creation, that is, the persistence in which Mayan women and men have always engaged. Alvarez highlights how, in talking to her sisters, they realised that these concepts of ‘struggle’ and ‘resistance’ do not exist in the K’iche’ language per se. Instead, there are several conceptions that they use within their cosmovision, including: Kakojachoq’ab’, ‘use your strengths’; Chatz’ukuj a kaslemal, ‘find the best way to live’; Chayik’a’a Kaslemal, ‘build your own life’ and Xojch’awoq, ‘let’s talk’.

As such, Alvarez takes up the challenge of how to strengthen Mayan identities and self-esteem that are grounded not only in pain and suffering, in past experiences of violence, but also in processes of healing and in expressions of pride for their cosmovision, for the life they have given the world. She reflects on the years she has spent working from within a Western paradigm while trying to recover her own ancestral cosmovision, ‘looking both ways’ to explain the complexities of violence that have shaped the lives of Mayan women and their communities while affirming the historical roots of Mayan experiences pre-Invasion. She notes that she has written much less frequently on the wonders recovered from the Mayan cosmovision, spirituality, ritual, biological logicFootnote 3 and the protection of life. Writing and focusing energy within this latter frame would enable new generations of women and men to love their Mayan identity, enjoy it and live it with happiness. As such, how can Mayan peoples not only focus their energies on the defence and struggle for their culture, their way of life, their body-land-territories, but also put into action affirmative ways of co-creating life, feeling and enjoying it in its integrality?

Healing processes have been an essential strategy in recuperating Mayan people’s vital strengths. Alvarez herself has drawn on her membership in the Grupo Mujeres Mayas Kaqla [Kaqla Mayan Women’s Group] (hereafter Kaqla), which brings together professional Mayan women who have worked to heal their traumas, including victimisation and sexual violence. The understanding of trauma they have articulated through multiple years of work is collective and transgenerational (Kaqla, 2011). Mayan women have lived through a continuum of political, social and familial violences whose sequelae need to be healed in order for them to reconnect themselves to life and well-being and not just to the wound itself. In its healing processes, Kaqla has brought together ancestral and Western techniques and methods to heal the traumas and effects of a continuum of racist, patriarchal and class-based violence and violations. These processes have enabled the members of Kaqla to recuperate and enjoy with much love their cosmovision, integrating and affirming their lived experiences and cultivating joy and well-being.

From 2012 to 2014, in her capacity as coordinator of the Women’s Rights Unit of the CALDH, one of Guatemala’s largest human rights non-governmental organisations (NGOs), Alvarez – together with other Mayan women – facilitated processes designed to strengthen the leadership of diverse groups of Mayan women that CALDH was accompanying in its human rights and justice work. Participants included women members of the Asociación para la Justicia y la Reconciliación [Association for Justice and Reconciliation or AJR] (the plaintiffs in the Ríos Montt genocide trial), the Flor de Maguey Collective (some of the women plaintiffs in the trial who had survived sexual violence during the genocide) and other Mayan women’s organisations who are defending their rights, including the Red Departamental de Mujeres Sololatecas con Visión Integral [Departmental Network of Sololateca Women with Holistic Vision], the Defensoría Maya Ch’orti’ [Ch’orti’ Mayan Defence Unit] and the Coordinadora de Jóvenes de Sololá [Sololá Coordination of Young People].

The training-healing-action-reflection workshops were structured to facilitate an exchange of knowledges. They sought to highlight the continuums of violences and resistances in the lives of Mayan women since the time of the Spanish invasion, with participants then becoming replicators of the workshop with women in their respective communities. They also published the book The Voices of Women Persist in the Collective Memory of their Peoples: Continuum of Violences and Resistances in Women’s Lives, Bodies and Territories (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014).

The process sought to reclaim a gendered understanding of historical memory that centred ‘the bodies and territories of women, as a common thread that gives meaning to individual experiences’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 172). The body-land-territory is identified as ‘the principal axis of women’s oppression and resistance; sexual violence, the usurpation of lands, territorial resistance, are cyclical dynamics that repeat throughout the history of humanity’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 53). The methodology’s onto-epistemology emphasised ‘the identification of violences and their sequelae but also the capacity for resilience that supports community resistance/persistence in the face of adverse situations’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 172). The workshops began from participants’ ‘lives, cosmovision, knowledge and power’ to make visible women’s ‘strengths and determination’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 172), which had been occluded by centuries of colonisation. Drawing on historical documents as well as participants’ testimonies and drawings and illustrated timelines, the process analysed the forms of violence against and resistance by Mayan women over six temporal periods, from the invasion to the post-war period.

In line with Reference TuckTuck’s (2009) aforementioned rejection of a focus on damage narratives, while the varied dimensions of colonial and militarised violence against Mayan women were highlighted, the workshops continuously excavated the multi-faceted forms of Mayan women’s resilience, framed here as persistence and resistance within and beyond local communities. As Alvarez notes and the book acknowledges, these examples were far harder to find but ever-present nonetheless, if one was willing and able to look for them. As one illustration, a persistent theme in the workshops was the constant occlusion of Mayan women’s agency and rights within their families and communities, as well as in the wider Guatemalan context.

The workshops’ embodied approach to historical memory drew on the work of the aforementioned Kaqla, which emphasises the integrated ‘affective, emotional, material and territorial’ aspects of memory, centres being as well as knowing, and recognises the body itself as ‘an entity that accumulates memory’ (Kaqla, 2004: 80). In taking such an onto-epistemological approach, ‘[h]istory and the history of our ancestors is written on our bodies, and as such it is imperative to integrate mind, body, emotions and actions’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 59). Various techniques and therapies from diverse psychological and healing practices (e.g., Advanced Integrative Therapy, Tapas Acupressure Technique, massage, Reiki, Chakras), as well as beliefs and practices from the Mayan cosmovision beginning with the Mayan calendar, were integrated into the workshops. These embodied processes were accompanied by group discussions, lectures, written exercises including participants’ ideas and reflections, exercises that included personal introspection to analyse participants’ particular realities, group dialogues and creative recreation, dance, painting, and singing as means to exercise the integrality of individual and collective voices. As the book articulates:

To be able to heal the wounds we have to know the shadows … When we talk about healing we are talking about returning to our centre and recovering our capacities, potentialities and internal resources and for this we use tools and techniques from the Mayan cosmovision, psychology and pedagogy, so that individually and collectively we can review and transform, recovering our powers and knowledges, understand our personal and collective histories.

The timeline of resistances generated in the workshops emphasised the important historical role played by the Ajq’ij, spiritual guides. Despite repeated attempts to erase their presence through centuries of colonisation, ‘they have maintained the knowledge of the sacred fire’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 154). As the timeline they developed highlights, today Mayan women and men are re-learning their spirituality, lighting incense and conducting ceremonies in sacred ancestral sites (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014). The role of Ajq’ij has also been taken up by Mayan women in many communities in their capacity as healers and midwives, known as ‘akanal in Ixil, ajkun in Kaqchikel and banonel in Q’eqchi’’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 154). In addition to having been in charge of most births in rural communities throughout the centuries, Mayan women have continued to cultivate and prepare medicinal plants and preserve and create new forms of knowledge to treat their communities (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014). The processes facilitated by CALDH revealed the importance of the recovery of the values of the Mayan cosmovision for Mayan women’s collective identity, allowing them to draw on their ancestral ways of living and being while centring themselves as women and integrating a relationship between past and present, thereby strengthening their persistence in resisting the colonial ‘logic of destruction’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 154).

Those who engaged in these training-healing-action-reflection processes and wrote the resulting book took great care to resist the damage frame as totalising, in part by interweaving forms of resistance to violence and presenting contrasting experiences over time, thereby excavating and embodying Mayan women’s persistence and resistance. This included the resilience of those who chose to participate as plaintiffs and witnesses in the 2013 genocide trial. As articulated in three publications by groups of Mayan women who took part in that trial, this thirteen-year process of organisation and endurance resulted in strengthened community networks and Mayan women’s enhanced protagonism (see CALDH and Grupo de Mujeres Tiilach’j Ixo’j, Mujeres Valientes 19 de Marzo, 2018; CALDH and Grupo de Mujeres Xu’m Saj Chee, Flor de Maguey, 2018; CALDH and Mujeres Asociación para la Justicia y la Reconciliación AJR Txu’mil, 2018).

Mayan women participants chronicled these multi-year journeys of self-discovery, valuing the group processes through which they voiced multiple experiences of previously silenced embodied suffering, standing up to publicly assert their rights as women, denouncing not only racialised war-based violations of their bodies but also contemporary gendered family violence and corporate extraction of natural resources in their territories. They ‘defied their own fears, showed themselves their strength, and created networks of support among women and with their communities’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 168). One trial participant noted how, ‘We are all together, like the butterflies, like the birds, in group, we are not alone, and thus we are on the path to justice’ (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014: 169).

Alvarez reclaims this process of coming together, of organising, of being in-community, as a central aspect of ‘justice’ itself, given a colonial judicial system that has not taken up Mayan people’s demands for historical justice. She highlights the multiple ways through which the processes of women coming together in healing processes are grounded in and lift up their contemporary iteration of the Mayan cosmovision, one that counters Western dualisms between the person and the environment, the cultural and natural worlds. It is significant that participants represent their resilience through the natural world, invoking the integrality of the human and natural worlds, as Crosby and Lykes also found in the creative workshops they facilitated, and which they examine in more detail in the following section.

Mayan Women’s Protagonism Takes Flight

[I am] old, without suffering, without fear and without shame. Today I am capable of doing all that I can. I am like a bird. I can fly with large wings.

Over a period of eight years (2009–2017), Crosby and Lykes facilitated a series of creative workshops with fifty-four Q’eqchi’, Kaqchikel, Chuj, Mam and Poptí women, including the fifteen plaintiffs in the Sepur Zarco case, who survived racialised gendered violence during the height of the genocidal violence in the early 1980s.Footnote 4 The work was initiated in 2009 in collaboration with the National Union of Guatemala Women (UNAMG, for its Spanish name) who had been working with these protagonists since 2003. Crosby and Lykes accompanied the fifty-four Mayan protagonists as well as the ladinx, mestizx and Mayan feminists, psychologists and lawyers working alongside them, documenting their journeys in search of redress.

They drew on creative techniques – drawing, image theatre, creative storytelling – as they interfaced or complemented Mayan rituals and practices (Reference Lykes, Crosby, Bretherton and LawLykes and Crosby, 2015). They facilitated action-reflection meaning-making processes through which participants individually and in small groups creatively represented their experiences in their search for truth, justice and reparations for the violations they had survived. They documented protagonists’ images, performances and interpretations, drawing on them to produce an approximation of how protagonists constructed meaning through their embodied praxis and dialogically with those intermediaries who accompanied them, Crosby and Lykes included (Reference Crosby and LykesCrosby and Lykes, 2019).

In this section, Lykes and Crosby re-situate several of the Mayan protagonists’ representations in the creative workshops to re-envision resilience in the wake of genocidal violence and ongoing gendered racialised violence in Guatemala. Reading protagonists’ images and performances from the ground of their onto-epistemologies, they aspire to ‘stand under’ them (Reference PanikkarPanikkar, n.d.), to resituate the matter that matters to these fifty-four Mayan protagonists as they perform and re-present their cosmovision. Their understanding is further informed by Mayan women’s theorising (see, e.g., Reference Chirix GarcíaChirix García, 2003, Reference Cabnal, Leyva Solano and Icaza2019; Kaqla, 2004, 2006, 2011) as they seek to avoid essentialising or romanticising these ways of hearing and seeing the natural world, Pacha Mama, Mother Earth, the only home any of us know. They seek, in the words of Reference BaccaBacca (2020: 143), to allow themselves to be ‘captivated by the [Mayan women’s] voices’, discerning how Mayan onto-epistemology re-centres the integrality of life, of body-land-territory, of being-knowing through agential realism.

They ground their analysis in gendered ways of seeing-being-knowing that deconstruct colonised racialisation of all the natural elements – water, earth, air and fire – affording them the same respect and dignity with which Western onto-epistemologies seek to treat human beings. Turning to the work of Kaqla, they note that this Mayan women’s group designed their workshops to recover human spirituality through creating spaces that promoted ‘spiritual connections with the Heart of the Sky, the Heart of the Earth, the energy of the universe, the divine light and universal love … we incorporate elements and practices of Mayan spirituality that respect diverse ideologies, practices and beliefs’ (Kaqla, 2006: 10). As Mayan women participants in a Kaqla workshop focused on their breath and their bodies, the facilitator noted that:

We remember our connection with the earth, with the subtle universe in the universal love. We connect and we feel the rivers of light that come out of the earth that is the nutritious energy of the earth, it comes up through our body from the feet to the head and it gives us nourishment. Everything else we let go of so that it goes toward the universe communicating with the earth through the sun, as a universal principle.

As Crosby and Lykes were beginning their research, they participated in a workshop with some of the fifty-four protagonists facilitated by the Peruvian theatre group Yuyachkani in the town of Chimaltenango, Guatemala. In the workshop, all participants were invited to stretch themselves out on newsprint while a partner drew the outline of their bodies. Participants were then invited to use pens and crayons and paints to represent their life journeys, including experiences, people or places that had brought them to this day in 2009. The drawings were then taped to the walls of the large room in which all were gathered, a space through which participants had moved through a variety of warming-up and breathing exercises before engaging in this individual drawing process.

Among the more than fifty images were the three below (see Figure 9.1). Participants were urged to speak with each other, analysing drawings as they passed by and then storying their own drawing for others to experience through looking and listening. Among the emotions were some that referenced sorrow, pain, suffering and physical wounds due to sexual violence, while others spoke of new life, rooted in Mother Earth. The left and centre drawings visualise images of life and growth that Crosby and Lykes would subsequently see repeatedly in the creative workshops that they facilitated with these same women. All three drawings visualise Mayan women’s guipiles (blouses) and cortes (skirts), some in more detail than others, yet all display these gendered cultural representations, seemingly affirming their Mayanness, in the midst of or despite the multiple assaults on their bodies represented in the left and centre images. An idealised or aspirational image of embodied hope, frequently expressed by many among the fifty-four protagonists in Crosby and Lykes’ research, and including the recovery of land, a home, flowers, the sun and a river that flows through one’s territory, persist in and through the drawings, in and through these Mayan women’s lives.

Figure 9.1 Mayan women visualise embodied suffering and resilience

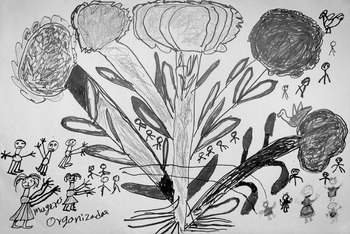

Many Mayan protagonists who participated in the creative workshops that Crosby and Lykes facilitated represented their lives through trees, flowers and seeds, life today, in the past and into the future. When they drew images of massacres or sexual violence, cornfields were burning and women’s bodies were thrown into rivers running through villages. When they represented themselves today, as seen in Figure 9.2, large trees had both roots and branches, connecting the past to the present in dynamic and living ways. Birds were often positioned above the branches, an image echoing the words of the Chuj protagonist in the above epigraph.

Figure 9.2 Mayan women represent life and growth and the integrality of humans and land

In one workshop in 2012, protagonists were invited to gather with others who spoke their language, given the absence of sufficient interpreters to facilitate cross-language communication, to discuss their experiences of ‘community’. After presenting the conclusions from these discussions to the group as a whole they were invited to develop a collective drawing to represent their community’s advances and setbacks over the previous years in which all had been gathering in these workshops. Each group then presented its drawing to the participants as a whole, who reflected on what they saw. One participant in the larger group noted that the drawing by the Chuj (see Figure 9.2) showed women who had begun to ‘clear the area, to water that tree, so now it has good roots and green leaves, now they can harvest, the tree bears fruit’. Others added that ‘when you plant a tree you have to water it, keep it clean, then there will be a harvest, advances’. A third participant noted that some of them had previously drawn wilted plants, contrasting those experiences with the now healthy tree that bears fruit and comparing the latter to an organisation that ‘plants a seed in the lives of women’ who then organise. This collective drawing peppers human images of women, men and children throughout, centring the human community around a strong tree trunk that bears flowers and fruit, with roots that spread widely in a variety of directions. The seamless integration of women, men, children, plants and birds, as well as the size of the environment and the diverse colours used to represent life and growth, suggest that humans are integral to or at one with the land, rather than having dominance over it.

Human beings are depicted throughout the image, with women and children on the right side dispersed, representing life before they began to organise, and contrasting with those on the left who are named as women organisers. These women had been in refuge in Mexico where they encountered the Mayan refugee women’s organisation Mama Maquín. Their reflections highlighted their suffering and displacement as well as the important ways in which they had learned to organise among themselves, lessons that they had brought back to Guatemala with them.

Other groups focused their drawings on advances and setbacks in their experiences of transitional justice, including their demands for truth and reparations, and noted the ongoing threat of the previous military commander of a scorched earth strategy in the Ixil area in 1981–1982, Otto Pérez Molina, who was running for the presidency of the country. Others focused more explicitly on the continuities of violence, emphasising the current violence of resource extraction by transnational mining companies because ‘they are taking gold, wealth out of our country. They are destroying trees and contaminating water, and what will we leave our grandchildren?’ A Q’eqchi’ woman from the Polochic Valley noted that ‘the government is giving everything to the rich, they are evicting people from the land, they send security for the rich and pay no attention to our needs’.

Another participant explained that ‘in our pictures we put what comes to mind. But not everything comes to mind, like mining. It brings disease, contaminates water. This is the government’s plan, it wants to damage Guatemala, the environment; it wants to harm the people. We as Indigenous people have to ask ourselves what to do. We are saying no to mining, but every government wants it’. Finally, after noting that these national challenges play out in varied ways given local leadership, one participant described things in the country as ‘worrisome’, adding that engineers had come to her community, saying that they were doing a study. She noted that her community still had forests, wooded areas and rivers, and some community members concluded that since the engineers seemed to be examining the river, it would appear that they wanted to put in a hydroelectric plant. She asked: ‘What will become of our children if they contaminate the river?’ Others added that plantation owners were planting African palm in their community, generating significant worries among the women as ‘it contaminates the river’.

Protagonists described multiple significant changes grounded in their deep knowledges of their and their communities’ histories; multi-systemic dynamics that reflect continuities of colonial violence and expressions of persistence and protagonism within and across these systems; resilience that they attributed to their many years of organising for their rights in the wake of genocidal harm – and through which they had learned about their rights to body-land-territory and overcome their fears of speaking, even being willing to speak up in the trial of their assailants. Yet, in describing the desecration of their lands, of their territories, that they positioned as a continuity of the violence against their bodies, they once again felt threatened, noting in this 2012 workshop: ‘This worries us, we don’t know what to do. The rich have weapons and they intimidate us. What if they do come in, they are supported by the government. What are we going to do, we don’t know what to do’. Despite the dynamic and iterative systems of resilience, they recognise the lack of resources adequate to contest state colonialism and multinational neoliberal capitalism.

Looking across these and many other engagements with different configurations of these fifty-four women in the workshops that they and others have facilitated, Crosby and Lykes note the various representations of the continuities and continuums of violence, the ongoing systems and structures that took root during colonisation over 500 years ago. As Alvarez and her colleagues (Reference PérezCALDH and Pérez, 2014) argue, drawing on the action-reflection processes discussed in the previous section of this chapter, Mayan women not only understand those continuities but also embrace the stories of their ancestors and embody their beliefs and practices as they are reinterpreted through their multiple Mayan groups, geographically based communities and communities of women.

What persists are the deeply threaded intersections of land-body-territory, the recognition of and respect for humans who travel among other living beings – rivers, mountains, animals, among them – and who have contended for centuries with colonial powers that had fractured what Mayan peoples experience as an integral whole. One experience of healing can be achieved when humans care for the rivers and mountains that are one with them, as they drink from them and walk in their midst (Reference ViaeneSieder and Viaene, 2019). The gendered and racialised transformative praxis of healing described herein is embodied and performed at the intersections of land-body-territory, an intersection represented by persistent Mayan protagonists through the images and words of the processes recounted in this chapter. Their resilience has been documented by those who have accompanied them through multiple years of praxis framed, facilitated and constrained by processes of transitional justice. Despite the latter, the creative techniques, Mayan cosmovision and other healing processes described above facilitated processes through which differently positioned intermediaries have approximated an understanding of these alternative forms of justice that centre Mayan resilience.

Conclusion

Key components of the emerging paradigm of adaptive peacebuilding, proposed in this volume as representing a new direction for transitional justice, include a shift in focus from ends to means and an emphasis on ‘strengthening the resilience of local social institutions and … investing in social cohesion’ (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 304) – what some in the transitional justice field refer to as transformative justice or justice from the ground up (Reference Gready and RobinsGready and Robins, 2014; see also Lambourne, Chapter 2). The strengthening of the Guatemalan judicial system that saw the undermining of the entrenched, systemic impunity for human rights violations was made possible because of the resilience of the country’s Mayan majority accompanied by organised civil society who have persisted in and protagonised the struggle for justice in the context of an increasingly (re)militarised, corrupt and violent state.

The struggle itself has strengthened a civil society fractured and fragmented by decades of armed conflict, supported the emergence of an independent judiciary led by key figures such as former Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz Bailey, consolidated an Indigenous movement focused on territorial defence of land and body, and facilitated processes through which significant numbers of Mayan women protagonists have asserted their rights, defying patriarchal, racialised, colonial power. However, as we have argued in this chapter, the short-term ahistorical strategies of transitional justice deployed therein have failed to respond to the sequelae and continuum of the centuries-old and continuous genocidal harm for which Mayan women and their communities seek historical justice.

For transitional justice to contribute to developing the adaptive capacity, resources and resilience of individuals, communities and social and political institutions in post-genocide Guatemala, it must recognise the continuation and continuum of violations of the rights of Mayan peoples and their territories for over 500 years. It must support locally driven, community-oriented processes that repair the historical damage incurred to their lands, bodies and cosmovisions. It must foment a justice that returns to Mayan peoples that which has been plundered and expropriated from generation to generation. The justice mandated is one where the bodies of Mayan women are not subject to any type of violence, where Mayan peoples are not undervalued, racialised or pathologised as essentially damaged, but, rather, where their dignity is affirmed and their millennial cosmovisions are recognised as reflecting a valued way of life through which they have persisted against all odds. As we have argued in this chapter, Mayan women demand a justice that integrally addresses the intertwined rights of land-body-territory, the ongoing defence of which is a key expression of their resilience.

Throughout centuries of colonial violence, Mayan women have persisted, sustaining life, caring for new generations – planting their land, feeding their families, weaving their clothing and healing their wounds. While the Guatemalan state, as well as internationalists, NGOs and human rights activists, have turned towards Western legal systems, Mayan women have known that their ancestral paradigm has sustained life. As with the work of Kaqla, those we have accompanied have also taken and integrated the good from other paradigms. As such, it is not an essentialised notion of Mayanness that they seek, embody and perform. Their ancestors adapted to survive, and the multiple forms of living from which the Mayan women whom we have accompanied continue to draw as they seek well-being reflect an embrace of the pluriverse, a recognition of diverse ways of knowing-being. They affirm and transform their ancestral cosmovisions wherein life reflects an integration of energies, emotions and spirituality from within a respect for all within existence, human and non-human. They seek to recuperate kamowaj, the process of giving thanks, which is rooted in daily rituals practised with seeds and animals, with the network of life and Mother Earth.

The processes described in this chapter through which Mayan women perform persistence and protagonism as expressions of resilience validate the memory of Mayan peoples and their ongoing search for historical justice. They narrate pain but, as importantly, affirm and celebrate their resilience, in forms of well-being, of partnerships, of sexuality, of plantings, of nourishment, of spirituality and of the care for and protection of all of life through their languages and from within their onto-epistemologies. Those of us who are invited to accompany these processes are challenged to collaborate in forging the necessary conditions and mechanisms that support the recuperation of territory and the common good, and, as such, we need to go beyond transitional justice, state justice and externally imposed forms of peacebuilding. Although still a legitimate – even necessary – demand, not all vital energy must be consumed by it. We must conceive resilience otherwise, whether as Kakojachoq’ab’, Chatz’ukuj a kaslemal, Chayik’a’a Kaslemal, Xojch’awoq, or the multiple Mayan conceptualisations of resistance and struggle, while affirming, as they do, the pluriverse within which their cosmovision persists.