Introduction

The rise in childhood obesity, being overweight, nutrient deficiency and the concomitant increase in associated non-communicable diseases is an area of particular concern for health authorities(1). Obesity during childhood and adolescence is a complex phenomenon, metabolically driven by energy imbalance, but resulting from a combination of multiple individual and societal factors interacting (biological predisposition, socioeconomic and environmental factors) within a structure that creates the conditions that promote and perpetuate obesity(Reference Kansra, Lakkunarajah and Jay2,Reference Jebeile, Kelly and O’Malley3) . Children need to eat varied balanced diets to be in good health, to prevent the development of obesity, but just as importantly, to establish healthy eating behaviours that are sustained in later life(Reference Arimond and Ruel4–Reference Molani Gol, Kheirouri and Alizadeh8).

The determinants of eating habits are multiple, including personal factors related to the individual (physiological factors and phenotypes; e.g. satiety, sensory sensitivity and taste acuity, psychological; e.g. emotions and psychological traits, preferences and food literacy competencies), as well as characteristics of the food environments and food supply chains(Reference Raza, Fox and Morris9). Several models and reviews have summarised the multiple factors underlying food choices, which are differentially relevant to adults and children of different age groups (for example, see Leng et al. 2017(Reference Leng, Adan and Belot10) or Perez-Cueto, 2019(Reference Perez-Cueto11)). More recently, the need to go further than individual determinants, adopting a system’s thinking to children and adolescents’ diets has been stressed by both academia(Reference Raza, Fox and Morris9 , Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender12) and international organisations(Reference Keeley, Little and Zuehlke13). Food systems can be defined as: ‘all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the output of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes’(14). Food systems thinking can be particularly useful to decision makers for promoting health by recognising the interconnectedness of food, the environment and human subject health, in the design of policies and multi-level interventions(Reference Brouwer, McDermott and Ruben15), for example through combined community-based, school-based and family-based interventions.

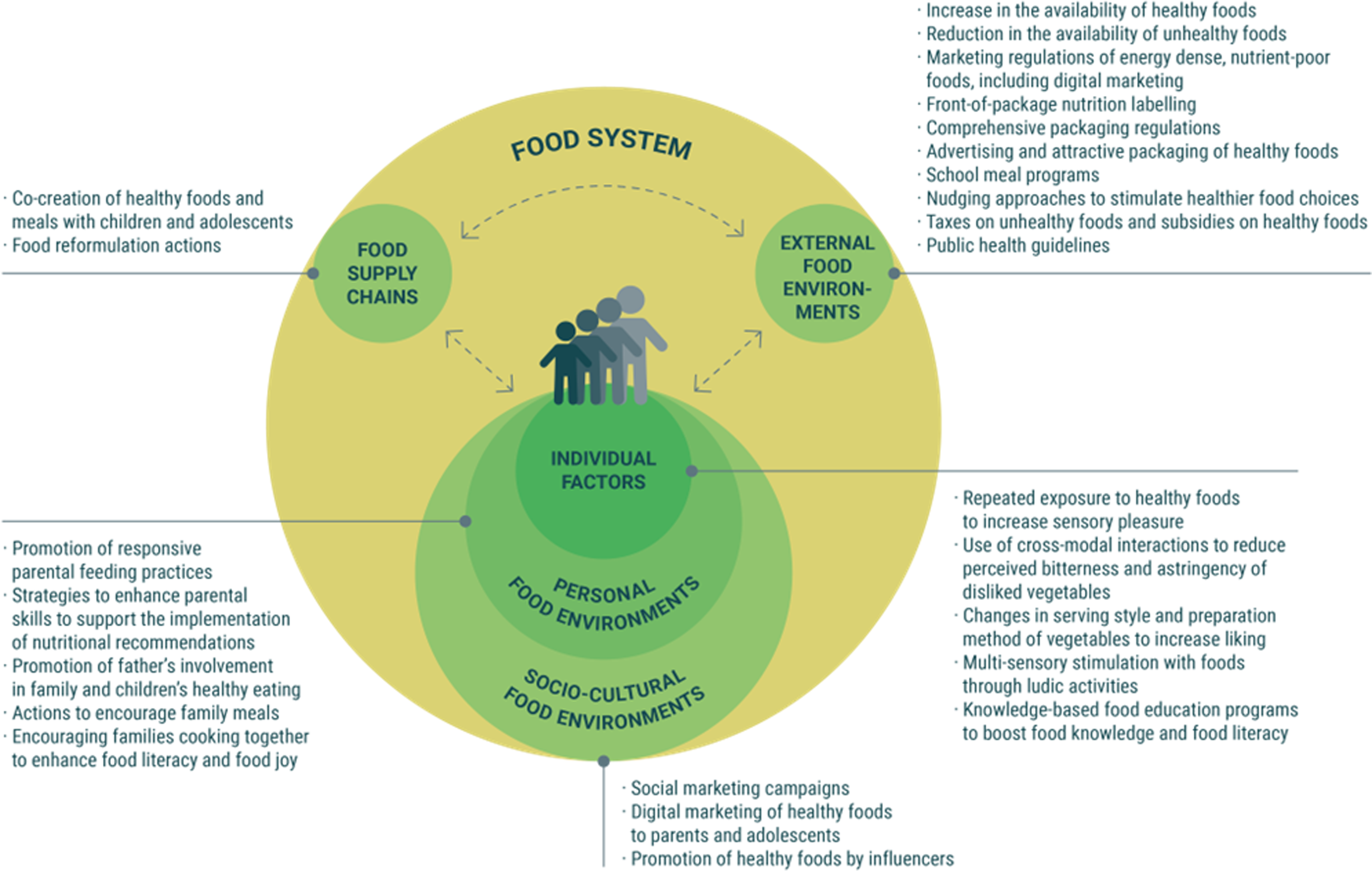

The objective of this review is to describe promising approaches, within a food system perspective, to foster healthy eating in children and adolescents. A food system perspective considers the entire food supply chain, from production to consumption, and the economic, social and environmental factors that shape food choices. Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to unhealthy food environments due to their limited decision-making power, exposure to advertising and peer influences. Therefore, it is crucial to identify multilevel evidence-based interventions that can promote access to healthy foods, provide nutrition education and encourage healthy eating habits to reduce the prevalence of diet-related diseases and improve overall health outcomes in this population. We define a healthy diet as per the WHO definition(16) (WHO, 2020), focussing on the promotion of multiple parameters: encouraging the consumption of fruits and vegetables, promoting food reformulation (e.g. sugar reduction) and other strategies discouraging the consumption of non-core foods (e.g. marketing and labelling regulations). We give a summarised picture of the food systems from the point of view of the child, to guide us through the main influencing factors that will be discussed: individual factors, factors within the personal and socio-cultural food environments, and the influence of the external food environments and the food supply chain. In each section, main barriers will be briefly discussed focussing on how to overcome them. Finally, a general discussion with recommendations is provided. We focus mainly on preschoolers to adolescents, but some references are given related to other developmental stages when relevant to the discussion.

Rather than a systematic review, this narrative review is the result of a collaboration within the European Union-funded project Edulia (www.edulia.eu), that aimed to bring down barriers to children’s healthy eating from an interdisciplinary perspective, with a strong focus on training and capacity building, generating numerous research papers and eleven PhD theses. As such, the basis of this review is multiple literature reviews, scientific workshops and discussions among researchers of different areas, that may be reflected in the selection of and emphasis given to some of the main factors reviewed.

Children and adolescents as central actors in the food system

A conceptual framework based on food systems (depicting the relationship between the variables and mapping out how they interact) can provide better understanding of how the eating habits of children and adolescents are shaped, enabling the identification of key multisectoral approaches that should be implemented to promote healthier diets(Reference Raza, Fox and Morris9). Fox and Timmer (2020) proposed a socio-ecological framework of the interactions of children and adolescents with the food system, highlighting that they are not a homogeneous group and that age-specific characteristics will shape how they engage with the system, as active agents(Reference Fox and Timmer17). Socio-ecological models consider the interplay of factors across all levels of health behaviour, acknowledging the complexity of public health issues that require a multi-level approach(Reference Townsend and Foster18).

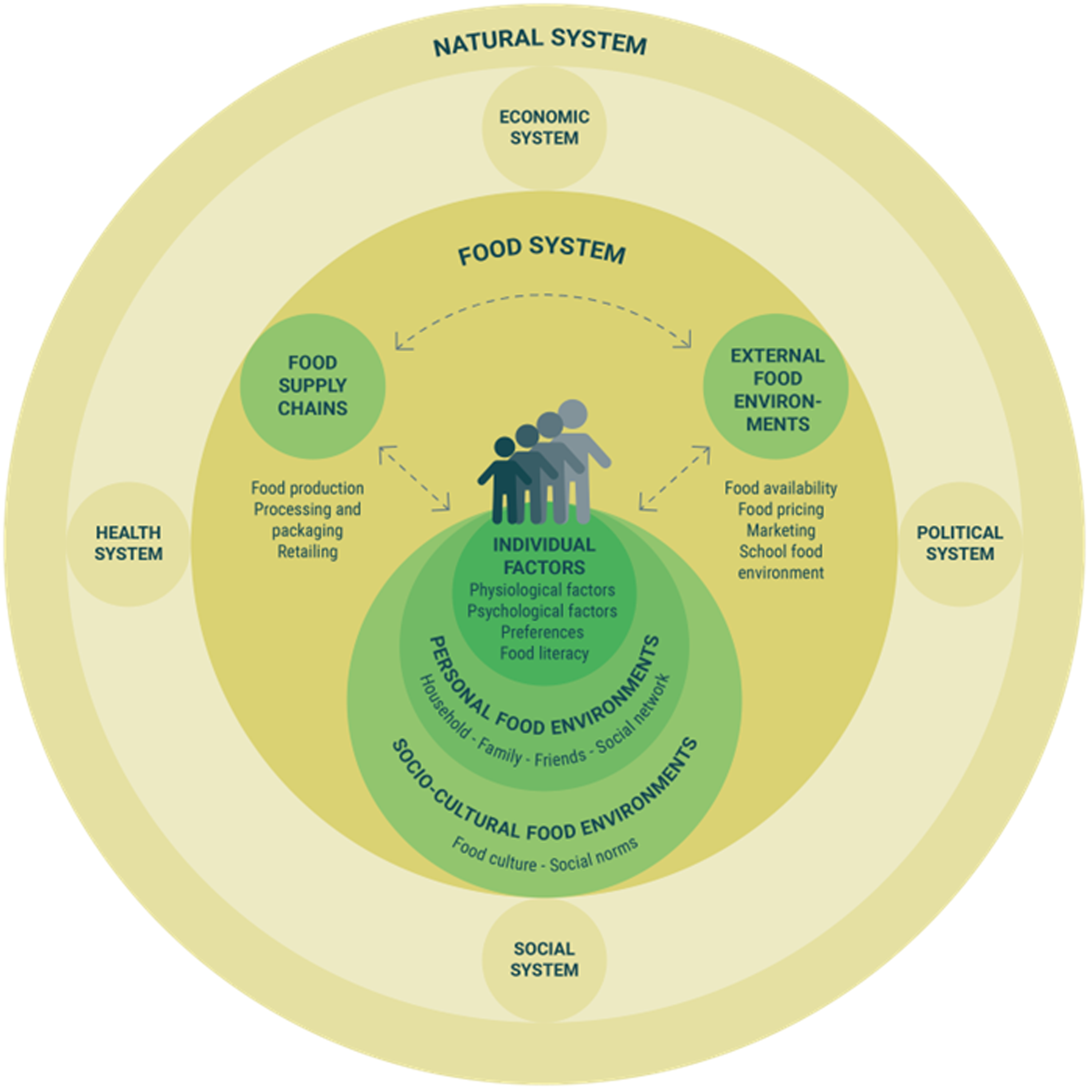

The Innocenti Framework for food systems and children’s and adolescents’ diets(Reference Raza, Fox and Morris9) defines the elements of the food system as the sum of the drivers (processes and structural factors), determinants (processes and conditions), influencers (immediate and individual-level factors) and interactions. The Innocenti Framework is composed of four determinants: food supply chains, external food environments, personal food environments and behaviours of caregivers, children and adolescents. The food environment comprises: ‘the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural context in which consumers engage with the food system to make their decisions about acquiring, preparing and consuming food’(14).

In Fig. 1 we propose and adapt a framework, depicting how the eating habits of children and adolescents are shaped by the different components of the food system, with a focus on children and adolescents as central participants. We start from the definitions of the elements of the food system from the Innocenti Framework, integrating some of the socio-ecological model concepts from Fox and Timmer (2020)(Reference Fox and Timmer17), further differentiating amongst the types of food environments based on the relation and influence that the child has as an active part of the system.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of children and adolescents as an active part of the food system

External food environments, which the child has no to low influence on, reflect aspects related to the availability of food in the retail environment, food pricing and food marketing, including the school food environment. Those aspects closer to the child include personal food environments, which comprise individual and household characteristics that determine access to food–household food availability, and the interaction of children and adolescents within their family, but also other close social actors like friends and teachers – as well as broader social elements, namely the socio-cultural food environments, including food culture, social norms about food and social media, that further influence how children relate to food. Personal and socio-cultural food environments closely interact with and influence the child’s individual factors such as food preferences and food literacy. Finally, the food supply chains include the actors and activities related to food production, storage, distribution, processing and packaging, which also influence children and adolescents’ eating habits by determining the characteristics of the foods available in the marketplace.

At different developmental stages, factors will have different weights in shaping children’s and adolescents’ preferences and diets. At an early age, the personal food environments will largely influence eating patterns through household food availability and parental feeding practices(Reference Birch, Savage and Ventura19). As children grow, external food environments, particularly the school food environment and food marketing, will have a larger relative importance on what and how children eat(Reference Neufeld, Andrade and Ballonoff Suleiman20). Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that external food environments (e.g. access and availability in their area) and socio-cultural factors may also influence preferences to some extent even at a young age. The transition to late childhood and adolescence can bring new challenges, with increased independence from parents and stronger peer influences(Reference Birch, Savage and Ventura19). Social media, food marketing and influencers may increase the social pressure towards poor diets, and an adolescent’s desire for agency and singularity may push them further towards unhealthy diets(Reference Neufeld, Hendriks, Hugas, Von Braun, Afsana and Fresco21).

It should also be highlighted that the food system is not isolated, but interacts with other complex systems created by humans, such as the economic system, the political system, the health system and the social system, and also with the natural system, in which all food-related activities are embedded(Reference Westhoek, Ingram and Van Berkum22). These other systems will not be discussed in depth in this article. However, this complexity stresses the need to implement multi-level approaches, simultaneously involving various components of the systems, including community-level interventions, social marketing, education, parental feeding practices and regulations to trigger changes in the external food environments(Reference Hoelscher, Kirk and Ritchie23).

Empowering children as drivers of their own healthy eating: individual factors

In this section we discuss different approaches to children and adolescents’ individual factors, with a focus on aspects driving food choices that may be modulated through interventions. Firstly, we address physiological (e.g. sensory perception) and psychological aspects (e.g. food neophobia) and strategies to modulate food preferences (e.g. repeated exposure), highlighting the importance of pleasure to foster healthy eating. Secondly, we address food knowledge (e.g. nutrition, food combinations) and food literacy, highlighting the importance of factual, relational, critical and functional competencies to empower children as drivers of their own healthy eating.

Driving healthy eating through sensory pleasure

Sensory pleasure is the main driver of children’s food choices(Reference Schwartz, Scholtens and Lalanne7), and it is therefore important to emphasise the hedonic aspect in healthy foods to increase their intake. Our senses play an indispensable role to perceive and respond to information about our surroundings. Each sense (sight, smell, hearing, touch and taste) provides different information which is processed and combined by our brain to create a complete sensory picture. Eating involves all our senses, which act in two important ways: on the one hand they can prevent us from eating potentially harmful substances, and on the other hand they can stimulate our appetite when a food looks appealing or smells good(Reference Boesveldt, Bobowski and McCrickerd24). The stimulation of our senses is an important determinant of whether we decide to eat and whether we enjoy eating the food or not. However, the protective mechanisms of the senses can often pose a barrier to children’s healthy eating due to the rejection of unpleasant sensory properties(Reference Rozin25,Reference Laureati, Sandvik and Almli26) .

To promote healthy eating in children it is important to develop strategies to increase sensory pleasure as part of the eating experience, including the emotions elicited by food sensory properties(Reference Spinelli and Meiselman27). The research on emotions during food experiences has expanded considerably in the last decade, including the development of age-specific new methods to assess emotions(Reference Sick, Spinelli and Dinnella28–Reference Sick, Monteleone and Dinnella30).

Some sensory properties may pose a barrier for children to eat certain foods and were found to elicit negative emotional responses. For example, bitter taste is innately rejected as it signals that the food can be potentially harmful(Reference Rozin25). Recent research showed that sensory pleasure/displeasure in response to food already starts at prenatal stage, as fetuses respond with pleasant (carrot flavour/sweet taste) and unpleasant (kale flavour/bitter taste) facial expressions to chemosensory information conveyed by flavour/taste compounds in the maternal diet(Reference Ustun, Reissland and Covey31). Furthermore, sensory pleasure from food is learned during childhood through early eating experiences and exposures(Reference Nicklaus32). For instance, specific flavour exposure in utero and post-natal exposure to a flavour through breastmilk have been shown to increase the liking of a particular flavour later in life(Reference Spahn, Callahan and Spill33). A further effective strategy to increase food acceptance and food pleasure during childhood is repeated exposure, in which children are exposed to a specific taste, flavour, texture or food multiple times, gradually enhancing the pleasure that derives from their consumption. Thus, children can learn to develop pleasure from the sensory properties of foods even when the food is initially disliked(Reference Maier, Chabanet and Schaal34). Repeated exposure has been shown to be a promising strategy to establish healthy eating behaviour in children and could be applied both at home and in school canteen settings. The simultaneous or sequential presentation of food items has also been found to influence food intake based on the principle of hedonic contrast(Reference Zellner, Rohm and Bassetti35). Regarding simultaneous presentation, food stimuli are rated as less good when presented together with very good context stimuli, than when presented either alone or with a neutral context stimulus. A practice to encourage vegetable consumption in school children based on sequential presentation of food items includes serving the fruit component (that is generally liked) after the rest of the meal, not together with it(Reference Zellner and Cobuzzi36). In fact, when fruit was served together with less-liked vegetables (hedonic contrast) the consumption of vegetables was lower, as children favoured the fruit instead.

An increasing amount of research focusses on strategies to increase the enjoyment of eating healthy foods and overcome unpleasant sensory properties in children. Strategies to increase healthier foods can be based on the reduction of “warning” sensory properties, for example reducing bitterness and astringency of vegetables by masking these sensations through sensory interactions with other sensory properties in a dish or a meal. Sweetness suppresses bitterness, and the mixture of sweeter healthy ingredients (e.g. carrots, pumpkins and peas) with more bitter vegetables may be used to promote the acceptability of the latter. Studies on the development of healthier food and meal solutions that profit from the sensory interaction mechanisms are encouraged (further discussed in Section 4·4). Added to this, as children differ widely in their taste sensitivity and preferences(Reference Ervina, Almli and Berget37), the development of tailor-made food solutions is encouraged. For example, Ervina and colleagues (2021) reported that sucrose addition is an efficient suppressor of sourness and bitterness in preadolescents highly sensitive to sweetness and poorly sensitive to sourness and bitterness, but not in subjects with opposite responsiveness traits.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that children often dislike the hard and rough texture of some vegetables (such as broccoli or cauliflower), and that ‘hard-liker’ children eat vegetables more frequently than ‘soft-likers’(Reference Laureati, Sandvik and Almli26). These individual differences may stem from different mouth behaviour groups characterised in adults as ‘chewers’, ‘crunchers’, ‘smooshers’, and ‘suckers’(Reference Jeltema, Beckley and Vahalik38), or from mouth physiology groups based on particle-size sensitivity, biting force, saliva flow rate and chewing efficiency(Reference Kim and Vickers39). Moreover, exposure to textures at a young age, such as during weaning impacts oral physiology development and acceptability of textures(Reference Nicklaus, Demonteil, Tournier, Chen and Rosenthal40). It should also be noted that culinary traditions across cultures may lead to differences in familiarity for different textures (e.g. serving raw or cooked carrots)(Reference Laureati, Sandvik and Almli26).

Individual differences among children go further than sensory aspects. For example, food neophobia – a psychological trait defined as the reluctance to eat new foods – decreases with age but is higher in some children than others(Reference Lafraire, Rioux and Giboreau41). Neophobia is associated to lower liking and consumption of vegetables, fruits and a variety of other foods(Reference Proserpio, Almli and Sandvik42) and reduced dietary variety, representing a strong barrier to changing eating practices. For instance, it has been shown that children who have a lower liking for tactile stimulation or tactile play are more likely to display greater picky eating(Reference Nederkoorn, Jansen and Havermans43) and score higher in food neophobia(Reference Coulthard and Sahota44). Tactile exposure to food can thus be an effective strategy to promote food acceptance and help to overcome neophobic traits. Specific strategies should also be developed considering food neophobia to develop products and meal solutions that may be accepted by neophobic children.

Some studies have proposed strategies to increase children’s vegetable consumption by considering the serving style(Reference Olsen, Ritz and Kramer45) and preparation method(Reference Zeinstra, Koelen and Kok46) to increase the appeal of sensory properties of vegetables. Olsen et al. (2012) investigated serving styles of raw snack vegetables and found that the shape and size influenced the liking of vegetables; 9–12-year-old children preferred having their vegetables cut in figures (compared with slices and sticks), and when serving whole/chunk vegetables, children preferred the ordinary size(Reference Olsen, Ritz and Kramer45). Zeinstra et al. (2010) found that Dutch children as well as young adults (4–8 years old, 11–12 years old and 18–25 years old) preferred boiled and steamed vegetables over other preparation methods (mashed, stir-fried, grilled and deep-fried)(Reference Zeinstra, Koelen and Kok46). Cutting vegetables in shapes or changing the preparation method of healthy foods can be relatively easily implemented by parents, caterers and producers (e.g. food industry) alike. The preparation may require some additional time, but it is a very cost-effective strategy.

Boosting food knowledge and food literacy

Food knowledge and food literacy can potentially counteract food rejections and allow informed decisions, supporting autonomous healthy and sustainable food choices. It is therefore important to build up these competencies in childhood. Food rejections (food neophobia and picky/fussy eating) represent one of the main psychological barriers to healthy eating in young children from 3 to 6 years of age(Reference Lafraire, Rioux and Giboreau41). Addressing barriers to healthy eating in children requires determining the origin of these food rejections or at least determining the factors that might predict their intensity. Recent studies demonstrated that children exhibiting intense food rejection were also characterised by poorer conceptual knowledge about food(Reference Rioux, Picard and Lafraire47). These studies represented a turn in the way to tackle eating difficulties in children, favouring the idea that food knowledge matters when it comes to facilitating healthy eating in children. In a nutshell, the more knowledgeable children are about food, the more willing to widen their diet and consider healthier alternatives. This motivated researchers to test an alternative way of designing interventions aimed at fostering dietary variety, the so-called knowledge-based food education programmes. These programmes do not seek behavioural change per se but aim instead at improving the conceptual apparatus of young children, to impact food behaviour and preferences positively and more sustainably by providing new facts about food(Reference Thibaut, Nguyen and Murphy48). These facts present foods as a source of nutrients combined with causal/biological explanations to help children to understand food and body relationships(Reference Gripshover and Markman49). In so doing, proponents of these interventions aim to tap into children’s naïve theories on biology(Reference Inagaki and Hatano50). Pickard et al. (2021) evidenced that a type of food knowledge distinct from nutritional knowledge and knowledge of food groups (e.g. fruits, vegetables, dairy, etc.) was related to food rejection in young children(Reference Pickard, Thibaut and Lafraire51). Indeed, children exhibiting intense food rejection (especially neophobia) were characterised by gaps in thematic and script knowledge. Thematic and script knowledge are, respectively, the knowledge of conventional or complementary food combinations (e.g. peanut butter and jelly, soldiers and boiled egg, strawberries and cream), and the knowledge of food-related contexts or events (e.g. breakfast, dinner, Thanksgiving, Christmas)(Reference Pickard, Thibaut and Philippe52). The development of these types of contextual knowledge is pivotal in the expression of food preferences and food rejection in children. In other words, food knowledge is not restricted to knowledge about food but embeds knowledge of food associations, as well as knowledge of food-related contexts or events which are highly culture-dependent. Therefore, future knowledge-based food education programmes should incorporate these contextual or cultural pieces of knowledge to positively impact children’s diet. Such an analysis is consistent with recent findings showing that one major obstacle to adding nutritious alternatives to the breakfast repertoire lay in children’s poor conception of what breakfast food should be(Reference Bian and Markman53). Moreover, breakfast has been discussed as an unexplored opportunity for increasing the total daily vegetable intake in children, in the UK and other countries where vegetables are not traditionally served for this meal(Reference McLeod, Haycraft and Daley54).

Further to food knowledge, food literacy programmes implemented in adolescents have typically targeted increased practical cooking and/or food preparation skills, as well as increased food safety and nutritional knowledge(Reference Brooks and Begley55,Reference Bailey, Drummond and Ward56) . Despite reported evidence of positive outcomes, there is limited evidence supporting an effect of food literacy interventions on long-term dietary behaviours in adolescents. Recent literature highlights food literacy as a wider concept than knowledge and skills, encompassing the acquisition of relational (emotional and cultural competencies to establish positive relationships with food, including the ability to enjoy food), critical (information and understanding) and functional competencies (knowledge, food-related skills and abilities)(Reference Truman, Lane and Elliott57). Thus, food literacy is an important concept that acknowledges children and adolescents as active participants in the food environment. It comprises the competencies needed to make healthy and sustainable food choices, as well as to act as drivers of change towards the transformation of food systems. However, there is still scarce literature addressing the long-term effect of increasing food literacy in children and adolescents on health and diet-related outcomes, representing a great opportunity for future research.

Supporting healthy diets within children’s personal and socio-cultural food environments

This section discusses approaches that tap into children’s and adolescents’ personal and social food environments, particularly focussing on the interaction within their family (parents, siblings) as well as with other social actors, such as peers within the school environment.

Strategies for parents to enhance healthier eating

The decisions that parents and family make regarding their child’s eating environment, such as food availability, types and amounts of food served, play a crucial role in shaping their child’s eating habits and establishing a particular food culture in the home, which can have a lasting impact on their child’s lifelong eating behaviours. From a general socialisation perspective, (i.e. the process of acquiring socially relevant knowledge and skills to become a well-functioning member of the society in which one is brought up), parents are believed to be the primary and most important socialisation agents(Reference Maccoby, Grusec and Hastings58). Furthermore, several studies have pointed to the pivotal influence of parents in relation to food socialisation(Reference Ventura and Birch59), for learning consumption-related skills, attitudes and behaviours, including healthy eating behaviours(Reference John60,Reference Moore, Wilkie and Desrochers61) . In the context of the family, eating habits are established through repetitive actions occurring at specific times, settings and with specific environmental cues(Reference van’t Riet, Sijtsema and Dagevos62). This points to the importance of the regularly occurring family meal for healthy eating socialisation. Indeed, adolescents’ frequency of eating a family meal has been associated with higher fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Granner and Evans63) and higher nutritional quality in general(Reference Dallacker, Hertwig and Mata64).

There are several fundamental parental determinants of eating behaviour, such as: parental attitudes (i.e. relatively enduring evaluations that parents have towards parenting), parenting food practices (i.e. the specific behaviours that parents use when feeding their child(Reference Scaglioni, Salvioni and Galimberti65,Reference Balantekin, Anzman-Frasca and Francis66) ) and parenting feeding styles. Generally, parenting styles reflect the parents’ demandingness (i.e. imposing structure and setting limits) and responsiveness (i.e. supporting autonomy and adapting to the child’s cues) and have been categorised into four patterns: authoritative (high demandingness, high responsiveness), authoritarian (high demandingness, low responsiveness), permissive (low demandingness, high responsiveness) and neglectful (low demandingness, low responsiveness), where the authoritative style has been associated with greater positive dietary outcomes in the long term(Reference Balantekin, Anzman-Frasca and Francis66,Reference Monnery-Patris, Rigal and Peteuil67) . Such positive feeding styles include caregiver responsiveness to children’s feeding cues, which refers to providing prompt and developmentally appropriate responses to hunger and satiety cues(Reference Di Santis, Hodges and Johnson68).

Parental feeding practices are strategies that parents use to influence their children’s eating behaviours and food choices, some desirable (e.g. structure and autonomy support) and others undesirable (e.g. coercive practices), sometimes stemming from the challenges parents face in achieving their desired goals for their child’s eating habits and growth. These practices involve controlling the quantity, type and timing of food intake and may be employed by any caregiver responsible for feeding the child. Feeding practices high in structure and autonomy support can support children’s healthy eating. Structure-based food parenting practices include for example feeding routines (e.g. family meals) and the provision of foods (e.g. availability and accessibility of healthy foods), whereas autonomy supportive food parenting practices include encouraging healthy intake and social modelling(Reference Balantekin, Anzman-Frasca and Francis66). Other positive parenting practices for encouraging healthy eating habits include repeated brief tastings of disliked or unfamiliar foods in a positive social context, using non-food rewards such as tokens or verbal praise, and avoiding excessive coercion or restriction while exerting positive control over the availability and portion sizes of healthy foods. It has been shown that the types of foods parents consume and make available to their children predict their children’s eating patterns. Both adult and peer models have been found to influence children’s acceptance of novel foods or bitter vegetables, indicating that social facilitation impacts children’s intake patterns(Reference Ventura and Worobey69,Reference Edwards, Thomas and Higgs70) . Positive interpersonal interactions and communication during mealtimes have been associated with healthier intake among children and adolescents(Reference Smith, Saltzman and Dev71). Restriction, use of food rewards (e.g. sweets) or pressure to eat may work effectively at meal level but are counterproductive over time at dietary level as they may result in heightened preference for the forbidden and reward foods, and lowered preference for the compulsory foods(Reference Gibson, Kreichauf and Wildgruber72). These strategies also lead to problematic systemic changes such as eating in the absence of hunger and inability to self-regulate appetite and diet. This may in turn impact children’s adiposity. Parental control of a child’s diet may lead to increased adiposity(Reference Scaglioni, Salvioni and Galimberti65). Mothers who are worried about their own weight tend to express concern about their daughter’s weight and impose more dietary restrictions(Reference Johannsen, Johannsen and Specker73). Parental recommendations should be in favour of preserving children’s self-control abilities, as well as modelling good habits(Reference Brown and Ogden74). This includes mealtime patterns, food and beverage choices, portion size, as well as favouring social interactions and avoiding digital interactions while eating(Reference van Nee, van Kleef and van Trijp75,Reference Tabares-Tabares, Moreno Aznar and Aguilera-Cervantes76) . Moreover, results of a recent qualitative study showed that parents are less aware of children’s self-control abilities for food intake and thus grant them little autonomy for determining their own food portion sizes(Reference Philippe, Issanchou and Roger77). Encouraging children to eat based on their natural sensations of hunger and fullness is crucial, and parents can help guide this process. However, it is important to avoid external pressures like rewards or large portion sizes. To establish healthy eating habits for their child, parents could be provided with alternative strategies like repeated exposure, hedonic contrast, enhancing pleasure and role modelling.

Tailoring nutritional recommendations and food-related activities to support parents

Due to their crucial role, parents are placed at the centre of actions and nutritional recommendations targeting childhood obesity(Reference Zivkovic, Warin and Davies78). In the first years of life, parents generally appreciate that the child’s development is monitored by health care professionals in child health centres(Reference Boelsma, Bektas and Wesdorp79). However, this appears to change as the child grows older, as a few studies, especially in the UK, have indicated. Parents of primary school-aged children expressed concerns about the child weight monitoring system in England, a surveillance programme aimed at identifying children who are above what is considered a healthy BMI, to make parents (and authorities) aware of this and offer support for weight management. In discussions posted online, parents argued that monitoring a child’s weight as part of the school programme can be stigmatising and not an accurate measure of overall health(Reference Kovacs, Gillison and Barnett80). This practice, in their view, may contribute to body shaming and negative self-image among children. Moreover, parents expressed feeling judged by health authorities and targeted as the ‘sole to blame’ for a child being overweight, a pattern also observed in other countries(Reference Fielding-Singh81,Reference Moura and Aschemann-Witzel82) . Mothers in particular expressed experiencing stress and anxiety induced by the difficulties in balancing nutrition recommendations from health authorities with several other family and life demands. Furthermore, in reaction to nutrition advice considered ‘authoritarian’ and ‘judgmental’, parents demonstrated an attitude change in the opposite direction of that advocated, a ‘boomerang’ effect, also referred to as ‘reactance’(Reference Moura and Aschemann-Witzel82).

Parents need support regarding how to behave in the feeding context and they often look for information via different sources (e.g. the internet, books, media)(Reference Chouraqui, Tavoularis and Emery83). The advancement of new technologies, including the wide utilisation of social media and forums, could lead to information overload(Reference Norton and Raciti84). Parents can experience that the available advice is inconsistent and even contradictory(Reference Moura and Aschemann-Witzel82,Reference De Rosso, Schwartz and Ducrot85) . It is paramount to guide parents to boost children’s healthy eating habits from an early age, which can be done by providing the best updated advice and guidance. As healthcare professionals are a widely used and trusted source of information for parents(Reference De Rosso, Nicklaus and Ducrot86), they could be placed as an additional target group for those public health strategies aimed at disseminating official recommendations. The current availability and nature of advice for different age groups of children is inconsistent, with more information available to parents on breastfeeding and weaning than feeding older children and adolescents. For example, Porter et al. (2020) reviewed portion size guidelines for children aged 1–5 years in the UK and identified significant variability in recommended serving sizes for dairy, protein and starchy foods among different organisations(Reference Porter, Kipping and Summerbell87). This inconsistency may create confusion and mistrust among parents seeking reliable guidance. Considering that mothers reported to already receive too much advice on feeding and parenting(Reference Moura and Aschemann-Witzel82), it is crucial that food and nutrition recommendations are succinct, clear, consistent and delivered in a non-judgmental manner.

Overall, nutrition counselling should respect the needs and wants of each family individually and avoid top-down advice that might be perceived as unattainable and threatening to individual freedom(Reference Fielding-Singh81,Reference Moura and Aschemann-Witzel82) . With regards to the family, the involvement of fathers is paramount, due to their pivotal influence on their family’s eating patterns(Reference Fielding-Singh81,Reference De-Jongh González, Tugault-Lafleur and O’Connor88) and because their involvement can decrease maternal stress from being solely responsible for the child’s health. Reaching out to and involving fathers can, however, be challenging in this field. In qualitative research, fathers expressed that they would prefer to participate in family-based interventions (not individual) and through online delivery due to time constraints(Reference Jansen, Harris and Daniels89). It is crucial to recognise and take into account the unique differences in parental feeding practices and styles, as well as the diverse roles played by individuals such as mothers, fathers, grandparents (who also have a significant impact, as shown by Jongenelis et al., 2021(Reference Jongenelis, Morley and Worrall90)) and other caregivers. For example, Philippe et al. (2021a) found that both mothers and fathers’ feeding practices significantly predict children’s eating behaviours(Reference Philippe, Chabanet and Issanchou91). Fathers reported using coercive practices more often than mothers, which can lead to unfavourable eating behaviours such as decreased enjoyment of food, increased pickiness and eating in the absence of hunger. Coercive feeding practices were also common among grandparents, who were reported to use rewards, encourage frequent eating and large portion sizes(Reference Marr, Reale and Breeze92). Interventions aiming at improving children’s healthy eating behaviours should thus consider the complexities of a child’s environment and family dynamics.

Thus, successful strategies to increase the intake of healthy foods in the family realm must respect individuals’ prior knowledge, core values and autonomy, and include all family members. As novel routes to this end, hands-on approaches to explore the sensory, commensal and gastronomic aspects of healthy foods, including food sensory play, picture book reading (with images and stories of new and/or disliked vegetables) and cooking sessions have shown promising results. The success of such practices stems from the fact (among others) that ludic activities, performed together as a family enhance feelings of ‘food joy’ (in parents’ own words); these strategies have shown to be particularly good for targeting fathers, as increasing fathers’ sense of self-efficacy towards cooking and tasting healthy foods has been shown as a motivator for the whole family(Reference Moura, Grønhøj and Aschemann-Witzel93). Positive emotions are indeed crucial to eating behaviour adoption, change and maintenance; practical playful activities can be even more effective as nutrition education. Shared food-related activities appropriately framed and guided as informative, but also ludic, have the potential to make healthy eating fun, enjoyable and therefore sustainable over time(Reference DeCosta, Møller and Frøst94).

The role of siblings in children’s healthy eating behaviour

From a systemic perspective, siblings belong to the same influence level as parents, as do school and community(Reference Bronfenbrenner, Morris, Lerner and Damon95). A systematic literature review(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj96) revealed that, although siblings are key actors in the family dynamics in which eating socialisation takes place, the nature and importance of siblings’ influence within the family dynamics is understudied. One of the rare studies on this topic examined the relative influence of siblings, peers and parents on adolescents’ diet quality(Reference Vanhelst, Béghin and Drumez97). Regarding siblings, the study found that brother’s and sister’s diet quality engagement (or perceived healthy eating, i.e. descriptive norms, cf. Cialdini et al., 1991(Reference Cialdini, Kallgren and Reno98)) is important for the quality of adolescents’ diets. The study also found that siblings’ encouragement was related to adolescents’ diet quality, balance and diversity components of the meal, although it concluded that among family members, mothers were most influential.

Comparing friends’ and siblings’ influence, Rageliené and Grønhøj (2021) concurred that sibling support for healthy eating and eating more frequently with siblings were associated with children’s consumption of vegetables, but age and number of siblings were not(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj99). This study also suggested that socialisation within the context of the family meal was the likely explanation for these findings, suggesting that the importance of siblings for children’s healthy eating may be a result of the positive interaction, communication and social modelling processes repeatedly taking place in the context of the family food environment. For instance, older siblings were found to provide their young siblings with encouragement for eating, which suggests a reflection of maternal behaviour(Reference Mosli, Miller and Kaciroti100). Thus, family meals are an important target for healthy eating interventions, considering the importance of family members, including siblings as a modelling influence for children’s healthy eating socialisation.

Using the power of social norms to promote healthy eating among peers and in school settings

Schools provide a widely used platform for reaching children and adolescents across socio-economic classes within many types of interventions. School meal programmes have a longstanding history and can be considered the most common type of intervention which can have strong short-term influences on children’s consumption of calories and key nutrients(Reference Oostindjer, Aschemann-Witzel and Wang101). In this context, eating becomes a social activity, where children learn by observing the behaviour of peers. Many other prevention programmes have also been conducted in schools with school-aged children and adolescents. These usually target a set of outcomes such as improving eating and exercise patterns by combining multiple intervention components. In this, there is an increasing plea for a ‘whole school’ approach that focusses on all aspects of children’s health and wellbeing.

Social norm theories have often been used as a theoretical point of departure for shaping children’s eating behaviour in a school setting(Reference Sharps and Robinson102), where many children spend much time and have lunch together with their peers. While ‘injunctive norms’ refer to what is perceived as ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ in a given culture, ‘descriptive norms’ refer to perceptions of how people commonly act(Reference Cialdini, Kallgren and Reno98). Previous studies have indicated that both injunctive and descriptive peer norms can have a significant influence on children’s food choices, taste preferences and eating behaviour(Reference Sharps and Robinson103–Reference Yun and Silk106). This is not surprising since the social influence of peers is believed to be important for framing children’s eating behaviour and food preferences(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Kelly107,Reference Smit, de Leeuw and Bevelander108) . Thus, although parents continue to be central(Reference Pedersen, Grønhøj and Thøgersen109), peers gradually increase in importance for children’s healthy eating socialisation(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj96,Reference Salvy, Roemmich and Bowker110) . However, Ragelienė and Grønhøj (2020b) found that the feeling of belonging and the need for peer approval predicted the actual intake of vegetables via injunctive but not descriptive norms of healthy eating(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj111). These findings suggest that interventions addressing aspects of children’s relationships with peers and injunctive norms for healthy eating might be helpful since peers’ social influence could improve healthy eating behaviour(Reference Cruwys, Platow and Rieger112).

Interventions implemented in a school setting should aim to help children build social communication to build their level of social self-efficacy and use the peer context to promote healthy eating behaviour to create new and ‘healthy’ social norms for eating(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj111). Successful school interventions that build on the idea of social communication and healthy role models include the Food Dudes programme in which children are exposed to heroic peers enjoying healthy eating, and subsequently being served healthy foods at lunchtime(Reference Horne, Tapper and Lowe113,Reference Wengreen, Madden and Aguilar114) . Schools can effectively promote healthy eating habits by not only providing nutritious food and beverages but also by setting eating rules and modelling positive eating behaviours by teachers and staff, thereby implicitly reinforcing the social norm of healthy eating.

The importance of the external food environments and the food supply chain

The external food environment, which refers to every opportunity to obtain food(Reference Townshend and Lake115), is currently characterised by the wide availability and affordability of energy dense and nutrient-poor industrialised products which contribute to unhealthy eating behaviours(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender12). During infancy and early childhood, the external food environment indirectly influences children’s eating behaviours through their caregivers, who are responsible for food purchasing. In addition, food marketing has a direct influence on children’s preferences, purchase requests and food choices(Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly116). The relevance of the external food environment increases when children become adolescents, as they develop cognitively and become more mobile, independent and increasingly responsible for making their own purchase decisions using their own money(Reference Schill, Godefroit-Winkel and Hogg117). Children’s autonomy gradually extends, which results in increased food decision making beyond the supervision of their parents or caregivers(Reference Reicks, Banna and Cluskey118). Considering that children and adolescents are particularly sensitive to reward(Reference Lowe, Morton and Reichelt119–Reference Nguyen, Girgis and Robinson121), their increasing independence may lead to more frequent consumption of unhealthy foods. In addition, adolescents are highly sensitive to social pressure(Reference Hargreaves, Mates and Menon122). Adolescents’ desire to feel accepted makes them more susceptible to social norms about healthy eating(Reference Lowe, Morton and Reichelt119,Reference Yeager, Lee, Dahl, Elliot, Dweck and Yeager123) , which may be exacerbated by food marketing. This is particularly relevant considering that adolescents are heavily targeted with unhealthy digital food marketing, e.g. through social media(Reference van der Bend, Jakstas and van Kleef124).

This section presents different aspects of children and adolescents’ external food environments, tapping into topics such as environmental strategies that could promote healthy choices, including nudging approaches and regulatory actions. Food supply chain-based approaches are also reviewed, with a focus on food production and the potential of food reformulation actions as well as listening to children’s voices in product development.

Changing food availability to nudge children and their families towards better dietary choices

External food environments define food availability (i.e. whether a food is available or not in a given context) and food accessibility (i.e. whether individuals can have physical, social and economic access to food)(Reference Turner, Aggarwal and Walls125). For example, in Singapore a survey of 9–16-year-olds and their parents found that having more fruits and vegetables at home led to increased intention to eat them, more enjoyment of eating them, and higher consumption of these foods(Reference Lwin, Malik and Lau126). Therefore, assuring availability of and access to healthy foods is a pre-requisite for achieving healthy eating habits in children and adolescents(Reference Larson and Story127).

In addition, both adults and children are often unconsciously influenced by the environment in their choices (such as the availability of healthy snacks at the checkout or the conspicuousness of products on a shelf) and use simple decision heuristics. Heuristics are mental shortcuts or simple ‘rules of thumb’ to unconsciously or automatically arrive at satisfactory solutions with minimal mental effort(Reference Shah and Oppenheimer128). While heuristics can help speed up decision making, they also lead to biases and errors in judgement(Reference Evans129). In the context of encouraging healthy eating habits in children, heuristics can play a key role in shaping their eating habits. To illustrate, children may use heuristics such as ‘I dislike green vegetables’ or ‘I prefer brightly coloured fruits and candy’ to guide their choices. To address these issues, nudging has emerged as a popular intervention technique that modifies the environment (commonly termed choice architecture) in which people select food to guide them to healthier choices, without relying on reasoning or restricting freedom of choice(Reference Thaler and Sunstein130).

By modifying the choice architecture, nudges strive to encourage the selection of healthier options by making them the socially acceptable, appealing or more convenient choice. For example, this can be accomplished by minimising the visibility of energy-rich snacks and drinks or enhancing the appeal of fruits and vegetables to align with children’s heuristics. One commonly mentioned example involves rearranging healthy products on supermarket shelves to be more easily accessible, typically at eye level. A comparable tactic was employed in a study conducted at middle schools in the USA, where relocated salad bars within the main serving line led to an increase in consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables during lunchtime compared with when salad bars were located outside the line after the point of purchase(Reference Adams, Bruening and Ohri-Vachaspati131). Also, children often react positively to ‘fun appeals’ specially created for them through packaging, cartoon images, shape, colour and language. Although mainly used for marketing unhealthy products(Reference Elliott132,Reference Elliott and Truman133) , these design aspects have also been used in nudge interventions to stimulate healthier choices. For example, presenting whole wheat bread in a fun shape (compared with a regular shape) almost doubled consumption during a breakfast event at primary schools(Reference Van Kleef, Vrijhof and Polet134). Sharps and colleagues (2020) employed pictorial nudges of grapes and carrots on tableware to boost primary school children’s intake of these nutritious foods(Reference Sharps, Thomas and Blissett135). The grape and carrot images likely increased their appeal and saliency, potentially indicating an appropriate portion size. Another study sought to nudge children in a restaurant towards healthier menu items by highlighting healthy options on the children’s menu with attractive descriptive names and the use of cartoon characters. However, contrary to expectations, the modified children’s menu did not lead to healthier orders compared with a neutral control menu(Reference Schneider, Markovinovic and Mata136). The authors suggest that parent–child social interactions are crucial in restaurant food-related decisions, as they often decide together, making the nature of their interaction significant. So, to effectively design interventions, it is crucial to take into account the influence of both the food environment and social interactions.

In general, meta-analyses and reviews of nudging studies show mixed results with small effect sizes, with the impact of nudging interventions dependent on the specific context, target behaviour, and population (e.g. Cadario & Chandon, 2020(Reference Cadario and Chandon137)), implying that further refinement and customisation of nudging strategies may be needed to better address the needs of children. Although the effect sizes of nudging interventions are typically small, they can still have a positive impact. Furthermore, nudging interventions are typically low-cost and easy to implement, making them a practical option for promoting healthy behaviours in various settings, including homes, schools and public spaces. For example, nudging tactics can also be applied by parents or caretakers at home. This could involve rearranging the placement of fruits and vegetables in the refrigerator or pantry for better visibility and accessibility, using attractive ways of serving the food, and positive reinforcement like praise or small non-food-based rewards to encourage healthier food choices.

Regulating the marketing of energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods

Food marketing is one of the key characteristics of modern food systems that shape social norms regarding what products are acceptable to be consumed in different life stages(14). It can be defined as: ‘any communication that is designed to increase the recognition, appeal, and/or consumption of particular food products, brands and services’(Reference Cairns, Angus and Hastings138). Food marketers spend significant budgets to target children and adolescents due to their direct and indirect purchasing power (i.e. through requests to caregivers)(Reference Folkvord, Anschütz and Boyland139,Reference Story and French140) . Research has shown that most food marketing targeted at children and adolescents, on both traditional and new digital media, promote energy-dense foods and beverages with a high content of sugar, fat and/or sodium(Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly116,Reference Cairns, Angus and Hastings138,Reference Freeman, Kelly and Baur141–Reference Kelly, Halford and Boyland143) .

Exposure to marketing raises awareness about the existence of specific brands and products, increases product recall and recognition, creates positive attitudes and preference towards the promoted products, and ultimately encourages purchase and consumption of such products(Reference Kelly, King and Chapman144). Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to food marketing given that their choices are largely determined by immediate gratification(Reference Marty, Miguet and Bournez120). Furthermore, children under the age of 8 years do not have the cognitive ability to identify the persuasive nature of marketing(Reference John60,Reference Lapierre, Fleming-Milici and Rozendaal145) . The new use of social media through children and adolescent influencers adds to this complexity, with further effects on shaping product preferences or increasing ‘pester power’. By increasing levels of trust, because these influencers are also ‘everyday people’, social media leads to a more ambiguous separation of what is or is not marketing for both children and caregivers. This can even make parents believe consuming unhealthy products is more socially acceptable, being promoted by videos with millions of views. Increasingly worrisome is that this specific type of marketing is largely understudied and underregulated(Reference Alruwaily, Mangold and Greene146).

A large body of evidence shows a negative association between exposure to marketing of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods and beverages, and diet quality in both children and adolescents(Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly116,Reference Cairns, Angus and Hastings138,Reference Buchanan, Kelly and Yeatman147–Reference Smith, Kelly and Yeatman149) . For this reason, the implementation of policies to reduce the impact of marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children and adolescents has been identified as one of the priorities for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases by the WHO (2013)(150). However, worldwide the progress has been slow and only a handful of countries have implemented mandatory regulations to restrict marketing of unhealthy foods to children and adolescents(Reference Taillie, Busey and Stoltze151). Research has shown that such policies can be effective at reducing the exposure to and power of marketing, which may lead to a reduction in the purchases of unhealthy foods(Reference Correa, Reyes and Taillie152–Reference Lwin, Yee and Lau157). To date, Chile has the most comprehensive policy to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents(Reference Taillie, Busey and Stoltze151). The policy restricts marketing of foods and beverages with added sugar, sodium and/or saturated fat that exceed nutrient thresholds for calories, total sugars, saturated fat and sodium (‘high in’ products) to children and adolescents younger than 14 years old(158). It includes television, radio, cinema, digital marketing, print, outdoor media, packaging, point-of-sale, sponsorships, marketing in school settings and marketing at public settings (e.g. events). The policy bans the use of cartoon characters and mascots that appeal to children, as well as movie tie-ins, child figures, games, contests, references to children, toys, stickers and other accessories in marketing of ‘high in’ products across all media and packaging(Reference Taillie, Busey and Stoltze151). Marketing of ‘high in’ products in TV and cinema is only allowed between 22:00 and 06:00, only if they are not targeted at children under 14 years old(158). The consequences of these marketing restrictions on children’s health are still being studied, but the results are expected to improve children’s dietary intake.

Improving food labelling

Packaging has become an inexorable part of the modern food environment and a key component of the marketing strategies of food companies(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159). Food packages are a source of information which contribute to overcoming the information asymmetry between producers and consumers(Reference Fung, Weil and Graham160). Food companies include information about product identity, quantity and freshness, but also a wide range of visual and textual cues to attract consumers’ attention, shape product associations and influence purchase decisions(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159,Reference Spence161) . Research has shown that packages have an important effect on children’s diets by influencing both the parents’ choice of food for their children and the foods children actively choose or request(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159).

Food packaging is the most important strategy marketers use to target products at children, through the inclusion of cartoon characters and other ‘fun’ visual and textual references on food labels(Reference Elliott132,Reference Elliott and Truman133) . These cues have been widely reported to attract children’s attention and trigger requests of energy dense, nutrient-poor foods at the point of purchase(Reference Ogle, Graham and Lucas-Thompson162–Reference Ford, Eadie and Adams164). For this reason, banning packaging elements that attract children’s attention for products with high levels of sugar, salt and fat, associated with non-communicable diseases, has been regarded as a top priority in policy making(Reference Elliott and Truman133,Reference Hawkes165) . So far, only two countries worldwide, Chile and Mexico, have introduced packaging regulations to ban the use of marketing strategies aimed at attracting children’s attention on products high in energy density, sodium, saturated fat and sugar(Reference Taillie, Busey and Stoltze151).

Furthermore, packages frequently include a wide range of health-related cues, such as regulated nutrition claims, nutrition marketing claims and design features (e.g. colour, pictures),(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159,Reference Christoforou, Dachner and Mendelson166,Reference Van Buul and Brouns167) . Such cues elicit health-related associations among children and parents, encouraging them to choose products with cues over those without them(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159,Reference Lähteenmäki168) . According to Slaughter and Ting (2010), school-aged children have a positive attitude towards products with nutrient claims, even if they are not necessarily aware of the health benefits of the specific nutrients(Reference Slaughter and Ting169). This effect has been associated to the frequent inclusion of these claims on food packages and marketing campaigns. Therefore, regulations are necessary to ban the inclusion of health-related cues on the packages of food products with an unfavourable nutritional composition(Reference Ares, Velázquez and Vidal159,170) . In this sense, new labelling regulations are currently being discussed in the USA to increase transparency and protect consumers from misleading claims(171).

Packages can also be used as a tool to facilitate the identification of foods that contribute to a healthy diet(Reference Scarborough, Rayner and Stockley172). In this sense, the inclusion of simple and graphical nutritional labels on the front-of-packages (FOP) is gaining increasing attention among policymakers worldwide to provide summarised information about the nutritional composition of products(Reference Jones, Neal and Reeve173). Although a wide range of schemes has been developed worldwide(174), research has shown that those including interpretive aids are the most efficient in enabling consumers to correctly judge the healthfulness of products and differentiate healthy from less healthy products(Reference An, Shi and Shen175,Reference Temple176) . These interpretive FOP nutrition labelling schemes include logos highlighting healthy products, warnings highlighting products with high content of nutrients associated with non-communicable diseases, and schemes providing an overall score of product healthfulness based on both positive and negative nutrients(Reference Jones, Neal and Reeve173,174) . Although a large body of research has compared the efficacy of interpretive FOP nutrition labelling schemes, results are inconclusive regarding which is the best scheme to encourage healthier food choices(Reference An, Shi and Shen175,Reference Temple176) . However, several studies have shown that schemes highlighting unhealthy foods, such as the NutriScore and warning labels, are more efficient than logos highlighting only healthy foods (e.g. de Alcantara et al., 2020(Reference De Alcantara, Ares and de Castro177); Ducrot et al., 2016(Reference Ducrot, Julia and Méjean178); Talati et al., 2016(Reference Talati, Pettigrew and Dixon179)).

So far, only a limited number of countries worldwide have implemented FOP nutrition labelling regulations and most of them remain voluntary(Reference Jones, Neal and Reeve173). Voluntary regulations have resulted in poor uptake by the food industry, which implies that consumers do have simplified nutritional information for most of the products available in the marketplace(Reference Kelly and Jewell180). For this reason, mandatory FOP nutrition labelling regulations are needed to ensure consistent uptake and to enable consumers to make informed decisions. Incidentally, most of the countries which have mandatory regulations, have implemented nutritional warning labels(Reference Jones, Neal and Reeve173,174) . This FOP nutrition labelling scheme has been shown to be effective at improving consumer ability to identify products with high content of nutrients associated with non-communicable diseases and discouraging the selection of products high in sugar, fat and/or sodium(Reference Ares, Antúnez and Curutchet181–Reference Ares, Antúnez and Curutchet185). This scheme has been reported to reduce children’s positive emotional associations with food labels and to discourage them from choosing unhealthy products(Reference Lima, de Alcantara and Martins186,Reference Arrúa, Curutchet and Rey187) .

Food reformulation actions

Modern food environments are characterised by the wide availability of products with high energy density and high content of sugar, fat and sodium(188). This is the case for most products targeted at children(Reference Elliott and Truman133), which usually contain higher sugar content than those targeted at the general population(Reference Rito, Dinis and Rascôa189,Reference Moore, Sutton and Hancock190) . Thus, food reformulation has been identified as one of the most cost-effective policies to create supportive food environments that encourage healthier diets(Reference Dobbs, Sawers and Thompon191). Food reformulation aims at improving the nutritional composition of products, mainly by reducing the content of nutrients associated with non-communicable diseases, i.e. free sugars, sodium, total fat, saturated fat and trans-fat(Reference Waxman192). Sometimes, substitutes or flavour enhancers (e.g. spices) can be used to create products that children and adolescents like. Reformulation can increase the availability of healthy products in the marketplace, which may lead to an improvement in the quality of the diet at the population level even if consumers do not change their purchase decisions(Reference Federici, Detzel and Petracca193–Reference Yeung, Gohil and Rangan197). To generate meaningful changes in children and adolescents’ nutrient intake, food reformulation programmes should be applied across most of the product categories available in the marketplace.

A wide range of reformulation programmes have been implemented worldwide, ranging from voluntary industry commitments to mandatory governmental regulations(1,Reference Scott, Hawkins and Knai198) . Mandatory reformulation programmes have been reported to have several advantages over voluntary initiatives, as they are applicable to all manufacturers and typically have a larger impact on the nutritional composition of the foods available and the marketplace(Reference Vandevijvere and Vanderlee199). Alternatively, governments can implement responsive regulatory approaches, which typically start with voluntary reformulation programmes that progress to mandatory if the industry fails to achieve the targets(Reference Reeve and Magnusson200). A successful example of this approach is the salt reduction programme implemented by the UK in 2003(Reference He, Brinsden and Macgregor201). In addition, the implementation of other policies, such as FOP nutrition labelling or taxes, can encourage the food industry to reformulate their products. This effect has been reported after the implementation of warning labels(Reference Reyes, Smith Taillie and Popkin202) and in the UK after the implementation of a sugar tax(Reference Forde, Penney and White203).

One of the main challenges for the implementation of these actions is the belief that consumers would not accept the reformulated products(Reference Deliza, Lima and Ares204,205) . To avoid such problems, gradual reformulations have been recommended so that consumers do not perceive any change(Reference MacGregor and Hashem206). Once consumers are adapted to the sensory characteristics of the reformulated product, a new change in product composition is implemented(Reference Zandstra, Lion and Newson207). Although gradual salt reduction has been successfully implemented, progressive sugar reduction programmes have not been widely extended worldwide(Reference Hashem, He and Macgregor194,Reference Vandevijvere and Vanderlee199) . This may be explained by the fact that while preference for saltiness depends on the intensity level to which we are exposed and may be relatively easily changed with exposure(Reference Methven, Langreney and Prescott208,Reference Beauchamp, Stein, Masland, Albright and Dallos209) , this is not the case of sweetness. For sweetness, the evidence of the impact of varying exposure on subsequent generalised sweet taste preferences is equivocal regarding the presence and possible direction of a relation(Reference Appleton, Tuorila and Bertenshaw210). However, it is worth stressing that experimental research has shown that significant sugar reduction can be achieved without affecting children’s hedonic perception, even if products are perceived as less sweet(Reference Deliza, Lima and Ares204,Reference Velázquez, Vidal and Varela211) .

The main advantage of gradual reformulation programmes is that consumers develop preferences for products with lower sweetness, saltiness and/or fattiness through repeated exposure(Reference Rozin25). This is particularly relevant for children, as early experiences with food have a key role in food preferences and choice later in life(Reference De Cosmi, Scaglioni and Agostoni212). Finally, it is worth mentioning that both children and adults individually differ in their responsiveness to basic tastes, and this contributes to their food preferences(Reference Joseph, Reed and Mennella213). Reduction of levels of sugar/salt should consider this individual diversity: for some (more taste responsive) children it could be easier to like foods that are less sweet/salty, while for others, this might be more difficult(Reference Ervina, Almli and Berget37,Reference Tepper214) . This may open the path towards more diversity in terms of reformulated products available in the marketplace, with the possibility of integrating different strategies to make them more effective especially with more responsive children (that tend to dislike less sweet/salt foods). This would allow to improve the acceptability of reformulated products. However, how to communicate these diverse product sensory experiences is still an open challenge.

Co-creation of healthy foods and meals with children

Researchers stress the need to further include children’s perspectives in strategies to promote their healthy eating, assuring that their needs and aspirations are met(Reference Neufeld, Andrade and Ballonoff Suleiman20,Reference Hargreaves, Mates and Menon122) . Furthermore, a wider involvement of children responds to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989): ‘Every child has the right to express their views, feelings and wishes in all matters affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously’(215). Children’s ideas and perspectives could not only inform the transition to healthier food systems by including their views and ideas in product reformulation; the reflection about healthy eating and the creative solutions that participating children develop during the process might be just as important in shaping a generation with agency and capacity to make their own choices regarding their health and well-being. However, children’s involvement is still scarce as they are perceived as less competent to provide valid insights and solutions due to, for example, cognitive and language barriers. Children’s ideas would not necessarily always be related to healthy food, but they can give product developers indication of what aspects of foods they give more importance to and enjoy(Reference Galler and Varela216). Also, the ethical perspective of using children in co-creation can be challenging, instigating questions about the ownership of the idea, particularly for commercial applications, or if the benefit of being heard outweigh the right to protection(Reference Galler, Myhrer and Ares217).

Recent studies aimed to change this deficit-based perspective by involving children and adolescents as co-creators of food policy strategies(Reference Savona, Macauley and Aguiar218,Reference Ares, Antúnez and Alcaire219) and product innovation(Reference Galler, Gonera and Varela220–Reference Waddingham, Shaw and Van Dam222), acknowledging their capacity for creativity and their right to shape their own future food systems. The latter authors have suggested a variety of participatory methods suitable for children to co-create healthy food. In the initial stages of product development, creative and enabling methods were proposed to explore what motivates children’s food choices and to develop healthier food ideas(Reference Galler, Myhrer and Ares217,Reference Waddingham, Shaw and Van Dam222) . For later stages of the development process, prototyping and sensory testing were used in an interactive, iterative way, to formulate and optimise products adapting them to children’s preferences(Reference Velázquez, Galler and Vidal221). Co-creation can be extended to other stages of the development process of new products or meals, drawing onto the concept of design-thinking, for instance working in direct collaboration with chefs(Reference Olsen223). This could also be used as an intervention in itself, with children reflecting on healthy eating, enlarging their food repertoire and developing agency and self-efficacy(Reference Galler, Myhrer and Ares217,Reference Olsen224) . Also, meaning can be co-created(Reference Ind and Coates225); that is to say, the co-creation of what healthy and pleasurable eating means for children could be an important aspect in the promotion of healthy food and social marketing. Today, creating and sharing food content is a part of young people’s online activity shaping their social norms about eating through peer influence(Reference Chung, Vieira and Donley226). Therefore, digital media is an interesting setting to generate solutions that align with peer norms. While the harvesting of user content of existing digital media platforms may pose concerns regarding data protection rules, ‘social media-like’ online platforms can be established for the purpose of co-creation initiatives where the access is limited to the involved consenting group (Galler et al., 2022).

Modifying economic access to foods

Access to food that is safe and adequate for an active and healthy life is a basic human right(227). However, major drivers of food insecurity (e.g. wars, economic instability and climate change) have intensified in recent years, leading to an increase in the percentage of people affected by hunger(228). This stresses the importance of implementing policies to secure economic access to food, including immediate hunger relief programs, such as cash transfers and food provision(Reference O’Hara and Toussaint229). In addition, innovative and transformative policies are needed to address the structural causes of food insecurity: such as low wages, adverse social and economic conditions, racial segregation, and conflict(228,Reference Drewnowski230) .

Food prices and particularly the relationship between the price of healthy and unhealthy foods have been identified as key determinants of food choices, especially among people from low socio-economic status(Reference Lee, Mhurchu and Sacks231) (Lee et al., 2013). For this reason, policies aimed at introducing changes in food prices have gained attention as part of the comprehensive set of strategies that should be implemented to promote healthy diets(Reference Afshin, Peñalvo and Del Gobbo232).

Subsidies to healthy foods targeted at the most vulnerable sectors of the population have been shown to be effective at promoting the purchase of healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables(Reference Afshin, Peñalvo and Del Gobbo232,Reference Andreyeva, Marple and Moore233) . A decrease of 10% in the price of healthy foods has been associated with a 12% increase in consumption(Reference Afshin, Peñalvo and Del Gobbo232). Different alternatives for the implementation of specific subsidies on healthy foods have been implemented, including discounts on purchases at the point of sale, delivery of coupons or vouchers, and refunds of money after purchase(Reference An234).

Taxes have been proposed to increase the price of unhealthy foods and discourage their consumption(Reference Lee, Mhurchu and Sacks231). Sugar-sweetened beverages are the main category where this type of policy has been implemented worldwide. In 2020, more than 45 countries and jurisdictions had health-related taxes in place to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and improve population health outcomes(Reference Andreyeva, Marple and Moore233). The most recent evidence suggests that taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages are successfully associated with higher prices and a reduction in sales(Reference Andreyeva, Marple and Moore233).

Public health guidelines and social marketing to promote healthy eating

Public health organisations have formulated guidelines to offer a global vision of children’s healthy eating based on scientific insights. Nutritional guidelines are released by health authorities and differ between countries; however, they are normally disseminated to the population in the form of recommendations (nested in health messages) by various means of communication: nutrition guides, official websites and campaigns on traditional and social media. One of the problems in developing a public health communication campaign is to respond to the needs of the majority of the target population (e.g. parents or children and adolescents). Some principles of social marketing are applied when programming public health communication strategies focussing on behavioural change(Reference Dresler-Hawke and Veer235). This approach includes, for example, the prefixing of public health as well as communication objectives and an audience analysis. The aim is to identify segments for specific procedures, to design targeted and effective messages and efficient strategies to deliver those, leading to successful reception by the public(Reference Ling, Franklin and Lindsteadt236).

Public health communication actions could have unintended adverse effects, indirectly contributing to expand knowledge and social gaps within the target population(Reference Guttman and Salmon237). When communicating about health, an inclusive approach should be used to reduce health disparities. At present, there are no boundaries between evidence-based information and non-validated information(Reference Paganelli238), paving the way for ‘fake news’ in all domains, including nutrition. The use of the internet and other technologies facilitates access to information, but also makes it difficult to distinguish whether this can be trusted or not. Reaching health equity by keeping high effectiveness of campaigns or prevention interventions is a public health dilemma(Reference Williams, Walker and Egede239,Reference Daniels240) ; this implies providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit, with the aim of minimising disparities(Reference Mayberry, Nicewander and Qin241).