LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• recognise the importance of a clinical review at 24 h if a section 136 expires while awaiting an in-patient bed

• recognise the limitations of all current forms of legislation considered to manage this dilemma

• communicate the ethical and legal complexity of this situation effectively and appropriately to staff and patients.

Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 enables police officers in England and Wales to transfer a person who appears to have a mental disorder and to be in ‘immediate need of care or control’ to a place of safety (PoS) (Department of Health 2015). Often this will be based within a mental health unit or accident and emergency (A&E) department, but police stations are also sometimes used, depending on the situation.

Detention under section 136 was originally valid for 72 h. However, changes in legislation in December 2017 resulted in the validity period being reduced from 72 h to 24 h (Home Office 2017). The period can be extended by 12 h, but only on clinical grounds. An example of such a situation would be if there is a delay in being able to complete the initial assessment owing to an individual's level of intoxication.

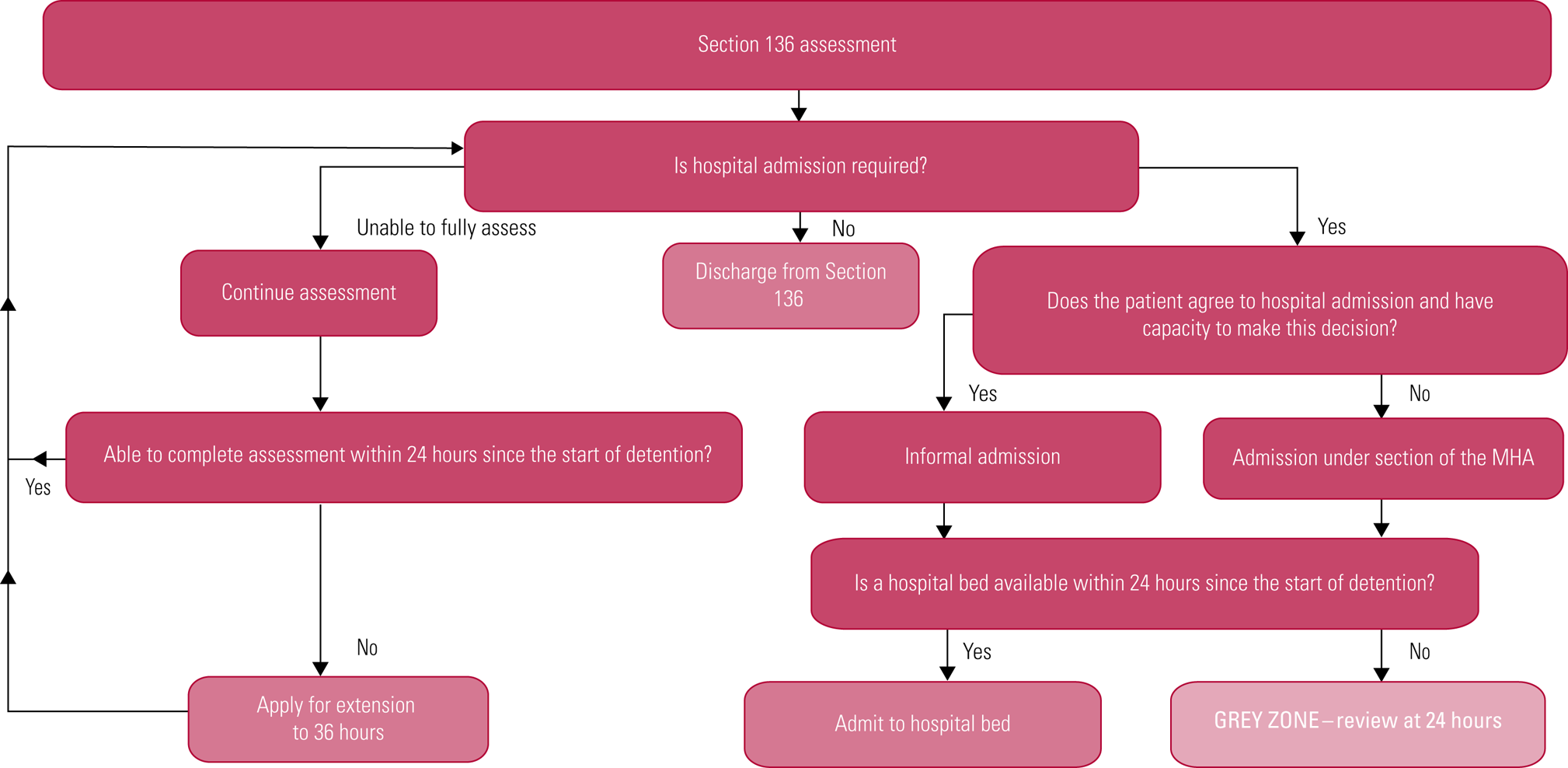

With a combination of reduced in-patient bed availability (Ewbank Reference Ewbank, Thompson and McKenna2017) and rising section 136 referrals (Loughran Reference Loughran2018), the reality is that there are also non-clinical reasons why the 24-h validity period may expire. The main example of this is that individuals are being held in the PoS after the end of the validity period, while waiting for an in-patient psychiatric bed to become available. When this occurs, they can no longer be lawfully detained under section 136, but there is no clear consensus as to the procedure that should follow. For this reason, we have referred to this period as the ‘grey zone’. Figure 1 depicts the usual outcomes of section 136 referrals, as well as the pathway for the subset of individuals who fall into the grey zone. This article will describe some of the varied practices used currently by National Health Service (NHS) trusts to manage this situation, each practice bearing its own legal vulnerabilities.

FIG 1 Section 136 pathway into the ‘grey zone’.

Reviewing the need for continued detention

Usually trusts do and should ensure that a clinician reviews a patient at the point of the section 136 expiring. If a section 136 is expiring because a bed is not available, the purpose of this review will include determining whether an admission remains the least restrictive option in managing the current illness and risks. Depending on the trust, this responsibility may be allocated to various grades of doctor – core trainees, registrars or consultants. It is possible that the clinical situation changes during the grey zone, and a hospital admission may no longer be the least restrictive option. However, the confidence to overturn a decision to admit the patient, and instead to consider discharge from hospital, may well rest on the expertise of the assessing doctor in the application of the Mental Health Act. In effect, this can mean that some patients will continue to be held in the PoS following expiry of the section 136 validity period to await a bed that they no longer require.

Duty of candour

Continuing to hold a patient in the PoS following the expiry of their section 136 because of non-clinical events is both unlawful and can prolong psychological harm. For example, in the case of an individual who is awaiting transfer to an open in-patient ward, continuing to use the confined space of the PoS would be more restrictive than is necessary. There is a risk that this may in fact exacerbate the presenting mental illness.

As a result, and in line with the polices of many trusts, we argue that duty of candour should apply (General Medical Council 2015). Patients should be informed of the reasons that they are remaining in the PoS, the legal grounds being used, the level of restrictions imposed on them and the frequency at which these restrictions will be reviewed.

Legal grounds to continue use of the PoS following section 136 expiry

There is a lack of uniformity among trusts in relation to what, if any, legal grounding may be considered to continue use of the PoS in the grey zone.

Some trusts advocate the use of common law in situations where continued use of the PoS is deemed necessary. The common law of necessity enables the use of reasonable, necessary and proportionate steps to protect a citizen from hurting themselves or others (R (Munjaz) v Mersey Care NHS Trust 2003). Its applicability may be more evident in situations where physical restraint is required to ensure the immediate safety of a person. However, in cases where the risks are not so clear and immediate, common law would not be sufficient to justify continued use of the PoS.

A mental capacity assessment for consent to treatment has also been used for this purpose, and it may be a better tool for justifying management of more complex risks. If the patient is deemed to have capacity, then the assessment may enable them to voluntarily agree to remain in the PoS while awaiting an in-patient bed.

If the patient lacks capacity, however, and the level of restrictions being imposed on them involve constant supervision and control, where they are not free to leave (as is the case with the PoS), then it would follow that they would qualify for protection under the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) within Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Department of Health 2008). Nonetheless, some would argue whether the Mental Capacity Act is ever adequate in these situations, where in effect it is being used as a holding power when the Mental Health Act would otherwise deem this to be unlawful. As an extension of this, it could be reasoned that an application for DoLS would legitimise the use of an already questionable practice of justifying continued use of the PoS using the Mental Capacity Act in the grey zone.

Recommendations

We conclude that reduction of the section 136 validity period to 24 h, while well-intentioned, has inevitably created a ‘grey zone’ with inconsistent practices for managing situations when the assessment process has been completed within 24 h but no in-patient bed is available.

We propose that all individuals should be reviewed by a section 12 (approved) doctor at the time that the section 136 lapses, to determine the need for continued use of the PoS in their management. If the person must remain in the PoS, duty of candour will apply. They and their family should be informed of the reasons for the continued use of the PoS, the legal grounds being used, the level of restrictions imposed on them and the frequency at which these restrictions will be reviewed.

The current options, including the use of common law and the Mental Capacity Act, are inadequate in justifying continued use of the PoS beyond the validity of the Mental Health Act's section 136. Moreover, one must consider that, if justifying the use of the Mental Capacity Act, then the DOLS framework would also apply.

In line with the Mental Health Act Code of Practice (Department of Health 2015), there must be local recording and reporting mechanisms in place to note the details of all delays caused by lack of in-patient bed availability, as well as the wider impact of such delays on patients and staff. This information should then feed into local policy, so that provisions can be made following liaison with local authorities, and NHS commissioners and providers. It may be possible, for example, that an intermediary place is agreed on for use following expiry of the section 136, with the intention of this being less restrictive and more acceptable to patients than the current PoS, while awaiting an in-patient bed.

In the long-term, we argue for a clear nationally developed legal framework to advise on how to manage the grey zone, which should be contained ideally within the Mental Health Act, and with the intention of continuing to promote the guiding principles of the Code of Practice. This will both support consistent practices between trusts and safeguard the rights of patients in these circumstances. Ultimately, the outcome of this dilemma may well be decided through case law.

Author contributions

Y.R. and M.K. were involved in the conception, analysis and drafting of this article.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.22.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 A section 136 is valid for:

a 12 h

b 24 h

c 36 h

d 48 h

e 72 h.

2 The validity period may be extended by:

a 3 h

b 6 h

c 9 h

d 12 h

e 18 h.

3 A section 136 can legally be extended if the patient is:

a physically aggressive during assessment

b refusing to speak during assessment

c too intoxicated and assessment has been delayed

d transferred to another place of safety

e assessed as needing admission but no in-patient bed is available.

4 Deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) are a part of the:

a Mental Capacity Act 2005

b Mental Health Act 1983

c common law of necessity

d Mental Health (Discrimination) Act 2013

e Equality Act 2010.

5 Duty of candour applies when an incident has:

a caused death

b caused physical harm

c caused psychological harm

d prolonged psychological harm

e all of the above.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 d 3 c 4 a 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.