12.1 Introduction

There is a growing awareness amongst academics, government officials, and experts from international and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that economic policies impact men and women differently. The difference is probably the result of social systems where different kinds of inequalities exist. In these systems, social relational contexts are fundamental as they shape a gender regime which conditions sex segregation in jobs, division of labour, and gender differences in social positions in authority, among others.Footnote 1 Therefore, it has been recognized that mainstreaming gender perspectives into policymaking is crucial to ensure women’s economic autonomy and has a positive effect on development.Footnote 2 In this context, gender issues have been included in international trade policy agendas, acknowledging that countries with higher levels of political and economic participation by women are closer to achieving gender equality as well as a higher level of global competitiveness.Footnote 3

New preferential trade agreements (PTAs) include gender considerations because: more women are part of policymaking than before; an increasing number of women own or manage export firms and trade in international markets; advocacy campaigns are raising awareness of the relevance of gender equality issues; research is being conducted on the gender dimension of trade policy; and there is a widespread belief that trade can be instrumental for long-lasting development only if it is more inclusive and its benefits are more equally shared.Footnote 4

South American countries have adopted a proactive attitude towards the inclusion of a gender perspective within their trade policymaking. For example, at the regional level, the Pacific Alliance can be highlighted due to the implementation of a roadmap to address women’s economic autonomy and empowermentFootnote 5 and, at the bilateral level, the Chile–Uruguay FTA became the first to include a gender and trade chapter.Footnote 6 This chapter became a template for trade negotiations worldwide, as well as a stepping stone for the evolution of such chapters in other agreements.

The main objective of this chapter is to analyse how South American economies have mainstreamed gender issues in their trade agreements, and to identify common elements in such agreements and their evolution. For this purpose, the chapter reviews the incorporation of gender provisions in bilateral trade agreements and the region’s integration processes (Pacific Alliance and Mercosur). With respect to the methodology used, this chapter analyses and compares primary and secondary sources, and, in particular, presidential declarations from integration processes and the contents of the text of various FTAs, their enforcement and governance. Moreover, in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders from the public sector were conducted to complement previous analysis, looking into the motivations and reasons behind the different legal clauses.Footnote 7 The results of the interviews are woven into the text of the chapter, which also includes analysis in specific sections. The field research – which includes face-to-face and virtual interviews prior to the pandemic, and online zoom interviews after lockdown and during social distancing measures – was conducted between December 2018 and October 2021 and entailed interviews with stakeholders from Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico, as well as representatives from international organizations. In total, thirty-four interviews were carried out with a variety of stakeholders, including former trade ministers, vice ministers, negotiators, experts from international organizations, and academics. Due to the positions interviewees hold, the results have been anonymized. Moreover, although there is consensus regarding the incorporation of gender provisions in international trade agreements, a divergence in opinions is found between members who hold public office and members from international organizations and academia. This chapter demonstrates how South American countries have advanced their trade policymaking regarding gender-sensible regulations, which has been influential for trade and gender negotiations in other regions.

This chapter is divided into the following sections. Section 12.2 reviews the relevant literature regarding the inclusion of gender issues in trade policy. Section 12.3 revises gender mainstreaming in the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur. Then, Section 12.4 presents an overview of gender inclusion in South American PTAs. Section 12.5 presents analysis of the inclusion of gender provisions in South America’s FTAs. To conclude, Section 12.6 contains final remarks and policy recommendations.

12.2 Gender Mainstreaming in Trade Policy Instruments

It is crucial to analyse FTAs through a gender perspective. This would contribute to determining whether the decisions of a society favour the search for social and economic justice and the scope and limitations of macroeconomic policies. The literature has established that trade strategies which are focused on lowering labour costs and maintaining gender disparities can cement a path of underdevelopment and obstruct the transition to sustainable development.Footnote 8 Through the incorporation of a gender perspective into FTAs, governments can push their trade partners to develop laws and processes that decrease obstacles to women’s access to trade.Footnote 9

The first multilateral step towards including gender in international trade policy goes back to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) claim that trade liberalization is linked to greater accumulation of education, skills, and increased gender equality.Footnote 10 This claim has led international organizations and governments to incorporate a gender-based perspective within their trade agenda, making it a worldwide priority.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, there is no consensus to include gender within multilateral negotiations amongst WTO members. Many WTO members have argued that the WTO should deal only with trade-related issues that imply trade distortions, but not social issues such as gender inequality.Footnote 12 Some NGOs have argued the opposite, as gender equality contributes to economic growth and poverty reduction, and women make up 70 per cent of the world’s poorest share of the population.Footnote 13 Although it was not included in the trade negotiation agenda, the 2017 Buenos Aires Declaration on Women and Trade,Footnote 14 which aims to promote and remove impediments to women’s economic empowerment, was endorsed by 118 WTO members and observers.Footnote 15 Moreover, in the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference, held in Geneva in June 2022, members recognized the relevance of women’s economic empowerment and the work that international organizations such as the WTO, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and the International Trade Centre (ITC) are doing in this respect.Footnote 16

Gender considerations must be a part of the integral design of the different trade policies.Footnote 17 The literature has identified the following trade policy tools that could contribute to gender equality:

First, gathering specific trade and gender information can mitigate the lack of data about women in economic roles.Footnote 18 Since December 2017, following the Buenos Aires Declaration, countries have sought to exchange methodologies and processes for collecting gender-disaggregated data and analysing gender-focused trade statistics.Footnote 19

Second, the participation of civil society and private stakeholders, including business chambers and women’s organizations, can be instrumental in identifying gender objectives within trade policy and advocating for this change in the future.

Third, ex ante and ex post evaluation of the impact of an agreement on women, and the necessary adaptation and compensation for the impact of trade on women, are important to produce evidence on how trade impacts gender concerns.Footnote 20 Trade policies that will favour women’s well-being and empowerment and mitigate gender disparities can use an ex ante assessment to analyse the potential impacts on specific segments of the population.Footnote 21

Fourth, the increasing participation of women in the policymaking process, international markets, and the awareness brought by different campaigns for gender equality in the last few years have allowed the incorporation of gender chapters in trade agreements.Footnote 22

Fifth, mainstreaming gender in all trade disciplines can be achieved through the prohibition of gender discrimination, the inclusion of affirmative actions, and reservations in areas where the state’s regulatory power over gender equality must be protected.

Sixth, the implementation of trade facilitation measures including borders and customs, commerce and transportation infrastructure, and logistics which may benefit women by ensuring a more predictable and inclusive workplace.Footnote 23

Seventh, the promotion of women’s export entrepreneurship, and the elimination of restrictions and legal barriers to access financing can also help in addressing gender concerns within the trade policy context. The inclusion of women entrepreneurs and workers in higher-level sectors such as knowledge-intensive activities may promote a more gender-equal society. This can be reinforced by enhancing women’s participation in leadership positions within productive structures, including regional and global value chains. Moreover, the latest developments due to the COVID-19 pandemic have raised the awareness of the care economy and women’s participation in the digital economy.Footnote 24 Against that background, the following section provides a discussion on how the existing trade agreements in South America have embraced these gender-mainstreaming tools.

12.3 Gender Mainstreaming in South America’s Main Integration Processes

The most important processes of economic integration in South America include Mercosur and the Pacific Alliance. Mercosur was established in 1991 by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, with the objective of creating a deep integration process in the region to foster economic and investment opportunities. The Pacific Alliance is a more recent initiative established in 2011 by Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru to promote members’ higher economic growth and competitiveness through a mechanism of economic, political, and social articulation.

12.3.1 Gender-Specific Policies under Mercosur

The incorporation of women and gender has been a longstanding topic of discussion in Mercosur’s working agenda. Members have incorporated different actions in their integration process work, including the Specialized Meeting of Women, a body that was created in 1997. This body was established in response to the increasing demand of civil society and women’s movements for a forum to foster the analysis of women’s situations and contribute to the social, economic, and cultural development of various communities. Amongst other issues, the meeting recommended male–female parity in the composition of the Mercosur Parliament.Footnote 25 Moreover, in 2008, a project to strengthen gender institutions and policies was implemented in cooperation with the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation.

Mercosur members have also worked towards the collection of gender-disaggregated data, for which a diagnosis on indicators on domestic violence was released in 2010. In 2011, on the occasion of the 100th Summit of the International Labour Organization (ILO), a Joint Statement was issued to support ILO Convention 189 on decent work for domestic workers. In the same year, the gender perspective was incorporated into the Strategic Social Action Plan, following which the Women’s Ministers and High Official Meeting of Mercosur (RMAAM) was established. This led to the Mercosur Gender Equity Policy, built in collaboration with various regional forums and women’s organizations.

Another important topic analysed by Mercosur members relates to trafficking of women, and in particular the identification of domestic and international routes used for such trafficking. This led to the establishment of a Mercosur Guide on awareness of women victims of trafficking with the purpose of sexual exploitation.Footnote 26 In 2014, the Mercosur Guidelines on Gender Policy were approved, setting the ground for equality and non-discrimination of women in the region from a feminist and human rights perspective.

As stated, while Mercosur has acknowledged the relevance of incorporating a gender perspective in its social and governance agenda, it has not yet addressed this topic in relation to trade or trade agreements. In this context, Mercosur’s trade liberalization has been argued to have mixed and potentially detrimental effects.Footnote 27 Further, analyses show that current Mercosur international trade patterns tend to benefit male-oriented sectors, and do not contribute to women’s employment.Footnote 28 Hence, the mainstreaming of gender into trade policymaking becomes an opportunity for the next steps in this regional integration process in order to foster inclusive and sustainable development.

12.3.2 Gender-Specific Policies under the Pacific Alliance

The Pacific Alliance’s Additional Protocol has not yet incorporated specific gender-related provisions.Footnote 29 In 2015, members agreed on a gender approach at the Tenth Summit of the Pacific Alliance. The Gender Technical Working Group (GTG) was created to promote the gender perspective throughout the Alliance, to incorporate women leaders in exports, and to establish virtual platforms to address trade and gender, mainstreaming a gender perspective into cooperation, SMEs, export promotion agencies, the digital agenda, and innovation groups. In the Eleventh Summit, the Presidential MandateFootnote 30 proposed the incorporation of female entrepreneurs into the export process, and the establishment of virtual platforms to promote gender and trade dialogues. Following this, the Alliance commissioned the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to assess gender equality in the member economies.

The 2017 Presidential DeclarationFootnote 31 referred to the contribution of the gender perspective for the fulfilment of the 2030 United Nations’ Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs).Footnote 32 This led to the creation of the Virtual Community of Female Entrepreneurs and the III Forum of female entrepreneurs of Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

In 2018, the Women Entrepreneurs Community platform, which is linked to ConnectAmericas, was established. The work under this initiative is complemented by Mujeres del Pacífico (Women of the Pacific), a private initiative that works with the Chilean Economic Development Agency (CORFO), the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and the Association of Entrepreneurs of Latin America (ASELA) through its Multilateral Investment Fund. In the same year, the Pacific Alliance Observatory issued a report identifying women-oriented programmes.Footnote 33 This report displayed the differences in the number of women-favouring programmes offered by each country, Colombia (twenty-three), Chile (fourteen), Mexico (eleven), and Peru (three), and highlighted that only 18 per cent of them referred to the need to mitigate sexist stereotypes.

In 2019, to clarify the understanding of concepts such as discrimination and gender equality, amongst others, the GTG created the Gender Glossary.Footnote 34 The GTG with IADB conducted a survey of 1933 women-owned businesses in Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Preliminary results, presented at the Pacific Alliance Webinar on Women and International Trade in 2020, show that 78 per cent of surveyed businesswomen were sole/majority shareholders of companies, out of which 73 per cent were micro companies, 20 per cent small, 5 per cent medium, and 2 per cent were big enterprises.Footnote 35 Services, food, and beverage industries constitute the majority of sectors in which they work, except in Peru, where textiles and clothing are key industries where women engage as entrepreneurs and business-owners.

In 2020, the GTG launched the Guidelines for the Use of Inclusive Language in Technical Groups of the Pacific Alliance.Footnote 36 The study, with IADB, was expanded to include the effects of the COVID-19 crisis. The Pacific Alliance countries conducted a series of webinars to support the digitalization of women’s businesses and issued a Presidential Declaration on Gender Equality with a Roadmap for Women’s Autonomy and Economic Empowerment.Footnote 37 This roadmap reiterated the role of international agreements regarding women’s rights and commits to centring women in reactivation strategies and economic recovery. Additionally, the roadmap identifies priority actions to promote women’s entrepreneurship, labour participation, access to leadership positions, and decision-making in the political, economic, and social spheres; eliminate barriers to women’s autonomy; reduce the gender digital gap; and generate gender-disaggregated data.

Therefore, the Pacific Alliance has recognized the relevance of mainstreaming gender for sustainable development in its presidential declarations, technical groups, and the Roadmap for Women’s Autonomy and Economic Empowerment. However, current programmes should move into solid commitments included within the Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (trade protocol), giving stability and permanence to the objective of gender equity.Footnote 38

12.4 Gender Mainstreaming in South American Trade Agreements

The inclusion of a gender perspective has been a latecomer in bilateral trade agreements. Whereas the word ‘women’ has been used to address gender issues in the past, the expression ‘gender’ has only appeared recently.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, the evolution of the language from ‘women’ to ‘gender’ is correlated with the progressive development of the gender mainstreaming paradigm, which flourished after the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action.Footnote 40

Although some WTO members have included provisions on gender in their FTAs, the scope, the form, and the enforceability of these provisions have been diverse. As of December 2020, from the 577 PTAs notified to the WTO, 83 (14 per cent) of them include at least one provision related to gender, and 257 (44 per cent) refer implicitly to gender impacts.Footnote 41 Regarding commitments, some agreements have a single clause on substantial duties for the contracting parties, while others have a dedicated chapter on gender. However, such provisions and chapters are not legally binding. While most of these clauses are included in the main text of the agreements, some clauses are tucked away in subsidiary agreements, appendices, or protocols. Reaffirmation provisions, for example, require members to repeat legal obligations made under other international treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), ILO conventions, or the UN SDGs.Footnote 42 Within South America, countries such as Chile and Uruguay have suggested a new paradigm in which free trade agreements are viewed as tools for attaining women’s economic empowerment.Footnote 43

Within this context, the opportunities of negotiations with like-minded countries have led to the creation and inclusion of gender chapters within free trade agreements. This has represented a shift in the way gender equality issues were treated within trade agreements, as in previous trade agreements parties usually made a reference to gender issues in the preambles of the agreements or only addressed them as a general issue.Footnote 44 For instance, the Chile–Vietnam FTA (2014) proposes gender as one of the spheres of cooperation within its cooperation chapter,Footnote 45 and the Peru–Australia FTA (2020) refers to women and economic growth within its development chapter.Footnote 46 In the provision titled ‘Women and Economic Growth’, the contracting parties in this agreement have recognized the necessity to enhance opportunities for women so as to contribute to economic development, for which it promotes cooperation activities that will improve the ability of women to fully access and benefit from the opportunities created by the agreement.

The Chile–Uruguay FTA (2016)Footnote 47 marked the first inclusion of a dedicated chapter on gender and trade in the framework of a bilateral FTA. In the case of Chile, gender became an explicit component of trade policy during Michelle Bachelet’s second government (2014–2018). The relevance of this topic during her administration was based on two main elements: (i) women’s role as supporters of the economy; and (ii) the lack of information, discussion, proposals, and institutional participation. In addition to the Ministry of Women and Gender Equity created in 2016,Footnote 48 in terms of trade policy formulation and implementation, the General Directorate of International Economic Relations (DIRECON) included a gender-perspective approach in its work agenda,Footnote 49 to identify relevant spaces where gender-sensitive measures could be addressed.Footnote 50 In the case of Uruguay, under the second mandate of President Tabaré Vasquez (2015–2020), a process of bilateral free trade agreements negotiated outside Mercosur was initiated.Footnote 51 Both governments’ coalitions had a progressive agenda in place, which gave gender issues a prominent position within their public policies. This created suitable conditions for the inclusion of a gender chapter in their bilateral FTAs.

Following the Chile–Uruguay agreement, Chile incorporated gender issues in its negotiation processes. The agreements between Canada and Chile (June 2017), Argentina and Chile (November 2017), Brazil and Chile (December 2018), and Chile and Ecuador (August 2020) each included a trade and gender chapter.Footnote 52 The Chile–Canada FTA is a modernized version of the 1997 agreement, which corresponds to a progressive trade agenda as a response to the worldwide rise of anti-globalization populism and the concentration of trade gains at the top of the income scale that have left women, among others, behind.Footnote 53 The Chile–Uruguay FTA, Argentina–Chile FTA, and Brazil–Chile FTA are established in the context of the Economic Complementation Agreement 35 among Chile and Mercosur parties.Footnote 54 In particular, the Chile–Brazil FTA includes a framework of good regulatory practices in order to promote an open, fair, and predictable environment for companies in Chile and Brazil,Footnote 55 in order to respect, amongst others, issues relating to the environment and gender issues. Regarding the Chile–Ecuador FTA, the objective of modernizing the existing agreement was to include new issues related to trade in services and to achieve a deeper level of integration, comprising an inclusive approach under which gender provisions were incorporated.

In a multilateral arena, in 2018, Canada, Chile, and New Zealand established the Inclusive Action Group (ITAG) to create progressive and inclusive trade policies to guarantee that benefits from trade and investment are equally distributed. In 2020, they signed the Global Trade and Gender Arrangement (GTAGA) to stimulate women’s participation in international trade, recognizing the relevance of having a gender perspective in the promotion of an inclusive economic growth.Footnote 56 This agreement acknowledges parties’ equality laws and regulations, calling on members not to weaken or reduce their protection in order to increase their trade and investment benefits. The three countries, by signing this agreement, have sought to ensure that trade policies are inclusive and that they become more inclusive with time, which is relevant for the post-pandemic economic recovery. The agreement’s coverage has expanded as Mexico (6 October 2021), Colombia (13 June 2022), and Peru (13 June 2022) have acceded to it.

Moreover, the ongoing trade negotiation mandates on several FTAs including Canada–Mercosur, Chile–European Union, Chile–South Korea, Chile–Paraguay, and the associate members of the Pacific Alliance include trade and gender issues (Figure 12.1). As these negotiations are still in process, it is not clear which instrument or approach will be used to establish commitments on gender issues. Nevertheless, during the field research, interviewees expressed that it was most likely that trade and gender chapters would be used, following the templates of previous FTAs.Footnote 57 The consideration of gender chapters in the ongoing negotiations highlights the instrumental role that gender policies may play towards a sustainable socioeconomic development and reinforce the parties’ commitment to effectively implement their normative policies and good practices towards gender equality and equity.Footnote 58

Figure 12.1 Timeline of South America’s gender references in trade agreements.

12.5 Assessment of Gender Issues in South American FTAs

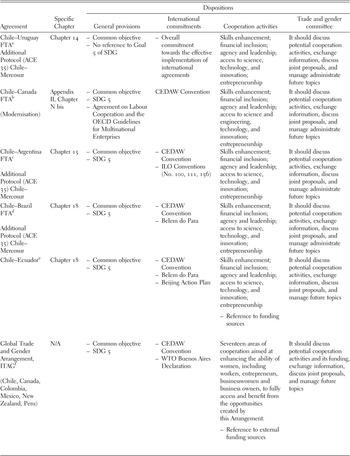

In order to understand how South American economies have mainstreamed gender issues, the trade and gender chapters in FTAs, as well as those in the GTAGA, are reviewed. This section provides an assessment of their content, their enforcement, and their governance.Footnote 59 Table 12.1 presents a detailed comparison of the agreements’ texts in the following dispositions: general provisions, international commitments, cooperation activities, and the establishment of trade and gender committees.Footnote 60

Table 12.1 Gender and trade provisions in South American FTAs

| Agreement | Specific Chapter | Dispositions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General provisions | International commitments | Cooperation activities | Trade and gender committee | ||

Chile–Uruguay FTAFootnote a Additional Protocol (ACE 35) Chile–Mercosur | Chapter 14 |

|

| Skills enhancement; financial inclusion; agency and leadership; access to science, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship | It should discuss potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage administrate future topics |

Chile–Canada FTAFootnote b (Modernisation) | Appendix II, Chapter N bis |

| CEDAW Convention | Skills enhancement; financial inclusion; agency and leadership; access to science and engineering, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship | It should discuss potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage administrate future topics |

Chile–Argentina FTAFootnote c Additional Protocol (ACE 35) Chile–Mercosur | Chapter 15 |

|

| Skills enhancement; financial inclusion; agency and leadership; access to science, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship | It should discuss potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage administrate future topics |

Chile–Brazil FTAFootnote d Additional Protocol (ACE 35) Chile–Mercosur | Chapter 18 |

|

| Skills enhancement; financial inclusion; agency and leadership; access to science, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship | It should discuss potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage administrate future topics |

| Chile–EcuadorFootnote e | Chapter 18 |

|

| Skills enhancement; financial inclusion; agency and leadership; access to science, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship

| It should discuss potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage future topics |

Global Trade and Gender Arrangement, ITAGFootnote f (Chile, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru) | N/A |

|

| Seventeen areas of cooperation aimed at enhancing the ability of women, including workers, entrepreneurs, businesswomen and business owners, to fully access and benefit from the opportunities created by this Arrangement.

| It should discuss potential cooperation activities and its funding, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage future topics |

a Government of Chile, ‘Chile–Uruguay FTA’ <www.subrei.gob.cl/docs/default-source/acuerdos/uruguay/capitulos-uruguay/14-capitulo-14-g%C3%A9nero-y-comercio.pdf?sfvrsn=962199b6_2> accessed 19 April 2022.

b Government of Chile, ‘Chile–Canada FTA’ <www.subrei.gob.cl/docs/default-source/acuerdos/canad%C3%A1/modernizaci%C3%B3n-del-acuerdo/acuerdo-modificatorio-inversiones-genero-y-comercio.pdf?sfvrsn=2c5ae24d_2> accessed 8 May 2022.

c Government of Chile, ‘Chile–Argentina FTA’ <www.subrei.gob.cl/docs/default-source/acuerdos/argentina/capitulos-argentina/15-capitulo-15-g%C3%A9nero.pdf?sfvrsn=8326c19d_2> accessed 8 May 2022.

d SICE - OAS, ‘Chile–Brazil FTA’ <www.sice.oas.org/TPD/BRA_CHL/FTA_CHL_BRA_s.pdf> accessed 8 May 2022.

e SICE – OAS, ‘Chile–Ecuador FTA’ <www.sice.oas.org/Trade/CHL_ECU/Cap_18_s.pdf> accessed 8 May 2022.

f Government of Canada, ‘GTGA’ <www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/inclusive_trade-commerce_inclusif/itag-gaci/arrangement.aspx?lang=eng> accessed 8 May 2022.

12.5.1 Content

As the GTAGA is the most recent agreement and is solely focused on trade and gender, it is not surprising that it contains more gender-related sections. This agreement includes new sections focused on deepening commitments. For instance, Section 5 titled ‘Gender and Responsible Business Conduct’ aims for the parties to incorporate the principles of internationally recognized standards that address gender equality in their jurisdictions. Section 6 titled ‘Discrimination in the Workplace’ focuses on the participants that support the goal of promoting gender equality in the workplace. Section 7 titled ‘Transparency’ and Section 10 titled ‘Trade and Gender Working Group’’ have been created to define the actions of the working group in gender cooperation. Finally, Section 13 refers to parties’ options to invite other economies interested in pursuing inclusive trade and investment approaches to join them. Following this provision, in the context of the 2021 OECD Trade Ministers’ meeting, Mexico was formally accepted into the GTAGA.Footnote 61

It must be stated that the five agreementsFootnote 62 analysed in this section were accomplished in a short period of time, and that they have a very similar structure. Moreover, they went through an important imitation process, being the first agreements and providing a template for those that followed. In this regard, they share the same structure. In general, the sections contained in all agreements, except for the GTAGA, are: ‘General Provisions’, ‘International Commitments’, ‘Cooperation Activities’, ‘Trade and Gender Committee’, ‘Consultations’, and ‘Non-application of Dispute Resolution’. In fact, these agreements not only share a similar structure, but the content of the legal texts is almost identical. This is not a new phenomenon in the negotiation of trade agreements, which are usually settled using common templates.Footnote 63

Even though the chapters contain some mandatory elements, none of them requires a change in domestic regulations, as they mainly refer to cooperation activities. The chapters, within their general provisions, acknowledge the importance of incorporating a gender perspective into the promotion of inclusive economic growth. Moreover, they reaffirm parties’ commitments towards multilateral conventions, such as equal pay for equal work, maternity protection, and the balance of family and professional life.

In the Canada–Chile FTA, the Argentina–Chile FTA, the Brazil–Chile FTA, the Chile–Ecuador FTA, and the GTAGA, as stated by a high-level government official,Footnote 64 agreements were reached to carry out Goal 5 of the SDGs. A mention of the SDGs was omitted in the Chile–Uruguay FTA, as the SDGs were just being implemented at the time the agreement was negotiated. In this vein, scholastic research argues that mainstreaming gender in trade policy is deemed a vehicle and an accelerator for achieving the SDGs,Footnote 65 since trade policy has a vital role in promoting many other SDGs in addition to SDG 5 on gender equality, such as alleviation of poverty (SDG 1), improvement of education (SDG 4), promotion of decent working conditions for economic growth (SDG 8), and reduction of inequalities (SDG 10).

Within the ‘General Provisions’, the recognition that increasing labour participation, decent jobs, and economic autonomy of women contribute to sustainable economic development is part of all agreements. Nevertheless, they differ in how the provision is incorporated according to the parties’ international commitments. For instance, the Chile–Canada FTA and the GTAGA reaffirm the work done in OECD, which is not included in the other FTAs because Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Uruguay are not members of the OECD.

An interesting difference within the agreements can be found in their second section, titled ‘International Agreements’. The Chile–Uruguay FTA only refers to an overall commitment towards the effective implementation of international agreements. The agreements between Chile and Canada, Argentina and Chile, Chile and Ecuador, Brazil and Chile, and the GTAGA explicitly include the CEDAW; and Argentina also includes references to ILO Conventions on remuneration equity (No. 100), on work and occupation discrimination (No. 111), and on workers’ family responsibilities (No. 156). As the GTAGA was signed after the 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference, it recalls the objectives of the WTO Joint Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment and refers to the implementation of ‘obligations under any other international agreements addressing women’s rights or gender equality to which they are party’ (Article 3.b). As explained by a high-level government official, this shows the quick evolution of gender-related chapters, and that countries have managed to include specific references to relevant international gender-related agreements in a short time. For instance, the Chile–Brazil FTA and the Chile–Ecuador FTA recall the Belem do Para Convention.Footnote 66 Chile and Ecuador have also made a commitment in their bilateral FTA to implement the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on the rights of women and girls and their empowerment. In this way, FTAs may signal the importance of various international treaties towards the accomplishment of a general well-being objective.

In terms of ‘Cooperation Activities’, all the above-mentioned FTAs as well as the GTAGA include almost identical provisions. This is the core of the trade and gender chapters, with activities that can be beneficial for women, considering areas such as skills enhancement; financial inclusion, agency, and leadership; access to science, technology, and innovation; entrepreneurship; and with respect to how trade and gender provisions are to be treated in the relevant chapters of the agreement. In addition, the Chile–Vietnam FTA and the Peru–Australia FTA also included ‘gender’ directly in their cooperation activities.

Nevertheless, it must be highlighted that the trade and gender chapters do not include a specific programme on cooperation, and do not define budgets, baselines, targets, objectives, measurements, or other relevant characteristics to enforce the cooperation. In this sense, cooperation activities are subject to the will of in-office administrations. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the most recent agreements (GTAGA and the Chile–Ecuador FTA) explicitly refer to parties’ commitments to find international donors, private sector entities, and NGOs to assist in the development and implementation of cooperation activities.

The chapter on trade and gender in the Chile–Canada FTA is the only FTA which contains sections on ‘Relation to the Agreement on Labour Cooperation’ and ‘Definitions’. With respect to labour cooperation, the section states that if there is any inconsistency between the chapter and the Agreement on Labour Cooperation or its successor, the latter will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency. Regarding ‘Definitions’, the Agreement on Labour Cooperation and the Agreement on Environmental Cooperation are defined and contextualized. Hence, there is a clear priority given to labour provisions over gender issues in this agreement.

12.5.2 Enforcement

One of the most important articles examined is the final provision within these chapters on the ‘Non-application of Dispute Resolution’. Amongst international treaties, a crucial characteristic of trade agreements has been their lack of enforceability. This has been possible due to the exclusion of these provisions and chapters from the jurisdiction of the agreements’ dispute resolution mechanisms that could use the annulment of trade preferences as a leverage mechanism to ensure parties’ compliance. As stated in Article 14.6 of the Chile–Uruguay FTA, Article N bis-06 of the Chile–Canada FTA, Article 15.6 of the Chile–Argentina FTA, Article 18.9 of the Chile–Ecuador FTA, and Article 18.7 of the Chile–Brazil FTA, no party may initiate a dispute for a breach of gender-related provisions.

It can be argued that such an exclusion makes the commitments on gender hortatory in nature. Therefore, the effective implementation of ‘International Agreements’ or ‘Cooperation activities’ are left to the willingness of the parties (and incumbent administrations), as the breach of gender-related provisions is not subject to any kind of retaliation. In this context, two lines of thought were encountered during the interviews.Footnote 67 On the one hand, some interviewees, especially from the public sector, argue that as the main impact of the inclusion of gender chapters in FTAs may not be on trade relations, the mere inclusion of a chapter reflects government’s willingness to incorporate and visualize this topic, which validates a gender perspective within trade policy agendas. On the other hand, interviewees from academia and international organizations have pointed out that including current chapters to the dispute settlement mechanism is not useful as they do not contain strong provisions to be enforced and they are built on cooperation activities without concrete legal commitments.

This situation is very similar to the evolution of environmental and labour clauses within trade agreements, which, at the beginning, were included as side agreements. However, they are now becoming a substantial part of trade negotiation agendas. The same can be argued for regulations relating to trade in services, which have been included at the multilateral level since the Uruguay Round negotiations that established the WTO (1986–1994). However, during the 1990s, not every economy wanted to include them in their bilateral treaties. Nowadays, almost every trade agreement includes not only a trade-in-services chapter, but also specific services-related chapters such as financial services, telecommunication services, movement of businesspersons, digital trade, amongst others. Therefore, it is not unlikely that new agreements may include gender-related chapters, with enforceable provisions.

12.5.3 Governance

In each of the above-mentioned FTAs, a Trade and Gender Committee is established to manage the possible outcomes of the agreement in areas such as potential cooperation activities, exchange information, discuss joint proposals, and manage any other related topic that may arise in the future.Footnote 68 This committee is supposed to meet at least once a year and it should review the implementation of the chapter after two years. Regarding the ‘Consultations’ section, the five chapters state that the contracting parties will make all necessary efforts to solve any issues that may arise regarding the chapter’s application and interpretation, through consultations and dialogue.Footnote 69 The GTAGA states that each participant will designate a contact point for trade and gender to coordinate the implementation of this arrangement.Footnote 70 Even though it contains the section on ‘Differences in interpretation and implementation’, it only states that participants should resolve any differences on the interpretation or application of this arrangement amicably and in good faith. However, there are no proper mechanisms set up for the consultation processes. The most advanced provisions in this respect can be found in the Chile–Ecuador FTA, which entered into force in May 2022. This agreement not only defines contact points and functions but also provides for a consultation procedure.Footnote 71 This process is based on a mutually satisfactory resolution establishing timelines for each step. First, the affected party will present a request through contact points to solve the matter; if it is not solved, the request is transferred to the committee; and in case there is no resolution, it may be raised to the related ministers. At any step, good offices and conciliation can be used, and if an agreement is reached, the final report will be publicly available.

As the discussions show, these chapters have made various strides in mainstreaming gender in trade agreements, but they have various deficiencies. First, instead of including specific gender-related standards that could affect trade under the agreements, reference is made to the implementation of gender equality commitments included in global conventions. Second, milestones or specific goals are not included. Third, dispute-settlement mechanisms do not apply to such provisions. Fourth, the harmonization of gender-related legislation between the parties is not mandated. Fifth, potential impacts of trade liberalization pursued under the agreements on women’s well-being and economic empowerment are not addressed or mentioned in these agreements.Footnote 72

12.6 Conclusion

In South America, a gender perspective has been included in foreign affairs as well as in trade policies. The region has pioneered the incorporation of gender in trade policies, including in both trade negotiations and trade promotion. This is particularly true in the case of Chile. This chapter has analysed how South American economies have mainstreamed gender issues in their trade agreements, identifying their common elements and evolution. For this purpose, the chapter has reviewed the incorporation of gender provisions in bilateral trade agreements, Mercosur, and the Pacific Alliance.

At a regional level, both Mercosur and the Pacific Alliance have incorporated gender issues into their working agendas. Nevertheless, most of the work related to gender has been on social or institutional policymaking and not with respect to trade instruments. In other words, trade instruments lack a gender perspective or gender-related provisions, especially in regional economic integration instruments. It has been recognized that incorporating a gender perspective into trade policymaking can aid in achieving inclusive and sustainable development. Moreover, as both Mercosur and the Pacific Alliance have referred to their interest in gender topics, this may become a stepping stone towards regional convergence.Footnote 73

Regarding bilateral agreements, the inclusion of a gender-related chapter has become a common element in the latest agreements that are in operation, such as in the Chile–Uruguay FTA, the Chile–Canada FTA, the Argentina–Chile FTA, the Brazil–Chile FTA, and the Chile–Ecuador FTA. These trade and gender chapters consider trade as an engine for economic growth, thereby improving women’s access to opportunities and removing barriers to enhance their participation in national and international economies, and contributing to sustainable and inclusive economic development, competitiveness, prosperity and society’s well-being. These objectives have been reaffirmed by the GTAGA.

Although legally there is no mechanism to enforce the parties’ commitments on trade and gender, the mere inclusion of gender-related chapters is not only an important step towards guaranteeing that trade may benefit women and men equally, but a representation of an important milestone towards gender equity. First, the inclusion of such chapters is a recognition of the relevance of incorporating a gender perspective within trade negotiations. These chapters take into consideration the relevance of the nexus between trade and gender, and the importance for countries to take actions towards allowing women to benefit from trade liberalization. They identify ways to enhance women’s participation in international trade, as well as the relevance of sound public policies that may be directed to use trade as a tool for achieving gender equity.

Second, the evolution of the chapters’ negotiations allows the relevant elements in the trade and gender relationship to be identified and assessed. As reviewed in this chapter, the Chile–Uruguay FTA does not deepen the legality of commitments in certain provisions. For example, the recent FTAs signed between Brazil and Chile, Chile and Ecuador, and the GTAGA, have shown detailed specifications in certain elements and references to international agreements (such as the UN SDGs, CEDAW, or the ILO conventions). However, the Chile–Uruguay FTA does not refer to any agreement in particular. In this way, as new chapters are negotiated, more specific issues are encompassed within the agreement, allowing the best policies to be formulated.

Third, the evolution of agreements must be taken into consideration. Although at this point gender-related chapters are not subject to dispute-resolution mechanisms, agreements do evolve. For instance, the FTAs between Chile and Canada, and Chile and Ecuador have been outcomes of a renegotiation process of their predecessors. This evolution must be considered for each agreement, and for trade negotiations in general. As new topics arise, they are initially included as side agreements or non-enforceable chapters (which is the case for gender chapters). However, once the topic is more widely accepted by the international community as relevant and important, new agreements are more likely to include these topics as binding and enforceable commitments.

Nevertheless, for trade policy instruments to be drivers for women’s economic empowerment, it is necessary to strengthen commitments, elaborate concrete programmes for the development of cooperation activities, and conduct periodical ex ante and ex post assessments. Trade and gender chapters should not only contain declarative provisions, but also obligations to undertake regulatory changes at the domestic level and guarantee their compliance. Moreover, cooperation activities, which are the core of these agreements, need to be planned accordingly, for which timelines, specific activities, areas to cover, and budgets are required. Besides, for countries to improve women’s participation in trade, women’s presence in each economic sector should be studied and acknowledged through sex-disaggregated data. This will become the first step towards conducting quantitative and qualitative assessments to see the expected impacts of trade policies on women, as well as the actual changes in the economy after their implementation.