Impact statement

Despite a rise in emphasis on the social mandate of sustainable development discourse, there is much uncertainty regarding the many meanings and applications of the term ‘social sustainability’. This has meant that, like other industries, the seafood sector has been criticised for neglecting social issues. In this review, we provide a broad overview of the current state of knowledge relating to social sustainability in the seafood sector (comprising fisheries and aquaculture). We also identify where research gaps remain. We also propose means by which social sustainability can be incorporated into existing industry and governance processes. We anticipate that this review will be of benefit in two ways to inform: i) those working in social sustainability in the seafood sector and associated organisations regarding potential areas on which to focus their efforts and ii) scholars regarding directions for future research.

Introduction

Sustainability and sustainable development are the buzzwords of our era, partly due to the Sustainable Development Goals, formulated in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly and adopted as Agenda 2030. Nowhere is this clearer than in primary production/extraction industries, such as aquaculture and fisheries. Seafood is the world’s most widely traded food commodity (Kittinger et al., Reference Kittinger, Teh, Allison, Bennett, Crowder, Finkbeiner, Hicks, Scarton, Nakamura and Ota2017), and comprises 17% of the world’s total global animal protein consumption (I FAO, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, 2022). In recent years, the pressure for the seafood sector (comprising fisheries and aquaculture industries) to become more sustainable (environmentally, economically and socially) has substantially increased (Portney, Reference Portney2015; Osmundsen et al., Reference Osmundsen, Amundsen, Alexander, Asche, Bailey, Finstad, Olsen, Hernández and Salgado2020), partly due to increasing public concerns around environmental impact (Olsen and Osmundsen, Reference Olsen and Osmundsen2017; Graziano et al., Reference Graziano, Fox, Alexander, Pita, Heymans, Crumlish, Hughes, Ghanawi and Cannella2018). Yet the dimension we know the least about regarding seafood sustainability is the social; indeed, the problem of how to understand social sustainability has dogged the social science research agenda for decades (Jacobsen and Delaney, Reference Jacobsen and Delaney2014). Due to various issues, such as its intangible and qualitative nature, social sustainability is often the vaguest and least explicit dimension (Ballet et al., Reference Ballet, Dubois and Mahieu2011; Vifell and Soneryd, Reference Vifell and Soneryd2012; Foran et al., Reference Foran, Butler, Williams, Wanjura, Hall, Carter and Carberry2014; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Anderson, Chu, Meredith, Asche, Sylvia, Smith, Anggraeni, Arthur and Guttormsen2015; Eakin et al., Reference Eakin, Connors, Wharton, Bertmann, Xiong and Stoltzfus2017; Béné et al., Reference Béné, Oosterveer, Lamotte, Brouwer, de Haan, Prager, Talsma and Khoury2019). Some scholars have tried to unravel the situation (e.g. Vallance et al., Reference Vallance, Perkins and Dixon2011), while others have explored a variety of parallel approaches such as corporate social responsibility, the triple bottom line and social licence to operate (e.g. Dahlsrud, Reference Dahlsrud2008; Alibašić, Reference Alibašić2018; Alexander and Abernethy, Reference Alexander and Abernethy2019).

Marine and coastal resources provide humans with various economic, nutritional and sociocultural functions (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). Traditionally, fisheries management and governance of coastal and nearshore ecosystems were focused primarily on maintaining biological sustainability within an ecological framework. However, the integration of social sustainability, human dimensions and human rights-based fisheries into international law and conservation policy has increased recognition of the importance of human wellbeing outcomes (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Katz, Yadao-Evans, Ahmadia, Atkinson, Ban, Dawson, de Vos, Fitzpatrick and Gill2021). Advancing democratic ocean governance through recognitional, representational and distributive justice is a key reason for a rise in the study of individual social sustainability loosely covered by the term ‘wellbeing’ (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). Indeed, wellbeing and quality of life have become what social sustainability seeks to achieve, and the literature in this space has increased significantly in the last decade with most studies attempting to quantify and qualify these concepts (Bravo-Olivas et al., Reference Bravo-Olivas, Chávez-Dagostino, Malcolm and Espinoza-Sánchez2015), although it is not clear what change this has yet led to. Wellbeing has traditionally been inferred from economic indicators under the hypothesis that a healthy economic is related to societal wellbeing (ibid.). More recently, however, wellbeing in the literature relates to fairness, equity and justice based on the representation of different groups and individuals in decision-making processes, but also to the consideration of diverging views, beliefs, interests and needs, and how input is weighted (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Diederichsen, Fullbrook, Lombard, Rees, Rivers, Snow, Strand, Zuercher and Niner2023).

Social sustainability in the seafood sector has tended to focus on wellbeing at the group level, viewing fishers or fish/shellfish/seaweed farmers as a collective, a community, rather than as a collection of individuals (Aguado et al., Reference Aguado, Segado and Pitcher2016). This has meant that what Krause and co-authors call a ‘people-policy gap’ remains (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Brugere, Diedrich, Ebeling, Ferse, Mikkelsen, Agúndez, Stead, Stybel and Troell2015), as social sustainability at the individual level is rarely considered as a goal in and of itself (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Diederichsen, Fullbrook, Lombard, Rees, Rivers, Snow, Strand, Zuercher and Niner2023). The socio-economic dimensions that make up individual social sustainability in the marine environment include gender, employment and income, nutrition, food security, health, insurance, credit availability, human rights, legal security, privatisation, culture/identity, global trade and inequalities, as well as policies, laws and regulations, the macroeconomic context, political context, customary rules and systems, stakeholders, knowledge and attitudes, ethics, power, markets, capital and ownership (Hishamunda et al., Reference Hishamunda, Ridler, Bueno and Yap2009; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Amundsen and Osmundsen2020; Leposa, Reference Leposa2020; Osmundsen et al., Reference Osmundsen, Amundsen, Alexander, Asche, Bailey, Finstad, Olsen, Hernández and Salgado2020; Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). This must be added to the broader community-centred approach to understanding sustainability which includes dimensions such as participation in community and decision-making that affects the community, relationships and trust of others leading to social capital – if we want to understand social sustainability in its broadest sense.

We undertook a ‘rapid review’ (a review in which design decisions are taken to reduce the time taken to undertake a traditional systematic review) to identify what is currently known about the social sustainability of the seafood sector. There are several limitations to this approach including that the search is less comprehensive, there is non-blinded appraisal and selection, and this may lead to biases in the included articles. We conducted a search using the terms ‘social sustainability’ AND ‘aquaculture’ or ‘fisheries’ OR ‘seafood’, but we did only search using the English language. We searched in three databases including ScienceDirect, JSTOR and Discovery. Articles were excluded if the term ‘social’ was mentioned but was not a focus. Using this process, we identified 113 relevant articles. These articles were entered into NVivo and subject to an inductive thematic analysis. Using this approach, we identified seven key thematic areas: livelihoods and human development; human rights; social, psychological and cultural needs; equitable access to resource and benefit sharing; a voice in public issues; flow-on benefits for local and regional economies and improved infrastructure and access. Despite the limitations of the method, the authors believe these themes to be comprehensive based on expertise of research in this field.

Livelihoods and human development

Employment is more than just the number of people employed – it can be directly or indirectly related to improvements in quality of life, immigration, demographics, access to/improved health care and consumption of natural resources and includes heritage, lifestyle and healthy living in coastal communities (Aguado et al., Reference Aguado, Segado and Pitcher2016; Asche et al., Reference Asche, Garlock, Anderson, Bush, Smith, Anderson, Chu, Garrett, Lem, Lorenzen, Oglend, Tveteras and Vannuccini2018; Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). Employment has also been the largest focus for any investigations into social sustainability in the seafood sector.

In fisheries research, it is often noted that jobs are decreasing, due to the inability to bring youth into the sector (Symes and Phillipson, Reference Symes and Phillipson2009; Tam et al., Reference Tam, Chan, Satterfield, Singh and Gelcich2018) and the ‘greying of the fleet’ (Tam et al., Reference Tam, Chan, Satterfield, Singh and Gelcich2018; Donkersloot et al., Reference Donkersloot, Coleman, Carothers, Ringer and Cullenberg2020; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Ogier, Hobday, Thomas, Hartog and Haas2020). Alternatively, aquaculture is frequently lauded for its job creation opportunities (e.g. Pierce and Robinson, Reference Pierce and Robinson2013; Aarstad et al., Reference Aarstad, S-E and Fløysand2023), however whether this happens at the level industry proposes is debated (Alexander, Reference Alexander2022). Livelihoods are frequently discussed in an artisanal fisheries or local community context against a background of change and increasing vulnerability and the need for communities to diversify and local people to secure jobs (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). In the seafood sector, it is also not uncommon to see family and kin supporting small-scale operations in places such as Alaska (Donkersloot et al., Reference Donkersloot, Coleman, Carothers, Ringer and Cullenberg2020), Brazil (Glaser and Diele, Reference Glaser and Diele2004), Cambodia (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Rimmer, Hoy and Thay2022) and India (Adiga et al., Reference Adiga, Ananthan, Kumari and Ramasubramanian2016; Apine et al., Reference Apine, Turner, Rodwell and Bhatta2019).

The question of gender, age and race have been explored in the social sustainability literature – particularly in relation to employment (e.g. in social sustainability indicators used by Valenti et al., Reference Valenti, Kimpara, BdL and Moraes-Valenti2018). Nearly half of the workforce in fisheries is estimated to be female, playing significant but often ‘invisible’ roles as they may be unrecognised, unpaid and underpaid (Freitas et al., Reference Freitas, Gomes, Luis, Madruga, Marques, Baptista, Rosalino, Antunes, Santos and Santos-Reis2007; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Tyzack, Anderson and Onoakpovike2013). Research has shown that the embeddedness of women in a community affected their wellbeing but did not apply in the same way to fishers from the same community. This is because fishers gain their livelihoods offshore while women typically undertake employment in port such as processing, marketing or accounting alongside others from the community (Nicheva et al., Reference Nicheva, Waldo, Nielsen, Lasner, Guillen, Jackson, Motova, Cozzolino, Lamprakis and Zhelev2022). In aquaculture, women may be restricted to certain roles and face other obstacles such as ill-fitting protective clothing, restrictive maternity leave policies and a lack of investment in support such as childcare in rural areas (Kelling and Lawan, Reference Kelling and Lawan2023). Employment in coastal sectors suffers from a lack of gender-disaggregated data (ibid.) but from the data that is available, aquaculture and related marine food producing sectors tend to employ a workforce with low education, which is often seen as a key factor for mobility on the labour market, and which makes them vulnerable to social change (Nicheva et al., Reference Nicheva, Waldo, Nielsen, Lasner, Guillen, Jackson, Motova, Cozzolino, Lamprakis and Zhelev2022). To make marine food sectors more attractive for women and to meet social, psychological and cultural needs, requires evaluating the attractiveness of the industry in general (ibid.). This is why several articles voice either general calls for sociocultural data inclusion, or suggest types of data to be included (Bravo-Olivas et al., Reference Bravo-Olivas, Chávez-Dagostino, Malcolm and Espinoza-Sánchez2015; Van Holt et al., Reference Van Holt, Weisman, Johnson, Käll, Whalen, Spear and Sousa2016; Grimmel et al., Reference Grimmel, Calado, Fonseca and de Vivero2019; Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021; Nicheva et al., Reference Nicheva, Waldo, Nielsen, Lasner, Guillen, Jackson, Motova, Cozzolino, Lamprakis and Zhelev2022). In regards to age, in the EU-28 (28 countries within the EU that operate as an economic and political block), every third employee in aquaculture is younger than 40 and in fish processing 42% of employees are less than 40 years old but the workforce is less educated than the overall EU-28 working population (Nicheva et al., Reference Nicheva, Waldo, Nielsen, Lasner, Guillen, Jackson, Motova, Cozzolino, Lamprakis and Zhelev2022).

Fair and equal conditions for all in aquaculture/fisheries and supporting industries regardless of gender, nationality or age is constitutionally embedded in the EU (article 21–23, EU charter 2012) (EU 2012), but social sustainability often receives a lower priority in both policy development and research to fill knowledge gaps (Gollan et al., Reference Gollan, Voyer, Jordan and Barclay2019). As a result, inclusive approaches leading to improved social justice, fundamental to achieving SDGs, are missing (Desiderio et al., Reference Desiderio, García-Herrero, Hall, Segrè and Vittuari2022).

Improved education and skills training are another important feature of human capital and again often used as a social sustainability indicator (e.g. Valenti et al., Reference Valenti, Kimpara, BdL and Moraes-Valenti2018; Tiwari and Khan, Reference Tiwari and Khan2019). However, the role of the seafood sector in this is unclear. The education level of fishers is often below the general population average (Adiga et al., Reference Adiga, Ananthan, Kumari and Ramasubramanian2016; Apine et al., Reference Apine, Turner, Rodwell and Bhatta2019) and in small-scale fisheries company-led education programmes do not exist although they may do in large-scale fisheries (Van Holt et al., Reference Van Holt, Weisman, Johnson, Käll, Whalen, Spear and Sousa2016). In many instances, it is noted that training and other non-formal education is often received by those in the seafood sector and that this does increase their skill and consequently the sustainability of the system (Bailey and Eggereide, Reference Bailey and Eggereide2020; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Kimpara and Valenti2021).

Human rights

For decades, sustainability in seafood supply chains concerned improving traceability from an environmental and food safety perspective, but the ‘social side’ of traceability was overlooked. Global estimates are that at least 40 million people work under coercive or forced labour conditions across industries such as textile, agriculture, construction and fisheries (Tickler et al., Reference Tickler, Meeuwig, Bryant, David, Forrest, Gordon, Larsen, Oh, Pauly, Sumaila and Zeller2018). Human rights abuses such as slavery, forced labour and human trafficking as well as unsanitary conditions, low wages and assault are widespread in fisheries around the world (David et al., Reference David, Bryant and Joudo Larsen2019; Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Boyd, Jackson, Ives and Bales2021). Over the past few years, media attention on human rights violations in the seafood industry have grown (Urbina-Cardona et al., Reference Urbina-Cardona, Cardona and Cuellar2023), adding to existing persistent ecological pressure from overfishing, illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing and climate change (Vandergeest and Marschke, Reference Vandergeest and Marschke2020; Wilhelm et al., Reference Wilhelm, Kadfak, Bhakoo and Skattang2020; FAO, 2022).

Human rights and labour abuses are not restricted to IUU fishing (EJF, 2010; Selig et al., Reference Selig, Nakayama, Wabnitz, Österblom, Spijkers, Miller, Bebbington and Decker Sparks2022) and plenty of evidence exists of exploitation, lack of safety at sea, overwork, non-payment of wages, bonded labour, unfair recruitment, not fit-for-purpose visa systems, child labour, gender violence and physical abuse (Mackay et al., Reference Mackay, Hardesty and Wilcox2020; Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Boyd, Jackson, Ives and Bales2021; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Bygvraa, Hoque, Klein, Kucukyildiz, Westwood-Booth and Holliday2023). Instead, modern slavery is facilitated by the structures within which fishing takes place (Tickler et al., Reference Tickler, Meeuwig, Bryant, David, Forrest, Gordon, Larsen, Oh, Pauly, Sumaila and Zeller2018). Human rights abuses are just one of multiple injustices experienced by seafood workers that also includes the undermining or denial of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Cisneros-Montemayor, Blythe, Silver, Singh, Andrews, Calò, Christie, Di Franco and Finkbeiner2019; Teh et al., Reference Teh, Caddell, Allison, Finkbeiner, Kittinger, Nakamura and Ota2019). This has led to institutionalised inequality, collectively driving social instability, poverty and resource decline (Kittinger et al., Reference Kittinger, Teh, Allison, Bennett, Crowder, Finkbeiner, Hicks, Scarton, Nakamura and Ota2017).

The seafood industry, especially consumer-facing actors such as retailers, use voluntary, non-governmental, market-based governance tools that include ethical standards, ‘responsible sourcing’ commitments and procurement policies, certification and labelling systems, codes of conduct and guiding frameworks, plus auditing strategies (Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Boyd, Jackson, Ives and Bales2021), to interpret environmental, human rights and labour laws through consumer facing (B2C) or business-to-business labels. They do this to demonstrate ethical leadership, address risks, protect brand reputation, improve business performance and meet regulatory pressures (Kittinger et al., Reference Kittinger, Teh, Allison, Bennett, Crowder, Finkbeiner, Hicks, Scarton, Nakamura and Ota2017). Significant investment by private sector actors has set and enforced norms and standards for a multitude of discrete sustainability goals that allows products to be defined as ‘sustainable’ when owning just one of these characteristics. A truly sustainable product must account for ecological and human wellbeing.

Social, psychological and cultural needs

In the seafood sector, a variety of aspects that bond a community together and promote social mobility are clear. For example, fishing is often linked to the history and tradition of the places in which it occurs (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Courtney, Urquhart and Ross2013; Urquhart and Acott, Reference Urquhart and Acott2013; Ignatius et al., Reference Ignatius, Delaney and Haapasaari2019). On the other hand, aquaculture has been perceived as negatively affecting coastal culture and tradition, by causing an employment switch from traditional to new industrial seafood production (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Caniggia and Read2002) or by disrupting where indigenous fishing activities can be undertaken (Bailey and Eggereide, Reference Bailey and Eggereide2020). Identity is also strongly influenced by the seafood sector in coastal locations. Fishermen individually often identify strongly with their livelihood, but this is seen at a community level also. As an example, the development of the oyster industry in the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia has been found to strengthen community identity by providing visibility to ‘outsiders’ and acknowledging community worth (Pierce and Robinson, Reference Pierce and Robinson2013). The seafood sector has been found to contribute to community spirit and pride (Pierce and Robinson, Reference Pierce and Robinson2013; Reed et al., Reference Reed, Courtney, Urquhart and Ross2013), and to connection to place (Jacobsen and Delaney, Reference Jacobsen and Delaney2014; Ignatius et al., Reference Ignatius, Delaney and Haapasaari2019; Lin and Bestor, Reference Lin and Bestor2020). Other aspects of cultural capital which contribute to social sustainability include food provision (Crona et al., Reference Crona, Van Holt, Petersson, Daw and Buchary2015; Hornborg et al., Reference Hornborg, van Putten, Novaglio, Fulton, Blanchard, Plagányi, Bulman and Sainsbury2019; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Kimpara and Valenti2021), amenity value (Lin and Bestor, Reference Lin and Bestor2020; Alexander, Reference Alexander2022), local and traditional knowledge (Franco-Meléndez et al., Reference Franco-Meléndez, Cubillos, Tam, Hernández Aguado, Quiñones and Hernández2021) and spiritualism (Ignatius et al., Reference Ignatius, Delaney and Haapasaari2019; Wallner-Hahn et al., Reference Wallner-Hahn, Dahlgren and de la Torre-Castro2022).

Whether they are fishers, fish/shellfish farm workers or processors, people in the seafood sector carry out their lives in communities and are members of wider social groups. However, this is an aspect of community capital where much less is known about the influence of the seafood sector. Scholars have noted that choices made around livelihood are rooted in social relationships and community (Donkersloot et al., Reference Donkersloot, Coleman, Carothers, Ringer and Cullenberg2020). In particular, the building of relationships has been identified as a key component of developing a social licence to operate for the seafood sector (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Ogier, Hobday, Thomas, Hartog and Haas2020; Billing et al., Reference Billing, Rostan, Tett and Macleod2021; Alexander, Reference Alexander2022). A key focus of this area has been around social peace and conflict – often caused by marine stakeholders/users (Glaser and Diele, Reference Glaser and Diele2004; Papageorgiou et al., Reference Papageorgiou, Dimitriou, Moraitis, Massa, Fezzardi and Karakassis2021; von Thenen et al., Reference von Thenen, Hansen and Schiele2021). Issues around intergenerational equity have been recognised but not explored (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Klein, Brown, Beger, Grantham, Mangubhai, Ruckelshaus, Tulloch, Watts, White and Possingham2013; Van Holt et al., Reference Van Holt, Weisman, Johnson, Käll, Whalen, Spear and Sousa2016; Lisa Clodoveo et al., Reference Lisa Clodoveo, Tarsitano, Crupi, Pasculli, Piscitelli, Miani and Corbo2022).

Equitable access to resources and benefit sharing

Social sustainability adds an emphasis on relational and collective processes to existing fisheries management and governance mechanisms such as equitable access to resources, sharing of benefits and adherence to human rights and labour laws, many of which are currently absent from high profile documents on the Blue Economy (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Béné, Charles, Johnson and Allison2012; Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021). For example, most seafood certification programmes are established by non-public organisations and remain focused on environmental sustainability, rather than social sustainability, equity or fairness (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021).

Socially legitimising these aspects by giving due consideration to local conditions and culture are key to achieving coastal development objectives (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Brugere, Diedrich, Ebeling, Ferse, Mikkelsen, Agúndez, Stead, Stybel and Troell2015; Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021; Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Di Domenico and Medeiros2020; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Katz, Yadao-Evans, Ahmadia, Atkinson, Ban, Dawson, de Vos, Fitzpatrick and Gill2021). Without this, blind spots to human behaviour in policies and laws, institutional arrangements and enforcement and compliance are created. This can reinforce command and control approaches, giving less attention to the equitable distribution of benefits. Even less attention may be given to aspects of social equity surrounding the development of marine sectors (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021), leading to more inequalities and vulnerabilities (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Di Domenico and Medeiros2020).

A voice in public issues

A sustainable blue economy will only be realised if human wellbeing and justice are placed at its core (Gollan and Barclay, Reference Gollan and Barclay2020; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Katz, Yadao-Evans, Ahmadia, Atkinson, Ban, Dawson, de Vos, Fitzpatrick and Gill2021; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Fairbanks, Murray, Stoll, D’Anna and Bingham2021; Issifu et al., Reference Issifu, Dahmouni, Deffor and Sumaila2023). Nevertheless, ocean policies have been described as equity-blind (Lubchenco and Haugan, Reference Lubchenco and Haugan2023), where wealth and power are largely concentrated in certain states as a result of neo-colonial structures or with large corporations. These powerful actors dominate decision-making processes (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Cisneros-Montemayor, Blythe, Silver, Singh, Andrews, Calò, Christie, Di Franco and Finkbeiner2019, Reference Bennett, Villasante, Espinosa-Romero, Lopes, Selim and Allison2022; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Gephart, Koehn, Nakayama, Payne, Allison, Belhbib, Cao, Cohen, Fanzo and Fluet-Chouinard2022), excluding specific worldviews and alternative development pathways (Blythe et al., Reference Blythe, Armitage, Bennett, Silver and Song2021). When marginalised groups lack a voice in decision-making processes, their needs, perspectives, and rights may be overlooked or disregarded. This can perpetuate inequality, exploitation and unfair practices (Wilhelm et al., Reference Wilhelm, Kadfak, Bhakoo and Skattang2020; Decker Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Matthews, Cardenas and Williams2022). This is particularly the case for small-scale fishers, who make up 95% of the world’s 4.1 million fishers, and who are often excluded from key decision-making processes, despite contributing to the food security of around 4 billion consumers globally. Bringing human wellbeing and social equity into current ocean governance is the only way to achieve true social sustainability in the future (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Reygondeau, Cheung, Crosman, González-Espinosa, Lam, Oyinlola, Singh, Swartz and Zheng2021; Blythe et al. Reference Blythe, Armitage, Bennett, Silver and Song2021).

Across the seafood sector, concerns have been raised regarding the failures of existing regulatory regimes to incorporate local voice (Ignatius et al., Reference Ignatius, Delaney and Haapasaari2019Billing et al., Reference Billing, Rostan, Tett and Macleod2021; Doerr, Reference Doerr2021; Franco-Meléndez et al., Reference Franco-Meléndez, Cubillos, Tam, Hernández Aguado, Quiñones and Hernández2021; Alexander, Reference Alexander2022) although it is often unclear how communities have engaged in the process to campaign for change. Equity and justice in decision-making has been a key focus of research, with many scholars proposing that adequate access to the information and tools needed to effectively participate in and influence decision-making is key (Halpern, Reference Halpern2003; Jacobsen and Delaney, Reference Jacobsen and Delaney2014; Hadjimichael, Reference Hadjimichael2018). In some cases, those that are affected most by decisions relating to the seafood sector are not involved, for example, crab collectors in a mangrove crab fishery in Brazil were found not to be included in the planning and implementation of fishery management (Glaser and Diele, Reference Glaser and Diele2004). The need to include local knowledge and local perspectives to increase social sustainability has also been noted (Jacobsen and Delaney, Reference Jacobsen and Delaney2014) and indeed was found to improve social sustainability for Territorial Use Rights for Fisheries in Chile (Franco-Meléndez et al., Reference Franco-Meléndez, Cubillos, Tam, Hernández Aguado, Quiñones and Hernández2021).

More often than not, too little attention has been given to the ways individuals will gain, lose or be excluded from coastal development. Most social sustainability issues are not considered in isolation which arguably reflects the multifaceted nature of social sustainability as well as the mix of analytical and normative approaches in the literature (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). However, they all point to the power and role of human agency (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Béné, Charles, Johnson and Allison2012), covering the areas of wellbeing; livelihoods and human development (material assets and basic needs); and social, psychological and cultural needs (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). Power asymmetry through exclusionary processes tend to legitimise predetermined outcomes, which can decrease recognition and representation (ibid.). When participation in management increases, the wellbeing of society is also improved (Datta et al., Reference Datta, Chattopadhyay and Guha2012). Recognition of diverse social and cultural values and different forms of knowledge is key, and emphases the close connection between different aspects of social sustainability (Gilek et al., Reference Gilek, Armoskaite, Gee, Saunders, Tafon and Zaucha2021). However, even when people affected are clearly identified, a policy for systematically including them in often lacking (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Brugere, Diedrich, Ebeling, Ferse, Mikkelsen, Agúndez, Stead, Stybel and Troell2015).

Flow-on benefits for local and regional economies

Often of interest regarding social sustainability of the seafood sector is the input that it has into local, regional, and national economies – all of which contribute tax income to local, regional, and national governments. Benefits to the economy are common in industry and government discourses, although resistance movement discourses suggest that this effect tends to be over-exaggerated (Crona et al., Reference Crona, Van Holt, Petersson, Daw and Buchary2015; Alexander, Reference Alexander2022). It seems that the research results are mixed. For example, a study of seaweed culture has shown that over half of the investment and operating expenditure is spent in local markets (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Kimpara and Valenti2021). It has also been argued that in Taiwan the Bluefin Tuna Cultural Festival – directly linked to the fishery – has increased economic prosperity (Lin and Bestor, Reference Lin and Bestor2020). However, in Canada, it has been shown that community and regional economic benefits are not automatically derived from simple quota allocations, but instead depend on a variety of factors (Foley et al., Reference Foley, Okyere and Mather2018). Furthermore, while the seafood sector has been viewed as a vehicle to alleviate poverty (Crona et al., Reference Crona, Van Holt, Petersson, Daw and Buchary2015; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Belton, Little and Islam2019), small-scale fisheries are often one of the poorest and most vulnerable groups worldwide (Apine et al., Reference Apine, Turner, Rodwell and Bhatta2019) and there is little evidence of how much of an effect the industry has. Some studies, however, have suggested a change to poverty level by those working in the sector (e.g. Glaser and Diele, Reference Glaser and Diele2004; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Belton, Little and Islam2019).

Improved infrastructure and access

Human-constructed infrastructure that supports society is the least explored area of seafood social sustainability. The need for basic local services such as schools, medical facilities, public transport and affordable housing is frequently noted (e.g. Symes and Phillipson, Reference Symes and Phillipson2009; Apine et al., Reference Apine, Turner, Rodwell and Bhatta2019; Larson et al., Reference Larson, Stoeckl, Fachry, Dalvi Mustafa, Lapong, Purnomo, Rimmer and Paul2021). However, there is little evidence to suggest that the seafood sector supports such things – at least in the peer-reviewed literature – although a study of the benefits of seaweed farming to wellbeing in Indonesia suggested that there had been improvements to housing and health (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Stoeckl, Fachry, Dalvi Mustafa, Lapong, Purnomo, Rimmer and Paul2021). In the grey literature, an assessment of the benefits of aquaculture to Scotland (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Gatward, Parker, Black, Boardman, Potts and Thompson2014), for example, found that the aquaculture industry did directly support housing and internet infrastructure, amongst other things. However, unless the infrastructure is paid for directly by the sector, it is difficult to assess the role that the sector has played in any changes to infrastructure.

Integrating social sustainability into existing industry and governance processes

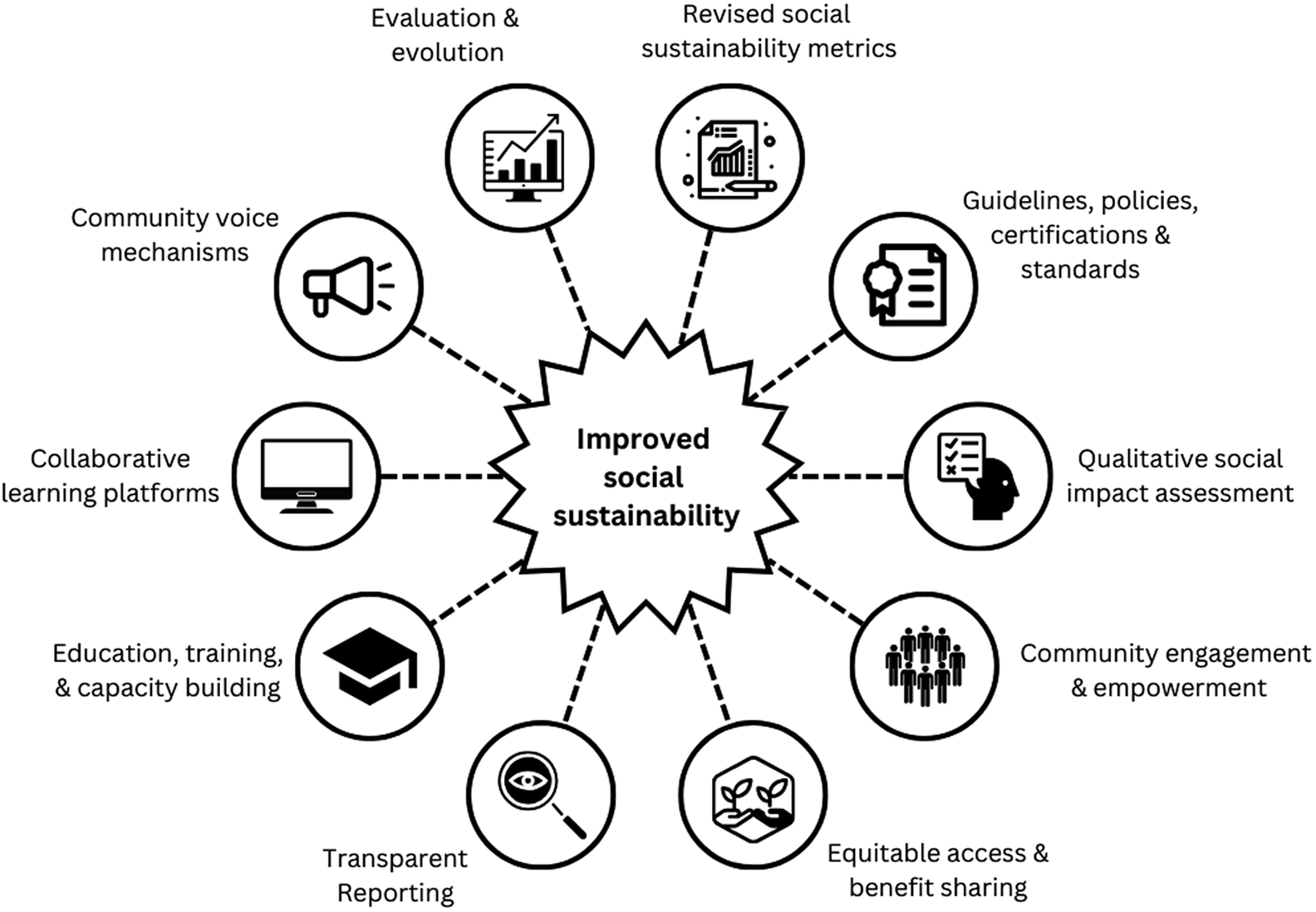

Existing industry and governance processes could be strengthened and enhanced in several ways (Figure 1). This may include incorporating social sustainability metrics and indicators that capture relational and subjective aspects into planning and monitoring frameworks, particularly co-created measures that relate to community wellbeing, social equity and inclusivity. Current social impact assessments can be constrained by quantitative measures, integrating qualitative aspects such as community empowerment and capacity building efforts would enable full participation of all relevant stakeholders. Indeed, ongoing dialogue between industry stakeholders, government bodies and communities of interest/place should be established to foster meaningful engagement and ensure social considerations are embedded in decision-making at every level. Mechanisms established for community participation and the inclusion of local voices could include community advisory panels, promoting community-based management approaches and fostering partnerships between industry and local stakeholders. Community engagement protocols should be co-developed. Responsible business practices, procurement guidelines and standards could include initiatives that enhance the overall quality of life at value chain ‘touch points’, with standards and certifications that explicitly include social criteria that address the breadth of social sustainability. Transparent reporting on social sustainability practices will lead to change, including mandatory requirements for companies to disclose their social impact, community engagement initiatives and adherence to social sustainability criteria. Using digital platforms can help with that reporting while learning platforms can facilitate knowledge exchange and collaboration to enhance transparency and accountability. Finally, regular evaluation of initiatives to assess effectiveness and best practice will enable adaptation to evolving social and environmental contexts.

Figure 1. Mechanisms by which to incorporate social sustainability into governance and industry processes.

Conclusion

The incorporation of social equity concerns into sector management is required to ensure human security amidst ongoing global challenges (Gollan et al., Reference Gollan, Voyer, Jordan and Barclay2019). Seafood policy that also considers economic and social sustainability in addition to environmental will increase the likelihood of greater social acceptance of management policies and priorities (ibid.). It is clear, however, that several knowledge gaps remain. While there has been a clear focus on developing social sustainability indicators, this has focused on those aspects which are easily measurable such as numbers of jobs and demographics. Approaches to identify and determine the effects of the more relational and subjective aspects of social sustainability (see e.g. Fudge et al., Reference Fudge, Ogier and Alexander2023) remain unclear. Some thematic areas of social sustainability also remain underdeveloped including fairness and equity in resource sharing and benefits, flow-on benefits for local communities and the role that the seafood sector plays in infrastructure and access to services. Moreover, the concept of the right to food as a human right was not explicitly mentioned in the literature (nor is it often considered within the legislation – e.g. UK Human Rights Act 1998), but this could be an area worth further consideration. A truly sustainable seafood product must account for tenable ecological and human wellbeing. If not, institutionalised inequality and compromised food, resource and livelihood security are just some of the outcomes – a state in which, it could be argued, we find ourselves today. There is an acute need to address the knowledge gaps identified above and incorporate what we already know about social sustainability into existing industry and governance processes. Without doing this, it will be impossible to meet the Sustainable Development Goals, in particular targets relating to zero hunger and sustainable food systems (T2.4); equal and safe employment (T8.5, T8.8); reduced inequalities (T10.2, T10.4); sustainable management of natural resources (T12.2, T12.6, T12.8) and transparent and participatory decision-making (T16.6, T16.7). To not do this may mean moving the dial even closer towards environmental and societal collapse.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.31.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: K.A.A.; Data curation: K.A.A. and I.K.; Formal analysis: K.A.A. and I.K.; Writing – original draft: K.A.A. and I.K.; Writing – review & editing: K.A.A. and I.K.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Editor

Thank you for your invitation to write a commissioned review article for the journal on the topic of the sustainability of seafood systems. Please find enclosed a review article titled ‘Social sustainability in seafood systems’ by myself and my colleague Dr Ingrid Kelling. In this article, we argue that despite an increasing emphasis on the sustainable development discourse, there is much uncertainty regarding what social sustainability means and how it can be applied. This has meant that, like other industries, the seafood sector has been criticized for neglecting social issues. In this review, we provide a broad overview of the current state of knowledge relating to social sustainability in the seafood sector (comprising fisheries and marine aquaculture). We also identify where research gaps remain. We anticipate that this will inform those undertaking research in this field and assist those working in the sector to focus their efforts. We hope that this will be of interest to you and to your readers.

Kind regards

Karen Alexander