5.1 Introduction

There is increasing recognition that fossil fuel subsidy reform (FFSR) can contribute to a host of environmental, social, and economic objectives, and thereby contribute to achieving both the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change (e.g. Jakob et al. Reference Jakob, Chen, Fuss, Marxen and Edenhofer2015; Jewell et al. Reference Jewell, McCollum, Emmerling, Bertram, Gernaat, Krey, Paroussos, Berger, Fragkiadakis, Keppo, Saadi, Tavoni, van Vuuren, Vinichenko and Riahi2018; UNEP 2018). However, at several hundred billion dollars a year (OECD 2018), fossil fuel subsidies persist in both developed and developing economies.

While past research has sought to address this puzzle through the lens of domestic politics – pointing to challenges to reform such as popular opposition, vested interests, interest groups, path dependency, and capacity and data gaps (e.g. Victor Reference Victor2009; Inchauste and Victor Reference Inchauste and Victor2017) – international cooperation can also play an important role in promoting, or impeding, FFSR (Smith and Urpelainen Reference Smith and Urpelainen2017; Skovgaard and van Asselt Reference Skovgaard, van Asselt, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). For instance, while international institutions can adopt new rules, catalyze international commitments, enhance states’ accountability, and facilitate information-sharing and capacity-building, there is also a risk that they will struggle to move beyond rhetoric, promote weak, vague, or otherwise inadequate norms, or be perceived to favour certain approaches over others. Where more than one international institution is active at the same time, the door is open for cooperation, as well as competition and conflict between different institutions. This raises questions regarding the institutional coherence of international FFSR governance (see also Chapter 2).

In this chapter, we consider how various international institutions are approaching FFSR governance. First, we briefly introduce the rationale for FFSR (Section 5.2). Next, we discuss the international FFSR governance architecture, with a view to analyzing institutional coherence at the meso level (Section 5.3). This includes the possible emergence of a core norm of FFSR, membership distribution, and the governance functions carried out by the various international institutions active in this area. To further evaluate the degree of coherence in this field, we zoom in on the meso level. Concretely, we examine a subset of three international clubs whose FFSR activities are among the most prominent globally: the Group of 20 (G20), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform. We first introduce the FFSR activities being undertaken by each of these three institutions, and then consider the interlinkages between these activities, as well as efforts to manage them (Sections 5.4–5.5). We conclude by considering implications of our findings for the future management of FFSR governance and the complexity thereof (Section 5.6).

5.2 Fossil Fuel Subsidies: The Rationales for Reform

Fossil fuel subsidies are a form of government support that benefits the producers or consumers of coal, oil, and gas. Both developed and developing countries subsidize fossil fuels: subsidies for consumers are more commonplace in developing countries, while those for producers are found across the board (Bast et al. Reference Bast, Doukas, Pickard, van der Burg and Whitley2015). Such assistance can come in many guises; some more direct than others. Common types of subsidies include direct transfers of funds; the setting of prices above or below market rates; exceptions or reductions on taxes; favourable loans, loan guarantees, or insurance rates; and preferential government procurement. Support can also be provided in-kind, such as when a government builds infrastructure for the primary or exclusive use of a coal company.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have all published estimates of government support to fossil fuel use and consumption. These numbers vary, depending on what valuation method is used; which countries and regions are covered; fluctuations over time; and which definition of a ‘subsidy’ is being used. However, even by the more conservative OECD and IEA estimates, global fossil fuel subsidies totalled between US $373 and 617 billion per year between 2012 and 2015 (OECD 2018). The IMF’s approach, which incorporates the non-priced externalities of fossil fuel production and consumption such as air pollution, traffic congestion, and climate change, suggests the public costs lie much higher: in the range of US $5.3 trillion in 2015 (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2017).

Unsurprisingly, the IMF’s broad ‘post-tax’ interpretation of what constitutes a fossil fuel subsidy has proved controversial. Yet the Fund’s approach does help to illustrate the broader societal costs of fossil fuels. Moreover, regardless of the definition used, fossil fuel subsidies are associated with significant economic, social, and environmental impacts. Even excluding non-priced externalities, fossil fuel subsidies can represent a major burden on the public purse, taking up as much as 35 per cent of the public budget in some countries (El-Katiri and Fattouh Reference El-Katiri and Fattouh2015). They thereby reduce the investments available for key development sectors such as health and education (Merrill and Chung Reference Merrill and Chung2015), representing an important opportunity cost for developing countries in particular. Moreover, while fossil fuel subsidies are often defended as being ‘pro-poor’, the evidence suggests that such measures tend to be highly regressive, and, perversely, generally benefit those who consume the most energy in society, or powerful interest groups (Arze del Granado and Coady Reference Arze del Granado and Coady2012).

But perhaps the most urgent rationale for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies lies in their environmental impact. These subsidies artificially enhance the competitiveness of fossil fuels, potentially locking in unsustainable fossil fuel infrastructure for decades (Asmelash Reference Asmelash2016). Indeed, it has been estimated that more than a third of carbon emissions between 1980 and 2010 were driven by fossil fuel subsidies (Stefanski Reference Stefanski2014). According to the 2018 Emissions Gap Report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), phasing out fossil fuel subsidies worldwide could reduce global carbon emissions by up to 10 per cent (UNEP 2018). Government support to fossil fuels also diverts investment from areas such as energy efficiency and renewable energy, while their reinvestment in these areas could bring about important climate change mitigation benefits (Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Toft Christensen and Sanchez2016).

Notwithstanding the adverse fiscal, socioeconomic, and environmental effects of fossil fuel subsidies, decades of experience with fossil fuel subsidy reform in various countries attest to the political challenges. While some countries, such as India, Indonesia, and Mexico, have made some progress in reforming subsidies, other countries, such as Nigeria, have struggled to implement or sustain reforms. Reforms have usually been linked to macro-economic factors such as falling fossil fuel prices (Benes et al. Reference Benes, Cheon, Urpelainen and Yang2015) or financial crises, but in many cases domestic political factors, such as the role of special interest groups, a country’s institutional and governance capacity, and the political system, play a crucial role in making FFSR a success (Skovgaard and van Asselt Reference Skovgaard, van Asselt, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

The importance of macro-economic and domestic political factors in hindering or driving FFSR may suggest that there is no or only a limited role for international cooperation in steering reform. However, as the next section shows, international governance can help drive (or hinder) domestic reform.

5.3 Meso-Level Coherence

5.3.1 Emergence of the FFSR Institutional Complex

As fiscal instruments of energy policy that can have numerous social, economic, and environmental effects, it is not surprising that fossil fuel subsidies are governed by a range of institutions from respective domains, such as energy, trade, and sustainable development (Van de Graaf and van Asselt Reference Van de Graaf and van Asselt2017). However, until well into the previous decade, there were hardly any international institutions focusing specifically on the problems posed by fossil fuel subsidies, or options for their reform.

This changed in 2009, a watershed moment for the international politics of FFSR. Meeting in Pittsburgh in September, G20 leaders made the first international commitment to address fossil fuel subsidies (G20 2009). This commitment was closely followed by a similar pledge by the 21 APEC economies (APEC 2009). Then-US President Barack Obama is widely credited with orchestrating the G20 pledge as he sought to shape his administration’s climate legacy, with the economic crisis offering a further window of opportunity to promote new approaches to financial governance (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

Over the subsequent decade, a range of additional institutions has become active in this field. These include various international organizations such as the OECD, IEA, IMF, and World Bank; additional minilateral coalitions such as the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (Friends); and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Global Subsidies Initiative. The profile of FFSR has further been raised through two further developments: a reference to the need to ‘rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ in SDG target 12.c (UN 2015); and the recent adoption, by twelve members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), of a Ministerial Statement that highlights the need to take this agenda forward in the international trade sphere (IISD 2017).

5.3.2 The Core Norm of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

The starting point of any analysis of a core norm of FFSR is the aforementioned G20 commitment, made at the Group’s third leaders’ summit in Pittsburgh in September 2009. In their statement, leaders recognized that inefficient fossil fuel subsidies encourage wasteful consumption, distort markets, impede investment in clean energy sources, and undermine efforts to deal with the threat of climate change (G20 2009, preamble). As such, they committed to ‘[r]ationalize and phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption’ (G20 2009, paragraph 29). As mentioned in Section 5.3.1, ministers of APEC adopted a similar pledge later that year (APEC 2009).

While we take this formulation as the general core norm for this chapter, the precise content of the norm of FFSR remains contested and invites different interpretations. First, as mentioned in Section 5.2, there is no universal definition of a ‘fossil fuel subsidy’, and indeed, different organizations have historically approached this question in various ways (see also Chapter 8). It should be mentioned, however, that a common conception of a fossil fuel subsidy may be increasingly within reach, in particular as official guidance for their measurement has been released in the context of the SDG process (UNEP et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the G20 and APEC commitments leave important qualifiers such as ‘inefficient’ and ‘wasteful consumption’ undefined. This has given countries considerable leeway to adopt their own interpretations of their international FFSR commitments (Asmelash Reference Asmelash2016; Aldy Reference Aldy2017). As a consequence, countries such as Japan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom have been able to claim they have no fossil fuel subsidies at all (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). Another issue that remains unclear is by when fossil fuel subsidies need to be phased out. Although a range of stakeholders, including leading investors and insurers (Reuters Reference Reuters2017), have called for a phase-out by 2020, and the G7 adopted a date of 2025, the G20 and APEC commitments do not have a clear timeline (with the G20’s reference to the ‘medium-term’ adding limited guidance).

Despite the textual ambiguity of these initial pledges, the understanding that at least a subset of fossil fuel subsidies ought to be reformed has gained significant global traction over the past decade, including through a reference to FFSR in the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015, SDG target 12.c). The European Union has also adopted its own pledge to phase out harmful fossil fuel subsidies by 2020. Indeed, as noted by Rive (Reference Rive, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018, 164), the G20 and APEC’s initial pledges have been instrumental in ‘a reframing of a conception of fossil fuel subsidies as a legitimate government tool to enhance economic development, energy security and welfare into a normative conception that is broadly negative in fiscal and environmental terms’.

Recent developments nevertheless suggest that support for this core norm cannot necessarily be taken for granted. In 2017, the year US President Trump assumed office, G20 leaders omitted FFSR from their declaration for the first time since 2009. While the accompanying G20 Hamburg Climate and Energy Action Plan for Growth (G20 2017) includes a separate FFSR section, the document contains an overall reservation from the United States. Significantly, the 2017 APEC Leader’s Declaration also omits a reference to FFSR (APEC 2017).

5.3.3 Membership

The international institutions governing fossil fuel subsidies include government-driven multilateral regimes, international organizations, and clubs involving a small group of countries (see Table 5.1). This diversity notwithstanding, all but one of the institutions outlined in Table 5.1 are public. The only exception is the Geneva-based Global Subsidies Initiative, a programme of the International Institute for Sustainable Development, a Canadian NGO (Lemphers et al. Reference Lemphers, Bernstein, Hoffman, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). One explanation for this is that fossil fuel subsidies are, by definition, provided by governments, who therefore have a key role in addressing them. The dominant role of public institutions suggests that the global governance architecture on FFSR is somewhat less institutionally complex than that of other subfields in the climate-energy nexus that heavily involve civil society and the private sector (see Chapter 3).

Table 5.1 Overview of governance functions across different types of institutions (public, hybrid, private) for fossil fuel subsidy reform.

| Public | Hybrid | Private | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standards & Commitments | G7, UNFCCC, UN (SDGs) | ||

| Operational | |||

| Information & Networking | IEA, OECD, OPEC, WTO, UNEP | ||

| Financing | |||

| Standards & Commitments; Operational | |||

| Operational; Information & Networking | Global Subsidies Initiative | ||

| Information & Networking; Financing | IMF, World Bank | ||

| Standards & Commitments; Information & Networking | APEC, Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform, G20 | ||

| Standards & Commitments; Financing | |||

| Operational; Financing | |||

5.3.4 Governance Functions

The range of international institutions working on FFSR covers the full gamut of governance functions. The diversity of these institutions engaged is notable: they range from those whose core mandates concern fiscal governance (e.g. the G20, OECD, IMF, and World Bank), to trade liberalization (WTO and APEC), to energy (IEA and OPEC), to the environment and climate change (UNEP and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)).

In terms of standards and commitments, forums such as the G20, G7, APEC, and Friends have made pledges or otherwise publicly promoted the norm of FFSR. The UN’s 2030 Agenda, through SDG 12.c., also encourages countries to ‘rationalize’ inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. Fossil fuel subsidy review processes, such as those organized by the G20 and APEC, provide an opportunity for individual countries to pledge to address certain subsidies; while the UNFCCC, through its system of nationally determined contributions (NDCs), allows countries to make similar national commitments.

Regarding information and networking, organizations such as the OECD, IEA, IMF, World Bank, Friends, and Global Subsidies Initiative conduct research to clarify the scale of subsidies provided. At the same time, forums such as the G20, APEC, and the WTO create mechanisms for countries to report on their fossil fuel subsidies, although notification rates are patchy. The UN Environment Programme supports countries in better understanding the extent of their fossil fuel subsidies through the development of international indicators. As discussed in more detail in Section 5.4, the Friends engage in behind-the-scenes networking to further promote international reform efforts.

Operational activities such as technical assistance and capacity-building are provided by international organizations such as the World Bank, Friends, and Global Subsidies Initiative, including through publications, events, and online webinars.

Finally, organizations such as the World Bank and Friends have made financing available to help developing countries undertake reform, while structural adjustment policies implemented by the IMF and the World Bank have at times involved FFSR.

5.3.5 Summary: Coherence at the Meso Level

The coherence of the institutional complex for fossil fuel subsidies may seem limited at first sight. There is not a single definition that all institutions adhere to and, as Section 5.2 pointed out, existing definitions and ways of measuring subsidies differ widely. Moreover, international institutions seem to address fossil fuel subsidies for very different reasons, from fiscal to environmental. Lastly, membership is heavily skewed toward public institutions, and the role of private and hybrid institutions is limited.

However, the level of inconsistency should not be exaggerated. First, notwithstanding divergences in the way fossil fuel subsidies are defined and measured, there are also important similarities in the various definitions published by the OECD, IEA, and IMF (Koplow Reference Koplow, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018), and joint estimates by the OECD and IEA have been published (OECD 2018). Second, a deeper dive into the types of governance functions fulfilled by various institutions suggests that there is a certain synergy emerging, with all governance functions being fulfilled by several institutions (Table 5.1). While some forums have been instrumental in agenda-setting, and the formulation of broad commitments (e.g. the G20, APEC, Friends), other organizations have focused on providing information on subsidies and their impacts (e.g. the OECD, IEA, IMF), while yet others have been key in supporting FFSR on the ground through, for instance, financing and capacity-building (e.g. World Bank, Global Subsidies Initiative).

Partially, this distribution is the result of active coordination. As a notable example, the G20’s 2009 commitment to phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies largely preceded the availability of robust data into global and domestic fossil fuel subsidies (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). However, in their Pittsburgh Statement, G20 leaders requested ‘relevant institutions’, such as the IEA, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the OECD, and the World Bank (the ‘IGO-4’), to provide an analysis of the scope of energy subsidies and suggestions for the implementation of the G20’s reform efforts (G20 2009), with several reports issued thus far, including on how such reforms can be made while assisting the poor (IEA, OECD, and World Bank 2010a, 2010b, 2011; World Bank 2014).

In terms of the terminology introduced in Chapter 2, our overall assessment of the meso-level coherence therefore falls between synergy and division of labour.

5.4 Micro-Level Coherence

The remainder of this chapter will focus on three forums in particular to scrutinize coherence at the micro level of the FFSR subfield. These forums are: the G20, APEC, and Friends. Despite differing overarching mandates and approaches, they have been among the most active in this subfield, including through proactive promotion of an international norm on FFSR. All three are clubs involving a limited number of economies, who moreover began to address fossil fuel subsidies roughly around the same time (2009–2010). As such, their activities in this space are comparable. Nevertheless, as will be discussed, there are differences in their approaches as well. To shed light on how international FFSR governance is impacted by the parallel efforts of these three forums, we consider how each is addressing FFSR, to what extent their approaches are consistent, and the management of the interaction between them.

5.4.1 Institutions under Scrutiny

5.4.1.1 The Group of 20

The Group of 20 was established in 1999 in response to the Asian financial crisis. During the financial crisis of 2008, the Group’s status was elevated to that of a leaders’ summit, with members’ heads of state and government convening once or twice a year since to address issues relating to global economic governance and reform (Wade Reference Wade2011). Comprising nineteen of the world’s largest developed and developing economies,Footnote 1 as well as the European Union, the Group accounts for some two-thirds of global population; 85 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP) (Kim and Chung Reference Kim and Chung2012), and 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions (Climate Transparency 2015).

While economic governance is the Group’s raison d’être, climate change has featured on the leaders’ agenda from the beginning (Kirton and Kokotsis Reference Kirton and Kokotsis2015). Assessments of its performance in this regard have often been cautiously positive (Van de Graaf and Westphal Reference Van de Graaf and Westphal2011; Garnaut Reference Garnaut2014; Kirton and Kokotsis Reference Kirton and Kokotsis2015), with commentators identifying the Group’s flexibility over topics and time; its ability to exploit issue linkages; and ‘a sense of being equal’ among members (Kim and Chung Reference Kim and Chung2012) as advantages. However, important drawbacks of the ‘exclusive minilateralism’ pursued by the G20 have also been identified, including a lack of legitimacy, transparency, and accountability, in particular when compared to bodies with a more universal membership, such as the UNFCCC (Eckersley Reference Eckersley2012; Kim and Chung Reference Kim and Chung2012).

As mentioned earlier, the G20’s 2009 FFSR pledge has been instrumental in elevating the issue to the international agenda. In addition to this role, leaders at the 2009 Pittsburgh summit also agreed to prepare and report on implementation strategies and time frames for the rationalization and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies (G20 2009). To facilitate this work, the G20 established a working group on energy in which energy experts, under supervision of Finance and Energy ministers, reviewed the fossil fuel subsidies in their countries (Kim and Chung Reference Kim and Chung2012). However, despite its potential to enhance transparency in the area of fossil fuel subsidies, the results of this exercise have been described as ‘meagre’ (Van de Graaf and Westphal Reference Van de Graaf and Westphal2011, 28) and ‘disappointing’ (de Jong and Wouters Reference de Jong, Wouters and Talus2014, 34), with almost half of the G20 countries providing little or no further information on their subsidies (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

A more in-depth process to increase the transparency on subsidies of a subset of G20 countries is currently ongoing. This goes back to June 2012, when G20 Leaders requested Finance ministers to explore options for a voluntary peer review (VPR) process (G20 2012). In February of the following year, G20 Finance Ministers committed to undertake such a process, and, several months later, released a corresponding methodology (G20 Energy Sustainability Working Group 2013). Reciprocal VPRs have been conducted by China and the United States, as well as Germany and Mexico. Reviews between Indonesia and Italy, and Argentina and Canada, have also been announced. While the VPR process appears to provide opportunities for domestic and bilateral learning in the area of FFSR,Footnote 2 engagement in the voluntary process does not necessarily guarantee enhanced transparency. Germany’s VPR in particular has been accused of ‘ignoring the majority of fossil fuel subsidies’ in the country (ODI 2017).

5.4.1.2 The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation was created in 1989 as a regional forum in response to the increasing economic interdependence of the region (Elek Reference Elek2005). Consisting of twenty-one developed and developing countries in the Asia-Pacific region, APEC countries account for half of global trade, 60 per cent of world GDP (APEC 2018), and 60 per cent of global energy demand (IEA 2017). Consequently, energy policy developments within APEC have significant impacts on global energy trends (IEA 2017).

Although action on climate change and energy has not been a central focus of APEC’s activities, since 2009 the forum has engaged in a range of activities related to FFSR. Just weeks after the G20’s 2009 commitment in Pittsburgh, APEC leaders similarly pledged to ‘rationalise and phase out over the medium term fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption’, while ‘recognising the importance of providing those in need with essential energy services’ (APEC 2009).Footnote 3 As with the G20, enhancing transparency of existing subsidies was a first step in this effort. Meeting in Japan in 2010, APEC Energy Ministers instructed the group’s Energy Working Group (EWG) to provide an initial assessment of fossil fuel subsidies in the region (APEC Energy Ministers 2010). In 2011, APEC Leaders meeting in Honolulu agreed to set up a ‘voluntary reporting mechanism’ that allows members to self-report progress toward reform (APEC 2011).

Building on their peer review experiences in the areas of renewable energy and energy efficiency,Footnote 4 APEC economies have also engaged in their own VPR process for fossil fuel subsidies.Footnote 5 Guidelines for VPRs were adopted in November 2013 (APEC EWG 2013), with Peru as the first APEC economy to undergo review.Footnote 6 Additional VPRs have been conducted for New Zealand (2015), the Philippines (2015), Chinese Taipei (2016), and Vietnam (IEA 2017). The APEC VPR process reviews fossil fuel subsidies in the volunteer economy, facilitated by the EWG and FFSR Secretariat, which was established to assist developing economies through coordination of peer review activities and provision of technical and logistical support.Footnote 7 The results of the reviews, including policy reform recommendations, are shared to help disseminate lessons learned and best strategies for reform (IEA 2017).

Compared to the G20, APEC includes more developing countries.Footnote 8 Perhaps reflecting this more diverse membership, capacity-building has also been an important focus of APEC’s FFSR work (APEC 2013), with dedicated FFSR capacity-building workshops held in Honolulu (APEC EWG 2015) and Jakarta (APEC EWG 2017).

5.4.1.3 The Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

The Friends is an informal coalition of countries set up in June 2010 ‘to build political consensus on the importance of fossil fuel subsidy reform’ (GSI n.d.). Currently comprising nine states – Costa Rica, Denmark, Ethiopia, Finland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Uruguay – the group’s establishment was directly inspired by the G20’s 2009 commitment to phase out fossil fuel subsidies (Rive Reference Rive2016). Indeed, the Friends explicitly identifies itself in relation to, and in contrast with, the G20: as ‘an informal group of non-G20 countries’ (Friends, n.d.).Footnote 9 Informal coalitions of ‘Friends’ that bring together countries with similar views around particular issue areas have become a familiar phenomenon in international affairs, including in the areas of trade, development, environment, and disarmament (Rive Reference Rive, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). The Friends has elicited comparisons with the ‘Friends of Fish’: a group of developed and developing countries working within the WTO to promote sustainable fishing practices and elimination of harmful fishing subsidies (Young Reference Young2017).

The Friends was established by New Zealand, which continues to play a leading role (Rive Reference Rive2016). The Global Subsidies Initiative performs a support function for the group (Lemphers et al. Reference Lemphers, Bernstein, Hoffman, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). Coordination takes place at the sidelines of biannual meetings of the OECD Joint Working Party on Trade and Environment and other international meetings, through issue-specific meetings of technical experts, and through monthly conference calls.Footnote 10

The Friends has primarily engaged in ‘soft’ activities in its efforts to promote FFSR. This is in line with Rive’s (Reference Rive, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018, 158) observation that ‘the effectiveness of Friends groups on international norm and policy development and negotiations largely does not depend on securing and wielding political “hard” power … [i]nstead, it depends on their ability to network, influence, innovate, problem solve and profile raise’.

In this regard, one key forum that the Friends has focused on is the WTO. Through informal lobbying efforts as well as public outreach activities spearheaded by New Zealand, the group has been instrumental in the adoption, at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference, of a Ministerial Statement on fossil fuel subsidies. In the statement, twelve signatories urge the WTO to advance the discussion on fossil fuel subsidies, and request transparency and reform of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption. Such engagement has the potential to make a significant dent in fossil fuel subsidies globally, given the WTO’s previous experience with subsidies reform, for instance in the area of agriculture (Verkuijl et al. Reference Verkuijl, van Asselt, Moerenhout, Casier and Wooders2019). Besides the international trade space, the Friends have also promoted FFSR within the UNFCCC process, advocating, among others, the inclusion of reform plans by countries in their NDCs (Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Toft Christensen and Sanchez2016).

Part of the Friends’ approach also appears to lean on ‘leading by example’, with three Friends’ Members having undergone self- or peer reviews of their fossil fuel subsidies (Finland and Sweden have conducted independent reviews, while New Zealand’s was completed under the auspices of APEC). However, it is worth noting that while at least thirteen countries have made reference to fossil fuel subsidies in their NDCs to date, this includes only two Friends countries: Ethiopia and Costa Rica (Terton et al. Reference Terton, Gass, Merrill, Wagner and Meyer2015; Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Toft Christensen and Sanchez2016).

Another key output of the Friends was the release of a Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform Communiqué in April 2015, which invites all countries, companies, and civil society organizations to join in supporting accelerated action to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies (Friends 2015). Although it remains to be seen to what extent endorsement will lead to meaningful stakeholder engagement, the document has broadened the range of actors overtly committed to the cause of FFSR. These now include twenty-eight non-G20/APEC countries as well as a host of international organizations and NGOs, and associations representing more than 90,000 investors and corporations (IISD 2016; Rive Reference Rive, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

Since the group’s inception, developed country Friends members have also contributed to reform efforts through financial support to the FFSR-related activities of organizations such as the World Bank, IMF, OECD, and the Global Subsidies InitiativeFootnote 11 (see Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Toft Christensen and Sanchez2016). Finally, the Friends also contribute to capacity-building through side events at international meetings and webinars on FFSR (Friends 2018).Footnote 12

5.4.2 Interlinkages

The activities of the G20, APEC, and Friends intersect in various ways, even as the three groups show variations in terms of membership and geographic scope, the norms they promote, and their governance functions. Taking these dimensions as a starting point, this section examines the coherence between the three groups and their FFSR activities.

There appears to be general consistency with respect to the core norm that the G20, APEC, and Friends espouse in relation to FFSR. In their respective Leaders’ Declarations, both the G20 and APEC explicitly commit to ‘rationalise and phase out’ fossil fuel subsidies that are ‘inefficient’. The G20 further qualifies its reform commitment by singling out subsidies that ‘encourage wasteful consumption’. On the other hand, the Group’s pledge is strengthened by the inclusion of a ‘medium-term’ timeline for reform. Although APEC’s initial pledge in 2009 contained an identical reference, this was dropped in some of the later iterations (e.g. APEC 2010, 2011, 2012). The Friends’ efforts in this area appear geared to ‘help remind countries’ to keep this topic on their agendas through various diplomatic channels.Footnote 13 Notably, however, the norm espoused in the Friends’ 2015 Communiqué does not meaningfully depart from those of other previous pledges.Footnote 14 Similar to the G20 and APEC commitments, the document omits a reference to a specific date for achievement of FFSR and leaves the concept of a subsidy undefined.

As noted, the textual ambiguity of the G20 and APEC’s pledges has enabled several economies in these groups to avoid taking any meaningful action on FFSR. While it is unsurprising that certain group members – particularly those with large subsidies or a big fossil fuel industry – may seek to maintain the opacity of the FFSR norm, it is less evident why a group such as the Friends has not succeeded in further crystallizing it. One explanation may lie in the fact that the Friends has trod a fine line between trying to enhance ambition while simultaneously seeking not to ‘alienate’ other governments,Footnote 15 particularly those from the G20 and APEC.Footnote 16 Another reason relates to a possible strategic value in maintaining the ambiguity of the term ‘subsidy’. A flexible definition can be conducive to reform as it enables governments to engage at a level they feel comfortable with, rather than setting ‘too high a threshold’ for action.Footnote 17

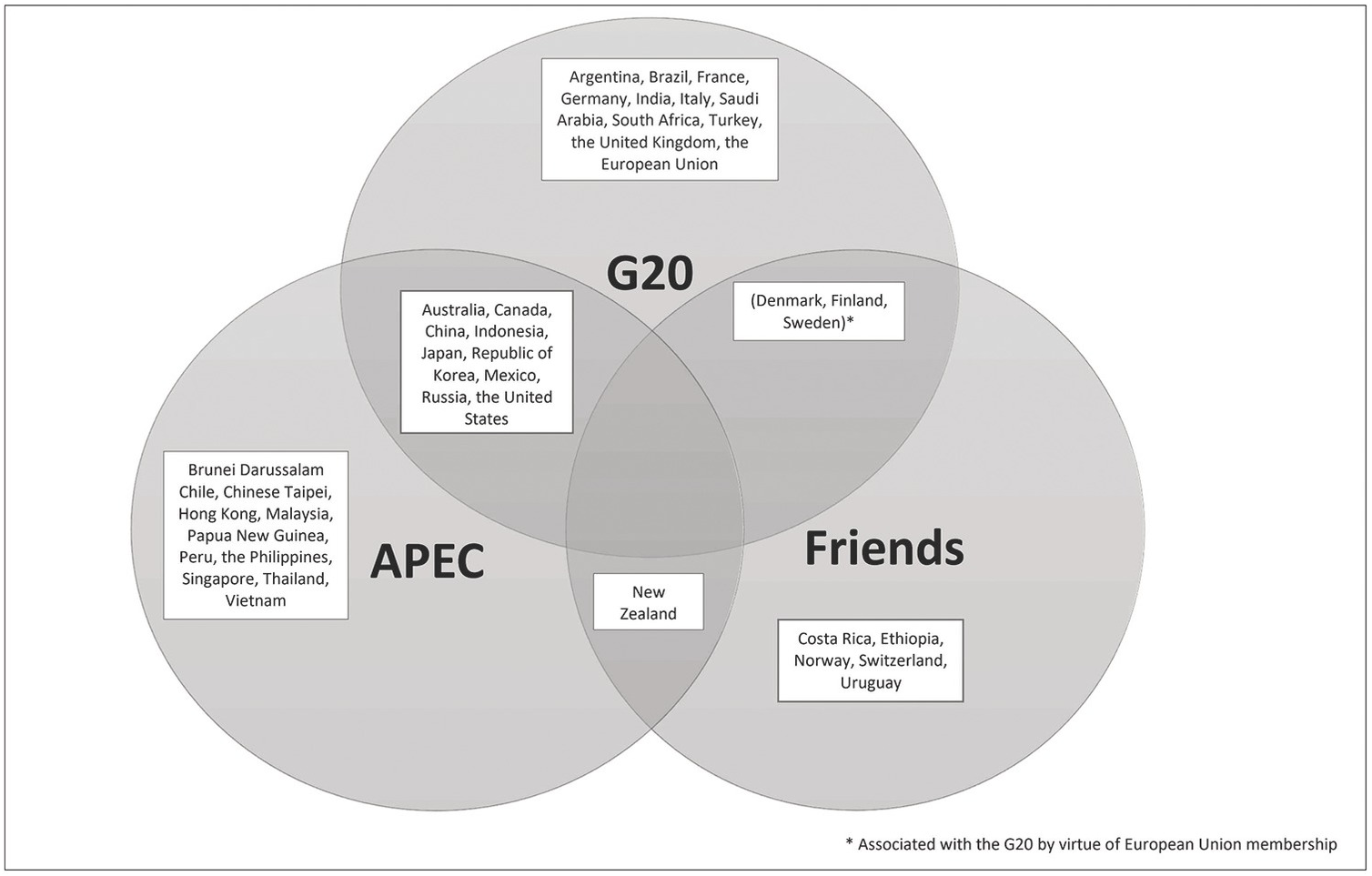

As regards membership, Figure 5.1 illustrates the degree of overlap between members of the G20, APEC, and Friends. As shown, the majority of G20, APEC, and Friends economies (28 out of 41) only belong to one of these three groups. However, all three groups display at least some degree of overlapping membership, with thirteen members associated with two of the groups. Since countries are unlikely to pursue duplicative or contradictory policies in different forums with similar goals, we can hypothesize that such overlaps will lead to more coherent governance. We can further expect coherence to be enhanced where membership overlaps strongly and where pivotal actors with the ability to influence dynamics straddle multiple groups (Gehring and Faude Reference Gehring and Faude2014).

Figure 5.1 Membership of the G20, APEC, and Friends.

Against this backdrop, it is notable that nine economies are a member of both the G20 and APEC. Moreover, two key global players – the United States and China – have been advocates of FFSR across both groups,Footnote 18 including by engaging in some of the first peer reviews, and, in the case of the United States, giving impetus to the initial FFSR pledges made in these forums. Yet, although these interlinkages may increase the likelihood of a common approach between both groups, important differences between the G20 and APEC remain in terms of both their membership and mandate. As such, the mere existence of the G20’s 2009 FFSR pledge did not make such a commitment a fait accompli in APEC: APEC economies’ own interest in fiscal reform at the time was the decisive factor.Footnote 19

Beyond G20-APEC overlaps, New Zealand’s membership of both APEC and the Friends also stands out. As one of the strongest proponents of FFSR in APEC, the country has been ‘keen to lead by example’ in the group, for instance by being among the first to undergo peer review and by seeking to set a ‘good benchmark’ in doing so.Footnote 20 Seeing their APEC activities as ‘part of their Friends work’, the country has moreover sought to work with like-minded APEC members to inspire APEC to take up similar commitments to the G20.Footnote 21 As with China and the United States’ overlapping memberships, it is likely that New Zealand’s membership of both groups has strengthened the consistency and complementarity between the Friends and APEC’s approaches, including by allowing other APEC members to draw on New Zealand’s expertise in this area.Footnote 22 By contrast, there is little evidence that G20 dynamics have been affected by Denmark, Finland, and Sweden’s association with both the Friends and – by virtue of their European Union membership – the G20: presumably a result of competing visions on the topic of reform among the Union’s Member States.

While overlapping membership has thus helped to enhance consistency between the three groups, the fact that members diverge, particularly in terms of their geographic scope, also contributes to the complementarity of their actions. Indeed, by following on the G20’s FFSR pledge, APEC committed eleven additional non-G20 economies in the Asia-Pacific region to FFSR.Footnote 23 Similarly, the Friends’ 2015 Communiqué broadened support for FFSR to an additional twenty-eight countries and numerous other stakeholders. The three groups’ FFSR review activities have also been complementary in scope: at the time of writing, twelve economies had undergone, or committed to undertake, peer reviews under APEC and the G20, with an additional two Friends members having completed self-reviews.

Lastly, in terms of governance functions, there is a significant degree of overlap between the FFSR activities of the G20 and APEC, with both forums engaging in standard and commitment setting, as well as information and networking activities through their progress tracking and peer reviews. Compared to the G20, APEC appears to place a stronger emphasis on building the capacity of its members to engage in FFSR by facilitating operational activities such as capacity-building. Nevertheless, these differences should not be overstated. As observed by Steenblik,Footnote 24 peer review – while primarily related to information – can also be regarded as an important means of promoting capacity-building, allowing developing and developed countries alike to create a better understanding of the types of fossil fuel subsidies that exist, and ways of addressing them.

There are nonetheless nuances in the way the G20 and APEC have approached their activities. Although much of the G20’s FFSR work has been concentrated in its energy working group, its original pledge was coordinated by finance ministers, who have remained heavily involved in this topic.Footnote 25 APEC’s reform activities, on the other hand, have largely been restricted to the forum’s EWG and energy ministers: a deliberate choice on behalf of the forum’s FFSR proponents, who feared that involvement of senior finance officials would have rendered this work ‘too political’.Footnote 26 By allowing APEC to draw on its EWG’s experience in delivering on projects in other areas, including peer reviews on renewable energy and energy efficiency, this approach enabled APEC economies to complete the first fossil fuel subsidy review as early as July 2015. By contrast, the G20’s approach to peer reviews has been more political, including through the ‘pairing’ of a developed and developing country review in every review cycle, resulting in a more drawn-out process.Footnote 27

Both groups’ approaches to VPRs may be associated with certain advantages. By enabling individual countries to undergo peer review once they are ready, APEC’s approach has allowed for a quicker succession of reviews than the G20 approach, which is based on willing pairs of countries stepping forward. On the other hand, it is notable that all the G20 members of APEC have conducted their peer reviews under the auspices of the G20, which is perhaps associated in the public’s mind with greater political prestige.Footnote 28 One challenge for both groups is how to maintain momentum for VPRs going forward. Naturally, those countries most eager to undergo review were among the first to volunteer, while some remaining countries are more reluctant to engage: for example, several maintain they have no inefficient subsidies in the first place, or want to delay committing to a review for reasons of political timing.Footnote 29 Moreover, a backlog of peer reviews has reportedly accumulated under APEC, as funding for these efforts, which had previously come largely from the United States, has not been renewed.Footnote 30

The Friends’ activities have some overlaps with those of the G20 and APEC. Much like the G20 and APEC’s reform pledges, the Friends’ 2015 Communiqué focuses on setting standards and commitments for FFSR. Similarly, some members have engaged in information and networking by undergoing fossil fuel subsidy reviews. However, in line with the Friends’ consensus-building role, their activities have generally been more externally focused than those of the other two groups. While the G20 and APEC’s work largely revolves around their member base, the Friends have actively engaged in operational activities such as events and webinars to influence third actors, including G20 and APEC members, as well as those involved in forums such as the WTO and UNFCCC. Key achievements in this regard include socialization of the concept of peer review within the G20 and APEC,Footnote 31 and the adoption of the Ministerial Statement on FFSR at the WTO. Individual Friends members have also provided financing for FFSR through their aid budgets. By seeking to strengthen existing reform efforts and spread such efforts to new forums, the Friends’ activities seem to provide a useful complement to the G20 and APEC’s internal efforts.

5.4.3 Mechanisms

All three consistency mechanisms identified in Chapter 2 are reflected in the dynamics between the G20, APEC, and Friends.

Normative mechanisms, whereby the norms and rules of one institution impact on those of another, seem to be at play with regard to all three groups’ public FFSR announcements. After the G20 announced its FFSR commitment in September 2009, APEC quickly followed suit with an almost identical pledge to ‘rationalise and phase out’ such subsidies, while leaving important questions about the scope of these measures and end-date for their phase-out, unaddressed. Although the Friends’ Communiqué does not represent a direct commitment, the document similarly mirrors the key facets of the G20 and APEC pledges, even where those fall short on ambition and clarity. From a long-term perspective, there may be value in such a prudent approach, as ‘speaking the same language’ arguably allows for more possibilities for the Friends to engage with the other two groups, including their more hesitant members.

Cognitive mechanisms, whereby knowledge and information are shared across institutions, are similarly present across all three groups. Like many other organizations working on energy, the APEC Secretariat is invited to provide brief oral reports on its activities at G20 EWG meetings.Footnote 32 Since the G20 lacks a formal secretariat, the Group is not offered a similar platform within APEC, although information exchange is facilitated by the two groups’ overlapping memberships.Footnote 33 Indeed, the APEC EWG guidelines encourage APEC members undergoing a VPR through the G20 to share the results with members of the APEC EWG ‘in order to transfer lessons learned from that process to all Members’ (APEC EWG 2013, 6).Footnote 34 To support mutual learning, APEC’s capacity-building workshops have also featured talks on G20 experiences (APEC EWG 2015, 2017).Footnote 35

Similarly, the Friends have occasionally held observer status in G20 meetingsFootnote 36 while ‘invited guests’ from non-Friends countries and international organizations have also participated in the Friends’ six-monthly meetings.Footnote 37 Friends’ side events on the margins of meetings of the UNFCCC and the World Bank and IMF have also seen the involvement of representatives from G20 and/or APEC countries such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Mexico (Friends 2017; Sanchez Reference Sanchez2017). In 2013, New Zealand’s then-Ambassador to the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was invited to present on peer review at a workshop hosted by the Russian G20 Presidency.Footnote 38

Behavioural mechanisms are also present in how the three groups interact, with various examples of institutions being impacted by the functional and strategic behaviour of their members and other actors. Indeed, as discussed in more detail in Section 5.5, such mechanisms go to the heart of the Friends’ activities, which are directed at monitoring and influencing the FFSR activities of the other two groups, including through lobbying and capacity-building activities. These behavioural dynamics are also a product of interlocking memberships. Countries such as the United States and China have helped to push reform commitments and peer review efforts forward in both the G20 and APEC, while New Zealand has actively sought to promote the FFSR agenda through its APEC membership.

5.5 Micro-Level Management

As noted, there is a significant level of consistency between the G20, APEC, and Friends with regard to the core norm they promote. Although their approaches vary to some extent, the three groups also fulfil governance functions in a synergistic fashion. Their activities further complement each other in terms of their geographical scope. As we discussed earlier, this relatively symbiotic relationship may in part be explained by the groups’ overlapping memberships.

In addition to such overlaps, the different groups and their members also engage in formal and informal coordination efforts. This includes creating spaces for attending one another’s meetings and external events and, in the case of APEC, institutional encouragement to its members to share experiences from the G20 peer review process with other members.

Most interaction management between the three groups seems to take place informally, however, including through meetings on the sidelines of international events;Footnote 39 outreach to Friends members for their expert knowledge;Footnote 40 and outreach of Friends members to other countries, particularly in advance of G20 summits.Footnote 41 The Friends’ Communiqué was furthermore drafted with the involvement of both the United States and France as well as the IEA, IMF, and OECD.Footnote 42

Even where interaction has not been direct, it is furthermore clear that the G20, APEC, and Friends have kept abreast of one another’s FFSR activities. As described earlier, APEC economies were well aware of the way the G20 was approaching its FFSR pledge and its VPRs, which helped inform its decision to follow a slightly different tack. Furthermore, Yoshida notes that APEC took care to ensure that the peer reviews undertaken under APEC did not undermine momentum in the G20 by co-opting members from this Group.Footnote 43 Meanwhile, APEC developments were also tracked by G20 members. For instance, observing that progress under the G20 was less forthcoming than under APEC, the United States volunteered to undergo a VPR under the former, rather than the latter.Footnote 44

Through what can be characterized as a ‘broker’ role, the Friends have also proactively sought to enhance the complementarity of the three groups’ actions. For instance, developments at the G20 provided New Zealand and others with leverage to ensure similar efforts were undertaken under APEC, both in terms of the adoption of reform commitments as well as the introduction of a peer review process in this area.Footnote 45 In undergoing its peer review, New Zealand also involved representatives from China, which in turn informed China’s understanding of what the review could look like in a G20 context.Footnote 46

5.6 Conclusions

Over the past decade, more than a dozen international energy, economic, environmental, and trade institutions have sought to promote FFSR in different ways. They have done so by providing financial and other incentives to implement reform, coercing states to undertake reform, diffusing the emerging norm of FFSR, and disseminating information about fossil fuel subsidies and their adverse impacts. However, little is still known about how the efforts of these various institutions ‘add up’, and the extent to which the activities in different institutions complement or contradict each other. This chapter has sought to shed light on this question by assessing the coherence of the institutional complex governing FFSR.

At the meso level, we identify an emerging division of labour in this subfield. Institutions such as the G20, APEC, and Friends play an important role in setting agendas and commitments (and to a lesser extent, sharing information), while organizations such as the OECD, IEA, and IMF engage in information-sharing on the scale of subsidies and their impact. In parallel, organizations such as the World Bank and Global Subsidies Initiative have emphasized operational activities for capacity-building and implementation purposes. Where activities do overlap, they generally appear to reinforce one another.

Zooming in on a subset of FFSR actors, the activities of the G20, APEC, and Friends have been among the most prominent in the field. Together, these three groups cover forty-one economies and a range of activities from standard and commitment setting, information and networking, operational activities, to financing. We find their efforts in this regard to be consistent with one another, and in many cases complementary. For instance, while their membership partially overlaps, the G20 and APEC’s peer review activities target different countries, thereby expanding the geographic reach of such efforts. In addition, many of the efforts undertaken by the Friends and their members have been intentionally directed toward enhancing reform efforts under the G20 and APEC. This high level of consistency appears to be the result of planned coordination between institutions and overlapping memberships, as well as a proactive brokering role taken on by some countries, including the Friends.

Despite these synergies, country-level progress on reform remains limited. Public funding for fossil fuel consumption and production continues to total many billions of dollars each year, including in G20 and APEC economies (Bast et al. Reference Bast, Doukas, Pickard, van der Burg and Whitley2015; Rentschler and Bazilian Reference Rentschler and Bazilian2017). While the many domestic political factors impeding FFSR undoubtedly play an important role in this, international cooperation can, at least in theory, help to overcome some of these barriers (see Section 5.2). But if this is the case, why has progress been halting? And how does the multiplicity of institutions governing this field factor in? We return to these questions in Chapter 8, where we take stock of international institutions’ effectiveness in governing FFSR to date.