Appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) is essential for adequate development and survival(Reference Shaker-Berbari, Ghattas and Symon1). The WHO recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of age, introducing adequate complementary food thereafter, and ensuring that breast-feeding is continued at least until the child is 2 years of age(2).

Infants represent a particularly vulnerable population during emergencies(Reference Scime3); hence, facilitating adherence to recommended IYCF practices becomes vital. In these situations, infant formula is not a safe feeding practice because it poses important risks to infants’ health due to the lack of optimal sanitary conditions, such as clean water, and compromised access to health care. These risks are even higher if infants were being breastfed pre-emergency(Reference O’Connor, Burkle and Olness4). Breast-feeding is particularly vital during emergencies because breast milk adapts its composition to meet the nutritional needs of infants and to provide tailored protection against infection-related agents(Reference Scime3,Reference Sankar, Sinha and Chowdhury5) . Prior evidence highlights the importance of breast-feeding during emergencies. A study reported that after the Southeast Asian tsunami in 2004, children who were artificially fed had three times higher rates of diarrhoeal episodes than those who were breastfed(Reference Adhisivam, Srinivasan and Soudarssanane6). Similarly, after the 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta and Central Java, there was a strong association between the receipt of infant formula and diarrhoea among infants(Reference Hipgrave, Assefa and Winoto7).

To protect and support breast-feeding during emergencies, donations and distribution of infant formulas need to be limited and regulated. Breast-feeding is a fragile practice in many societies that can be easily disrupted by exogenous factors. Prior studies have documented an association between receiving infant formula donations during emergencies and changing feeding practices(Reference Sankar, Sinha and Chowdhury5,Reference Binns, Lee and Tang8) . This has been recognised by different international guidelines, such as the International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes (the Code)(9), the World Health Assembly(10) and the Operational Guidance on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies (OG-IFE)(11). These guidelines emphasise that during emergencies, controlling donations and the distribution of infant formulas is of particular importance to protect breast-feeding(9–11). The World Health Assembly urges all state members to ensure evidence-based and appropriate IYCF during emergencies(10).

Emergencies impose important challenges to societies and governments, and protecting and supporting breast-feeding become essential. Although breast-feeding promotion is fundamental, it is not the focus of action once an emergency strikes. Prior successful interventions suggest that there are feasible mechanisms to protect and support breast-feeding during emergencies. For example, after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, 193 baby tents were established to provide a safe place for mothers to breastfeed; as a result of the rapid programme scale up, breast-feeding practices were adequately protected and remained undisrupted(Reference Ayoya, Golden and Ngnie-Teta12).

The 2017 Mexican Earthquakes and the National Breastfeeding Strategy

On September 2017, two earthquakes struck Mexico and affected communities in the south and central part of the country, causing casualties (approximately 500 deaths) as well as physical structural damage and affecting more than 12 million people(Reference Ureste and Aroche13). This generated a fragile context for breast-feeding in a country with underlying challenges in this area, where the prevalence of exclusive breast-feeding is low (30·8 %)(14), compared with the global prevalence (38 %) and is far from the WHO global target (i.e. 50 % by 2025(10)).

When the earthquakes struck, the country had a National Breastfeeding Strategy(15) that was generally consistent with the Code, but it made no mention of how to protect and support breast-feeding during emergencies. Similarly, the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control (CENAPRECE in Spanish) had a manual for emergencies; however, it only mentioned some general specifications for infant formula donations(16). Hence, there were important operational gaps to adequately protect and support breast-feeding during emergencies.

The present study documents the barriers and enablers of breast-feeding protection and support after the 2017 earthquakes in Mexico. It provides important lessons and pending policy actions for emergency preparedness and responses that may resonate at an international level.

Methods

The study follows a phenomenological qualitative approach to examine the actions and omissions of different social actors regarding the protection and support of breast-feeding in the aftermath of the earthquakes. A phenomenological approach gathers data about an event from the perspective of those who were involved(Reference Cassell and Symon17).

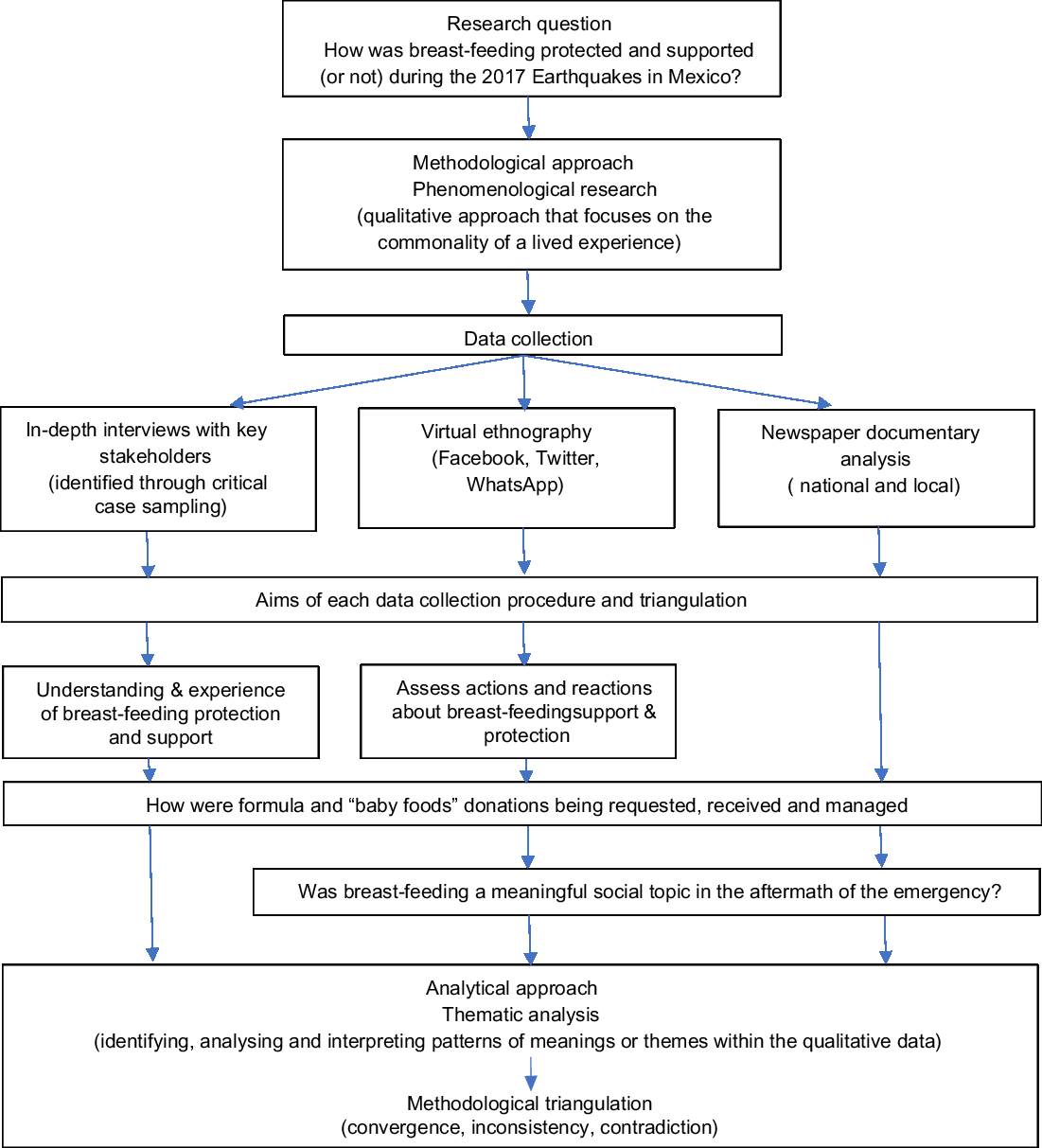

Data collection took place between September 2017 and May 2018. Three different qualitative techniques informed the research: in-depth interviews with key informants, virtual ethnography and newspaper documentary analysis. This approach allowed triangulation(Reference Corbin and Strauss18). Figure 1 summarises the methodological framework of the study.

Fig. 1 Analytical framework, data collection and data analysis of actions to protect and promote breast-feeding, 2017 Earthquakes in Mexico

In-depth interviews

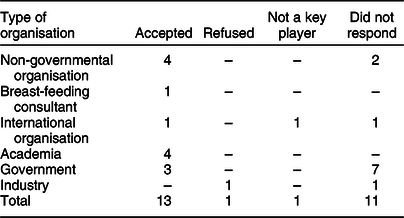

The selection of key informants followed a critical case sampling approach, which is a type of purposive sampling technique that is useful in exploratory qualitative research in which those who are particularly important in an event are selected(Reference Patton19). To identify important cases, the research team mapped actors involved in IYCF actions during the aftermath of the earthquakes from all sectors (i.e. government, industry, academia, international organisations and non-governmental organisations). All mapped participants (n = 26) were invited to participate, and thirteen accepted (see Table 1).

Table 1 Key informants invited to participate in the study of actions to protect and promote breast-feeding, 2017 earthquakes in Mexico

Interviews were conducted face-to-face and were based on a semi-structured guide based on a prepared set of questions (included in Supplemental Material) but encouraged the inclusion of unexpected but relevant information(Reference Silverman20). Written informed consent was granted in all cases. The interviews had an average duration of 50 min and were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim and deidentified before coding. Through a thematic approach, two of the authors (M.V.C. and C.P.N.) designed a codebook by consensus and coded the qualitative data in NVivo(21).

Virtual ethnography

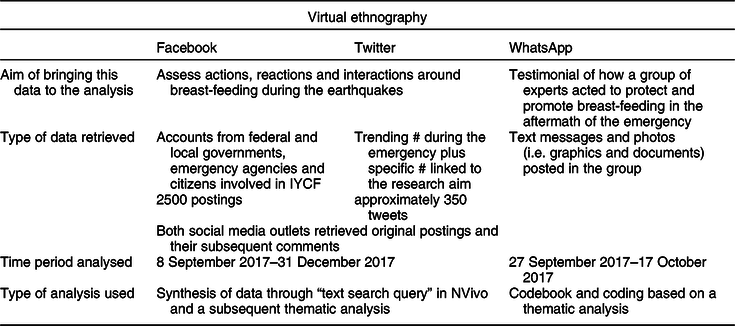

Because social networks played a key role during the emergency, virtual ethnography was a key part of the analysis. As portrayed in Table 2, this approach used two strategies. First, data from two key social media outlets (i.e. Facebook and Twitter) were analysed, which provided rich information about the visibility of breast-feeding in the aftermath of the earthquakes as well as actions and reactions to protect and support breast-feeding. Second, we gained access to a WhatsApp group of breast-feeding experts that provided rich examples of actions taken.

Table 2 Framework and scope of the virtual ethnography of the study of actions to protect and promote breast-feeding, 2017 earthquakes in Mexico

IYCF, infant and young child feeding.

Facebook and Twitter were included in the analysis due to their massive use and popularity in Mexico. According to the National Household Survey of Availability and Use of Information Technologies 2017, approximately 77 % of Mexicans aged 6 years and over had a smart phone and, among them, 98 % were users of Facebook and 57 % were active on Twitter(22). The mechanisms to retrieve data varied by social media outlet (see Table 2). Facebook accounts from federal and state governmental agencies of the affected states, emergency attention agencies and citizens involved in any topic related to IYCF were traced and analysed during the period 8 September 2017–31 December 2017. Approximately 2500 posts were retrieved. In Twitter, the search involved defining popular hashtags during the earthquake (i.e. trending #) as well as those related to the research, which led to the inclusion and individual assessment of ten hashtags. Trending hashtags included #19S, #FuerzaMexico and #PrayforMexico, while specific hashtags for research purposes included #sismo, #sismosMexico, #donativo, #donacion, #centrodeacopio, #albergue and #lactancia. Approximately 350 tweets were retrieved.

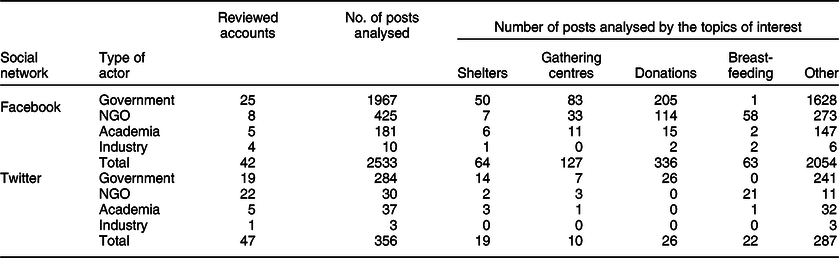

For both social networks, comments on original posts were also included. The analysis followed three steps. First, posts were classified by the type of actor and by topic (see Table 3). Then, they were systematised in NVivo through the tool ‘text search query’, and word trees were generated to assess key words/terms and their differential use by type of actor through a thematic approach.

Table 3 Facebook and Twitter postings to analyse breast-feeding actions by type of actor and topic, 2017 earthquakes in Mexico

NGO, non-governmental organisations.

The WhatsApp group included experts from the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Committee (i.e. advocacy groups and non-governmental organisations, international agencies and academia) as well as the National Institute of Perinatology and the International Baby Food Action Network. It was created in the aftermath of the second earthquake (27 September 2017) to help coordinate actions to protect and support breast-feeding mothers. The analysis provided insights into the barriers and enablers to protecting and supporting breast-feeding. It included texts and photos that provided a rich narrative of the experiences. The period analysed was from 27 September 2019 to 17 October 2019. The texts were systematically coded through a thematic approach. As in the in-depth interviews, two of the authors (M.V.C. and C.P.N.) designed a codebook by consensus and coded the qualitative data in NVivo. The photos were used only as complementary materials.

Documentary analysis of newspapers

Three major national newspapers and one local newspaper from the most affected states were included. They were selected based on wide national/local readership and electronic availability. The search was conducted electronically and was complemented by physical searches in libraries to verify that there were no discrepancies between the physical and electronic versions. To contextualise the emergencies, all information about the emergencies published in the two immediate days after the earthquake was retrieved. In addition, for the remaining period, a focused search was performed to identify information potentially related to the protection and support of breast-feeding. Hence, the period analysed was between 8 September 2017 and 19 October 2017. More than 3400 informative notes, articles, columns and publicity were retrieved. These were scrutinised by two members of the research team (C.P.N. and research assistants), and only those that informed the research were systematised for further analysis. The materials were then organised and synthesised into preidentified themes: (i) government actions, (ii) gathering centres and shelters and (iii) breast-feeding.

Triangulation

Triangulation aimed to avoid the biases of a mono-methodology strategy. It addressed three possible outcomes: convergence, inconsistency and contradiction.

All key informants provided written informed consent, and information was deidentified before transcription and coding. For the WhatsApp group, participants granted consent in a joint phone call. The rest of the information is publicly available (i.e. Twitter, Facebook and newspapers).

Results

In-depth interviews

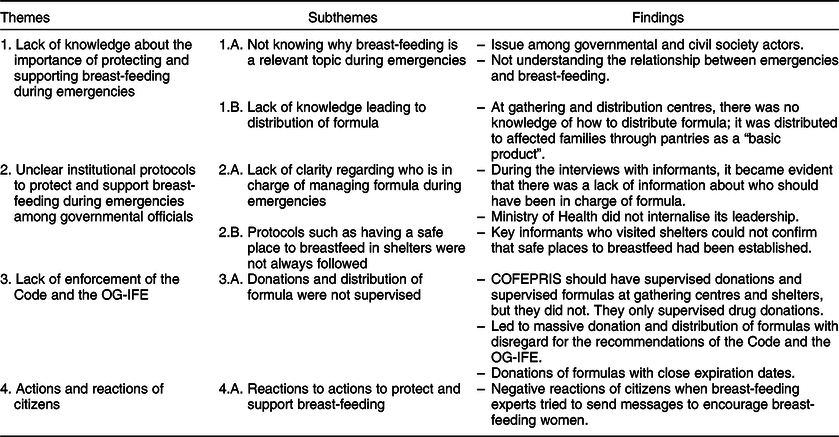

Four themes emerged from the interviews: (i) lack of knowledge; (ii) unclear institutional protocols; (iii) lack of enforcement of the Code and the OG-IFE and (iv) citizens’ actions and reactions (see Table 4).

Table 4 Themes and subthemes emerging from in-depth interviews to assess breast-feeding related actions, 2017 earthquakes in Mexico

OG-IFE, Operational Guidance on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies.

Lack of knowledge about the importance of protecting and supporting breast-feeding during the emergencies particularly emerged among informants from the government and civil society organisations that managed gathering centres. Comments such as ‘are you really conducting a study about breastfeeding during emergencies?’ emerged during the interviews. This lack of knowledge was also exemplified by the consideration of formula as a ‘basic item’ when distributing aid pantries. An official of a gathering centre explained, ‘Formulas were delivered in all emergency basic pantries… they included rice, beans, tuna, plus a kid basket, which included milk, diapers, some medicines, soap, and shampoo, very basic things’.

The second theme was the lack of protocols to protect and support breast-feeding among government officials. This became evident when interviewing officials from diverse state agencies. For example, when inquiring about how formula donations had been managed, an official from the Ministry of Health stated, ‘During emergencies, food supplies are managed by another agency … I think that it is managed by the Ministry of Social Development’. However, a representative from an international organisation stated, ‘We had meetings with the Ministry of Health that is in charge of breastfeeding. But they told us that the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development was managing the shelters and that it was not a responsibility of the Ministry of Health’. Similarly, when officials from the Ministry of Social Development were interviewed, they explained that formula was mainly managed through shelters and gathering places and that these were coordinated ‘by the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Social Development’. Although the Ministry of Health should have led efforts to protect and support breast-feeding, this was not a topic internalised in their action lines, as evidenced in the following quote: ‘The priority of the Ministry of Health varied according to the timing. During the earthquake, the most important action was to save lives, rescue, reconvert hospital beds, and provide care … In the next phase, to ensure that shelters had enough food and care about vector-borne diseases, and at all times, there was a permanent mental health campaign’. No information about IYCF emerged even after the informants were prompted.

A theme that strongly emerged through the interviews was the lack of enforcement of the Code and the OG-IFE. The Ministry of Health (through the Sanitary Risks Protection Commission, COFEPRIS in Spanish) should have supervised formula donations. However, according to interviews with people working at gathering centres, COFEPRIS only supervised drug donations. This led to a situation in which formula was being massively donated and distributed with disregard for the recommendations of the Code and the OG-IFE. A key informant from one of the major gathering centres in Mexico City during the emergency stated that formula was ‘something basic’ and was commonly requested by government officials without any further specification: ‘Formula requests were never specific. We did not know who the infant was; we would just send it, infant formula … I know that there are differences depending on the months, but I don’t know them because my kid was breastfed’. Key informants from academia and breast-feeding experts highlighted that there was an indiscriminate distribution of formula. One of the informants stated strong suspicions of industry donations (which should have been regulated), highlighting ‘When you see twenty different cans of formula in a shelter, it is likely that they come from citizens, but when you see several boxes of the same formula nicely packed, then you believe it is unlikely that they come from citizens’ donations’. There were additional issues with formula donations. A key informant from an international agency stated, ‘There were difficulties with infant formula donations … some had very close expiration dates. We even have graphical evidence … this happened in Juchitán, Oaxaca, and I imagine that it could have happened in other places’.

Finally, another theme that emerged in the interviews – particularly with key informants from academia and breast-feeding experts – was the actions and reactions taken by citizens. In one of the interviews with a key informant from academia, it was documented that because of the massive lack of information about the risks of infant formula and the importance of protecting breast-feeding, several researchers and breast-feeding experts started writing messages on the formula cans available at gathering centres and shelters. These messages aimed to provide some information to mothers who received these products. However, there were many negative reactions to these actions, as exemplified by the following quotes: ‘When I started labeling cans of formula with breastfeeding support messages, some people liked it, but some others did not… those against the messages would say things such as, ‘Women are already nervous enough; how would breastfeeding messages help?’ and ‘In emergency times, when some people do not have enough food and you come with the message ‘Don’t give formula’, people think that you are denying food to babies, and it then becomes very touchy’.

Virtual ethnography

A separate analysis was performed for Facebook/Twitter and WhatsApp. As portrayed in Table 2, Facebook and Twitter followed the same analytical approach; hence, their analysis was performed jointly, while a different analytical strategy was used for WhatsApp.

For Facebook and Twitter, the ‘text search query’ tool led to the identification of key terms/words in the social networks. ‘Pantries’, ‘foods’, ‘kits’, ‘health’, ‘gathering’, ‘shelter’, ‘breastfeeding’, ‘baby’, ‘baby milk’ and ‘milk’ emerged as the key terms in the analysed postings that led to the systematisation of the data into key themes: (i) donations and (ii) actions and reactions to protect breast-feeding during the emergency.

The first theme revealed that there was a strong call for donations in the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes. The federal and state-level governments called society to donate in the gathering centres. Donation requests were ambiguous, using words such as ‘groceries’, ‘nonperishable foods’, ‘canned foods’, ‘food for infants’, ‘baby kits’, and ‘pantries’, among others. In other cases, donation requests explicitly stated ‘powdered milk’ and ‘infant milk’, which frequently led to formula donations. For example, on the Facebook account of the National System for Family Development, a radio interview with a high-level official was published that stated, ‘… we are trying to assemble the largest possible number of pantries, and we are still in need of infant food’. The radio interviewer asked if she could be more specific, and she replied, ‘Powdered milk, cereals, feeding bottles’. She did not mention any portion or type of milk, but she stated that in each pantry box, a baby bottle was included. This was an open request for infant formula by the government that evidences the lack of adherence to the Code and the OG-IFE.

Postings on Twitter accounts from government agencies confirmed the receipt of donations of ‘canned milk’ from one of the main infant formula producers. A posting on 7 October stated, ‘We received 3700 cans of milk in Juchitan’s shelter from (name of the company)… Thanks!’ Similarly, on social media, formula-related companies stated that they had provided donations, such as ‘1 million food portions’ or ‘675 thousand portions of baby food’. These companies were invited to participate in the study; one refused the interview, and the other did not respond to the invitation. Hence, the specificities of these donations could not be verified.

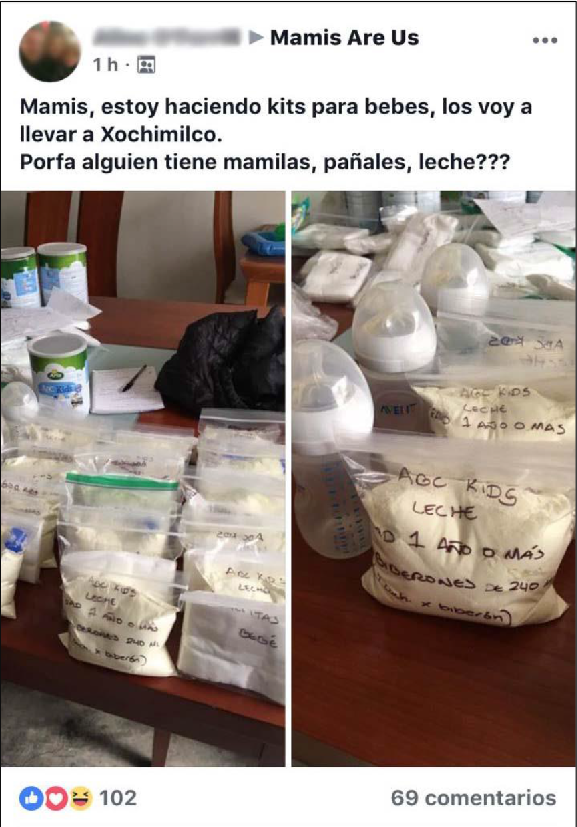

Social networks also provided evidence about generalised donations of formula from citizens, probably driven by two factors: the way in which donations were requested and the generalised idea that formula is as good or even better than breast milk(Reference González de Cosío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell23). Some citizens gathered infant formulas and baby bottles to assemble ‘kits’ like the one shown in Fig. 2 (i.e. formula divided into plastic bags for smaller portions and distributed to shelters with a baby bottle).

Fig. 2 “Baby kits” assembled by citizens perceived to support infants affected by the 2017 earthquakes in Mexico

The second theme that emerged relates to actions and reactions to protect breast-feeding. Experts from the Research Center in Nutrition and Health at the National Institute of Public Health (INSP in Spanish) published several Facebook posts with the aim of supporting breast-feeding mothers. For example, a post from 21 September 2017 stated, ‘The best food for your baby is breast milk. During the emergency, mothers can still breastfeed. The “scare” (of the earthquake) does not affect breast milk’. This message intended to provide information regarding a popular belief that with a ‘sudden scare’ (i.e. susto in Spanish), breast milk becomes sour. However, within seconds of posting, negative reactions emerged, such as, ‘I consider this an inadequate and insensitive message… We ask you to stop writing these messages … Mothers and families that have been affected by this situation (the earthquake) have gone through a lot already’. However, some key informants suggested that infant formula-related companies prompted some of these messages.

The WhatsApp analysis highlighted the relevance of having previously established interinstitutional teams of experts. Two themes emerged: actions directed to the vulnerable population and actions directed to the authorities. In the first theme, two different subthemes emerged. The first centred on an immediate strategy to send key messages to the population. During the first 2 d after the earthquake, there was concern about the amount of formula donated in gathering centres and shelters and an increasing sense that actions needed to be taken as a group. The members of the group organised to visit gathering centres with the goal of placing messages on formula cans. In the initial step, they wrote messages with markers, such as, ‘Breast milk is the best option’ or ‘Your milk did not go sour’. During the subsequent days, standardised messages were printed and glued to the cans, such as, ‘Do not use unless you were not breastfeeding before the earthquake’ and ‘Breast milk protects your baby from disease’.

The second subtheme required more planned activities. Between the third and fourth days, the expert group converged on the need to generate materials to communicate the relevance of protecting and supporting breast-feeding in shelters and gathering centres. They designed a poster responding to the question, ‘Why is it important to protect breastfeeding during an emergency?’ Using concise language, the poster informed about the benefits of breast milk and the risks of using formula and provided key recommendations for shelters and gathering centres to protect breast-feeding (see Supplemental Materials). However, designing and distributing this poster faced several time barriers. Even though the poster was initially disseminated through social media (mainly Facebook and Twitter), by the time it was printed, many shelters and gathering centres had already closed.

The second theme that emerged in the WhatsApp analysis involves the way experts organised and wrote a letter to the Ministry of Health demanding an end to the massive distribution of formula. The message also stated the frustration of not receiving an answer. Subsequent conversations with the WhatsApp members revealed that this letter received a response in April 2018 – almost 7 months after the earthquake.

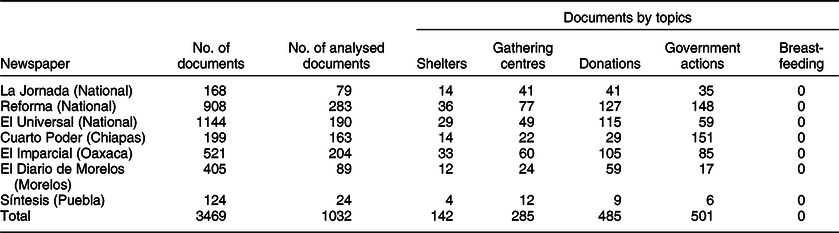

Documentary analysis of newspapers

Notes, articles, columns and publicity (n = 3469) were retrieved from three national newspapers and four local newspapers from the most affected states. From the initial analysis, 2437 documents were excluded because they were unrelated to the topic (i.e. they addressed the emergency in terms of the number of victims or damage to infrastructure or were general narratives about the disasters). A total of 1032 documents were coded into four nonexclusive categories: shelters, gathering centres and donations, government actions and breast-feeding (see Table 5). With regard to the first category, 142 documents referred to shelters, 285 to gathering centres and 485 to donations. These included documents issued by the government, non-governmental organisations or private organisations calling citizens to donate to shelters and gathering centres. The words used in the documents varied. While some were very specific and established a list of products, others were more general, including words such as ‘pantries’, ‘canned foods’ and ‘food for babies’. What was common in both sources were words that may have led to formula donations, such as ‘powdered milk’ and ‘food for babies’.

Table 5 Analysed documents from newspapers to assess breast-feeding actions by topic, 2017 earthquakes in Mexico by topic*

* We did not include a specific newspaper from Mexico City because all national newspapers have a section about the City.

The second category focused on identifying governmental actions; 501 documents fell in this category. The analysis confirmed three sets of actions: calling for donations, reporting the amount of donations received and describing how donations were distributed. The analysis identified ambiguous use of language such as ‘powdered milk’, ‘infant milk’ and ‘baby food’ that does not allow the language to be traced directly to breast milk substitutes, although it is likely to include them. Among the notes describing how donations were distributed, none referred specifically to such products.

The third category implicitly searched for any mention of the word breast-feeding. This was an empty category, exemplifying the invisibility of this topic.

Triangulation

The analysis converged in three aspects. First, in-depth interviews, virtual ethnography and newspaper documentary analysis underlined the lack of enforcement of the recommendations regarding breast-feeding during emergencies. The virtual ethnography and documentary analysis converged in finding a strong call to donate formula. These calls were generated by gathering centres as well as local and state governmental agencies using ambiguous terms such as ‘baby milk’ and ‘baby food’, which led the public to donate infant formula. Second, a common phenomenon that emerged in all data sources was the lack of protocols in relation to how to manage and distribute formula. This lack of protocols led to actions such as including a ‘baby kit’ in emergency basic pantries as well as distributing formula through unsafe mechanisms that placed both breastfed and artificially fed babies at risk. Third, the in-depth interviews and the virtual ethnography strongly suggested that breast-feeding was an unimportant area of action from a social and policy perspective. This was tied to a massive lack of information about the risks of formula use during emergencies as well as to the generalised idea that formula is as good as or even better than breast milk. Hence, in the social imaginary, donating bottles and formula was a justified humanitarian action that, when confronted by breast-feeding experts, led to negative emotions and reactions. Furthermore, this coincided with the fact that in the newspaper documentary analysis, not a single piece on breast-feeding could be found, suggesting that breast-feeding is an ‘unimportant’ or non-salient topic during emergencies.

Discussion

The current analysis profited from different data sources; together, they reached important saturation around issues such as donations, lack of information, insufficient protocols and violations of pre-existing frameworks such as the Code.

The inclusion of infant formula in boxes of goods distributed to the affected population was normalised by citizens, individuals working at the shelters and gathering centres and the government. This is partially an outcome of the general belief that formula is as good as breast milk(Reference González de Cosío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell23) as well as the cultural notion that breast-feeding may be unfeasible during stressful periods. Hence, there was almost no room left to think about the potential negative implications of massively distributing breast milk substitutes. Excluding academia and breast-feeding experts, the interviewed key informants showed a lack of knowledge on the relevance of protecting and supporting breast-feeding during emergencies. Hence, a lesson learned is the need to adequately inform the public and those in charge of gathering centres and shelters about the risks of distributing breast milk substitutes during emergencies.

The interviews revealed that it was unclear who was in charge of protecting and supporting breast-feeding during emergencies. Informants named at least four different agencies. Protocols and guidelines need to be ready before disasters or emergencies strike. An example of the relevance of timing is the poster designed by experts that could not reach shelters and gathering centres in a timely manner. The lack of protocols also led to food safety issues. This was exemplified by mothers assembling ‘baby kits’ and placing formula in plastic bags as well as formula donations with expiration dates within a few weeks of delivery. This suggests that protocols should also be in place to safeguard the health and well-being of non-breastfed babies.

It is unclear why and how the industry donated formula and ‘other baby foods’. The donation and further distribution of such products suggest violations of the Code that the government did not acknowledge, even after a group of experts demanded actions to stop such donations and distribution during the emergency. Prior studies have highlighted the deleterious effects of distributing formula during emergencies to children’s and households’ well-being(Reference Adhisivam, Srinivasan and Soudarssanane6,Reference Hipgrave, Assefa and Winoto7,Reference Assefa, Sukotjo and Winoto24,Reference Rawas25) . Actions are required to emphasise this message among those in charge of emergency preparedness and response, as well as to citizens.

This study suggests a lack of relevance and visibility of breast-feeding during the emergency and further identifies the absence of breast-feeding in emergency preparedness and response plans. An indirect way of underscoring this absence is the fact that key governmental actors that should have been involved in protecting and supporting breast-feeding during the emergency did not reply to the invitation to participate in the study.

Another finding from this study is the relevance of pre-existing networks of experts such as the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Committee. Despite the invisibility of their actions in newspapers, they distributed information through different outlets. However, to magnify their impact, they need to work in liaison with government and international agencies that act in the immediate onset of emergencies. Additionally, prior research in Mexico(Reference González de Cosío, Ferré and Mazariegos26) has highlighted that from an institutional perspective, the country lacks coordination mechanisms. According to the becoming breast-feeding-friendly gear model(Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Curry and Minhas27), such coordination mechanisms are essential.

In practical terms, key lessons can be drawn in terms of preparedness and response regarding IYCF. First, preparedness actions should include the evaluation of existing institutional breast-feeding protocols. Second, specific guidelines should be generated to (i) prevent donations of breast milk substitutes and feeding equipment (including vague wording such as ‘baby kits’ or “powdered milk) and (ii) specify how to handle donations if they arrive. Third, it is necessary to establish the mechanism through which the Ministry of Health will protect and support breast-feeding with support from an expert advisory committee including academics, lactation counsellors, civil society organisations and key government stakeholders. It is also necessary to anticipate which governmental agencies will be involved during an emergency and engage them in formulating the protocols. Fourth, it is important to set standards and provide guidance for governmental and non-governmental organisations that run shelters during emergencies. Such guidelines should include the provision of private and clean spaces to breastfeed; information about the importance of breast-feeding support and protection during emergencies; channels to obtain support from breast-feeding counsellors; and clear information about how to procure breast milk substitutes where needed. Fifth, health frontline workers should be constantly trained on the relevance of supporting and protecting breast-feeding during emergencies. A challenge that should be underscored is the scarcity of a well-trained workforce in breast-feeding. This should be prioritized. Finally, media-friendly key messages should be developed that are ready for dissemination through multiple channels and are adapted for different literacy levels and local languages.

The study has some limitations. First, the data were collected in a retrospective manner and not during the emergency. In future studies, it would be very helpful to collect data during the crisis. However, to balance this, the study benefitted from a virtual ethnography analysis. Such an approach is not only relevant but also novel. A second limitation was that some key informants refused to participate or did not reply to our invitation. However, it should be stressed that they decided not to participate in the study. Third, future studies should aim to assess breast-feeding protection and support during emergencies through mixed methods, which may allow us to account for quantitative aspects such as the number of families that receive donations of breast milk substitutes. These types of analysis require a survey approach and the resources to implement this approach. Finally, an important limitation of the study is that mothers who received formula or who were breast-feeding during the emergency were not interviewed. Emergencies are stressful and may cause trauma to mothers. Future studies should aim to collect these data so that better preparedness and response interventions can be implemented to safeguard the well-being of women and children.

In conclusion, this study identified key barriers related to knowledge and information, a lack of specific protocols and guidelines, inefficient institutional responses and violations to existing frameworks that were not correctly monitored and enforced by the government. This led to the distribution of formula that posed health risks to babies. The study also identified enablers, such as the relevance of pre-existing networks of experts. The relevant actors should embrace the lessons highlighted in this study because countries like Mexico are likely to experience future emergencies.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank UNICEF Mexico’s Office for the support in providing funding rapidly, which was a key element in the feasibility of this work. In addition, the authors thank the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Committee in Mexico; their support in the aftermath of the emergency and in subsequent discussion of the findings was of great relevance in drafting this manuscript. Financial support: This work was supported by UNICEF. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests. Authorship: M.V.C. proposed the methodology to UNICEF Mexico’s Offices; wrote the technical proposal; led the conduction of the study; contributed to data analysis and was the PI in writing the report. C.P.N. contributed in writing the technical proposal; organised and conducted fieldwork instruments; contributed to data analysis; contributed in drafting the report. S.B.M. conducted fieldwork; contributed to data analysis; contributed in drafting the report. M.S.A. and P.V. proposed the study, gave technical inputs during the development of the study and key insights for the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Iberoamericana All key informants provided written informed consent, and information was deidentified before transcription and coding For the WhatsApp group, participants granted consent in a joint phone call (witnessed among each other). The rest of the information is publicly available (i.e. Twitter, Facebook and newspapers)

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002359