Why do people obey laws and accept court decisions? Decades of studies have pointed to the importance of procedural justice (Reference EastonEaston 1965; Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988; Reference Thibaut and WalkerThibaut and Walker 1975; Reference TylerTyler 1984; Reference Tyler1990; Reference Walker, Thibaut and AndreoliWalker et al. 1972). Procedural justice can promote satisfaction, belief in the legitimacy of authority, and willingness to comply and cooperate with the law (Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt and Bradford 2016; Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988; Reference Paternoster, Brame, Bachman and ShermanPaternoster et al. 1997; Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 1984, Reference Tyler1988; Reference Tyler1990). Scholars generally believe that procedural justice can play the role of a “cushion of support,” alleviating the negative emotions elicited by unfavorable outcomes (Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Hasisi and MargaliothJonathan-Zamir et al. 2016; Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988; Reference TylerTyler 1984, Reference Tyler1990; Reference Tyler, Boeckmann, Smith and HuoTyler et al. 1997; Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler and Allan Lind 1992). People view “bad” distributive outcomes more positively if they result from a fair procedure they experience as fair. The importance of procedural justice has been demonstrated in various settings, throughout North America, Europe, and Asia, and by a wide range of methodologies (Reference MacCounMacCoun 2005: 371).

Do these patterns hold for China, a country with a different legal tradition and a frequently changing system? How do Chinese litigants evaluate the courts? What is the role of procedural justice in their evaluations? Do they lose confidence in the law and the courts? These questions are crucial to whether China's ongoing legal reforms will create confidence and legitimacy among the people. All political institutions, including those in authoritarian regimes, need some level of popular support (Reference Garoupa and GinsburgGaroupa and Ginsburg 2015; Reference Ginsburg and MoustafaGinsburg and Moustafa 2008). In the absence of legitimacy, people may be less compliant with the law and court decisions (Reference FriedmanFriedman 2016; Reference HeHe 2005; Reference He and XiaoHe and Xiao 2019; Reference TylerTyler 1990). At the extreme level, a lack of confidence in the normal channels may lead to protests (Reference LeeLee 2007; Reference Su and HeSu and He 2010), bribery (Reference LiLi 2012), petitioning (Feng and He 2018), or other means of circumventing the system.

Dissatisfaction with China's court system is widespread: complaints to upper-level governments about the courts, also known as petitions (涉法上访), reached 4.14 million in 2005, just below the total number of first-instance civil cases. In 2009, 210,943 petitions were filed with the Supreme People's Court (SPC), compared to 140,511 in 2006 (figures are from the working reports of the SPC). This negative view toward Chinese legal institutions has been echoed by gruesome media reports on litigants' grievances (Reference KahnKahn 2005; New York Times 2015; Reference TatlowTatlow 2016) in which frustrated litigants have even murdered their judges (Wenweipo 2016). Understanding the gravity of the situation, President Xi Jinping has urged the courts to make sure that “the masses feel fairness and justice in every judicial case.”

Studies have generally found that outcomes (i.e., the favorability of a decision) or distributive justice (whether the outcome is distributed fairly) play a dominant role in Chinese people's views on the court system. Reference Michelson, Read, Woo and GallagherMichelson and Read (2011: 171) found that their survey participants conflated procedural justice with distributive justice. Similarly, Reference Gallagher, Wang, Woo and GallagherGallagher and Wang (2011: 225, 232) have found “personal efficacy” important in assessments of the labor dispute resolution system. Overall, laborers are more concerned about outcomes, but there is also a generational gap in procedural justice: the post-socialist group of laborers emphasizes procedural justice, while the socialist group stresses substantive justice (see also Reference GallagherGallagher 2017). Reference Feng and CaoFeng and Cao (2014) have described the importance of substantive justice for litigants in a dispatched tribunal in rural China: for litigants' own good, judges imposed their “expected outcomes” on the litigants, regardless of the litigants' intentions. Reference Feng and CaoFeng and Cao (2014) argue that this approach, arguably ignoring the litigants' own voices and harming their self-dignity, contradictorily enhances the litigants' recognition of the court's decision.

The dominant role of outcomes may not surprise those who believe in the importance of culture and tradition. For them, the minimal role of procedural justice can be attributed to the fact that procedure has historically been neglected, or viewed merely as a means to obtain distributive justice in China (Reference Bodde and MorrisBodde and Morris 1967; Ch'ü 1961). As opposed to the formalism of Western litigation, Chinese civil trials have traditionally focused on substantive justice. Reference HuangHuang (1996: 226) suggests that Chinese law “never developed the elaborate rules of evidence that characterize the formalist proceduralism of modern Western law,” and that it did not concede the existence of any higher truth arrived at by the procedural parameters set by the court. A fair trial was measured on the basis of whether the judgment was rational and had the appropriate social effect, rather than the extent to which the appropriate procedure had been followed (Reference LiLi 2014: 141). In this sense, the ultimate goal of Chinese traditional civil litigation has been to achieve substantive justice. Little attention has been paid to procedures (Reference Fu, Cullen, Woo and GallagherFu and Cullen 2011).

However, cultural explanations are inadequate, since they cannot explain why attitudes are rapidly changing. As Reference GallagherGallagher (2006, Reference Gallagher2017) demonstrates, with more legal experiences and knowledge, migrant laborers gain more respect for the process. However, Feng and He (2018) contend that with more experience in the petition system, petitioners become more concerned with outcomes. Legal consciousness is thus not static, nor is it tracking social, cultural, and economic developments in a linear fashion. Rather, justice is situated in context: the setting of each group, as well as the timing of a given study, makes a difference (Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012).

In this study, we interviewed 142 litigants in divorce, contract, labor, and tort cases in a district court in Southern China. To our knowledge, this was the first attempt to systematically evaluate the theory of procedural justice in China by interviewing litigants who had experienced courts. In face-to-face interviews with those who have experienced the civil justice system in China, we inquired about their litigation experiences and explored the role of procedural justice in their impressions of the court.

Contrary to the common finding that procedural justice is essential in litigants' assessment of civil justice, but consistent with what has been found in several existing studies from China, we find that procedural justice plays a minimal role. Their perceptions of justice are overwhelmingly determined by distributive justice, or whether they get a favorable outcome; in many cases, the outcome determines distributive justice. When the outcome is unexpected, they infer that the process is unfair. Indeed, in our interviews, they often gave little attention to procedural justice.

We argue that unfamiliarity with the law and the operation of court proceedings is a crucial reason for the minimum role of procedural justice. If Chinese people, like people in other jurisdictions, are generally unfamiliar with the operations of the court, Chinese courts' recent switch from inquisitorial adjudications toward more adversarial processes only complicates the situation. China's judicial systems have undergone frequent institutional and professional reforms, some of which are inconsistent with traditional, ingrained perceptions of justice. Litigants, when involuntarily drawn into legal battles, lack understanding of the law and the function of the courts. Due to their unfamiliarity, many cannot distinguish between procedural justice and outcomes, nor do they feel any control over the process. Moreover, they are dissatisfied with the process simply because it fails to conform to their often-erroneous expectations.

We do not claim that our findings and explanations are generalizable to other settings or other periods of China's legal reforms. Nor do we argue that procedural justice is unimportant to Chinese litigants. But our findings do provide another piece of evidence that China may be different, as far as the dominance of procedural justice is concerned. Our focus on Chinese litigants' perceptions of justice serves a cautionary note against over-overgeneralization. Our findings reinforce the discovery that specific contextual elements, such as traditional Chinese legal culture, newly introduced adversarial adjudicatory process, a lack of legal representation, and westernized evidence rules, are important in shaping perceptions of justice. We hope that some aspects found in this Chinese case study, such as the gap between lay understanding and the reality of the legal system, as shown in other works from the legal anthropology tradition (Reference Engel and EngelEngel and Engel 2010; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1998; Reference MerryMerry 1990; Reference NielsonNielson 2000; Reference O'Barr and ConleyO'Barr and Conley 1988; Reference SaratSarat 1990), may provide a basis for further inquiries into the relationship between social and institutional contexts, and the perception of justice.

The remainder of the article first reviews the literature on the role of court experiences in perceptions of procedural justice. Then, we explain China's civil justice system, which has been in constant flux during the reform periods. After setting the backdrop, we provide an overview of the research site, data, and methods of analysis. Next, we turn to our findings and analysis. Throughout our analysis, we highlight how experiences, and especially unfamiliarity, shape litigants' evaluations of China's civil justice system.

1. Procedural Justice and Court Experience

The study of procedural justice originated in experimental research in social psychology investigating the influence of decision evaluation on outcome acceptance (Reference Thibaut, Friedland and WalkerThibaut et al. 1974). Outcome refers to the favorability of a decision (Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988: 1)Footnote 1, while distributive justice refers to whether a distribution of outcomes is appropriate or fair. The former is objective but the latter is subjective. Procedural justice refers to whether the process and manner of the decisionmaking is fair (Reference Leventhal, Gergen, Greenberg and WillisLeventhal 1980: 30). Reference Thibaut and WalkerThibaut and Walker (1975) have argued that perceptions of procedural justice affect satisfaction of the overall process, regardless of the level or fairness of the outcomes obtained. Of course, no one likes to lose, but people cannot always win when they are in conflict with others. They accept “losing” more willingly if they believe the court procedures used to handle their cases are fair.

Subsequent studies have argued that procedural justice is more powerful in influencing social attitudes than are outcome and distributive justice (Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988). In his study on people who had experienced traffic and misdemeanor courts, Reference TylerTyler (1984: 71) finds that “since outcome level appears to explain a relatively small portion of the variance in fairness, other determinants of fairness, many of which are procedural, appear to play the major role in explaining the attitudes of traffic violators and other petty offenders toward the legal system.” In a survey study, Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo (2002) suggest that the primary factor shaping the willingness to accept decisions is the perceived fairness of court procedures. It is also the primary factor shaping the influence of personal experience upon overall views of the court system. A recent study also has affirmed the linkage between procedural justice and evaluations of the courts (Reference Rottman, Bornstein and TomkinsRottman 2015). Reference Tyler, Callahan and FrostTyler (2007: 31) asserts, “The willingness to accept court decisions, in other words, was about the procedures used to reach those decisions, not the decisions themselves.”

Researchers have identified the elements, or dimensions, used to evaluate procedural fairness. The first is process control. If a procedure offers adequate opportunities for people to present their evidence and opinions, it will be viewed as fair. How process control works in enhancing litigants' satisfaction is independent of the control over the decision. The satisfaction with outcome can be enhanced merely by the opportunity of expression. This is why Reference Thibaut and WalkerThibaut and Walker (1975) found that people in the adversary procedure were more satisfied with verdicts than those in the inquisitorial procedure. The second is dignity. The more a procedure offers dignified treatment, the more likely users will perceive it as fair. The third is neutrality. If a procedure appears to be biased, it will be seen as unjust. Neutrality matters, because it is viewed “as a concern in and of itself” (Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler and Allan Lind 1992: 142). A neutral authority creates a “level playing field by engaging in even-handed treatment of all involved” (Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler and Allan Lind 1992: 141). Neutrality involves honesty and equal treatment. The last is trustworthiness, referring to a person's belief that the authorities will try to behave fairly. As with other elements, the key in concerns about trustworthiness “has to do with qualities of the authority and the perceiver-authority relationship, not with the effects of the authority's decision on factors external to the procedural experience” (Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler and Allan Lind 1992: 142).

Each of these concepts suggests that experience matters in evaluating court process. One's perception should be different after she experiences the process because the experience will inform her judgment on process control and other measurements. In Reference O'Barr and ConleyO'Barr and Conley's (1988) ethnography, the background, and especially the prior experience, with the civil justice system made a difference in small claims litigants' evaluations of the process. Reference Kritzer and VoelkerKritzer and Voelker (1998) ask whether “familiarity breeds respect?” While they do not use the term “procedural justice,” “respect” overlaps with procedural justice. Due to negative experience with welfare laws and the tortuous bureaucracy, the downtrodden believe that “the law is all over” (Reference SaratSarat 1990). In Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey's (1998) classic categorization of legal consciousness, “before the law” and “against the law” characterize those who have little experience with the law, while “with the law” is more experiential. Reference Benesh and HowellBenesh and Howell (2001) reinforce that “experience matters,” and argue that different experiences produce different results: those with more stakes but less control are the least confident, and vice versa. In particular, procedural justice looms larger for lower courts than for the US Supreme Court because people can experience the former, while most only read about the latter. Procedural considerations like courteous treatment and timeliness become important because they impact daily life. If users are unfamiliar with the process of a legal service, they may prioritize outcomes. Examining the users of ombuds services, Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt and Bradford (2016: 1011) found that “If people are unsure about what to expect from a process, the perceived fairness of the outcome has larger weight in their assessments of the fairness of the process.” Reference van den Bos, Vermunt and Wilkevan den Bos et al. (1997) also found that “what is fair depends more on what comes first than on what comes next”: the information received first is crucial. Under their rationale, the experience of obtaining different information is also important. The unfamiliar procedure in the decision-making process prevents litigants' from appreciating the value of procedural justice. “Against the law,” as coined by Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey (1998), represents the perception of law from the underclass who knows little about its content and operation.

In the context of China, experience also plays a decisive role in influencing evaluations of the law and the courts. Reference Michelson, Read, Woo and GallagherMichelson and Read (2011) argue that positive popular sentiment is concentrated among people either with no experience or with positive experience in the legal system. Their own survey finds that the perceptions of users are worse than the perceptions of nonusers. Experience also factors into Gallagher's pathbreaking studies. Before filing a complaint, migrant laborers had only held a vague, yet positive, sense of the law, and knew little about how it worked. Some held erroneous understandings of the system (Reference GallagherGallagher 2006; Reference Gallagher, Wang, Woo and GallagherGallagher and Wang 2011). Subsequently, their first legal encounter led to disillusionment and negative perceptions of the system. However, as they gained experience in the legal setting, they became disenchanted, forming a less negative, yet more realistic, view. In Gallagher's words, “personal efficacy” and knowledge of the law could mitigate the disillusionment, even if “the law is more flawed than first believed.” On the contrary, internal migrant workers, lacking both experience and knowledge about the “legal labyrinth,” are only confused and frustrated by the system (Reference LeeLee 2007). Some find themselves “beneath the law” (Reference He, Wang and YangHe et al. 2013), and eventually turn the streets into the courtroom (Reference Su and HeSu and He 2010), resorting to extra-legal methods to resolve their disputes.

2. The Chinese Civil Justice System in Constant Flux

Over the last two decades, China's civil justice system, as an integral part of its legal reforms, has undergone constant change. Since the mid-1990s, several adjudication reforms have been launched. In 2019, the SPC promulgated the fifth five-year reform measure (SPC 2019). The contents of these reforms have covered topics such as adjudicating modes, the assessor's system, the court budgeting system, the setup of the circuit courts, and the formalities of hearings. As a response to the market economy and the growing volume of civil disputes arising from increased economic and social activities, civil procedures have been strengthened. The Civil Procedural Law, the PRC's first civil procedure code, was enacted in 1982. It was revised in 1991 to incorporate procedural reforms. Civil trials have since been opened to the public, formal hearings have become compulsory, and party autonomy has been encouraged.

One of the most noticeable reforms has been shifting the burden of evidence from judges to litigants. The Civil Procedural Law (Art. 64) stipulates that the major task of the courts is to review evidence presented by the litigation parties, and that they are only to collect evidence when necessary. The newly added Article 65 in the Law's 2012 amendment further states that litigants must submit evidence in a timely matter. Under this new system, traditionally inquisitorial judges retreat to the backseat. Judges are now required to act as a neutral third party, applying the law impartially, and as a passive arbitrator, allowing the litigants to play more active and assertive roles. Moreover, the SPC enacted the Evidence Rules in 2003, detailing the rules on evidence discovery, time limits for evidence submission, and the persuasiveness of evidence. The time limit has been particularly controversial. Borrowed from Western litigation rules, it stipulates that evidence produced after a time limit is inadmissible.

As to procedural justice, the recusal institution has been strengthened to secure neutrality (Art. 198.7, Civil Procedural Law 2012), as has the right to voice (Art. 9). Process control is emphasized in the right to debate and present evidence. Even for mediation, a traditional mode of Chinese civil justice, the Civil Procedural Law (Art. 93) stipulates that mediation requires litigants' consent (process control), and that the settlement cannot be coercive (neutrality, Art. 96).

On the books, Chinese procedural laws have thus moved away from the civil-law inquisitorial tradition and toward a more adversarial model: the policy buzzword in Chinese courts is now “litigantism” (当事人主义) (Reference Zhang and ZwierZhang and Zwier 2002–2003; Reference Zhong and YuZhong and Yu 2004). In civil actions, litigants are now required to provide written evidence and to share it with the opposition in the pretrial stage. During the trial, the plaintiff and the defendant each present their evidence, and each side is permitted to respond.

Out-of-court investigations have become less common, as judges rely on a limited form of cross-examination to obtain oral testimony that can be used to justify a decision. This judge-initiated questioning becomes an inexpensive substitute for the previously labor-intensive court investigation. Nonetheless, Chinese judges continue to assume a central role in managing civil trials. Despite reforms toward a more adversarial format, judges retain much of the power to direct and manage the trial process, from beginning to end. Yet, they are working within the framework of a new procedural law that emphasizes formal openness and litigation rights. As documented by Reference He and NgHe and Ng 2013: 7), from the beginning to the end of a trial, the judge is firmly in charge. “He or she coordinates with all the parties, raises questions, and controls the tempo of the trial. In most situations, other judges or lay assessors rarely speak up. The significance of the interaction with the judge becomes more apparent in the mediation stage. It is here that the judge strives to convince parties to accept a deal. The judge can ask one party to temporarily leave the courtroom in order to caucus with the other party.” Because of this dominant power, the judge acts as “the third party” (Reference PhilipsPhilips 1990) and is probably the most important party in the trial.

Many litigants are not represented. Some are represented by friends and relatives, basic-level legal service workers referred to as citizen representatives. Their understanding of the judicial process is not necessarily better than that of the litigants. In some cases, there are lawyers for only one party. Even for cases in which litigants are represented by lawyers, the role of the lawyer remains more advisory than adversarial. Despite the newfound emphasis on in-trial proof taking, the primary role of Chinese lawyers is to act as spokespersons and advisors for the clients they represent. This marginal role of lawyers is tied to the lack of legal professionalism, but is also related to the dominant role of the judges.

Most litigants are new to the legal process, or to use Reference GalanterGalanter's (1974) term, they are “one-shotters.” These civil litigants, both plaintiffs and defendants, are involuntarily dragged into the legal process. The system's frequent reforms only complicate matters: most litigants are familiar with neither the law, nor court procedures, including the roles of the judge and of themselves as litigants. For example, Reference He and NgHe and Ng (2013: 298) in their study of the operation of the civil procedure state, “While women plaintiffs often raise the issue of domestic violence during the court investigation stage of a trial, the first problem facing these women is that they do not know how to, as it were, produce evidence and give testimony in court. Many are still unrepresented. Even when represented, they usually lack the required documents (police reports, medical records, or their own written statements made at the time of abuse) necessary for purposes of the law.” In a word, this group of litigants can be characterized by unfamiliarity with the law and the courts.

3. Data and Methods

The data and analysis presented in this study are based on thirteen weeks of fieldwork investigation in City S, in Southern China, in the fall of 2015. Located in one of the most affluent regions of China, City S's gross domestic product per capita had reached 20,000 USD by 2015, one of the highest in China. This high average income attracts high-quality legal professionals. Court S, the district court where we conducted our fieldwork, employed 80 judges, plus administrative staff. Each of the judges held bachelor's or higher degrees. As the frontier of China's legal reforms, the court had implemented the open trial, formal proceedings, evidence rules, and the adversarial style of adjudication. Judges are required by the law to respect the procedures.

We chose a district court to conduct our fieldwork investigations because at this level, the court has its most direct contact with ordinary people. It affects citizens' lives every day, and those affected citizens are aware that the court is responsible for its actions. The mundane matters adjudicated at this level, coupled with the concrete wins and losses incurred, constitute an ideal site to study the relationship between experience and litigants' evaluation of the court process.

Accessing the court through a personal connection, we were allowed to interview litigants directly. According to a policy intended for civil trials (SPC 1998), there are four stages in a Chinese court hearing: court investigation, court discussion, court mediation, and decision announcement. The decision is usually announced several days or weeks after the hearing is adjourned. After being notified by the court, most litigants visit the court to collect their judgments. Thus, this was our best opportunity to approach litigants, since it could have been their last visit to the court. By this method, we also excluded those cases settled: the settled cases got their settlement decisions directly from the judge; the settled cases do not have a judgment to collect.Footnote 2

We selected four types of civil cases—torts, divorces, contracts (including property letting and conveyance), and labor cases, since these represent the bulk of civil cases handled by basic-level courts in China. Since our interest lay in the attitudes of individual rather than corporate litigants, our sample included only cases in which at least one party was an individual. Government and corporate litigants were excluded because previous studies have indicated that institutional litigants' concerns differ from those of individual litigants (Reference Lind, MacCoun, Ebener, Felstiner, Hensler, Resnik and TylerLind et al. 1989). In addition, our sample only consisted of individual litigants who had appeared in proceedings. If a litigant had entrusted the case to a lawyer and was absent from the proceeding, that litigant lacked the first-hand court experience that we expected.

Since litigants, upon receiving the judgments, often had questions about them for the court staff, we waited until they had finished their questions, and had processed their judgments. Before they left the court, we invited them to participate in our research. This method ensured that each litigant had an equal likelihood of being selected. In total, 243 litigants met our conditions. We interviewed litigants in a room provided by the court. One hundred forty-two completed the questionnaire, for a response rate of 58%. This is high, compared with 37% in Reference Ohbuchi, Teshigahara, Sugawara and ImazaiOhbuchi et al. (2005) and 48% in Reference Lind, MacCoun, Ebener, Felstiner, Hensler, Resnik and TylerLind et al. (1989). One hundred five litigants also consented to our in-depth interview on their evaluation of the court and the legal system. On average, each interview lasted about sixty minutes.

Of the 142 respondents, 66% were plaintiffs; 30% were involved in contract litigation; 27% with tort litigation; 25% with divorce litigation; and 18% with labor litigation. In addition, 48% of respondents had an associate's (大专) degree or above, and 33% earned between 5,000 and 10,000 yuan per month; 45% earned less than 5,000 yuan, and 22% earned more than 10,000 yuan. Of these, 66% were male and 34% were female. Only a minority (35%) were represented by a lawyer. For 110 (78%), it was their first legal battle. Twenty-nine (20.4%) were handled with the Ordinary Procedure, while the rest were handled with the Simplified Procedure. While most spoke Mandarin, 20% had thick accents, struggling to express themselves by peppering their speech with Cantonese dialects.

3.1 In-Depth Interviews

We opened the interviews with casual topics such as the origin of their disputes, or by answering their questions about the judgments. We also emphasized our role as researchers. In order to mitigate any possible influence of the court, we promised interviewees that all information would remain confidential. Moreover, we conducted interviews behind closed doors. It appeared as if we had earned the trust of most litigants, as some were willing to consult us on legal issues and share their stories.

After explaining who we were and our purposes, we moved to the question, “What is your case about?” The interviews were semi-structured, but we also encouraged litigants to talk freely on any topic. This proved productive, as the litigants discussed the details of their cases, often providing elaborate versions of “what happened” as the interviews progressed. In addition, they talked about their general views of the legal process, of the judge, of the legal rules, of their burden of proof in court, and of what they would use as evidence. We inquired specifically about the aspects about which they felt the least satisfied.

None of the interviews were taped. Instead, we took notes in about one third of the interviews. In instances when note taking made the interviewees nervous and disrupted the natural flow of conversation, we memorized important details and recorded them in notebooks as soon after the interview as possible.

3.2 Surveys

After discussing their cases and views, we invited them to take a survey. Discussing with them before the survey is because the discussions not only helped them understand the role of us as researchers, but also offered them more time to process their experience. Our surveys followed the established research tradition on laymen's evaluations of court experiences (e.g., Reference Casper, Tyler and FisherCasper et al. 1988; Reference TylerTyler 1984).

Inspired by Reference Lind, MacCoun, Ebener, Felstiner, Hensler, Resnik and TylerLind et al. (1989) and Reference Ohbuchi, Teshigahara, Sugawara and ImazaiOhbuchi et al. (2005), we employed a single item measure to assess their levels of overall satisfaction: “Do you feel satisfied with the outcome?” Responses were rated on a three-point Likert scale: satisfied, neutral, or dissatisfied.

Our measure of procedural justice was based on what has been employed in previous literature (e.g., Reference Lind, MacCoun, Ebener, Felstiner, Hensler, Resnik and TylerLind et al. 1990; Reference Lind and TylerLind and Tyler 1988; Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003). We asked interviewees to evaluate whether the judge had “treated you politely,” “made effort to be fair,” “given you enough opportunity to present evidence and opinions,” “been honest,” “made a decision based on accurate and adequate information about the case,” and “treated both sides equally.” All responses were measured using a four-point Likert scale.

Outcomes were calculated according to the adjudication decisions (He and Yang 2013; Reference He and LinHe and Lin 2017). Civil cases often involved both monetary and nonmonetary claims. For those with monetary claims, we calculated the percentage of the plaintiff's monetary compensation for his or her petition, and then multiplied the percentage by 100. For instance, if a plaintiff had received 30% of his/her claim, the plaintiff's outcome would be coded as thirty, while the defendant's outcome would be seventy. Zero indicated that the plaintiff had lost the case, while hundred indicated that the plaintiff had a full win; and vice versa for the defendant. The higher the number, the more successful the lawsuit had been for the litigant.

For cases involving nonmonetary claims, we relied on the litigation fee share (LFS) to measure outcomes. According to the Measure on Litigation Fees (the State Council 2006) in China, the losing party must bear the full litigation fee, and the court has discretion to allocate the fees in situations of partial wins or loses (Art. 29). In practice, the judges we interviewed said that they often “assign litigation fees to each party that reflect the judges' sense of who won the case by how much.” In other words, the LFS reflects the ratio of the portion of the claim dismissed to the portion upheld. Hence, if a plaintiff was required to bear 30% of the litigation fee, his or her outcome would be coded as seventy, while the defendant's outcome would be thirty. However, in some cases in which the litigation fees were fixed or small, judges only asked the stronger party to pay, regardless of the results. Hence, we excluded five missing cases, in which neither method of coding had decided the outcomes. Since whether to grant divorce has been routinized (Reference HeHe 2009), court decisions on divorce itself do not suggest a win or a loss. We thus classified divorce cases into two categories, depending on whether there had been contention over child custody. When the plaintiff had only asked for divorce and property partitions, the outcomes were coded according to the awarded amount; when child custody was also in dispute, in addition to divorce and property partitions, the outcomes were coded according to the LFS. Under Chinese laws, women have a greater chance getting child custody. The decision on this issue is thus not a good measure for winning and losing. Couples often fought fiercely on property division; many interviewees, though being awarded child custody, still felt unsatisfied with the overall litigation process, because they did not get the property that they expected. That is why we used LFS in this type of cases to differentiate winning and losing. None of the cases in our data involved child custody only.

Following the existing literature (e.g., Reference TylerTyler 1988, Reference Tyler1990; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo 2002), distributive justice was measured by two five-point Likert-scale questions: “How fair do you feel the outcome you received from the court was?” and “Did you receive the outcome you deserved?” We also included participants' gender, education background, income, case type, and whether they had been the plaintiff or defendant in our analysis.

4. The Minimal Role of Procedural Justice

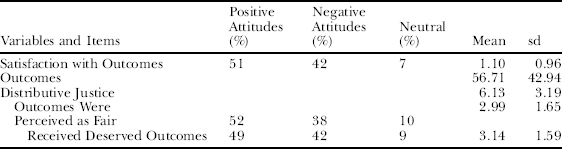

Table 1 shows that 51% of respondents were satisfied with the outcome that they received from the court; 42% were dissatisfied, and 7% were neutral (mean = 1.10, sd = 0.96).

Table 1. Variables Used in the Analysis

The respondents, on average, received 57% of what they had asked for in their lawsuits. Twenty-two percent had lost their cases entirely (outcome = 0), and 36% had won fully (outcome = 100) (mean = 56.71, sd = 42.94). Moreover, the average distributive justice score was 6.13 (sd = 3.19). Fifty-two percent rated the outcomes as fair, 38% rated them as unfair, and 10% regarded them as neutral (mean = 2.99, sd = 1.65). When asked whether they had deserved their outcomes, 49% responded positively, while 42% were negative and 9% were neutral (mean = 3.14, sd = 1.59). The two items were significantly correlated (χ 2[1] = 110.21, p < 0.001), with a strong association (φ = 0.89, p < 0.001).

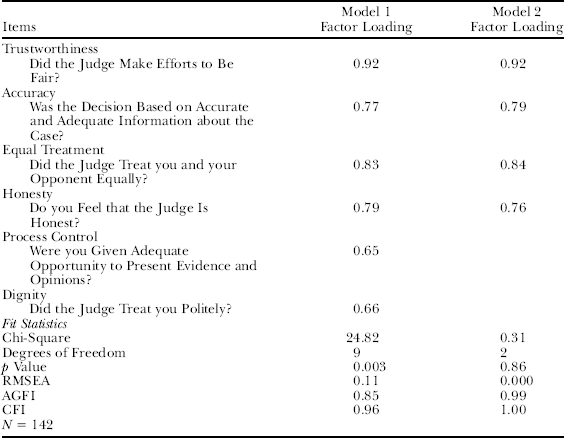

Procedural justice was generated via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Footnote 3 Table 2 shows the full question wordings from the items and the results of the CFA modeling.Footnote 4 As shown in Model 1, the model fitted poorly (χ 2[9] = 24.82, p = 0.003; The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.11)Footnote 5. Moreover, we also observed high-correlation residualsFootnote 6 for dignity and several other indicators (e.g., 0.10 for dignity and honesty; 0.13 for dignity and process control). The correlation residuals for process control and several of the indicators were high as well. Accordingly, we dropped dignity and process control. Then, the new model (Model 2) showed a good fit (χ 2[2] = 0.31, p = 0.86; RMSEA = 0.000), and all the correlation residuals were below 0.02.

Table 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis: The Latent Factor (Procedural Justice) and the Measures

Therefore, we combined the items in Model 2 to create an index. The four dimensions of procedural justice were characterized as inferred, as they each tapped into judges' internal motives and were not from external behaviors. In the following analysis, the summary index is addressed separately from process control and dignity.

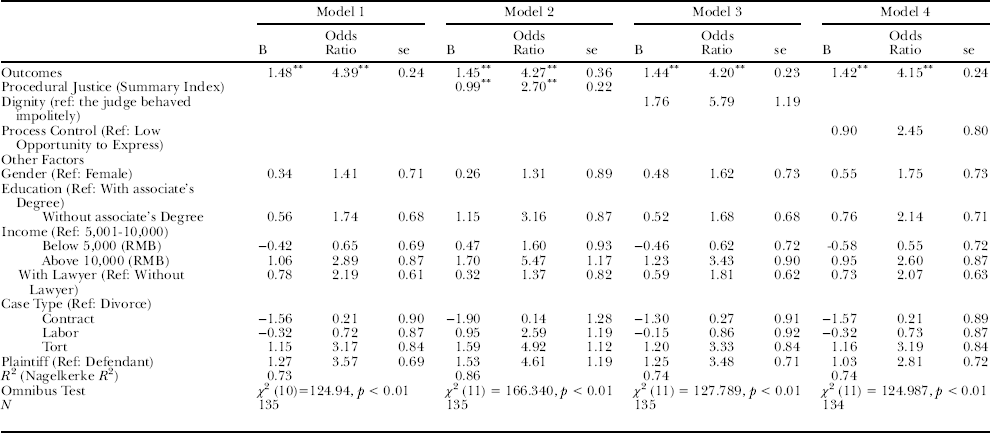

Which factors contributed to the explanation of the rate of respondent satisfaction to outcomes? Table 3 presents the results of ordered logistic regressions.Footnote 7 Whether a respondent had been the plaintiff or defendant had only marginal significance (p = 0.064). Income, education, and gender each had no statistical effect. Whether a respondent had used a lawyer also did not matter. There was a marginally significant difference (p = 0.083) between contract cases and divorce cases.

Table 3. Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Satisfaction with Outcomes

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The outcomesFootnote 8 that respondents received from the courts were statistically important: the more favorable outcomes a respondent obtained from the court, the higher the likelihood of satisfaction. We found a very strong association between outcomes and satisfaction (odds ratio = 4.39, p < 0.01). A clearer idea of the strength of this association can be gained by calculating fitted probabilities. The fitted probability of a respondent obtaining the mean level of outcome for satisfaction was 0.52. For respondents obtaining better outcomes (20% above mean level), the probability of satisfaction rose to 0.77. For respondents obtaining a lower outcome (20% below mean level), the probability of satisfaction decreased to 0.26 (see Figure 1). Outcomes alone predicted 73% (Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.73) of the variation in the dependent variable.Footnote 9

Figure 1. Litigants' Satisfaction with Outcomes as a Function of the Outcomes that they Received from the Court. The X-Axis Represents Outcomes, and the Y-Axis Represents the Fitted Probabilities of Satisfaction with Outcomes.

Model 2 suggested that when considered together, outcomes and procedural justiceFootnote 10 predicted 86% (Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.86) of the variation in respondents' satisfaction with outcomes.Footnote 11 Thus, after controlling for outcomes and the control variables, the unique contribution by procedural justice was 13% (change in Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.13), which was particularly weak. A Sobel test, a method to test the mediation effect, further indicated a statistically significant effect: outcomes played the dominant role, while procedural justice merely acted as a mediator to transmit the effect of outcomes on the dependent variable (Sobel test statistic = 4.729, p < 0.001)Footnote 12.

Findings from Model 3 indicate that after controlling outcomes, dignity exerted no statistically significant impact on the dependent variable: whether the judge behaved politely did not affect the probability of satisfaction. Also, process control showed no statistically significant effect once the other variables in the model had been taken into account (Model 4). Respondents who reported being granted more voice were no more likely to be satisfied with their outcomes.

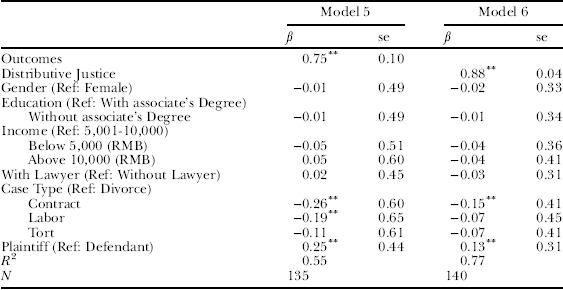

When are procedures experienced as fair? Prior research suggests that outcomes and distributive justice are important in the assessment of procedural justice. To explore this, we estimated a second set of regression models, this time with procedural justice as the dependent variable. Model 5 (Table 4) shows outcomes to be the most important predictor of procedural justice: those who received a more favorable outcome tended to have more favorable perceptions of procedural justice (ß = 0.75, p < 0.001). Note the large R 2 value for this model (0.55): almost half of the variation in perception of procedural justice can be explained by outcomes.Footnote 13

Table 4. Results from Linear Regression Models Predicting Perceptions of Procedural Justice

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Also, we observed a high association between procedural justice and distributive justice (ß = 0.88, p < 0.001, Model 6), suggesting that those obtaining less equitable outcomes tended to view their trials as less procedurally fair. Distributive justice alone explained more than 70% of the variation in satisfaction with outcomes (R 2 = 0.77).

5. Unfamiliarity as an Explanation

Outcomes played a dominant role in shaping assessments of procedural justice: both the respondents' perceptions of procedural justice and their satisfaction with the process depended on the outcomes they had obtained from the court. By contrast, the independent influence of procedural justice was weak: it exerted only a limited effect on satisfaction with outcomes. Of 105 litigants we interviewed, only one rated the whole process “neutral” and two rated it as “positive” despite not getting the desired outcomes.Footnote 14

Our in-depth interviews suggested that litigants' unfamiliarity with the role of the judge and the substantive law constituted a crucial reason for the minimal role of procedural justice.

5.1 The Judge's Role

Most of the litigants believed that the judges should have taken the initiative to investigate the facts, summon witnesses and collect evidence, with litigants playing only a supporting role. Litigants were generally unaware that the burden of proof was on them, and that the judge was merely a neutral and passive arbitrator. Misunderstandings and unrealistic expectations abounded.

Lin, a school teacher fighting for child custody, blamed the judge for failing to “thoroughly” investigate her case and seek out the “truth.” She had insisted that she had raised her son, and had accused her husband of infidelity. She had failed to prove either of these accusations, however. By contrast, the plaintiff had offered evidence, proving that the boy had always lived with his grandparents. Nonetheless, she said:

The judge did not violate the legal procedure (She paused for a few minutes, calming herself). However, I really felt it was unfair, very unfair!…He just followed a formalistic procedure. As you just told me, only in criminal cases are the authorities supposed to take the initiative to investigate. However, we are just ordinary citizens, the weak. We need help!…It is wrong to only care about the cases (she meant the criminal cases) which they think are valuable.

As to why judges are responsible for investigating, Lin's reasoning was, “we are ordinary citizens, and we need help.” In her eyes, being a protector or servant, the judge should have taken the initiative to investigate, collect evidence, and offer guidance and help. However, in contrast to the role of the judge in the inquisitorial system with which Chinese litigants are familiar, the Civil Procedural Law now requires judges to neutrally follow a formal legal procedure and to adjudicate according to admitted evidence. Such a gap had contributed to Lin's disappointment and frustration. Even after her lawyer had explained to her that the judge' passive position was legally appropriate, she still refused to accept the judgment.

This misconception of the judge's role was prevalent among educated men in business disputes. Zhao, a middle-aged businessman with a college degree, had been involved in a contract dispute. In 2004, he had lent 400,000 yuan to the defendant, a small company owned by one of his friends. According to their contract, the company was to pay Zhao 5% interest annually, and return the principal in 2012. However, the company had been postponing the payment since 2012. Zhao had filed a lawsuit against both the company and the two shareholders. He had accused the shareholders of contributing insufficient capital, but failed to offer evidence. The defendants, however, offered a Capital Verification Report, issued by an authorized accounting firm, testifying that the shareholders had contributed sufficient capital to the company. Zhao therefore lost the case. He commented:

In fact, it is the court that should be responsible for collecting the information. The court should find out the truth, (and) make certain that what I said is true…It is easy for the court to get documents from other organizations. An ordinary citizen like me is incapable of getting documents from the Bank (He mistook the Industrial and Commercial Bureau for “the Bank”). So you know why I am reluctant to be involved in a lawsuit. It's because the court is problematic.

Similar to Lin, Zhao believed that the court should collect evidence, and verify his statements. As a result, he distrusted the court because “the court is problematic,” and that was why he was “reluctant to be involved in a lawsuit.”

Unfamiliarity with the changed role of the judges was also common in other types of cases. In a labor case, He, a doorwoman, filed a claim for overtime pay after she had been fired. She said that she had been tricked into backdating a labor contract at the employer's Spring Festival party, but she could not produce evidence of this. Frustrated by the case outcome, she said:

I feel wronged. It seems that I have to swallow my grievances and suffer from injustice…The court is very cold, indifferent, and apathetic…I cannot understand why it is my responsibility to present evidence. The judge should help me if I cannot provide (evidence). I am weak, barely educated, and relegated to the bottom of society. The judge should make certain that I do not lie and that I do not extort the employer. However, the outcome implied that I am a liar.

Similar to Lin and Zhao, He could not figure out “why it is (her) responsibility to provide evidence.” She thus complained that the court was “cold, indifferent, and apathetic.” Each of these complaints on procedure was linked to the reason why they had lost the case, which was why they had been dissatisfied. For those with favorable judgments, they were satisfied with the court process, but with the same mistaken conceptions of the judge's rule. For example, Xiao, the woman who had won the lawsuit against the insurance company, believed that the judge had been a protector and that the court was serving ordinary people like her.

5.2 The Legal Rules

Unfamiliarity with the legal rules is also common. Some litigants are clueless about the procedural rules. Others lack comprehension of the law's contents. Many of their beliefs are drawn from traditional notions of ethics and morality; others invoke what they have seen on TV dramas.

Wang, an undereducated migrant worker, had trouble even at the stage of filing. Unrepresented by a lawyer, he said:

To be honest, the trial is a maze. I am baffled by it. The court clerk said that my filing documents were unqualified and asked me to re-submit. But I always failed to make sense of their requirements. I had to go to the court again and again. Just for the case filing, I submitted my documents seven times.

At the hearing stage, Wang found the situation more confusing. According to the Evidence Rules, he was entitled to apply for the court to collect a piece of key evidence on his behalf, but the application had to be submitted before the hearing. Wang was not aware of such a legal rule. At the hearing, he blamed the judge, “Why don't you ask the defendant to submit this key evidence?” The judge replied, “You did not apply…” This response confused Wang. He complained to us in our interview, “The judge told me that the statute of limitations to present evidence (举证时限) had expired, so I was no longer allowed to apply. What the hell is the ‘statute of limitations’?Footnote 15 Why is it expired? It is so weird…I am a menial laborer (做工的), not a lawyer. I do not know anything about the law….”

For undereducated litigants like Wang, the trial process was a labyrinth. In our interviews, the expressions “I know little about the law” and “I could not make sense of it” appeared frequently. When asked whether the judge had offered her enough opportunity of expression, He, the doorwoman claiming for overtime payments said, in all seriousness, “I spoke only when she (the judge) asked me. I thought I was supposed to keep silent and respond only when the judge asked me questions. If I took initiative in participating in the discussion without prior permission, I would have broken the law. It would have been contempt of court.” When asked where she got this impression, she said, “a drama on TV.” Without pushing further, we assumed that the drama had been about a criminal trial.

Zhang, a construction worker injured in a traffic accident, complained:

The compensation for lost income was rather unfair. I was out of work for 31 days, but the court only awarded me 3,500 yuan. I can earn much more than that, even with my part-time jobs…I can earn at least 250 yuan per day, sometimes 400 or 500. In fact, I have only asked for 5,500 yuan, which is lower than my monthly income…It is hard for me to understand why (the judge) dismissed the personal aide cost. My hands were seriously hurt…so I hired a guy to help me…It is a plain fact! I did not fabricate it [He repeated this several times]. Why does this court always ask for evidence? I often take motorcyclesFootnote 16 to the hospital. How can I have receipts for the transportation fees?

Zhang believed that the court had been unfair. He believed that he could earn at least 5,500 yuan per month and he had been out of work for a month due to the traffic accident. Therefore, he believed he deserved 5,500 yuan for the lost income. However, since Zhang had failed to present any evidence of his monthly wage, the judge had applied the average income for the construction sector, 3,500 yuan, as stipulated by the law: (a) Zhang had been unable to work for one month; (b) but he only earned 3,500, rather than 5,500 yuan. Although we explained the court's rationale to him, Zhang remained angry. The legal rules did not convince him. His ignorance of the legal rules had led to his dissatisfaction.

Liu's story illustrates the confusion between the law and the traditional notion of ethics and morality. A young plumber, he had fought for custody of his four-year-old. He claimed that his wife had committed adultery. In his view, an immoral woman, “illegally”Footnote 17 cohabiting with a lover, stealing and lying, was not qualified to be a guardian. Since the legal decision ignored his arguments, he was angry:

Actually, if she (his wife) had been an upright person, I would have been happy to offer her custody. Why I strive for custody is not to vent anger or to seek revenge, but so that my son can grow up in a healthy environment. Since she is morally unqualified, I am really worried about my son.

Morality was a dominant criterion in Liu's perception of how the case should have been decided. For him, the court was a venue for implementing moral principles and ethics. Morality was a crucial qualification for a guardian. This was linked to whether or not the decision had been reasonable.

5.3 Unfamiliarity Diminishes the Role of Procedural Justice

As shown, the responses of the litigants to our questions revealed Chinese litigants' unfamiliarity with the legal system. This unfamiliarity exists despite that Chinese government has been popularizing legal knowledge for decades. The public messages, mainly composed of propaganda and rhetoric, do little to explain the fine points of legal procedure or the substance of law to the general public. People become lay legal experts only after they have both experienced the legal process and managed to learn the legal knowledge (Reference GallagherGallagher 2006). Chinese judges are required to patiently explain the legal rules and the reasonableness in the judgments (Reference He and NgHe and Ng 2013). While such efforts may clarify some aspects of the litigants' confusion, judges can only explain the rules and the reasoning in an appointment with the litigants after they receive their judgments, and thus cannot address the confusions and misconceptions of the litigants during the hearing. Judges must also maintain their neutrality in this process.

There are four reasons why unfamiliarity explains the minimal role of procedural justice. First, without a basic understanding of judicial process, many litigants misunderstand both their own and judges' roles. They overestimate the initiative that the court will take in the case, and underestimate their own legal burdens in meeting the evidential and procedural requirements under the new adversarial system. Similar misunderstanding is found in the US (Reference O'Barr and ConleyO'Barr and Conley 1988), but Chinese litigants' misunderstanding is greater. Several factors contribute to this: a traditional image of “the parent official (父母官)”—close to the masses, friendly to the litigants, patient and active in ensuring the litigation parties' interests; the decades-long practice of an inquisitorial system after the founding of the People's Republic; the newness and unfamiliarity of the adversarial system; and a lack of channel informing the general public about what to expect beyond that offered in government propaganda.

These misunderstandings render case outcomes as the most significant factor shaping litigants' assessment of the performance of the judge, including procedural justice. Xiao, an accountant in her early forties, sued a man who rear-ended her car and his insurance company. The issue was whether the insurance company would compensate her repair cost in a private garage. Xiao won the case. She felt satisfied with the justice of the litigation process. She said:

The representative of the Insurance Company still insisted that I cannot repair my car in a private shop. I want to retort him but unable to figure out an effective way. While I was anxious, I heard the judge saying to the defendant: “If you insist that the charge is unreasonable, you should present evidence to prove it. Do you have any evidence?” The defendant replied: “No. We do not have evidence” [laughing]. At that moment, I felt very grateful for the judge, who defeated my opponent.

Xiao perceived the trial procedure as fair. But her assessment was heavily relied on the judge's remarks. The judge's remark that “if you insist that the charge is unreasonable, you should present evidence to prove it” is just an impersonal repetition of the Chinese Evidence Law. In practice, judges often express similar remarks at the stage of court investigation to remind litigants of their burden of proof. Hardly can one draw a conclusion that the judge intentionally favored Xiao.

Xiao's attribution of the outcome to the judge is evidence that she does not understand whether or not the statement of the judge is neutral. Her assessment on the justice process, including procedural justice, derived predominately from the outcome that she had won the case. Indeed, our other cases indicate that winners rarely complain about the procedural problems of the courts or the judges. One winner said, the judge seemed professional, just like what I saw on a movie. Another said, “the courts have been doing well, delivering all the documents in time and the staff was very patient.”

Second, misunderstanding led to mistrust between litigants and judges. When trust is low, litigants rely more on the outcome for assessing the court performance. As recounted in the stories of Lin and Zhao, the litigants believed that the judges were not gathering the facts that were important for their accounts; they believed that the judges do not take their cases seriously. With higher, but often-erroneous expectations, they blamed the judges for failing to do their jobs; the judges' passive and neutral manner, as required by the reformed laws, was interpreted as indifference to litigants' interests. When they receive an unfavorable outcome, they are confused and frustrated. It is easy to blame judges whom they believe to be unprofessional and dishonest, merely going through a formalistic process, ignoring the fundamental goal of pursuing justice. Some suspect that the judges are involved in corruption or guanxi, intentionally favoring their opponents. Thus, the process itself is not trustworthy. When litigants receive a favorable outcome, they are complacent, praising the judges for doing a good job. To them, a favorable outcome is an unambiguous indication that the judge does not favor their opponents. Satisfied with distributive justice, they then have no reason to question the judge's trustworthiness or honesty.

Conceptions of procedural justice are thus linked to outcome-related concerns. Lin, the lady who lost child custody to her husband who had provided evidence that the child had lived primarily with the parental grandparents, said:

I think the judge was unfair. The defendant is a guy with no job or income, but the judge awarded him custody. I am wondering whether the child is mine or his (her husband's) parents'! This outcome actually awarded the child to his parents. Absurd!…Had the judge tried to be fair, the outcome would have been different. In light of this outcome, I speculate that he (her husband) saibaofu (塞包袱, or bribed the judge). You know, he (her husband) is a local citizen, while I am from another province.

She felt collusion between judges and the powerful could be taken for granted, merely because her husband was a local. Unfamiliar with the operation of the court, she allowed herself to associate the negative outcome with speculations. With her increasing mistrust toward the judge, her respect for the judge and her evaluation of procedural justice decreased.

Third, unfamiliarity also makes it difficult for litigants to understand the role and function of procedural justice. Sometimes they cannot even distinguish procedural justice from distributive justice. As demonstrated in He's story, she mistook an interception of conversation as contempt of court. Without understanding what procedural justice is, litigants cannot appreciate the opportunity to be heard provided by the judges. How can they value the respect with which the judges treat them? The theory of procedural justice, as Reference Tyler, Callahan and FrostTyler et al. (2007: 468) states, is conditioned on “people's procedural justice judgements are distinct from their instrumental concerns.” (emphasis added).

Similar to what has been found by Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt and Bradford (2016: 1011), when people are unsure about what to expect from a process, the outcomes weigh heavier in their assessments of procedural justice. Under these circumstances, being interrupted by the judges is unimportant, as long as the outcome is favorable. If Reference van den Bos, Vermunt and Wilkevan den Bos et al. (1997) are right that fairness depends on what information is received first, then outcome-related factors weigh heavier in their assessment of procedural justice, since the outcome is the only visible information. Furthermore, in cases such as losing child custody, there is a high stakes outcome. As demonstrated, high stakes make “outcomes” dominant in evaluating the process (Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012; Reference Heinz and TalaricoHeinz 1985; Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita 2018). Outcomes with higher stakes are more visible and their weight is heavier. On the contrary, a litigant caring little about the outcome may hold a positive view of the litigation process despite losing the case. A lady who just wanted to vent her grievances by filing the lawsuit. “The young defendant refused to apologize after hitting my car, which irritated me,” she said. Receiving only 5% of what she asked for did not prevent her from having a positive view of the litigation.

Unfamiliarity with the decision-making process prevents litigants' from appreciating the value of procedural justice. When the elements constituting procedural justice are less visible, only the outcome is clear and salient to them. This point is corroborated by the association between procedural justice and distributive justice and outcomes: it is higher for invisible dimensions (e.g., trustworthiness or honesty) than for visible dimensions (voice and dignity). As the invisible dimensions tap into judges' motives, which are difficult to infer from their behavior, the litigants are more likely to rely on outcomes or distributive justice to assess them. We conducted a series of Spearman correlation analyses and found that the correlation between trustworthiness and outcomes (0.62, p < 0.01) was stronger than that between process control and outcomes (0.31, p < 0.01), and that between dignity and outcomes (0.33, p < 0.01). Moreover, the association between trustworthiness and distributive justice (0.81, p < 0.01) was almost double that of the association between process control and distributive justice (0.50, p < 0.1) and that between dignity and distributive justice (0.51, p < 0.01). Similar differences were also observed between other invisible dimensions and dignity/process control.

Finally, unfamiliar with the process, litigants rarely felt in control, an important element of procedural justice. As Wang's experience shows, without knowing what documents to submit for case filing, he had to submit the documents seven times. Being repeatedly unable to start his case, how could he feel any control over the process? Having difficulty understanding the statute of limitations, he did not know when to submit evidence. In Zhang's story, he does not understand why evidence of transportation fees is needed and what kind of evidence must be submitted. Thus, how could he feel any control over the process? In Liu's case, he believed that the law should be on his side because his wife had been immoral. Yet, he did not understand that the judge was not concerned with moral issues. How could he feel any control over the process?

Qian's story corroborates the importance of unfamiliarity in shaping evaluations. A company manager in his forties seeking his first divorce, Qian had hired an experienced and expensive lawyer who provided detailed explanations of how the court operated. When the judge dismissed his petition, which was routine in the court's divorce practice (Reference HeHe 2009; Reference He2021; Reference MichelsonMichelson 2019), Qian accepted the judgment. The unfavorable outcomes did not lead to a negative judgment of the judge and the court, “The whole process was consistent with my expectations, so the result does not surprise me. Actually, my lawyer has informed me that for first-time petitions, judges routinely rule against divorce.” Qian was also worried that the female judge would favor his wife because they were both women. However, the lawyer told him that the judge had no intention of doing so. When asked about the judge's fairness, Qian responded, “I think my lawyer is right. The judge is fair. At the hearing, the defendant's lawyer kept questioning me as to whether I had had an extra-marital affair. The judge interrupted him: ‘Even if he had had an extra-marital affair, he would not have confessed.’ [laughed] The judge is sensible. She explicitly pointed out that his (the defendant's lawyer's) effort was useless. You see. While she was female, she had not favored the other party.”

The lawyer's clarification, or Qian's familiarity with trial process, and Qian's background as a businessman, afforded him a reasonable understanding of the civil justice system. In particular, it helped him distinguish procedural justice from outcomes. Thus, he was satisfied with the opportunity to have his voice heard by the court:

I have told the judge all my opinions and presented all the evidence prepared by my lawyer. I even refuted the opposing lawyer's accusations. The lawyer did me a great favor. He taught me how to express myself and how to behave. He asked me to say as little as possible…In short, I have reported (to the judge) all that I should have.

Qian's favorable perception also stemmed from his control over the process. With the lawyer's help, he had understood what he should express and submit. The litigation was no longer a labyrinth. Instead, it became a game. Thus, when he assessed procedural justice, the role of outcome diminished. This pattern also held true for two other divorce petitioners who were told by their friends that the first divorce petition was often denied.

Both our quantitative and qualitative data consistently suggest that unfamiliarity with the court and the law decreases the relative importance of procedural justice. Comparing those represented by lawyers with those unpresented, there is a difference in the role of procedural justice. For those unrepresented, presumably they are less cognizant of the law and the process because they could not learn from their lawyers. For them, the statistically significant association between outcomes and procedural justice was stronger than for those represented (0.73, compared to 0.57)Footnote 18. So was the statistically significant association between outcomes and satisfaction with outcome (0.84, compared to 0.74). For those represented, outcomes weighed less, but the pattern is not statistically definite.

6. Conclusions

Based on surveys and in-depth interviews from a court in Southern China, this study has examined litigants' attitudes toward civil justice and explored the extent to which the theory of procedural justice is applicable in China. While lay people come to court with varying expectations about the civil justice system, the unifying theme is consistent. Contrary to the common view that procedural justice independently shapes users' views of the legal system, our study finds its role minimal in Chinese litigants' responses. Their views are dominated by distributive justice. We argue that litigants' unfamiliarity with the law and the operations of the court is a crucial and immediate cause. The litigants, when involuntarily dragged into legal battles, possess little comprehension of the civil justice system, which has undergone frequent Westernizing reforms. “Familiarity may breed respect” (Reference Kritzer and VoelkerKritzer and Voelker 1998), but unfamiliarity makes it difficult for the litigants to judge the process. The outcome, or distributive justice, becomes apparent and serves as the dominant barometer for their evaluation.

While this study does not directly challenge the validity of the theory of procedural justice, it does provide another piece of evidence that in China, distributive justice may be more important than procedural justice and the two are difficult to distinguish, as found in Reference Gallagher, Wang, Woo and GallagherGallagher and Wang (2011), Reference GallagherGallagher (2017), Reference Feng and CaoFeng and Cao (2014), and Reference Michelson, Read, Woo and GallagherMichelson and Read (2011). More important, going beyond these existing studies, we provide a novel explanation—unfamiliarity—to make sense of why this China case may be an exception from the prevailing procedural justice theory. Unfamiliarity brings about unrealistic expectation, mistaken understanding of the judge's role, and failure to distinguish procedural justice from substantive justice. Previous studies have mentioned that unfamiliarity may affect the role of procedural justice, but the findings came either from experiments (Reference van den Bos, Vermunt and Wilkevan den Bos et al. 1997) or Ombuds Services (Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt and Bradford 2016), which, compared with the court or police, are rarely encountered by the general public. We suggest that in the context of China, with its rapid pace of legal and social changes, unfamiliarity significantly shapes litigants' attitudes toward the frequently encountered court, the most common and important dispute resolution institution. Our study reinforces the importance context for shaping litigants' evaluation of civil justice.

The unfamiliarity explanation does not suggest that Chinese litigants' view of the legal system will definitely be in line with that of the rest of the world once they become more familiar. As our data show, in the cases represented by lawyers, the litigants' ability to differentiate procedural and substantive justice does increase, but not to a level of statistical significance. Some of their beliefs, such as those about the role of the judges, are related to the traditional Chinese culture. Determining whether Chinese cultural elements determine the minor role of procedural justice, or China is an exception to the theory of procedural justice, requires further studies. This study offers an aperture and forms a basis for this line of inquiries.

This article also confirms a discontinuity between lay culture and the legal system, as found elsewhere (Reference MerryMerry 1990; Reference O'Barr and ConleyO'Barr and Conley 1988). Misconceptions about the legal system are pervasive. Lay conceptions of the system deviate from the realities of the legal process as they are practiced in the basic-level court. Most litigants' have limited understanding of the operations of the court and the rules surrounding evidence. This may also be why procedural justice means little to them since they do not know how to utilize these opportunities. Examining the reactions and attitudes of consumers of justice, this article sheds light on the disparity between the different ways that lay and legally trained people conceptualize disputes in China (Reference BoittinBoittin 2013; Reference GallagherGallagher 2006). The differences in reasoning and communication between lay and legal cultures should be of interest to those who study the cultural background of law, as well as those who seek reform of the legal process.

Future studies in different regions of China are needed to verify these findings. Reference Michelson, Read, Woo and GallagherMichelson and Read (2011: 195) argue that it is in the most developed parts of China where the courts deliver the most satisfaction. Given that Southern China has pioneered legal reforms, is the wealthiest region of China, and is also the most exposed to the Western culture, it is conceivable that the significance of procedural justice may be less in China's other regions. For example, Reference PiaPia (2016) suggests that in Yunnan, a hinterland area of Southwestern China, “people follow reason instead of law.” Also worth noting is that our research was conducted at a time when the regime had been promoting the rule of law and was strengthening the legal consciousness of the general public. In short, if at the time of our study, Court S had been somehow less than typical, our findings would have been even more pronounced in other regions, or at other moments in China's history.

Our findings not only uncover the sources of dissatisfaction among litigants, but also raise important questions about confidence in the courts. What can the authorities do to increase satisfaction? Chinese authorities are supposed to not only promote procedural reforms, but also inculcate the values of procedural justice when evaluating the performance of the legal system. They are supposed to not only explain the rationale after a decision has been made (the current practice), but also to communicate to the litigants the importance of procedure and evidence, before the court proceedings begin. Research on the US suggests that informed consent is one major reason for not suing for medical malpractice (Brodsky et al. 2004). Once the litigants understand more of the procedures, or become more familiar with the system, they may appreciate the value of procedural justice.

The gap between the court's application of the law and litigants' legal consciousness is not unique to China. In Reference MerryMerry's (1990) classic research on the legal consciousness of the working class in the US, she also documents such a gap and litigants' frustration. Reference O'Barr and ConleyO'Barr and Conley's (1988: 137) investigation of litigant perceptions of justice in the US finds that despite their unfamiliarity and misconceptions about the purely adversarial nature of the proceedings, litigants are still “at least as concerned with issues of process as they are with the substantive questions.” Yet, the extent of the gap seems far larger in China. American litigants did not believe that the court could have violated the law, and their frustration did not challenge to the legitimacy of the legal system. In China, however, the courts and judges enjoyed little authority (Reference Ng and HeNg and He 2017). In the eyes of the general public, corruption and guanxi are rampant (Reference He and NgHe and Ng 2017; Reference LiLi 2012). The level of trust of the judges and the courts seems much lower. While the state has made mobilized its people to use the law, these efforts rarely inform people about detailed procedures (Reference GallagherGallagher 2006) or procedural justice. Even the courts and the judges do not fully obey the procedural requirements (Reference Woo and WangWoo and Wang 2005). All these factors, combined with the constant reforms largely imported from the Western countries, reduce procedural fairness to petty evenhandedness. The parties with unfavorable outcomes were rarely satisfied with their court experiences. Often they conclude that corruption led to their unfavorable judgments. Strengthening legitimacy and authority is thus vital for China's judicial and legal reforms.