Introduction

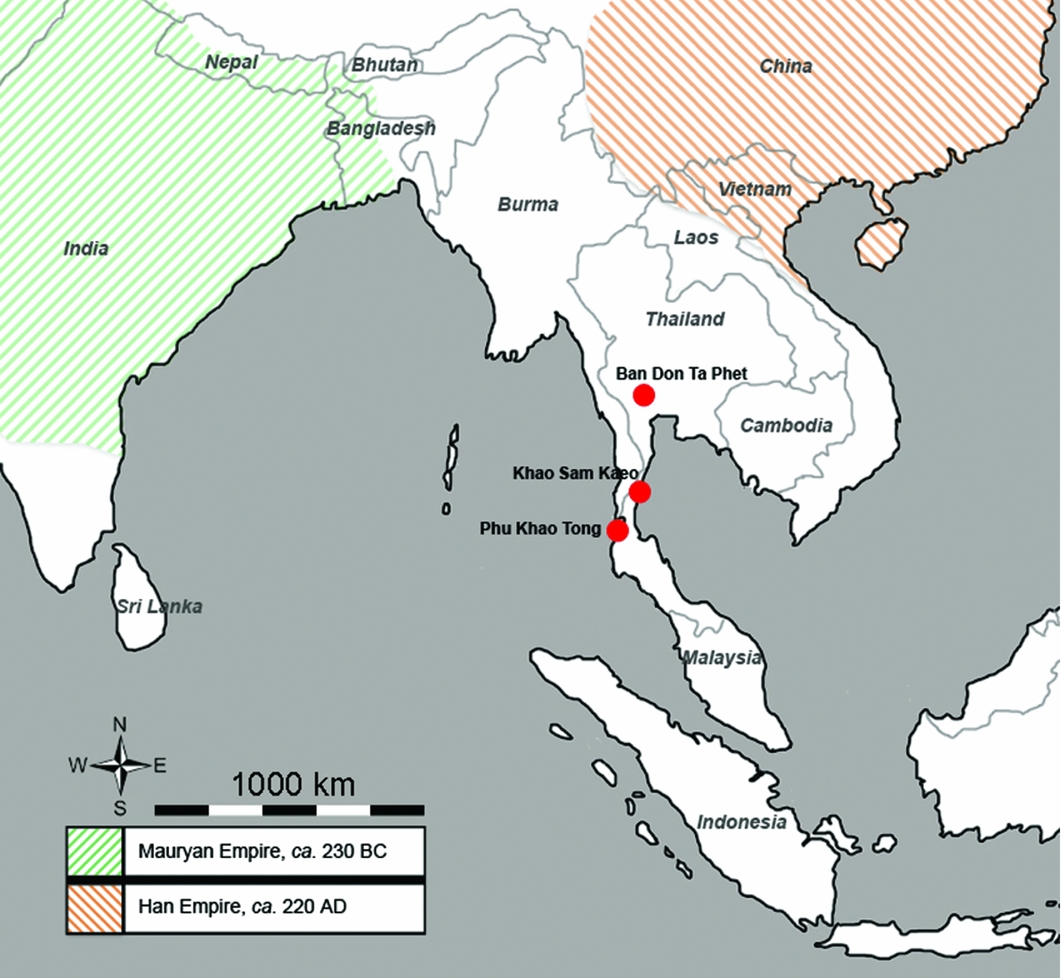

Exchange routes and coastal sites that form part of a trade network have been the subject of much academic scholarship, especially those pertaining to the Indo-Roman trade (Miller Reference Miller1969; Tomber Reference Tomber2008; van der Veen Reference van der Veen2011). People moving along early exchange routes required areas for rest, nourishment, safe harbour, boat repairs and victualling. Regional entrepôts (trading centres) in the ancient world were central to the consolidation and redistribution of goods (Miller Reference Miller1969; Tomber Reference Tomber2008). Entrepôts were also important for cultural exchange, bringing people of diverse backgrounds together and providing a context for the transfer of knowledge and materials, such as approaches to cooking and ingredients. This paper investigates such exchanges through the archaeobotany of two entrepôt sites in the Thai-Malay Peninsula: Phu Khao Thong and the early urban centre of Khao Sam Kaeo (hereafter PKT and KSK respectively, Figure 1). Both sites date to the later part of the first millennium BC, a period when the Thai-Malay peninsula connected the maritime silk roads linking the Mauryan and Han Empires from the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea; as early as the second century BC, the Thai-Malay Peninsula appears in a Chinese Han text (Ch'ien Han Shu) as an overland route to the Indian Ocean and India (Jacq-Hergoualc'h Reference Jacq-Hergoualc'h2002).

Figure 1. Map showing the archaeological sites mentioned in the text, and the extent of the Han and Mauryan Empires c. third century BC.

The archaeobotanical study of KSK contributes to our understanding of how an early port of trade identified in the South China Sea, with an active exchange network and specialised craft production, would have supported itself. We found evidence for exchanged foodstuffs and information on the agricultural base that sustained the different communities at KSK, which included the local population, temporary settlers and transient voyagers (Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014; Bellina in press). The archaeobotany at PKT provides comparative evidence from a contemporaneous site on the Thai-Malay Peninsula, which might have had more direct links with India. PKT and KSK are both strategically located close to the coast, and would have formed a link between the west and east coasts of the peninsula.

Description of the sites, material culture and chronology

The Metal Age site of Khao Sam Kaeo is located in Chumphon province, 8km from the coast (10°31′–32′ N; 99°11′–12′ E; Figure 2). The site consists of four hills, with a peak elevation averaging 30m asl. It is surrounded by lowlands and flanked to the west by the Tha Tapao River. Although an early port city, KSK was not a coastal site, but had access to the sea via the Tha Tapao. Settlements have been found on the plateaus, the slopes of the four hills and on the riverbank. Both domestic and industrial areas have been identified, as well as communal habitation terraces. Several types of structure can be found at the site including terraces, floors, postholes, walls and drainage systems. The site's boundaries are defined by the excavations undertaken across 135 (2 × 2m) units, and extend to approximately 34ha in area.

Figure 2. Google Earth images situating the sites KSK and PKT in the surrounding landscape.

The main settlement period at KSK dates from the fourth to first centuries BC, based on 34 radiocarbon dates (20 of which are AMS) (Table S1 in online supplementary material) and artefact typology. KSK has been identified as the earliest urban settlement in Southeast Asia that was engaged in trans-Asiatic exchange networks (Bellina-Pryce & Silapanth Reference Bellina-Pryce and Silapanth2008; Bellina Reference Bellina2014, in press; Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014). Several communities are represented, and the presence at KSK of craft specialisation in the form of glass working, stone ornament production, metalworking and pottery has been established (Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014). While some items originated from Indian, Chinese and Southeast Asian locations, others were produced at KSK using transferred technologies. KSK provides data on the beginnings of a long-lasting cultural exchange that linked South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The links between South Asia and East Asia at KSK are well documented. Some artefacts from KSK compare with similar items in South Asia and China (Figure 3), such as rouletted ware, seals inscribed with Brahmi script and carnelian artefacts in the form of auspicious symbols from India, and stamped/impressed ceramics and mirrors from Han China. KSK also forms part of a network with other Southeast Asian sites, as seen by artefacts such as Dong Son drums, semi-precious beads, iron-socketed billhooks, glass beads, glass bracelets and raw material such as nephrite blocks (Lankton et al. Reference Lankton, Dussubieux and Gratuze2006; Pryce et al. Reference Pryce, Bellina and Bennett2006; Calo Reference Calò2009; Glover & Bellina Reference Glover, Bellina, Manguin, Mani and Wade2011; Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014; Bellina in press).

Figure 3. Artefacts from KSK: A) Han sherds; B) Han mirror; C) carnelian artefacts in the form of auspicious symbols; D) Dong Son drum; E) iron-socketed billhook; F) bicephalous earring; G) seals with Indian Brahmi script.

Phu Khao Thong (PKT) is a small hill also located in the Kra Isthmus but on the western coast of the peninsula (9°22′49″ N; 98°25′19″ E; Figure 2). It is located 2.8km from the Andaman Coast and 152km from KSK, as the crow flies. In Thai, the name ‘Phu Khao Thong’ translates to ‘gold hill’, referring to the many gold artefacts that were found there. PKT was the first point of entry for ships from South Asia, and, as with KSK, it was an entrepôt, albeit smaller. So while there is some evidence of postholes at PKT, signifying that there was indeed an occupation, it was not an urban settlement, but rather part of a trading complex situated in a bay and protected from the open sea by small islands (Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014).

PKT's chronology overlaps with that of KSK, although it remained active throughout the early centuries AD. The chronology at PKT is based on four AMS radiocarbon dates, from 200 BC–AD 20 (Table S2), as well as the largest corpus of Indian rouletted ware so far known in Southeast Asia (300–1 BC). Pottery inscribed with Tamil-Brahmi script has been dated to the second century AD, and another in Brahmi script is from the fourth century AD (Chaisuwan Reference Chaisuwan, Manguin, Mani and Wade2011).

The resource base

Plant remains at both sites were recovered using the bucket wash-over flotation method with 250µm mesh bags. The samples were sorted and identified at the UCL's Institute of Archaeology down to 0.5mm using a low-powered microscope. The analysed plant macroremains came from contexts pertaining to habitation structures, platforms, craft production areas and middens from nearby occupation areas (Castillo Reference Castillo2013). The plant macroremains identified so far have yielded five domesticated crops at KSK and seven at PKT (Table 1; Figure 4). The three cereals identified were domesticated in three distinct centres of origin: rice (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica) in the Yangtze Basin in China, foxtail millet (Setaria italica) in northern China and finger millet (Eleusine cf. coracana) from East Africa. Numerous pulses were found, mostly of Indian origin (Vigna radiata, Vigna mungo, Macrotyloma uniflorum). The rice bean (Vigna cf. umbellata) of Southeast Asian origin was identified at KSK and PKT for the first time in an archaeological context. Another Southeast Asian domesticate, the pomelo (Citrus cf. maxima) was also identified for the first time, at both sites, providing evidence for arboriculture. Some evidence of ‘cash’ crops or traded plant products included cotton (Gossypium cf. arboreum) and sesame (Sesamum indicum), neither of which are native to southern Thailand.

Table 1. Seed crops identified at Khao Sam Kaeo and Phu Khao Thong, the regions of their origin, and dates of domestication and references on origins of species.

Figure 4. Archaeological cereals and pulses: A) rice caryopses from PKT; B) foxtail millet grain from KSK; C) finger millet from PKT; D) mung bean from PKT; E) black gram from PKT; F) horsegram from PKT; G) hyacinth bean from KSK; H) grass pea from PKT; I) pigeon pea from KSK.

At both sites, a large component of the dataset came from wild/weed species. Often weed flora is used by archaeobotanists to define systems of land use and cultivation practices (e.g. Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Palmera, Jones, Charles and Hodgson1999; Fuller & Qin Reference Fuller and Qin2009). To investigate the type of cultivation systems in place, modern agricultural fields have been examined for weeds that occur with crops. Based on modern evidence for rice weed ecology (e.g. Soerjani et al. Reference Soerjani, Kostermans and Tjitrosoepomo1987; Galinato et al. Reference Galinato, Moody and Piggin1999; Weisskopf et al. Reference Weisskopf, Harvey, Kingwell-Banham, Fuller, Kajale and Mohanty2014), the weeds at KSK and PKT indicate rain-fed or dry rice systems.

Subsistence regime and farming

At KSK and PKT, the ubiquity of a few taxa indicates low diversity and a focus on the cultivation or consumption of only a small number of species. Rice was the main cereal at both sites, and was probably cultivated in nearby hinterlands. In addition to being the most important cereal there today, it also forms a significant part of the overall assemblage in KSK and PKT, occurring in 51% and 82% of samples respectively. Based on morphometric and genetic analyses, the rice found at both sites was identified as the Chinese domesticate O. sativa ssp. japonica (Castillo et al. Reference Castillo, Tanaka, Sato, Kajale, Bellina, Higham, Chang and Fuller2015). While the Indian populations at PKT and KSK could have brought the Indian variety of rice, O. sativa ssp. indica, there was no imperative to do so because rice was already available in Southeast Asia (Castillo Reference Castillo2011). Instead, these immigrant groups might have brought other species not locally available, such as the pulses discussed below.

Rice is represented by several plant parts, including grains, spikelet bases and lemma apiculi (the tip of the rice husk). Spikelet bases can be divided into wild, domesticated and immature forms. At these sites, more than 85% have the irregular and torn-out scar found in domesticated-type rice (Figure 5A; n = 1215 at KSK, and n = 637 at PKT).

Figure 5. Rice plant parts from KSK: A) domesticated rice spikelet base; B) wild rice spikelet base; C) lemma apiculi.

Lemma apiculi displaying an angled or squared fracture indicate the presence of awned rice. Several lemma apiculi with a squared fracture where the awn would have been attached were found at both sites (Figure 5C). Wild rice always has awns, but although awnlessness is a trait of domesticated rice, there are some domesticated rices with awns, especially amongst tropical japonica or javanica rices, such as modern Indonesian bulu. Using domesticated spikelet bases and grain metrics, we infer the presence of an awned variety of tropical japonica. Such forms are typical of dryland and rain-fed systems of cultivation in Southeast Asia (Fuller & Castillo Reference Fuller, Castillo, Lee-Thorp and Katzenberg2016), and, as already noted, the weed assemblage is dominated by dryland rice weeds. Furthermore, other cultivars found at both sites, such as mung bean (Vigna radiata), are normally grown in dryland cultivation systems. A dry, rain-fed cultivation regime is further confirmed by the geomorphological analysis conducted in KSK by Allen (Reference Allen and Bellina2009), who suggests that cultivation probably took place on the gently sloping plateau land and hill slopes. Dryland rice cultivation is characterised by a water source derived from rainfall, and by fields without embankments to retain standing water. Modern fields in Southeast Asia demonstrate a suite of weed flora associated with rice cultivation, and have been compared to the weed flora associated with rice at KSK and PKT (Castillo Reference Castillo2013).

While the rice recorded at KSK and PKT was of the japonica subspecies that originated in China, dryland cultivation in Metal Age Thailand was different from the rice cultivation systems found in China during the same period, which were wetland systems, i.e. in fields that could retain standing water (Fuller & Qin Reference Fuller and Qin2009; Weisskopf et al. Reference Weisskopf, Qin, Ding, Ding, Sun and Fuller2015). From the examination of the archaeobotany of the two Thai sites, it seems probable that wetland rice agriculture was not introduced to the Thai-Malay Peninsula during the last centuries BC. Moreover, the early period of Indian contact did not lead to the translocation of Indian rices (indica) to Southeast Asia. Indica rice is the dominant species cultivated in modern Thailand, and wetland rice agriculture is practised throughout the region today. Therefore, it is posited that labour-intensive wetland rice agriculture (of indica rice) was introduced after sustained Indian contact in the middle of the first millennium AD, and associated with the development of Indic states in mainland Southeast Asia (Castillo & Fuller Reference Castillo, Fuller, Bellina-Pryce, Pryce, Bacus and Wisseman-Christie2010).

Contacts with India

The material artefacts link India with KSK, either through trade or settled Indian communities of traders, craftspeople and religious men (Bellina et al. Reference Bellina, Silapanth, Chaisuwan, Allen, Bernard, Borell, Bouvet, Castillo, Dussubieux, Malakie, Perronnet, Pryce, Revire and Murphy2014). Indian artefacts (i.e. worked stone and glass beads), imports (Indian Fine Paste Ware, raw materials for industries) and foodstuffs may indicate an enclave at KSK. Furthermore, the examination of the pulses and cash crops found at both KSK and PKT contributes to our understanding of trade networks and exchanges with India.

In general, the movements of crops show that people bring with them their preferred, familiar species. In Peninsular Thailand, the Indian community brought a suite of pulses that were formerly unknown in the area, or at least, if present in the wild, undomesticated, such as the mung bean. Mung bean (Vigna radiata), horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum) and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) were found in both KSK and PKT; but PKT, located on the India-facing coast, had a larger suite of pulses of Indian origin. This included black gram (Vigna mungo) and grass pea (Lathyrus sativus), which were not found at KSK. Grass pea is originally from either the Near East or the Balkans, and came to India before 2000 BC. The grass pea, together with other finds in the Thai-Malay Peninsula such as hyacinth bean (cf. Lablab purpureus) and finger millet (Eleusine coracana), provides evidence of early translocations from as far afield as East Africa and, in the case of the latter two, via India by at least 1600 BC and 1000 BC respectively (Fuller & Boivin Reference Fuller, Boivin and Lefevre2009).

While the cultivars found at KSK and PKT demonstrate links with foreign groups, not all new food crops became incorporated in the traditions of Southeast Asian agriculture. The adoption (or lack thereof) of certain foreign crops, may have been affected by social and cultural meanings ascribed to food or culinary versatility. For example, horsegram, domesticated in India in the third millennium BC, was not adopted by the local populations in the Thai-Malay Peninsula in prehistory even though other similar crops were, probably because of culinary versatility and a perception of it as a low-status food. Today, horsegram is considered a poor person's pulse in India (van Wyk Reference van Wyk2005), and it does not make good bean sprouts, an important and preferred Southeast Asian way of eating beans nowadays. By contrast, the mung bean plant is very versatile. The seeds can be dried and stored for use at a later date, or they can be germinated and eaten as bean sprouts. The whole plant can also be used as fodder. In South Asia, split mung beans are cooked with spices and made into dhal. In Southeast Asia, they are also used in confectionery, or made into fine noodles (vermicelli). The mung bean is the most important pulse grown in Thailand today, and was introduced to the Thai-Malay Peninsula by at least the second century BC before becoming embedded in regional agricultural traditions. By contrast, horsegram did not take root in Southeast Asia, and was reintroduced experimentally during British colonialism (Burkill Reference Burkill1935).

As with horsegram, grass pea, found only at PKT, does not seem to have been widely adopted after its initial introduction to the Thai-Malay Peninsula, as it does not form part of the modern Thai diet. This is probably because the grass pea is another poverty food, currently important in areas where food shortages frequently occur, such as central India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal and Ethiopia (Mahler-Slasky & Kislev Reference Mahler-Slasky and Kislev2010). Grass pea contains a neurotoxic amino acid, which is hard to remove. When grass pea is consumed in great quantities, this toxin causes lathyrism, an irreversible crippling disease (Muehlbauer & Tullu Reference Muehlbauer and Tullu1997). Despite these significant disadvantages, it is still eaten routinely by the poor or during famine in India and Ethiopia because it grows well under harsh conditions and in poor soils, although it failed to persist in Southeast Asian traditions.

Other pulses cultivated in present-day Thailand, following their initial introduction from South Asia, include the pigeon pea and the hyacinth bean. Pigeon pea is an important crop grown by the hill tribes in Thailand (Anderson Reference Anderson1993). It thrives on fertile soils and in both humid and drier areas, and it is intercropped with millets, cotton or groundnut. In Laos, upland farmers from many ethnic groups cultivate both pigeon pea and mung bean alongside rice (Roder et al. Reference Roder, Keoboulapha, Vannalath and Phouaravanh1996). So far, the KSK and PKT Cajanus and cf. Cajanus seeds are the earliest found in Southeast Asia, and this crop persisted in regional agriculture. Today, the preference is for fresh pigeon pea seeds and pods eaten as vegetables, although roasted seeds are also eaten (van der Maesen Reference Van der Maesen, van der Maesen and Somaatmadja1989). Likewise, the immature pods of the hyacinth bean are a popular vegetable in Southeast Asia. Other parts of hyacinth bean are also eaten as vegetables—the leaves, young shoots and inflorescences (Shivashankar & Kulkarni Reference Shivashankar, Kulkarni, Van der Maesen and Somaatmadja1989).

Early trade relations

Trade is best demonstrated at both sites by commodity crops, raw materials and spices, including cotton and sesame (Figure 6). The earliest evidence for cotton in the Old World dates to c. 4500 BC from Mehrgarh in Pakistan (Moulherat et al. Reference Moulherat, Tengberg, Haquet and Mille2002), and it then spread through much of India by 1000 BC (Fuller 2008). Although this cannot be verified from charred archaeological remains, this is believed to be South Asian native tree cotton (Gossypium arboreum). The finds from KSK are also probably of this species, although they may have been imported as unprocessed raw material rather than cultivated locally. Earlier evidence of cotton in Southeast Asia comes from the central Thai site Ban Don Ta Phet dating to the fourth century BC, a site that also shows links to India and China in its material culture (Cameron Reference Cameron, Bellina-Pryce, Pryce, Bacus and Wisseman-Christie2010; Glover & Bellina Reference Glover, Bellina, Manguin, Mani and Wade2011). Thailand, especially in the very wet south, is not a favourable area for growing cotton because of the unpredictability of rainfall and the lack of cold weather, which would otherwise reduce the impact of pests (Nuttonson Reference Nuttonson1963). In the early part of the twentieth century, Europeans made several failed attempts to introduce various cotton species to Southeast Asia including the Malay Peninsula (Burkill Reference Burkill1935). It follows that the farmers at KSK or Ban Don Ta Phet may have encountered the same problems. While a thread of cotton found at Ban Don Ta Phet could represent traded textile, the funicular cap (a seed part) recovered from KSK suggests on-site processing of the bolls into fibre, pointing to the importation of raw, unprocessed cotton, probably from India.

Figure 6. Plant species from KSK and PKT: A) cotton funicular cap from KSK; B) sesame from PKT; C) cotyledons of rice bean from PKT; D) Citrus sp. rind fragment from KSK.

Sesame was domesticated in South Asia. While it may have reached Mesopotamia as early as the third millennium BC (Bedigian Reference Bedigian2004; van der Veen Reference van der Veen2011), the earliest evidence for cultivation comes from the Harappan civilisation areas in Pakistan and adjacent India (Bedigian Reference Bedigian2004; Pokharia et al. Reference Pokharia, Kharakwal, Rawat, Osada, Nautiyal and Srivastava2011). A single sesame seed at PKT is, so far, the earliest evidence of sesame appearing to the east of India; it is important as it signals the beginnings of circulation eastwards, prior to its introduction into Han China more than 2000 years ago. A Chinese textual reference (Bencao Gangmu—Standard Inventory of Pharmacology) compiled in the sixteenth century AD mentions the introduction of sesame to China during the Western Han Dynasty (Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Zhang, Bedigian, Li, Wang and Jiang2012).

Local crops

The only foodstuffs found at KSK and PKT that represent indigenous domesticates from Thailand are rice bean and citrus fruit rind, probably from pomelo (Citrus maxima) (Figure 6). Charred rind fragments have been identified as either cf. Citrus or Citrus sp. following favourable comparison with pomelo anatomy (rather than mandarin oranges or citrons). The definite origins of pomelo are still unknown, but Thailand and mainland Southeast Asia are generally posited (Weisskopf & Fuller Reference Weisskopf, Fuller and Smith2013). The most productive pomelo orchards in modern Thailand are found on riverbanks or former riverbanks (Niyomdham Reference Niyomdham, Coronel and Verheij1991). KSK and PKT fit all the criteria for optimal growing conditions of pomelo, and there is today a commercial pomelo orchard located in valley 2 at KSK. There is evidence from charcoal and historical linguistics for citrons, and probably for some form of orange in southern India at this period, but there is no evidence for an early transmission from Thailand to India of the pomelo (Fuller Reference Fuller, Petraglia and Allchin2007).

Rice bean is a traditional crop in Southeast and East Asia (Isemura et al. Reference Isemura, Tomooka, Kaga and Vaughan2011). Genomic studies suggest domestication in northern Thailand, where the wild progenitor Vigna umbellata var. gracilis is found and the greatest genetic diversity occurs (Isemura et al. Reference Isemura, Tomooka, Kaga and Vaughan2011). Although rice bean is consumed in modern-day India by tribes in the eastern and north-eastern mountainous areas (Arora et al. Reference Arora, Chandel, Joshi and Pant1980), it is more important in Burma and farther east. The KSK and PKT finds suggest that rice bean had already been domesticated in northern Thailand prior to the third century BC. Rice bean may have been introduced from northern Thailand, via a northern route (such as through Burma and Bangladesh) to north India. Likewise, rice bean was probably brought from the north of Thailand and cultivated in Peninsular Thailand.

Conclusions

KSK and PKT became areas of cross-cultural interaction for ideas, technologies and goods due to the influence of, and contact with, South Asia, East Asia and Insular Southeast Asia. The evidence for the trade of ornaments, pottery and metal objects is complemented by that of perishables such as food grains and cotton, which also formed part of the exchange network, and eventually became incorporated into the agricultural diversity of Southeast Asia. From the perspective of food and agriculture, there were strong connections with India, including the probable import of cotton, and perhaps sesame, as well as the introduction of pulses, although apparently not rice of the indica subspecies. All of these pulses might have been grown locally, but only mung bean, pigeon pea and hyacinth bean became part of the long-term agricultural production in Thailand. Also, only certain crops were exported or deemed worthy of adoption abroad, with neither rice bean nor pomelo evidenced in early Indian archaeology despite their cultivation and availability in Thailand during this period. Entrepôts, such as KSK and PKT, brought together different cultural groups with varied dietary traditions and plant products, including cultivable seeds from many regions. In this context, crops may be thought of as having been auditioned for inclusion in the local culinary palette and agro-ecological system, with only a subset passing the test and entering into Southeast Asian agricultural traditions.

Acknowledgements

Research by Castillo and Fuller on the rice and rice weeds of these sites is supported by a grant from NERC (UK) on ‘The impact of evolving of rice systems from China to Southeast Asia’ [NE/K003402/1]. PhD research by Castillo was supported by the AHRC. Excavations of KSK and PKT were directed by Bellina and supported by the CNRS and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We would also like to thank Katsunori Tanaka (Hirosaki University) for the aDNA work done on rice from KSK and PKT.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.175