Introduction

Given the popularity of faultlines and their ability to explain more complex team dynamics than team diversity (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson, Reference Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp and Gilson2008), scholars have explored the effects of faultlines (e.g., Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto, & Thatcher, Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). The influences of dormant faultlines on team outcomes remain unclear despite the vast amount of faultline research that has been conducted. While a meta-analytic study found a general ‘bad’ effect of faultlines on team outcomes (Thatcher & Patel, Reference Thatcher and Patel2012), some studies reported ‘good’ effects of faultlines (Li, Zhang, & Wei, Reference Li, Zhang and Wei2018; Ma, Xiao, Guo, Tang, & Singh, Reference Ma, Xiao, Guo, Tang and Singh2022). The faultline literature is rife with conflicting findings and provides managers and researchers with ambiguous guidance. We believe that the oversimplification of team faultlines is one of the leading causes of the inconsistency. We argue that making a general conclusion about the impact of different faultlines is a flawed strategy and that the study should be directed by a more nuanced understanding of the faultline itself. We need to clarify how different faultlines affect team outcomes in different ways. The answers to this question are crucial since they could expand our knowledge on how to manage diverse teams according to faultline types.

Thatcher and Patel (Reference Thatcher and Patel2012) have provided a promising typology of faultlines. They argued that faultlines may evolve as time goes on because team members initially judge each others’ differences based on surface-level attributes but become aware of deep-level attributes in the long term. In light of this, in Study 1, we distinguish between surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines in our meta-analysis and develop a contingency framework to test the temporally contingent effects of surface-level and deep-level faultlines on subgroup formation, team interaction quality, and team performance. Furthermore, researchers have argued that social faultlines are expected to be harmful, whereas task faultlines are expected to be beneficial to teams (e.g., Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). Therefore, in Study 2, we subdivided surface-level and deep-level faultlines into four categories (e.g., surface-level social faultlines, surface-level task faultlines, deep-level social faultlines, and deep-level task faultlines) and examined how four types of faultlines will impact social and task interaction quality. Meta-analysis is particularly suited to deal with these questions as it can include a large amount of the faultline literature that allows testing and comparing the effects of various faultlines.

Another debate in the faultline literature is whether dormant faultlines can directly influence team outcomes without being activated into subgroups. Jehn and Bezrukova (Reference Jehn and Bezrukova2010) suggested that dormant faultlines do not necessarily shape team interactions and performance; instead, dormant faultlines will be transformed into actual separate subgroups and shape the team interaction processes only when they are activated. However, empirical studies have found that dormant faultlines can impact team outcomes even when they are not activated into subgroups (e.g., Chrobot-Mason, Ruderman, Weber, & Ernst, Reference Chrobot-Mason, Ruderman, Weber and Ernst2009). Thatcher and Patel's (Reference Thatcher and Patel2012) meta-analytical review has compared the effects of dormant faultlines and activated faultlines (i.e., perceived subgroup formation) and found that the effects of activated faultlines (i.e., perceived subgroup formation) are stronger than dormant faultlines. But their meta-analysis did not further test the linkage between dormant faultlines and perceived subgroup formation. Accordingly, this meta-analysis aims at addressing this gap by developing a serial mediation framework and exploring how the initial dormant faultlines trigger the subgroup formation and then influence team interaction quality and team performance.

We seek to solve the above debates and extend the faultline literature in several ways. First, our meta-analysis contributes to the faultline literature by distinguishing between different types of faultlines. Study 1 found that surface-level and deep-level faultlines exert differentiated effects over time. In Study 2, we further tested the differentiated effects of social and task forms of surface-level and deep-level faultlines on team interaction quality. The distinguishing of faultline types extended our knowledge of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ sides of faultlines, thus contributing to solving the first debate.

Second, by proposing and testing a framework to bridge dormant faultlines and perceived subgroup formation, this meta-analysis provides a deeper understanding of team interaction caused by faultlines. Study 1 found that both surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines rely on the perceived subgroup formation and interaction quality to exert a negative influence on team performance. Study 2 further clarified that only the harmful effects of dormant faultlines (i.e., surface-level social faultlines, deep-level social, and task faultlines) work through subgroup formation. In contrast, the beneficial effects of surface-level task faultlines do not rely on the perception of subgroup formation. These findings solve the second debate.

Theoretical Background

Comparison Between Dormant Faultlines and Subgroup Formation

It is important to note that in this research, we do not assume that dormant faultlines necessarily produce corresponding subgroups. We illustrate the difference between dormant faultlines and perceived subgroups. (1) Dormant faultlines are defined as ‘hypothetical dividing lines that may (or may not) split a group into subgroups’ (Lau & Murnighan, Reference Lau and Murnighan1998: 328). Thus, the existence of dormant faultlines implicates compositional splits in teams. (2) Subgroups form when team members perceive faultlines as the actual division into several subgroups (Jehn & Bezrukova, Reference Jehn and Bezrukova2010). And these subgroups are ‘internally homogeneous and externally heterogeneous’ (Yu, Deng, Gao, & Liu, Reference Yu, Deng, Gao and Liu2022: 13). Thus, there is a conceptual distinction between dormant faultlines and subgroup formation.

Taxonomy of Dormant Faultlines

To understand the differentiated influences of faultlines, we classified faultlines into surface-level and deep-level faultlines, which are theoretically driven and consistent with previous diversity taxonomies (Harrison, Price, & Bell, Reference Harrison, Price and Bell1998). It is critical to measure the effect sizes of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines and compare their temporally contingent effects.

Surface-level faultlines

Surface-level faultlines are ‘hypothetical dividing lines’ among team members based on readily detectable characteristics (Ren, Gray, & Harrison, Reference Ren, Gray and Harrison2015). Such characteristics include age, sex, race/ethnicity, education and functional background, and tenure (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price and Bell1998). This meta-analysis categorizes faultlines formed around these characteristics into surface-level faultlines. Further, we distinguish between surface-level social and task faultlines. Surface-level social faultlines are surface-level faultlines based on members’ alignment on social category demographics, such as gender, age, race, and nationality (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). In contrast, surface-level task faultlines are surface-level faultlines based on characteristics that are directly related to work tasks, such as work experiences and educational backgrounds (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009) (see Table 1).

Table 1. The labels of variables

Deep-level faultlines

Deep-level faultlines are defined as ‘hypothetical dividing lines’ among team members forming from underlying personality traits, beliefs, and norms (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Gray and Harrison2015). Such characteristics include personality, values, attitudes, and decision-making styles that are only learned through extended interaction and information exchange because they unfold as interaction time increases (Harrison, Gavin, & Florey, Reference Harrison, Gavin and Florey2002). We categorize faultlines formed around these characteristics into deep-level faultlines. We realize that surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines are distinct theoretical constructs and may have different effects over time. In addition, we distinguish between deep-level social and task faultlines. Deep-level social faultlines are based on members’ alignment on social psychology characteristics, such as relationship values, personalities, attitudes, and cultural orientations. In contrast, deep-level task faultlines are based on unobservable cognitive features related to team tasks, such as decision-making style faultlines, goal commitment, and task meaningfulness (see Table 1).

The Present Research

Two meta-analyses were designed to examine the differentiated impacts of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines. Study 1 examines the indirect effects of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines on team performance through subgroup formation and team interaction quality and tests how the effects of surface-level and deep-level faultlines differentiate over time.

Study 2 mainly focuses on faultlines’ effects on team interaction quality. Meta-analysis is conducted, and it aims to further examine how surface-level social faultlines, surface-level task faultlines, deep-level social faultlines, and deep-level task faultlines will impact social and task interaction quality, respectively.

Study 1

Hypotheses

Dormant faultlines and subgroup formation

Subgroups are likely characterized by team composition, such as dormant faultlines (Lau & Murnighan, Reference Lau and Murnighan1998). The dormant faultlines are important predictors of subgroup formation. When strong surface-level faultlines exist, there are salient boundaries between team members with dissimilar attributes. According to social categorization theory (SCT, Turner, Sachdev, & Hogg, Reference Turner, Sachdev and Hogg1983), team members are likely to be categorized into similar ‘in-group’ and dissimilar ‘out-groups’ on the basis of salient surface-level characteristics (Cooper, Patel, & Thatcher, Reference Cooper, Patel and Thatcher2014). People tend to come in contact more with similar (in-group) members than that with dissimilar (out-group) others (Brewer & Brown, Reference Brewer, Brown, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzay1998). In this case, network ties tend to be built among members with similar surface-level characteristics (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001). Thus, similar team members are aggregated into dense subgroups, and there are more mutual interactions among members in a homogeneous subgroup than those between different subgroups, increasing the likelihood of subgroup formation.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): There will be a positive relationship between surface-level faultlines and subgroup formation.

The attraction-selection-attrition model (Schneider, Goldstiein, & Smith, Reference Schneider, Goldstiein and Smith1995) has been used to explain how deep-level faultlines based on unobservable characteristics will trigger subgroup formation. They suggest that people prefer interacting with those who are similar in psychological traits (e.g., values, attitudes, beliefs, and personality) or cognitive features (e.g., decision-making style, task goal commitment, and task meaningfulness). The reason is that these features verify and reinforce their own expressed behaviors (e.g., Swann, Stein-Seroussi, & Giesler, Reference Swann, Stein-Seroussi and Giesler1992). Accordingly, when strong deep-level faultlines separate team members into different categories, team members will be attracted to develop interpersonal interactions with members who have similar psychological characteristics or cognitive features, rather than those in other categories. Therefore, team members tend to categorize themselves into subgroups according to deep-level faultlines.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): There will be a positive relationship between deep-level faultlines and subgroup formation.

Further, we proposed that deep-level faultlines were expected to be more influential than surface-level faultlines in forming subgroups. First, more accurate and straightforward implications about others can be inferred from deep-level characteristics (Larson, Reference Larson2007). For instance, understanding deep-level characteristics have been found to be more influential in attraction, make interpersonal interaction more rewarding, and reduce role ambiguity (Van Emmerik & Brenninkmeijer, Reference Van Emmerik and Brenninkmeijer2009). Previous studies also confirmed that deep-level characteristics have more influential effects on team interaction than surface-level characteristics (Larson, Reference Larson2007). Second, Phillips, Northcraft, and Neale (Reference Phillips, Northcraft and Neale2006) suggested that learning deep-level characteristics would erode the legitimation of surface-level differences. Hence, we argue that faultlines based on deep-level characteristics are more influential in shaping team members’ interactions and appear to have more salient and consistent effects on the formation of subgroups than surface-level faultlines.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c): Deep-level faultlines have stronger effects on subgroup formation than surface-level faultlines.

Subgroup formation and team interaction quality

When team members are polarized into opposing subgroups, they tend to dehumanize members of other subgroups and value members in their own subgroups. For example, people from different subgroups are likely to have negative effects on each other (Hornsey & Hogg, Reference Hornsey and Hogg2000). In addition, team members in different subgroups will find it challenging to understand each other and accept one another's ideas (Jiang, Jackson, Shaw, & Chung, Reference Jiang, Jackson, Shaw and Chung2012). Therefore, the formation of subgroups is likely to decrease the team interaction quality, such as triggering conflict, detracting from mutual trust and respect, and hindering team learning, information elaboration, and integration (Cronin, Bezrukova, Weingart, & Tinsley, Reference Cronin, Bezrukova, Weingart and Tinsley2011). Conceptualizing team interaction quality as the perception of the status of the relational and informational interaction processes among team members (Kirk, Hekman, Chan, & Foo, Reference Kirk, Hekman, Chan and Foo2022), it follows that the subgroup formation should undermine the team interaction quality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): There will be negative relationships between subgroup formation and team interaction quality.

Team interaction quality and team performance

We argue that team interaction quality will promote team performance. High quality of team interaction indicates beneficial interaction among team members. For example, when team members develop integrated and coherent interaction with each other, they may feel a sense of psychological safety and focus on reaching the team goals (Li & Hambrick, Reference Li and Hambrick2005), which will improve group performance (Vora & Markóczy, Reference Vora and Markóczy2012). In addition, when team members benefit from information elaboration, task learning, and knowledge transfer, they will discuss task-oriented issues and generate new ideas to perform better (Vora & Markóczy, Reference Vora and Markóczy2012). Consequently, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Team interaction quality has a positive relationship with team performance.

The mediation role played by subgroup formation and team interaction quality

We have argued that surface-level and deep-level faultlines among team members may contribute to subgroup formation. Next, the formation of subgroups will decrease the interaction quality. As established previously, the interaction quality will, in turn, act on team performance. Drawing on the arguments above, we suggest that dormant faultlines may not contribute to team performance alone. Instead, dormant faultlines’ effects on team performance rely on subgroup formation and team interaction quality. Altogether, our logic suggests the mediated hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Subgroup formation will mediate the negative effects of surface-level faultlines (a) and deep-level faultlines (b) on team interaction quality.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Team interaction quality will mediate the negative effect of subgroup formation on team performance.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Subgroup formation and team interaction quality will mediate the negative effects of surface-level faultlines (a) and deep-level faultlines (b) on team performance in sequence.

How interaction time matters in network formation

In the previous discussion, we emphasized the importance of dormant faultlines in producing subgroup formation, interaction quality, and performance. We postulated that surface-level and deep-level dormant faultlines work in similar ways. However, team networks are dynamic and never staid as time passes (Marsden, Reference Marsden1990). Drawn from the perspective of social categorization theory (SCT, Turner et al., Reference Turner, Sachdev and Hogg1983), faultlines’ impacts are contingent on categorization salience (Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, Reference Van Knippenberg, De Dreu and Homan2004), which is varying over time. Interaction time allows personal emotions and information to be exchanged between members, deepening team members’ understanding of each other and thus increasing the salience of social categorization. Hence, the present study highlights a critical moderating role for interaction time in research, attempting to unpack the ‘black box’ of the contingent effects of surface- and deep-level faultlines.

The social categorization perspective supports the notion that there will be an automatic categorization based on surface-level characteristics because surface-level attributes are initially salient and accessible (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Gavin and Florey2002). However, if members share only similar surface-level attributes, long interaction time would provide them with more opportunities to learn about each other and discover how little they have in common on unobserved deep-level attributes, reducing the salience of surface-level faultlines (Ziebro & Northcraft, Reference Ziebro, Northcraft, Mannix, Goncalo and Neale2009). In this case, team members view surface-level attributes as less meaningful and relevant when developing their real network ties, choosing interaction strategy, and contributing to team performance in the long term. Accordingly, surface-level dormant faultlines should have weaker long-run effects on subgroup formation, team interaction quality, and performance.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): The effects of surface-level faultlines on subgroup formation (a: less positive), team interaction quality (b: less negative), and team performance (c: less negative) will be weakened in the long term.

In contrast, deep-level faultlines form from psychological attributes (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Gavin and Florey2002). The salience of deep-level faultlines would increase over time since team members have more chances to learn about their deep-level traits with long-term collaboration, enhancing the cognitive accessibility of deep-level attributes. Accordingly, deep-level faultlines may become a salient determinant for team interaction and team performance under long-term interaction. Hence, the time effect would exacerbate the influence of deep-level faultlines.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): The effects of deep-level faultlines on subgroup formation (a: more positive), team interaction quality (b: more negative), and team performance (c: more negative) will be strengthened in the long term.

Methods

Sample

Literature search

Several sources were used to locate suitable studies investigating team faultlines and network properties from 2002 to 2022. First, we searched the computerized databases (including the Social Science Citation Index, PsycINFO, ProQuest, Science Direct, and ABI/INFORM) to find published papers and dissertations using the following keyword combinations: team/group, faultlines, subgroup, and performance. In addition, we supplement the database searches with other search strategies, including manual checks of the references of previous team faultline meta-analyses (e.g., Meyer, Glenz, Antino, Rico, & González-Romá, Reference Meyer, Glenz, Antino, Rico and González-Romá2014; Thatcher & Patel, Reference Thatcher and Patel2012), and manual searches of articles in top journals (e.g., Journal of Applied Psychology, Academy of Management Journal, and Journal of Management). Finally, we searched Google Scholar and contacted researchers in the faultline research field to locate possible unpublished studies. After searching the databases, we initially got 3023 articles.

Study inclusion

After screening for titles and abstracts, we excluded articles that were unrelated, not quantitative studies, and not written in English. Next, we reviewed the remaining 632 full-text articles for eligibility and included studies in this meta-analysis following several criteria. First, we included articles that report sample size, research setting, and appropriate statistics [e.g., correlation coefficient, standard deviation (SD), and reliability coefficient] that are used to compute the effect sizes of the relationships between faultlines, subgroup formation, team interaction, and team performance. Although for TMTs, the performance was measured at the firm-level, we retained these TMT samples. The reason is that firm-level performance is typically reflected by the function of the TMT. Thus, we can generate the effect sizes at the team-level. Second, articles had to contain faultlines based on surface-level or deep-level attributes. Third, since this research was interested in identifying interaction time as a moderator influencing faultline outcomes, studies were required to provide information about team status (continuous or temporary). Finally, we checked for sample overlaps between articles written by the same author(s). Based on the inclusion criteria, 63 articles were excluded as they were not quantitative studies, 350 articles were excluded as they were not related to our focused relationships, 75 articles were excluded due to insufficient data, 42 articles were excluded due to duplication, and 7 articles testing faultlines’ effects at the individual- or the organizational-level were excluded (see Figure 1). Finally, 96 studies in 95 articles were included in this meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Flowchart depicting the systematic review process including reasons for exclusion

Coding

All studies were coded by two authors. We developed a formal coding scheme regarding the different variable categorizations. Next, both coders who are familiar with the faultline and network literature independently coded articles. The high inter-rater reliability coefficients (0.85 to 0.97) suggested a reliable coding process.

Measures

Team dormant faultlines

Drawing on past research (e.g., Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price and Bell1998), we classified team dormant faultlines into surface-level and deep-level faultlines. Surface-level faultlines focused on the alignment of observable attributes such as age, gender, race, educational background, functional background, and tenure. We labeled dormant faultlines as deep-level faultlines if the faultlines are based on unobservable attributes. All these kinds of dormant faultlines were measured by objective approaches. The objective approach to measuring faultlines included in this meta-analysis includes Fau index, FLS (Faultline strength)-Index, Subgroup Strength, Factional Faultlines, and ASW (Average silhouette width, Gibson & Vermeulen, Reference Gibson and Vermeulen2003; Li & Hambrick, Reference Li and Hambrick2005; Meyer & Glenz, Reference Meyer and Glenz2013; Shaw, Reference Shaw2004; Thatcher, Jehn, & Zanutto, Reference Thatcher, Jehn and Zanutto2003). These indexes provide the measurement of faultline strength.

Subgroup formation

Subgroups are ‘subsets of team members that are each characterized by a unique form or degree of interdependence’ (Carton & Cummings, Reference Carton and Cummings2012: 732). Wasserman and Faust (Reference Wasserman and Faust1994) described the subgroups as a set of actors that were relatively dense and directly connected through reciprocated relationships. And the formation of subgroups within a team indicates frequent interaction within a subgroup and less interaction between the subgroups. As shown in Table 1, we set subgroup formation as an umbrella term of various comparable variables in faultline research, such as perceived subgroup formation (interaction pattern: members will develop actual constructive interactions within subgroups while they perceive a competitive divide between subgroups), coalition formation (interaction pattern: members’ behaviors within a coalition involve more closed interactions than those with other parts of the group), and perceived/activated faultlines (interaction pattern: when the faultlines are activated, team members are attracted by similar ones and build more cohesive bounds among subgroup members who share the same attributes). These variables are all comparable to the definition of subgroup formation because they indicate a team interaction structure, such that some team members are aggregated into several dense subgroups, and there are more intense mutual relations among members within the subgroup than those between the subgroups. All variables are measured subjectively through ratings by individuals.

Team interaction quality

Team interaction quality refers to the perceptions of the status of the interaction processes among team members (Kirk et al., Reference Kirk, Hekman, Chan and Foo2022). Cooke and Szumal (Reference Cooke and Szumal1994) demonstrated that constructive team interactions are superior in quality, while passive and aggressive interactions are inferior in quality. The constructive interaction quality is characterized by cooperation, trust, integration, and cohesion that fulfill affiliation needs as well as information exchange and team learning that fulfill problem-solving needs.

The construct of team interaction quality thereby subsumes team members’ perceptions of constructive team interactions, such as team integration, identification, cohesion, relational harmony, cooperation reciprocity, and mutual trust experienced by team members as well as the amount of learning, information sharing and elaboration, communication, and coordination within a team. In addition, high team interaction quality also indicates that a team experience less passive (e.g., hiding information) and aggressive interaction (e.g., conflict and contest) (Potter & Balthazard, Reference Potter and Balthazard2002). Therefore, we also included the inverse terms of knowledge hiding, team conflict, and power struggle as variables of team interaction quality. All the variables of team interaction quality are measured subjectively through ratings by team members.

Team performance

We define team performance as the quantity and quality of team outputs (Schneid, Isidor, Li, & Kabst, Reference Schneid, Isidor, Li and Kabst2015). Team performance was measured as team awards/bonuses, final scores/grades, productivity, profitability, and perceived team performance rated by supervisors or team members (see Table 1). Notably, we did not distinguish between objective and subjective team performance because we found no significant difference in relationships between faultlines and either type of team performance.Footnote 1 When team performance was measured in multiple approaches, we included objective measures (Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009).

Interaction time

We coded interaction time according to the expected length of time that a team exists (Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009). We classified interaction time into short-term and long-term. Student teams taking part in courses and temporal project teams existing for less than one year were classified as short-term teams. Teams existing for longer than one year were considered as long-term (The average team tenure > 1 year).

Meta-analytic techniques

First, to test the hypotheses of bivariate relationships (i.e., Hypotheses 1–3), we used Schmidt and Hunter's (Reference Schmidt and Hunter2015) meta-analytic approaches to synthesize correlation coefficients across the studies. We created the weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error ($\bar{\rho }$![]() ).

).

Second, to test the mediation effects of subgroup formation and team interaction quality (i.e., Hypotheses 4–6), we adopted meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM; Cheung, Reference Cheung2015). In contrast to traditional bivariate meta-analysis, MASEM provides ‘unique statistical power advantages’ (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Aguinis, Heavey, Ketchen, Boyd, Su, Lau and Joo2016: 478). We chose the random effects approach rather than the fixed effects model to calculate effect sizes because of its conservation (Geyskens, Krishnan, Steenkamp, & Cunha, Reference Geyskens, Krishnan, Steenkamp and Cunha2009). When testing the mediation hypotheses, we followed methods developed by Cheung (Reference Cheung2022) to calculate the indirect effects of the structural model.

Third, we conducted detailed moderation analyses to explore whether interaction time would contribute to the heterogeneity of effect sizes. Following Drees and Heugens (Reference Drees and Heugens2013), the moderator analysis was conducted independently from MASEM. The moderator effects of interaction time were tested on the correlation coefficients between each pair of variables but not on specific parameters in a structural equation model. It is because we are interested in how the general effects of surface-level and deep-level faultlines on subgroup formation, team interaction quality, and team performance will evolve over time, respectively. We adopted ANOVA to compare the effect sizes of two categories of interaction time (i.e., short-term and long-term) (Lipsey & Wilson, Reference Lipsey and Wilson2001). A significant QB indicates that the interaction time is a significant moderator and explains the heterogeneity between subgroups (Aguinis, Gottfredson, & Wright, Reference Aguinis, Gottfredson and Wright2011).

Results

Study characteristics

As shown in Appendix I, the 95 articles covered a period from 2002 to 2022, including 63 journal articles, 19 dissertations, 12 conference papers, and one research report. The sample size ranged from 11 to 424.

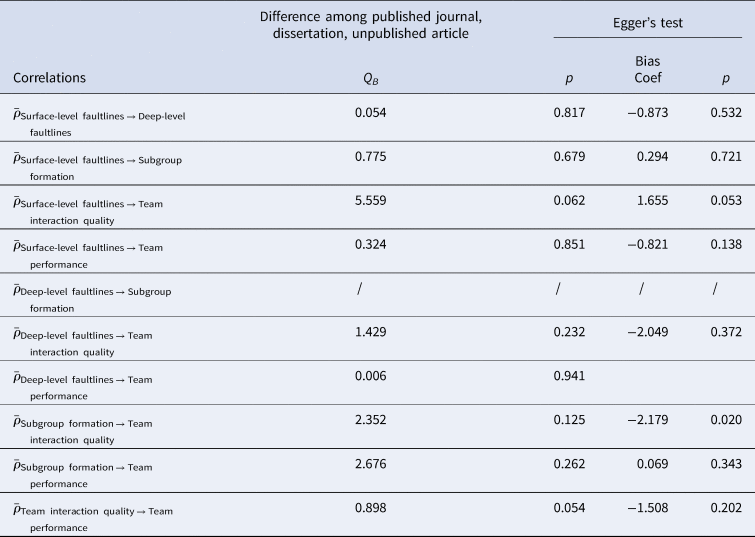

Publication bias

Following Van Dijk, Van Engen, and Van Knippenberg (Reference Van Dijk, Van Engen and Van Knippenberg2012), we tested the between-subgroup differences among the effect sizes of unpublished studies, dissertations, and published papers. The result in Table 2 suggested that there was no publication bias. In addition, we conducted Egger's regression analysis, and the statistics also confirmed no publication bias (see Table 2).

Table 2. Publication bias

Relationships among faultlines, subgroup formations, team interaction quality, and team performance

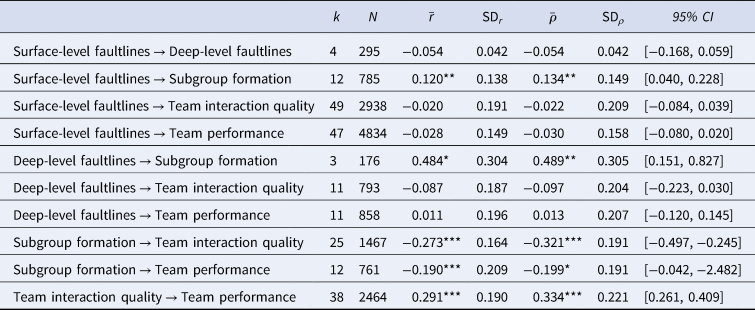

Table 3 summarizes the results of the bivariate correlations between each pair of variables. As shown in Table 3, both surface-level faultlines ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.134; 95% CI [0.040, 0.228]) and deep-level faultlines ($\bar{\rho }$

= 0.134; 95% CI [0.040, 0.228]) and deep-level faultlines ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.489; 95% CI [0.151, 0.827], k = 3)Footnote 2 have significant and positive relationships with subgroup formation, thus supporting Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b. In addition, compared with surface-level faultlines, deep-level faultlines have a more positive effect on network subgroup formation (QB = 14.51, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1c. For Hypothesis 2, we observed a significant and negative relationship between subgroup formation and team interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= 0.489; 95% CI [0.151, 0.827], k = 3)Footnote 2 have significant and positive relationships with subgroup formation, thus supporting Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b. In addition, compared with surface-level faultlines, deep-level faultlines have a more positive effect on network subgroup formation (QB = 14.51, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1c. For Hypothesis 2, we observed a significant and negative relationship between subgroup formation and team interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.321; 95% CI [−0.497, −0.245]). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. For Hypothesis 3, we observed that team interaction quality was significantly and positively related to team performance ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.321; 95% CI [−0.497, −0.245]). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. For Hypothesis 3, we observed that team interaction quality was significantly and positively related to team performance ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.334; 95% CI [0.261, 0.409]). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

= 0.334; 95% CI [0.261, 0.409]). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Table 3. Meta-analytic correlations

Notes: k = total number of effect sizes; N = total sample size; $\bar{r}$![]() = sample-size-weighted mean observed correlations; SDr = standard deviation of observed correlations; $\bar{\rho }$

= sample-size-weighted mean observed correlations; SDr = standard deviation of observed correlations; $\bar{\rho }$![]() = estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; SDρ = standard deviation of $\bar{\rho }$

= estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; SDρ = standard deviation of $\bar{\rho }$![]() ; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around $\bar{\rho }$

; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around $\bar{\rho }$![]() ; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

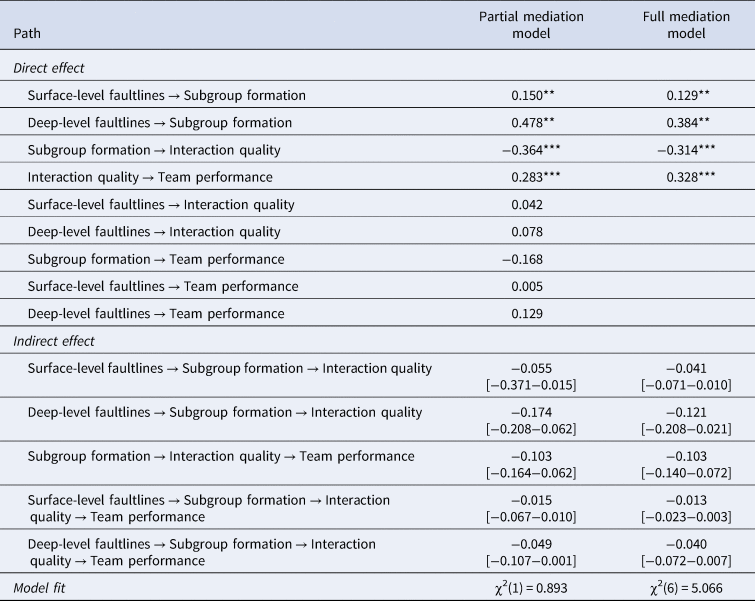

The mediating effects

We conducted MASEM to test the mediation hypotheses (i.e., Hypotheses 4–6). Table 4 provides the meta-analytic correlation matrix. The lower left of the off-diagonal entries provides the weighted mean effect size corrected for measurement error. The upper right of the off-diagonal entries presents the number of studies (k) and the total sample sizes (N) in parentheses.

Table 4. Meta-analytic correlation matrix

Notes: Off-diagonal entries on the lower left contain the reliability corrected and weighted mean effect size. Off-diagonal entries in the upper right present the number of studies k and total sample sizes (N) in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To test the mediation effects, we followed the procedures developed by Cheung (Reference Cheung2022) to calculate the indirect effects. Table 5 shows the results of the direct and indirect effects. First, the result of the partial mediation model in Table 5 illustrates that surface-level faultlines have a significant and negative indirect effect on team interaction quality through subgroup formation (Mediator 1) (Indirect effect = −0.055, 95% CI [−0.371, −0.015]). Meanwhile, the direct effect of surface-level faultlines on team interaction quality becomes insignificant (Direct effect = 0.042, p = 0.253). Therefore, subgroup formation fully mediates the negative relationship between surface-level faultlines and interaction quality, supporting Hypothesis 4a. Similarly, deep-level faultlines also have a significant and negative indirect effect on team interaction quality through subgroup formation (Mediator 1) (Indirect effect = −0.174, 95% CI [−0.208, −0.062]). Meanwhile, the direct effect of deep-level faultlines on team interaction quality becomes insignificant (Direct effect = 0.078, p = 0.510). Therefore, subgroup formation fully mediates the negative relationship between deep-level faultlines and interaction quality, and Hypothesis 4b is also supported. We also found that team interaction quality (Mediator 2) fully mediates the negative relationship between subgroup formation (Mediator 1) and performance (Direct effect = −0.168, p = 0.203, Indirect effect = −0.103, 95% CI [−0.164, −0.062]), which supports Hypothesis 5. Finally, we tested the two serial mediation effects. We found that subgroup formation (Mediator 1) and team interaction quality (Mediator 2) will fully mediate the negative effects of surface-level faultlines (Direct effect = 0.005, p = 0.886, Indirect effect = −0.015, 95% CI [−0.067, −0.010]) and deep-level faultlines (Direct effect = 0.129, p = 0.236, Indirect effect = −0.049, 95% CI [−0.107, −0.001]) on team performance in sequence. Thus, Hypothesis 6a and 6b are supported. Figure 2 presents the standardized path coefficients of the MASEM.

Figure 2. Results of meta-analytical structural equation modeling.

Table 5. Direct and indirect effects and fit Indices of different structural model

Notes: Standardized coefficients are reported; 95% confidence interval around the indirect effects are present in brackets; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Chung, Zhan, Noe, and Jiang (Reference Chung, Zhan, Noe and Jiang2022) suggested comparing alternative structural models using meta-analytic data. The results of the initial model indicate full mediation paths from surface-level and deep-level faultlines on team performance. Thus, we developed a full mediation model as an alternative model. We removed the direct paths from both surface-level and deep-level faultlines to team interaction quality and team performance, and we found that the full mediation model fits better than the initial partial mediation model (χ 2 [6] = 5.066, Δχ 2 [5] = 4.173, p < 0.05). Therefore, the full mediation effects were further confirmed.

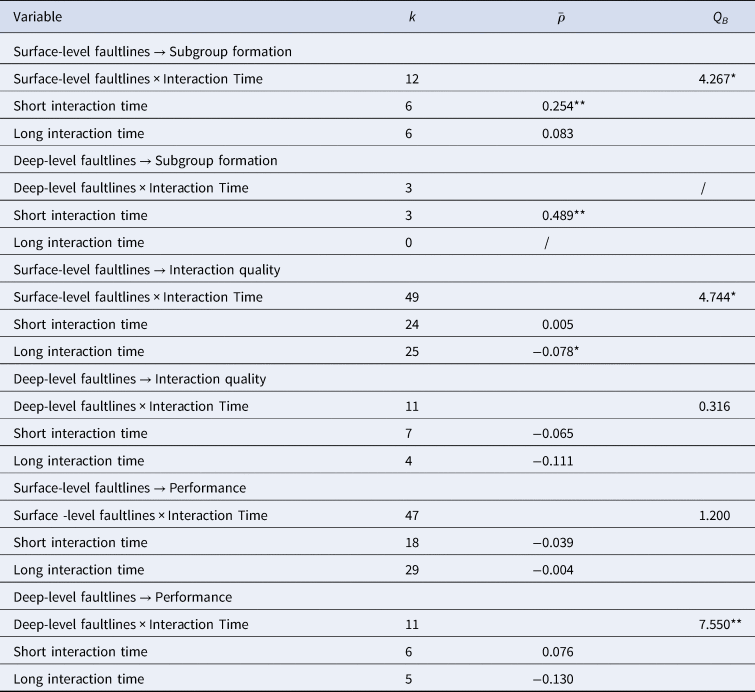

The moderating effects of interaction time

Hypothesis 7 and 8 predicted that the impacts of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines were moderated by the interaction time. Table 6 summarizes the results. Surface-level faultlines show a less positive effect on subgroup formation in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.083, p > 0.05) than in short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$

= 0.083, p > 0.05) than in short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$![]() = 0.254, p < 0.01), and the moderating effect of interaction time is significant (QB = 4.267, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 7a is supported. We found that surface-level faultlines have a negative effect on interaction quality in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$

= 0.254, p < 0.01), and the moderating effect of interaction time is significant (QB = 4.267, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 7a is supported. We found that surface-level faultlines have a negative effect on interaction quality in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$![]() = −0.078, p < 0.05) but a positive effect in the short-term ($\bar{r}$

= −0.078, p < 0.05) but a positive effect in the short-term ($\bar{r}$![]() = 0.005, p > 0.05), which were not in the hypothesized direction. Thus, Hypothesis 7b is not supported. We found that surface-level faultlines exert a less negative effect on team performance in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$

= 0.005, p > 0.05), which were not in the hypothesized direction. Thus, Hypothesis 7b is not supported. We found that surface-level faultlines exert a less negative effect on team performance in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$![]() = −0.004, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$

= −0.004, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$![]() = −0.039, p > 0.05). However, the moderating effect of interaction time is not significant (QB = 1.200, p > 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 7c is not supported. In sum, the moderation effect of interaction time on the effects of surface-level faultlines is supported for Hypotheses 7a.

= −0.039, p > 0.05). However, the moderating effect of interaction time is not significant (QB = 1.200, p > 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 7c is not supported. In sum, the moderation effect of interaction time on the effects of surface-level faultlines is supported for Hypotheses 7a.

Table 6. Moderating effects of interaction time

Notes: k is the number of effect sizes; $\bar{\rho }$![]() is the estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; QB is the between-group heterogeneity statistic; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

is the estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; QB is the between-group heterogeneity statistic; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Limited by research samples, we are unable to test the moderating effects of interaction time in the link between deep-level faultlines and subgroup formation (H8a). Deep-level faultlines show a more negative effect on team interaction quality in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }\;$![]() = −0.111, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;$

= −0.111, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;$![]() = −0.065, p < 0.05). However, the moderating effect of interaction time is not significant (QB = 0.316, p > 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 8b is not supported. We also found that the effect of deep-level faultlines on team performance is more negative in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.065, p < 0.05). However, the moderating effect of interaction time is not significant (QB = 0.316, p > 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 8b is not supported. We also found that the effect of deep-level faultlines on team performance is more negative in long interaction time ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.130, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$

= −0.130, p > 0.05) than in the short-term ($\bar{\rho }\;\,$![]() = 0.076, p > 0.05). And the moderating effect of interaction time is significant (QB = 7.55, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 8c is supported. In sum, the moderation effect of interaction time is only supported for the relationship between deep-level faultlines and team performance (H8c).

= 0.076, p > 0.05). And the moderating effect of interaction time is significant (QB = 7.55, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 8c is supported. In sum, the moderation effect of interaction time is only supported for the relationship between deep-level faultlines and team performance (H8c).

Study 2

Previous empirical studies have found that dormant faultlines could influence team outcomes even when they are not activated into subgroups (e.g., Chrobot-Mason et al., Reference Chrobot-Mason, Ruderman, Weber and Ernst2009). However, Study 1 showed that dormant faultlines work through subgroup formation to negatively impact team interaction quality (see Table 5). And the direct effects of dormant faultlines on team interaction quality were not significant (see Table 3). The inconsistency between previous research's findings and our meta-analysis's results suggests that the direct effects of faultlines on team interaction quality deserve further exploration.

We suppose that the inconsistency could be solved by distinguishing between the social and task forms of faultlines. Researchers have long argued that social faultlines are expected to be harmful, whereas task faultlines are expected to be beneficial to teams (e.g., Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). Chen and her colleagues’ meta-analysis also confirmed that social faultlines decreased team cognition integration, while task faultlines contributed to team cognition integration (Chen, Liang, & Zhang, Reference Chen, Liang and Zhang2019b). Therefore, we decided to take a more nuanced view of faultline itself and examine the effects of surface-level social faultlines, surface-level task faultlines, deep-level social faultlines, and deep-level task faultlines on team social and task interaction qualities.

Hypotheses

The effect of surface-level social faultlines on team interaction quality

Surface-level social faultlines are ‘hypothetical dividing lines’ that divide a group into homogeneous subgroups based on members’ alignment on social category attributes, such as gender, age, race, and nationality (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). Team members’ differences in these characteristics are likely to shape their behaviors through outgroup stereotyping and prejudice, leading to decreased cohesion (Schölmerich, Schermuly, & Deller, Reference Schölmerich, Schermuly and Deller2016) and social integration (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jackson, Shaw and Chung2012), and increased relationship conflict (Choi & Sy, Reference Choi and Sy2010), thus adversely affect team social interaction quality. Whereas surface-level social faultlines may not be directly relevant to team task interaction, the harmful social categorization mechanism will likely disrupt the elaboration of task-related knowledge and information (Van Knippenberg et al., Reference Van Knippenberg, De Dreu and Homan2004). For instance, tension and personal attacks generated from harmful social categorization mechanisms are likely to lead to task conflict (Adair, Liang, & Hideg, Reference Adair, Liang and Hideg2017) and limit information exchanges and knowledge sharing (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009) that are necessary for accomplishing team tasks in teams with surface-level social faultlines.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Surface-level social faultlines have negative effects on social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

We propose that surface-level social faultlines provide a salient basis for subgroup formation. The social categorization processes implied by faultline theory suggest that surface-level social categorical characteristics (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity) are quite accessible because people use these attributes to socialize in their daily lives. In addition, surface-level social categorical differences are likely to serve as the basis of stereotypes and prejudice in the workplace (Stangor et al., Reference Stangor, Lynch, Duan and Glass1992). Thus, surface-level social faultlines have a normative fit. The accessibility and normative fit of surface-level social faultlines provide the basis for subgroup salience, thus contributing to subgroup formation. Once team members perceive the formation of subgroups, the subgroup identity will trigger in-group–out-group biases (Greer & Jehn, Reference Greer and Jehn2007), thus inhibiting beneficial social interactions (Cronin et al., Reference Cronin, Bezrukova, Weingart and Tinsley2011) and creating blocks in exchanging task information (Shemla & Wegge, Reference Shemla and Wegge2019). By extension, we propose that the negative effects of surface-level social faultlines on social and task interaction quality are mediated by subgroup formation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Subgroup formation will mediate the negative effects of surface-level social faultlines on social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

The effect of surface-level task faultlines on team interaction quality

Surface-level task faultlines are formed when ‘hypothetical dividing lines’ separate a team into several subgroups based on visible task-related characteristics, such as educational background, functional background, and tenure. Surface-level task faultlines are typically associated with a larger pool of cognitive resources (i.e., task-relevant skills and information). The extended cognitive resource pool increases the flexibility of team members’ thoughts, making them see the value in their differences (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009), shifting their attention from out-group social prejudice to cross-subgroup cooperation and learning. Thus, surface-level task faultlines will increase team social interaction quality. In addition, team members of different task-related subgroups are willing to utilize all cognitive resources and engage in intensive information elaboration and knowledge sharing (Gibson & Vermeulen, Reference Gibson and Vermeulen2003). Therefore, surface-level task faultlines may operate as healthy divides for task interaction.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Surface-level task faultlines have positive effects on both social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

We propose that surface-level task faultlines may not lead to perceived subgroup formation. Surface-level task skills serve as complementary resources. Thus, team members see the value of task-related differences rather than generating out-group social prejudice based on task-related differences (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto and Thatcher2009). Therefore, surface-level task faultlines do not make sense to the individual's in and out-group perception. As a result, surface-level task faultlines are not salient in predicting the formation of subgroups. Accordingly, the subgroup formation is unlikely to mediate the positive effect of surface-level task faultlines on team interactions.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Subgroup formation will not mediate the positive effects of surface-level task faultlines on social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

The effect of deep-level social faultlines on team interaction quality

Deep-level social faultlines are ‘hypothetical dividing lines’ that divide a team into several subgroups on the basis of the alignment of deep-level characteristics that shape people's social psychology, such as personality, social attitudes, and values. Given the invisibility of deep-level social-related attributes, disputes among team members caused by deep-level social-related differences may cause severe polarization between subgroups, leading to less cohesion and more conflict (Ren, Reference Ren2008). Therefore, deep-level social faultlines can have a more detrimental impact on team social interaction quality. In addition, deep-level personality, attitude, or value differences may lead to disputes in task goals. For example, people with more proactive personalities are more likely to promote task change, while less proactive people will have more passive attitudes toward changing. As a result, a dispute about how to complete a task may occur. Therefore, deep-level social faultlines may also interfere with task interactions.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Deep-level social faultlines have negative effects on both social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

We propose that deep-level social faultlines increase the potential for subgroup formation. Although deep-level attributes (e.g., attitudes, values, and personality) are not easily accessible, they have the normative fit. That is, it is meaningful to develop the cognitive frame of reference of an individual. For example, people with different personalities may have distinct beliefs about team cooperation (Emich, Lu, Ferguson, Peterson, & McCourt, Reference Emich, Lu, Ferguson, Peterson and McCourt2022) and different expectations about task design (Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2015), which provide a salient basis for subgroup formation at the workplace. Combined with the arguments about the negative influences of subgroup formation on team social and task interaction quality, we argue that subgroup formation is likely to mediate the negative effects of deep-level social faultlines on team interactions.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Subgroup formation will mediate the negative effects of deep-level social faultlines on social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

The effect of deep-level task faultlines on team interaction quality

Deep-level social faultlines exist when a team is divided into several subgroups based on members’ alignment on deep-level cognitive features related to team tasks, such as decision-making style, task goal commitment, and task meaningfulness. Differentiated from surface-level task faultlines that indicate diverse cognitive resources, deep-level task faultlines mainly reflect team members’ working styles or attitudes toward tasks. Deep-level faultlines would be more consequential when the attitude object was the task (or task goal) (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Gavin and Florey2002). Members in teams with strong deep-level task faultlines are aware of differences in their way of thought, leading to higher levels of disagreement (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2013) and lower levels of team cohesion and cooperation. As a result, deep-level task faultlines will damage social and task interaction quality.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Deep-level task faultlines have negative effects on both social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

We propose that deep-level task faultlines are salient to increase the potential for subgroup formation. Deep-level task attributes, such as decision-making style, task goal commitment, and task meaningfulness, have a high normative fit. This is because group identification is affected by deep-level beliefs relevant to tasks (Van Knippenberg, Haslam, & Platow, Reference Van Knippenberg, Haslam and Platow2003). Therefore, the normative fit of deep-level task attributes increases the salience of the categorization process, resulting in subgroup formation. Accordingly, we suggest that the subgroup formation mediates the negative effects of deep-level task faultlines on team interactions.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Subgroup formation will mediate the negative effects of deep-level task faultlines on social interaction quality (a) and task interaction quality (b).

Methods

Sample

The sample of Study 2 was extracted from the sample of Study 1. First, we included articles examining the effects of dormant faultlines, which can be clearly classified into social and task faultlines (classifications could be found in the measures of faultlines, 47 articles were excluded). Second, we only included articles providing the correlations between dormant faultlines, subgroup formation, and team interaction quality (16 articles were excluded). Based on the inclusion criteria, 63 articles were excluded (see Figure 1 and Table A1). Finally, 32 articles were included in Study 2's meta-analysis.

Coding

All studies were coded by two authors. The inter-rater reliability coefficients ranged from 0.88 to 0.96, suggesting a reliable coding process.

Meta-analytic techniques

To examine the effects of dormant faultlines on team interaction quality, we followed Schmidt and Hunter's (Reference Schmidt and Hunter2015) meta-analysis methods to calculate the bivariate correlations across studies. As shown in Table 7, we provided the sample size-weighted correlations ($\bar{r}$![]() ), the SD of the correlation (SDr), the weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error ($\bar{\rho }$

), the SD of the correlation (SDr), the weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error ($\bar{\rho }$![]() ), the SD of $\bar{\rho }$

), the SD of $\bar{\rho }$![]() (SDρ), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In addition, we used the MASEM to estimate the mediating effects of subgroup formation between dormant faultlines and subgroup formation (Cheung, Reference Cheung2015). Restricted by the limited sample size, we tested each mediation path separately.

(SDρ), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In addition, we used the MASEM to estimate the mediating effects of subgroup formation between dormant faultlines and subgroup formation (Cheung, Reference Cheung2015). Restricted by the limited sample size, we tested each mediation path separately.

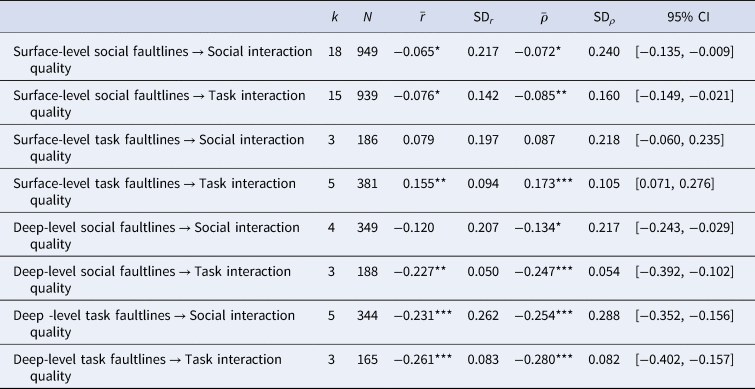

Table 7. The direct effects of faultlines on interaction quality

Notes: k = total number of effect sizes; N = total sample size; $\bar{r}$![]() = sample-size-weighted mean observed correlations; SD r = standard deviation of observed correlations; $\bar{\rho }$

= sample-size-weighted mean observed correlations; SD r = standard deviation of observed correlations; $\bar{\rho }$![]() = estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; SD ρ = standard deviation of $\bar{\rho }$

= estimate of weighted mean correlation adjusted for measurement error; SD ρ = standard deviation of $\bar{\rho }$![]() ; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around $\bar{\rho }$

; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around $\bar{\rho }$![]() ; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Measures

Surface-level social and task faultlines

When testing the effects of faultlines on team interaction quality, we distinguished between surface-level social and task faultlines. Faultlines that are formed from social category attributes (i.e., gender, age, race/ethnicity, nationality) were labeled as surface-level social faultlines; Faultlines that are formed from observable task-related attributes (i.e., education, functional background, tenure, and career experience) were labeled as surface-level task faultlines; Faultlines based on hybrid observable attributes of social category and task-related backgrounds or other observable attributes were labeled as other surface-level faultlines, which were excluded from the meta-analysis in Study 2 (see the coding in Table A1).

Deep-level social and task faultlines

Similarly, when testing the effects of faultlines on team interaction quality, we further distinguished between deep-level social and task faultlines. Faultlines formed from unobserved social psychology characteristics (i.e., relationship values, personality, attitudes, and cultural orientation) were labeled as deep-level social faultlines; Faultlines formed from unobservable cognitive features related to team tasks (i.e., decision-making style faultlines, goal commitment, task meaningfulness) were labeled as deep-level task faultlines; Faultlines based on hybrid attributes of social psychology and task-related cognition or other unobservable attributes were labeled as other surface-level faultlines, which were excluded from the meta-analysis in Study 2 when testing the effects of deep-level social and task faultlines on team interaction quality (see the coding in Table A1).

Social and task interaction quality

We are interested in how social and task faultlines will impact social and task team interaction quality, respectively. Therefore, we further distinguished between social and task interaction quality. On the one hand, social integration quality refers to the status of team members’ social attachment and social relations. We conceptualize social interaction quality as an umbrella of team relationship conflict (inversed term, team trust, team identification, team relational harmony, team cohesion, team social learning, team social/ affective integration, and team cooperation reciprocity. On the other hand, task integration quality refers to the status of team task-related interaction, such as team task conflict (inversed term), knowledge hiding (inversed term), team task learning, team cognitive integration, team information sharing/ elaboration, and team communication (see Table 1). All the variables of team interaction quality are measured subjectively through ratings by team members.

Results

The direct effects of dormant faultlines on team interaction quality

As shown in Table 7, surface-level social faultlines have harmful effects on both social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.072, 95%CI [−0.135, −0.009]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.072, 95%CI [−0.135, −0.009]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.085, 95%CI [−0.149, −0.021]). Thus, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. In contrast, we found that surface-level task faultlines have beneficial effects on both team social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.085, 95%CI [−0.149, −0.021]). Thus, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. In contrast, we found that surface-level task faultlines have beneficial effects on both team social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.087, 95%CI −0.060, 0.235]) and team task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= 0.087, 95%CI −0.060, 0.235]) and team task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = 0.173, 95%CI [0.071, 0.276]). But the effect is only significant on task interaction quality. Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

= 0.173, 95%CI [0.071, 0.276]). But the effect is only significant on task interaction quality. Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

With respect to deep-level faultlines, we found that deep-level social faultlines are harmful to both social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.134, 95%CI [−0.243, −0.029]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.134, 95%CI [−0.243, −0.029]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.247, 95%CI [−0.392, −0.102]). Similarly, deep-level task faultlines also have significant and negative effects on both social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.247, 95%CI [−0.392, −0.102]). Similarly, deep-level task faultlines also have significant and negative effects on both social interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.254, 95%CI [−0.352, −0.156]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$

= −0.254, 95%CI [−0.352, −0.156]) and task interaction quality ($\bar{\rho }$![]() = −0.280, 95%CI [−0.402, −0.157]). Thus, Hypotheses 5a, 5b, 7a, and 7b were supported.

= −0.280, 95%CI [−0.402, −0.157]). Thus, Hypotheses 5a, 5b, 7a, and 7b were supported.

The mediation effects of subgroup formation

Table 8 presents the results of the mediation effects of subgroup formation. The results show that surface-level social faultlines have negative indirect effects on team social interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.038, 95%CI [−0.091, 0.014]) and task interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.043, 95%CI [−0.101, −0.003]) through subgroup formation. But the indirect effect on social interaction is not significant. Therefore, subgroup formation only mediates the negative effect of surface-level social faultlines on task interaction quality, supporting Hypothesis 2b. In contrast, surface-level task faultlines have insignificant indirect effects on team social interaction quality (Indirect effect = 0.020, 95%CI [−0.051, 0.097]) and task interaction quality (Indirect effect = 0.007, 95%CI [−0.049, 0.059]) through subgroup formation. Thus, subgroup formation fails to mediate the positive effects of surface-level task faultlines on team interaction qualities, supporting Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

Table 8. The indirect effects of faultlines on interaction quality through subgroup formation

Notes: Standardized coefficients of direct and indirect effects are reported; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around the indirect effects are present in brackets; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Restricted by the sample size, we were unable to test the indirect effects of deep-level social and task faultlines in a robust wayFootnote 3 (Schmidt & Hunter, Reference Schmidt and Hunter2015). Therefore, we relegate the results to Table A2 and suggest that readers interpret these results with caution. The results in Table A2 show that deep-level social faultlines work through subgroup formation to significantly and negatively impact team social interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.295, 95%CI [−0.412, −0.200]) and task interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.257, 95%CI [−0.365, −0.127]). Similarly, deep-level task faultlines work through subgroup formation to significantly and negatively impact team social interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.208, 95%CI [−0.312, −0.127]) and task interaction quality (Indirect effect = −0.216, 95%CI [−0.316, −0.131]).

Discussion

We developed a framework to bridge dormant faultlines with perceived subgroup formation and team interaction quality. Study 1 looks at how subgroup formation and team interaction quality act as serial mediums through which surface-level faultlines and deep-level dormant faultlines exert effects on team performance. In addition, the meta-analysis in Study 1 examines whether the influences of surface-level and deep-level faultlines grow or shrink over time. Study 2 offers a more nuanced look at the effects of faultlines on team interaction. It conducts meta-analyses to examine how surface-level social faultlines, surface-level task faultlines, deep-level social faultlines, and deep-level task faultlines will impact social and task team interaction quality, respectively.

Research Findings

Relationships among faultlines, subgroup formations, team interaction quality, and team performance

Our results in Study 1 suggest that both surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines lead to the formation of actual subgroups. This confirms the homophily assumption that team members tend to associate with similar members by forming subgroups while giving negative responses to others on another side of the dormant faultline (Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Reagans and Guillory2010). In addition, we go beyond previous works by comparing the impacts of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines on subgroup formation. We also found that deep-level faultlines are more influential in forming subgroups than surface-level faultlines because deep-level faultlines can provide more accurate and straightforward implications about others (Larson, Reference Larson2007).

The serial mediation model

In addition, the results of MASEM in Study 1 indicate that subgroup formation and team interaction quality play vital roles in mediating the effects of surface-level and deep-level dormant faultlines on team performance. Surface-level and deep-level dormant faultlines damage team interaction quality through subgroup formation. These results suggest that the harmful effects of dormant faultlines on team interaction quality heavily rely on the perceived subgroup formation (Mäs et al., Reference Mäs, Flache, Takács and Jehn2013). Further, we find that surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines cannot directly decrease team performance. Instead, they exert negative influences on team performance through subgroup formation and team interaction quality in sequence. These findings indicate that both interaction structure and interaction quality are necessary mediums. By developing a serial mediation framework, this study advances our understanding of dormant faultlines’ effects on team interactions and the final performance. Unlike previous faultline literature that uses dormant faultlines to represent team members’ actual interaction structures, this meta-analysis pulls apart dormant faultlines from team interaction structures and provides a more nuanced view of processes through which faultlines may matter.

The moderating effect of interaction time

Furthermore, by identifying interaction time as a moderator, Study 1 differentiates the influences of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines over time. Our results suggest a tendency that surface-level faultlines show weaker effects on subgroup formation and team performance in long-time interaction than in short-time interaction. In contrast, the influence of deep-level faultlines on team interaction quality and team performance is reinforced in long-time interaction. Although several moderating effects are in hypothesized tendency, they are not significant. We suppose that it is owing to the limited number of studies included in moderation analysis. The moderating effects will be supported if more studies are integrated into future research. Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Gavin and Florey2002) suggested that deep-level diversity becomes more influential than surface-level diversity over time because team members have more time and opportunities to learn from each other. We extended this line of research by confirming that surface-level and deep-level faultlines are also in accordance with the regulation. Therefore, distinguishing between different faultlines helps advance our understanding of how surface-level and deep-level faultlines work separately.

The effects of dormant faultlines on team interaction quality in greater detail

We further distinguished between social and task forms of surface-level and deep-level faultlines in Study 2. We found that surface-level and deep-level social faultlines have similar positive effects on team interaction quality. However, it was interesting to note that surface-level and deep-level task faultlines represented differentiated effects. Surface-level task faultlines are found to be beneficial to team interaction quality, while deep-level task faultlines are harmful to team interaction quality. It is because surface-level task faultlines are formed from educational and functional backgrounds, which indicate a larger pool of domain-relevant skills. Team members are more willing to accept their skill differences, boosting beneficial expression, elaboration, and cooperation (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van Engen and Van Knippenberg2012). Therefore, surface-level task faultlines will contribute to team interaction quality and performance. However, deep-level task faultlines are based on decision-making style, goal commitment, and task meaningfulness, deeply reflecting team members’ working style or attitude toward tasks. All these attributes are rooted deeply in an individual's cognition. Members in teams with strong deep-level task faultlines are aware of differences in their way of thought, leading to higher levels of disagreement and damaging the team function (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2013). Further exploring these additional relationships seems worthwhile, as this would imply that we should distinguish the surface-level and deep-level task faultlines and pay attention to their distinct properties in predicting job-related variables.

Further, the results of mediation effects in Study 2 confirm that dormant faultlines (i.e., surface-level social faultlines, deep-level social, and task faultlines) work through subgroup formation to negatively impact team interaction quality. Especially interesting is that the positive effects of surface-level task faultlines on team interaction quality are not mediated by subgroup formation. So, it is essential to realize that dormant faultlines do not always work through subgroup formation to exert influence. On the one hand, we found that the effects of dormant faultlines on team functioning were exerted through subgroup formation. And this finding is aligned with the perspective of previous research (e.g., Jehn & Bezrukova, Reference Jehn and Bezrukova2010). On the other hand, when it comes to the positive effect of faultlines, surface-level task faultlines have impacts on team interactions, regardless of whether faultlines are activated into subgroups or not.

Theoretical Implications

Our study enriches our understanding of the faultline literature in several ways. It provides cumulative evidence of how surface-level and deep-level faultlines impact subgroup formation, team interaction quality, and team performance. Prior meta-analyses mainly pay attention to the effect of demographic faultlines (e.g., Thatcher & Patel, Reference Thatcher and Patel2012). By distinguishing between different faultline types, we identified the differing effects of surface-level social faultlines, surface-level task faultlines, deep-level social faultlines, and deep-level task faultlines. These differing findings suggest that it is meaningful to divide faultlines into subcategories and to compare their differentiated effects in greater detail.

A second contribution is that we completely test a serial mediation framework from faultlines to team performance. Unlike previous meta-analyses that detect the direct effects of dormant faultlines, this meta-analysis provides a more nuanced analysis of the process through which faultlines may matter. We found that subgroup formation and team interaction quality are essential mediums through which surface-level and deep-level faultlines damage team performance.

Finally, by introducing the moderating role of team interaction time, we further examined the faultlines’ effects over time. The results of moderating analysis provide insight into how the influences of surface-level and deep-level faultlines fade or strengthen in the long term.

Managerial Implications

Meta-analysis offers a solid basis for generating universal managerial implications. First, the influences of deep-level faultlines on team interaction quality and performance grow stronger in the long-term, but the influences of surface-level faultlines become weaker. Thus, in the long run, the challenge managers have is to analyze team members’ deep-level attributes. This is especially meaningful for work teams in the Chinese context, in which people are more veiled and implicit in expressing themselves. To overcome deep-level faultline's negative effects in such a context, managers are recommended to take integration actions to bridge team members who differ in underlying attributes. For example, managers should encourage team members to express themselves openly and resolve problems that arise from deep-level differences in a constructive way.

Second, to avoid the dysfunction of diverse teams, managers should prevent the formation of subgroups. Our meta-analysis indicates that dormant faultlines (i.e., surface-level social faultlines, deep-level social, and task faultlines) mainly exert detrimental impacts on team interaction qualities through the subgroup formation. This is especially true in the Chinese context valuing collectivist culture (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1991), as it is a popular trend for Chinese people to develop small coalitions or cliques in the workplace (i.e., subgroups) to seek support. Thus, we recommend that Chinese managers offer special training to foster team cohesion and highlight the potential value of diversity. This will help reduce out-group prejudice and ultimately prevent the formation of subgroups, such as cliques, factions, and coalitions.

Third, we found that faultlines need not erupt into negative team interactions. Instead, surface-level task faultlines are especially likely to be beneficial. Thus, managers should raise awareness about the potential benefits of differences in task-related attributes. This suggestion is in accordance with the Chinese idiom ‘seeking common ground while reserving differences’. That is, managers should build a team with members differing in the task-related backgrounds and take advantage of surface-level task faultlines by setting common goals and encouraging constructive discussion among team members.

Limitations and future research directions

Our study is still limited in several ways. First, several hypotheses testing were based on a small number of effect sizes, especially in the relationships between deep-level faultlines and subgroup formation. Therefore, analyses based on additional samples will produce more stable results.

Secondly, the correlations that populate the meta-matrix are mainly based on cross-sectional research, so we only use team type (short-term/long-term) as a proxy of interaction time. We cannot fully conclude if faultlines grow or shrink over time because this isn't built off of longitudinal studies. A future meta-analysis that includes only longitudinal research could help clarify the actual changes in the influences of surface-level faultlines and deep-level faultlines over time.

Thirdly, the framework of this meta-analysis separates the subgroup process and team interaction quality. Subgroup formation within a team reflects the overall network interaction structure among team members, whereas interaction quality mainly indicates the exchange content in team interaction processes. However, it has long been recognized that all team interaction processes are embedded in the network structure (Crawford & Lepine, Reference Crawford and Lepine2013). Therefore, the faultline literature should complement team interaction quality with the subgroup structure. For example, future research could examine conflict, trust, and information exchange in the context of inter or intra-subgroup relationships rather than a shared team-level construct (Bezrukova & Jehn, Reference Bezrukova and Jehn2003; Perry, Reference Perry2009). Further, the differentiation between intra- and inter-subgroup interactions would allow us to account for team situations. For example, team members develop mutual trust and common identity within a subgroup, while they distract their attention from developing a high commitment to the whole team. Therefore, the combination of subgroup structure and team interaction quality could help further uncover the team functioning with multiple subgroups.