The names Baby P, Khyra Ishaq and Victoria Climbié are well known to both the general public and health practitioners in the UK. However, we suspect that names such as Michael Gilbert (Reference FlynnFlynn 2011) and Margaret Panting (Reference Vickers and LucasVickers 2004) are less familiar.

Michael Gilbert, who had a history of contact with services, met two ‘friends’ in care who systematically abused him over a period of years. He was beaten daily and tried several times to escape from his abusers, but he was always tracked down and ‘kidnapped’ back into what has been called a life of ‘slavery’ (Reference FlynnFlynn 2011). He was, after a life of torture and abuse, murdered and beheaded.

Margaret Panting was an older woman who died just weeks after moving from sheltered accommodation to live with her son-in-law and grandchildren. She had more than 60 injuries at the time of her death, including razor-blade cuts to her stomach and chest, cigarette burns to her back and armpits, black eyes and bruising so extensive it could not be counted. No one was ever prosecuted, as it could not be established which family member was responsible.

The experiences of Gilbert and Panting resulted in legislation that saw legal and social care systems clearly identify vulnerable adults as a group of people requiring care and support. However, adult protection in the UK remains a complex area of practice where case law is still being made and difficult decisions are often deferred to the Court of Protection. Working with vulnerable adults can be challenging, as individuals who disclose that they are being abused often request that nothing be reported and no action taken. This commonly occurs in cases of domestic violence. So, following the disclosure of abuse by an adult patient with mental capacity, what should the clinician do? What are the grounds for overruling the decision of a competent adult? Would this be the right thing to do? Box 1 discusses a recent ruling in this area, A Local Authority v DL, RL and ML [2010].

BOX 1 Dilemmas in adult safeguarding: what is a vulnerable adult?

The law is fluid in this area. For example, would you think that two adults with no cognitive deficit and who received no physical or mental health support from statutory services would be referred to the Court of Protection and a directive made on their behalf protecting them from their adult son? The son, who had a history of violence and aggression towards his parents, lived with them and was using intimidation to try to exploit them financially.

This was the situation in A Local Authority v DL, RL and ML [2010]. The local authority believed that the elderly couple were at risk of physical, emotional and financial abuse from their son, and made an application on their behalf to the Court of Protection. The Court deemed that, owing to the level of fear that the son induced in his parents, they lacked the mental capacity to make decisions to protect themselves from him. Although in all other areas there was nothing to rebut the couple's mental capacity, their situation was still seen as an adult protection issue.

Safeguarding Adults: The Role of Health Service Practitioners (Department of Health 2011) provides a cogent framework for the support and protection of vulnerable adults that should facilitate a structured response to investigations of adult abuse. It advises that locally agreed adult protection policies be set down for practitioners. Psychiatrists as well as other mental health practitioners have a responsibility to report suspected abuse and may be involved in the investigation of alleged abuse.

Definitions and the development of vulnerable adult legislation

The existing legal frameworks for adult protection in England and Wales are neither systematic nor coherent and have evolved over time (Department of Health 2000, 2009, 2010a,b). Section 47 of the National Assistance Act 1948 affords some protection, but the first ‘modern’ legislation was the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998. This Act has its whistle-blowing roots in the financial dealings of the commercial sector and issues relating to corporate health and safety. However, this is key legislation relating to whistle-blowing in publicly funded care settings such as hospitals and local authority or private establishments, where many people receiving health and/or social care will be vulnerable in one way or another.

The White Paper Modernising Social Services (Department of Health 1998), in conjunction with the report Speaking Up for Justice (Home Office 1998), looked specifically at vulnerable or intimidated people. The documents give detailed guidance on obtaining ‘best evidence’ by providing specialist support and standard guidance for achieving a positive outcome. An important outcome of these two publications is that vulnerable witnesses with mental health problems are now afforded a degree of protection within the courts.

No Secrets (Department of Health 2000) heralded the recognition of safeguarding issues in adults, providing guidance on the development and implementation of multi-agency policies and procedures to protect vulnerable adults from abuse. This document offers a broad definition of a ‘vulnerable adult’ as a person:

‘who is or may be in need of community care services by reason of mental or other disability, age or illness; and who is or may be unable to take care of him or herself, or unable to protect him or herself against significant harm or exploitation’ (para. 2.4).

The reader may question the need for the qualifying statement regarding community care services, which would appear to limit the scope of the definition.

No Secrets acknowledges some of the difficulties in defining abuse, and describes it as:

‘a violation of an individual's human and civil rights by any other person or persons’ (para. 2.5).

This basic definition is then expanded:

‘Abuse may consist of a single act or repeated acts. It may be physical, verbal or psychological, it may be an act of neglect or an omission to act, or it may occur when a vulnerable person is persuaded to enter into a financial or sexual transaction to which he or she has not consented, or cannot consent. Abuse can occur in any relationship and may result in significant harm to, or exploitation of, the person subjected to it’ (para. 2.6).

No Secrets made explicit the best practice principles for working with vulnerable adults and its aim was to ‘close a significant gap in the delivery of [human] rights’ (Department of Health 2000: para. 1.1). The rights and freedoms within the Human Rights Act 1998 that are especially germane include: the right to life; freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment; the right to liberty and security; the right to respect for private and family life; and the right to protection from discrimination.

Adult protection and safeguarding also aims to limit the opportunity for abuse to occur, and the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006, in conjunction with the Independent Safeguarding Authority, has actively sought to bar inappropriate people access to vulnerable groups. The Act was set up as a result of the public inquiry on child protection procedures following the murders of Jessica Chapman and Holly Wells in Soham (Reference BichardBichard 2004). Since December 2012, this role has been managed by the Disclosure and Barring Service.

Other key legislation linking to the protection and support of vulnerable adults in the statutory, third (voluntary) and private sectors include the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 and the Health and Social Care Act 2008.

Other countries have similar legislation to support and protect vulnerable adults. For example, in Scotland:

-

• Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000

-

• Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004

-

• Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007

-

• Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007: Code of Practice (Scottish Government 2008);

and in Northern Ireland:

-

• Protection of Children and Vulnerable Adults (Northern Ireland) Order 2003

-

• Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups (Northern Ireland) Order 2007

-

• Mental Capacity (Health, Welfare and Finance) Bill (under discussion, and it is hoped will be enacted in 2013/14).

How common is abuse of adults?

The official statistics and surveys discussed in this section probably underestimate the true prevalence of abuse. The figures are likely to be influenced by how individual authorities carry out their duties under the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006. Nevertheless, the available data help identify those who may be at highest risk.

Between October 2009 and March 2010, there were 96 000 reported cases of abuse of vulnerable adults in England, although 14 000 individuals featured at least twice (NHS Information Centre 2011). Women were more likely to be referred (62% of cases) and 61% of cases were for persons over the age of 65. The group most likely to be reported were those with a physical disability (50%), then intellectual disability (21%), mental health needs (20%) and those with substance misuse (1%).

The most common type of abuse was physical (30%), then neglect (23%) and financial abuse (20%). Emotional or psychological abuse accounted for 16% of referrals and sexual abuse for 6%. Abuse was most likely to occur at home (41%) or in a care home (34%). Given these settings, it may not be surprising that family members were perpetrators in 25% of cases, and care home staff in another 25%. Standardising for age and gender revealed regional variations in reported abuse, such as rates of 6% in the South East and rates of between 13 and 14% in the North and Midlands.

Mind (2009) were commissioned by the Department of Health to investigate the experience of abuse by people with mental health problems. Although the response rate was very low (3.6%), focus group information allowed issues to be explored in greater detail. The headline result was that ‘84% of respondents felt that they were vulnerable or at risk of abuse some or all of the time’. Respondents also described a systematic failure of authorities to respond effectively to their concerns.

Psychiatric wards have high rates of physical and other abuse and there is the perception that such abuse is both tolerated and expected (Reference FaulknerFaulkner 2005). Abuse is also common in the community, with 71% of respondents in one survey (Mind 2007) reporting being victimised on at least one occasion in the previous 2 years; 25% reported being targeted in their own home.

Recognition and types of abuse

Recognising abuse is potentially difficult. It will vary with the type of vulnerability the adult has and the type of abuse perpetrated, but one of the key elements in identifying abuse is to look beyond first impressions. Abuse is more likely to be recognised if the professional is aware of the possibility of abuse and has a reasonable index of suspicion.

Box 2 highlights common ways in which professionals become aware of potential abuse and Table 1 gives signs for particular types of abuse. A victim may be subjected to multiple forms of abuse and the identification of abuse of one type should alert the professional to explore other risks. People with dementia or severe intellectual disability may not be able to articulate their distress and the only clues may be a change in behaviour or observations made during a professional visit.

TABLE 1 Types, examples and signs of abuse

BOX 2 How might you become aware of abuse?

-

• A vulnerable adult may tell you about the abuse

-

• A friend, family member or somebody else may tell you something that causes you concern

-

• You may notice injuries or physical signs that cause you concern

-

• You may notice either the victim or the abuser behaving in a way that gives you a ‘gut feeling’ that something may be wrong

Although fabricated or induced illness (so-called Munchausen's syndrome by proxy) is associated with child abuse, it can be perpetrated on adults. For example, we have seen a case of a wife presenting her husband, who had dementia, for urinary catheter changes on a daily basis, and we found evidence that the problems were the result of tampering. Another case involved a man who underwent serial investigations and hospital admissions for nocturnal fits which were described in detail by his wife. She later confessed that she had lied about them.

Perpetrators, settings and victims

Perpetrators of abuse do not fit one stereotype. Potential abusers could be a partner, child, relative, friend, neighbour, stranger, paid or voluntary carer, as well as staff of statutory bodies such as health and social care workers. Vulnerable adults can themselves be perpetrators of abuse. For example, a man with dementia may pose a threat to other residents in his care home if he develops sexually disinhibited behaviour or becomes agitated. Victims of domestic violence may themselves become perpetrators of abuse.

It is also worth remembering that abuse may occur as a result of ignorance or limited coping strategies and it may not be perceived as abuse by the perpetrator. For example, the physical restraint of a disturbed individual may go beyond what is appropriate, or punitive ‘behavioural strategies’ may be used for the victim's ‘own good’.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 can cause confusion regarding this, as Section 5 (‘Acts in connection with care or treatment’) allows for restraint and reasonable force to be used to protect a person believed to lack mental capacity and to prevent them from risk of harm. However, Section 6 of the Act imposes limitations to Section 5. For example, any restraint must be in connection with the person's care, in their best interests and proportionate to the likelihood of injury or harm, and reasonable steps must have been taken to establish mental capacity. Section 5 also safeguards people who appropriately intervene in such a manner from criminal or civil liability.

The principles of safeguarding

Safeguarding Adults (Department of Health 2011: pp. 12–13) describes six fundamental principles for improving the quality of health and social care interventions in safeguarding. These principles, which are described below, provide a structure for improving outcomes for vulnerable adults.

Empowerment – presumption of person-led decisions and consent

Decision-making capacity

‘Adults should be in control of their care, and their consent is needed for decisions and actions designed to protect them’ (Department of Health 2011: p. 12). This is one of the fundamental differences between safeguarding adults and children. Mental capacity is decision specific and is presumed to be present unless it is demonstrably not. Clinicians must be aware of the criteria for assessing capacity (Reference Biswas and HiremathBiswas 2010). Capacity is defined by the Mental Capacity Act in terms of its absence: ‘a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’ (Mental Health Act: Section 2). If a person lacks capacity then this should be clearly documented, together with the rationale for decisions made on that person's behalf. Of course, individuals who lack capacity should still be involved in decision-making where appropriate.

Although the Mental Capacity Act is fundamental in assessing capacity, it is the courts that ultimately determine where the line is drawn in contentious cases. Professionals may be aware of situations where an individual has capacity, but their ultimate ability to give free and valid consent is impaired by a variety of factors (Box 3). Such factors may affect the person's decision-making ability, but this does not remove their right to make decisions, and professionals should try to mitigate or minimise their effects.

BOX 3 Factors that might impair capacity because of duress or undue influence

-

• Fear of reprisal or abandonment

-

• Eroded confidence, e.g. secondary to mental ill health

-

• Sense of duty or obligation

-

• Cultural beliefs and customs

-

• Religious beliefs

-

• Significant power imbalance in a relationship

Risk to others

Assessing an individual's risk to others can be a complex task and may overlap with public interest. Multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA) may be an appropriate statutory approach in the management of high-risk scenarios, as might multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs) for serious domestic violence. The Department of Health's (2011) guidance opines that risk cannot be eliminated, nor is it necessarily desirable to do so, and that responses to risk should be proportionate.

Clinicians have obligations under the Children Act 1989 and should be aware that a person who is causing harm to an adult may also be a risk to a child. The main obligation imposed by the Children Act is that the child's needs are paramount. In relation to children,

‘“harm” should be taken to include not only ill treatment (including sexual abuse and forms of ill treatment which are not physical), but also the impairment of, or an avoidable deterioration in, physical or mental health; and the impairment of physical, intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development’ (Department of Health 2000: Section 2.18).

Although a capacitous individual may elect to put themselves at risk, if this might adversely affect children in their care it would contravene the Children Act. For example, they may knowingly choose a relationship with a person with a history of offences against children. (It should also be remembered that adults with capacity can make unwise or eccentric decisions, as described in Section 1 (4) of the Mental Capacity Act.) Legal restrictions may be relevant if a person's action or planned action is unlawful.

Protecting the professional

Safeguarding decisions should respect the person's age, culture, beliefs and lifestyle, subject to the exceptions described above. Documentation is important and the professionals involved in safeguarding should record their decisions, including why the option chosen is the least restrictive. This will need to be justified by describing the alternatives explored and disregarded, as well as the views of those consulted.

A potential source of conflict in adult safeguarding is the professional's duty of care and their profession's standards of good practice. Failing to meet these may lead to concerns regarding negligence. Reference KemshallKemshall (2009), quoted in Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained (Department of Health 2010b), offers guidance on demonstrating that the professional's duty of care has been met (Box 4).

BOX 4 Duty of care checklist

-

• All reasonable steps have been taken

-

• Reliable assessment methods have been used

-

• Information has been collated and thoroughly evaluated

-

• Decisions are recorded, communicated and thoroughly evaluated

-

• Relevant policies and procedures have been followed

-

• Practitioners and their managers adopt an investigative approach and are proactive

Protection – support and representation for those in greatest need

‘There is a duty to support all patients to protect themselves’ (Department of Health 2011: p. 12). The Mental Capacity Act recognises this need and provides wide-ranging legal powers to promote unbiased representation.

The Court of Protection is usually the final arbiter in contentious cases. Less difficult or far-reaching decisions can be reached by use of an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) service. This ensures representation of a vulnerable person where, for example, critical decisions about care are required, conflict is evident in a family, or agencies disagree about management and what would be in the person's best interests.

Deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS)Footnote † can also assist in safeguarding a vulnerable adult (who lacks mental capacity). These offer an objective and independent ‘best interests assessment’, which seeks to apply the least restrictive principles to promote the welfare of the person.

A lasting power of attorney (LPA) enables a nominated individual (the ‘attorney’) to make decisions related to both finances and personal welfare, including consent to medical treatment, for an individual who lacks decision-making capacity. All actions taken must be in the individual's best interests.

Prevention

‘Prevention of harm or abuse is a primary goal’ (Department of Health 2011: p. 12). Primary prevention of harm or abuse will involve public education and government policy. At a personal level, prevention involves helping the individual to reduce risks of harm and abuse. This might entail direct work with victims or their carers. It might also require professionals to act as advocates for their patients. For example, a care coordinator might liaise with a surgical unit on behalf of a patient who has significant communication difficulties. The care coordinator's advice regarding these difficulties might reduce the likelihood of disturbed behaviour during treatment.

Prevention also involves reducing the risk of neglect and abuse within health services. Inquiries such as those into Winterbourne View hospital (Department of Health 2012) and Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust (Reference FrancisFrancis 2013) have identified a number of factors that increase the risk of institutional abuse. These include an inward-looking culture, poor environment, low staffing levels (including high levels of ‘bank’ or casual staff) and poor supervision.

Proportionality – proportionality and least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented

‘Responses to harm and abuse should reflect the nature and seriousness of the concern. Responses must be the least restrictive of the person's rights and take account of the person's age, culture, wishes, lifestyle and beliefs’ (Department of Health 2011: p. 12). These principles are reflected in key legislation supporting individual rights, such as the Human Rights Act. Some people, because of their significant vulnerability, require additional safeguards such as those set out in the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007). As Reference Curtice, Bashir and KhurmiCurtice et al (2011) point out, case law clarifies the meaning of proportionality: the State ‘should not use a sledgehammer to crack a nut’.

The active participation of the individual in any assessment process, whether or not they have capacity, can help in determining outcomes and ensuring that a proportionate response to risk and risk management is made. The components identified above are transferable in work with vulnerable people within a health or social care setting and provide the basis for interventions that follow ‘best practice’.

Partnerships – local solutions through services working with their communities

‘Safeguarding adults will be most effective where citizens, services and communities work collaboratively to prevent, identify and respond to harm and abuse’ (Department of Health 2011: p. 13).

It is clear that investigation of allegations of abuse is likely to be multi-agency/multidisciplinary, involving the National Health Service (NHS), Social Services, other local authority agencies and the police. Legal opinions may also be required from the relevant authority. Given the fluid nature of the law in this area, it is perhaps not surprising that when health and social service staff consult their respective legal advisors the resulting advice is not always in agreement.

Accountability – accountability and transparency in delivering safeguarding

Partnership working requires partners to be open and transparent with each other about how safeguarding responsibilities are being met. It should be remembered that services are accountable to patients, the public and their governing bodies. Publication of statistics and audit allows comparisons of how safeguarding is being delivered in different areas.

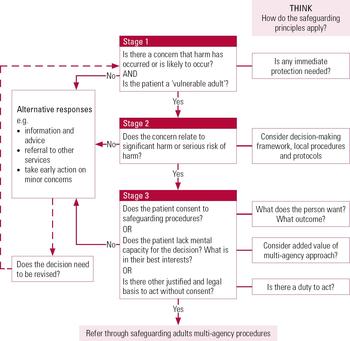

Investigating allegations of abuse

The principles of safeguarding also provide the basis for investigation of potential abuse (Fig. 1). A key step is being able to identify abuse and decide on the necessary intervention on the basis of an assessment of risk. If abuse has occurred or is reasonably suspected, the legislative framework supplies the legal context for investigating it. The police are central to the investigation, as criminal action against those responsible may result.

FIG 1 Decision-making in safeguarding vulnerable adults (adapted from Department of Health 2011: p. 29).

An investigation might be led by the police or by a health or social care professional. The parameters and processes of the investigation are usually framed within local adult protection procedures to which local agencies have agreed. The local inter-agency policy will normally define key roles, procedures and questions such as:

-

• Who is to be the lead investigator – multi-agency or single agency?

-

• Which agency is best placed to lead? Police, healthcare or social care?

-

• What is the allegation?

-

• Does the allegation meet the threshold for investigation?

-

• Does the person have mental capacity?

-

• Does the person have a mental disorder?

-

• Should a strategy discussion take place immediately to consider risk management and ensure the person's safety?

-

• Should an investigation review meeting be arranged so that the person and partner agencies can discuss the issues and formulate a protection plan with specific actions and time scales recorded against participants' names?

-

• Should an outcomes conference be convened following the investigation, to confirm the facts and actions that might be required to keep the person safe?

Ongoing monitoring and review should continue until the level of risk has reduced to low or the risk has been removed.

Once the investigation is concluded the agreed protection plan should be incorporated in the person's care plan (in England and Wales), where it can be reviewed regularly.

Statutory legislation

Psychiatrists working with vulnerable adults should already be familiar with relevant statutory legislation. In England and Wales, the Mental Health Act overrides the Mental Capacity Act, and where the criteria of the Mental Health Act are met this must be the legislation used.

Certain provisions of the Mental Health Act may be particularly useful. The use of guardianship (Section 7) may help reduce risk for vulnerable adults (Box 5). Section 115 provides powers for an approved mental health professional (AMHP) to enter and inspect premises (other than a hospital) in which a mentally disordered patient is living if there is reason to believe that the patient is not receiving proper care. Under Section 127(1), the ill-treatment or wilful neglect of patients by hospital or nursing home staff can lead to financial penalty and/or 5 years' imprisonment. This also includes acts of omission, either intentional or unintentional. Successful prosecutions have already been made. (This new criminal offence of ill-treatment or neglect was introduced into the legislation with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Section 44) and added to the Mental Health Act in the 2007 amendments.)

BOX 5 Proportionality and safeguarding

A 72-year-old man with mild dementia who was felt to lack mental capacity to make decisions about his care needs and finances was removed from his home by his daughter and taken to live with her. His son had concerns about this, because of his sister's chaotic lifestyle. She lived in a one-bedroom flat with two large dogs and was known to the substance misuse team. She was consistently refusing to allow relatives and professionals access to her father. The local authority applied to a magistrates' court for a warrant to enter the flat under Section 135 of the Mental Health Act, as there were concerns that the father was being exploited and not receiving care and support. He was found to be in an unkempt and dishevelled state, although not distressed. He was sleeping with the two dogs on the settee and the environment was unsanitary. He was removed to a place of safety and eventually placed in residential care under Section 7 of the Mental Health Act (guardianship).

This was a proportionate response to the identified risks of significant harm arising from concerns about neglect, exploitation and the daughter keeping her father effectively as a prisoner. Implementation of Section 7 provided effective and efficient management. This included a compromise with the father that allowed him contact with his daughter, which he wanted. This meant continued exposure to some risk, but with the protection of a safe place to live and monitoring safeguards in place.

The Mental Capacity Act, with the Court of Protection, the Office of the Public Guardian and lasting powers of attorney, provides a clear framework that offers vulnerable adults who lack mental capacity some significant safeguards. In addition to authoritatively defining capacity, the Act dictates that decisions made must be in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity. For particularly complex decisions, best interests case conferences that include key stakeholders can be held (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007).

The Court of Protection can make decisions regarding, for example, where the person should live and who can and cannot have contact with them. It can also give consent to treatment and direct the local authority to manage their care (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007).

The Health and Social Care Act 2008 requires that all health and social care service providers are registered with the Care Quality Commission (CQC). The Act empowers the CQC to investigate any concerns that arise about care. It has the right to inspect premises, examine written and electronic records, and impose sanctions, should these concerns be proven.

As a result of the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006, Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) checks are carried out pre-employment for those working with vulnerable people. Following recent reorganisation, these checks are now undertaken by the Disclosure and Barring Service.

Outcomes

Between October 2009 and March 2010, the most common outcome following a preliminary case review in England was no further action (accounting for 31% of all the outcomes recorded) (NHS Information Centre 2011). Next came increased monitoring (26%), ‘other’ (13%) and community care assessment and services (10%). ‘No further action’ is also the most likely outcome following formal investigation (34%) or continued monitoring (17%). Unfortunately, a more qualitative account of ‘no further action’ is unavailable, but our own experience would suggest that this outcome results if there is no evidence of abuse or the issue has been resolved through the investigation.

Changing culture: training and good practice

The first issue in terms of changing culture is for professionals to recognise what constitutes the abuse of adults and that such abuse is as unacceptable as abuse of children. Abuse can occur in any environment, and professionals may need to be reminded that it has and does occur in NHS, private and local authority accommodation, as well as in the domestic setting.

It is critical that all staff receive training in relation to adult safeguarding. Many English NHS trusts and local authorities run joint training sessions on vulnerable adults and child protection. These are usually mandatory and provide induction into these issues at every grade and level within the organisation. Advanced training should be given to staff undertaking lead roles in adult protection investigations and to chairs of vulnerable adult investigation review meetings and outcomes conferences.

Conclusions

Adult protection remains high on the political agenda, and clinicians will know from their own experience that within statutory, private and third sectors there is a firm and clear commitment to ensuring that the abuse of adults is recognised, reported and appropriately dealt with. Annual statistics show an incremental rise in reporting (NHS Information Centre 2011), which is encouraging as it demonstrates increased awareness. To keep this momentum, mental healthcare professionals should review their local policies and procedures and maintain a high degree of vigilance for abuse.

Irrespective of differing legislation or policy, the main impetus of adult protection is to keep highly vulnerable people safe from exploitation and harm.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Catherine Campbell for her helpful comments on earlier drafts.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The Department of Health's basic principles of adult safeguarding include:

-

a disempowerment – no presumption of person-led decisions and consent

-

b protection – support and representation for those in least need

-

c prevention

-

d involvement of the police in all investigations

-

e statutory definition of the lead agency in investigations.

-

-

2 A practitioner's performance in adult safeguarding may be improved by:

-

a ignoring local adult protection procedures

-

b being unaware of local reporting requirements

-

c attending a training session

-

d not considering the possibility of adult abuse in their daily practice

-

e assume that it is the responsibility of Social Services.

-

-

3 The following legislation may be relevant to safeguarding vulnerable adults:

-

a Mental Capacity Act 2011

-

b Mental Health Act 1957

-

c Young Persons Act 2011

-

d Environmental Protection Act 1990

-

e Human Rights Act 1998.

-

-

4 Signs of abuse may include:

-

a explained bruising

-

b a happy demeanour

-

c repeated emergency medical presentations

-

d wearing appropriate clothing for the person's culture

-

e good relationship with caregivers.

-

-

5 Institutional abuse is said to be associated with:

-

a highly trained staff

-

b use of permanent staff

-

c high staffing levels

-

d rigid treatment regimens

-

e good leadership.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | c | 3 | e | 4 | c | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.