Migration to high-income countries is linked to increased risk of non-communicable diseases (Reference Agyemang and van den Born1). Immigrants from low- and middle-income countries moving to high-income countries experience an abrupt change from a more traditional food environment to a modern, industrialised one(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2) and over time they suffer from higher rates of many negative health outcomes, including obesity, type 2 diabetes and other diet- and metabolism-related chronic diseases, often at a younger age(Reference Agyemang and van den Born1,Reference Gilbert and Khokhar3,Reference Hjern4) . Immigrants have reported abrupt changes in the social and environmental structure including lack of time, lack of social relations, more stress, children’s preferences, taste, food insecurity and lack of access to traditional foods leading to having a less healthy lifestyle after migrating(Reference Mellin-Olsen and Wandel5,Reference Popovic-Lipovac and Strasser6) .

The food environment can be considered as the interface between the food system and consumers’ food acquisition(Reference Turner, Aggarwal and Walls7). Availability of unhealthy foods has been linked to obesity more consistently than availability of healthy foods(Reference Cooksey-Stowers, Schwartz and Brownell8) as observed through the presence of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods(Reference Congdon9,Reference Rose, Bodor and Hutchinson10) and greater access to unhealthy food outlets(Reference Giskes, van Lenthe and Avendano-Pabon11); this availability has also been linked to type 2 diabetes(Reference Mezuk, Li and Cederin12). Accessing foods is a complex dynamic of availability, accessibility and social, cultural and material conditions(Reference Giskes, Kamphuis and van Lenthe13,Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian14) . Additionally, perceived access has been found to relate more to dietary behaviour than to objective measures such as distance to stores(Reference Giskes, Kamphuis and van Lenthe13–Reference Nakamura, Inayama and Harada15). Residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods has been consistently associated with obesogenic dietary behaviour and higher rates of diet-related non-communicable diseases(Reference Giskes, van Lenthe and Avendano-Pabon11,Reference Bennet, Johansson and Agardh16) . However, living in a neighbourhood with a high immigrant density has been found to be protective against the dietary changes acquired through acculturation(Reference Zhang, van Meijgaard and Shi17).

How interactions take place with the food environment are not well understood, specifically the interactions between immigrants, the food environment in the host countries and their potential impact on acquisition of food. An important step in characterising these interactions is to synthesise what is known about immigrants and their food environment. A scoping review was therefore conducted with the aim to map and characterise the interactions between the food environment and immigrant populations from low- and middle-income countries living in high-income countries, as well as identify research gaps.

Methods

A scoping review protocol was developed and revised by the research team, and the final protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework on 29 January 2021 (https://osf.io/vzx57). We performed the scoping review using the methodological framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley(Reference Arksey and O’Malley18) and further developed by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien19). The review followed five key phases: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. The reporting is described as per the PRISMA-ScR guidelines(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin20).

Identifying relevant studies and study selection

Relevant literature on the food environment and immigrants in high-income countries published in English between 1 January 2007 and 14 May 2021 was eligible for inclusion, the latter being the date of the last search. Grey literature was subsequently not included since initial searches and reading found negligible grey literature on the subject. Three electronic databases (EMBASE, PubMed and Web of Science) were used as primary search sources. A search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian through Uppsala University Library. Key words relevant to food environment and immigrant population were formed into a search string (see online Supplemental Table 1). Backward and forward snowballing and hand searches were performed to identify additional articles.

Two reviewers carried out the initial search and used the Rayyan QCRI for independently screening titles and abstracts(Reference Ouzzani, Hammady and Fedorowicz21). At the title and abstract screening phase, only articles related to migration from low- and middle-income countries to high-income countries, coupled with aspects relating to the food environment, were included (see online Supplemental Table 2). The full-text screening was also performed by two reviewers; a simple data collection form was developed to assess the relevance of the articles in order to facilitate consistency in the inclusion and exclusion process. Disagreements on study selection were resolved by consensus and discussion and when necessary, consulted the third reviewer. No critical appraisal was carried out on the studies as scoping reviews do not usually include this step(Reference Lockwood, dos Santos and Pap22).

Charting the data

In this stage each of the eixty-eight articles were read thoroughly, followed by charting of the data extracted based on the PICO model (population, intervention, comparison, outcome of interest) (see Table 1). Each of the two reviewers charted half of the articles and reviewed one another’s charting.

Table 1 Charting form of included articles

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

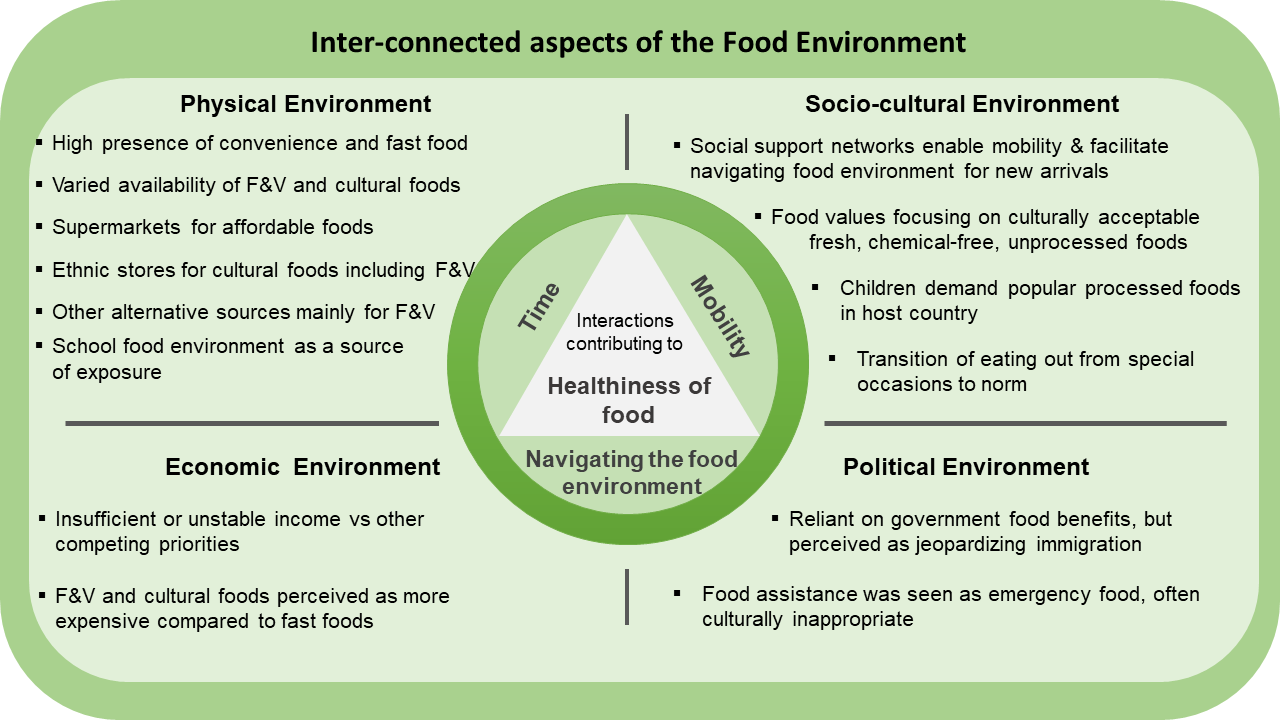

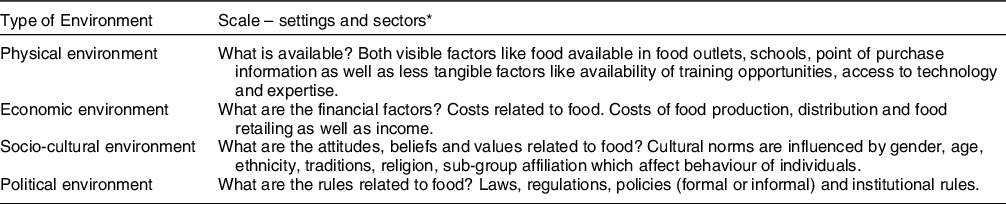

The extracted data from the results and discussion sections of the included papers were synthesised. This was done inspired by the ‘Best fit’ framework synthesis, a practical method where data are coded into a priori themes, as well as additional themes for data that do not fit into the framework(Reference Booth and Carroll23). We used the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework to interpret the data, with the following a priori themes: physical environment, economic environment, socio-cultural environment and political environment (see Table 2)(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza24). The ANGELO framework is further divided into micro and macro settings, which we did not use in our analysis as the full-text reading of the selected articles revealed that there was very little on the macro scale. Additionally, where data seemed to belong to more than one of the themes, overarching themes were created. The findings relating to each theme were discussed among the team to improve trustworthiness and to reach consensus.

Table 2 Analysis grid for environments Linked to obesity (ANGELO framework) from Swinburn et al. (Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza24)

* In this review, the settings (micro) and sectors (macro) were not separated. This slightly modified ANGELO framework was used for the analysis.

Results

A total of 2835 records were identified in the initial search and after removal of duplicates, 2103 were screened for title and abstract. Backward, forward snowballing and search in google scholar identified eighty-seven additional articles. In total, 228 articles were eligible for full-text screening (see Fig. 1). Finally, a total of sixty-eight articles were eligible for inclusion. Out of sixty-eight articles, the vast majority (forty five) studied populations living in the USA(Reference Bojorquez, Rosales and Angulo25–Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69); ten were based in Canada(Reference Amos and Lordly70–Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79), seven from Australia(Reference Addo, Brener and Asante80–Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86), three from the UK(Reference Lofink87–Reference Fraser, Edwards and Tominitz89), one from Switzerland(Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90), one from Norway(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2) and one from the Netherlands(Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91). The immigrant groups were from Asia, Africa, Middle East, South and Central America and the Caribbean. Of these, forty two were qualitative, nine were quantitative and seventeen were mixed methods studies. Around 35 % of the studies included only women and the remaining were mixed participant populations.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of literature search and selection

An overview of the sixty eight included studies is shown in Table 1, and the results are presented below according to themes from the ANGELO framework, followed by overarching themes.

Physical environment

Out of sixty-eight included articles, fifty two had data pertaining to the physical environment.

Host country food environments

In the low-income neighbourhoods where immigrants resided, there was easy access to fast food outlets and unhealthy food items in stores(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Jacobus and Jalali57,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Lofink87,Reference Fraser, Edwards and Tominitz89,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Fruits and vegetables were reported as being of low quality and of limited variety in the neighbourhood stores(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38) . In some areas with a high proportion of immigrants, there were ethnic stores that catered to their food preferences(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74,Reference Lofink87) , while others travelled greater distances either to access these or for greater variety or lower prices(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84) . In general, immigrants living in urban areas had better access to stores, as well as cultural foods, than those in rural areas(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) where access to a car was necessary(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69).

Availability of specific food types

Immigrants reported that there was an overall abundance of food in the host country(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Amos and Lordly70,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) ; produce was always available and not just seasonally as they were used to(Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Wilson, Renzaho and McCabe83,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell88,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Eating a healthy diet based on fresh foods was challenging as they were more difficult to access, particularly in smaller metropolitan areas that depended on seasonal produce(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69) while neighbourhoods were filled with stores providing unhealthy options(Reference Park, Quinn and Florez41,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61) . In larger cities and places where immigrants had resided over a longer period, it was easier to access cultural foods(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84) and for early arrivals from different ethnic groups it was more of a struggle(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2). Accessing halal foods in order to eat according to Islamic religious principles was essential for Muslim immigrants(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Moreover, the articles referred to an increased availability of cultural including halal foods over time(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Leu and Banwell85,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . In different settings, some groups had an easier time than others to find their cultural foods, though many found it a challenge(Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Sastre and Haldeman68,Reference Amos and Lordly70,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . There was a lack of familiarity and variety thereof(Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86). Halal foods would have to be accessible for meat and meat-containing products to be considered as ‘available’ for consumption, in the same way as unfamiliar fruits and vegetables tend to be ignored(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Feeling uncertain about the content of food items, particularly in the early period, meant excluding them, reducing available options(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2).

Avenues for sourcing food

Large supermarkets were considered as the basis for most immigrants’ food shopping – a one-stop shop to buy a variety of good quality, affordable food including produce in a clean environment(Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Franzen and Smith51,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) , though some felt uncomfortable in the ‘sterile’ environment(Reference Jacobus and Jalali57). With demand, supermarkets increased the amounts of cultural foods they sold(Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91). These supermarkets were often further away, requiring transportation(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29), and local stores were considered more expensive and of lower quality(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Sharif, Albert and Chan-Golston59) . In order to acquire foods, participants typically visited several stores or food sources(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Yi, Russo and Liu60,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) particularly ethnic stores to supplement what they could procure at the supermarket.

Ethnic stores were clustered in areas where immigrants resided(Reference Franzen and Smith51), and they were frequented to purchase culturally specific foods including fruits, vegetables, meat and other ingredients(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Franzen and Smith51,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Sharif, Albert and Chan-Golston59,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) . The ethnic shops had a personal connection with customers(Reference Burge and Dharod27) and by speaking the language of customers, helping them to understand product labelling(Reference Yi, Russo and Liu60,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79) . Immigrants who had poor host country language skills, as well as those with religious dietary restrictions, preferred to rely on the ethnic stores(Reference Jacobus and Jalali57,Reference Yi, Russo and Liu60) and others lacked skills to buy foods outside of halal stores(Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79). In this way, they could be more independent and shop on their own(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). Ethnic stores were found to fill a gap in the provision of healthy food in areas deemed food deserts(Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52,Reference Fraser, Edwards and Tominitz89) .

Other food sources were frequented primarily for fresh produce; these included farmers’ markets(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) , Pulgas (flea markets), fruit and vegetable stands, vendors, farms, livestock markets as well as family, friends or neighbours(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Sharkey, Dean and Johnson44,Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75) or by foraging for food(Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75) . Many immigrants cultivated or longed to grow their own food again(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73) , as a way to access tastier, more nutritious, culturally appropriate fresh produce they could trust, while saving money(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) .

School food environment

Children of immigrants were introduced to host country foods including highly processed foods through school food(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Blanchet, Sanou and Batal72,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) , which also led to a change in preferences(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69) . For packed lunches, mothers soon stopped sending traditional food as they came back uneaten and learnt how to make lunchboxes in the way of the host country(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Reasons for not taking traditional foods as a school lunch included lack of facilities to heat up food, not wanting to spill, food allergies, food odors, short periods to eat, and importantly, children wanting to fit in(Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71–Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73).

Economic environment

Out of sixty-eight included articles, forty had information pertaining to the economic environment.

Socio-economic circumstances and food access

In general, immigrants had limited incomes(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo36,Reference Hammelman37,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74,Reference Vahabi and Damba76) ; the first 2 years were particularly precarious, though the financial situation of immigrants improved over time(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74). Poverty meant that there were many competing needs and these were difficult to manage(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo36) . Rent and utilities needed to be prioritised over other things, such as food(Reference Hammelman50), and likewise food was prioritised over health and other costs(Reference Hammelman37). In addition, those with families needing support in the home countries, sent remittances, further reducing their disposable income(Reference Sano, Garasky and Greder67). More than half the monthly budget was spent at the beginning of the month on provisions(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64).

Low incomes were centrally linked to food insecurity(Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo36,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Hammelman50) and food decisions are majorly impacted by income(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78), leading to a lack of control over food choices(Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) . Food prices were often high in relation to the income of immigrants(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74), which was a hindrance for buying food(Reference Peterman, Wilde and Silka42,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) . This was particularly relevant for nutritious food like fruits, vegetables fish and meat that were more expensive(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84–Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) . Culturally specific foods were also considered more expensive(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Jacobus and Jalali57,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73–Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Addo, Brener and Asante80,Reference Cerin, Nathan and Choi81,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84,Reference Leu and Banwell85) , particularly in places where there was a low presence of these foods(Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84). Even though halal stores were considered trustworthy, they were too expensive to rely on for all food purchases(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78). For Muslim immigrants, the price of halal and non-halal foods influenced the type, quantity, quality and nutritional value of foods acquired(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78). In addition, fruits and vegetables (and ethnic foods in some cases), were more expensive in local food stores in walkable areas and cheaper in larger stores, further away, requiring transport(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Cerin, Nathan and Choi81) . The quality of food was a major concern, where fresh foods without chemicals were desired, ‘organic’ foods were unaffordable(Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74) , whereas processed foods including fast food were cheap(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Leu and Banwell85,Reference Lofink87) . The cost of food determined where they shopped(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32), what they purchased and the variety they consumed(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Carney and Krause55,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71) . Participants needed to buy the cheapest foods, so they found the sources with the lowest prices for the items they wanted, often good quality, fresh food(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Hammelman50) .

Socio-cultural environment

Forty-one articles out of sixty eight included articles had data pertaining to the socio-cultural environment.

Food values

Food values refer to immigrants’ desire for high quality, fresh, chemical-free and unprocessed foods, in particular fruits and vegetables, natural foods in their natural state(Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Park, Quinn and Florez41,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Leu and Banwell85,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) , perceived as good for health(Reference Park, Quinn and Florez41,Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75) . Fresh and homemade foods were important to immigrants(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65). They regarded host country foods with suspicion and equated these foods, particularly processed, preserved, canned or frozen foods as being old, filled with chemicals and therefore unhealthy and undesirable(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Yeh, Ickes and Lowenstein48,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Even the fruits and vegetables sold were viewed as having chemicals and hence there was a strong desire for organic foods(Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33). Fruits, vegetables and meat were experienced as having less taste and fragrance as compared with their home countries(Reference Bojorquez, Rosales and Angulo25,Reference Dawson-Hahn, Koceja and Stein31,Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Amos and Lordly70,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Addo, Brener and Asante80,Reference Leu and Banwell85,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) , and this was perceived as evidence of lower quality and nutritional value(Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Some did not trust tap water for consumption and relied on bottled water(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). Not knowing where foods came from led to a lack of trust.

(Cultural) food preferences

Overall, immigrants expressed a strong desire to eat their traditional foods(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) based on fresh foods they considered healthier(Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Amos and Lordly70,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Leu and Banwell85) , maintaining these eating habits was important to them(Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) . However, some thought that their cultural foods were ‘greasy’ and had too big portion sizes as well as consisting of lot of meat(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Preparing traditional foods reinforced the link to the home country and was a way to pass on traditions(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Jacobus and Jalali57,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) , whereas adopting host country foods made them feel more integrated(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65). Limited accessibility to preferred foods and the lack of flavour in host country foods forced them to find new ways of making traditional dishes(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Amos and Lordly70) with familiar produce(Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Fish, Brown and Quandt56,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) . To prevent dietary acculturation, some parents tried to control children’s food choices and mainly provided traditional foods at home(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75) . Immigrant families varied from eating primarily traditional food to eating a combination of both traditional and host country foods(Reference Sastre and Haldeman68,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . Parents, particularly fathers, preferred traditional food(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Some immigrants living in smaller metropolitan areas adapted to what was available and served their children processed foods due to limited access to healthier foods(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69). The convenience of host country foods was appreciated, though perceived as having potential negative health outcomes(Reference Amos and Lordly70). In the home country, meat and packaged foods were seen as luxuries(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64), while they were eaten more often after migration(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63). Immigrants would sometimes crave unhealthy foods, both host country and traditional forms(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65). For those with onset or presence of a health condition, it affected how they ate and therefore procurement to some extent(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69). Participants from Africa, Middle East and South East Asia, most of whom were Muslim, reported that religion was very important in determining their food choices(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Sastre and Haldeman68) .

Social support networks and changing roles

Immigrants’ reported relying on social networks from the same ethnic community generally and in relation to acquiring food(Reference Hammelman50). The family unit was at the core of the support circle and friends and neighbours were also included(Reference Hammelman37), though they experienced much less social support and connection than in their home countries(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Sussner, Lindsay and Greaney45,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Within the family resources were pooled and shared for food(Reference Hammelman37) and social networks mainly supported acquisition of affordable food through transport (rides in personal vehicles) and sometimes childcare(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Hammelman37,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) . There was also an exchange of money, services and food with friends and other community members(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). Ethnic enclaves facilitated cultural norms in the host country as well as enabled easier support through social networks(Reference Bowen, Casola and Coleman26).

Although men were more involved in household chores following migration, women found themselves responsible for practically all aspects of home life, with less time for food preparation(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78). Cooking was a responsibility that seemed allocated to women irrespective of their employment status for the majority(Reference Bojorquez, Rosales and Angulo25,Reference Sastre and Haldeman68) . If there was no woman in the household available to cook, ready meals and convenience foods were more likely to be relied upon(Reference Bojorquez, Rosales and Angulo25). Food went from being a social aspect of life to fulfilling more of a biological function(Reference Sussner, Lindsay and Greaney45).

Children’s influence

Children were more acculturated through exposure to outside food environments like school, neighbourhoods and peers as compared with their parents(Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Cerin, Nathan and Choi81,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) . They had a preference for and wanted parents to provide host country foods, often processed ones(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Parents wanted to provide what they knew as good and healthy food, which were often rejected by their children(Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Sussner, Lindsay and Greaney45,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) and some started cooking host country foods for the whole family, in spite of protests from their husbands(Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91). Prioritising family cohesion and positive relationships meant providing the desired foods(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Willis and Buck66) . There was a conflict between the food parents valued and what children desired(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Park, Quinn and Florez41,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) , wanting them to eat a sufficient amount(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30) and being happy(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) . Some parents looked for acceptable (halal) versions of fast foods(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63) and learnt how to make the host country foods that the children asked for(Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79) . In this way, children were agents structuring shopping and dietary intake(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63). Some parents who had experienced food shortages compensated by letting children indulge in foods of their choice(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69) . In a recent study on adolescents, 60 % reported that they influenced household food selection and 21·5 % reported having full control over what was eaten at home(Reference Sastre and Haldeman68).

Eating out

Pre-migration, eating out at restaurants was an occasional treat(Reference Phan and Stodolska43); however, after migration eating out became much more common, so much so that it became a regular event even for working class immigrants(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Amos and Lordly70,Reference Lofink87) . Some immigrants found themselves time poor and eating out or consuming convenience food was a way to have something to eat that was cheap and fast, replacing to a certain extent the burden of shopping and cooking foods at home(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . Fast food restaurants were experienced as cheap and child friendly, facilitating eating out as families(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38), though it took away the control over healthier choices(Reference Zou77). Families ate out more due to children’s desire for fast foods(Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91) .

Political environment

Twenty four out of sixty-eight included articles had content pertaining to the political environment. Primarily, government support and food assistance programmes were mentioned. The use of such benefits and assistance was related to need, awareness, cultural norms, past experiences and language barriers(Reference Willis and Buck66).

Government food related benefits

Government food-related benefits, such as Women, Infants and Children, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and free and reduced school meals in the USA and the Australian Centrelink were all mentioned in the studies and enabled families to have enough food till the end of the month. Food benefits were highly depended on(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). This was particularly appreciated in times of need(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58) and was seen as a facilitator to food security(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Sano, Garasky and Greder67,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) . Though these benefits were supplementary in nature, many families reported them as the main family food budget(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Hammelman37,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62) , although insufficient(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63) . However, not all immigrants accessed all benefits(Reference Sano, Garasky and Greder67). The knowledge, time and resources needed to apply for state food benefits, particularly relating to automated and literacy demanding application processes, prevented some immigrants from applying(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) or reapplying once they lapsed(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) . Undocumented migrants or others with concerns about their immigration status may also be deterred from accessing these schemes(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39) .

These safety net programmes helped immigrants access healthy food and improved access to culturally acceptable, staple foods(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33,Reference Hammelman37–Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58) . Benefits were typically spent within 1–2 weeks of issuance(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49) . Immigrants then resorted to cheaper food including host country foods(Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53).

Food assistance

Immigrants mentioned having used emergency food assistance (food pantries, food banks) in the past, particularly in their first 2 years in the host country(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74) and from being very reliant to not using it at all(Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) . Faith-based organisations providing food assistance were perceived as safe regarding immigration status since they did not require identification(Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Vahabi and Damba76) . Barriers to usage included stigma, issues of access(Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Vahabi and Damba76) as well as food being of poor quality or culturally inappropriate, like canned food(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . For Muslims, food assistance was often inappropriate since they did not provide halal foods, resulting in wastage(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78). Food pantries provided standard sized packs of short term emergency food relief(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29) and relied on donated items, often with a long shelf life(Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73) . There was very little fresh food and what was available was often old or rationed out quickly(Reference Vahabi and Damba76).

Overarching themes: interconnectedness between aspects of the food environment

In addition to the four distinct themes based on the ANGELO framework, we identified three themes that characterised the interconnectedness between different aspects of the food environment interactions and immigrant populations: time scarcity (sxiteen articles), mobility (twenty-six articles) and navigating the food environment (forty-four articles).

Time scarcity

Available time, primarily linked to gender based double work burden, played an important role in determining the extent to which immigrants could pursue food provisioning activities and therefore in which way they interacted with the food environment. This theme was a combination of the socio-cultural, economic and physical environments. Life following migration was described as hectic and time was scarce due to women being engaged in paid work, studies or other commitments, while continuing to be responsible for caring and preparing food for the family(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39) . For those in paid work, time scarcity was a major issue; there were often long hours(Reference Addo, Brener and Asante80), multiple jobs and long distances to travel to work, including sometimes working at night to care for children during the day(Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29). For some this meant ending work late when most food stores were closed, apart from corner stores that sold limited healthy options(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Chaufan, Davis and Constantino29) . These structural changes within the family shifted the eating patterns of the whole family(Reference Sussner, Lindsay and Greaney45,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71) . Lack of time as well as childcare responsibilities minimised time for shopping, making it more challenging to prioritise healthy foods and cooking from scratch(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Addo, Brener and Asante80) . Not having enough time meant that food provisioning needed to be easy, fast, convenient and close by(Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91). This sometimes led to time-saving shortcuts, including turning to and becoming reliant on convenience foods, leftovers, snacks, skipping meals or eating on the go, something they were aware was not conducive to their health(Reference Sussner, Lindsay and Greaney45,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Blanchet, Nana and Sanou71,Reference Zou77,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Cheap processed foods were used during time scarcity since traditional foods took longer to make(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . However, foreign-born women were more likely to view food provisioning as an essential task as opposed to weighing in the effort required when buying and preparing food(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32).

Mobility

Being flexible about where to buy foods allowed access to more affordable foods that aligned with their values and preferences and therefore determined how immigrants interacted with their food environment. Money and time constraints were compounded by lack of transport(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63). This theme could be seen as an interplay of the physical, socio-cultural and economic environments, as well as the previous theme, time scarcity. Being mobile was a way of trying to reduce food insecurity(Reference Hammelman50). Access to transport and time therefore facilitated this process by allowing for the acquisition of healthier affordable foods, by being able to travel further and to travel to multiple stores that offered the food they wanted, at prices they could afford(Reference Chaufan, Constantino and Davis28,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Cerin, Nathan and Choi81,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . Proximity of food shops to home was one factor in determining access(Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86). Owning a car or relying on family and social networks within the larger ethnic group to acquire rides were key(Reference Sharkey, Dean and Johnson44,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) . Public transport routes and timings were limited for those who lived further away from the center(Reference Jacobus and Jalali57), costing money and time, with inconvenient connections between neighbourhoods and food stores(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . Walking or relying on public transport meant carrying multiple heavy bags and quantities purchased were limited to what they could carry themselves(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) . Additionally, being accompanied by children and walking distances(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) ; this meant visiting fewer stores and some food sources were not accessible at all(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82) . Weather conditions and cold season were an added challenge when relying on public transport(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Some women were dependent on others since they did not know their address, and others could not travel by taxi due to religious restrictions for women(Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79). Some could not afford cars, while others acquired personal vehicles as soon as they were able to, in order to facilitate food procurement(Reference Jacobus and Jalali57,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . The high financial costs of car expenses(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) meant weighing whether it was worth travelling further for the amount saved in cheaper food(Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86). Cycling was mentioned by international students who pushed their cycles home loaded with groceries(Reference Leu and Banwell85). Those who relied on ethnic stores for most purchases travelled further to more affordable stores(Reference Yi, Russo and Liu60,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Immigrants were willing to travel through the city or beyond for food that was suitable in relation to cost, quality, what was valued and cultural preferences(Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Franzen and Smith51,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Cerin, Nathan and Choi81,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84,Reference Leu and Banwell85,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell88) .

Navigation

This theme combined aspects of the economic environment, socio-cultural and physical environment with themes of time scarcity and mobility. Immigrants often faced a new language and a new food system(Reference Grauel and Chambers35) and relied on members of their community to initially guide them in the new food environment(Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) including shops, products and new ways of eating(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2). Neighbours from the same religion showed them how to identify and where to get hold of appropriate foods(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . Social media groups shared how to access and determine culturally appropriate and affordable foods, including halal foods and current deals(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) . Without this, difficulties accessing foods and stores were harder to overcome(Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63) . Yet, navigation improved with time; it took the first few years to confidently shop for foods(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Rodriguez, Dean and Kirkpatrick75,Reference Vahabi and Damba76) . Pre-migration food procurement skills included acquiring quality raw, fresh foods from markets, stores or home gardens(Reference Grauel and Chambers35,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Gichunge, Somerset and Harris82,Reference Wilson, Renzaho and McCabe83) and now foods were in unfamiliar packaging and methods of storage, such as frozen foods(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74) . Those with little prior experience of food provisioning before migration or were cooking for themselves acquired more easy convenient food(Reference Willis and Buck66).

Lack of language skills and literacy were barriers to food security(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62,Reference Sano, Garasky and Greder67,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) , navigating public transport(Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) , identifying stores, food items and deals on food(Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo36,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Vahabi and Damba76) or being able to read and understand food labels(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Judelsohn, Orom and Kim58,Reference Paré, Body and Gilstorf61,Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Henderson, Epp-Koop and Slater73,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) . For some, language barriers persisted over time, particularly for older immigrant women(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret62), making it harder to be independent in procuring food(Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79). For Muslim immigrants, there was a fear of not adhering to halal standards, which meant restricted options(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2,Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78) . This meant that some had to shop with their husbands or children(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) , and therefore children had to tag along, indirectly leading to more processed foods and sweet items being bought(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty69,Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79) . Some believed that if food was for sale in stores, it must be healthy(Reference Mannion, Raffin-Bouchal and Henshaw79). For some, there was a lack of trust even towards ‘halal’ foods as there had been cases of foods deliberately mislabelled as halal(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen2). In other groups, women were better at navigating the food environment than men(Reference Willis and Buck66,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84) and those who migrated from urban environments found it easier to adapt to the new food environment than those from rural areas (Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold74). Physical access (location and transport) was a deciding factor in where participants purchased their food, facilitated by social networks(Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49). Self-efficacy also a played a role in perceived ease of access to fruits and vegetables(Reference Gase, Glenn and Kuo34).

Immigrants implemented a range of strategies in order to feed their families, which spanned across all the themes. Overall, they aimed for the best quality at the lowest price at the most convenient location(Reference O’Mara, Waterlander and Nicolaou91). Which strategies were used depended on a variety of factors such as access to time and money, availability of cheap food and transport(Reference Hammelman37), a working knowledge of the local language(Reference Burge and Dharod27) and social networks. There was a cyclical pattern of having enough at the beginning of the month and having a shortage at the end of the month, when staples were relied on(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). The use of coping strategies that included a variety of activities to take advantage of deals(Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld32,Reference Hammelman37,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Phan and Stodolska43,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Carney and Krause55,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84) , aimed at getting cheaper but healthier food(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54,Reference Carney and Krause55,Reference Yeoh, Lê and McManamey84) , was associated with being more food secure(Reference Sano, Garasky and Greder67). Shopping for fruits and vegetables meant being flexible and taking advantage of deals and seasonal foods(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney38,Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47,Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54) . Time-poor immigrants particularly relied on stretching their budget(Reference Carney and Krause55) by buying inexpensive staple foods in bulk to last the month(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Hammelman37,Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64,Reference Vahabi and Damba76,Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86) , non-perishable items to stock up on(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33) and cooking cheap traditional meals(Reference Kiptinness and Dharod49,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) . Due to financial constraints, participants reported compromising on the variety(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Hammelman50,Reference Nunnery and Dharod64) and quality of food in order to have a sufficient amount to eat(Reference Munger, Lloyd and Speirs40,Reference Cordeiro, Sibeko and Nelson-Peterman53) . More expensive food items were adjusted by decreasing the amount bought(Reference Yeoh, Lê and Terry86). Foods were prioritised in different ways, such as foods higher in protein and foods that do not spoil easily or are the most filling(Reference Hammelman50). Limiting the purchase of more expensive foods, supplementing with homegrown food(Reference Burge and Dharod27,Reference Hammelman37) and eating at home also helped to lower spending(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm30,Reference Fuster and Colón-Ramos33) . Social networks sometimes functioned as a place for food sharing as well as buying prepared foods from neighbours or friends(Reference Hammelman37,Reference Meierotto and Som Castellano39,Reference Sharkey, Dean and Johnson44,Reference Hammelman50) . They turned to frozen, canned and prepared foods to deal with economic access(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78,Reference Leu and Banwell85) . When money was finished, food was sometimes bought on credit at ethnic stores(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). Skipping meals, eating cheap processed foods and as well as kids taking advantage of food at school were coping strategies(Reference Nunnery and Dharod64). Cheap fast food allowed families to eat while on a budget(Reference Tiedje, Wieland and Meiers65). To afford fruits and vegetables, they frequented market stalls or Pulgas(Reference Valdez, Ramírez and Estrada52), as well as buying foods on sale(Reference Hammelman50) or buying seasonal foods(Reference Villegas, Coba-Rodriguez and Wiley47). When the budget was tight, quantity was prioritised over quality(Reference Bojorquez, Rosales and Angulo25,Reference Vasquez-Huot and Dudley46,Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90) . Fresh produce was weighed against more satiating higher energy foods such as fast food and meat when making decisions based on a limited budget(Reference Evans, Banks and Jennings54). Fresh items were purchased and consumed more towards the first half of the month(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63). Some reported reducing vegetables and meat and relying more on cheap culturally appropriate food(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag78). Some ethnic groups seemed to manage on what they had, whereas others struggled to have enough at the end of the month(Reference Patil, McGown and Nahayo63). Overall, the process was time intensive and required complex decision making and prioritising in order to make the whole effort worthwhile(Reference Hammelman37).

Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified sixty-eight studies addressing immigrants and the food environment published between 2007 and 2021. There was a paucity of research from countries other than the USA and a strong focus on women. Our major findings focus on the interactions between immigrant consumers with different aspects of the food environment and their interconnectedness: (1) Fresh high-quality natural foods and cultural foods were strongly valued, though children were more exposed to and demanded host country (often nutrient poor) foods; (2) Navigating the new food environment on a low income resulted in coping strategies where additional food skills were needed and (3) Time and mobility were key to determining potential trajectories of accessing healthier or less healthy foods.

Immigrants valued fresh, chemical-free, unprocessed healthy foods and had a set of skills and strategies to buy and prepare these, in spite of living on low incomes and facing other barriers. These values seem to be an internal motivator compelling them to surpass barriers and acquire healthier foods, stemming from a cultural or traditional discourse where simple and natural foods is deep rooted(Reference Ristovski-Slijepcevic, Chapman and Beagan92). Several studies have found that immigrants or less acculturated groups in high-income countries are able to acquire a healthier diet at a lower cost than the host population(Reference Mackenbach, Dijkstra and Beulens93–Reference Aggarwal, Rehm and Monsivais95), a phenomenon termed as ‘nutrition resilience’(Reference Aggarwal, Rehm and Monsivais95). In our study, this was shown in the industrious way they strived to access food they valued. This relates to findings demonstrating that availability in the environment and outcome behaviour are often not directly linked, but rather that the interaction is moderated by personal factors(Reference Travert, Sidney Annerstedt and Daivadanam96). A systematic mapping review on factors influencing dietary behaviour in immigrants and ethnic minorities living in Europe had similar findings as our review, but focused more on the individual level(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell97). Food advertising, another known influencer of food choices(Reference Boyland and Halford98), was not mentioned in our studies. It is, however, likely that parents were indirectly influenced by their children’s exposure to advertisements.

Our review characterised immigrants as struggling financially. Due to the high reported costs of cultural and fresh healthy foods, they had to compromise on the quality of food in order to have enough. This was confirmed in a study that reported high costs leading to prioritising quantity over quality, therefore limiting access to fresh foods such as fruits, vegetables, fish and meat(Reference Kamimura, Jess and Trinh99). Navigating their new food environment required food literacy in addition to the food skills that they had in order to enable healthier choices when buying packaged foods(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos100). An Australian study suggested that food literacy would not remove the wider environmental and economic causes of food insecurity but could decrease vulnerability to the obesogenic environment(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos100). Navigating this was easier if they were able to access a social network (community of the same ethnicity) that could partially bypass other barriers such as showing them where to shop or what to buy(Reference Amstutz, Gonçalves and Hudelson90), thus making them less vulnerable. In our study, all packaged, processed and preserved foods were grouped into foods that were not fresh and therefore less healthy. A study on perceptions of processed foods among low-income and immigrant parents confirmed these findings – where packaged food including frozen and canned foods were considered processed irrespective of the contents(Reference Bleiweiss-Sande, Goldberg and Evans101). This is not just an issue of knowing how to read food labels, but rather a food value that may be a hindrance to eating well in host countries, since frozen healthy foods including vegetables may be more affordable with practically the same nutritional value as the fresh versions. Also these parents bought processed foods because their children liked them, but they did not think that these foods were as healthy as fresh, homemade foods were(Reference Bleiweiss-Sande, Goldberg and Evans101), indicating that solely nutrition education may not be the most appropriate approach in order to improve immigrants’ diet.

When there was a lack of income, time and mobility were buffers to food insecurity by allowing access to affordable valued foods, as confirmed in another study(Reference Clifton102). In our review, lack of time stemmed primarily from women’s double work burden, confirmed by another study that showed immigrants, had a higher chance of being severely poor in both time and income(Reference Merz and Rathjen103), and those who were employed had younger children or were single parents were more likely to be time poor(Reference Clifton102), as we found. Time scarcity seems to have an immediate effect on food choices – linked to eating out and excess energy intake, as well as a decrease in fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Venn and Strazdins104). A study on low-income women found that nutritional value became less prioritised when food needed to be put on the table quickly; however, higher levels of confidence in food preparation and cooking skills enabled them to prioritize and make more time for cooking(Reference Jabs, Devine and Bisogni105). Though the immigrants in our review were vulnerable in their new circumstances, they also had strong food provisioning skills and reported striving to access fresh, healthy food. A study on non-immigrants showed how food decisions were made weighing in time and monetary costs, as well as quality and health benefits of foods against time and effort(Reference Webber, Sobal and Dollahite106). In our review, culturally valued foods, quality of foods and monetary costs seemed to weigh more than time and effort, linked to how food provisioning may be considered an essential task.

With respect to mobility, another study confirmed our findings showing that acquiring rides was found to be convenient for purchasing larger quantities at stores that were less accessible by foot, procuring higher quality foods that aligned with their values and preferences, and at the same time, avoiding the costs of car ownership(Reference Clifton102). A study from Australia found that having access to independent transport was the key to accessing foods, rather than whether they lived in a food desert or not; this confirmed our findings on how reliance on public transport poses difficulties for food shopping(Reference Coveney and O’Dwyer107). Being mobile meant that they did not have to be confined to accessing foods solely in local stores, which were considered to be more expensive as well as perceived to have foods of lower quality.

Low- and middle-income countries are also experiencing changes to their food environments and diets due to globalisation(Reference Baker, Machado and Santos108), which means that some changes towards a Western diet may already take place in the home country, before migration. Within country migration from rural to urban areas has also been found to cause similar changes including consumption of cheaper types, more sugar and dairy products and more meals outside of the home due to the low incomes, high food costs and lack of time in their hectic city life(Reference Opare-Obisaw, Fianu and Awadzi109). Dietary acculturation is a dynamic, multi-dimensional and complex process(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser110) that progresses over time. Even though in our study we see immigrants striving to maintain their food culture in different ways, it represents only a part of a broader process(Reference Satia-Abouta111). Studies have shown that over time immigrants incorporate their host food cultures across a spectrum from subtle and explicit ways(Reference Elshahat and Moffat112). Our study also shows that the process of dietary acculturation is not so much an active choice solely due to changes in preferences after exposure to a new food culture, but rather due to an array of factors often out of their control, that interplay to push food decisions closer to that of their host country.

We found that a majority of the studies mentioned insufficient incomes in the different immigrant groups and the implications of this on different aspects of life, including food procurement. In order to access valued and preferred foods, immigrants reported travelling to stores to mitigate food insecurity. However, this implied a decrease in the budget by having to spend on public transport or fuel. Increased time spent travelling could potentially lead to less time for preparing and cooking, which may result in more reliance on convenience foods. Financial constraints paired with problems navigating the food environment, particularly in the early period following migration, may act as a catalyst of change that can be difficult to reverse, even though the aggravating factors may improve over time. This review also highlighted how unhealthy food exposure, primarily through schools and peers, has a ripple effect on family procurement and consumption patterns through changes in children’s food preferences, serving as a possible catalyst for dietary acculturation. The complex interactions inherent in this process could result in food insecurity and a diet that is less healthy, increasing the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and CVD(Reference Holmboe-Ottesen and Wandel113). The disproportionately high rates of non-communicable diseases including obesity among immigrants, both adults and children, is also a reflection of the cumulative effects of such changes over time(Reference Smith and Coleman-Jensen114).

Strengths and limitations

We sought to characterise interactions with the food environment in a diverse group of immigrants through studies of different designs and focus. Most studies were about Latino immigrants in the USA, hence, affecting the transferability of the findings. Moreover, the experiences of men were lacking in the literature, creating a women bias. Through the search strategy, some relevant articles may have been missed, though we covered 14 years of published research in the field. Our decision to perform an additional qualitative analysis of extracted data was based on the recommendation by Levac et al., 2010(Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien19), though we chose to stay closer to the data through the ‘Best fit’ framework synthesis and prevented a ‘pressing in’ of the data by allowing ‘left over’ data to be analysed outside of the framework. The ANGELO framework was used as it explicitly links health aspects to the food environment.

Conclusion

This study brought together evidence from a range of studies on interactions between immigrant populations and the food environment, using the four a priori themes from the ANGELO framework including the physical, economic, socio-cultural and political environments. Additionally, we identified the overarching themes of time scarcity, mobility and navigation that illustrated these interactions and interconnected the different aspects of the food environment. Immigrants tried to access fresh, traditional, healthier food and were compelled to do so, though they faced structural and family-level barriers that affected the healthiness of acquired food. Our study points towards the need for further research on different types of immigrant groups, including asylum seekers and refugees; families v. single individuals; the perspective of men; other parts of the world other than the USA that have experienced big waves of migration and the interaction of values with objective measures of the food environment. More importantly, research needs to focus on the most vulnerable and how they can be protected and supported through this process. Understanding the food environment and interactions therein is key to proposing interventions and policies that can potentially impact the most vulnerable.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Our sincere thanks to the Uppsala University Library for support with developing the search strategy for this scoping review. Financial support: This work was supported by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 funding for Health Coordination Activities under the call ‘HCO-05-2014: Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases: Prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes (M.D., Project SMART2D, Grant Agreement No 643692); and the Crown Princess Margareta’s Memorial Foundation, Sweden (A.B-C.) The funders have not been involved in the development or process of carrying out the scoping review. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Conceptualisation: A.B.C., S.H.P., M.D.; data curation: A.B.C., S.H.P.; formal analysis: A.B.C., S.H.P.; funding acquisition: M.D., H.M.A.; investigation: S.H.P., A.B.C.; methodology: M.D., A.B.C., S.H.P.; project administration: M.D., A.B.C., S.H.P.; supervision: M.D., A.A., H.M.A.; validation: S.H.P., A.B.C.; visualisation: S.H.P., A.B.C.; writing – original draft: A.B.C., S.H.P.; writing – review and editing: M.D., A.A., H.M.A. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021003943