Impact statement

With the globalization of the mental health field, psychology programs are lagging behind addressing in their curricula global events impacting the mental health of people and societies worldwide. This results in inadequacy in preparing professionals to meet the diverse challenges of society today. This article highlights the inclusion of global mental health in the training and education of psychology. Future psychologists should be trained on subjects including human rights and social justice, advocacy, health management, policymaking and leadership. These topics are treated as important knowledge and competencies to acquire for the 21st century psychologist. By developing these skills, future psychologists may apply their expertise to advance the global mental health field improving services (access and equity) to benefit communities located in various parts of the globe.

Introduction

The historical events occurring in the 21st century such as natural disasters (earthquakes, hurricanes and tsunamis), man-made disasters (wars, conflicts and terrorist attacks) and epidemic and pandemic outbreaks (COVID-19, Ebola, H1N1) confirm the need to equip psychologists and general healthcare workers to provide evidence-based, culturally relevant and contextually appropriate mental health interventions focused on human rights and social justice frameworks across the world (WHO, 2019; 2022; Bahar et al., Reference Bahar, Cavazos-Rehg, Ssewamala, Abente, Peer, Nabunya, de Laurido, Betancourt, Bhana and Edmond2021).

Integrating global mental healthcare into undergraduate and graduate academic programs is crucial. Specifically in areas that require mental health professionals to work with under-represented minorities and at risk groups from various backgrounds – migrants, neglected populations, individuals enduring extreme trauma, survivors of man-made, natural disasters, and human rights violations as well as living under the poverty line and low, middle-resource communities (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Tol, Jordans, Sabir, Amin, Bolton, Bass, Bonilla-Escobar and Thornicroft2014; WHO, 2019; 2022; Meffert, Reference Meffert2021). The inclusion of global mental health (GMH) disciplines and/or programs into the academic curricula would also aid in developing psychologists and healthcare professionals’ skills. Among these skills, advocate for social inclusion, propose and implement policies working in collaboration with governments and organizations, coordinate capacity building initiatives, adhere to international ethical principles in the field of psychology and facilitate the development of sustainable holistic treatments taking into account important contextual determinants (e.g., historical events, economics, politics, environment, globalization and technology) to promote health and mental health (IUPsyS, 2008; Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010; de Castro and McGrath, Reference De Castro, McGrath and Uslu2015; Kuruvilla et al., Reference Kuruvilla, Sadana, Montesinos, Beard, Vasdeki, de Carvalho, Thomas, Brunne Drisse, Daelmans, Goodman, Koller, Officer, Vogel, Valentine, Wootton, Banerjee, Magar, Neira, Marie Okwo Bele, Marie Worning and Bustreo2018; Weir, Reference Weir2020).

Global mental health

In addition to the historical events mentioned above, the global threats to mental health indicated in the World Health Organization’s (WHO, 2022) report are, “economic downturns and social polarization; public health emergencies; widespread humanitarian emergencies and forced displacement; and the growing climate crisis” (p. 26). There are three bases of evidence supporting the inclusion of GMH in the curricula of healthcare-related disciplines (Rajabzadeh et al., Reference Rajabzadeh, Burn, Sajun, Suzuki, Bird and Priebe2021) and particularly in psychology (de Castro and McGrath, Reference De Castro, McGrath and Uslu2015). First, the significant number of cross-cultural and transnational research discussing inequities in the provision of mental health care and the barriers to access mental health services in high-, middle- and low-income countries (Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Minas, Cohen and Prince2014). Second, the exponential increase in epidemiological research confirming the burden of mental disorders in all world regions prior and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Rehm and Shield, Reference Rehm and Shield2019; Nochaiwong et al., Reference Nochaiwong, Ruengvorn, Thavorn, Hutton, Awiphan, Phosuya, Ruanta, Wongpakaran and Wong Pacaran2021). In fact, according to the WHO (2019), “people with mental disorders experience disproportionately higher rates of disability and mortality” (p. 2). Third, the evidence that there are effective pharmacological and psychological interventions available for the treatment of mental health disorders, and that general healthcare workers can prescribe the medications and deliver the services (Patel and Thornicroft, Reference Patel and Thornicroft2009).

The advancements of the GMH field can be traced back to 2007 when the Lancet Medical Journal published a series of articles focusing on the topic (Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010). In the mentioned series, an action plan was drafted with the goal of scaling up services based on human rights approaches and empirical studies to treat individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders. In the decades that followed Lancet’s call for action, the field of GMH gained prominent visibility prompting the interest of psychologists and healthcare professionals in diverse parts of the world. GMH became an area of study and research supporting practices concerned with inclusion, equity, human rights, and social justice and responsibility (Koplan et al., Reference Koplan, Bond, Merson, Reddy, Rodriguez, Sewankambo and Wasserheit2009; Civitelli et al., Reference Civitelli, Tarsitani, Rinaldi and Marceca2020; Meffert, Reference Meffert2021).

GMH education

The WHO along with a commission of organizations and individuals devoted to enhancing the mental health care across nations launched the Mental Health Global Action Program (mhGAP) and the Movement for Global Mental Health. The WHO has acknowledged the mhGAP to be its “flagship” (p. 2) program in mental health. The program provides evidence-based guidelines for the general healthcare professionals to treat specific mental and neurological disorders in multiple settings (Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010). The conditions prioritized in the mhGAP program and assessed through the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Eleventh revision (ICD-11; WHO, 2019) are depression, psychoses, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, alcohol and substance disorders, suicidal ideation, anxiety disorders, epilepsy, dementia, intellectual disabilities, as well as mental and behavioral disorders observed during childhood and adolescence, and due to the exposure to acute stress. While the WHO was proposing the mhGAP program, a coalition of institutions and individuals was established to develop The Movement for Global Mental Health program. The Movement for Global Mental Health program was inspired by the success of the HIV Treatment Action Campaign – their mission was to expand the access to psychopharmacological and mental health treatment in various parts of the world.

Heeding the worldwide call to move toward a more inclusive and effective service model guiding GMH practices, and using the examples set by Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières) and Partners in Health (Hixon et al., Reference Hixon, Yamada, Farmer and Maskarinec2013), various schools in the healthcare field (e.g., medicine, psychology, social work, nursing and public health) decided to develop disciplines and graduate programs in the area. The academic interest in GMH has been on the rise especially in the USA and other developed nations. The Centre for Global Mental Health in London focusing on capacity building initiatives in GMH, the Master’s in International Mental Health Policy, Services and Research offered by the University of Lisbon, the Grand Challenge in Global Mental Health led by the National Institute for Mental Health and the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010), the Global Mental Health Programs at McGill University, the Columbia University Global Mental Health programs, Johns Hopkins Global Mental Health program housed within the School of Public Health, School of Medicine Yale Global Mental Health program and the Master’s in Arts and the Doctorate programs in International Psychology offered by The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, training psychologists and other healthcare professionals to design and evaluate interventions in the GMH field based on human rights and social justice frameworks are illustrated (de Castro and McGrath, Reference De Castro, McGrath and Uslu2015).

The Caracas Declaration signed in 1990 was one of the most important hallmarks to advance mental health services in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). With the support of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), LAC was tasked to build a collaborative and interprofessional model of assistance integrating mental health into the community and the primary healthcare system (Mascayano et al., Reference Mascayano, Alvarado, Martínez-Viciana, Irarázaval, Durand-Arias, Montenegro, Bruni and Bruni2021). Based on a research coordinated by PAHO (2017), the prevalence of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in the Americas ranged from 19% to 24%, and 4% in Latin America. However, it is important to note that the report focused on 12-month mental health illness prevalence studies from “the most representative community-based survey of a country” (Kohn et al., Reference Kohn, Ali Ahsan, Puac-Polanco, Figueroa, López-Soto, Morgan, Saldivia and Vicente2018, p. 2). In addition, studies reporting the prevalence of mental health disorders in Latin American countries are scarce and they vary considerably depending on the design and methodology used. Therefore, the data presented in the PAHO (2017) report may not reflect the reality of mental health disorders in Latin America. The numbers may be even higher. Despite these obstacles, the mental health services provided in LAC significantly improved in the past 20 years incorporating mental health in primary care and enhancing the access of mental health care in the community (Caldas de Almeida, Reference Caldas de Almeida2013; Sapag et al., Reference Sapag, Álvarez Huenchulaf, Campos, Corona, Pereira, Véliz, Soto-Brandt, Irarrazaval, Gómez and Abaakouk2021). In Brazil, the Federal University of São Paulo (Department of Psychiatry) offers opportunities, at the master and doctorate levels, to conduct research studies in the field of GMH (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Sharan, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera, Seedat, Mari, Sreenivas and Saxena2007; Sharan et al., Reference Sharan, Gallo, Gureje, Lamberte, Mari and Mazzotti2009; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Semrau, Alem, Drake, Ito, Mari, McGeorge, Tara and Semrau2011; Oquendo et al., Reference Oquendo, Duarte, Gouveia, Mari, Mello, Audet, Pinsky, Vermund, Mocumbi and Wainberg2018; Marques et al., Reference Marques, Minelli, Ferigato and Marcolino2022). Nonetheless, formal training and graduate programs in GMH, encouraging culturally and contextually oriented knowledge, competencies, skills and practices, are yet to be developed in South America (Rich et al., Reference Rich, Padilla-Lopez, De Souza, Zinkiewicz, Taylor-Jackson and Jaafar2018; Rich et al., Reference Rich, Padilla-Lopez, Ebersohn, Taylor-Jackson and Morrisey2020).

Competencies in the GMH field

Around the world, the discipline of psychology is discussed, studied, adapted and practiced within a multitude of contexts based on diverse social, education, political, economic and legal norms. The changes that are being made in the profession itself to address the never-ending challenges of global societies (mental health illness) reflect the development of academic programs, disciplines and training to equip the professionals with international core and specific competencies to conduct ethical work that is inclusive and based on cultural/contextual practices (de Castro and McGrath, Reference De Castro, McGrath and Uslu2015; Morgan-Consoli et al., Reference Morgan-Consoli, Inman, Bullock and Nolan2018; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Benedict, de Castro and Keith2018).

Countries differ vastly on the models of education and training of psychologists (i.e., number of years, theoretical frameworks, foundational literature, concepts, pedagogy, format of delivery, competencies, learning outcomes and internship requirement). Considering the broad scope, in 2013 a task force committee was assembled to identify universal benchmark competencies in the field of professional psychology during the 5th International Congress on Licensure, Certification and Credentialing. The conference held in Sweden, Stockholm was by invitation-only and included 75 participants from 18 countries (e.g., Norway, United Kingdom, Romania, South Africa, China, New Zealand, Colombia, Canada and USA to name a few) representing five continents. The event counted with the presence of important and prestigious global associations in the field of psychology – the International Association of Applied Psychology, the International Test Commission and the International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS) to support the development of a collaborative project with the goal to produce a document proposing an international competence model. Participants had access to relevant sources and material presenting the current available models on competence for psychologists prior to the first meeting and ran as an extended sequence of workshops consisting of lengthy small group discussions. Planners and participants also agreed to broaden discussions beyond local, regional and national differences to generate a mutual understanding of psychological competencies. At the end of the event, the task force committee proposed an agreement to establish a multi-stakeholder international project – The International Project on Competence in Psychology (International Association of Applied Psychology and International Union of Psychological Science, 2016).

To serve as the basis for a global professional identity in the field of professional psychology, and potentially be recognized as a universal system to assist with program accreditation, professional credentialing and regulation of professional competence and conduct, the International Declaration of Core Competencies in Professional Psychology (IDCCPP) is currently known as a foundational document guiding the work of psychologists worldwide. IDCCPP includes a preamble with working definitions of commonly used terms to have a comprehensive list of the language used within the declaration. It then lists the competencies that may be both explicitly applied worldwide (ethical practices) and less explicit but equally important (cultural humility). Following the definitions, the document presents the clusters of competencies based on psychological knowledge and skills underpinning the core competencies as well as competencies relating to professional behaviors and activities (Von Treuer and Reynolds, Reference Von Treuer and Reynolds2017). The competencies proposed are not specific but rather general, encouraging organizations, communities and regions to accommodate their local contexts as needed. Further, IDCCPP acknowledges that adaptations and translations may lead to variations in educational and training requirements across cultures and believe this will capture the variety of richness and expression in the international professional psychology field.

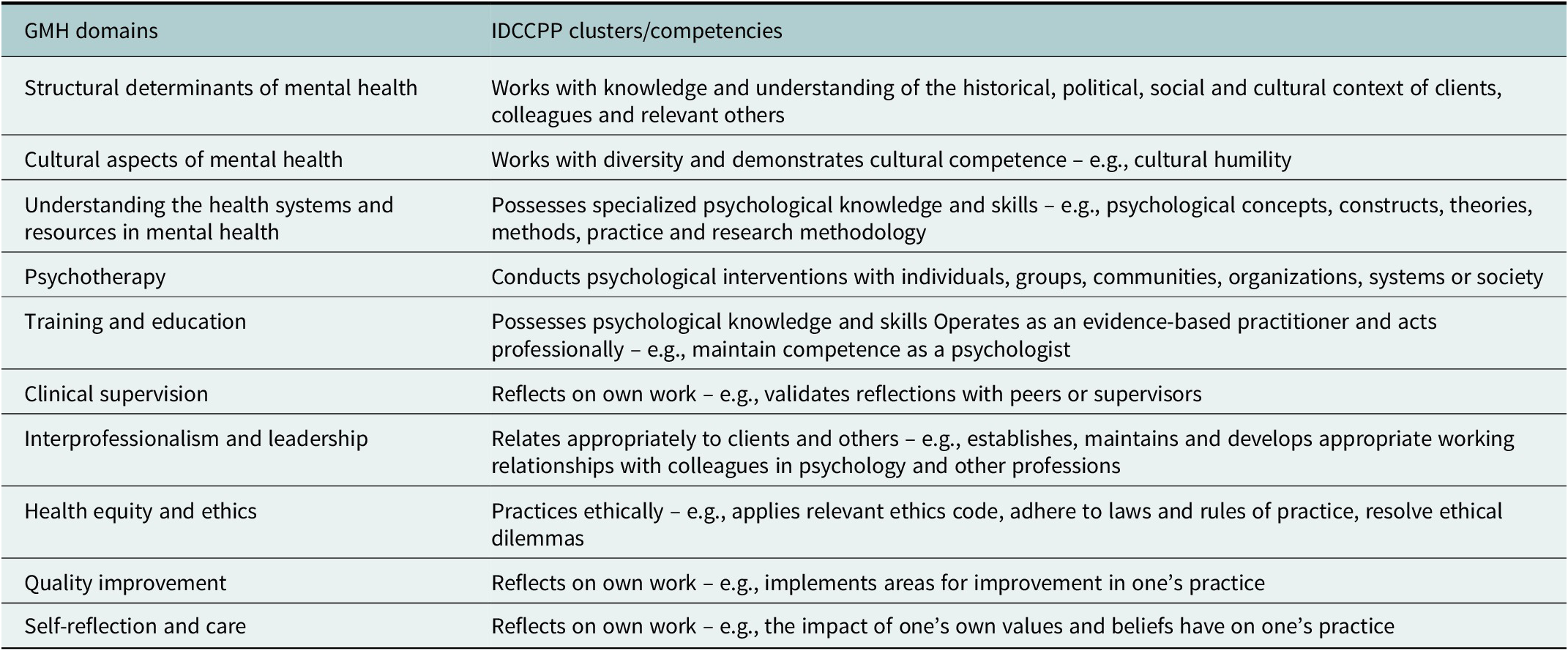

Recognizing the importance of training professionals working in the healthcare field, Buzza et al. (Reference Buzza, Fiskin, Campbell, Guo, Izenberg, Kamholz, Hung and Acharya2018) conducted a research to identify relevant GMH domains and competencies required to provide effective services in diverse parts of the world. Interestingly, several domains introduced in the study are closely aligned with the IDCCPP clusters and competencies (Table 1). Culturally informed and contextually driven psychologists, and healthcare workers in GMH, play significant roles contributing to enhance social inclusiveness, advocate for practices focused on social justice and advance policies protecting human rights. Yet, balancing competing needs (e.g., competence vs. cultural and social practices) remains a challenge to expand the training in GMH (Khoury et al., Reference Khoury, de Castro Pecanha, McGrath and Nolan2022). As the mental health crisis continues worldwide, the field of GMH will need to increase the number of competent professionals meeting the requirements to work in the mental health area and ready to deliver mental health services in international contexts (Weir, Reference Weir2020; Sapag et al., Reference Sapag, Álvarez Huenchulaf, Campos, Corona, Pereira, Véliz, Soto-Brandt, Irarrazaval, Gómez and Abaakouk2021; WHO, 2022). Psychologists will need to reinvent themselves stepping outside of the comfort zone of their own cultural frameworks and practices to ultimately develop a flexible, humble and adaptative global identity in order to provide effective services.

Table 1. Examples excerpt from global mental health (GMH) competencies for fellowship training and International Declaration of Core Competencies in Professional Psychology (IDCCP)

Humans rights, social justice and advocacy

Psychologists and general healthcare workers in the GMH field may encounter situations involving unethical, unfair, bias and discriminatory practices (Asanbe et al., Reference Asanbe, Gaba and Yang2018; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and UnÜtzer2018; Millum et al., Reference Millum, Campbell, Luna, Malekzadeh and Karim2019). In order to offer transformative mental health services, professionals should engage in critical self-reflection (e.g., one’s own impact on others), nurture deep respect for cultures (e.g., cultural humility) and demonstrate a strong ethical commitment, following the ethical principles included in the Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles for Psychologists, implemented by IUPsyS, in 2008, as an ethical framework guiding the work of psychologists in international contexts (Gauthier et al., Reference Gauthier, Pettifor and Ferrero2010).

Studies have shown that worldwide, many individuals with mental illness are isolated from society, and they are institutionalized for long periods of time with inhuman living conditions (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2006; Bonnie and Zelle, Reference Bonnie, Zelle, Mastroianni, Kahan and Kass2019; Millum et al., Reference Millum, Campbell, Luna, Malekzadeh and Karim2019). They are also commonly forced into treatment without their consent and without access to protect their rights. Some are even denied their civil and political rights and are discriminated against when it comes to citizenship, education, employment, transportation, housing and access to health care and the legal system. WHO considers human rights violations of people with disabilities (physical and intellectual) to be an emergency in global health that needs attention. Widespread human rights abuses are still observed in mental health institutes, hospitals and in the communities even after the 1960’s deinstitutionalization movement (Bonnie and Zelle, Reference Bonnie, Zelle, Mastroianni, Kahan and Kass2019; WHO, 2019; 2022).

In response to the abuses and violations, some countries have started to integrate health, mental health and human rights into medical education. To illustrate, The Health Professions Council of South Africa has placed a mandatory human rights course in higher education institutions (London et al., Reference London, Baldwin-Ragaven, Kalebi, Maart, Petersen and Kasolo2007) after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had identified that several healthcare professionals participated in cruel and unethical practices with their patients, despite their commitment (Hippocratic Oath) to safeguard their lives and to condemn methods violating human rights. Creating health equity and adhering to ethical principles are competencies expected and highlighted in the GMH domains (Buzza et al., Reference Buzza, Fiskin, Campbell, Guo, Izenberg, Kamholz, Hung and Acharya2018), in the ICDDP (International Association of Applied Psychology and International Union of Psychological Science, 2016) and the UDEPP (IUPsyS, 2008). In fact, psychologists and healthcare professionals working toward health equity, in its broad sense (including mental health), are advocating for the right for equal access to health and mental health services, on behalf of underrepresented, vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals, people and communities – e.g., low-income societies, refugees, displaced, asylum seekers, immigrants, homeless, racial, and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+, individuals living with disabilities, chronic and debilitating (life-threatening) disorders, statelessness persons, among many other groups. As noted in the WHO’s (2022) report, deficient infrastructure and poor access to mental health care are significant structural risk factors associated with the development of mental health disorders, whereas social justice, inclusion, integration and human rights-based care are considered protective structural determinants.

Successful transformational change in GMH requires creating innovative curricula in psychology and other related fields based on human rights, social justice and advocacy models. This movement is already observed in the fields of medicine psychology, social work, nursing and public health, as several graduate programs (discussed in the GMH education section) were launched integrating human rights, social justice and advocacy in GMH. Embedding GMH into the academic curricula is a social responsibility (WHO, 2022). Psychologists and professionals in the GMH field can and should propose innovative solutions to address the disparities contributing to the GMH crisis, promote the determinants of health and mental health, protecting the rights of people with mental health disorders, engage in advocacy and social justice initiatives to demystify mental health disorders and ensure that all are treated with respect and dignity, encourage commitment and empowerment and combine efforts participating in interprofessional projects promoting capacity building to combat stigma and discrimination. The need to train new and senior health specialists in the area of GMH throughout their careers has increased and will continue to grow exponentially especially considering the ongoing challenges around the world, and the WHO comprehensive mental health action plan proposed for the next 17 years to invest in transformational GMH (Bakshi et al., Reference Bakshi, James, Hennelly, Karani, Palermo, Jakubowski, Ciccariello and Atkinson2015; Weir, Reference Weir2020; Rajabzadeh et al., Reference Rajabzadeh, Burn, Sajun, Suzuki, Bird and Priebe2021; WHO, 2022).

Teaching health policy and health management

In 2001, the WHO released a report on World Health that focuses on mental health. It suggested several solutions to the problems of GMH including establishing national policies and legislation. In fact, the WHO’s (2022) report put forward the inseparable links between mental health and public health, specifically human rights and socioeconomic development. This indicates that the transfiguration of policy and practice in mental health has a positive impact on individuals, societies and countries at large. Thus, contributing to mental health can improve the lives of everyone. The literature has shown that the ideal approach to building capacity in global mental healthcare will require partnerships amid professional resources in high-income countries and encouraging health organizations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Fricchione et al., Reference Fricchione, Borba, Alem, Shibre, Carney and Henderson2012). The result of these partnerships will be sustainable academic relations that can instruct a new generation of primary care physicians, psychologists and others, ultimately, health specialists. Researchers claim that it is a crucial educational component to teach health policy and practice, in training and to promote better intervention, prevention and strategies. Sola et al. (Reference Sola, Kothari, Mason, Onumah and Sánchez2019) proved in her article that by looking at health policy through the lens of academia, trainees were able to develop a new perception on how health policy activities can contribute to teaching, publications and leadership opportunities. When health policy was incorporated into the teaching, students were better situated to integrate health policy skills in their scholastic and professional careers as well (Sola et al., Reference Sola, Kothari, Mason, Onumah and Sánchez2019).

In the past 20 years, there has been increasing overlap between the agendas of the government and the department of health, and the aims of health psychologists in many regions in the world. This has often included exploring factors behind behaviors and evaluating interventions established and studied that aim to change health behaviors for individuals, groups and the community (Abraham and Michie, Reference Abraham and Michie2005). This most notably may lead to additional funds for healthcare services, as interventions and strategies for disease prevention and healthcare maintenance would develop and become more efficient, reducing sickness costs. At the community level, these strategies would also lead to more public engagement and by extension trust in the healthcare system due to greater and more comprehensive knowledge and awareness of health. Such a process may then lead to an improved level of health in the general community and to project developments aimed at developing higher quality and more preventative services.

The synchronous systems model, a theoretical and clinical approach that defines and includes individual differences in people and settings, could support healthcare services and influence policy. Within this model’s scope, cost effectiveness and medical efficacy may improve and become more efficient, suggesting psychologists may play a central role in the triage of medical services and healthcare policies. Gregerson (Reference Gregerson1995, p. 1) explains: “The Synchronous Systems Model provides theory, supportive data, and clinical assessment devices to strengthen clinical psychology’s role in medical settings.”

Further models since then have also been developed offering more opportunities for psychologists to develop their roles in treatment. For those models to be applied effectively, psychologists must become more interdisciplinary, familiar with the healthcare culture, expand and adjust their skill sets, maintain collaboration with other health discipline as well as have a larger perspective for advocacy (Johnson and Marrero, Reference Johnson and Marrero2016).

Psychologists have been able to successfully change federal statutes in the USA in the past 20 years. However, some obstacles and limitations have remained clear. In an article published in 1995, DeLeon and colleagues explained that Health Psychology was still very often overlooked at the time and that clinical psychologists’ interventions were often prioritized. They continued: “federal health policy decisions, including management of excessive federal health spending will dictate the growth and opportunities for health psychologists” (DeLeon et al., Reference DeLeon, Frank and Wedding1995, p. 493). A talk presented at a conference on The Socially Responsible Psychologist – A Symposium in Honor of M. Brewster Smith, held at the University of California, Santa Cruz, on April 16, 1988, was published in a paper in 2021 (Kelman, Reference Kelman2021) again in support of the need for psychologists in policy. It discussed the socially responsible citizen when it came to policymaking and speaking up and the similar concept of the socially responsible psychologist. In line with that article, a responsible citizen is one that brings independent judgment on policy process and assesses policies with an independent view as per their values, with the aim of citizens having a more active say in government and determining policy. These aims intersect with the role of the socially responsible psychologist, but distinctly psychologists may bring an alternative perspective given their specified knowledge and experience in their field, in the evaluation of policy. Therefore, psychologists must meet their “citizen obligations” with the added value of their knowledge to the essential role of changing policies for the needs of the community in order to protect the public (Kelman, Reference Kelman2021).

Finally, Friedman (Reference Friedman2006) explains that for efforts to truly be successful, effective and clearly understood, psychologists must have a comprehensive understanding of policy, government and research. For that he suggests more training for graduate students that would include policy-related issues, an increase in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary training and research and “by integrating the principles and concepts of complex adaptive systems within research and training, and by diversifying research methods to allow careful study of important policy and systems issues” (Friedman, Reference Friedman2006, p. 6).

When looking at the implementation strategy of such programs, it is important to focus on applying hybrid designs for better knowledge regarding the effectiveness of interventions in diverse environments. Such designs and interventions target adaptability in different areas, task division, supervision and training, along with fidelity checks and looking into retention rates and follow-up with participants (Meffert et al., Reference Meffert, Neylan, Chambers and Verdeli2016).

Recently, the limitations are also being addressed as some universities opened a department for health policy and management with courses dedicated to this field. This department does offer courses that are available for students that are in psychology graduate programs; however, they are electives. For example, in the University of South Hampton, UK an international social policy course exists within the program of Health Psychology. This course exposes students to policymaking and planning, yet not specific to health policy. On the other hand, other universities such as Northwestern University, USA offer a master’s degree in health psychology that includes a specific mental health policy elective. This pattern also appears in several other programs in Europe, United Kingdom and the USA.

Teaching leadership skills

Teaching leadership skills in graduate psychology programs is also necessary since psychologists tend to find themselves serving leadership positions in the community that they are not always prepared for. Based on the APA ethical code of conduct, psychologists are dedicated to integrity, justice, fidelity and responsibility in practice, as well as the use of psychological knowledge for the benefit of individuals and society (American Psychological Association, 2010). Teaching leadership skills during higher education can support the future implementation of psychologists’ knowledge in an informative way. Psychologists in training can be influenced by learning the following fundamental leadership qualities: self-awareness, congruence, commitment, cooperation, shared purpose and handling conflict with civility (Kois et al., Reference Kois, King, LaDuke and Cook2016). Leadership activities enhance student training by developing professional identities, and organizational and communication skills that are vital for service provision and advancement, as well as professionally with colleagues. Various psychology doctoral programs, internships and postdoctoral residency guidelines provide students with leadership roles; however, there are still no explicit requirements for acquiring such experience. Clinical psychology training programs and mentorship beyond sole academic guidance are central to psychology students’ journey to leadership development. This also allows for opportunities for student involvement in departmental policies as well as learning modeled leadership behaviors from faculty mentors (Kois et al., Reference Kois, King, LaDuke and Cook2016). Nonetheless, it is important to note that access to education remains a barrier in the 21st century. In a study conducted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), high tuition rate was identified as one of the most important obstacles to achieve universal access to higher education. Provision of funds (private and governmental) is crucial to address this problem supporting the training of competent professionals especially in LMICs (UNESCO, 2020).

Conclusion

It is necessary to acknowledge that the internationalization of such a curriculum faces barriers that slow the process down, particularly regarding the educators’ time limitations, enthusiasm and other commitments that might get in the way of developing an international psychology course (Stevens and McGrath, Reference Stevens, McGrath, Rich, Gielen and Takooshian2017). Educators are encouraged to advocate for the internalization of the psychology curriculum, as well as communicate its importance to students, faculty and affiliated institutions. The goal of international psychology courses is to familiarize students with non-Western research and phenomena while pushing them to critically assess how global events affect psychosocial experiences.

Psychology education in the 21st century must provide psychologists in training the knowledge and skills to fulfill the needs of individuals and communities worldwide. Widening the curricula scope to include social justice, human rights, advocacy and health policy and management will be preparing the new generation of psychologists to be GMH professionals who can offer their services and expertise wherever they are needed, with cultural humility and respect making them role models for other health professions.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.11.

Author contribution

B.K. is the main contributor, and V.D.C.P. has contributed significantly to the development of the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments

August 1st, 2022

Dear Editor of the Cambridge Prism series,

I am happy to submit this manuscript titled: “Transforming Psychology Education to Include Global Mental Health” to the journal of Global Mental Health.

My co-author and I think that this article will be an important addition to the literature on global psychology and education, which will hopefully highlight the future of psychology worldwide with a focus on the preparation of young psychologists in training to become global psychologists.

This manuscript has not been submitted to any other journal and is our original work.

Thank you for all your support

Best,

Brigitte Khoury, PhD