‘Statistics? You can prove anything with statistics’ – Sir Humphrey Appleby, Yes Minister (TV Series).

The establishment of international organizations in the wake of the First World War came hand in hand with the rise of new statistical, quantitative, or scientific forms of global governance. As important arbiters of international standards and regulations, international organizations derived legitimacy from their seeming neutrality and ability to mediate inter-state disputes with impartiality. Global statistics offered a critical tool through which international organizations could categorize member-states and shape international regulatory frameworks. In doing so, some organizations hoped to elevate their work over others by distinguishing themselves as ‘technical’ organizations over their more political counterparts.

Despite the hopes of what a new era of international statistical administration could offer, attempts to create metrics were heavily flawed, often reflecting European preconceptions of the model state. In this article, I present one of the earliest examples of such a clash over the definition of a state of ‘Chief Industrial Importance’ in the early years of the International Labour Organization (ILO) between 1919 and 1922, which would determine the composition of its Governing Body. In this clash, a non-European member-state, India, challenged the implicit Eurocentricity of these metrics in a bid for a seat of its own. It did so on the basis that industrial importance be determined through aggregate statistics that judged the size of a state’s economy over its relative development.

The early twentieth-century Western international system used economic development as an important indicator of ‘Civilizational’ progress.Footnote 1 The development of a capitalist market economy, mechanized industrialization, and higher labour standards became significant demarcations of this advancement.Footnote 2 International organizations became new forums through which non-European states, traditionally deemed by European states as ‘backwards’, could challenge the inequalities imposed on them in the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 However, rather than providing a global forum to challenge European hegemony, international organizations recreated many of what Vincent Pouliot calls ‘Pecking Orders’ in international society.Footnote 4 Despite the incorporation of many non-European states into early international organizations, European states would continue to use their political power and, in the case of the ILO, their relative economic advancement to maintain a position of predominance within international organizations.

By confronting this status quo, the Indian delegation ignited a politics of statistical definition, as different states gerrymandered the definitions of these metrics and the data upon which they were built to find a favourable classification. However, India’s dissent against the composition of the Governing Body was not directed by a delegation from an independent state but as a British colony attempting to secure another seat for the British Empire on the Governing Body. This aspect transforms what seems like a history of India, challenging the European world order into how Britain used India’s unique economic aspects to expand its influence.

Due to its position within the British Empire, many documents outlining India’s bid for a seat on the Governing Body are found in the archives of the India Office at the British Library in London and the National Archives of India in Delhi. There is little pre-existing literature on this historical episode; thus, this study relies heavily on archival documents. These largely cover the perspective of the Indian delegation, as well as documents from the archives of the ILO and League of Nations in Geneva to reconstruct this little-known history.

The significance of this study is that it delves into one of the earliest attempts of an international, technical organization attempting to create a statistical framework for its governance. It reveals many contemporary issues that international organizations continue to face today. Despite several decades of decolonization, binaries such as ‘industrialized/ non-industrialized’, to ‘developed/ developing’ continue to play a significant role in assigning significance at international organizations. Major international matters, from combatting climate change to determining the implementation of international trade agreements, continue to use development status as a barometer.Footnote 5

In an unusual role reversal, some states have used their ‘developing’ status as an advantage at international organizations. At a Press Conference at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2019, then United States President Donald Trump thundered that: ‘China’s viewed as a developing nation, India’s viewed as a developing nation […] as far as I’m concerned, we’re a developing nation too’.Footnote 6 In this context, the United States attacked large developing economies that claim ‘special and differential treatment’ at the World Trade Organization, which offers developing states longer implementation times and more safeguards than other member-states.Footnote 7 In its stead, the United States has proposed a new standard to measure developing status, replacing the ‘outdated dichotomy between developed and developing countries’.Footnote 8 The United States’ desire to replace a self-declaratory model of developing status with a statistical measurement reveals the continued reliance on international organizations to provide neutral, statistically driven tools to settle international disputes. However, this article will show that any attempt to create such a standard will likely repeat the politicization of metrics as befell the ILO a century ago.

The rise of statistical international organizations

Founded in 1919, the League of Nations was not the first international organization, but it deeply expanded the scope of its activities from its forerunners. The League’s agencies, such as the Labour and Health Offices, later to become the International Labour Organization and World Health Organization, inaugurated a new epoch of global governance through ‘world economic statistics’.Footnote 9 This involved collecting, centralizing and standardizing vast quantities of economic and sociological data that could be used to create better comparative standards and regulations between member-states.Footnote 10

Similar attempts to utilize statistics in major inter-governmental congresses had occurred prior to the establishment of the League. From 1853 to 1876, several International Statistical Congresses were held, later being relaunched and regularized in 1885 as the International Statistical Institute.Footnote 11 The discussions held at these congresses aimed to push states towards better means of data collection and towards an increasingly statistical means of governing, from regularizing censuses to collecting data on the spending habits of the poor. Even in 1853, it became clear that a dichotomy was growing between topics that were considered more political, such as questions on the extent of the state’s intervention in public life, and questions deemed as more technical and less contentious such as trade, poverty, and crime. Yet these topics also rapidly proved to be just as political and more difficult to resolve than initially anticipated.Footnote 12

The growth of statistics in national administrations would also rapidly find its way into early technical organizations that predated the League or the ILO. The International Telegraph Union (ITU), established in 1865, and the Universal Postal Union (UPU), founded in 1874, played integral roles in regularizing the costs of international communication, requiring clear statistical data on questions such as the number of telegraph lines and the usage of postal services.Footnote 13 The influence of this statistical approach became increasingly evident at major international conferences, including the second Hague Conference (1907), where similar economic statistical measures were presented to determine the number of judges representing each country.Footnote 14 Before the advent of the League in 1919, statistics were a natural tool for international organizations, helping to arbitrate various issues from expenses to voting power.

The League dramatically expanded the scope of the work of an international organization, both in the depth of its mandate and in the width of its membership that encapsulated most of the world. To manage such a wide range of responsibilities, the League required a large corps of international functionaries to work at its Secretariat. The same applied to the League’s agencies, such as the ILO. A significant role in the work of this international bureaucracy was data collection, where the League proved to be a crucial focal point of international data collection.Footnote 15 The League was thus inculcated by the union of the drive for greater statistical governance with the Weberian ideal of a modern, ‘rational’ bureaucracy to carry out its global governance.Footnote 16 In doing so, the League and its agencies would lay the cornerstones for the ‘functionalist’ theory in international relations, prizing scientific and technocratic global governance over the self-interest of states as argued by ‘realists’.Footnote 17

In some aspects, however, the League was more overtly political than earlier international organizations such as the ITU and UPU. The permanent membership of its executive body, the League of Nations Council, a precursor to the UN Security Council of today, was selected from the victors of the First World War rather than by any scientific standard. The 1919 Paris Peace Conference that established the League and drafted the Versailles Treaty had been dominated by the ‘Big Five’ that would secure their position in the League Council: the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan.Footnote 18 To redress this political imbalance, the League Assembly voted for several rotating Council members every three years, all of which would have veto powers (unlike the UNSC of today). The League Assembly was once again an inherently political arena, where different states competed for the votes of other member-states to participate on the Council.Footnote 19

As an agency of the League, the British representative on the Labour Committee of the Peace Conference wanted to see the ‘Big Five’ of the League Council gain a permanent foothold in the Governing Body of the ILO. This was resisted by Belgium’s representative, Emile Vandervelde, who did not believe that being a war victor was a qualifier for permanent membership of the Governing Body.Footnote 20 In its stead, permanent membership would be determined by states of ‘Chief Industrial Importance’. This term was not to be defined by diplomats at the Peace Conference but by a specialized committee of experts initially based in London. In doing so, the ILO and the League created a new dichotomy among international organizations, as the ILO attempted to present itself as a more ‘technical’ organization than the more overtly ‘political’ League.

By breaking with the League’s more overtly political means of determining its Governing Body, the ILO distinguished itself from its mother institution from the outset as more technical, expert-driven, and objective.Footnote 21 By creating a limited number of eight permanent seats on the Governing Body, the ILO’s permanent membership was more dynamic than the League’s, as a state’s position on the Body could be threatened if another state’s economic metrics superseded it.Footnote 22 This would depoliticize the process of appointing the Governing Body, which would reflect the economic progression of states in the future rather than calcifying the Body based on their political situation in 1919.

Despite the differences with the League Council in selecting its Governing Body, the desire to maintain a permanent body of economically advanced states in charge of the organization revealed a note of civilizational, if not developmental vanguardism in the institution. Assuming that the states of industrial significance would generally be leaders in the field of labour regulation, these states—geographically European besides the United States and Japan—could set the agenda and modernize labour relations in less industrially developed states. Arthur Fontaine, the newly appointed Chairman of the ILO’s Governing Body, defended the Governing Body’s composition. He argued that it was better to have permanent members close to Geneva who could easily convene every two to three months without travelling large distances and that the work was largely administrative.Footnote 23

Many member-states deemed Fontaine’s response as inadequate, but what the drafters of the metrics behind Chief Industrial Importance did not predict would be a widescale revolt of states which disagreed with the result of the statistical standard. Many of these came from competing European states who felt unfairly judged by the standard and newly formed European successor states forged out of the collapsed Russian and German Empires, such as Poland. What the drafters had counted on even less was that the principal objection to their standard would arise from a colonial polity from Asia, such as British India.Footnote 24

India’s ‘anomalous’ membership in the international system

The membership of Colonial India and the British Dominions (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa)—domestically self-governing colonies—to the ILO and the League of Nations was a particularly contentious point in the negotiations around the creation of the ILO. Most significantly, it raised concerns among other member-states about the extent to which Dominion membership was independent or directed by Britain.Footnote 25 But among these colonies, India posed a particular set of problems for the question of industrial importance. The Dominion economies, which showed relatively high economic indicators, were more sparsely populated and unlikely to threaten European states for a top role on the Governing Body.Footnote 26 India’s economy, with its vast population and aggregate output, overshadowed all but the biggest world economies, yet its relative metrics were very low compared to European economies.Footnote 27

As British colonies, the accession of the Dominions and India to the League and the ILO seemed to many member-states anomalous – countering the notion of the equality of states and the political independence of states’ actions at the organization. For British negotiators, however, the inclusion of several of their key colonies was seen as the natural balancing of the fact that sovereign equality did not represent the natural inequalities of the Great Powers in world politics.Footnote 28 The opposition to the voting equality of states at international organizations had been increasingly commonplace in British policy, from the 1907 Hague Conference to the Paris Peace Conference, which has often been seen as a form of imperial vote-stuffing.Footnote 29 However, throughout the Paris Peace Conference, much of the impetus for representation came from Dominion leaders, who sought to expand their autonomy and standing in the British Empire and world politics.Footnote 30 Ultimately, these colonies would gain membership through a craftily drafted loophole allowing automatic accession for the original signatories of the Treaty of Versailles.Footnote 31

As signatories of the Treaty of Versailles, the membership of the Dominions and India to the ILO was all but confirmed. However, there was still robust resistance to the idea of the British Dominions and India gaining a seat on the ILO’s Governing Body, considering that Britain was certain to become a state of Chief Industrial Importance once the London Committee had finalized its metrics. In the United States, there was resistance to joining an organization such as the League and the ILO, in which the British Empire commanded six votes.Footnote 32 The American representative at the Labour Conference in Paris, Henry M. Robinson, proposed allowing the individual US States to become member-states, although this draft did not pass.Footnote 33

The Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, a member of the British Cabinet, appointed members of the Indian delegation to the League of Nations and the ILO. The delegation, selected for political loyalty to the British Raj and administrative experience, consisted primarily of British colonial officers, Indian administrators with former experience within the Government of India, and Indian princes.Footnote 34 This would also be the case for India’s delegation to the ILO.Footnote 35 The effort to secure India’s representation on the ILO’s Governing Body was thus not carried out by elected Indian officials, but this amalgamation of Indian ‘loyalists’ led by British bureaucrats.Footnote 36

This umbilical connection between the Indian delegation and the British government played a crucial role in India’s struggle for a seat on the Governing Body. The British government became increasingly concerned about the ILO’s expense and the scope of its activity, warning that it could become a ‘fourth International’ bypassing governments and talking directly to trade unions. Yet some saw advantages in the ILO, believing that its modernization of global labour standards would make foreign powers less competitive and alleviate the ‘dumping of goods produced abroad under sweated conditions’.Footnote 37 By having a separate membership to Britain at the ILO, India was no longer subject to Britain’s Labour Conventions.Footnote 38 Therefore, the separate representation of British colonies at the ILO allowed the disaggregation of the Empire’s international labour reforms through the ILO.

Nonetheless, the Indian delegation’s obvious political connection to a British Cabinet member, the very different nature of India’s economy and its politics to that of the Dominions and Britain, meant that the Secretary of State was reactive to domestic concerns. Throughout the drafting of the Covenant of the League at Paris in 1919, there had been widescale resistance to colonial rule and the maintenance of repressive wartime laws called the Rowlatt Acts that would culminate in the bloody backlash from British troops at Amritsar in April 1919. Moreover, the antebellum period saw the rapid rise of Indian trade unionism, with the foundation of the first registered trade union in Madras in 1918 and the first trade union federation in India, the ‘All Indian Trade Union Congress’ (AITUC), in 1920. The formation of the AITUC had aimed to represent Indian workers delegates to the ILO better, but its formation occurred nearly a year following the Indian delegation’s attempt to challenge the composition of the Governing Body.Footnote 39

Although the India Office attempted to mitigate the effects of growing industrial disputes in India, combined with an exponentially more vocal ‘Home-Rule’ movement, there was also pressure from within India to maintain lower labour standards.Footnote 40 Business owners in India, both British and Indian, enjoyed an opt-out to some of the same labour standards due to India’s lack of industrial development. Meanwhile, India’s 500+ quasi-autonomous Princely states that covered around a third of the landmass of British India claimed to be outside India’s jurisdiction and not subject to ILO resolutions adhered to by India.Footnote 41 By not following ILO labour standards, Indian Princely states aimed to gain a competitive economic advantage over directly governed British territories, putting more pressure on the Government of India to loosen labour regulations.Footnote 42

The Secretary of State for India also saw India’s membership of international organizations as part of a longer-term plan of constitutional devolution for India that had been promised during the First World War. India’s entry into the League of Nations complemented ongoing plans for legislative reform in India by granting India an international personality at Geneva whilst still maintaining control over its delegation.Footnote 43 Similarly, through the ILO, Montagu wanted a symbolic gesture of India’s progression towards better labour regulations whilst simultaneously seeking not to implement those standards by maintaining opt-outs due to India’s lack of development.Footnote 44 He claimed that ‘it is inevitable that the interests of Western and Eastern countries must clash’ and that it was ‘desirable for Eastern countries should be represented on a body which under the Treaty has been vested with important functions’.Footnote 45 For Montagu, it was important for India’s representation to be formally distinct from Britain’s, even if it did not dissent from its line of policy, to assure Indians that the particularities of India’s vast but undeveloped economy were not misrepresented by the necessities of Britain’s own economic goals.

India’s bid for membership on the Governing Body from 1919 until 1921 was therefore not instigated by any elected Indian representative but by British and Indian officials appointed by a British Cabinet member. India’s bid for a place on the Governing Body was thus highly ambiguous. The nature of India’s colonial economy differentiated it from its European competitors. However, its bid for a seat was propelled by British civil servants to multiply its representation and satisfy calls for greater Indian autonomy within the Empire.Footnote 46

The Washington Labour Conference and the first metrics (1919-20)

The Committee assigned at the Paris Peace Conference to define ‘Chief Industrial Importance’ was under pressure to select the new Governing Body before the Washington Labour Conference.Footnote 47 This would allow the Governing Body to be complete by the start of the conference in Washington so that the ILO could begin to implement resolutions quickly.Footnote 48 The Committee met in London to establish the following criteria to assess industrial importance:

The four absolute criteria were:

-

(1) Industrial population (including mines and transport).

-

(2) Horsepower used in industry.

-

(3) Length of railway track.

-

(4) Size of Mercantile Marine.

The three relative criteria were:

-

(5) Relation of the industrial population to the total population.

-

(6) Relation of horsepower to the total population.

-

(7) Relation of railway track to the state’s total area.Footnote 49

The Committee assigned index numbers, awarding 100 points to the state with the highest value in that metric, whilst other states would be given an index based on its value relative to the highest-scoring state. They awarded double points to three of the four absolute criteria: industrial population, horsepower, and the size of the merchant marine but not to railway length. This meant that the aggregate metrics were still considered more important than relative ones to distinguish the larger economies of Britain and France from other European contenders. But the inclusion of three relative indicators would ensure that European economies usually scored higher than non-European ones. Moreover, if the Committee were faced with two states with equal aggregate productive capacity, they would select the state with the smaller industrial population, reflecting its economic development over the other.Footnote 50

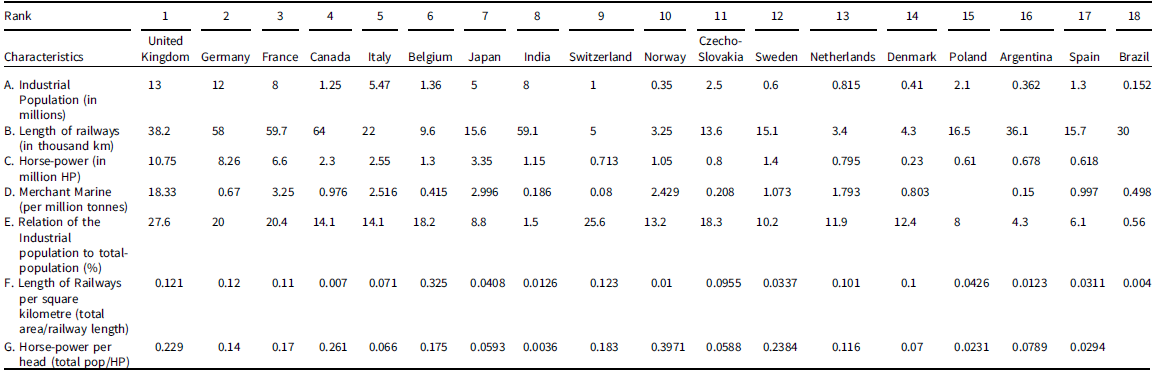

Table 1 reveals a breakdown of the index scores conferred by the London Committee based on the statistics provided in Table 2.Footnote 51 Despite this attempt to avoid automatically granting the ‘Big Five’ of the League Council a permanent position on the Governing Body, all five (the United States, Britain, France, Italy, and Japan) were selected, as well as Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland.Footnote 52 Spain was also chosen as a possible replacement if Germany, deemed a pariah state by many after the First World War, was blocked from taking up membership in the ILO. Despite the double-weighted criteria being absolute values, the Committee had thus returned a highly European Governing Body, except for the United States and Japan.

Table 1. States Classified According to the Seven Characteristics of the London Committee through the use of index numbers (100 being awarded to the highest member-state).Footnote 55

Table 2. Table of statistics of the states of ‘Chief Industrial Importance’

The predominance of European states on the Governing Body was undoubtedly not lost on non-European members of the ILO. Europe had taken a position of preponderance in many international forums prior to the creation of the League and the ILO, marginalizing non-Western states as ‘inferior’ in a series of different areas from culture, law, race, and economic development. Relative economic metrics of industrialization were indicative of this form of ‘Civilizational’ progress and had generally been dismissive of non-Western economies as ‘backwards’.Footnote 53

By the turn of the twentieth century, many non-European states hoped that states such as Japan had begun to disintegrate the binary distinction between Western civilization and Eastern ‘barbarism’ that had defined European international society in the nineteenth century. Japan had successfully repealed demarcating symbols of its perceived civilizational, economic, and legal ‘inferiority’ through its rapid modernization and conformity to Western legal and cultural norms. However, Britain and the United States rebuffed its attempts to introduce a racial equality clause in the Treaty of Versailles. Meanwhile, Japan’s armed forces had humiliated a major European Power, Russia, in a conflict over the Korean peninsula whilst securing an alliance with Great Britain as a nominally sovereign equal.Footnote 54 Therefore, Japan’s membership in the Governing Body was fully compatible with the perception that the Commission was replicating the European world order in its Governing Body.

Nonetheless, complaints about the composition of the Governing Body were not restricted to non-European states. Other European states that had not made the cut felt like the metrics had not reasonably considered their economic situation. Successor states to the former Russian and German Empires, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia, had been effectively excluded for lack of up-to-date statistical data, a rare luxury to acquire in the midst of building a new state in the wake of the First World War and the collapse of Empires.Footnote 56 These nascent states could not easily disaggregate their data from their former empires and had not been considered by the Committee. Similar misgivings were also made to omit China as a state of Chief Industrial Importance.Footnote 57 Other, more established European states, such as the Netherlands and Sweden, were dissatisfied with the Commission’s decision to award seats to smaller European economies such as Switzerland and Belgium.Footnote 58

Whereas other European states challenged their counterparts on similar economic metrics, it was India that raised serious concerns about the definitions of specific metrics, particularly that of ‘industrial population’. The Indian delegation, which had submitted its complaint against the new composition of the Governing Body days after it was selected at the Washington Conference, argued that the Governing Body should include a better reflection of aggregate metrics by having an expansive definition of ‘industrial population’.Footnote 59 India’s Secretary of State, Edwin Montagu, argued that determining the Body based on industrial efficiency would not be ‘equitable’ and that the Committee should select based on the number of workers that the ILO’s industrial regulation would affect.Footnote 60 As the ILO’s work covered the regulation of matters regarding agriculture and industry, the Indian delegation argued that the total industrial population should include agricultural workers. Moreover, the Committee’s definition had excluded many artisanal producers, privileging the more modernized proletarian labour force working with mechanical means of production over smaller workshops and handicrafts that constituted a large but difficult-to-quantify section of India’s working population.Footnote 61

The Indian delegation also argued for a greater diversity of states within the ILO’s European-dominated Governing Body by introducing India as another Asian state alongside Japan. Montagu asserted that India and other Eastern states stood to gain more from a permanent position on the Governing Body because their economies were ‘backwards’. This called into question the overall necessity to have relative economic indicators as a basis for a place on the Body, undermining the belief that European states should act as a vanguard in modernizing labour standards.Footnote 62 China backed India’s complaint, with both states stating that they represented a third of the world’s population. However, China chose not to pursue an official complaint or a seat on the Governing Body at this time.Footnote 63 Both India and China, supported by Siam and Persia, were angered at the lack of the Governing Body’s diversity and refused to vote for the four elected and rotating government positions on the Body.Footnote 64

India’s position began to gain momentum when the South African delegate, William Gemmill, and twenty Latin American states declared their ‘disapproval’ of the near European monopoly on the Body’s composition.Footnote 65 Rather than propping up the European bloc of states, Britain joined the dissenters, a position it stood to benefit from as its position on the Body was not threatened and opened the possibility for more of its colonies to take a place alongside it.Footnote 66 However, the Committee made it clear that although it might be desirable for a diversity of states on the Body, it was incompatible with the statistical standard of industrial importance.Footnote 67

As the Indian delegation began to put increasing pressure on the Organising Committee to disclose how it had created its metric for industrial importance, it became increasingly clear that other political machinations were behind the selection of the Governing Body. The India Office’s connection to the British government made it significantly easier to seek answers from the British representative on the Organising Committee, Malcolm Delevinge. Delevinge admitted that there was little statistical basis for selecting the states of industrial importance due to the difficulty in collecting data prior to the start of the conference in Washington. Instead, the Committee selected states ‘popularly supposed to be of chief industrial importance’.Footnote 68 Under pressure to explain the basis for selection, the Committee responded that they had selected two very different economies, such as Belgium and Spain, based on their industrial development. The Committee chose Switzerland for its historic role in regulating labour issues.Footnote 69 Japan, which had a rapidly transitioning economy, was chosen for being ‘one of the Great powers’ and for its commercial position in East Asia.Footnote 70 The Committee had thus clearly deviated from its own metrics when assigning states but refused to be moved by complaints made after the selection.

The Committee had also faced immense political barriers in awarding seats to India and Canada. United States representative, Mr Robinson, opposed the inclusion of India or Canada on the Governing Body. American public opinion was turning against the notion of the United States adhering to an international system wherein the British Empire wielded six votes to their one.Footnote 71 As the Conference in Washington was underway, the United States Senate refused to ratify the Versailles Treaty, blocking the United States’ admission to the League. The British Ambassador to the United States, Viscount Grey, aimed to mediate the solution by considering the Lenroot Reservation, which would allow the United States to ignore any League decisions on which multiple parts of the British Empire had voted.Footnote 72 Later calculations would show that India was far ahead of Switzerland in its metrics of industrial importance. Still, American suspicions of British hegemony in the international system would play a prominent role in excluding India from securing a position on the Governing Body.Footnote 73

With growing certainty that the United States would not join the League nor the ILO, the newly appointed Governing Body (rather than the Committee that had defined industrial importance) decided that Denmark would temporarily preside over the United States’ seat. Rather than being chosen on a statistical basis, as several states outranked it, the Governing Body selected Denmark due to it almost being voted as a rotating member of the Governing Body and a desire to represent a northern European country.Footnote 74 But it was a perplexing choice for many, particularly the Indian delegation, which found the decision ‘patently unjustifiable’, with several states, including India, ranking higher than Denmark (see Table 1).Footnote 75

The Indian delegation complained that the selection of Denmark was a deviation from the statistical standard of industrial importance. Due to its population size, India was ranked as a ‘first-class’ state at the League, which determined its financial contributions. The Indian delegation thus threatened to reduce its contributions to the ILO if it did not abide by its own statistical standard to determine the Governing Body.Footnote 76 The Organising Committee responded by stating that there was insufficient statistical data to accurately calculate the metrics, especially as the war had warped the economic data in many countries. The Committee asked the Indian delegation to wait until 1922 when the new non-permanent Governing Body members would be selected.Footnote 77 Impatient, the Indian delegation attempted to gain Argentina’s rotating seat on the Governing Body, as Argentina had essentially withdrawn from the League and the ILO and refused to pay its membership fee. The League’s Secretary General rebuffed the idea, allowing Argentina to carry on its mandate in absentia.Footnote 78

Despite the ILO’s early attempts to distinguish its selection of the Governing Body as depoliticized compared to the League, it was still intricately tied to its mother organization through the League’s Covenant. Failing to gain the ILO’s support for membership of the Governing Body, the Indian delegation called upon the League Council to intervene, denouncing the ILO’s selection proceedings as ‘irregular and open to challenge’.Footnote 79 Under Article 393 of the Versailles Treaty, the Council of the League of Nations was to respond to any question over which member-states constituted states of Chief Industrial Importance. However, many of the ILO’s Governing Body’s permanent members also presided over the League Council. The Indian delegation needed to make an overwhelming case for the primacy of aggregate criteria over relative ones if it were to dislodge other states from the Governing Body.

At the meeting of the League Council at San Sebastian, the British delegate, Arthur Balfour, unsurprisingly sided with India gaining a seat, stating that its ‘peculiar’ position as a large but relatively undeveloped economy could be of service to European states.Footnote 80 India’s calculations for its industrial population alone would dwarf all its European competitors.Footnote 81 Predictably, the European states on the League Council, Italy and France, did not share Balfour’s opinion that India’s membership would benefit them and urged that a better selection of metrics be selected to define Chief Industrial Importance. Deeming that a reconfiguration of the ILO’s Governing Body during its first tenure would be ‘inexpedient’, the League Council ruled that new metrics should be drafted for the Governing Body’s next term in 1922.Footnote 82

Corrado Gini and the intervention of the ‘expert’ (1920-22)

The Committee and the League Council’s dismissal of states’ grievances towards the Governing Body’s definition of industrial importance undermined the ILO’s legitimacy as a scientific and expert-driven institution. The Indian delegation was convinced that its exclusion had been purely political and not based on any reflection of its economic output.Footnote 83 To increasingly discredit the selection procedure, the Indian delegation raised the issue at the League’s Assembly, which consisted of all member-states. It was not within the Assembly’s prerogative to adjudicate the decision, but the Indian delegation wanted to leverage the court of inter-state opinion to bear on the Council.Footnote 84 However, the Council deemed any unilateral attempt by a state to change the metrics risked rendering the Governing Body ‘unconstitutional’ and throwing ‘doubt upon all the work done by the Office to the present’.Footnote 85

The ILO was faced with a stark choice. Either to abandon the idea of using a statistical standard such as industrial importance, or to change the metrics. The ILO’s Committee in charge of constitutional reform seriously considered abandoning industrial importance but safeguarding permanent membership for six states: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and, if it were to join in the future, the United States.Footnote 86 This would have made the ILO’s selection process no different than the League of Nations Council. Instead, the ILO’s Committee chose the latter and sought to pursue a seemingly more scientific set of metrics. To appeal to expert authority, the Committee appointed the economist Corrado Gini to begin drafting new metrics. Gini, later the author of the income inequality measuring coefficient that bears his name, was already a renowned statistician who had dedicated much of his recent statistical work towards the Italian reconstruction in the wake of the war.Footnote 87 Through the publication of his new journal, Metron, Gini became the standard-bearer for new forms of statistical, quantitative, and ‘scientific’ governance, which would later underpin the economic policy of Fascist Italy in the 1920s.Footnote 88

Gini requested data from five indices from its member-states: aggregate private wealth, the value of production, the value of the state’s properties, the state’s total public debt, and local government debts. These metrics were to be calculated for the years prior to the First World War, thus judging countries’ applicability on their pre-war economies, discounting either the damage or industrial development incurred during the war.Footnote 89 Yet, statistics before 1914 were difficult to collect. The Government of India had stats regarding its public debt but admitted it a virtual impossibility to accurately calculate India’s private wealth and production.Footnote 90

India was not the only state that had difficulty in supplying statistical data. When Gini’s commission finally released its report, it adopted a broader spectrum of metrics to reflect available data, leading to eight criteria over what had formerly been seven. The four absolute indices would be:

-

(1) The number of workers in each State who require protection by international regulation of labour conditions;

-

(2) The number of workers who emigrate from or immigrate into the State, a number which can in practice be taken to be the same as the total figures for immigration and emigration;

-

(3) The value of the total net production – that is to say, the value of the income of the nationals of the State, deducting the income derived from external sources and adding the income of foreigners which is derived from the country itself;

-

(4) The value of exports and imports — that is to say, of the special trade of the country, excluding transit trade.

The four relative indices were:

-

(1) The ratio between the number of workers in each State and the total of the adult population, a coefficient proportional to the number and effectiveness of the regulations which protect him being applied to each worker;

-

(2) The ratio between the number of workers who emigrate or immigrate and the total population;

-

(3) The ratio between the total net production of the country and its adult population;

-

(4) The ratio between the amount of special trade, and the value of the total net production.Footnote 91

Rather than focus on various industrial categories, Gini’s were considerably more anthropocentric by including immigration as a determinant of industrial importance. However, Gini’s interpretation of whether the term ‘industrial’ covered agricultural producers was relatively narrow. Industrial activities were defined by their ‘intensity’ and ‘specialisation’, with the ILO’s role being to regulate the relations between capital and labour. Therefore, only some agricultural roles, such as distillery workers, could be considered ‘industrial agriculture’, whilst small-scale handicraft manufacturing continued to be omitted.Footnote 92 Moreover, Gini rejected the claims from member-states like India that the Governing Body should be geographically diverse, saying it ran against the spirit of the Versailles Treaty, and that the Commission was solely concerned with industrial development.Footnote 93

Ultimately, Gini’s criteria were discarded. The ILO’s Committee, established to investigate India’s complaint, deemed that though Gini’s metrics were superior to the original ones used in 1919 by the Committee in London, these statistics were still too difficult to collect accurately. Following Gini’s letter in June 1921 to ask member-states for a new set of statistics, the League’s Secretary-General Eric Drummond was obliged to follow up with states that had failed to procure them adequately.Footnote 94 India, in particular, had issues procuring statistics for Gini, especially for calculating India’s aggregate wealth. Moreover, the Indian delegation wanted post-war statistics to be used over pre-war ones, considering India’s economy had been less affected by the conflict than other states.Footnote 95 Therefore, the Committee decided to retain the original set of metrics provisionally until more accurate statistics could be provided for the future.Footnote 96

The Indian delegation welcomed the decision to remove Gini’s criteria, but it was far from a decisive development. The Commission had proposed two possible ways to tally the criteria. The first was to retain the system of index numbers that both the London Committee and Gini had utilized. The other would be to rank states based on the different criteria, removing the more precise use of index numbers altogether.Footnote 97 These two opposing forms of calculation significantly impacted India’s chance of being in the top eight states of industrial importance. Using index numbers, India was placed eighth, effectively replacing Switzerland as a permanent member of the Governing Body. However, the ranked system produced a very different result: India was eleventh, behind Sweden, Czechoslovakia, and the Netherlands.Footnote 98 Both indices and ranking were weighted towards aggregate criteria, yet, some in the Indian delegation feared that other states could change the balance through ‘a series of jugglery’ with statistics that could give greater weight to relative criteria over absolute ones.Footnote 99

Another concern for the Indian delegation was to overturn Gini’s limited definition of ‘industrial labour’, which excluded agricultural workers, maligning the Indian delegation’s efforts for a seat on the Governing Body. The ILO insisted on omitting non-industrial agriculture from the first criteria of industrial population.Footnote 100 By omitting artisans and most forms of agricultural labour, the ILO drastically cut down India’s claim of 20 million industrial workers to 8 million, putting India’s industrial population in joint third position with France and behind Germany and Britain.Footnote 101 The Indian delegation was furious with this definition. One delegate angrily noted that: ‘one might almost believe that the statisticians had exhausted their ingenuity in devising tests that would be unfavourable to India’.Footnote 102

The gravitation of the debate towards what constituted industrial labour revealed that the statistics themselves could be drastically altered based on the definitions of the metrics. This was well exemplified when the newly inaugurated Permanent Court of International Justice intervened in what was a separate matter of whether the ILO regulated agricultural labour. However, the Court’s decision, ruling that the ILO was competent in regulating for agricultural labourers, had a significant impact on the Indian delegation’s decision to further press the claim of its industrial importance through its working population.Footnote 103

India’s appeal to the League Council (1922)

The Court’s decision gave India significantly stronger grounds to press home its case of industrial importance at the scheduled meeting of the League Council in August 1922. Moreover, unlike other claimants to the seat at the ILO’s Governing Body, the Indian delegation had Britain’s political support at the League Council. The League’s Secretary, Eric Drummond, urged the Indian delegation to leverage its position within the British Empire to keep the meeting purely among League Council members and have the British representative Arthur Balfour make the case for India.Footnote 104 Balfour telegrammed back to claim that he could not represent India as the Council was a Court of Appeals in this matter. Instead, the former Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford would defend India’s case.Footnote 105 Nonetheless, it did not mitigate that Balfour’s presence at the Council meeting as the British representative would prove decisive.

Britain’s Labour Ministry, seeing an opportunity of gaining not just an Indian seat on the Governing Body if it pressed its claim but also a Canadian seat, began to argue more ardently for their inclusion. Arguing for both India and Canada on a statistical basis was difficult, as they seemingly represented the opposite side of the absolute/ relative spectrum of industrialisation. However, Canada was ranked first in terms of its railway length and performed well on relative indicators, whereas India only performed well on the total industrial population. Moreover, the British saw Canada’s accession to the Governing Body as a means to satisfy calls for greater geographic diversity in its composition, with Canada replacing the United States as a North American board member.Footnote 106

The Indian delegation also wanted to rule out the ranked system of deciding states, which they deemed ‘hopelessly unscientific’ favouring index numbers, guaranteeing India the eighth seat on the Governing Body.Footnote 107 And finally, in a bid to fully ensure India’s acceptance to the Governing Body, the Indian delegation attacked the use of relative criteria altogether as flawed:

The Committee’s system of grading is such that it would easily be possible to construct, in the garden of the Palais des Nations, a model State […] its railway system could barely be constructed there; its industrial population could easily be accommodated on one chair, and its total population on two; but it would be graded, under the system advocated by the Committee, as the fourth State of chief industrial importance in the world.Footnote 108

Armed with the Court’s ruling on the ILO’s competency over agricultural labour, the Indian delegation aimed to ‘demolish’ Gini’s definition of industrial population.Footnote 109 Rather than accept the figure of 8 million that Gini had calculated, the Indian delegation argued that its industrial population consisted of 12 million industrial workers and an additional 25.8 million agricultural workers. They argued that industrial population constituted the most important criteria, constituting the ‘human-element’ in the six criteria in keeping with the spirit of the Treaty of Versailles.Footnote 110 Similarly, rival states attacked the metrics that didn’t suit them. For Poland, with its limited access to the sea through the Danzig corridor, the metric on the size of the merchant marine was particularly egregious, and wanted it ruled out altogether.Footnote 111

Despite the official appeals to reconsider the statistical basis for industrial importance, the Indian delegation had grown to learn that the process of acceding to the Governing Body would ultimately be a political one. Besides the attempts to justify India’s industrial importance based on its large agricultural population, the Indian delegation reinforced their claims by threatening their budget allocation to the League of Nations.Footnote 112 However, this line of attack was carried out more privately by India’s representative, Lord Chelmsford, in a statement to the Council rather than in the more widely available written memorandum distributed to other states.Footnote 113 The Indian delegation did not want to be seen openly deviating from the technical goal of reinterpreting ‘industrial importance’ by engaging in the more political matter of threatening budgetary allocations.

Other political factors still played a significant role. Chelmsford highlighted India’s wartime contributions, which had played a decisive role when allocating seats at the League Council during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.Footnote 114 However, the Council was still indecisive on the matter. There was pressure within the ILO to oppose India’s seat at the Governing Body, with the ILO’s Director, Albert Thomas, stating the rudimentary nature of India’s trade union movement made it unfit for permanent membership of the Governing Body.Footnote 115

Sensing a turning of the tide, the Swiss representatives feared for their seat on the Governing Body. Swiss representative Giuseppe Motta argued against the Committee’s statistical basis, but from the counter perspective to India, arguing that relative economic advancement was a better metric of industrial importance than total output. They argued that Switzerland’s history and political importance in international labour legislation should be the key factor in Switzerland retaining its seat.Footnote 116 Under pressure to conclude the new composition of the Governing Body before the Labour Conference began in October, the League Council met again in private on 22 September 1922. The Council did not take the case of other petitioners as seriously as India’s, especially Poland’s, which supplied new statistics that placed itself as the eighth state of industrial importance rather than India.Footnote 117

France was concerned that the inclusion of India and Canada would lead to a preponderance of British imperial states on Governing Body. British representative Arthur Balfour swatted away these accusations stating that the discussion was not a political one ‘in any sense’, but rather an industrial one. He retorted that India and Canada regulated their own economic affairs and labour legislation, making them distinct from Britain. Balfour argued that India’s position on the Governing Body was ‘common sense’ and could accelerate its adoption of western industrial standards.Footnote 118 Perceptions, rather than statistics, ultimately won the day for India. French representative Monsieur Hanotaux conceded that ‘if the man in the street were asked whether Sweden or India were the greatest industrial state, he would decide in favour of India’. The Council decided to appoint India and Canada to the Governing Body, at the expense of Denmark and Switzerland.Footnote 119

The decision by the Council to appoint the members, rather than confer with the ILO, led to a clash between the ILO’s Director Albert Thomas, and the League’s Secretary General Eric Drummond. This row between the seemingly technical ILO and the overtly political League centred on the heart of the matter of industrial importance: whether it was an adequately scientific standard and whether the Council had the right to overrule the ILO on the matter. The Council’s report, which was finally published on the 30th September, stated that despite trying to find a statistical definition of industrial importance, political considerations also had to be taken into account.Footnote 120 Drummond too, had stated that any statistical standard of industrial importance would be ‘violently attacked’ by one state or another as ‘unscientific’.Footnote 121 This fear seemed confirmed when another contender for the Governing Body, Spain, complained that the Committee had not adequately calculated its industrial labour force or railway length, but the Council’s decision had already been set.Footnote 122

Albert Thomas was stunned by Drummond’s dismissal of the ILO’s right to choose its Governing Body, calling his position ‘inadmissible’.Footnote 123 Thomas believed there was a different interpretation of Article 393, the Article used for the League Council to resolve the matter, based on its French and English text in the Treaty of Versailles. Thomas, a Frenchman, believed that in French, the text allowed the Council the right to advise on the new Governing Body but not decide it.Footnote 124 Drummond, an Englishman, stated that ‘nobody is better aware of the extreme obscurity of Article 393’, but that his interpretation was correct.Footnote 125 This spat reveals how far the original hope of a statistical standard had deviated into not only a politics of definition but a politics of defining which institution had the authority in deciding who sat on the Governing Body.

Thomas feared that states would be dissatisfied by redrawing the Governing Body by simply reinterpreting the original metrics of the London Committee without either replacing them or introducing new metrics. This could lead to new disputes over the composition and further reliance on the League Council to resolve them.Footnote 126 In an attempt to mark the Organization’s autonomy and end the incessant bids for the Governing Body, the ILO’s Commission on Constitutional Reforms presented a significant amendment that limited the reserved seats of Chief Industrial Importance to six states instead of eight. The reasoning behind this proposal was that there had been consensus over the top six states of industrial significance. There remained considerable contention over the last two seats.Footnote 127 To counterbalance the effects of removing the status of Chief Industrial Importance to India and Canada, the Commission had also wanted to reserve 37.5% of the permanent government delegates and 25% of worker delegates to non-European states for rotating members on the Governing Body. The Indian delegate, Mr. Joshi resisted the Commission’s Report claiming that non-European states had neither asked for nor would approve of the Commission’s recommendations.Footnote 128 Canadian delegate Monsieur LaPointe warned francophone Belgium and French delegates that such a move would be a ‘radical alteration of the peace treaty’.Footnote 129 Meanwhile, Mr. Basu for India cautioned that removing India as a state of Chief Industrial Importance only a month after achieving this position would cause widespread indignation against the ‘West’ in India and the greater ‘East’.Footnote 130

Belgium’s delegate attacked India and Canada for acting in their national self-interest rather than attempting to ascertain a suitable composition for the Governing Body. He claimed that it was impossible to ascertain a true definition of ‘Chief Industrial Importance’ whilst arguing that Belgium should retain a seat on its proposed reduced permanent body of six Chief industrial states.Footnote 131 Canada responded that it was fully prepared to remove the permanent positions altogether and have a fully elected body rather than accept Belgium’s proposals. The Indian and Canadian delegations urgently appealed to Britain for support against the Commission’s proposals.Footnote 132 The British intervention rapidly swung the debate, arguing that the Body risked alienating India and Canada if they were jettisoned from their recent promotions. The Conference voted 62 to 8 to retain eight states of Chief Industrial Importance.Footnote 133 India’s position as a state of Chief Industrial Importance was secured, and it has remained as such to the present day.

Conclusion

The ILO’s attempt to define ‘industrial importance’ is today an almost forgotten episode in the history of international organizations. However, many of the themes that arose during India’s challenge of the definition of chief industrial importance, Eurocentricity, and the neutrality of international technical bodies remain challenges for contemporary international organizations.

International organizations such as the ILO changed how industrial importance was measured several times throughout the 1930s and 40s. Other metrics, including relative economic indicators, were finally replaced in 1983 by determining industrial importance on nominal Gross Domestic Product.Footnote 134 The aggregate economic indicators finally triumphed over relative ones at the ILO, despite new dissenting calls that GDP failed to adequately capture purchasing power and a host of other economic indicators.Footnote 135 Nonetheless, the ILO’s Governing Body holds a greater diversity of states than it did when using relative economic indicators.

At other organizations, however, the dichotomy between large, less developed economies and relatively more developed economies in the West has become an increasing political sore in ostensibly apolitical organizations. At the turn of the century, scholars warned of the reimposition of a ‘liberal, globalized civilization’ through international organizations and NGO’s. International law working through international institutions worked to harmonize the world with Western norms and markets ‘on a scale that dwarfs the 19th and early 20th century’ that constituted a new ‘Standard of Civilization’.Footnote 136 Not unlike the expansion of the League and its ancillary agencies a century earlier, the expansion of international governance following the end of the Cold War was again to be administered through technical and scientific international bodies. Meanwhile, granting dispensations to developing economies such as ‘Special and Differential Treatment’ played an important role in absorbing formerly more protectionist economies such as China and India into organizations such as the WTO.Footnote 137

Nonetheless, many of these organizations have not been able to avoid the intrinsically political nature of their work. Over the last three decades, the vast economic growth of some developing economies, such as India and China, is steadily closing the ‘Great Divergence’ of wealth between the West and Asia.Footnote 138 As development status is becoming a more salient demarcator in allocating responsibility in global affairs, many Western states, most notably the United States, have sought to end special and differential treatment for larger developing economies.Footnote 139 This has caused numerous problems for organizations such as the WTO, as new protectionist administrations politicize the work of technocratic organizations.Footnote 140 However, calls to shift from the current self-declaratory model of ‘developing’ status to a more statistical standard are unlikely to depoliticize the organization. Contrary to the case of India seeking the status of Chief Industrial Importance, the stigma attached to ‘developing’ status has changed and has effectively been utilized by developing states, many of which consider differential treatment a right.Footnote 141

The continued rise of large economies with relatively lower GDP per capita will increasingly pressure ‘developed’ states to abolish differential treatment or to reframe developing status in a way that excludes large but relatively less developed economies. Although this reaction began under a particularly protectionist administration under Donald Trump, there is no sign that the dichotomy between developing and developed and its use as a tool to determine international obligations will end soon.Footnote 142 Attempting to break this stalemate through a new statistical standard will likely be fraught with many of the same arguments and pitfalls witnessed in the ILO’s attempt to define industrial importance a century ago.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.