Despite an increasing focus on gender equity in the profession, substantial inequity remains. Previous studies (Gumpertz et al. Reference Gumpertz, Durodoye, Griffith, Wilson and Rosenbloom2017; Kaminski and Geisler Reference Kaminski and Geisler2012) analyzed the “leaky pipeline” that results in the underrepresentation of women—as well as those with transgender, nonbinary, and other gender identities—in academic and tenured positions (Box-Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box-Steffensmeier, Cunha, Varbanov, Hoh, Knisley, Holmes and Larivière2015; Wolfinger, Mason, and Goulden Reference Wolfinger, Mason and Goulden2008). Extant work suggests multiple possible causes, including family commitments (Box-Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box-Steffensmeier, Cunha, Varbanov, Hoh, Knisley, Holmes and Larivière2015; Suitor, Mecom, and Feld Reference Suitor, Mecom and Feld2001) and disproportionate participation in “service activities,” such as graduate-student mentoring (Rosser et al. Reference Rosser, Domingo, Pasion, Gerber, Harris, Mamo and Rebanal2016).

This article focuses on a different cause, one that can arise even when all parties are well intentioned: non-inclusive professional networks. Professional networks pass along information and recommendations that drive personnel decisions (e.g., hiring), acceptance into graduate programs or selective conferences and workshops, and the granting of awards. According to the literature on “workplace ostracism,” defined as “being ignored and excluded by others on the job,” exclusionary professional networks are a barrier to gender and racial equality in academia (Zimmerman, Carter-Sowell, and Xu Reference Zimmerman, Carter-Sowell and Xu2016). This mirrors what we know about the effects of the composition of networks on individual and mass behavior (Larson and Lewis Reference Larson and Lewis2017; Siegel Reference Siegel2013; Sinclair Reference Sinclair2012): If network structure makes it sufficiently difficult to pass along information to important actors, as it does if networks are exclusionary, then that information is all but absent in decision making, and unrepresented individuals find their ability to influence professional outcomes vastly diminished.

An inclusive network is one in which an individual’s professional networks are diverse. Given the spotlight’s theme, we focus on gender diversity; however, the online appendix includes suggestive support for the relevance of our argument to racial diversity. Non-inclusive networks are those in which an individual’s professional networks are not diverse. Non-inclusivity or outright exclusion could be enforced by the dominant identity group, perhaps as backlash against rising diversity in the workplace (Zimmerman, Carter-Sowell, and Xu Reference Zimmerman, Carter-Sowell and Xu2016). It could be exacerbated by feedback, in that those with underrepresented identities may react to exclusionary environments by withdrawing further from networks that insufficiently include them (Johnston Reference Johnston2019). It also could be a result of homophily: the tendency to form connections with those who possess similar characteristics. Homophily can arise due to bias or to a lack of demographic diversity among those with whom we might make connections (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001).

Regardless of the cause of the non-inclusivity—and building on work that analyzes network-produced inequity in academia (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Horiuchi, Htun and Samuels2020)—we argue that professional networks that fail to include individuals with underrepresented gender identities can exacerbate gender bias and inhibit career advancement in political science. Furthermore, because networks operate regardless of intent, we posit that considering the role of professional networks can shed new light on the noted sluggishness of progress in increasing gender diversity in academia (Box-Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box-Steffensmeier, Cunha, Varbanov, Hoh, Knisley, Holmes and Larivière2015).

…we argue that professional networks that fail to include individuals with underrepresented gender identities can exacerbate gender bias and inhibit career advancement in political science.

To obtain a basic sense for how non-inclusive networks regarding gender identity might animate personnel decisions, we surveyed US political scientists in March 2020 (Datta and Siegel Reference Datta and Siegel2021). Our main independent variable of interest was respondents’ answer to the question of “whether they identify with an underrepresented gender identity, relative to the whole of political science.” We used this question format in order to be inclusive of different underrepresented gender identities. The online appendix contains a full description of the survey, its analysis, and a link to the (anonymous) data. Here, to avoid overly strong claims, we merely highlight a pattern of responses generally supportive of the view that the problem of non-inclusive networks that we and other scholars have identified is a serious one.

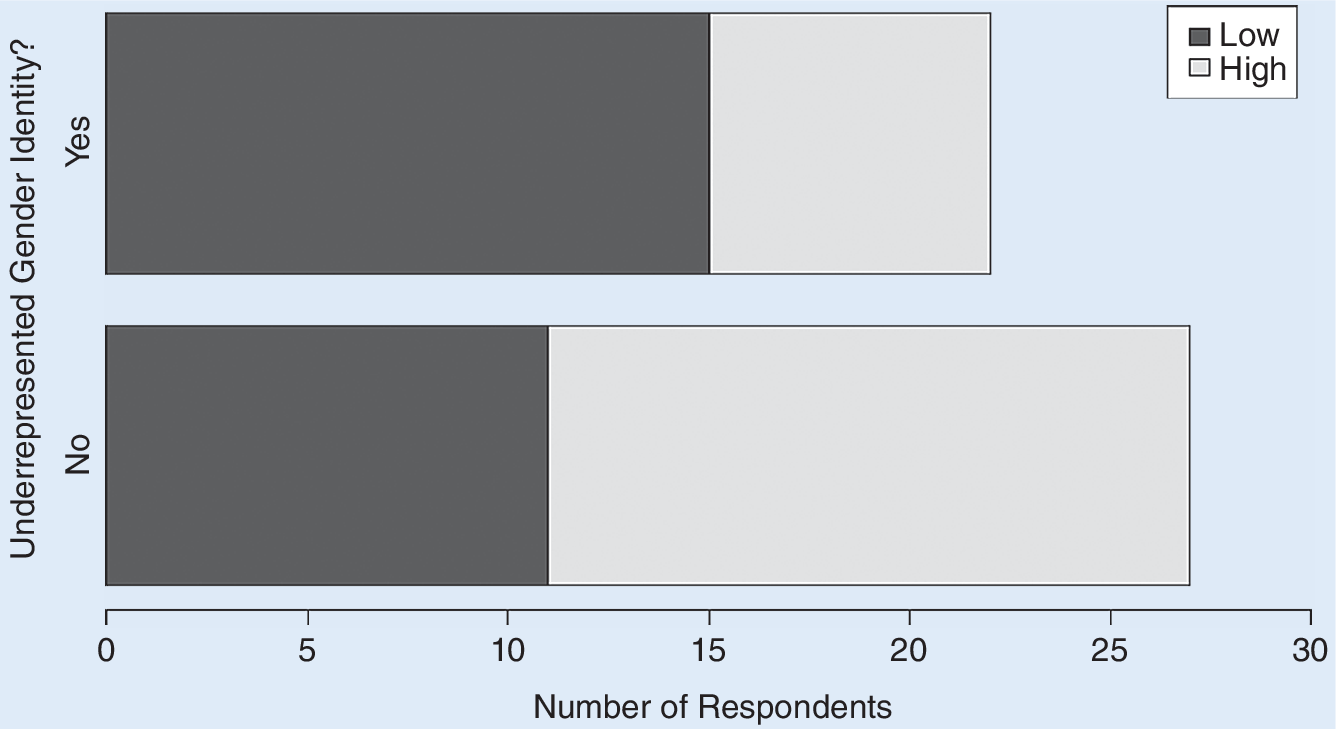

More than twice as many survey respondents of all genders were more likely to become aware of professional opportunities and contacts in informal settings. However, we found suggestive evidence (not quite significant at the p<0.1 level) that those faculty members with underrepresented gender identities may attend these events less often (figure 1).

Figure 1 Faculty with Underrepresented Gender Identities May Attend Fewer Social Activities

What proportion of these social activities (with faculty and/or graduate students) would you say you attend each month? (Faculty only).

Less attendance was not present among graduate-student respondents, which may be the result of higher demands on faculty respondents’ time or from their not feeling as included. Several questions in the online appendix address the latter possibility. Regardless, faculty with underrepresented gender identities may be less likely to participate in the types of informal networking that most people find to be most helpful. Coupled with evidence (see the online appendix) of the presence of demographic homophily in personnel-decision networks, our results suggest that professional networks are important but may underserve those with underrepresented gender identities. Responses to our optional free-response question by individuals with underrepresented gender identities echoed that assessment, as follows:

Biggest problem in my department are “informal” happy hours with the chair or other influential member where that individual dispenses information and/or opportunities to his favored junior colleagues. Also, a culture of gossip about members of faculty (always women) who do not participate in these events—we are considered “not as invested” in the department and “likely to leave.” (Respondent 55)

Especially at conferences, one can be in mixed gender groups and both men and women often look or speak toward the men in the group. I try really hard to participate and make sure that I look at and include women, especially younger women, in the conversation. (Respondent 94)

What can be done? Building on other proposed solutions that highlight the importance of reshaping norms and behavior among all political scientists (Htun Reference Htun2019), we offer some suggestions. Because an individual’s network is likely non-inclusive, those in a position to be a recommender or to make personnel decisions should look beyond their immediate networks in making recommendations. At minimum, network-derived information should be discounted relative to what is available from more objective sources.

It would be better to increase the frequency of inclusive networks. At the individual level, this entails a deliberate effort to broaden one’s reach. At the group level, professional associations could publicize the identities of diverse groups of scholars with varied expertise, amplifying the work of groups such as Women Also Know Stuff and People of Color Also Know Stuff; host networking events to bring diverse scholars together; and aim to diversify conference participation.

At the structural level, we should think more carefully about the spaces in which social interactions operate. Happy hours and later trips to the bar best serve those who are relatively free from family obligations and are well networked. They also can put those with underrepresented gender identities in an uncomfortable or even dangerous position. They thus do little to broaden networks and much to reinforce existing non-inclusive networks. Instead, activities that take place in the office during business hours, such as group lunches or family-friendly activities at other times, may encourage broader participation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Leann Mclaren and Trent Ollerenshaw for their assistance with this article; to Mala Htun, Alvin Tillery, Jr., Betsy Super, and all of the participants at the 2018 APSA Diversity and Inclusion Hackathon for spurring an important conversation; and to Dan Mallinson and Rebecca Gill for all of their work in putting together this spotlight.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TQYV0I.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S104909652100007X.