Nothing frightens the liberal imagination like the specter of fascism. This fear is reasonable, since fascism represents modern history’s most apocalyptically violent political ideology and disdains the liberal values of equality and democracy. One quality liberalism shares with fascism, however, is the inability to distinguish between ethics and aesthetics. Or, more specifically, an inability to grapple with aesthetics that oppose liberalism’s ethics. Take for example retired New York Times theatre critic (1993–2020) Ben Brantley’s statement: “I can’t condemn wholesale any genre — I mean, unless it’s Nazi art, you know” (in Weinert-Kendt Reference Weinert-Kendt2021). Brantley’s quote comes from an interview titled after his philosophy of reviewing: “A Critic Is a Mirror, not a Shaper.” Brantley explains that his career was not about shaping public opinion, unless it’s on the subject of “Nazi art,” you know? Brantley is not alone in his certainty. Take art critic Sarah Rose Sharp’s review of Steven Heller’s The Swastika and Symbols of Hate (2019), which traces the history of the titular ideogram. Be not concerned that Sharp said she did not finish reading the book; doing so was unnecessary because, “If you believe in art and the power of symbols, as I do, there is a sense that they gain power in repetition — that is the lifeblood of propaganda. […] A symbol can only lose meaning through obscurity, not through scrutiny; it cannot be intellectualized away” (Sharp Reference Sharp2020). Fascist aesthetics not only invite uncritical assessment, but self-assured dismissal. The aesthetics of fascism are shunned because to contemplate them is to celebrate them, that is if you believe in art as these critics do, you know? What we are expected to “know” or “believe” is that when it comes to fascism, aesthetics and politics are inseparably linked. This is the great aesthetic lesson liberalism drew from fascism, confirming a naïve belief that politics can be distilled to costumes; you don’t even need to finish the book to find out.

Figure 1. Jonathan Meese (in mask) and Lilith Stangenberg. Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. Theater Dortmund, February 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer)

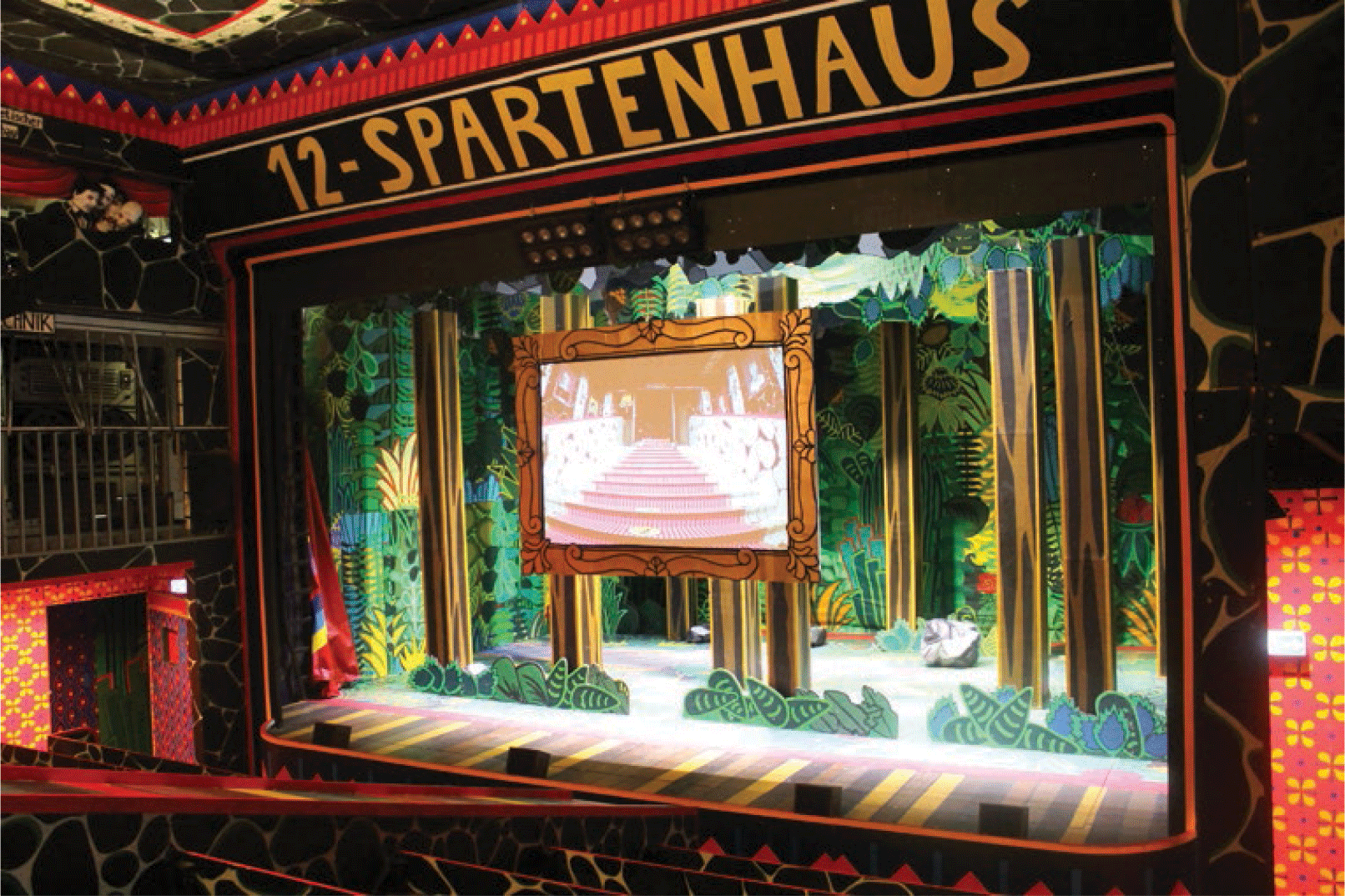

An updated book on fascist aesthetics would feature Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller’s massive Nazi-style Parteiadler (party eagle) painted in cartoonish red and black above the administrative offices of the duo’s fictitious theatre institution-cum-performance installation, 12-Spartenhaus (2013). It is the fifth production in Vinge/Müller’s ongoing Ibsen-Saga (2006–) that imagines Henrik Ibsen’s works in the duo’s signature cartoon designs, grotesque masks, extreme violence, and durational performances. The entrance to the installation was overseen by a swastika-wearing accountant ringing a cash till; more chilling than the Nazi imagery is 12-Spartenhaus’s naturalization of violence in the service of an uncompromising artistic vision. The Parteiadler-adorned halls are bathed in stage blood when the production’s director — Vinge — executes the institution’s administrators in a revenge fantasy based on the real conflicts between Vinge/Müller and the actual administrators of the show’s producing theatre, the Volksbühne-im-Prater. Sporting a Richard Wagner T-shirt and a rubber mask coated in real shit, Vinge “fires” a hail of bullets from a cardboard AK-47 at the theatre’s “employees” — characters whose respective jobs are written on name tags. Vinge showers his victims with blood from plastic squeeze bottles, then drags the viscera-slick body of the theatre’s fictitious managing director through the halls and splays the corpse across the entrance to the company’s replica Weimar theatre: a grim warning to all who oppose the Ibsen-Saga’s totalizing vision.

While Vinge/Müller imbue their performances with the ideological fanaticism of fascism, Jonathan Meese embodies fascist tropes to claim art as a rarified state. At the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Meese stands at a microphone-laden podium atop a wooden platform flanked by rows of Ionic columns. Dressed in a tracksuit and sunglasses, Meese commandeers the institution that famously rejected Adolph Hitler’s art school application. He launches into an impassioned lecture-performance titled Totale Graphik (2012), a self-described “propaganda speech” professing the primacy of art and our role as its servant in the coming “Dictatorship of Art.” Meese stretches his words into polemical song, punctuating his decrees with Germany’s most haunted adjective — “total” — evoking both Richard Wagner’s Gesamkunstwerk (total artwork) and Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels’s call for Totalen Krieg (total war). Meese ends the 70-minute oratory with a flurry of Hitler salutes. “There is nothing wrong with it,” he asserts, “to be ideological is evil, but to make a gesture is cool” (Meese Reference Meese2012). The audience applauds.

Occupying the contested space between fascist gesture and ideology, Vinge/Müller and Meese established themselves as two of Germany’s most important and polarizing artists of the past decade. Their unironic performances of fascism’s fanatical commitment to art have resulted in criminal charges, smear campaigns, and boycotts, while securing them prestigious awards, funding, and recognition by the Berlin Theatertreffen. Footnote 1 Combining fascist imagery with a militant aestheticism personified in the autocratic, male leaders of their respective projects — Meese and Vinge — these artists break from Germany’s reunification-era theatre that exposed entanglements of art and ideology through parody and deconstruction. Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s art meanwhile reveals what we get wrong about fascist aesthetics: the politics of fascism and the aesthetic formations that promote it are not inextricably linked. Instead, these artists rethink the problem of aesthetics and ideology by recovering fascist impulses to establish the autonomy of art.

Figure 2. Interior mainstage of the 12-Spartenhaus building. 12-Spartenhaus by Vinge/Müller. Volksbühne-im-Prater, Berlin, Germany, June 2013. (Photo by Angela Roudaut)

Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s performances are equally instructive for understanding why German theatre has not had the luxury of dismissing fascist aesthetics. Germany has produced the most lethal form of fascism and the nation’s theatres have historically used aesthetics to reflect on ideology. German theatre has long been distinguished from US theatre because of its prominence in public life, political debate, and national identity. German theatre grapples with fascism not only as a matter of civic duty but also because it understands, as Jean Genet purportedly claimed, that “Fascism is theatre” (in Sontag [Reference Sontag1975] 2002:103). As “the most self-consciously visual of all political forms,” according to Robert Paxton, fascism “presents itself to us in vivid primary images: a chauvinist demagogue haranguing an ecstatic crowd; disciplined ranks of marching youths; colored-shirted militants beating up members of some demonized minority; surprise invasions at dawn; and fit soldiers parading through a captured city” (Paxton Reference Paxton2004:9). More than spectacular, Paxton’s examples are all tellingly embodied. What Paxton calls “visual” is better understood as theatre: its force relies on the copresence of performers and an audience to realize Western theatre’s awful power to enrapture and transform a community.

The utility of performance for fascism was its purposed veracity. As Kimberly Jannarone explains, “theatre performances were conceived as ‘real’ events that affected the spectator not as art but as truth, an essential step toward the necessary revolution” (2009:199). Deployed as reality, theatre inspired a sensation of truth by concretizing the abstractions of fascism’s ideology while incarnating a body politic that imagined its rebirth depended upon expelling its alleged enemies. Footnote 2 The overlap between fascism and art comes from what Ulrich Schmid calls fascism’s “ontological aspirations […] to replace reality with its own demiurgic project. Reality was not accepted as a given fact, but as a deficient material which had to be modelled and turned into beauty. Fascist art does not want to depict or represent reality — it creates reality” (2005:133). What fascism’s desire to create reality produced, however, were parasitic aesthetics to support its civic, political religion (see Berghaus 1996; Mosse Reference Mosse1996; London 2001; Strobl Reference Strobl2007). A distinction must therefore be made between what a fascist aesthetic achieves in the political realm and the demiurgic energies from which it springs. Evidenced by Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s work, those creative impulses continue to allure because they, as Susan Sontag describes, speak to “the ideal of life as art, the cult of beauty, the fetishism of courage, the dissolution of alienation in ecstatic feelings of community; the repudiation of the intellect; the family of man (under the parenthood of leaders)” ([1975] 2002:96). The draw of fascist aesthetics cannot be extinguished by the barbarities of National Socialism or subsequent fascist variants because those artistic ideals precede their use by fascists.

Figure 3. Jonathan Meese and Lilith Stangenberg in Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. Theater Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany, February, 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer)

What then are we to make of artists like Meese and Vinge/Müller who claim to channel fascism’s demiurgical drive into art before it reaches the realm of political action; who insist the theatre is a space where reality is not depicted, but created? While the same might be said of much theatre, these artists’ fascistic tendencies are clearest in their representations of reality as ideologically and materially deficient. Reality, for Vinge/Müller and Meese, is not a rejected style rooted in realism, theatre of the real, or the materiality of the body that is integral to performance art. The reality these artists shun is the inaesthetic, the rule-bound, the bureaucratic, and the cynical. Reality is unmagical, the enemy of art. In reality’s place, Vinge/Müller and Meese propose an idealistic art as the ultimate means of transforming the world.

What is in question here is not fascist doctrine, which is as reproducible in a pamphlet as it is onstage, but the fascist effect: the enthralling promise of rebirth through an aesthetic helmed by an uncompromising leader. Incorporating the indefensible ideologies and the images of fascism into their work, Meese and Vinge/Müller mark the theatre as an escape from reality, an autonomous space of and for the world as art. Despite dismissive critics like Brantley and the persistence of neofascist violence and policy, fascist aesthetics must be taken seriously because performance is endemic to fascism. The critic who ignores fascist aesthetics cannot understand contemporary performance.

Jonathan Meese and the Dictatorship of Art

Since the late 1980s, Meese has incorporated fascist imagery in his art. He is a multidisciplinary artist whose sculptures, manifestoes, installations, YouTube videos, paintings, and performances repurpose mythology, history, and popular culture as crude iconography. Across mediums he creates caldrons of vibrant color, grotesque figures, collages of magazine cutouts, and block-letter idioms scrawled in thick globs of paint. Recurring content is drawn from German history, including portraits and quotes from Wagner, Hitler, and Heidegger, as well as iron crosses, spiked helmets, and swastikas; and from popular culture, such as John Wayne, Anna Wintour, Scarlett Johansson, and James Bond characters. Most prominent within Meese’s work is the artist himself, whose slacker-demagogue visage, name, and slogans crown nearly all his works. The result, Ross Simonini describes, is an “energetic maelstrom that is both brutal and chromatically stunning” (2018).

Meese’s works build upon the Die Neuen Wilden (The New Fauves, literally “wild ones”), who in the late 1970s broke from Conceptual and Minimalist art by turning to the edgy ethos of punk and new wave music. Albert Oehlen’s series of Bad Paintings, featuring a controversial portrait of Adolph Hitler (1986), typified the New Fauves’ attack on good taste. Nazi imagery served as countercultural provocation throughout Europe, most notably by British Punk bands like the Sex Pistols and Siouxsie and the Banshees who brandished swastika armbands. What punks used to antagonize self-satisfied pieties in Allied countries were criminal acts in Germany, which was and remains hypersensitive to Nazism. Since 1952, §86a of the German criminal code outlaws the “use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations.” Punishable by up to three years imprisonment, the legislation specifically bans the swastika and Hitler salute. Allowances are made, however, for “art or science, research or teaching” (see Stegbauer Reference Stegbauer2007). In the protected category of art, fascist imagery marks a limit, signposting the deepest, darkest, most shark-infested waters where morality dare not swim.

Figure 4. Lilith Stangenberg and Jonathan Meese in front of Meese’s collage of political figures: Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler, among others. Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. Theater Dortmund, Germany, February 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer).

Meese builds on his predecessors’ transgressions, but deploys fascist imagery to different ends. The artist’s aims are most evident in his theatre and lectures, which focus on the ideological function of performance. Meese’s live shows transform the artist’s interdisciplinary expressions into nonnarrative collages of action that are at once shambolic and ceremonial. De Frau (Dr. Poundaddylein-Dr. Ezodysseusszeusuzur) (2007), the first work Meese wrote and directed for theatre, litters the Volksbühne’s mainstage with the characters, images, and energies previously displayed on his canvases. The cast of seven performs improvised disjointed actions while quick-changing between characters in a demonstration of creative freedom, guided by Meese’s onstage, shamanistic presence. The elaborate dress-up unfolds before Meese’s canvases and a castle-like structure spins on a turntable in front of a massive black-and-white video of the director. The designs are less location than invocation: their eclecticism echoing the impulsive freedom enjoyed by the performers. As Meese explains, in performance, “I want things to overstretch themselves. I want things to take control — not me and my opinion or my taste” (Meese Reference Meese2007). Footnote 3 The stage allows Meese and his collaborators to play out creative license, to embody art’s boundlessness in shared space and real time.

Figure 5. Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. The cast gathers in front of Meese’s painting of a Moomin-like character. From left: Maximilian Brauer, Bernhard Schütz, Lilith Stangenberg, Jonathan Meese, and (downstage) Uwe Schmieder. Theater Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany, February 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer)

Since Meese’s inaugural stage production, his work has increasingly incorporated fascist iconography. In Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! (Lolita [R]evolution [reputation-damaging] — All of you are the Lolita of yourselves!, 2020), Meese and a cast of five other “Lolitas” spend the three-hour runtime alternating among the characters of Vladimir Nabokov’s famed novel. Rather than dramatize the book’s conflicts or story, Lolita takes the novel as a point of reference for instinct and desire, which, for Meese, is synonymous with creativity. Imbued with the spirit of Lolita, the ensemble cycles through impulsive acts. They play ping-pong, sing out of tune, cuddle stuffed animals, dance about, and jump on a mattress between costume changes into babies, medieval crusaders, a hotdog, Darth Vader, Sumo wrestlers, and Nazis, all with the discordant flair of attention-hungry kids putting on a show. Fifteen minutes into the production, Meese and castmate Lilith Stangenberg don Nazi uniforms and sing the word “Germany” in increasingly inventive phrasing over canned techno. Meese, draped in a green rubber mask and oversized baby bonnet, proffers a Hitler salute throughout, while Stangenberg scoots around the stage on a rolling German shepherd stuffed animal. The remaining four performers bang pots, play with mannequins, and ride on the two swings hanging on either side of the stage. It is grating, puerile, funny, and free.

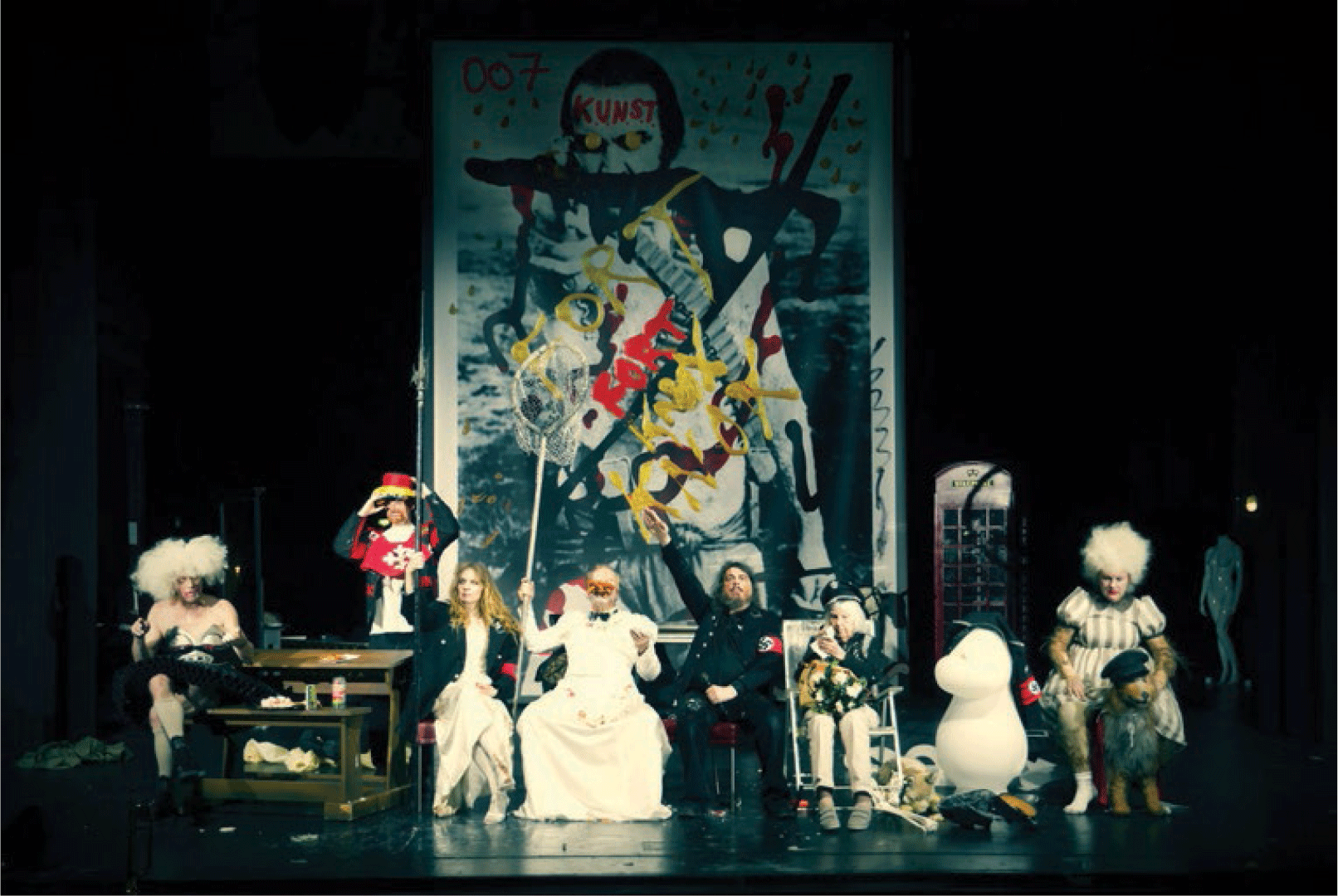

Figure 6. From left: Uwe Schmieder, Maximilian Brauer, Lilith Stangenberg, Bernhard Schütz, Jonathan Meese, Brigitte Renate Meese (Meese’s mother), and Anke Zillich in front of Meese’s painting of Sean Connery in the film Zardoz (1974). Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. Theater Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany, February 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer)

Shortlisted for the 2021 Theatertreffen, Lolita was celebrated as “[a]n infinitely liberating ritual, in the course of which the ensemble has transformed itself into crusaders of art” (Westphal Reference Westphal2021). The spirit of liberty afforded the cast was extended to the audience, with the theatre doors left open so patrons could come and go for beer or escape. Meese’s Hitler salute continues for nearly the whole performance as he sermonizes on Germany, art, and Lolita before massive reproductions of his paintings featuring the Führer, Stalin, Mussolini, Caligula, Dr. No, and the Swedish cartoon character, Moomin. In the waning moments of the show, Meese brings his mother — Brigitte Renate Meese — onstage to “Sonne” (Sun, 2001) by the German hard-rock band Rammstein, a group similarly accused of producing neofascist art. Brigitte, who often appears in her son’s art, is seated in a downstage lineup of the show’s disheveled characters: a Lolita with a butterfly net, a pig-masked SS solider, and Meese, who sings along to the song while slinging himself back-and-forth in a rocking chair brandishing a fully extended Hitler salute. Brigitte wearily tries to lower her son’s arm in what appears to be an act of genuine discomfort, while Meese mechanically raises his arm as if driven by a spirit. In the concluding image, the cast sits around a table on which a four-foot replica of the hippo-like Moomin figure is centered. The Lolitas are now mostly dressed as Nazis, including Brigitte, who is given a swastika armband and SS cap. Behind them, a massive image of a bare-chested Sean Connery pointing a revolver looms over the scene. Taken from the film Zardoz (1974), Meese has blacked-out Connery’s eyes and scrawled KUNST (ART) across the figure’s forehead. Below, the cast extend their arms towards the Moomin in a gesture somewhere between spirit fingers and a Hitler salute as the curtain slowly descends. While the seeming irrationality of Meese’s productions may irritate audiences, his use of fascist imagery has long garnered critical and legal ire. As journalist Georg Diez notes, “it doesn’t look like Meese wants to dispel Hitler; it seems more like an invocation” (Diez Reference Diez2007). The argument cuts to the core of the issue — as Brantley’s and Sharp’s arguments suggest — that to play with such material keeps it in circulation, forestalling its disappearance. Theirs is a simple choice: one can condemn fascist aesthetics (by expunging them from the repertoire) or promote their implicit ideology. What Meese suggests is an alternative.

Meese employs fascist imagery to promote the “Dictatorship of Art.” His vision for this dictatorship is straightforward: “Art rules the world, and art is the leader of the world, not just in this country, […;] art destroys and finishes all political systems” (2013). For Meese, art is antithetical to ideology. The incompatibility stems from his belief that art is instinctual, even biological, rather than intellectual — what Meese describes as “metabolistic.” Audiences, not images, are the harbingers of ideology, projecting political meanings onto art. The Dictatorship of Art restores images and gestures to pure form because art establishes its own autonomous zone: “If you put the Hitler salute onstage then you are playing with it and neutralizing [it]; then you put it onstage in another reality, not into reality. You put it out of reality — that is the only thing you can do. Only art can deal with the past” (2013). The past is Meese’s proof of art’s superiority. He cites the preserved ruins and relics of bygone cultures as a testament to art’s power, while ancient political systems, religions, and beliefs disappear. On these grounds, art can scrub fascist symbols and choreography clean of ideology. Art’s strength is its inconsequence, as there are no real casualties within art, where everything is fiction. Reality, the realm of ideology, is responsible for suffering; “reality,” Meese tells us, “is shit” (2013).

I can imagine readers of TDR rolling their eyes at such a notion because since the 1970s it has been the project of theatre and performance studies to illustrate the inescapable coexistence of art and ideology, to parse the human forces that give rise and meaning to art forms, to situate them historically and frame them theoretically, to purge the notion of artistic autonomy in an effort to reveal theatre and performance’s centrality to society. I’m less concerned with the feasibility of Meese’s project than the imaginative space it opens up, which, of course, is the primary impact theatre can hope to have on the world.

Meese’s performances realize the Dictatorship of Art by creating spaces in which art might rule. Meese treats the theatre — or any space where he performs — as antithetical to ideology. To demonstrate this, he selects the most resistant of forms, Nazi detritus, to test the possibility of divorcing ideology and image. The aim is not to recuperate the swastika or Hitler salute, but to establish art as a space in which any form can be repurposed. Following this logic, if art neutralizes the ideology of Nazi iconography, art can reorder the world and art’s transformative supremacy will triumph. What is provocative in Meese’s work is not that he displays Nazi artifacts, but that he does so while taking seriously the world-building promise of fascist aesthetics.

Meese’s work uncannily realizes his philosophy of art. While participating in an event titled “Megalomania in the Art World” (2013) at Kassel University, Meese performed the Hitler salute. Charges were brought against Meese because the context of a panel discussion was allegedly journalistic, not artistic. Meese’s lawyer, Pascal Decker, explains that when defining art under German law, “no formal criteria are set […;] one answers the question [of what is art] from the respective context” (Decker Reference Decker2013). Meese was acquitted under the provision that the gesture was made within the context of art. The ruling verified a legal distinction between reality and art, which is Meese’s entire point. As Decker argues, “Why shouldn’t an artist be allowed to transform an interview into a performance? […O]ne quickly comes to the conclusion that the artist Jonathan Meese is on the podium. And not the private person” (Decker Reference Decker2013). Yet Meese’s work deliberately blurs the distinction between what he calls the “stage person Jonathan Meese and the puny private person” (in Knöfel and Wellershoff Reference Knöfel and Wellershoff2013). The artist’s ability to alter a context from ordinary to art has been well established at least since Marcel Duchamp submitted his readymade Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists in 1917. What complicates the issue in Meese’s case is that he presents himself as the site of transformation. In doing so, Meese not only adopts fascist iconography in service of a “dictatorship” of art, but also embodies the most famous of all fascist tropes: the autocratic persona.

All definitions of fascism feature the centrality of a charismatic leader. Roger Griffin calls this figure the “propheta,” the typically masculine mouthpiece for and embodiment of fascist ideals (2007:14). For historians like Eric Michaud, the Third Reich is distinguished by the Führer’s role as an “artist-dictator,” in which leadership is equated with creativity. Michaud points out that “Hitler had managed to transpose to the political sphere his artist’s conviction that ‘art is a sublime mission that demands fanaticism’” (2004:5). Art’s sublimity, conjured through fanatical devotion, imbues fascist aesthetics with the promise of transcendence. Or as Michaud summarizes: “What National Socialism sought to highlight in both of its models, art and Christianity, was a process that was able to lead from idea to form” (xiii). Devotion was measured through the racialized, heroic body, with the artist embodying that heroism. “The heroic,” for Boris Groys, “was nothing other than a willingness to live for eternal fame and to exist in eternity. The heroic act was defined by its transcendence of immediate, temporal goals and was an eternal role model for all time to come” (2013:133). This led to fascism’s genocidal destruction as well as its fetish for creation. Fascism, therefore, can be understood as ideology embodied, a fanatical corporeality, or as Groys suggests, “[f]ascism introduced the age of the body, and we continue to live in that age, even though Fascism as a political program has been displaced from the cultural mainstream” (131). As embodied arts, performance and theatre are ideal mediums for presenting the propheta as a distillation of fascist aesthetics.

Just as self-fashioned politicians did not begin with Hitler and Mussolini, Meese’s propheta persona has ample precedent. Footnote 4 Beneath his costumes, Meese always wears a uniform of a black Adidas tracksuit; dark, shoulder-length hair, unkempt beard, and Ray-Ban sunglasses. Despite his declarations on behalf of the dictatorship of art, he occasionally performs drunk and conducts his works haphazardly without a clear script. He is, as Matt Saunders describes, “neither shaman nor actor. He is clumsy” (2005:95). This ineptitude is largely good-humored even when Meese is smashing things or goose-stepping. Meese chats up and laughs with audiences, performs alongside his mother, is effusive in interviews, and gives military salutes to audiences as if he were their personal, chilled-out foot soldier of art. Claire Bishop describes Meese’s mixture of incendiary images and shambolic behavior as a “Teutonic abjection,” at once powerful and hollow. “While purporting to be about Germany’s repressed history,” Bishop continues, “Jonathan Meese’s work seems more about Jonathan Meese” (2006). He is undoubtedly the central figure of his art, which is littered with self-portraits, scrawled signatures, and the artist’s bodily presence in the gallery and onstage. But Meese’s participation is framed as a sacrificial devotion to art: “I must do my duty to art!” Meese declares, “The dictatorship of art is not the dictatorship of an artist” (2013). Meese may speak with the charismatic authority of the propheta, but he casts himself as a devotee, not a leader: “I don’t want followers. I refuse discipleship” (in Knöfel and Wellershoff Reference Knöfel and Wellershoff2013). Despite Meese shrugging off his power, his self-aggrandizement through art is the performance of Germany’s repressed history. As Michaud and Groys illustrate, the self-sacrificing artist-hero is, perhaps, the most influential and consequential figure of German history: the artist-dictator whose creative vision can dispel reality and remake the world.

Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller’s Radical Fiction

Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller take up a similarly improbable effort to reimagine the world as art. Beginning in 2006, Norwegian-born Vinge and German-born Müller began a series of interconnected performances based on the plays of Henrik Ibsen called the Ibsen-Saga. Vinge (director/performer) and Müller (scenographer/performer) earned an international reputation for their singular aesthetics, which I’ve described as total radical fiction (see Friedman Reference Friedman2012). Each of their eight Ibsen-inspired productions recreates the minutiae of material reality as arch artificiality. Their representational sets, props, and costumes are handmade and hand-painted in vibrant colors and detailed patterns that announce their fictitiousness. Much of the set is constructed from cardboard, giving their scenography the flimsy two-dimensionality of a toy theatre. All performers appear in grotesque rubber masks and wigs, and move like animatronic dolls with stylized gestures, miming to individualized, recorded dialogue. As if inside a video game, every object, gesture, and behavior is accompanied by exaggerated, hyperrealistic sound effects: characters have unique footsteps and voices, doors slam, faucets run, and lights hum. Ibsen’s works are the pretexts for Vinge/Müller’s associative dramaturgy that explores the plays’ themes and characters through an ever-expanding universe of references, including Hollywood blockbusters, classics of the operatic and dramatic canons, historical figures, and sports heroes. Footnote 5 These associative narratives expand Ibsen’s central dramatic conflict: the tragedy of the creative individual’s efforts to break free from a staid society and realize themselves.

More than a story for dramatic representation, the struggle of creativity against reality is enacted through the Ibsen-Saga’s productions. Each performance is singular and open-ended, lasting anywhere from two continuous weeks without intermission, to ending unexpectedly after only 45 minutes. The performers and audiences come and go throughout the shows to satisfy the need for the bathroom, food, and sleep. On average, performances occur two to three times a week lasting 12 hours each, but the content changes between every performance in response to audiences and the artists’ impulses. The shows are directed in real time by Vinge, who, dressed like one of the stage creations, guides the action from the stage, auditorium, and sound booth by barking orders or interceding in the action. His is the ultimate authority in performance, a variant of the dictator-artist, the propheta as Ibsenian megalomaniac on a mission to remake the world as fiction. More than demonstrating theatre’s liveness, the singularity of each show expresses the Ibsenian desire to abandon the limits of reality and fully express oneself. Vinge/Müller’s art is tested against the limits of reality, limits that are measured by the endurance of the performers and audience as well as the tolerance of producers, unions, and technicians. Critic Doris Meierhenrich summarizes Vinge’s ambition: “he wants to subject life to his theatre of excess, to force it to another reality. This practical conflict is at the heart of the radical aesthetics and is in fact the oldest dream of the artist” (Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2011). Vinge/Müller use Ibsen precisely because the Saga’s aspirations are not new, but affirm the old dream of a fascistic art with the weight of Ibsen’s canon.

Fascist ideology snakes its way through the Saga in allusions to concentration camps, Joseph Goebbels’s speeches, swastikas, and the sadomasochistic exploration of the body’s limits. Unlike Meese, Vinge/Müller are more interested in the heroic ethos of fascist aesthetics than its specific iconography. The Saga’s intertexts reference fanatically driven artists (Richard Wagner, Albert Speer, Jackson Pollock, Maria Callas, Stanley Kubrick) in addition to Ibsen’s megalomaniacal characters. The dramatization of the Saga’s ambitions is an extension of fanatical commitment to the sublime mission of art. Vinge/Müller describe the Saga as a 500-year project, which, like fascism, can only be judged by the future. Müller explains: “The piece directs everything, what we have in our minds will direct and guide everything. The art stands above everything” (Müller Reference Müller2010). Like Meese, Vinge/Müller pledge themselves to art as a guiding force absolving them of ethical considerations. This was a central, deadly doctrine of fascism. “If aesthetic experience alone justifies life,” Jeffrey Herf reminds us, “morality is suspended and desire has no limits” (1986:12).

With art as their guide, Vinge/Müller transgress limits, resulting in boycotts, cancellations, and conflicts between the artists and the institutions that present and fund their projects. These conflicts often arise due to the artists’ refusal to adhere to time limits imposed on the work by producers and unions. Footnote 6 The unpredictable performances are compounded by the demands made of the performers who subject themselves to feats of endurance, dangerous stunts, acts of real violence, and excreta. Even in the context of the Saga’s limit-testing works, Vinge/Müller’s 12-Spartenhaus (2013) is an outlier. The final production of Vinge/Müller’s five-year residency at Berlin’s Volksbühne Prater Theatre, 12-Spartenhaus raised ethical questions about the limits of fiction by allegedly endangering audiences and theatre staff. The Volksbühne’s legacy of supporting provocative artists, including Meese, made it a natural home for Vinge/Müller. The duo’s aesthetic, moreover, is shaped by the theatre’s productions of the reunification era (see Vinge and Müller Reference Vinge, Müller and Friedman2016). Elements of Frank Castorf’s intertextual mash-ups, Christoph Schlingensief’s directorial theatrics, and Bert Neumann’s environmental scenography are key references for the Saga’s aesthetics. Despite their affinity with the Volksbühne’s style, Vinge/Müller’s extreme pursuit of artistic license set them on a collision course with the institution.

In translation, 12-Spartenhaus means “12-Division House,” playing on the categorization of art institutions by the number of genres they produce (a three-genre house would include opera, dance, and theatre). Here the title suggests the Saga’s extraordinary expansiveness. The production continues Vinge/Müller’s practice of thematizing conflicts between artistic ambition and the limits of reality. Rather than locate those conflicts within Ibsen’s domestic sphere — as was the case with previous works — the production was set within the theatrical institution itself: a fictional Nazi-era theatre. Much of the show’s action follows the daily operations of 12-Spartenhaus’s performers and administrators. The fictional theatre’s employees wear gestapo-style costuming, while the finance officer sports a swastika armband. The main hall of the theatre is adorned with a massive Nazi-style eagle, while scenes take place inside “Salon Kitty,” the name of an actual brothel used by Nazis during WWII. The conflation of Nazis and theatre administrators disparaged the Volksbühne’s staff, and impugned the theatre for the time limits and financial constraints it imposed on Vinge/Müller’s previous production, John Gabriel Borkman (2011).

12-Spartenhaus’s events and characters are based on Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1882), relocating the Stockmann brothers’ ideological standoff over the town’s contaminated water supply to the Nazi-era theatre. Standing in for the play’s polluted baths, an endless supply of toxic ideology is dumped into the building by the theatre’s administrators, poisoning the art and the institution’s audience of decaying, zombified mannequins, filling the theatre’s seats. Dr. Stockmann — the heroic idealist of Ibsen’s play and Vinge/Müller’s production — traces the pollution back to his brother Peter Stockmann, the bureaucrat profiting from the disease-inducing art. 12-Spartenhaus pits Dr. Stockmann’s demands for truth and accountability against Peter’s defense of the theatre’s profitability. Ibsen’s corruptible supporting characters are the theatre’s financial officer and newspaper critics, dramatizing a war between heroic artists and administrative functionaries.

Given its (theatrically) contaminated state, the theatre was locked and spectators were restricted to the lobby for the show’s duration. The live performance inside 12-Spartenhaus was streamed on screens in the lobby, while some action could be seen through windows revealing portions of the building’s interior. Spectators milled about, sat on benches, and picnicked on the floor throughout the show, but there was a palpable frustration that they were barred from the performance. During one show, audience members used power tools to unscrew part of the barrier and enter the performance space. Inside the theatre, characters tauntingly bellowed “the auuuuu-dieeeeennnce,” and chanted “Das Publikum!” For Peter, the public was a monetary calculation, made explicit by his counting the box office take, collected by a figure in Nazi regalia, while a visionary scientist genetically engineered an audience of the future with chicken eggs and gallons of “director’s sperm.” Sebastian Leber wondered, “How pathetic must one’s life be to choose this torture over the real world outside?” (2013). Dirk Pilz more generously considered the production, “super-subversive, avant-garde, refusal-theatre […,] the theatre audience staged as a crowd longing for redemption and foreplay!” (2013). The production dramatized two longings: the artist’s ancient dream to remake the world as fiction, and the audience’s desire to escape the “real world outside” by entering the fantasy.

Figure 7. 12-Spartenhaus, part of the Vinge/Müller Ibsen-Saga. Peter Stockmann with the 12-Spartenhaus administration. Volksbühne-im-Prater, Berlin, Germany, June 2013. (Photo by Angela Roudaut)

The lobby walls separating the audience and interior became a flashpoint in the conflict between the artists and the Volksbühne. The barrier was labeled the “ideological wall,” behind which Aslaksen, the cautious printer of Ibsen’s play, droned his maxim of “moderation.” The wall personified what Vinge/Müller believed the Volksbühne imposes on their art: a barrier enforcing moderation; audiences as corralled consumers; artists as on-demand entertainers. During one performance, Vinge smashed dozens of plastic chairs against the wall’s plexiglass windows separating himself and the audience. Fearing the wall would shatter, the Volksbühne’s technical staff — who manned the lobby — cleared the audience from the area. Over the following weeks, Vinge assaulted the structure with an ax, destroying the wall and ticket booth, requiring technicians to shield audiences from splintering debris. During one attack, Vinge discharged a fire extinguisher through a hole in the wall. Andreas Speichert, a staff technician, inhaled the extinguisher’s discharge and received medical treatment (see Laudenbach Reference Laudenbach2013).

Speichert’s injury raised the tension between the production and the Volksbühne to the breaking point. The performance following Speichert’s injury was cancelled, purportedly because the technician was on medical leave (Leber Reference Leber2013). Vinge/Müller contend the technical staff called in sick to retaliate against the production, pointing out that never before has an entire performance been cancelled because a single member of the technical staff was ill. When the show did reopen, Vinge/Müller received a letter from Frank Castorf, the Volksbühne’s artistic director, cautioning them against their dangerous behaviors. The list of charges included Speichert’s injury, the destruction of food in the lobby’s café (the owner of which was told to seek recompense directly from Vinge), as well as Vinge’s use of his own shit as painting material. Castorf noted that this final warning was an effort to “ensure that [the performance] will no longer affect the health and other rights of employees and the public.” Failure to adhere to these limits would result in “prosecution of relevant actions” and the “termination of our contractual relations” (Castorf Reference Castorf2013). The letter was sent from Bayreuth, where Castorf was staging Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. Germany’s most radical post-reunification director issuing a disciplinary notice from the cradle of the country’s artistic idealism — not to mention one of Hitler’s favorite haunts — was not just ironic; it demonstrated the limits Vinge/Müller had reached.

The next performance of 12-Spartenhaus responded to the letter and the events that inspired Castorf’s admonishments. As the audience gathered outside the Volksbühne Prater, Vinge took to the theatre’s upstairs offices, followed by one of the show’s camera operators. Speaking through a microphone that distorted his voice to the character’s trademark childish warble, Vinge announced in a mixture of German and English that “today only the administration plays,” explaining, “I’m very sorry, but try to be in the ass of the Volksbühne for three years and then you’re fucking nothing in the end” (Vinge 2013). For this performance, the disintegration to “fucking nothing” led Vinge to a grotesque exposé of the Volksbühne’s administrative structures and the discovery of new limits.

Naked but for a T-shirt emblazoned with Wagner’s profile, Vinge read Castorf’s letter while the camera provided a point-of-view image of the text. The document — now in a plastic slipcover — was stained with Vinge’s excrement, which he had used to paste the notice to the Prater’s door during the previous performance. Vinge then placed a Volksbühne poster on the floor, squatted above it, and shat. Using a black marker, he mapped the Volksbühne’s institutional structure using clumps of his shit as landmarks, including the theatre’s administrative offices, café, and finance department. The Prater, a little bubble titled “Art,” was relegated to the far corner of the poster. Using globs of excrement, Vinge traced a path from the Volksbühne to the Prater. Echoes of Ibsen’s contamination narrative are obvious — the pollutant in An Enemy of the People comes from industrial runoff — but Vinge’s concern is the marginal status of art in general and the Saga in particular within the theatre’s larger structure. This point is illustrated with facts written around the poster’s fecal landmarks: The Volksbühne’s budget is 25 million euros, 17 million of which goes to administration; 90% comes from taxpayers, while the remaining 10% comes from ticket revenue. Why then, wonders Vinge, do tickets to 12-Spartenhaus cost 25 euros, arguing that their performances and all other theatre should be free.

Using a fistful of his shit, Vinge blotted out the word “VOLKSBÜHNE” atop the poster. Vinge’s act is antagonistic, but so too is the poster he mocks. The poster’s text is blackletter Schaftstiefelgrotesk (jackboot grotesque), a font favored by and still associated with Nazi propaganda, which the theatre used as part of a provocative advertising campaign. With a thick smear of excrement, Vinge carefully painted his masked face and leaned out the window to display his work to the audience below. “This is the new Volksbühne poster,” he announced, “I’ll put this poster up all around the world; I will show that this is the reality” (Vinge 2013). Before dropping the placard out the window, he paused as children passed by, noting that “the kids have shit in their diapers and I have shit on my poster. This is very dangerous, if someone gets hit by this I will get sued” (Vinge 2013). The poster flutters harmlessly to the ground where onlookers assisted Vinge in affixing the sign to the outside wall of the Prater. The Volksbühne’s faux-inflammatory font is wiped out by the fanatical body’s excretions.

Scatology has long been substance and synonym for art. Hal Foster suggests that its use in the visual arts “tests the anally repressive authority of traditional culture, but it also mocks the anally erotic narcissism of the vanguard rebel-artist” (2015:22). Vinge’s fecal theatrics combine authoritarianism and self-mockery. When Vinge paints, coats his face, or eats his feces, he breaks taboos and draws unflattering connections between creation and excretion. Underlying the antisocial behavior and self-ridicule, Foster notes excrement in art also suggests “a fatigue with the politics of difference […] a strange drive to indistinction, a paradoxical desire to be desireless, a strong call of regression that went beyond the infantile to the inorganic” (24). Here Foster’s analysis falls short. Despite its clownish oppositionality, Vinge’s shit marks the difference between fiction and reality. “This is the reality,” Vinge announces, holding his shit-smeared poster. And “Reality is shit,” Meese tells us, because reality is governed by art’s enemy: ideology.

Meese and Vinge/Müller reinforce distinctions between art and reality, which their predecessors fought to dismantle. For Meese, art creates an idealized, autonomous space within the theatre, lecture hall, or gallery. Vinge/Müller’s art similarly affirms the borders of fiction and reality. Yet the autonomy of an artistic context is too abstract for Vinge and Müller. Art for them is material, hence their impulse to recreate the world as fiction. These artists expose reality’s shittiness to highlight its malleability, its susceptibility to fiction, its inferiority to art. This was the aim of fascism’s ethnopolitical project that sought to reframe reality, to exploit discontent by vilifying Jews and “degenerates,” communists and Roma, all for the sake of theatricalizing the nation; a creative project driven by a belief that it was better to die than cede one’s fantasy to reality.

Figure 8. Vegard Vinge displays the “new” Volksbühne poster outside the Prater office window. 12-Spartenhaus by Vinge/Müller. Volksbühne-im-Prater, Berlin, Germany, June 2013. (Photo by Vinge/Müller)

Vinge demonstrates just this. After adorning the Prater with the “new Volksbühne poster,” Vinge climbs to the second-floor offices, out a window, and onto the theatre’s roof. The camera operator remains at the Prater’s windowsill, livestreaming the action to the lobby, but most of the audience now lines the sidewalk outside. A hundred feet above the street, Vinge walks the length of the theatre’s pitched summit before climbing a 50-foot-high fire escape and onto the adjacent building’s roof. The camera captures how high Vinge has climbed and, more importantly, how far he could fall. Atop the neighboring building, Vinge stretches his arms victoriously, flaunting his shit-streaked mask and Richard Wagner T-shirt. Ibsen’s Master Builder (1893) is a clear referent for Vinge’s stunt, in which the title character tests his physical, spiritual, and artistic limits by climbing his newly erected building and falling to his death before a crowd of onlookers. While Ibsen places Solness’s fatal climb offstage, Vinge ascends in full view of his audience and the unwitting pedestrians of Berlin. While it is happening, it is impossible to know how this Master Builder will end. There is a morbid beauty in watching Vinge traverse the rooftops. It is a scene foreign to art, but familiar in extreme sports: the devotee risking his life. The stunt promises no medal or award; but it fulfills the fanatical commitment to art’s sublime mission.

Vinge walks back along the seam of the roof towards the camera — arms defiantly outstretched — picks up the microphone and speaks: “This is very, very dangerous, we have to shut the performance down because this is sooo dangerous.” Looking across the roof, he concludes: “There is the limit for German theatre” (Vinge 2013). In the final image of the performance, the video feed is replaced by a title card, Eine Kündigung (Cancellation). Vinge/Müller’s Saga, while fanatically devoted to art, is so ambitious, it meets its own ends. “There” beyond the walls of the fantasy, on the precipice of death, “is the limit for German theatre.”

Reality Is Shit

Despite their fanatical dedication to art, Vinge/Müller’s and Meese’s works cannot be reduced to fascist aesthetics. They do not aspire beyond the realm of art into political power. They are didactic, abandoning the ambiguities of reunification-era artists, but in the end the artists’ ideology is theatre. They are less concerned with controlling audiences than dramatizing the value of the fascist imaginary. The work is quite literally fascist in form, not content. Asserting a division between form and content is among the challenges their aesthetics issues. It asks audiences to submit to the demiurgical fantasy and wonder why we hold onto what we previously thought was reality.

Figure 9. Jonathan Meese and Lilith Stangenberg in Lolita (R)evolution (Rufschädigendst) — Ihr Alle seid die Lolita Eurer selbst! by Jonathan Meese. Theater Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany, February 2020. (Photo by Jan Bauer)

Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s modes of engagement with fascism are not equivalent. For the Ibsen-Saga, fascism means sacrifice in the pursuit of the sublime mission of art. Vinge/Müller cow audiences with the creative energies to remake the world as fantasy, and reject the limits ordinary life — what is colloquially known as reality — imposes on art. The Saga dramatizes the demiurge unleashed, but also the implacable borders of common reality. Vinge confronts all presumed enemies of the production to demonstrate that the governing force is art, not institutions or even audiences. For Meese, fascism is a limit case. He performs outlawed images and gestures to subsume them under the power of art, and to demonstrate his fanatical pursuit of art’s sublime mission: to “do one’s duty to art […] the supreme ruler” (Meese Reference Meese2013).

I share my reader’s suspicion. As the history of fascism teaches, reality only yields to fiction through political violence, and art cannot drain objects of their ideology. If this were possible, Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s work would lose much of its power, which arises from the struggle to transform — not the success of transforming — the ideological into art. What seduces is the vision of art that emerges from Meese’s and Vinge/Müller’s efforts: the end of art’s alliance with politics through the power of fantasy. From Meese, we are given the prophecy, while Vinge/Müller realize the vision here, now, in the present. Their art is potent because it reveals that the alternative — a reality suffused with politics and ideology — is shit. Almost anything is better than that.