Introduction

The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) is one of the four major upwelling systems on the eastern boundaries of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and is one of the most productive ocean ecosystems in the world in terms of biomass production and fishery resources (Sakko, Reference Sakko1998; Shannon and O'Toole, Reference Shannon, O'Toole, Hempel and Sherman2003). The Benguela Current runs from around Cape Point in South Africa, along the entire Namibian coastline as far north as the Angola-Benguela front, a permanent frontal feature situated between 15° and 17°S off the coast of Angola and Namibia. A guide to the marine resources of Namibia (Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Carpenter, Roux, Molloy, Boyer and Boyer1999) estimated ‘about 46’ species of sharks, 28 species of batoids and 6 chimaera species present in Namibian waters, or 80 species in total. However, almost no research has been conducted on Namibia's chondrichthyan fauna, meaning that an up-to-date, complete species list has never been generated.

There are currently ten known species of sawsharks (order Pristiophoriformes) worldwide. Of those ten species, the African dwarf sawshark (Pristiophorus nancyae), Kaja's sixgill sawshark (Pliotrema kajae) and Anna's sixgill sawshark (Pliotrema annae) have been recorded from the western Indian Ocean (Ebert and Cailliet, Reference Ebert and Cailliet2011; Weigmann et al., Reference Weigmann, Gon, Leeney, Barrowclift, Berggren, Jiddawi and Temple2020), and Warren's sixgill sawshark (Pliotrema warreni) has been recorded off South Africa and Mozambique only. Warren's sixgill sawshark P. warreni was first described by Regan (Reference Regan1906) from two specimens; one from the coast of KwaZulu-Natal, ‘taken at a depth of 40 fathoms’, and the other from False Bay, South Africa. Both were reportedly about 75 cm total length (TL). The species has been recorded at least as far west as Table Bay, South Africa (over 700 km to the south of the border between South Africa and Namibia; Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Wintner and Kyne2021a) and is thus the only species of sawshark documented from the southeast Atlantic Ocean.

The West African catshark Scyliorhinus cervigoni was first described by Maurin and Bonnet (Reference Maurin and Bonnet1970) from surveys done along the coasts of Mauritania and Senegal, in 1962 and 1968. Its range is currently documented as extending along Africa's west coast between Mauritania and Angola, in waters between 45 and 500 m deep (Finucci et al., Reference Finucci, Chartrain, De Bruyne, Derrick, Doherty and Metcalfe2021).

The bull shark Carcharhinus leucas was first described by Valenciennes in Müller and Henle (Reference Müller and Henle1841). It is found in tropical, sub-tropical and temperate waters, in both coastal and offshore habitats to depths of 164 m (Weigmann, Reference Weigmann2016; Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Dando and Fowler2021b), but mostly in shallower waters to around 30 m depth. In the southeast Atlantic, its range is thought to include Gabon, Republic of Congo, DRC, Angola and Namibia (Rigby et al., Reference Rigby, Espinoza, Derrick, Pacoureau and Dicken2021). However, no published records existed of this species in Namibian waters and it is not commonly encountered by recreational anglers fishing along most of Namibia's coastline (RH Leeney, personal observation), meaning that its presence was unconfirmed and its distribution unknown. The species is euryhaline and moves into estuarine areas and freshwater habitats, where females normally give birth and where bull shark pups can remain for up to five years (Pillans, Reference Pillans2006; Werry et al., Reference Werry, Lee, Lemckert and Otway2012).

Here we report on opportunistic records of P. warreni and C. leucas, which have come to light during research focusing on chondrichthyans in Namibian waters, and a record of S. cervigoni from a survey of chondrichthyan bycatch in deep-water bottom trawl fisheries.

Results

Pliotrema warreni

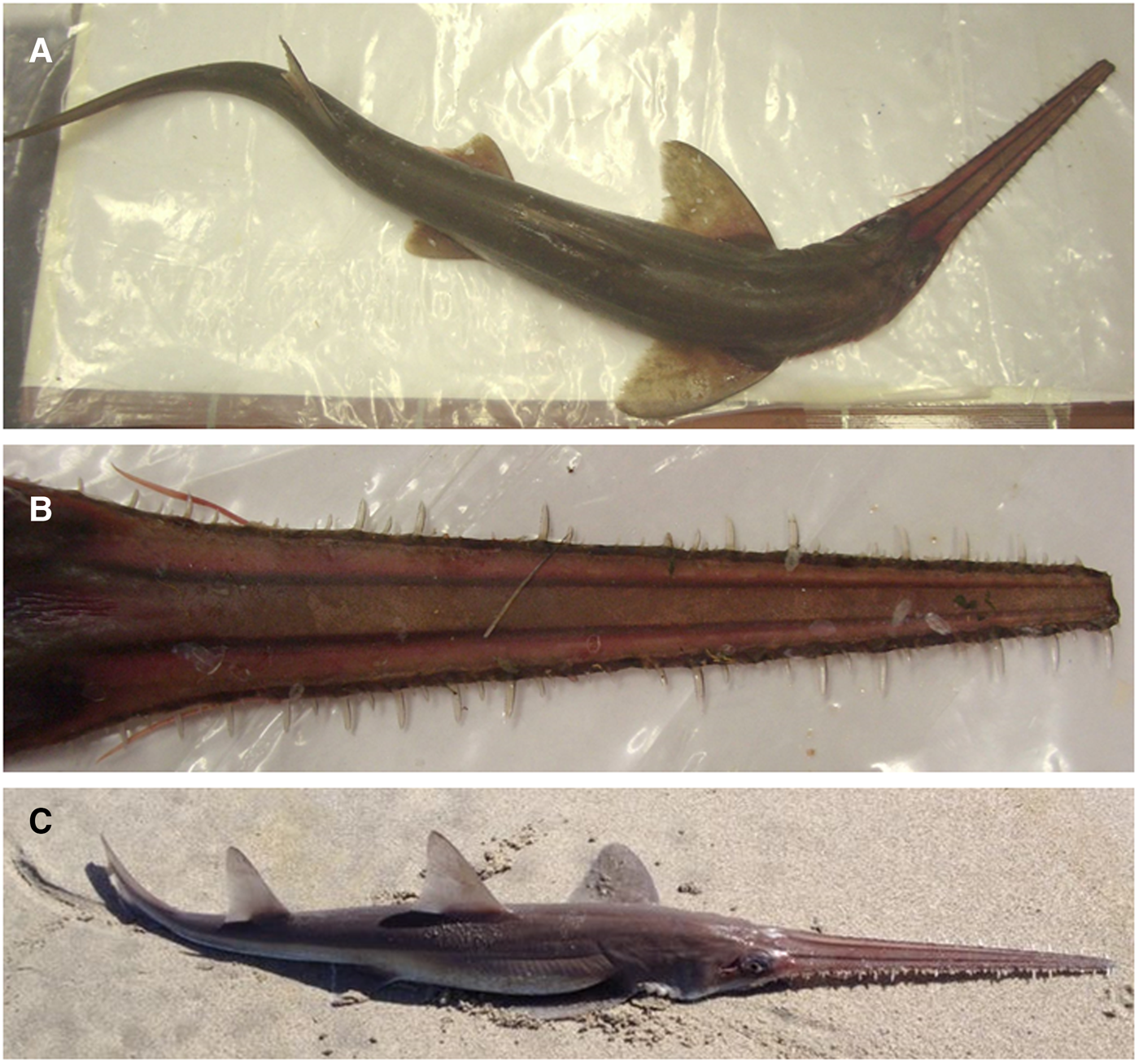

Two new records have been documented. On 24 March 2010, fisheries observers brought a specimen of P. warreni to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources office in Lüderitz, in southern Namibia where it was photographed (Figure 1A, B). The specimen was captured during an offshore commercial fishing trip in southern Namibian waters and was about 110 cm TL. No further information pertaining to the animal or the location of capture was recorded.

Figure 1. Specimens of Pliotrema warreni recorded in Namibia in (A) and (B) March 2010 (photo: Kolette Grobler) and (C) February 2014 (photo: Melanie Honiball).

On 23 August 2014, recreational anglers were fishing from the shore in an area known as the Canopy Area, about 60 km north of Henties Bay, Namibia. They came across a sawshark on the beach (Figure 1C), which they estimated to be between 70 and 100 cm in TL and weighing about 1 kg. Apart from a scavenged eyeball, the shark was relatively fresh, suggesting that it was recently dead or perhaps even alive when it washed ashore. Alternatively, it may have been caught by a shore-based angler and left on the beach. This practice was not uncommon in Namibia in the past, and angler-caught skates have been observed discarded on the beach in southern Namibia as recently as 2023 (RH Leeney, personal observation).

Photographs of the first animal reveal barbels originating close to the base of the rostrum, although their exact origins can only be estimated. This supports the identification of both specimens as P. warreni (Weigmann et al., Reference Weigmann, Gon, Leeney, Barrowclift, Berggren, Jiddawi and Temple2020), which has barbels originating about two-thirds of the distance between the rostrum tip and mouth and is the only saw shark species documented from the south-eastern Atlantic.

Scyliorhinus cervigoni

As part of a longer-term assessment of chondrichthyan bycatch in deep-water trawl fisheries (>200 m) for hake (Merluccius spp.) off Namibia, a small catshark was recorded (Figure 2). The specimen was caught on 7 March 2023 during a north-south trawl between S 18° 06.1′ E 11° 27.4′ and S 18° 20.1′ E 11° 27.0′. The shark was female and measured 47.8 cm TL. A fin clip was taken, which will undergo genetic sequencing to confirm the identification, but morphological features including a stout body and broad, fairly flat head; the second dorsal fin much smaller than the first; scattered large and some small dark spots along body and seven dusky saddle marks centred on dark spots on the midback (Figure 2) indicate this was a West African catshark.

Figure 2. A West African catshark (Scyliorhinus cervigoni), bycaught by a bottom trawler operating in northern Namibia, March 2023. Photo: Ruth H. Leeney.

Carcharhinus leucas

Conversations with several anglers and tour operators who arrange angling trips to northern Namibia revealed that bull sharks can be caught in northern Namibia, in and close to the Kunene River which forms the border with Angola. One such operator recounted that between November 2021 and March 2022, an estimated ‘10–12’ bull sharks were caught just upriver of the Kunene River mouth, from the riverbank on the Namibian side and just south of the river mouth, along the Namibian coast (L. Krause pers. comm. 27 April 2023). These animals were estimated to weigh between 8 and 15 kg each, or at least 100 cm in TL. A photograph taken during that period confirmed the species as C. leucas (Figure 3). This tour operator also noted that bull sharks have been caught at least 5 km upriver of the Kunene River mouth. Previous studies of fish fauna in the Kunene River have not documented bull sharks (Hay et al., Reference Hay, van Zyl, van der Bank, Ferreira and Steyn1997).

Figure 3. A juvenile Carcharhinus leucas caught by Leon Krause (pictured) close to the Kunene River mouth. Photo: Lindie Krause.

Discussion

Pliotrema warreni is listed as least concern on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species (Pollom et al., Reference Pollom, Rigby, Bennett, Fennessy, Gledhill, Leslie, Sink, Winker, Pacoureau, Herman and Cheok2020). Sawsharks are inherently susceptible to capture in trawl fisheries as their rostra are easily entangled in nets. They are captured as bycatch in demersal trawl fisheries in Mozambique (RH Leeney, personal observation) and South Africa and may also be caught by the South African hake longline fishery (da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Booth, Dudley, Kerwath, Lamberth, Leslie, McCord, Sauer and Zweig2015). The deepwater bottom trawl fisheries for hake (Merluccius capensis and M. paradoxus) and monkfish (Lophius vomerinus) in Namibia may therefore pose some risk to this species, which inhabits depths of between 10 and 915 m, but usually between 60 and 430 m (Weigmann et al., Reference Weigmann, Gon, Leeney, Barrowclift, Berggren, Jiddawi and Temple2020). Pliotrema warreni may therefore have been more common in this region in the past, but been depleted by fisheries, although there are no historical data to support or refute this. Alternatively, the scarcity of records of this species along Namibia's coast may suggest that the records reported here represent vagrants or animals at the westernmost edge of their range. If the latter is the case, any threats in Namibian waters are unlikely to significantly impact the population.

Scyliorhinus cervigoni is listed as data deficient on the IUCN Red List (Finucci et al., Reference Finucci, Chartrain, De Bruyne, Derrick, Doherty and Metcalfe2021). There is no information available on threats faced by this species. The record reported here suggests that it is caught at least occasionally in bottom trawl fisheries in Namibia and thus probably in other parts of its range. Ongoing data collection in bottom trawl fisheries in Namibia will reveal the frequency with which this species is bycaught.

Carcharhinus leucas is listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Rigby et al., Reference Rigby, Espinoza, Derrick, Pacoureau and Dicken2021). It has not previously been reported from specific habitats in Namibia. Given that it inhabits solely tropical and subtropical waters, this species is unlikely to be encountered much further south (in Namibia) than the area from which the records in this paper occurred. Data on the catches of shore-based anglers from numerous sites along the coast (RH Leeney, unpublished data) suggest that bull sharks are solely encountered around the mouth of Kunene River and at least up to 5 km upriver from the mouth, but probably nowhere else along the Namibian coast.

Sizes at birth vary considerably for C. leucas populations in different parts of the world. Around Réunion Island, size at birth has been estimated to be between 70 and 80 cm (Pirog et al., Reference Pirog, Ravigné, Fontaine, Rieux, Gilabert, Cliff, Clua, Daly, Heithaus, Kiszka, Matich, Nevill, Smoothey, Temple, Berggren, Jaquemet and Magalon2019), and local anglers reported free-swimming juveniles of 68–79 cm (T Poirout, personal observation, reported in Pirog et al., Reference Pirog, Ravigné, Fontaine, Rieux, Gilabert, Cliff, Clua, Daly, Heithaus, Kiszka, Matich, Nevill, Smoothey, Temple, Berggren, Jaquemet and Magalon2019). In the western North Atlantic, size at birth was calculated as 60.8 cm for males and 62.2 cm for females (Natanson et al., Reference Natanson, Adams, Winton and Maurer2014). The individuals reported from the Kunene River mouth area, which were estimated to be at least 100 cm TL, are therefore unlikely to have been neonates.

Carcharhinus leucas uses estuaries as pupping and nursery grounds (Whitfield, Reference Whitfield1996, Reference Whitfield1998), although it is not currently clear whether they use the Kunene River in this way. The life history of this species involves multiple habitat types including estuaries and freshwater habitats, which are often ecosystems already significantly modified or impacted by humans (Strayer and Dudgeon, Reference Strayer and Dudgeon2010). They are thus likely to be exposed to a far wider array of threats than strictly marine species. The threats to C. leucas in the limited Namibian part of their range are likely to be minimal with most being caught by recreational anglers. The northernmost part of the Namibian coastline is uninhabited and is accessible only by offroad vehicles. The Skeleton Coast National Park extends from the Ugab River, northwards to the Kunene River (which forms the border between Namibia and Angola) and from the coastline to between 30 and 40 km inland (Ministry for Environment, Forestry and Tourism, 2021). The northern section of the park (north of the Ugab River gate) is off-limits to all vehicles except for tour operators who hold a concession. This at least ensures that C. leucas and other chondrichthyans in the area are subject to only limited pressure from recreational anglers, and the anglers visiting this region are usually part of organised tours and are encouraged to practise catch-and-release. In addition, the Kunene River mouth lies between two protected areas, Iona National Park in Angola and Skeleton Coast Park in Namibia, and the governments of Angola and Namibia have signed a Memorandum of Understanding to link these two parks as a transfrontier park. However, there is no monitoring of the park region and inappropriate development, including mining and prospecting, has been identified as a significant threat to the river mouth (Paterson, Reference Paterson2007).

A comprehensive list of chondrichthyan species present in Namibian waters is currently lacking. The addition of two new species and more precise, verified information on the range of a third species will contribute to the development of a more complete list, which is an important step towards managing and monitoring chondrichthyans and encouraging more in-depth research on these species in Namibia.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, R. H. L.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Melanie and Morne Honiball for contributing a record of P. warreni, and to Leon Krause for providing information on C. leucas catches, and to Hayley Brand for assistance with bycatch data collection. D. A. E. would like to thank the Save Our Seas Foundation Grant 594, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity. The authors thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments, which greatly improved this manuscript.

Author contributions

R. H. L. collated the reports and wrote the manuscript. D. A. E. advised on species diversity in Namibia and contributed to writing the manuscript. K. G. collected data on a saw shark specimen and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Financial support

The Namibia's Rays and Sharks project is funded by the Shark Conservation Fund, a project of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. The smartphones and hand-held GPS units used for the collection of bycatch data were provided through an equipment grant from Idea Wild.

Competing interests

None.