This study was born of one of the tenets of my own teaching: if you expect students to learn, you must meet them where they are. For today’s college students, where they “are” is on social media, but where they “aren’t” is engaged in political and civic discourse. Fully 90% of young adults, 18 to 29 years old, reported actively using social media (Perrin Reference Perrin2015); however, looking for news and information is hardly their primary motivation (American Press Institute 2015).

Is it possible, however, that college students would use social media for political education if they had an opportunity to experience how to do so constructively? Could literacy in utilizing these platforms serve as a conduit to political engagement? This study explores the possibility that the capacity to learn about their political environment may be a potential step toward becoming engaged citizens by assessing students’ use of media to learn about politics and then exposing them to the concept of social media learning using Twitter to learn about a specific political issue or event. The impact of this exercise then is gauged both directly through the use of a pretest/posttest survey and indirectly by examining the students’ post-exercise blog posts. I conclude that social media learning is an opportunity to correct students’ perceptions about the use of social media as an information source. It also provides a pathway for deeper learning on political issues because it makes learning about an issue more appealing and engages students who are less interested in a traditional classroom delivery.

I first outline concerns about the current college-aged generation that establish the need for political scientists to purposefully use pedagogical tools that combat political disengagement. I then review how Twitter can be one such pedagogical tool. The remainder of the article explores a case study in which I use Twitter to establish with students a Personal Learning Environment (PLE), which is defined as “tools, communities, and services that constitute the individual educational platforms that learners use to direct their own learning and pursue educational goals” (Educause Learning Initiative 2009). I demonstrate how this PLE (1) provided a pathway for enhanced media literacy and deeper learning, (2) made learning about an issue more appealing, and (3) engaged students who are less interested in a traditional classroom delivery.

I demonstrate how this PLE (1) provided a pathway for enhanced media literacy and deeper learning, (2) made learning about an issue more appealing, and (3) engaged students who are less interested in a traditional classroom delivery.

MILLENNIAL DISENGAGEMENT AND DISINTERESTFootnote 1

For some time now, scholars have been exploring the possibility that the unprecedented access to information that the internet provides young people has the potential to greatly expand their political knowledge and democratic engagement (Boulianne Reference Boulianne2009; Galston Reference Galston2001; Katz and Rice Reference Katz and Rice2002; Mitchelstein and Boczkowski Reference Mitchelstein and Boczkowski2010). However, there is only limited empirical evidence showing this to be the case.

The 2008 presidential election was a unique opportunity to examine the social media use of young people. Although they participated at a higher rate than in other recent campaigns, research on the online participation of younger citizens showed that whereas there was a correlation between online participation and offline engagement, the quality of the online participation was low (Conroy, Feezell, and Guerrero Reference Conroy, Feezell and Guerrero2012). A study of Swedish adolescents also demonstrated this relationship and found the users’ content to be negatively related to political knowledge (Östman Reference Östman2012). Other studies showed that young people are online but not necessarily learning from their activities. Gleason’s (2016, 31) examination of teenage social media use revealed that teens use social media for “self-expression, communication, friendship maintenance, and information sharing,” not political discussion. Bridges, Appel, and Grossklags (Reference Bridges, Appel and Grossklags2012) found that given an engagement task (i.e., contacting an appropriate government official), fewer than 30% of the students could use internet resources—including social media—to correctly and independently complete the task. The authors attributed this to a severe lack of understanding in how to utilize web-based resources to appropriately engage with elected officials. Pew Research Center found that those who engage in politics online are already engaged offline (where a majority of political discussions take place), calling into question the value in online political engagement (Smith Reference Smith2013).

These findings suggest that it is possible that young people could be more successfully engaged with political information if they better understood how to navigate the social media environment. However, Dahlgren (Reference Dahlgren2013) argued that the failure of the internet to live up to its promise should not be viewed as failure because the potential still exists. It remains possible, then, that young people could use the internet generally and social media specifically as a medium for deeper learning and engagement if they had guidance on how best to do so.

This opportunity is uniquely in the wheelhouse of political science; civic engagement was a founding premise of the discipline. As Thomas and Brower (Reference Thomas and Brower2017) pointed out, although other disciplines may encourage and prepare students for meaningful civic engagement, this preparation may lack training in the realm of politics and citizenship; responsibility for this essential component of civic engagement may fall squarely on political science. As such, many political scientists continue to seek ways to deepen the commitment to fostering civic engagement (Matto et al. Reference Matto, Rios Millett McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2017). As the use of social media in the sphere of higher education has become more common and varied, many political scientists have turned to Twitter as one means of potentially delivering on this commitment.

TWITTER AS A TEACHING TOOL

For college students, varied use of social media has become an integral component of their education (Dabbagh and Kitsantas Reference Dabbagh and Kitsantas2012; McLoughlin and Lee Reference McLoughlin and Lee2010; Smith, Salaway, and Caruso Reference Smith, Salaway and Caruso2009; Solomon and Schrum Reference Solomon and Schrum2014). One such social media platform is Twitter. Social media in general, and Twitter in particular, offers an opportunity for students to engage in less-formalized learning experiences. In discussions of integrating informal learning techniques into higher-education pedagogy, scholars often refer to the value of cultivating PLEs. PLEs are desirable because they are more likely than traditional teaching methods to integrate both formal and informal learning (McLoughlin and Lee Reference McLoughlin and Lee2010). The use of Twitter in a course is one way to build a pedagogy that uses PLEs.

Since its founding in 2006, Twitter and its users are ever-expanding how the platform is used for political and policy news, discussion, and advocacy (Jungherr Reference Jungherr2014); thus, it offers an increasingly rich opportunity for students to access and learn from information about politics and public policy. Kassens-Noor (Reference Kassens-Noor2012) examined how Twitter can be used in a university-classroom setting. Her study revealed how Twitter can be used as a teaching device for outside learning using real-life examples and experiments to expand informal learning. She found that Twitter required more time investment than the use of individual diaries and that Twitter users provided far fewer overlap examples than the traditional group (i.e., diaries), indicating a potentially farther-reaching learning experience. However, Lin, Hoffman, and Borengasser (Reference Lin, Hoffman and Borengasser2013) revealed that although undergraduates and graduates enjoy using Twitter to consume information, they rarely use the social media site to comment on a topic or express their own opinions—two activities essential to democratic engagement and deeper civic learning (Colby Reference Colby2007).

A 2012 meta-analysis of the use of student microbloggingFootnote 2 as a pedagogical tool found that, across disciplines, research was incredibly varied; therefore, strong conclusions were difficult to draw. However, the analysis suggested that student microblogging had the capacity to “encourage participation, engagement, reflective thinking as well as collaborative learning” (Gao, Luo, and Zhang Reference Gao, Luo and Zhang2012, 783).

TWITTER IN THE POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASSROOM

In political science, Pele (Reference Pele2012) addressed this potential by demonstrating that Twitter can allow students to create concise arguments around issues in political philosophy classes while also linking to more in-depth information. Twitter also can prompt and encourage the free-flowing exchange of ideas when used to conduct class (Dunlap and Lowenthal Reference Dunlap and Lowenthal2009). In addition to potential applications of Twitter in a political science curriculum as a best practice for course-specific learning outcomes, researchers have found the value Twitter may play in enhancing civic engagement; however, this research remains limited. Woodall and Lennon (Reference Woodall and Lennon2017) focused on measuring online political engagement and found promising results. Using control and experimental groups, they found that students in the group that used Twitter in their political science course had higher levels of political knowledge and online political engagement than those in the control group who did not.

Using control and experimental groups, they found that students in the group that used Twitter in their political science course had higher levels of political knowledge and online political engagement than those in the control group who did not.

Of course, online political engagement is not the same as “real-world” civic engagement, and the limited research in this realm has been less promising. In a content analysis of tweets by students required to engage on the platform throughout their political science courses, Caliendo et al. (2015, 283) found that Twitter is not necessarily a “silver bullet” for encouraging real-world civic engagement. These researchers found that students enjoy using Twitter as part of their coursework but did not find evidence that it was useful in encouraging their civic engagement. Measures of efficacy, political interest, and civic engagement were not affected by its use. What no study appears to assess is whether Twitter use offers an opportunity for students to gain media literacy on the platform in a way that is conducive to learning that could enhance their potential for civic engagement.

PEDAGOGICAL LIMITATIONS

Numerous pedagogical arguments are made against the use of Twitter in higher education. The platform may offer a lack of “thinking space” (Kassens-Noor Reference Kassens-Noor2012), prompting a lack of depth in student discussion.Footnote 3 More generally, the teacher–student relationship is more complicated in an online environment, and some scholars believe this is a detrimental distraction from learning (Sandholtz, Ringstaff, and Dwyer Reference Sandholtz, Ringstaff and Dwyer1997). Students also may be encouraged by the character limit to use bad grammar, and the potential of internet addictions or time and financial costs are considerations as well (Dunlap and Lowenthal Reference Dunlap and Lowenthal2009). Inevitably, students enrolled in a traditional-delivery classroom (i.e., face to face) could lack Twitter savvy, be confused by the platform, or not take social media activities as seriously as other assignments.

Students enrolled in a political science course also may have self-selected and thus already have higher electronic political engagement, perhaps higher political media literacy, and certainly more political interest and/or knowledge (Caliendo et al. Reference Caliendo, Chod, Muck and Schreck2015). These were considerations in the execution of this study to mitigate any risk of the exercise being less successful. For example, the course used in this exercise fulfills a general-education requirement but also is a prerequisite for in-major (i.e., political science and public policy) degrees. As such, some students would fit into the set of concerns that Caliendo et al. (Reference Caliendo, Chod, Muck and Schreck2015) expressed in their research using Twitter in political science classrooms, but they were the minority of subjects in this examination. Students—who are guaranteed laptops as a condition of their enrollment at this institution—also were from an in-person class and were given instruction in how to participate in the exercise—as well as how to use the Twitter platform in advance, if needed.

CLASS ON TWITTER

The construction of the Class on Twitter (COT) exercise was guided by the framework proposed by Dabbagh and Kitsantas (2012, 6) to utilize social media to promote self-regulated learning in PLEs. In this framework, students were (1) provoked to manage their “personal information management,” (2) participate in social interaction, and (3) synthesize information. Students first prepared for participating in the COT by generating and following a list of appropriate stakeholder accounts, reflecting level 1 of this framework, in which students are expected to manage their personal access to information (see online appendix A for specific instructions for the exercise).

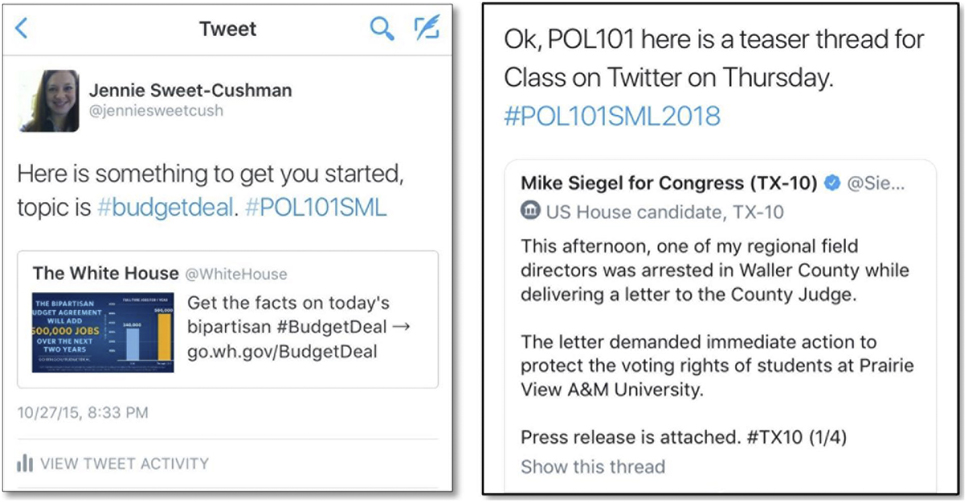

Level 2 in Debbagh and Kitsantas’s (Reference Dabbagh and Kitsantas2012) framework is instituting social interaction by hosting a class session on Twitter. The COT consisted of introducing the students to a trending topic in American politics (e.g., congressional budget crisis) via a brief tweet that I provided (figure 1).

Figure 1 Samples of Initial Tweets

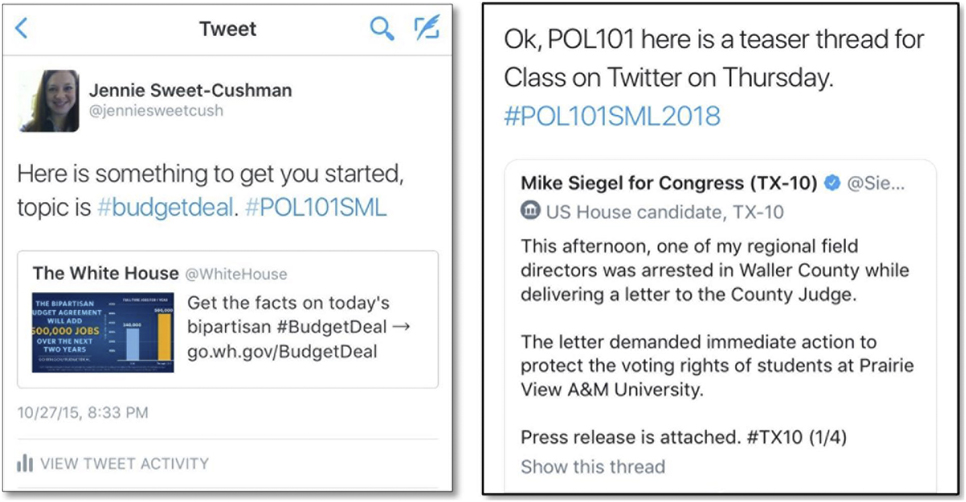

Observationally, several things were apparent during the COT. First, with minimal guidance on following appropriate stakeholders (e.g., elected officials, media outlets, interest groups, and government agencies), students had little trouble finding information they felt was reliable, moving quickly from not having heard about the issue being discussed to being able to accurately articulate many of the details of the issue, upsides, and criticisms. Second, they did not immediately rely on their own political biases to evaluate the information (figure 2). Third, they seemed to genuinely grow the dialogue off the information shared by their classmates—a truly rich and diverse discussion.

Figure 2 Final Poll

One notable observation in conducting this exercise was that there are consistently different patterns of participation between in-class and Twitter discussions. Frequently, students who rarely, if ever, speak up in class were more engaged in the Twitter discussion. Also of note is how these conversations persisted beyond the COT discussion. In one use of this exercise, the COT lasted only a little more than an hour, but nearly all of the students continued the discussion after I left the conversation; the topic frequently emerged in in-class discussions following the exercise and, reportedly, in conversations students had outside of the classroom.

Several students continued to use the hashtag to share information after the assignment was completed, despite obligations of the assignment having been met. My final provocation to the students was a Twitter poll asking whether they ultimately felt the budget deal was a good one. It is interesting that support for the deal did not reflect preexisting political biases that the students professed in class (see figure 2).

Following the COT and consistent with level 3 in the framework, students wrote a 1,000-word reflective blogpost. In evaluating whether course learning goals were met, they demonstrated student learning on the chosen topic, with nearly all of them showing an appropriate depth and breadth of knowledge on the topic, given their brief exposure to a new political topic.

Utilizing this unique application of Twitter in a political science classroom, I examined the following questions about the use of Twitter as an element of a student’s PLE:

1. Effectiveness: Will students view social media as a more effective way to learn about issues of importance to them?

2. Learning: Can media literacy be enhanced to demonstrate learning via social media (i.e., engaging in civic dialogue, understanding issues of public policy, and identifying stakeholders)?

3. Enjoyment: Do students enjoy the use of Twitter as an element of a traditional face-to-face political science course?

RESULTS

I assessed these questions both quantitatively through the use of a student survey, and qualitatively by analyzing student blogposts following the COT.

Pre-Post Survey

An expanded description of this methodology is in online appendix B.

Pretest Assessment Findings

Students offered interesting contradictions in the pretest. First, as figure 3 shows, they indicated that—to the extent they do use media to learn about political issues—they are most likely to do so on social media.

Figure 3 Student Reports of Most Commonly Used Media

Note: Response categories are not mutually exclusive.

Despite indicating that they rely on social media for information before the COT, the students were not necessarily confident in their abilities. Although a remarkable 89.1% (n=30) believed that they were at least somewhat comfortable discerning diverse viewpoints, less than 40% (i.e., 39.4%, n=13) felt very confident that they could identify sources that they could trust or those that were objective (i.e., 33.3%, n=11). Furthermore, despite using social media, they did not seem to believe it is necessarily a good place to go for news (figure 4).

Figure 4 Student Evaluations of Social Media as a Source for Political Information

Only 18% of students thought social media was a good source for news. They also varied significantly in how confusing they think political news can be (figure 5). Whereas nearly a majority (48%, n=16) said they were unlikely to avoid political news because it was too confusing, the remainder were unsure or likely to do so.

Figure 5 Student Reports of How Likely They Are to Avoid Political News

Changes Pre to Post

The pretest revealed students who were likely to go to social media for political news but were not confident in its ability to help them be better informed or less confused about political issues. This provided a baseline by which to evaluate the effectiveness (question 1) and potential (question 2) of Twitter as a component of a PLE. Each of the following findings is from paired-samples t-tests to compare the various dependent variables before and after the exercise.

There were distinct differences among students that, on the posttest, indicated they do and do not use social media for political news. For non-users, the exercise had no statistically significant effect on their interest in political news, confidence in using social media, or thoughts about social media as a forum for learning about politics. Notably, the one exception to the non-findings for non-users was that they were more likely to report that they felt more confident in finding news sources with diverse viewpoints (on a scale of 1=not at all confident to 3=very confident). As figure 6 demonstrates, there was a statistically significant difference between the pretest (M=2.11, SD=0.601) and the posttest (M=2.56, SD=0.527; t=-2.539 (df=8), p=0.035) on this measure.

Figure 6 Post-Exercise Confidence in Ability to Identify Diverse New Sources, by Reported Use of Social Media

Impressions of students who intend to get their news elsewhere should be of less of interest than those who are committed to using social media to learn about political issues; they are theoretically building a PLE that incorporates the use of social media. Users of social media demonstrated evidence (figure 7) that the COT made them feel more positive

Figure 7 Feelings about and Interest in Politics on Social Media, by Reported Use of Social Media

Footnote 4 and interested in learning about political issues on social media.Footnote 5 As opposed to before the COT (M=1.57, SD=0.746), students felt social media was a better place to search for political information (M=2.14, SD=0.655; t=-3.009 (df=20), p=0.007).

These findings suggest that there was limited value of the exercise for non-users of social media, but that for those most likely to use social media to gather political information (i.e., the users), the COT made them feel better about relying on social media for their political information and provoked further interest.

Users also were more interested in learning about issues on social media following the COT (M=4.33, SD=0.577) than they were before the exercise (M=3.86, SD=1.236; t=-1.943 (d=20), p=0.056). The non-users’ decline in interest post-exercise also was statistically significant, perhaps indicating that they were willing to try the idea but were unconvinced. They also reported lower positive feelings toward politics on social media—although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

These findings suggest that there was limited value of the exercise for non-users of social media, but that for those most likely to use social media to gather political information (i.e., the users), the COT made them feel better about relying on social media for their political information and provoked further interest.

Qualitative Assessment

Casually and observationally, students love the COT. I draw, then, from their comments in their post-exercise reflection blogposts about the exercise to evaluate this final research question regarding student enjoyment. Whereas a few students were somewhat overwhelmed by the exercise, most expressed distinct pleasure with Twitter as a course-delivery method.Footnote 6 One student wrote:

There is no such thing as “it’s too long. I didn’t read” or “it’s too complicated. I don’t understand” with Twitter. With the limited 140-character message, Twitter is the perfect platform for people who want to learn about the basic information of something as complicated as politics. If you use the right hashtag and follow the right stakeholders, it is easy to learn about politics and government bills, and what opinions people have about those issues.

Others echoed a newfound appreciation for Twitter, one that has the potential to follow them far beyond the classroom or even their undergraduate experience:

Twitter provides an easy forum to debate the issue with fellow classmates and peers. I was able to discover the opinions of elected officials, along with the average American. Seeing my fellow classmates’ opinions helped me gain perspective on this issue, as well as keep an open mind about the opinions of others. Researching this issue through social media equipped me with a tool to become more informed on future debates and issues.

Perhaps more important, many of the students—in both their blogposts and my conversations with them—enjoyed gathering political information using Twitter and indicated that they had renewed faith in using social media to stay informed and knowledgeable about politics and public policy. As another student concluded:

I thought having class on Twitter as a method of researching a current issue was definitely one of the most interesting class experiences I’ve ever had. I loved that it was a true-to-life demonstration on how people in this day and age discover and understand current issues.

As an instructor, I was pleased with the depth and breadth of learning demonstrated (i.e., the median grade was 87%) and students were pleased with the delivery.

CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

In conclusion, my observation of the process and assessment of student learning, as well as student perspectives, indicates that there is great potential for social media learning as a pedagogical tool in political science. In addition to using the COT to inject a new element into a traditional curriculum, I offer three important findings from four years of utilizing this exercise. The first two speak to the power of integration of social media into student PLEs—in an effort to provoke deeper learning around political issues, a precursor to civic engagement. The third finding is a pedagogical best practice around student engagement more generally.

First, the COT promotes a pathway for enhanced media literacy and deeper learning. Pretest data and my discussions with them showed—before the exercise—that students seemed confident that they could appropriately investigate a political issue if they had the time and motivation to sort through the biased and confusing information available. However, when required to do so by looking for stakeholders to follow for the COT exercise, few felt confident in how to approach it and required much guidance in the basic first step of information gathering. In this instance, then, social media corrected their perception that they could be easily informed, if only they wanted to be so.

After they acknowledged that discerning quality sources and information literacy was a bigger hurdle than they initially assumed, the networked nature of social media provided a pathway for deeper learning. After students commit to growing their social media presence in a way that includes sources relevant to politics and public policy, it becomes a part of their PLE and has the potential for continued learning. It appears that from posttest data that students who were committed to social media following the exercise may have interest in sustaining their connection to political information via social media. They indicated that they were more confident in social media as a source for political information and more enthusiastic about following political news. This seems to be a good basis for developing their own civic engagement—if not in real life, then perhaps online, as Woodall and Lennon (Reference Woodall and Lennon2017) also found in their use of Twitter.

Second, students initially showed only modest interest in learning about political issues, which should not be unexpected in a course composed of students fulfilling a general-education requirement. However, for students who emerged from the exercise still willing to use social media to learn about news, the COT seems to have made learning about an issue more appealing. They simply enjoyed learning in their “natural environment.” Average college students are deeply immersed in social media in their personal life. Using Twitter as a format by which they experience their academic as well as personal life may mean that students feel empowered to learn about political topics that might otherwise seem removed from their own life. Before this exercise, students reported using sources to learn about issues that would require purposeful seeking—cable news and national newspapers—sources that would not be integrated into their typical social media habits. Arguably, although being actively engaged in consuming political news might not predict offline civic engagement (Caliendo et al. Reference Caliendo, Chod, Muck and Schreck2015), it might be a necessary condition for it.

Third, the COT outcomes were by design, but one was unexpected. The exercise engaged students who were less engaged in traditional classroom delivery. Consistent with Ferriter’s (Reference Ferriter2010) work highlighting the benefits of incorporating different learning styles into the classroom, I found that the patterns of class participation that existed in the traditional face-to-face classroom delivery method broke down in the COT delivery. That is, students who were very participatory in the classroom were somewhat less so in the Twitter environment. More importantly, in some cases, students who infrequently participated in the classroom were more likely to retweet and comment on Twitter. Social media learning, then, may not only be an effective way to guide students in learning about political and policy information, but also a way to engage a larger (or different) population of students. Junco, Heiberger, and Loken (Reference Junco, Heiberger and Loken2011) and Greenhow and Gleason (Reference Greenhow and Gleason2012) would seem to support this idea in their work on college students and campus engagement. They found that students who were engaged on Twitter with their peers (as opposed to those who were not) were more engaged and showed better academic progress. Why would this not also be true in the classroom?

Testing the idea of promoting more expansive student classroom engagement empirically is one future consideration. In particular, considering how students would map their real versus ideal PLEs could add to this conversation about in-classroom engagement, and also—potentially—beyond the classroom. There would also be value in experimenting with other types of political science courses and with prolonged engagement over a semester.

More specific to the charge felt by political scientists to encourage student civic engagement, longer-term research is needed to see if students move from learning about political topics in class to being engaged online to engaging in their own political environments in college and beyond. Future research could and should examine the growth of confidence and literacy with continued usage of a social media platform both in class and following completion of a course. Importantly, if a single introduction/intervention to a constructive use of Twitter has the potential to engage students in a smarter more meaningful way around political news and information, perhaps we, as political scientists, should be incorporating more of it into our courses.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000933