Nidotherapy (the ‘i’ is long) has come about from the frustrations of exercising evidence-based treatment options in a minority of patients who despise them all with equal fervour. It is a treatment that systematically adjusts the environment to suit the needs of a person with a chronic mental illness, personality disorder or similar long-term disability. The name is derived from the Latin nidus, or nest, as a nest, particularly a bird’s nest, represents one of the best natural examples of an environment adjusted to an organism (Reference TyrerTyrer, 2002). Although taking the environment into account is part and parcel of clinical management, the systematic manipulation of the environment, often in a subtle way to include both physical and social environments, has not been formalised before. Many reading this article will regard such action as the exercise of common sense rather than any special type of intervention and will be sceptical about formalising it under a fancy title such as nidotherapy. They may be right, but I should like all to suspend judgement until they have further evidence of the value of this approach expressed in a more formalised manner.

Principles of nidotherapy

There are five essential principles of nidotherapy: collateral collocation, the formulation of realistic environmental targets, the improvement of social function, personal adaptation and control, and wider environmental integration involving arbitrage (Reference Tyrer, Sensky and MitchardTyrer et al, 2003) (Box 1). These need amplification.

Box 1 Principles of nidotherapy

Collateral collocation

Seeing the environment from the patient’s point of view

Formulation of realistic environmental targets

Setting clear goals for environmental change

Improvement of social function

If the targets are right, social function will improve; if it does not improve, the targets need to be reassessed

Personal adaptation and control

Throughout nidotherapy the patient takes the prime responsibility for the programme

Wider environmental integration and arbitrage

Involving others, particularly a trusted arbiter, in resolving change that may not be desired by others

Collateral collocation

This alliterative couplet describes the task of seeing the environment through the eyes of the patient, a combination of ‘standing side by side’ and ‘standing in each other’s shoes’. The first task in nidotherapy is to try to interpret the environment as seen by the patient in a way that gives greater understanding of perceived priorities. Although we do this in clinical practice repeatedly, there is a tendency to be paternalistic in proposing what seems a reasonable environmental adjustment (i.e. usually one that we agree with) and rejecting others that seem to us to be unsatisfactory or unrealistic. In collateral collocation, all external judgement is suspended in the first instance and a full environmental analysis of the patient’s current situation is made and potential areas of change outlined. Clearly, such an activity is focused to some extent on those needs that are judged to be relevant to mental health; others are usually presumed to be of lesser importance but always need to be considered, as they may be much more important than originally thought.

In the second phase of analysis, the potential environmental changes identified by others involved in care (an individual therapist or joint workers, or indeed the whole clinical team) are also defined in detail. This list may be very different from that provided by the patient but both need to be spelled out initially. The lists for one patient, a refugee from a Muslim country, and his nidotherapist, are shown in the first two columns of Table 1.

Table 1 Environmental analysis and subsequent compromise action

| Environmental area | Patient’s first environmental analysis | Clinical team’s environmental analysis | Agreed compromise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort: warmth | Complete draught exclusion in flat and better heating | Serious deficiencies in heating arrangements in flat | Patient agrees to be moved to a new, smaller, centrally heated flat |

| Finance | Every day to have enough money for his needs | Poor personal control over finances: friends borrow his money without returning it, manipulate and exploit him | Clinical team act as patient’s appointee and give him money three times a week, always keeping some in reserve |

| Leisure | To be close to his friends and late-night café culture | The friends he meets are not thought to be a good influence on him so this wish is not regarded as very important | Compromise solution: moved closer to social network (see comfort above) but encouraged to have more activities elsewhere during the day |

| Security | To feel safe when alone at home | Is vulnerable and unable to deal with potential conflict | Extra locks fitted at main door of building |

| Status: self-esteem | To live in surroundings where he can be taken seriously by friends, relatives and professionals | No special opinion: he appears to have good self-esteem already | Money reserved from appointeeship to furnish new flat to higher standard than might normally be expected |

The formulation of realistic environmental targets

Once an environmental analysis has been completed it is necessary to put the environmental needs into order of importance and merge the patient’s and therapist’s lists in a realistic way. Some desired outcomes have to be rejected immediately, even when they are considered to be highly relevant and important. Thus, for example, in central London it would be unreasonable to expect the patient to be accommodated in a quiet detached house completely free of noise pollution or for a homeless indigent patient to be provided with an unearned income of £30 000 a year. However, this part of nidotherapy needs to be pursued in an open spirit, as apparently unattainable goals can sometimes be achieved with sufficient determination.

Case example: formulating environmental targets

The patient described in Table 1 has a recurrent psychotic disorder and a history of non-adherence to treatment regimens (no other clinical information is given here to protect his identity). The environmental needs he presented (in no particular order) concern the common areas of comfort, finance, leisure activities and social contacts. Some of these are clearly objective environmental requirements. Others, such as the desire for improved self-esteem, might be regarded more as personal needs related to attitudes and thoughts and best dealt with by problem-solving or cognitive–behavioural interventions. However, the only question to be asked is ‘can this problem be addressed by an environmental change?’. If it can, then it is appropriate for nidotherapy. Each of these needs was considered by his carers and nidotherapist and, despite some reservations, all were regarded as sufficiently important to try to change them.

In examining the process of nidotherapy in this example, I will describe two of these environmental areas and what was involved in their change. The first is the management of the patient’s finances through appointeeship. You may think that this is such a common exercise with those who show poor budgetary control that it cannot be looked upon as a new approach. However, the pathway to appointeeship in nidotherapy is usually different from that in other types of practice. The patient wanted environmental change but could not achieve it because of poor financial control. When asked for ways of, for example, making his flat a more inviting place when his friends visited, all options required more money for furnishings and design, and it was the patient who initiated the discussions about appointeeship by asking for help to use his income more wisely. Use of this approach also helped his self-esteem when his flat became more welcoming.

The leisure activity of staying out late at night drinking caffeine-containing drinks (never alcohol) is also not usually addressed in normal practice, except in a peremptory way under ‘cultural needs’ in care programme review meetings. Nidotherapy established that this social contact, regarded by the clinical team as a relatively insignificant part of the patient’s daily routine (Table 1), was of fundamental importance and needed fostering. In discussing the eventual placement of the patient (part of the answers to the ‘comfort’ component of the environmental analysis) the need to be close to the late-night drinking area was recognised as being very important and it featured high on the list of essentials. Eventually a new flat was obtained less than a kilometre away from the cafés.

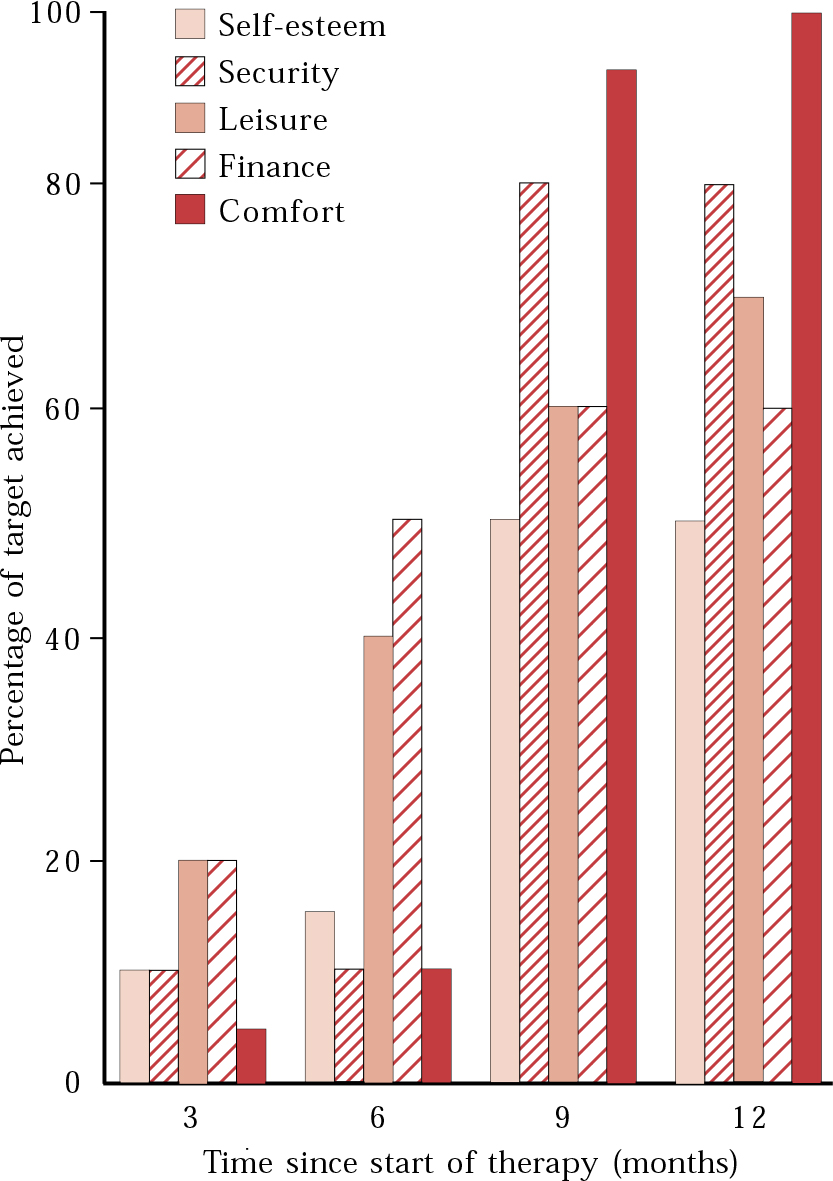

It is often useful, but not essential, to quantify the progress made towards achieving the environmental goals set by patient and therapist. Our patient’s progress in achieving each of the targets over a period of 1 year is shown in Fig. 1. One advantage of this system is that when one target stubbornly remains below the rest in terms of achievement it is recognised and can be separately addressed. Thus, the value of appointeeship and relocation have helped the patient in some respects but he still has limited self-esteem and some uncertainty about his status.

Fig. 1 Progress towards targets outlined in Table 1 over 12-month period (these targets, and the extent to which they were achieved, were agreed jointly by therapist and patient).

The improvement of social function

Nidotherapy could be regarded as a misnomer in that the therapeutic endeavour is indirect. There is no specific attempt to change the person in any way but, by changing the environment, improvement may take place secondarily. However, the primary improvement should be in social functioning. Social function is a direct measure of the fit between person and environment, and even if psychiatric symptomatology remains unchanged, better adjustment of the environment should lead to improved social functioning.

It is perhaps not surprising that the elements of good social functioning – ability to cope with tasks with adequate performance and little perceived stress, good financial management, secure and settled relationships with friends, family and wider society, and enjoyment of spare time (Reference Remington and TyrerRemington & Tyrer, 1979; Reference Weissman and BothwellWeissman & Bothwell, 1979) – often figure so highly in the environmental needs of patients in nidotherapy. It is even less surprising, therefore, that when they are solved or alleviated social function improves. However, the converse is important too. When a nidotherapy programme fails to lead to improved social function the environmental targets need to be re-examined. They may have been inappropriately chosen, or circumstances may have changed so that some or all are no longer appropriate.

Personal adaptation and control

The notion that the patient is in control of a nidotherapy programme, particularly when the patient has a severe psychotic illness or lacks capacity, may at first seem strange. But there are good reasons for it (Box 2). By constantly going back to a plan that has been devised with the patient at its core, the errors that are so common if senior figures in authority decide, without proper consultation, what is best for others are avoided. Even when a disability is pronounced and there may be doubts about the patient’s capacity to contribute to solutions for care (as, for example, in chronic schizophrenia with very little motivation, severe learning disability or dementia), it is important to at least try to gauge the person’s wishes no matter how difficult this task becomes or how apparently inappropriate the responses.

Box 2 Reasons for personal control in nidotherapy

-

• To prevent patronising and paternalistic decisions

-

• To ensure that any environmental change is more likely to be maintained after treatment

-

• To avoid clinicians taking control of matters that are very personal to the patient

Thus, the wish of someone with a severe learning disability to have a certain carer (or type of care) involved with their daily life cannot be roughly cast aside in favour of something different without proper inquiry. Similarly, a recurrent sex offender who asks to be kept in secure institutional care because he feels he is no longer capable of adequate control of all aspects of his life, not just his sex drive, should not be bundled onto a complex treatment programme allegedly to change something that, in his judgement, will remain for ever unchanged.

It is also important to note that nidotherapy can still be appropriate in the management of less severe forms of mental illness than those described here, where the options of controlled environmental change to a great extent need to be coordinated by health professionals. Chronic stress in those whose lifestyle is often the cause of their difficulties can also be approached by systematically tackling environmental needs rather than by changing symptoms (Reference TyrerTyrer, 2003).

Wider environmental integration and arbitrage

The main aim in nidotherapy is to get a good personal fit between individual and environment. However, this cannot be done in isolation and has to take account of wider environmental needs, including those of society. For example, it may suit an individual to have loud music playing all day in his flat because this suppresses the impact of auditory hallucinations, but if it creates great distress for neighbours it would be counterproductive. It is therefore quite common for the patient’s and therapist’s environmental analysis to be discordant and one of the key tasks in nidotherapy is to match up these lists in a way that is acceptable to both patient and therapist. Because this can be particularly contentious it is often necessary to have an arbiter whose authority is respected by both patient and therapist (or clinical team), so that any judgement the arbiter makes will be accepted by both parties. The phase of arbitrage is therefore often an important one in nidotherapy, and early in the treatment plan it is useful to identify a potential arbiter who will be acceptable to all involved in the programme.

The arbiter

The arbiter may be a relative, another independent professional, a friend or a carer. The important prerequisite is that he or she must be trusted by both patient and therapist and given authority to make decisions that will be accepted by all other parties.

The arbiter is needed at the time of matching the two sections of the environmental analysis (Table 1) if it is impossible to reach agreement on views that appear to be opposing. This can be a particularly sticky phase in a nidotherapy programme as, without an active and trusted arbiter, the opposing views of which environmental changes are needed can cause an impasse.

Phases of nidotherapy

Nidotherapy can be given in a formalised manner (usually over 10 sessions in our current work), but it can clearly be invoked at any time in the management of a patient. In formal treatment we currently adopt the following five-phase approach (Box 3).

Box 3 Phases of nidotherapy

-

• Identification of the boundaries of the therapy (i.e. the border between personal and environmental change)

-

• Full environmental analysis

-

• Implementation of common nidopathway

-

• Monitoring of progress

-

• Resetting of nidopathway and completion

Phase I: Identification of the boundaries of nidotherapy

Nidotherapy is usually chosen for a patient who has been treated extensively and has achieved all the gains that are possible from the range of interventions available. In some instances these gains may be very low indeed; in others they may be substantial but with considerable residual disability. In many patients suitable for nidotherapy there has been a long battle between therapists wishing to try interventions and patients desperate to resist them.

The nidotherapist, in introducing the treatment to the patient, emphasises that there is no intention to change the patient and that the whole focus of treatment is on examining the environment to see what environmental changes are most suited. In this early stage of treatment there is often a gratifying improvement in collaboration and communication with the patient. After years of being battered by demands to partake in an intervention that is regarded as of no value, it is a welcome change for the patient to have his or her disability acknowledged more formally and, instead of being required to change the disability, to participate in changing the environment. This acceptance, which could be regarded as validation of disability, allows further treatment to be pursued along a consensual pathway.

By defining what can be given for the disorder and what can be done to change the environment there is less chance of conflict and a greater chance that collaboration will be established for other interventions such as drug treatment (Reference Tasman, Riba and SilkTasman et al, 2000).

Phase 2: Full environmental analysis

This is carried out as described in the case example above. All aspects of the patient’s wishes are noted, for even if they are subsequently discarded as fanciful or unattainable they can still be of value. It is often necessary to visit the patient at home or in other environments, and it is essential to embrace the ideas behind collateral collocation, so that presumptive conclusions are not reached (Box 4).

Box 4 Things that go bump in the night

A man with paranoia complained to his community psychiatric nurse that he could hear everything going on in the flat next door and that a large machine was being moved in the middle of the night. He was shown to be correct when it was found that the flat next door was being used as business premises and the machine being moved was a photocopier.

The therapist’s environmental analysis follows that of the patient and is informed by it. It can be done with the patient or independently, but it is unlikely exactly to mirror the patient’s. Once completed, the sometimes difficult task of joining the two in an agreed way has to be tackled. This is when the involvement of an arbiter may be necessary (Boxes 5 and 6).

Box 5 The arbiter at work

In the case of the noisy neighbour described in Box 4, the patient’s proposed solution was to move to a quieter house. The community mental health team thought this impossible, as noise is so endemic in central London. An agreed member of the clinical team was chosen as arbiter to represent the patient in negotiations in which other methods of noise reduction were pursued.

Box 6 Successful arbitration

A long-stay in-patient with schizophrenia had repeatedly failed in supported accommodation but still wanted the opportunity to live independently. Her arbiter, a voluntary worker, decided that she should be granted at least one attempt to live in an independent flat before abandoning this option altogether. This recommendation was made after the nidotherapist had supported independent accommodation but the clinical team regarded it as not viable.

It is good to report that, after 2 years, the patient is still living in her independent accommodation and is appreciating the extra space and liberty this gives her.

Phase 3: Implementation of a common route (the nidopathway)

Phase 2 may take several hours to complete, but if it is done successfully the next phases will be negotiated much more quickly. The different elements of the nidopathway are identified and each is planned. Obviously, many will need very careful thought and will have to take place in clearly defined steps (e.g. moving to new accommodation). An appropriate timescale for these changes needs to be set to avoid disappointment later.

Phase 4: Monitoring of progress

The phase of monitoring is not an onerous one for the nidotherapist, as although it often takes considerable time to achieve the targets, they should remain clear, with a transparent procedure for completing them. This transparency is important to the patients; full feedback on the progress towards achieving targets emphasises that they have not been forgotten, and they can often offer useful ideas on how to overcome barriers. Despite this, it is highly unlikely that all targets will be achieved successfully (e.g. see Fig. 1). Whether or not further efforts are made to finish the task depends on the patient and the degree of improvement in sociaI functioning that has been attained.

Phase 5: Resetting the nidopathway

There may be times when targets thought to be appropriate and attainable turn out not to be. In these instances it is necessary to return and revise the pathway with different targets, usually less ambitious, but sometimes more so. In this task the role of the patient is very important, as their agreement to what is decided has to be genuine.

How does nidotherapy fit in with other treatment?

Nidotherapy as a treatment package involves the five-phase approach outlined above, but the actual therapeutic input is extremely variable. It is governed by the physical and social environment of the patient and may range from purely structural change (e.g. installation of a boiler) to measures to assist socialising (e.g. enrolment in clubs) or even long-term goals like moving to alternative accommodation.

Most clients receive other treatments during the course of nidotherapy. The important questions are whether nidotherapy fits in with existing treatments and whether it offers any additional therapeutic gain(s) for the patient beyond those of just achieving a better environmental fit.

We believe it does. To begin with, nidotherapy concentrates on ‘environment change’ rather than ‘patient change’. This has a major bearing on the pace of the therapy and also on the parameters used to judge improvement. However, this does not imply that it is mutually exclusive and unaffected by other treatments. For instance, an individual may be less depressed after a course of cognitive–behavioural therapy and this would affect the way she perceives her environment. The time at which nidotherapy is chosen in treatment is critical; it should be selected only for those aspects of symptoms or behaviour that are stable and unlikely to change in the short-term.

Nidotherapy may work synchronously with existing therapies but at the same time remain independent of them. Helping the patient to focus on an environmental change might enhance adaptation to the outside world. This may manifest as better engagement or positive outcomes with other treatments. The targets set and the adjustments made to incorporate changes would be part and parcel of the nidotherapy, irrespective of the progress made with other therapies.

Who should practise nidotherapy?

Many psychiatrists reading this would regard most of the tasks described here as sufficiently basic as to be deskilling, in that they do not require any of the special skills necessary for consultant practice. Some, however, would welcome the fresh approach to engaging with the ‘difficult’ patients, especially when conventional approaches and therapies have failed. Focusing on a goal that is literally more ‘close to home’ for the patient may enhance the therapeutic relationship and help in the delivery of care.

The targets set during nidotherapy often encroach on the arena of other members of the multidisciplinary team, such as the social worker, psychologist, occupational therapist, creative therapist and support worker. We have worked with many disciplines and have found, for example, that music therapy or structured occupational therapy are particularly well placed to help many individuals, not only through any direct effects, but by altering environmental needs that can then be addressed separately. One could well argue that each discipline has the necessary skills and expertise required to work towards one or more goals of nidotherapy, and these can be harnessed as required. The question is not who is best suited to practise nidotherapy but when is it needed?

From a patient’s perspective, a nidotherapist detached from the clinical team could be viewed as ‘neutral’ in the event of a stormy therapeutic relationship – and these are common in those who have persistent disability and an alternative view of the world from their carers. A separate, consistent and collaborative environmental therapy may serve as an anchor for patients drifting between opposition and despair when receiving other unwanted treatments. As mental illness is often chronic and enduring, the focus on working towards a stable and healthy environment may offer a ray of hope.

We have generally found that a nidotherapist separate from the clinical team, but working closely with it, is the best solution. This individual can enhance communication and bridge the gap between the clinicians and the patient. The nidotherapist works as a special type of patient’s advocate, but still within the realms of a therapeutic setting, allowing nidotherapy to proceed in parallel with other forms of care without coming into conflict with them.

We are in the process of manualising nidotherapy for wider use in clinical teams and would appreciate feedback from colleagues who would like to try this approach for themselves. For those patients for whom it seems necessary to ‘go that extra mile’ nidotherapy may be a suitable signpost.

MCQs

-

1 Patients with the following psychiatric diagnoses may be suitable for nidotherapy:

-

a acute stress reactions

-

b paranoid schizophrenia

-

c borderline personality disorder

-

d post-concussional syndrome

-

e Asperger syndrome.

-

-

2 The following are essential elements of nidotherapy:

-

a the patient makes all the important decisions

-

b improving function is more important than removal of symptoms

-

c consensual management

-

d environmental analysis

-

e effecting long-term personality change.

-

-

3 Targets in nidotherapy :

-

a include improving the therapeutic alliance

-

b are decided by the therapist

-

c are environmental

-

d have to entirely achievable

-

e should not normally be changed.

-

-

4 Nidotherapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy are similar in that they:

-

a correct dysfunctional thoughts

-

b can be problem-solving

-

c are collaborative approaches

-

d are better for acute psychiatric disorders

-

e set clear targets.

-

-

5 The skills necessary for a good nidotherapist include:

-

a empathy

-

b diagnostic acumen

-

c flexibility

-

d authority

-

e cultural awareness.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | T | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.