Women's representation in the executive has been gaining attention among gender scholars, increasingly catching up with the much more established field of women's legislative representation. Consequently, we have developed a much better understanding of the factors influencing gender representation in the executive and the ways in which women's representation in the executive relates to women's legislative representation. This study aims to expand these scholarly achievements to a relatively understudied region. We examine women's representation in the executive in five southeastern European countries: Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia.

Our goal is twofold. First, we want to examine the patterns of women's representation in the executive across countries, across time, and across parties. Using an original data set of gendered cabinet appointments for the period from 1990 to 2018, we ask (1) how many women are in each cabinet, (2) what portfolios they occupy, (3) what parties appoint them, and (4) what changes in these variables occur over time. Second, we are interested in whether the patterns and findings from studies of other regions of the world hold true for our sample of countries. Namely, we consider (1) whether an increase in women's legislative representation is linked to an increase in women's representation in the executive, (2) whether left-leaning governments are more likely to appoint female ministers, and (3) whether women's representation in the executive is likely to increase over time.

While we observe a similar pattern of growing women's representation in the executive over time, we find that compared with other European countries, the number of female ministers in southeastern Europe is relatively small. Moreover, our findings indicate divergent patterns when it comes to the link between legislative and executive representation and the link between party ideology and female ministerial appointments. In particular, we find that increased women's representation in parliament does not necessarily translate into increased women's representation in the executive: the countries with the lowest percentages of women in parliament from the sample have the highest percentages of women in the executive. We also find that right-leaning governments tend to appoint women to high-prestige portfolios more than left-leaning governments. Such findings prove that examining southeastern European countries not only leads to a larger sample size but also promises to improve and refine our understanding and theorization of gender representation, broadly speaking, and of gender representation in the executive in particular.

The article proceeds as follows: The next section reviews the literature on women in the executive and derives research questions which guide the rest of the research. The second section situates Eastern Europe in the debate and provides a brief political overview of the countries. The third section presents the empirical data, analyzes it against the research questions, and discusses the results. The final section summarizes the findings and discusses their implications for future work.

WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP, WOMEN IN THE EXECUTIVE

While the participation of women in politics has received significant attention in the last two decades, the same cannot be said about women in the executive. The literature on women's legislative representation has greatly developed (Caul Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006; Krook Reference Krook2006; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009), expanding our knowledge beyond the level and determinants of gender equality in legislatures to consider who is elected to represent women and in what ways they represent women (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006; Celis Reference Celis2006). Moreover, studies of female participation in parliament have covered most regions of the world (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2001; Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova and Zankina2013; Shalaby Reference Shalaby2016). By contrast, and despite the important role of cabinets in defining the legislative agenda (especially in parliamentary systems), women's cabinet appointments remain relatively understudied. Although scholarship has progressed significantly in studying the factors that affect female cabinet appointments from a comparative perspective (Claveria Reference Claveria2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005, Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016; Jacob, Scherpereel, and Adams Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000), we have few systematic examinations of women's ministerial appointments, their responsibilities, and their career trajectories in some countries and regions of the world (Davis Reference Davis1997; Russell and DeLancey Reference Russell and DeLancey2002). The problem is especially conspicuous for the new democracies of southeastern Europe, where we know relatively little about women's leadership.

As Studlar and Moncrief (Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999) point out, the problem of having so little written on women ministers in comparison with women's representation more generally is likely rooted in the small number of women found in any individual cabinet, but it is nevertheless an issue that we need to explore further. What ministerial portfolios do women ministers receive in different countries? Do the types of appointments change over time? Are there any country- or region-specific phenomena that may explain a unique finding? For example, Bego's (Reference Bego2014) results show that the ideological stance of the prime minister is not related to the appointment of women to cabinets in her sample of Eastern European states—a very powerful yet unintuitive result compared with studies focused on Western democracies, which find that, historically, left parties appoint more female ministers. Recent studies have questioned this historical trend (Stockemer and Sundstrom Reference Stockemer and Sundstrom2018), showing that left-wing parties are no longer more likely to nominate women to cabinet posts than other party families.

To understand this finding and the dynamics behind it, we need large comparative studies, such as Bauer and Tremblay's (Reference Bauer and Tremblay2011) timely contribution, as well studies with narrower and deeper focus, such as Curtin's (Reference Curtin2008) examination of New Zealand. Furthermore, recent research on substantive representation, particularly in parties with conservative claims (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2014), has opened a new debate about what constitutes women's interests, who represents these interests, and to what extent these politicians represent women. These developments, coupled with the argument that left and right mean different things in Western democracies and in postcommunist societies (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova and Zankina2013; Tavits and Letki Reference Tavits and Letki2009), raise a question about the three-way link between ministerial appointments, party ideology, and political history. We aim to fill this gap and contribute to the study of women ministers empirically, offering answers to the gendered pattern of ministerial appointments and the importance and prestige of portfolios allocated to women, the role of party ideology in portfolio allocation, and whether and how these have changed over time.

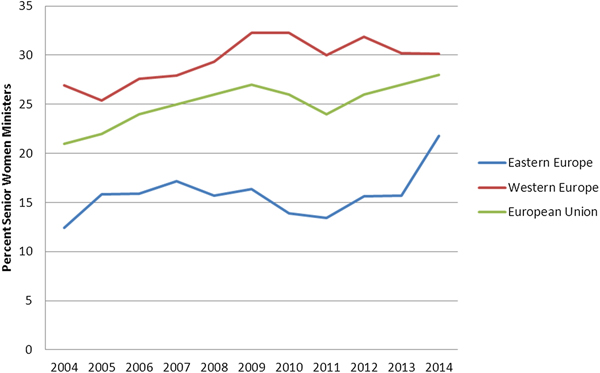

Although women are still underrepresented in all branches of government, the inclusion of women in political institutions has reportedly improved. Siaroff's (Reference Siaroff2000) study of women in cabinets shows variation between 0% and 50% in the share of female appointments in the governments of 18 industrialized democracies in 1998. In a more recent study, Bauer and Tremblay (Reference Bauer and Tremblay2011) report that women's presence in cabinets across the world rose from 9% to almost 17% in the period between 1999 and 2010. Data from the Robert Schuman Foundation provide a snapshot of the descriptive representation of women ministers in the EU-28 (the 28 member states of the European Union [EU]) as of 2014, revealing that the highest inclusion of women in the cabinet went beyond parity in Sweden (the 2010 government included 13 female ministers out of a total of 24) and was less than 0.5% shy of parity in France (the 2012 government had 10 female ministers out of a total of 21).Footnote 1 The average for all 28 member states was 26.59%; however, until recently, few Eastern European cabinets had met this benchmark. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of women ministers in senior positions, comparing Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and the EU. Despite the data capturing a period of 10 years, it is clear that there are far fewer women appointed to ministerial posts in Eastern Europe than in either Western Europe or the EU (keeping in mind that the EU averages include eight Eastern European countries for the 2004–06 period and 10 Eastern European countries for the 2007–14 period).

Figure 1. Percentage of women in senior ministerial positions in Europe. Senior ministers are defined as members of the government who have a seat on the cabinet or council of ministers. Source: European Commission Gender in Decision-Making Database, http://ec.europa.eu/justice/gender-equality/gender-decision-making/database/politics/national-governments/index_en.htm.

Such findings lead us to expect that the proportion of female minister appointments in southeastern Europe will be lower on average than that in the EU and Western Europe. At the same time, recent trends show a notable improvement, including, as of 2018, cabinets in Albania, Slovenia, and Romania, where female ministers make up 46.7%, 43.8%, and 34.6% of cabinet positions, respectively. Hence, examining and understanding changes over time is imperative.

In addition to the number of women who are appointed to government, we are interested in knowing what positions they are appointed to. The gendered division of cabinet portfolios is a subject discussed extensively not only in the academic literature but also in real-life political discourse. Jalalzai and Krook stipulate that “norms of gender have traditionally prescribed distinct roles in society for the two sexes: men have been given primary responsibility for affairs in the public sphere, like politics and the economy, while women have been assigned a central position in the private sphere, namely the home and the family,” and although “it has been muted over time, this divide continues to manifest itself to the present day, albeit in different ways across cultural contexts” (Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010, 6). A recent study by Barnes and O'Brien (2018) highlights the importance of traditional beliefs and the gendered division of portfolios in a comparative study of female defense ministers. Research examining women's legislative representation in the Balkans argues that the traditional divide of professions into male and female is still prevalent in the region (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova and Zankina2013). The latter finding is confirmed in an interview by a well-known Bulgarian member of parliament and political scientist who commented on the leadership race for one of the major Bulgarian political parties. In relation to a female candidacy for the leadership of the Bulgarian Socialist Party, Tatyana Burudzhieva commented, “Unfortunately, politics [in Bulgaria] remains a male profession; the very fact that we are asking whether a woman can take up the leadership post is evidence for the existing inequality.”Footnote 2 Many of the extant studies of women in cabinets reiterate that when women enter high-level politics, they are indeed assigned more often to portfolios with less political importance (see Jacob, Scherpereel, and Adams Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014 for a global analysis of the effect of gender norms; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Moon and Fountain Reference Moon and Fountain1997; Studlar and Moncrief Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999; Tremblay and Stockemer Reference Tremblay and Stockemer2013). Based on this discussion, we expect to find that female ministers are more often assigned to traditionally “women's ministries” or ministries with lower political prestige.

Besides seeking to map the distribution of women in southeastern ministries, we are interested in understanding trends over time, particularly changes in the range and importance of appointments. Consider, for example, the recent appointments of female prime ministers in Romania and Serbia, which can support the argument that the range and importance of portfolios tend to increase over time. In their study of women ministers in Canadian provinces between 1976 and 1997, Studlar and Moncrief (Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999, 387) note that as feminist principles of equality became more widespread, the number of women in cabinets increased and the portfolios to which they were assigned became more diverse. Similarly, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson (Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005, 840) show that the diffusion of international norms has had a positive effect on the number of female ministers in Latin America and that “women are more likely to receive high-prestige posts now, than they were in the past.” The latter finding is challenged by Tremblay and Stockemer (Reference Tremblay and Stockemer2013), who use a larger and newer data set to claim that the portfolios held by women remained largely restricted to the sociocultural and socioeconomic realms. Time periods are also taken into account by Claveria (Reference Claveria2014), who argues that the effect of various political variables such as the adoption of gender quotas by the governing party or the percentage of women in governments is not uniform over time.

In general, research on women's representation, both in the legislature and in the cabinet, assumes that perceptions of gender equality, as well as the adoption of rules, are more favorable to women as time passes. Reynolds (Reference Reynolds1999) and Rashkova (Reference Rashkova2013) show that the period since the first woman was elected to office has a significant effect on the appointment of women to cabinet positions. Therefore, we examine whether there is a change in the type and prestige of ministerial portfolios allocated to women in southeastern European governments. We ask whether the range (the spread of portfolios) and the magnitude (the prestige of portfolios) of female cabinet appointments have increased over time. Are we likely to see women appointed to a wider range of ministries as time passes and to ministries with higher political prestige?

One of the most frequently found explanatory factors for the proportion of women in cabinets is the political ideology of the appointing party. The general expectation is that political parties with left or socialist ideologies appoint more women, as these parties are seen to be “closer” to women's issues. Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson (Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005), for example, show that left presidents are associated with a higher proportion of women in Latin American cabinets. Similar results are also found in Siaroff (Reference Siaroff2000) and Claveria (Reference Claveria2014), who survey the determinants of the appointment of women to cabinets in advanced industrial democracies. The claim that the left is a significant factor in increasing women's proportion in political involvement does not come without its opponents. In an edited volume, Childs and Celis (2014) show evidence from several world regions that despite the conventional wisdom, more and more often, women's issues are represented by conservative claims. Bego's (Reference Bego2014) examination of the determinants of female ministerial appointments in Eastern Europe does not find support for the importance of left ideology either. Research on Bulgaria (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova, Zankina, Celis and Childs2014), on the other hand, shows that while there are more female politicians from the main left political party, right-leaning parties have appointed women to more meaningful political posts.Footnote 3 Stockemer and Sundstrom (Reference Stockemer and Sundstrom2018), in turn, find that change in government, regardless of party ideology, benefits the nomination of women to cabinet posts.

Building on these studies, we pose two questions about the role of political ideology in female ministerial appointments in southeastern Europe: Do governments in which the party with a mandate has a left ideology appoint more women ministers? And do governments in which the party with a mandate has a non-left ideology assign women to more prestigious ministerial portfolios?

EASTERN EUROPE AND THE REALITY OF WOMEN IN POWER

The status of women in southeastern Europe is a function of democratization processes and transition trajectories, as well as ingrained cultures and historical legacies. Women's activism in southeastern Europe dates back to the late nineteenth century, when it was primarily an elitist movement of educated and upper-class women who advocated for rights to education and work. Political rights also figured in these early agendas, though it was not until after World War II that all the countries in the region enfranchised women. With the establishment of communist regimes across the region, women's emancipation became official state policy. The so-called socialist emancipation project aimed to integrate women into the labor force through the introduction of mandatory full employment, access to education, maternity provisions, medical and child care services, laundry facilities, and more. The advent of communist women's organizations and the institution of gender quotas with a target of 30%, in turn, were intended to engage women in political life. Indeed, the proportion of women in politics steadily increased, with some countries reaching more than 25% of women in parliament by the 1980s (Forest Reference Forest2011, 4). For the first time, women entered executive positions. Between 1945 and 1950, a total of 11 women were appointed as ministers in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, the Slovenian and Croatian Republics of Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Republic of Estonia. No women had achieved such a position before 1945 (Forest Reference Forest2011, 3).

At the same time, socialist emancipation policies were viewed as “state feminism” or “feminism from above” (Gaber Reference Gaber, Ballington and Binda2005) and came to be detested for their forced character and ulterior motives of achieving economic and demographic targets (Harvey Reference Harvey2002, 30). Moreover, women's engagement was limited to lower- and local-level positions. And while rubber-stamp parliaments with no real power welcomed female representatives, women were hardly present in supreme party bodies.

The collapse of communism proved disastrous to gender equality and women's political engagement. The forced emancipation resulted in a backlash that translated into an aversion to political mobilization and affirmative action for women. There was an immediate abolition of socialist-era quotas and a sharp drop in the parliamentary representation of women across the region. Former Yugoslav countries faced an additional challenge as rising nationalism in the late 1980s split the Yugoslav feminist movement (Zarkov Reference Zarkov2003). The “sisterhood” divided into Croatian, Serbian, and Bosnian women, on the one hand, and into antiwar and patriotic feminists on the other. Ethnic conflict and war “did not provide much room for deliberations on questions of gender equality or the political representation of women” (Gaber Reference Gaber, Ballington and Binda2005, 24). It reinforced and polarized traditional gender roles with the dichotomous rhetoric of the “man-warrior” and the “woman-mother.”

There is great variety in the representation and status of women today among the five countries examined here. Bulgaria was the first to enfranchise women but remains the only one without any quotas today. While there are constitutional clauses on nondiscrimination, there is no gender-specific legislation. The short-lived Bulgarian Women's Party participated in elections from 1997 to 2005 and was even part of the 2001–05 governing coalition, but since then it has been unable to collect the necessary signatures for registration. Its platform explicitly states that it is a nonfeminist organization that promotes family values. On the other hand, several of the major parties have women's organizations, and women's representation in parliament has been increasing, reaching 23.8% in the 2017 parliament. Furthermore, Bulgaria has had one interim female prime minister and three female vice presidents, including the first ever vice president elected after the establishment of the presidential institution in 1991—a largely symbolic function given the fact that Bulgaria is a parliamentary republic.

Romania has a 2002 law on equality among men and women. There are no legislative quotas, but the two main parties, the Social Democratic Party and the Democratic Party, adopted voluntary quotas of 30% in 2001 that, arguably, are not strictly enforced (Turcu Reference Turcu2009). While there is no women's party, some parties have active women's organizations, such as the National Liberal Party's Organization of Liberal Women in Romania. Romania has the lowest representation of women in the legislature among the five countries examined here, reaching 20.7% for the lower chamber and 14.0% for the upper (a great improvement over the previous government, which had 13.5% and 7.4%, respectively). A semipresidential republic, Romania's current social democratic government has 34.6% of female ministers and is headed by Romania's first female prime minister.

Currently, all three former Yugoslav countries in our study have list proportional representation systems. Croatia was the first among the three to introduce voluntary party quotas.Footnote 4 In 1996, the Social Democratic Party adopted a 40% quota. During its rule between 2000 and 2003, the legislature adopted a law on gender equality, along with a number of additional laws with gender-friendly clauses. While there are no women's caucuses, the Social Democratic Party has an active women's wing, and in 2004, the Women's Democratic Party was formed. The party declares that it “is not a feminist-based organization and has no support from the Croatian feminist movement.” The number of women reached 23.8% in the 2015 parliament but declined to 18.5% after the 2016 elections. A parliamentary republic with an elected president as head of state, Croatia has had one female prime minister and one female president.

Serbia instituted legislative candidate quotas for the local and national levels in 2002 and 2004, respectively. Since then, the percentage of women in parliament has been steadily growing, reaching 34% in 2016 and ranking 30th in the world.Footnote 5 This is the highest percentage in Eastern Europe. A women's parliamentary club that deals with gender-related issues and the legislature was established in 2013. There is a history of women's political organizations, including the Women's Party, formed after the first multiparty elections in 1990, and the Women's Political Network, formed in 2000. Serbia has not had a female president, but it appointed its first female prime minister in 2017.

Macedonia has also witnessed a steady increase in the parliamentary representation of women as a result of the adoption of quotas. Legislative candidate quotas were adopted at the national level in 2002 and at the local level in 2004. Before legislative quotas, party quotas were instituted by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia, the Liberal Democratic Party, and the Liberal Party. A women's parliamentary club that deals with gender issues and legislative changes in various policy areas was established in 2003. Prior to that, in 1995, the Ministry of Labor and Social Policy created the Unit for the Promotion of Gender Equality. Currently, women constitute 38.3% of parliament, ranking Macedonia first in southeastern Europe and 19th in the world. Macedonia has not had a female prime minister or president and currently has 15.4% female ministers.

CRACKING THE HIGHEST CEILING IN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE

Data and Method

In this article, we set out to map women's representation at the highest echelon of political power—the cabinet. We present data on women ministers in Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia, thus encompassing five southeastern European democracies.Footnote 6 Our sample consists of data collected for the period from 1990 onward, with the exception of Serbia, where the data begin in 2000.Footnote 7 We have collected data on all cabinet members and their portfolio allocations, which allows us to get a detailed overview not only of how many women there are across time but also where these women are placed and how female ministerial appointments have changed over time. Our unit of analysis is the woman minister. This means that if a woman was allocated to two different portfolios, we code the more prestigious one (explanation later) and count this as one observation. We believe that this coding is more precise than counting portfolios, as some previous research works have done (Studlar and Moncrief 1997), because the latter approach inflates the actual number of women present in cabinets. In the case that a woman was assigned as a deputy prime minister but also had a portfolio, we consider her portfolio allocation to be more determinate of her role in the cabinet and therefore code for that. Although the position of deputy prime minister is symbolically important, in our view, the actual power is determined by the portfolio.

Following extant studies of women's descriptive representation in cabinet, we present data on the share of women in the cabinet over time and per country, as well as for the region as a whole. Furthermore, we code the positions held by women according to the level of prestige that each portfolio has and thus are able to show what positions women are appointed to and how these appointments change over time. In addition, we examine the data from а party ideology perspective. Given the different meanings that left and right carry in the postcommunist region (Tavits and Letki Reference Tavits and Letki2009),Footnote 8 we are also interested in the extent to which party ideology plays a role in how many women are included in a given cabinet and where those women are assigned. Considering that our goal is to map women's representation in southeastern European cabinets and compare the patterns with findings from other regions of the world, we find a descriptive approach to presenting and analyzing the data gathered to be most appropriate.

Our data set covers a much understudied region, and it includes three countries from the former Yugoslavia, which have not been present in comparative gender scholarship. Thus, in this first cut through the data, we hope to fill a clearly identified gap in our understanding of women's representation in high politics in the southeastern European region.

Women's Descriptive Representation in Government

Our expectation that the proportion of female minister appointments in southeastern Europe is not on a par overall with the current EU average of 28.5% (European Institute for Gender Equality 2017) holds true for all cases in terms of average percentage. Yet Bulgaria and Romania have reached and surpassed that threshold—Bulgaria with all four governments between 2013 and 2017 (ranging from 30% to 30.3%) and Romania with three of its latest four governments (ranging from 29.6% to 31.2%). Interestingly enough, it is the countries without legislative quotas that have the highest percentages of female ministers. By contrast, the other countries in the sample, which do have legislative quotas, have not reached beyond 25% at any moment. Macedonia, which has the highest percentage of women in parliament, has a significantly lower percentage of women in the executive, with the highest value reaching 15.8%. The average proportion of women ministers in the region for the entire period of study is 13.4%, which is significantly lower than the EU average of well over 20%.Footnote 9 The regional highs are Bulgaria's 2013 government with 35.3% and Romania's current government with 32.1% women. These are outliers that are far ahead of many countries in the EU, yet they remain far below the parity achieved by the Scandinavian countries.

Table 1. Female ministers in postcommunist Bulgaria, 1990–2018

Notes: The cabinets with the lowest and highest proportions of female ministers are presented in bold. Data collected by the authors from the government of Bulgaria (http://www.government.bg), Tashev (Reference Tashev1999), Dnevnik Daily (http://www.dnevnik.bg), and other local media outlets.

Table 2. Female ministers in Croatia, 1990–2018

Notes: The cabinets with the lowest and highest proportions of female ministers are presented in bold. Data collected by the authors from the site of the Croatian government (http://vlada.gov.hr) and the Digital Information and Documentation Agency of Croatia (http://www.digured.hr).

* This government is called “national unity” because it was created to be all-encompassing as a result of the war.

Table 3. Female ministers in post-Yugoslav Macedonia, 1990–2017

Notes: The cabinets with the lowest and highest proportions of female ministers are presented in bold. Data collected by the authors from the government of the Republic of Macedonia (http://www.vlada.mk) and the State Gazette (http://www.slvesnik.com.mk).

Table 4. Female ministers in postcommunist Romania, 1990–2018

Notes: The cabinets with the lowest and highest proportions of female ministers are presented in bold. Data collected by the authors from the site of the Romanian government (http://www.guv.ro) and the Official Gazette of Romania (http://www.monitoruloficial.ro).

Table 5. Female ministers in post-Yugoslav Serbia, 2000–2018

Notes: The cabinets with the lowest and highest proportions of female ministers are presented in bold. Data collected by the authors from the site of the Serbian government (http://www.srbija.gov.rs), governmental archive (http://www.arhiva.srbija.gov.rs/cms/view.php?id=510), and various local media.

Bulgaria represents an interesting case given the lack of gender-friendly legislation or meaningful women's political mobilization. Bulgaria has the highest percentage of female ministerial appointments compared with the other countries examined here, even though the representation of women in parliament (23.8% as of 2017) lags behind Serbia (34.4%) and Macedonia (38.3%) and is just barely above Croatia's 2015 level (23.8%). Romania exhibits a similar pattern, with 20.7% of women in parliament (lower chamber) but 32.1% of women in government, including a female prime minister. Such findings contrast with studies of Western democracies (Claveria 2013) that argue for a positive relationship between women's representation in parliament and in the executive. It may also highlight a case specificity, namely, that women at the highest echelons of power in Bulgaria and Romania are not very likely to identify with and mobilize around gender issues (i.e., a high percentage of women in the executive but a lack of mobilization around women's issues). This may be partly due to fatigue with the communist-era forced emancipation and the strong antifeminist sentiment that ensued (Gaber Reference Gaber, Ballington and Binda2005, 25)—a feature that differentiates postcommunist countries from Western democracies. Previous research on Bulgaria finds an outright distaste for the feminist agenda in Bulgaria (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova, Zankina, Celis and Childs2014). Such specificity calls into question the link between descriptive and substantive representation and the assumption (at least in the southeastern European context) that female politicians act differently in office than their male counterparts and are more likely to promote women's issues. Although the link between descriptive and substantive representation is not the focus of this study, our findings suggest a regional specificity and directions for future research on this point.

Macedonia further challenges the link between women's representation in the legislature and in the executive. It has the highest percentage of women in parliament (38.3%) but the lowest average percentage of women in the executive (10.8%). The highest percentage of women ministers that Macedonia has ever reached is 15.8%, and the highest number of women in a cabinet is four—both significantly below what we see in the other cases. The representation of women in parliament has greatly increased—a direct effect of quotas—whereas the number of women in cabinets has remained at a steady low. In fact, the percentage variation is a function of changing cabinet size (ranging from 18 to 31) rather than a significant change in the number of female ministers. Such findings contradict our expectation that women's presence in the executive is likely to increase with time and call for an explanation of the unusually (compared with other countries in the sample) low number and percentage of women in the top executive. One explanation may be provided by Arriola and Johnson (Reference Arriola and Johnson2014) who argue that the number of women's cabinet appointments is significantly lower in countries where leaders must accommodate a larger number of politicized ethnic groups. Although Croatia and Serbia also experienced ethnic conflict and, unlike Macedonia, even war, the aftermath of the Yugoslav wars left both countries ethnically homogenous—90.4% of ethnic Croats in Croatia and 83.3% of ethnic Serbs in Serbia.Footnote 10 By contrast, ethnic Macedonians constitute less than one-third of the population in Macedonia today, and ethnic Albanians, more than one-quarter.

In all countries, the lowest number of women in cabinets (zero) occurs in the first few years after the transition to democracy. We see that with the exception of Bulgaria (and Serbia, for which the data begin in 2000), all other countries start their democratic periods with 100% male cabinets. And while most countries quickly change this, albeit in small numbers, and begin to include women, Romania set a notorious record by having five of its six first cabinets composed solely of male politicians. Romania is also the country with the lowest percentage of women in parliament in the sample (20.7% in the lower chamber). Contrary to previous suggestions that semipresidential systems are expected to have more women because the greater freedom of the president to appoint individuals from marginalized groups (Bego Reference Bego2014), we find that in Romania, which has a semipresidential system of government, cabinets have been overwhelmingly male. Despite being the only country with a semipresidential system from our sample, Romania has the longest period of entirely male cabinets (1990–92 and 1996–99).

The Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Romanian cases highlight the variation among the five countries, which forces us to consider the differences rather than the similarities in the cultural and historical contexts. The communist legacy, expected to have a dominant effect on the representation of women, does not appear to have a uniform impact. Although it helps explain the initial uniform drop in women's representation after communism, it is of little use in our attempt to understand current variations. Furthermore, we are pushed to consider the “different communisms” rather than “communism”—a less repressive regime in Yugoslavia that allowed for the penetration of feminist ideas but much more repressive regimes that were isolated from the West in Bulgaria and Romania. Ethnic conflict and different histories of women's activism seem to be no less important in shaping the gender balance in politics and accounting for the within-region variation. An entrenched patriarchic culture and Balkan machismo, understood as overt displays of virility (Buchanan Reference Buchanan2002; Simic Reference Simic1969), on the other hand, stop short of explaining such variation but may account for region-wide trends.

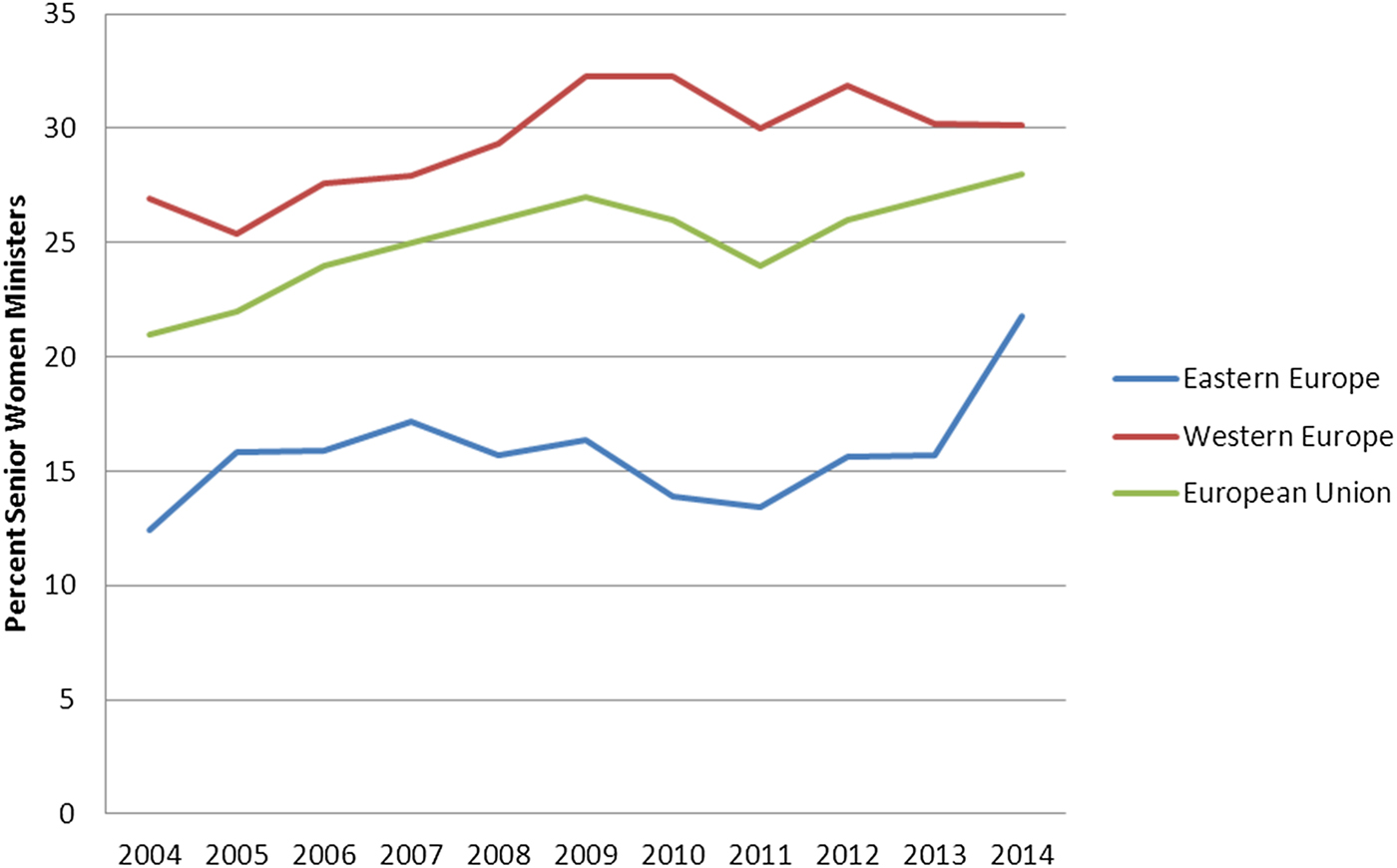

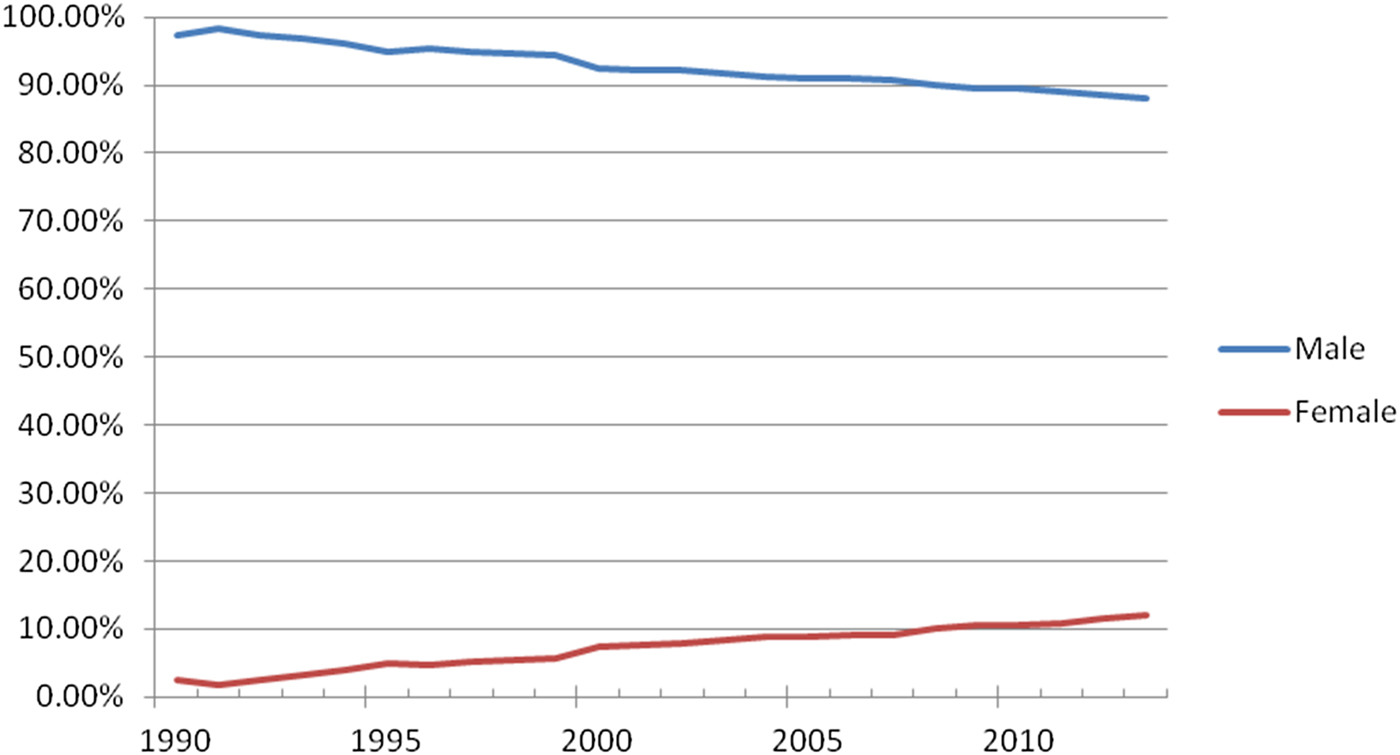

Figure 2 shows the proportion of men versus women cabinet members over time for all studied countries. It is clear that southeastern European cabinets are still to a large extent dominated by men. Two observations stand out in the figure. First, we see the large gap between the number of men and women included in cabinets—while men are at the top of the ladder, comprising more than 85% of the southeastern European cabinets for over two decades now, women are still below 13%. Second, and perhaps a bit more optimistic, is the observation that despite making up a significantly smaller proportion of each cabinet, women's representation has been steadily increasing over time. Starting from less than 2% in 1991, we see the descriptive representation of women in cabinets growing to just shy of 10% by 2008 and climbing to its highest value for the region, 12.01%, at the end of 2013. Such an increase supports the time effect argument, and it may be attributed to the effect of EU norm diffusion. Bego argues that “candidate countries appoint qualified well-educated women to prestigious posts during the accession period to appeal to the EU, but because it is a symbolic action, the effect does not last after membership” (Reference Bego2014, 356). On the contrary, our data show that Bulgaria and Romania have witnessed the highest percentage of female ministers since accession. While it is too early to draw any conclusions about Croatia (given its very recent EU membership), the current trend looks promising.

Figure 2. Proportion of female versus male ministers in southeastern Europe, 1990–2014. Countries included are Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia. The data used to create this chart are cumulative over the studied period. Source: Data originally collected by the authors.

Women's Status in the Political Hierarchy

Our next question concerns whether female ministers are more often assigned to traditionally “female ministries” or ministries with lower political prestige. To address this question, we divide ministerial portfolios into high-, middle-, and low-prestige portfolios. This categorization is based on extant research (Atchison and Down Reference Atchison and Down2009; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005; Tremblay and Stockemer Reference Tremblay and Stockemer2013) as well as our knowledge of the region and the specific cases. There is a rich debate on the categorization of ministerial portfolios, the role of context-specific factors, and the multiple factors that need to be taken into account. For the purpose of this study, we adopt a unidimensional categorization of portfolio prestige based primarily on Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson (Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005). While we find Krook and O'Brien's (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012) Gender Power Score a more refined measurement of actual power, we are hereby limiting ourselves to a distinction based on prestige and omitting the additional dimension of masculine versus feminine portfolios. For the purpose of this study, high-prestige ministries include all the power ministries (Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Defense) as well the positions that yield great power such as prime minister and finance minister—all traditionally reserved for men. As Atchison and Down (Reference Atchison and Down2009, 6) point out, portfolio allocation has been used as a way of excluding women from the highest political offices and reserving the most prestigious offices of the state (Defense, Foreign Affairs, Finance, etc.) for the “first sex.” Low-prestige portfolios, in turn, include the socioeconomic and sociocultural ministerial posts (Health, Education/Science, Culture, Labor/Social Affairs/Social Dialogue/Family, Sport, Tourism, and Transport) as well as newer or country-specific ministries (Environment/Water, Forests, and Fisheries, Veterans’ Affairs/Religion, etc.) and ministers without portfolios. As already pointed out, extant research shows that women are found to be more likely to occupy such ministries. Lastly, the medium-prestige portfolios include Economy/Public Finance/Information, Justice, EU, Public Administration, Regional Affairs, and Agriculture. Those ministries are not as powerful as the high-prestige ones but, given the context of democratic transition and European integration, yield significant power.

When evaluating the portfolio distribution, we need to keep in mind the number of portfolios in each category—five high-prestige portfolios, nine middle-prestige portfolios, and 13 low-prestige portfolios. Hence, every cabinet in our sample has more low-prestige portfolios regardless of whether they are occupied by men or women, which skews the data in that direction. We have applied the same categories to all five cases, as opposed to the country-specific portfolio categorization done in other studies (Druckman and Roberts Reference Druckman and Roberts2008). The rationale for such an approach is that despite regional variations, the five countries share cultural characteristics and common gender perceptions and stereotypes, including what constitutes a “man's job.”

Our data indicate that women are more likely to occupy low-prestige ministries in all countries except Macedonia. More than 60% of the female ministers in Serbia, 50% in Bulgaria, and 57% in Croatia have occupied low-prestige ministries or the so-called traditional women's portfolios in the education, environment, and social sectors (see Table 7). Romania sets a notorious record of having close to three-quarters of its female ministers in the low-prestige category. Macedonia is a surprising exception with the fewest female ministers for the time period, but two-thirds of them are in the high- and medium-prestige categories. Perhaps the overall low numbers of female ministers in Macedonia, in combination with external pressure, may explain this finding. Going back to Bego's (Reference Bego2014, 356) argument that domestic leaders often appoint women to government positions in order to gain more legitimacy and leverage with international organizations, we can argue that Macedonia has few female ministers, but they are strategically positioned in highly visible positions.

We further set out to examine the time effect on the range and magnitude of female cabinet appointments. We expected to see women appointed to a wider range of ministries as time passes and to ministries with higher prestige. To address this question, we divided the time span of the study into three periods—an approach also adopted in Tremblay and Stockemer (Reference Tremblay and Stockemer2013). For Bulgaria and Romania, those are (1) 1990–96—a time of political turmoil and economic uncertainty for both countries, dominated by the former communist elites; (2) 1997–2003—a definitive turn toward reform and orientation toward the Euro-Atlantic structures; and (3) 2004 to the present—2004 marking the year of NATO membership for both countries and the closure of all the chapters of the EU's acquis communitaire. The time periods for the other three countries differ, largely because of the ethnic conflicts experienced by the countries of the former Yugoslavia and the considerable setback in their political and economic development caused thereby. Furthermore, the categories are more of an approximation than distinct periods due to the divergent trajectories of development. The time periods are (1) 1990–99—a time of war and ethnic nationalism both for Croatia and Serbia (although Serbia figures in the study after 2000 because of several instances of reorganization and redrawing of its borders) and a rise in ethnic tensions for Macedonia; (2) 2000–2007—a period that marks a change of course for all three countries toward reform and away from nationalist politics, as well as a period of increased engagement of the international community (including international peacekeeping missions in Macedonia); (3) 2008 to the present—a period during which Croatia became a member of both NATO and EU, Serbia submitted its official EU application, and Macedonia has progressed with negotiations for candidacy both to NATO and the EU and has been invited for pre-accession negotiations with the EU.

Bulgaria and Romania do indeed show a greater range of portfolios assigned to women, but there is no significant increase in prestige (see Table 6). In both countries, women still occupy mostly low-prestige positions, and the trend has even increased over time. High-prestige positions, in turn, have decreased in percentage, but this is also due to the overall increase in numbers (n = 8 in period one and n = 102 in period threeFootnote 11). The countries of former Yugoslavia show a more promising trend, as illustrated by Table 7. We notice a similar increase in the range of portfolios, but one that is coupled (especially for the last period) with a decrease in low-prestige positions and an increase in medium-prestige positions. Overall, there is a more even distribution among high-, middle-, and low-prestige positions compared with Bulgaria and Romania. In the last period, the majority of women occupy high- or middle-prestige positions, the latter reaching more than one-third of all appointments. We can attribute such improvements in the status of female politicians to international pressure and influence from the EU in particular, legislative initiatives in all three countries (quotas), a history of Western-style feminism, and increased awareness of gender issues. By contrast, Bulgaria and Romania have not experienced Western-style feminism, did not reinstitute gender quotas in the postcommunist period, and continue to exhibit trends observed during the communist era, when women were appointed to lower- and local-level positions.

Table 6. Distribution of portfolios over time for Bulgaria and Romania

Note: Data collected by the authors.

Table 7. Distribution of female portfolios in SEE from 1990-2018*

Note: The category other includes care-taker governments, center or grand coalition governments which cannot be easily classified as right or left in their overall ideology. Data collected by authors.

* Determined by the party affiliation of the prime minister.

We can conclude that while the number and the range of expertise of women in the executive have increased over time, women in southeastern Europe remain low in the political hierarchy—a finding that proves that mentalities are slow to change.

Women's Presence on the Political Spectrum

We next examined the political affiliations of women in the executive, questioning whether governments in which the party with a mandate has a left ideology appoint more women ministers than non-left governments (see Table 8). Data show this to be the case in one of the countries. In Romania, the majority of female ministers have taken part in left-mandated governments, but the average percentage of female ministers is highest in “other” (neither left nor right) governments. This high number of female ministers from left governments is to be expected, as Romania has experienced the longest rule of center-left parties in its postcommunist period, and the Social Democratic Party was the first one to introduce voluntary party quotas. The high percentage of women in “other” governments can be attributed to the overall small number of those governments and the high percentage of female ministers in the 2015–17 independent government.

Table 8. Female ministers in postcommunist southeastern Europe, based on party ideology*

Notes: The category other includes care-taker governments or grand coalition governments, which cannot be easily classified as left or right in their overall ideology. Data collected by the authors.

* Determined by the party affiliation of the prime minister.

In Macedonia, the number of women is evenly split between left and right governments, and the average percentage of female ministers is roughly equal. Croatia is an interesting case with the majority or its female ministers being from right governments yet left governments demonstrating a slightly higher percentage of women in government. This can be explained by the fact that there have been only three left governments out of a total of 14, while several right governments in the early years appointed no women. The variation in the percentage of female ministers is mostly due to the wide range of ministerial positions in each government (ranging from 18 to 34) and not so much to the number of women in each government, which ranges from 0 to 5. Serbia has a higher number and percentage of women in left governments, being the closest to patterns in Western countries. This can be explained by the wave of Western feminism and the effect of the wars, which juxtaposed feminist and nationalist rhetoric.

The most intriguing case in the sample is Bulgaria, which shows a significantly higher number and percentage of female ministers appointed by right governments, questioning the link between left ideology and women's representation.

Our cases show mixed results that do not indicate a region-wide trend. Thus, we conclude that that left ideology is not a strong predictor of female presence in the executive in southeastern Europe.

Lastly, we examine the link between political affiliation and prestige, questioning whether governments in which the party with a mandate has a non-left ideology assign women to more prestigious ministerial portfolios (see Table 9). This is true for two of the cases—Bulgaria and Macedonia, where right governments have assigned three and four women, respectively, to high-prestige positions. In Serbia, there are three women in high-prestige portfolios, split two to one for left and right governments, respectively. Romania has five women in the high-prestige category, four of whom from left governments, which is mostly due to the recent appointment of a female prime minister from the Social Democratic Party. Overall, there is no strong link between left ideology and high-prestige appointments of female ministers. As argued elsewhere (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova, Zankina, Celis and Childs2014), such findings may be explained by the peculiarity of the political spectrum in postcommunist countries, where the left was largely dominated by former communist parties, hence its association with the status quo, whereas the right came to represent change and reform, attracting people with more progressive views and diverse backgrounds. Other explanations may consider party age and recruitment mechanisms. While left parties were for the most part successors of former communist parties, inheriting their structures and recruitment mechanisms, right parties organized after the collapse of communism, having no established recruitment mechanisms or a pool of cadres. Hence, women might have been assigned to more prestigious positions due to the lack of qualified and politically loyal men—an effect we would expect to decrease with party age.

Table 9. Distribution of female portfolios in southeastern Europe, 1990–2018*

Notes: The category other includes care-taker governments and center or grand coalition governments, which cannot be easily classified as left or right in their overall ideology. Data collected by authors.

* Determined by the party affiliation of the prime minister.

CONCLUSION

Our findings give reason for hope: while southeastern Europe exhibits lower percentages of women in the executive, there has been a notable improvement over time. While women in the executive represent a smaller percentage than the 2017 EU average, and they fall even further behind their counterparts in Western European countries, there are more cases reaching and surpassing that average recently. Our data further reveal that women ministers in southeastern Europe continue to occupy primarily low-prestige positions. The distinct background of the examined countries confirms our expectations of overall lower representation of women in southeastern Europe, particularly at the highest echelons of power, greater representation of women in left parties and governments, and an overall increase in political representation, as well as in the range and status of appointments. Some of the positive trends evident from our study are that the number of women in the executive has been growing at a steady rate, and so has the range of portfolios assigned to women.

While women have not managed to “crack the highest ceiling” in large numbers, their presence and role in government have been growing over time. More importantly, women are making headway across the political spectrum, and their avenues to power have not been primarily limited to left parties. In fact, it is right parties that have assigned women to the highest positions of power and those traditionally occupied by men. This may be due to the fact that right political parties are, at least initially, opposition parties that are progressive and stand for change, including on gender issues. They are also new and less institutionalized, which creates a great shortage of qualified cadres and results in a much more random candidate selection process than in the established former communist parties. Paradoxically, this makes for a greater opportunity for well-qualified women who come from the outside and do not have to climb through the rigid and often male-dominated internal party structures. Such a region-specific phenomenon may have lasting implications for the substantive representation of women in the region and beyond. While talking about substantive representation of women may be far-fetched when referring to southeastern Europe, and the best we can argue for is substantive presence (Rashkova and Zankina Reference Rashkova, Zankina, Celis and Childs2014), when substantive claims on behalf of women are made, we should expect they would differ from the familiar rhetoric in Western Europe.

Our examination of women in executive leadership in five southeastern European countries highlights important differences between southeastern Europe and Western Europe. The most striking finding, however, is the within-region variation, which calls for further analysis. Considering additional factors such as party age, changes in cabinet size or EU member/candidate status may provide additional explanations to the observed trends. Linking women executive representation with representation in the legislature and with voting behavior promises to give us a fuller picture of women's political engagement and its impact on women's role in the executive. Furthermore, we would like to delve into the strategic (as opposed to institutional and cultural) factors that influence women's appointments to the executive, that is, the choices of specific politicians to appoint women versus men, and the strategic considerations at the party level to promote women leaders.