Introduction

This study examines whether descriptive representation increases responsiveness by elected officials to constituents of different ethnic groups. We gather information on the ethnic identity of all state legislators in 49 states (excluding Nebraska’s unicameral and nonpartisan legislature) and explore the extent to which legislators are more likely to respond to information requests from members of different ethnic groups. We are especially interested in assessing two related questions: Are white legislators equally responsive to all minority constituents? And are minority legislators as responsive to cominority constituents as they are to coethnic or white constituents? In other words, do the benefits of descriptive representation require a specific match in that minority constituents achieve greater political equality only when they are represented by an elected official who is a member of the same minority group?

While we know a lot about the benefits of descriptive representation within groups (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2007, Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2008; Canon Reference Canon1999; Fenno Reference Fenno2003; Grose Reference Grose2011; Tate Reference Tate2003), we know less about representation between groups. We argue that the growing diversification of the U.S. population warrants a focus on not only the intragroup dynamics of descriptive representation but also an intergroup approach. Instead of looking within minority groups, or comparing each minority group to the white majority in isolation, we can learn by also comparing white legislators’ responsiveness to different minority groups and minority group legislators’ responsiveness to each other.

In contrast to previous studies, our attention is not centered exclusively or mainly on the behavior of white elected officials to constituents of a specific ethnic group or minority constituents as a whole. While Black and Latino citizens share a common status as racial minorities, legislators may not necessarily relate to constituents via this majority–minority cleavage. We focus on legislators’ responsiveness to white, Black, and Latino constituents, reflecting the ways in which legislators may differentially position Black and Latino citizens relative to the white majority.

This study also departs from others that have considered the impact of coethnic and cominority cues on vote choice or on voters’ evaluations of candidates. In this study, voters are the senders of ethnoracial cues and legislators are the receivers; the outcome of interest is the behavior of the latter. While most research on inter- and intra-minority dynamics is based on mass attitudes and behavior, this paper explores the behavior of elites at the state level. This focus is motivated by the importance of multilevel representation for ethnoracial minorities in the American federalist system (Hero Reference Hero1992), whereby state governments in particular play a major role in policymaking and can affect minorities’ levels of representation. State government is also an arena in which ethnoracial minorities have historically exercised greater influence (compared with the national government) and have reached higher levels of representation—both descriptive (i.e., electing more of their members for office) and substantive (i.e., achieving their desired policy outcomes) (Hero Reference Hero1992).

In order to answer the questions elaborated above, we conduct an audit experiment of the 7,276 representatives and senators serving in 49 state legislatures in January 2020. Each legislator with a working email address receives an email (via the email automation software Overloop) from one of three different putative senders: a white, Black, or Latino constituent. For example, a Black legislator might receive a constituency service request from a coethnic (Black), cominority (Latino), or non-coethnic (white) constituent. The ethnorace and name of the sender are randomly assigned at the level of the individual legislator. Footnote 1 The treatment of interest is the ethnoracial cue contained in the text of the email and signaled by the name of the sender. The outcome of interest is whether the legislator responds to the inquiry when the information available to the legislator is the name of the email sender and, if the legislator opens the email, the explicit ethnoracial cue in the body of the message. This design allows us to explore between-legislator variation in responsiveness to constituents of different ethnoracial groups. Such variation is essential to understanding potential biases in whom legislators represent, since responding to constituents’ emails is a basic (yet critical) tool that elected officials use to serve their communities.

In contrast to prior audit experiments (e.g., Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Giulietti, Tonin, and Vlassopoulos Reference Giulietti, Tonin and Vlassopoulos2019; Hannah, Reuning, and Whitesell Reference Hannah, Reuning and Whitesell2023, among others), our findings suggest a lack of legislators’ discrimination, on average, against Black relative to white constituents. Instead, we find that all legislators, on average, respond more to both white and Black constituents relative to Latino constituents. These findings are similar to those of White, Nathan, and Faller (Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015), who—employing a similar experimental design—uncover that Latino voters are less likely to receive any response, and more likely to receive responses of lower quality, from local election officials. For Black constituents, our evidence suggests few benefits to descriptive representation in terms of increased responsiveness to constituency service requests, which stems primarily from the lack of white legislators’ discrimination against Black constituents. For Latino constituents, the evidence suggests greater benefits to descriptive representation: Although not significant, the magnitude of point estimates suggests that Latino legislators respond more to Latino relative to white constituents, and the evidence convincingly suggests that white legislators discriminate against Latino relative to white constituents. We find little evidence of cominority representation by Black legislators for Latino (relative to white) constituents. We do find suggestive evidence for cominority representation by Latino legislators for Black (relative to white) constituents, but there are too few Latino legislators to definitively establish this possibility.

Since the potential benefits of coethnic representation for Latinos are driven primarily by white legislators’ discrimination against Latino relative to white and Black constituents, we then assess heterogeneous effects among specifically white legislators to suggest causal mechanisms that may be at play. We find evidence for intrinsic motivations in light of Republicans’ discrimination against Latino relative to Black constituents, especially since Latinos are much more likely than Black constituents to be copartisans. We find, moreover, that white legislators in racially diverse districts exhibit greater responsiveness to Latino and Black constituents compared to white legislators in less diverse districts. These findings suggest the existence of strategic incentives to appeal to a multiracial coalition. However, it is also possible that legislators from more diverse districts harbor different intrinsic motivations from legislators in less diverse districts.

In the rest of the paper, we first situate the project within the literature on descriptive representation and coethnicity and lay out two broad classes of causal mechanisms (“Theory and Existing Evidence”). In “Experimental Design,” we outline the experimental design, including the sample selection, random assignment of treatment, and identification strategy. This section also includes a description of the intervention and the results of an Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) pretest. “Descriptive Statistics” and “Results” present and interpret the findings, and “Conclusion” concludes.

Theory and Existing Evidence

Descriptive Representation and Coethnicity

Political scientists contend that one way to increase political equality among ethnoracial minority groups is to elect more legislators from those groups (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999, Reference Mansbridge2003; Whitby Reference Whitby1997). Indeed, the presence of Black and Latino elected officials has been found to positively predict participation and the representation of interests for Black and Latino constituencies, respectively (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2007, Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2008; Canon Reference Canon1999; Fenno Reference Fenno2003; Griffin and Newman Reference Griffin and Newman2008; Grose Reference Grose2011; Herring Reference Herring1990; Juenke and Preuhs Reference Juenke and Preuhs2012; Minta Reference Minta2011; Preuhs Reference Preuhs2005, Reference Preuhs2007; Preuhs Reference Preuhs2006; Tate Reference Tate2003). Although party remains a principal driver of political outcomes, these impacts of descriptive representation are above and beyond the role of party. For example, Cobb and Jenkins (Reference Cobb and Jenkins2001) find that Black and white southern legislators in the Republican party during the Reconstruction era differed ideologically on issues related to race and those not related to race. Likewise, scholars have found that Black legislators are more likely than white Democrats to reflect the interests of their Black constituents in roll call votes (Canon Reference Canon1999; Tate Reference Tate2003; Whitby Reference Whitby1997; Whitby and Krause Reference Whitby and Krause2001).

The existing literature largely agrees that Black Americans are better represented by fellow Black Americans than by whites, and Latinos are better represented by fellow Latinos than by whites. However, there is less agreement on whether white legislators differentially respond to Black and Latino constituents relative to white constituents. Similarly, there is disagreement on the quality of representation of minority constituents by legislators of the same vs. different minority groups, relative to representation by white legislators. For example, Griffin and Newman (Reference Griffin and Newman2008) speculate that Latinos may not be much better represented by African-American legislators than by white legislators. Relatedly, Preuhs and Hero (Reference Preuhs and Hero2011) contend that descriptive representatives often make policy decisions from cues that differ between Black and Latino constituencies—cues that cannot be neatly placed along a liberal-conservative continuum, suggesting that the explanatory power of descriptive representation exists beyond that which is due to party alone (Preuhs and Hero Reference Preuhs and Hero2011). Conversely, Minta (Reference Minta2011) argues that, while tension exists in the public between Blacks and Latinos in competition for employment and housing opportunities, this tension does not prevent Black and Latino legislators from working together to support both groups in policymaking.

This disagreement raises important and still unanswered questions. Do white legislators discriminate equally against Black and Latino relative to white constituents? And do the benefits of descriptive representation require a specific match? That is, do minorities achieve greater political equality only when they are represented by a member of the same minority group? Or will any minority do? These are the questions that this paper seeks to answer.

The existing literature points to at least two broad classes of mechanisms for why we might expect to see different answers to the questions above. The first class consists of legislators’ intrinsic motivations to respond differently to constituents of different ethnoraces. The second class consists of legislators’ strategic motivations, whereby legislators expect to gain an electoral or professional advantage by responding differently to constituents of different ethnoraces. Although we separate both mechanisms, they are likely both at work in many settings and interact in potentially counterintuitive ways (Giger, Lanz, and de Vries Reference Giger, Lanz and de Vries2020). We briefly unpack these two classes of mechanisms below.

Intrinsic Motivations

Elected officials may respond differently to constituents of different ethnoraces due to officials’ attachments to ethnoracial identities. A large body of literature interrogates the extent of such group attachments—both within and between ethnoracial groups—in the mass public. Far less research interrogates the role of group attachments among political elites. Nevertheless, such research on the mass public can inform our theoretical expectations about elites via a “supply side” account about which individuals from the mass public run for office (Canon Reference Canon1999; Dovi Reference Dovi2002). Swain (Reference Swain1993), Rouse (Reference Rouse2013), Tyson (Reference Tyson2016), Casarez Lemi (Reference Casarez Lemi2018), and Casellas (Reference Casellas2010), among others, connect the literature on the mass public to the elite behavior of white legislators. While much of this literature focuses on legislative voting, Mendez and Grose (Reference Mendez and Grose2018) find that bias against certain groups in the policy and non-policy (e.g., constituency service) realms are positively correlated.

Research suggests that stable racial attitudes are formed during adolescence, long before individuals could choose to run for office (see, e.g., Goldman and Hopkins Reference Goldman and Hopkins2020; Henry and Sears Reference Henry and Sears2002; Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996). Insofar as the public supplies elected officials with stable racial attitudes, then we might expect legislators’ senses of group identification to shape their responsiveness to constituents of different races, and indeed it is unsurprising that audit experiments among elites and the mass public yield similar results (Block Jr. et al. Reference Block, Crabtree, Holbein and Monson2021). This connection between the mass public and the elites they supply is especially pronounced given recent research from Hunt (Reference Hunt2022) and Hunt and Rouse (Reference Hunt and Rouse2023), which shows the importance of winning office of local roots and social embeddedness of legislators in their local constituencies.

Among racial minorities themselves, the existing literature largely agrees that Black Americans share a sense of “linked fate” (Dawson Reference Dawson1995). That is, Black individuals commonly believe that their well-being is tied to that of Black Americans as a group and use group status as a proxy for their individual utility when evaluating policies, parties, and candidates (see also McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009; Tate Reference Tate2003). The extent to which such group consciousness exists among other groups, for example, Latinos and whites, is an open question. Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2017) shows that a sense of linked fate often operates among white Americans, specifically those who perceive themselves as discriminated against, and makes it more likely for white Americans to desire white political candidates. For Latinos, Sanchez and Masuoka (Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010) assert that, even though Latinos lack a common history in the United States, some do perceive linked or common fate. This perception of linked fate, however, wanes as Latinos assimilate into mainstream American society. Spanish-speaking first-generation Latinos report the highest levels of linked fate, compared to later-generation bilingual or English-speaking Latinos.

Linking this literature on the mass public to political elites, Broockman (Reference Broockman2011) provides compelling evidence that Black legislators hold such a sense of group identification, which may make them more intrinsically motivated to respond to Black rather than white constituents. Harden (Reference Harden2013) also shows intrinsic motivations among both Black and white legislators, although these motivations are stronger for the former. Grose (Reference Grose2005), for example, argues that above and beyond the racial composition of districts, the presence of Black legislators impacts legislative behavior in the interests of Black Americans, thereby suggesting a mechanism of intrinsic motivation. For Latinos, Hero and Tolbert (Reference Hero and Tolbert1995) find little evidence of a relationship between the size of Latino constituencies and coethnic legislators’ voting patterns; however, Latino legislators do vote for legislation salient to their coethnic constituents, thus also suggesting a mechanism of intrinsic motivation.

Whether a sense of linked fate exists between Black Americans and Latinos is unclear. Survey research from the 1990s found that very few Latinos (around 14%) felt that they had things in common with Blacks (Masuoka Reference Masuoka2008). However, more recent research suggests that Latinos identify slightly more with African-Americans than with whites (Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa, Telles, Sawyer and Rivera-Salgado2011; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2014). Moreover, Fraga et al. (Reference Fraga, Garcia, Hero, Jones-Correa, Martinez-Ebers and Segura2011) find that a noticeable sense of linked fate exists between African-Americans and Latinos, perhaps because of shared experiences of discrimination (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003; White Reference White2007). Nevertheless, even if Blacks and Latinos are both disadvantaged minorities relative to whites, the two are not necessarily natural allies (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017), and experimental evidence has failed to find that shared social disadvantage causes greater political commonality between Black and Latino Americans (Israel-Trummel and Schachter Reference Israel-Trummel and Schachter2019).

Despite their focus on the mass public rather than elites, existing arguments about linked fate between different racial groups offer insight about the role a sense of linked fate plays in legislators’ responsiveness. Insofar as the mass public exhibits some degree of such linked fate, then the legislators supplied by this public will likely provide greater responsiveness to cominority constituents. Importantly, we would expect the group identification of legislators to shape how they respond to constituents of different ethnoracial groups regardless of legislators’ strategic motivations. For example, a legislator with a strong attachment to a racial minority identity—encompassing both Blacks and Latinos—may respond more to a Latino constituent than a white constituent even if there were few Latino voters and Black-Latino coalitions in that legislator’s district.

Strategic Motivations

In contrast to intrinsic motivations, an alternative mechanism posits that legislators are motivated chiefly by electoral incentives (Alt, Bueno de Mesquita, and Rose Reference Alt, Bueno de Mesquita and Rose2011; Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). In particular, legislators often have strategic incentives to respond differently to constituents of different ethnoraces. For example, Black legislators may believe that winning or maintaining the support of non-Black constituents is more difficult compared to Black constituents (Broockman Reference Broockman2011; Grose Reference Grose2011; Whitby Reference Whitby1997). Existing research suggests that the extent to which, for example, a Black legislator strategically benefits from responding more to both Black and Latino constituents relative to whites depends on the existence of “black-brown” coalitions. In short, legislators’ strategic incentives depend on the political landscapes—especially the racial composition of their districts—that legislators inhabit (Casellas and Leal Reference Casellas, Leal, Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2010, Reference Casellas and Leal2013). Insofar as voters of different races make up a common voting bloc, then legislators of a specific race have incentives to respond more to constituents of other races.

Coalitions between voters of different races may emerge under varied conditions. Common group attachments or policy agreements can create conditions ripe for the emergence of multiracial coalitions. For Blacks and Latinos in particular, Espino, Leal, and Meier (Reference Espino, Leal and Meier2008, 159) note that “Latinos do share considerable policy agreement with African Americans,” and Hero and Preuhs (Reference Hero and Preuhs2010) find that voting in the House of Representatives by Black and Latino legislators also reflects such policy agreements. Whether cross-racial coalitions do emerge depends on political incentives due to the relative sizes of racial groups (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; Casellas and Leal Reference Casellas, Leal, Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2010, Reference Casellas and Leal2013).

Along with other factors, Espino, Leal, and Meier (Reference Espino, Leal and Meier2008, 149) write that “the prospects for political coalition will be inexorably tied to the relative size of the two groups.” Benjamin (Reference Benjamin2017) makes a similar argument: it might make more sense for Blacks and Latinos to form coalitions with whites instead of with each other in cities where the Black or Latino populations are not as large. In these cases, competition between the two minority groups is more likely than cooperation. White legislators in districts with large minority populations may have incentives to appeal to cross-racial coalitions of voters. However, the literature on racial threat suggests that anti-Black and anti-Latino attitudes may increase among the white electorate, leading white legislators to decrease their support of minority interests.

Overall, the evidence for Black–brown voting coalitions is not particularly strong. For example, Benjamin (Reference Benjamin2017) notes that there is indeed evidence of high levels of coethnic voting in local elections. Blacks and Latinos electorally support candidates of their own ethnoracial groups. She also points out, though, that absent the option of supporting a coethnic candidate, the pattern of minority support is less consistent. Latino voters have, in some cases, supported a white candidate over a Black one, and Black voters have supported white candidates over Latinos.

In summation, legislators may have strategic motivations shaping to whom legislators respond. Insofar as Black and Latino coalitions are crucial to a minority legislator’s electoral success, then we would expect that legislator to respond more to a minority constituent of a different group relative to a white constituent. The existence of such coalitions will likely depend on the group identifications and policy agreements between ethnoraces, as well as the demographics of each group. Crucially, if only strategic (not intrinsic) motivations were at play, then we would expect minority legislators to respond to different minority groups only when they have electoral incentives to do so. A sense of broader group identification alone would not be enough.

Audit Experiments

To answer the questions at the heart of this paper, we conduct an audit experiment among state legislators in which we randomly vary the putative ethnorace of a constituent making a service request. Studies with similar designs have found conclusive evidence of racial bias in responsiveness at different levels of government, in terms of both the rate and the quality of responses. In addition to the work of Butler and Broockman (Reference Butler and Broockman2011) on white–Black relations, there is evidence of discrimination against undocumented Latinos (Mendez Reference Mendez2014), especially among Republican legislators (Janusz and Lajevardi Reference Janusz and Lajevardi2016). In a more recent study, Gell-Redman et al. (Reference Gell-Redman, Visalvanich, Crabtree and Fariss2018) found that Asian-Americans and Latinos who make constituency service requests to state legislators are discriminated against. While Republican legislators are the ones driving the negative effect toward Latinos, legislators in both parties equally discriminate against Asian-Americans.

There is also evidence of response bias at the municipal level. Butler and Crabtree (Reference Butler and Crabtree2017) show that white elected officials respond more to requests coming from white constituents than to requests coming from Black constituents, even after being provided with information on racial bias beforehand. Moreover, bureaucrats (e.g., public housing officials) are less responsive, and use a less friendly tone, when answering inquiries from Latinos, compared with white or Black individuals (Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017). White, Nathan, and Faller (Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015) reached a similar conclusion: Bureaucrats are less likely to reply (and emit lower-quality responses) to emails coming from Latino aliases in comparison with non-Latino, white aliases.

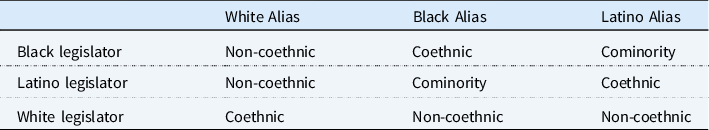

Like prior research, we estimate all state legislators’ differential responsiveness to putative white, Black, and Latino constituents, as well as whether such differential responsiveness varies among legislators who do and do not share the same ethnorace as the putative constituent. Previous work (e.g., Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011) shows that white elected officials are more likely to respond to white (coethnic) constituents than to Blacks, and that minority legislators (Blacks and Latinos taken together) are more likely to respond to Black constituents than to whites. Minority legislators, however, are broadly defined as a monolithic group, making it infeasible to determine whether they are also more responsive to coethnics or whether they exhibit cominority solidarity as well. How do Black and Latino legislators respond to coethnic and cominority cues? We follow Adida, Davenport, and McClendon (Reference Adida, Davenport and McClendon2016, 2) in defining a coethnic cue as “a cue appealing to the respondent’s ethnic or racial self-identification (for a Black respondent, this would be a Black cue; for a Latino respondent, this would be a Latino cue).” Similarly, a cominority cue is “a cue appealing to the respondent’s identification as part of an ethnic, but not a coethnic, minority group (for a Black respondent, this would be a Latino cue; for a Latino respondent, this would be a Black cue).”

While our interest is in responsiveness to coethnic and cominority cues, the treatment contrasts we consider are not whether the email sender is a coethnic vs. non-coethnic or cominority vs. non-cominority. Instead, we estimate average effects for three different treatment contrasts: white vs. Black, white vs. Latino, and Latino vs. Black. Doing so conveys more information in the initial point estimates compared to a coethnic vs. non-coethnic or cominority vs. non-cominority contrast. To see why, imagine that the estimated average effect of the coethnic vs. non-coethnic contrast among white legislators is positive. In this case, it would not be immediately clear whether that estimated effect is positive because of discrimination against Black non-coethnics or Latino non-coethnics. Likewise, for a cominority vs. non-cominority contrast, a positive estimated effect among, for example, Black legislators, would not immediately indicate whether the positive estimate is due to specifically coethnic or cominority solidarity. For these reasons, we focus primarily on binary combinations of the white, Black, and Latino treatments; however, the point and standard error estimates for the coethnic vs. non-coethnic and cominority vs. non-cominority contrasts can be backed out from the results we present.

Experimental Design

Sample

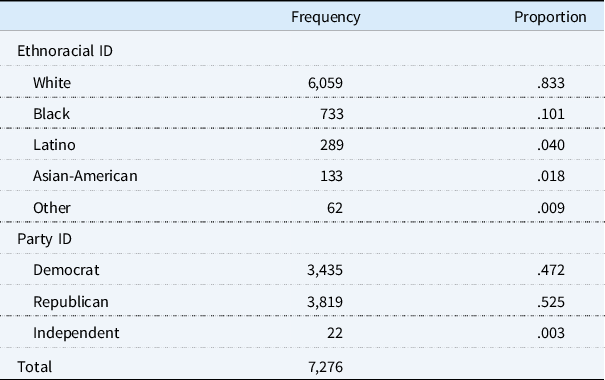

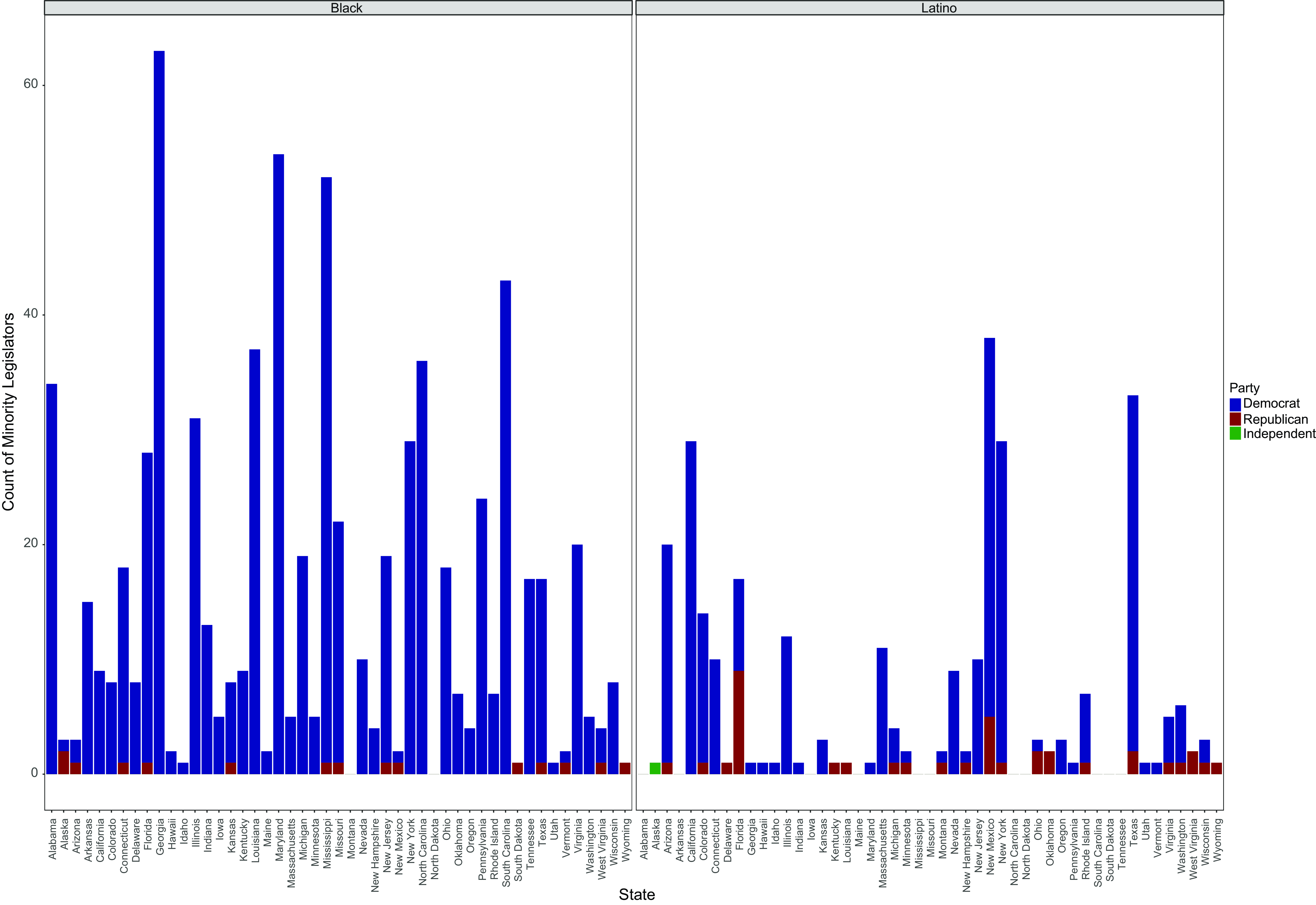

The sample consists of 7,276 state legislators in 49 states (excluding Nebraska’s unicameral and non-partisan legislature) and includes each legislator’s ethnoracial identity. Footnote 2 We initially identified the ethnoracial identity of these elected officials based on their names, biographical description, caucus membership, or phenotype as they appear on each state legislature’s roster on its respective website. We then cross-referenced our dataset with data from the National Association of Latino Elected Officials, the National Black Caucus of State Legislators, and the National Conference of State Legislatures. Finally, when still in doubt, we called the state legislative offices of those legislators for whom we could not find information and asked their staffers about the legislators’ ethnoracial self-identification. The result is a sample of more than 7,000 state legislators, 733 of whom are Black and 289 of whom are Latino. Every legislature has at least one minority member. Table 1 shows the ethnoracial and partisan composition of the legislators in the sample, and Fig.1 shows the number of Black and Latino legislators by party and state. (Table D2 in Appendix D shows the share.)

Table 1. Ethnoracial and partisan composition of state legislatures

Figure 1. Black and Latino legislators by party and state

The sample includes only legislators with valid email addresses that were available online through state legislative websites or personal websites in January 2020. To check for email validity before sending the emails, which otherwise could bias the estimates, we use an online service of email verification (BriteVerify). We ran the list of email addresses through their system and found replacements for those addresses that failed the verification test. Once those particular email addresses were replaced, we verified the new list. Finally, we eliminated from the list those emails that failed the initial verification test and for which we were unable to find a replacement. This process, plus the powerful spam filters that some legislative email servers employ to automatically reject emails from unknown domains, inevitably reduced the sample size. In the end, 5,911 emails (or 81.23% of the original sample and 80.1% of the population) were successfully sent and delivered to state legislators.

It is important to note that, like Butler and Broockman (Reference Butler and Broockman2011), this experiment treats state legislators’ email addresses and not necessarily the state legislators themselves. Staff members may be the ones responding, or failing to respond, to constituents’ requests. Nevertheless, staff members respond in an official capacity on behalf of the legislators, and, as research suggests, staffers reflect the race and other characteristics of legislators (Baekgaard and George Reference Baekgaard and George2018; Grose, Mangum, and Martin Reference Grose, Mangum and Martin2007; Jones Reference Jones2022, Reference Jones2017).

Random Assignment of Treatment and Identification Strategy

In the experiment, each legislator is randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: information requests from a white, a Black, or a Latino constituent. For example, each Black legislator receives an email from a coethnic (Black), a non-coethnic (white), or a cominority (Latino) constituent presenting an inquiry that requires an answer.

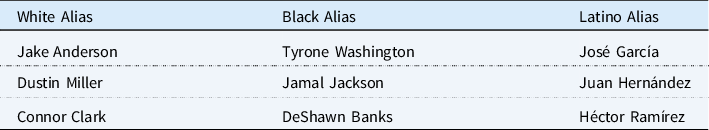

In order to make the noninterference assumption more plausible, we randomly assign the text of the email as well. Footnote 3 Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Gell-Redman, Crabtree, Krishnaswami, Rodenberger and Monge2020) follow the same strategy for the same specific purpose. There are three possible email types and three different wording styles within each. Moreover, following Bertrand and Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004), we use a portfolio of three names for each of the ethnoracial groups rather than just one name per group. The name that accompanies each email message is randomized within ethnoracial group. There are thus 81 possible combinations of the 9 ethnoracially distinctive names, 3 email types, and 3 wording styles. This approach ensures that any observed treatment effect does not pertain to any particular name or type of email. After estimating these average treatment effects (ATEs) in the full sample, we estimate the conditional average treatment effects (CATEs) of the ethnoracially distinctive names in subsets of the data, namely, white, Black, and Latino legislators on the one hand and Republican and Democratic legislators on the other.

When we estimate the CATEs by race, we use the legislator’s ethnoracial identity as the basis for the analysis and classify the treatments in relation to whether they match the ethnorace or minority status of the constituent (see Table 2). We follow Adida, Davenport, and McClendon (Reference Adida, Davenport and McClendon2016, 2) in defining a coethnic cue as “a cue appealing to the respondent’s ethnic or racial self-identification (for a Black respondent, this would be a Black cue; for a Latino respondent, this would be a Latino cue).” Similarly, a cominority cue is “a cue appealing to the respondent’s identification as part of an ethnic, but not a coethnic, minority group (for a Black respondent, this would be a Latino cue; for a Latino respondent, this would be a Black cue).” Finally, a non-coethnic cue correponds to an outgroup member who is neither a coethnic nor cominority (for a Black respondent, this would be a white cue; for a white respondent, this would be a Black or a Latino cue).

Table 2. Treatment conditions

Intervention

The treatment—the ethnoracial identity of the constituent—is implied by the email alias and is explicit in the text of the email message. The racial “soundingness” of a name, even if subtle, is a cue that conveys information pertaining to an individual’s identity and can elicit different responses from those in positions of power (Bertrand and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004; Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011). To decide which names to use, we first selected five surnames from the “Frequently Occurring Surnames in the 2010 Census” report (Comenetz Reference Comenetz2016) and five names from comparable lists of common Latino, white, and Black names in the United States. To verify that these names may indeed serve as ethnoracial cues, we follow the practice proposed by Gaddis (Reference Gaddis2017) in conducting a pretest (N = 100) on MTurk in which we asked respondents to classify each of the names on the list by ethnoracial group. Footnote 4 The results, presented in Table B1 in Appendix B, show that an overwhelming majority of respondents classified the names into the “correct” ethnoracial category, except for the alias Trevon Booker. For this reason, we excluded this alias from our experiment and selected the three aliases with the highest percentage of “right” answers in each ethnoracial group (Table 3). After being randomly assigned to one of three ethnoracial treatment conditions, legislators are then randomly assigned to receive an email from one of the three names within the assigned ethnoracial group. Footnote 5

Table 3. Putative White, Black, and Latino names and surnames

In addition to the name of the email sender, we also include an explicit reference to Black or Latino group membership in the body of the email to strengthen the treatment and, consequently, send a more explicit ethnoracial cue. The constituent’s partisanship always matches the legislator’s, such that, under certain assumptions, any observed differences in legislators’ responsiveness cannot be attributed to strategic partisan considerations. Moreover, all the email aliases correspond to male senders in order to rule out possible gender effects. Nevertheless, legislators may infer other, latent attributes that are not directly cued by our treatment. We argue that such inferences about, for example, the class or religiosity, of constituents are a feature rather than a bug of ethnoracial discrimination, reflecting the ways in which to be racialized “is to be socially positioned in the way indicated by a certain set of statistical regularities on the basis of particular phenotypic traits” (Hu Reference Hu2023, 1).

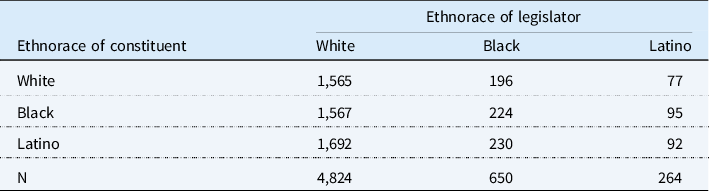

Table 4 shows the number of subjects assigned to each treatment condition. Footnote 6 Looking within legislators’ ethnoracial groups (along the columns), roughly a third of the subjects were randomly assigned to each of the white, Black, and Latino constituent treatments. Noteworthy in this table is the small number of Latino legislators in the sample (N = 264); consequently, the number of Latino legislators assigned to each treatment condition is under 100. The number of Black legislators is also considerably smaller than the number of white legislators, but larger than the share of Latinos.

Table 4. Distribution of assignments

Figures 2–4 in Appendix C provide the full text of the emails sent to white, Black, and Latino state legislators. Italicized items were assigned randomly based on the treatment condition, while items in brackets were manipulated across emails to match the recipient’s characteristics. Each legislator received one email from a Black, Latino, or white hypothetical constituent. The text of the email consisted of a request for constituency service, which could be of one of three types: an inquiry about internship opportunities, a request for information on how to get more involved in politics, and a question about campaign work.

Among the different types of representation (see Harden Reference Harden2013), previous research suggests that legislators may be more likely to respond to constituency service requests because they “cultivate an image or reputation for helpfulness, sympathy, courtesy, and hard work” (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012a, 476). Policy-oriented messages, on the other hand, are less likely to elicit responses because elected officials may be wary of offending the constituents (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012a). Costa (Reference Costa2017), however, finds that there is no statistically significant difference between service and policy communications in audit studies of elected officials. More importantly for our purposes, though, a request for information regarding internship opportunities, political involvement, or campaign work allows us to examine legislators’ responses to issues on which animosity between minority groups does not exist. In addition, this type of question should not influence the policymaking process or policy outcomes in any way.

The outcome of interest is the legislator’s responsiveness—i.e., a binary measure of whether he or she responds (1) to the inquiry or not (0). The dataset also includes information on a battery of covariates, the most important of which for the forthcoming analysis are legislators’ race, party, and district racial composition. Footnote 7 These data allow us to estimate subgroup and heterogeneous treatment effects by the ethnoracial and partisan identities of the legislators, as well as by their districts’ racial compositions. The emails were sent in January 2020, and the responses were collected up to a month after receipt of the message. Costa (Reference Costa2017) finds that waiting longer for responses does not necessarily yield a higher number of responses.

Descriptive Statistics

We descriptively assess the response rates by legislators’ ethnoracial and partisan identities. Table 5 presents the results. This table includes Asian-American legislators and legislators of “other” ethnoracial identities. These are legislators who identify as Native American or Native Hawaiian, for example, and of whom there were few (52) in total. Asian-Americans and those grouped under “other” ethnoracial categories are not included in most analyses because the theoretical expectations laid out in “Theory and Existing Evidence” only speak to Black–Latino relations and the treatment conditions were designed correspondingly. However, we take note of these two sets of identities and include them in this section for descriptive purposes; their numbers are too small to draw meaningful inferences from.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics: response rate by email type and legislators’ partisan and ethnoracial identities

Table 5 reveals interesting patterns of responsiveness. Asian-American and white legislators are the most likely to respond to emails from their constituents. These two groups are followed by those who fall under the “other” category, by Latinos, and finally by Black legislators. Some of the differences are considerable—for example, 37.2% of Asian-American legislators replied to emails while 27.4% of Black legislators did the same—but these response rates pertain to all constituents taken together, without making any ethnoracial distinctions. We next assess the response rates to all constituents by legislators’ partisan identification. The results suggest that Republican and Democratic legislators reply to emails at roughly the same rate (36.7% vs. 36.4%, respectively). There are only 20 Independents in the sample, and they respond at a lower rate (30.0%). Partisan differences in overall response rates are very small. Finally, Table 5 shows the response rates by email type. The political advice and campaign email types are substantively similar, so it is no surprise that they receive a similar proportion of replies (35.5% and 33.5%, respectively). There is a difference between these two and the internship email type. (This difference is statistically significant at the α = .01 level.) The internship email is the most likely to receive responses (40.5%). This result is to be expected given that prior research suggests that questions about specific services—for example, an internship request—receive more responses as opposed to those about political or policy advice (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012b).

Results

As we wrote in the introduction, this paper aims to answer two related questions: Are white legislators equally responsive to all minority constituents? And are minority legislators as responsive to cominority constituents as they are to white constituents? Answers to both of these questions are important. The vast majority of state legislators are white, and these legislators may discriminate against non-white constituents. However, if minority legislators also discriminate against minority constituents, then increasing the number of minority legislators would not necessarily lead to greater overall responsiveness to minorities. In short, responsiveness among both white and non-white legislators matters, as does the difference in responsiveness between these two groups of legislators.

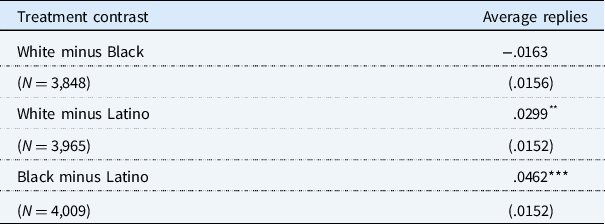

We begin by presenting average differences in responsiveness among all legislators. Table 6 shows strong evidence of discrimination among all legislators, on average, against Latinos in favor of either white or Black constituents.

Table 6. Estimates of average effects among all legislators with working email addresses

Note: *p < .1.

**p < .05.

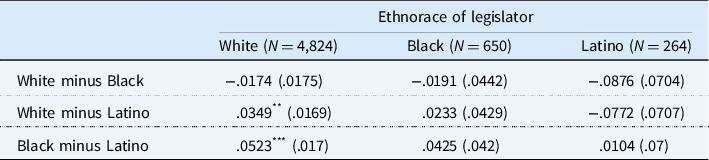

Given that the vast majority of legislators are white, the results in Table 6 are driven primarily by differential responsiveness among specifically white legislators. To shed light on the importance of descriptive representation, we now analyze subgroup effects. The first analysis assesses whether there are benefits of coethnic representation for Black relative to white constituents and then for Latino relative to white constituents. The second analysis assesses whether there are benefits of cominority representation, first for Black relative to white constituents and then for Latino relative to white constituents. Table 7 presents the same estimates separately among white, Black, and Latino legislators. Standard errors are estimated via the conservative procedure proposed by Miratrix, Sekhon, and Yu (Reference Miratrix, Sekhon and Yu2013).

Table 7. Difference-in-means by legislators’ ethnoracial identities

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < .1.

**p < .05.

***p < .01.

Coethnic Descriptive Representation

Table 7 shows little evidence of coethnic benefits to descriptive representation of Black constituents. That is, the evidence does not establish that Black legislators respond more to Black constituents than white constituents. Moreover, these results illustrate that the lack of coethnic benefits of descriptive representation for Black constituents is a function of—contrary to existing findings—white legislators’ lack of discrimination against Black constituents in favor of whites. One reason for this result may be that, as Iyengar and Hahn (Reference Iyengar and Hahn2007, 3) note, “racial bias is more likely to emerge when the racial content of the triggering stimulus is latent (implicit) rather than manifest (explicit).” Hence, our experiment’s explicit racial cue in the body of the email may produce less discrimination, which is a question that is in need of further inquiry (along the lines of, e.g., Kirgios et al. Reference Kirgios, Rai, Chang and Milkman2022).

However, Table 7 does suggest that there may be coethnic benefits of descriptive representation for Latino constituents. From Table 7, one can infer that the estimated interaction effect of the Latino vs. non-Latino treatment among Latino and white legislators narrowly misses the statistical significance threshold due to the inevitably greater variance of interaction effect estimators. However, the estimated effect among white legislators is negative and significant (−.0426), thereby suggesting anti-Latino discrimination among white legislators. Among Latino legislators, the point estimate is positive suggesting the benefits of coethnic descriptive representation, although, with such few Latino legislators, this estimate is not significant. Thus, the evidence suggests that the coethnic benefits of descriptive representation for Latino constituents could be due to Latino legislators’ greater responsiveness to Latino relative to white constituents; however, this estimate (Row 2 and Column 3 of Table 7) is not significant, even though its magnitude is high. Instead, the evidence more definitively suggests that the key driver of descriptive representation’s benefits for Latinos is white legislators’ discrimination against Latino constituents in favor of both white and Black constituents.

Cominority Descriptive Representation

Table 7 shows no evidence of cominority benefits for Latinos. There is strong, statistically significant evidence that white legislators discriminate against Latino constituents in favor of whites. The direction of the point estimate among Black legislators also suggests discrimination against Latino constituents in favor of whites, but this result is not statistically significant. Hence, there is no evidence that, despite anti-Latino discrimination among white legislators, Latinos would achieve better responsiveness relative to whites by Black legislators.

In terms of cominority benefits for Black constituents, there is no evidence of discrimination against Black relative to white constituents among white legislators. Among Latino legislators, the point estimate suggests that there may be the benefits of cominority representation for Black constituents in terms of Latino legislators’ responding more to Black relative to white constituents. However, given the paucity of Latino legislators, this result lacks statistical significance. Thus, in terms of cominority benefits of descriptive representation, any cominority benefits of descriptive representation are likely to be driven by (a) Latino legislators’ greater responsiveness to Black relative to white constituents and (b) white legislators’ lesser responsiveness to Latino constituents.

Secondary Analysis Suggestive of Causal Mechanisms

From this audit experiment, a clear pattern emerges of white legislators’ discrimination against Latinos in favor of Black or white constituents. There is also some evidence of Latino legislators’ providing greater responsiveness to both Black and Latino constituents relative to whites. Black legislators do not appear to discriminate in their responses to either white, Black, or Latino constituents. Thus, this experiment provides strong evidence that, insofar as increasing the number of Black or Latino legislators will increase descriptive representation for Latinos, it is due to the high levels, on average, of anti-Latino discrimination among white legislators.

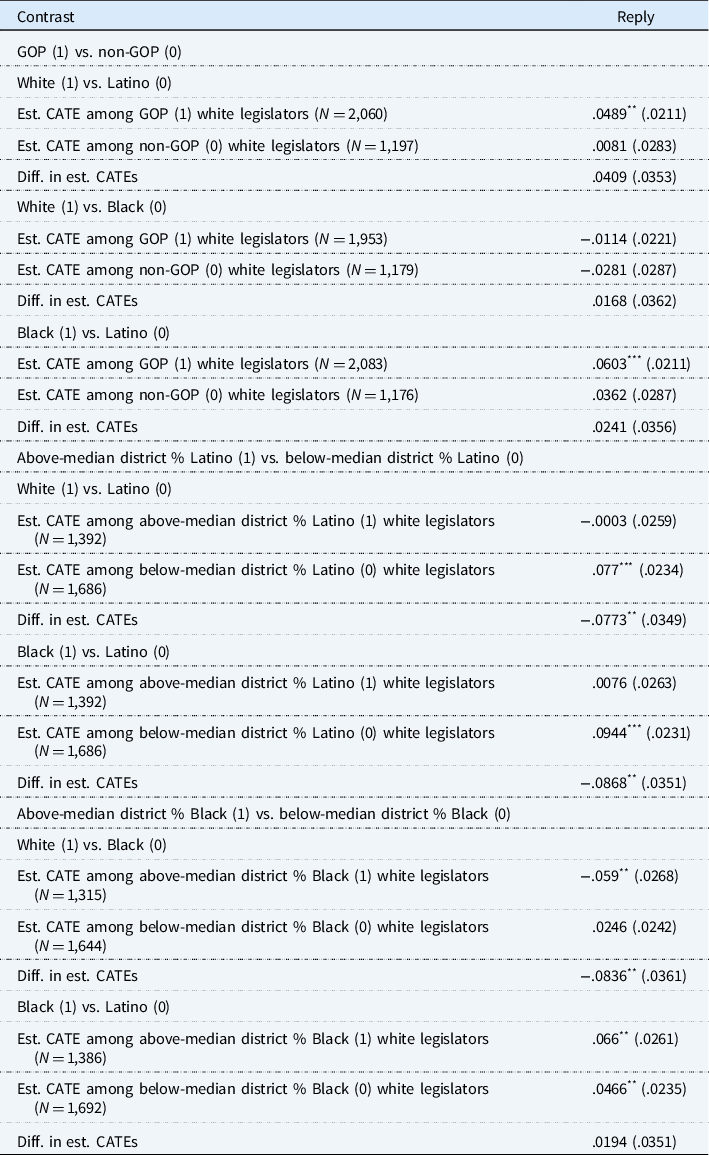

A remaining question is why we see anti-Latino, but not anti-Black, discrimination among white legislators. We now provide suggestive evidence for the two mechanisms outlined in our theory above. Table 8 provides additional evidence that points to plausible mechanisms for white legislators’ discrimination against Latino constituents and lack thereof against Black constituents.

Table 8. Heterogeneous effects by party and district % Latino among white legislators

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < .1.

**p < .05.

***p < .01.

Table 8 shows, first, that anti-Latino discrimination among white legislators exists among Republicans. We are unable to detect such discrimination among non-Republicans, although the difference in the two subgroup estimates is not statistically significant. Dinesen, Dahl, and Schiøoler (Reference Dinesen, Dahl and Schiøoler2021) provide evidence that party affiliation is a useful heuristic for ethnoracial bias, and Costa and Schaffner (Reference Costa and Schaffner2018) make a similar claim about the ways in which gender stereotypes operate differently for Democrats than Republicans. In our experiment, insofar as Republicans tend to harbor negative attitudes toward Latinos relative to Democrats, then the significant effect among Republicans (but not Democrats) suggests that an intrinsic, attitudinal (rather than strategic, electoral) motivation may be at play among white legislators. Overall, it is surprising that Republicans are more responsive to requests by Blacks than Latinos, given that Latinos are far more likely than Black voters to support Republican candidates. Footnote 8 Hence, the differential responsiveness to Black relative to Latino constituents suggests an intrinsic, attitudinal motivation among Republicans.

Among white legislators of both parties, the average level of discrimination against Latinos relative to white or Black constituents varies depending on the proportion of Latinos in legislators’ districts. That is, for white legislators in districts with a proportion of Latinos above the median, there is little evidence of discrimination against Latinos in favor of white or Black constituents. Anti-Latino discrimination in favor of white or Black constituents appears to be concentrated among white legislators in districts with few Latinos (specifically a district proportion of Latinos below the median). The difference between these two subgroup effects (i.e., the interaction effect) is also statistically significant.

A similar pattern holds for discrimination against Black relative to white constituents. White legislators respond more to Black relative to white constituents in districts with a greater Black population (a district proportion of Black constituents above the median). In districts with fewer Black constituents (a district proportion of Black constituents below the median), white legislators appear to respond to white and Black constituents at roughly equal rates. The difference between these two subgroup effects is also statistically significant.

These findings may suggest a strategic mechanism in which white legislators have incentives to appeal to multiracial coalitions in more racially diverse districts. However, such a conclusion may not be warranted. It could also be the case that white legislators who come from more racially diverse social contexts may harbor less anti-Black or anti-Latino sentiments (see Sobolewska, McKee, and Campbell Reference Sobolewska, McKee and Campbell2018). Further research is needed to parse these separate possibilities. Nevertheless, the fact that we observe less discrimination in more racially diverse districts provides suggestive evidence against the mechanism of racial threat (as described by, e.g., Enos Reference Enos2014, Reference Enos2016), whereby increasing minority populations results in more exclusionary attitudes by the white population. White legislators (who have often come into office because of their social embeddedness in their respective districts) do not appear to harbor more exclusionary attitudes due to greater exposure to racial minorities.

Conclusion

The goal of this experiment, conducted in January 2020, was to test whether legislators’ responsiveness to constituents’ information requests depended on the constituents’ ethnoracial identities. We were specifically interested in taking legislators’ own ethnoracial identities into account when asking and attempting to answer this question. We also considered heterogeneous effects by legislators’ partisanship.

Our analyses show no evidence to support the claim that legislators (of all ethnoracial identities) are more responsive to white constituents than to Black constituents. We do find, however, strong support for the claim that legislators are more responsive to white constituents than to Latino constituents, as well as strong evidence that legislators respond more to Black constituents than to Latinos. Focusing exclusively on white legislators, the results are very similar to those of the full sample. White legislators are considerably more responsive to white constituents when compared to Latinos and to Black constituents when compared to Latinos.

Turning next to minority legislators, we find no evidence to suggest that Black legislators respond differently to constituents of different ethnoracial backgrounds. In other words, Black legislators do not exhibit coethnicity in responsiveness to Black constituents or cominority solidarity toward their Latino constituents. For Latino legislators, point estimates suggest coethnic solidarity toward Latino relative to white constituents and cominority solidarity toward their Black relative to white constituents, but there are too few Latino legislators to definitely establish these claims.

This experiment establishes that the benefits of coethnic or cominority descriptive representation will be driven in large part by white legislators’ discrimination (or lack thereof) against both Latino and Black constituents relative to whites. The greater responsiveness among white Republican legislators to Black and white constituents relative to Latinos suggests that an intrinsic, attitudinal motivation is at play. On the other hand, the statistically significant differences in white legislators’ responsiveness to Black constituents relative to whites and Latino constituents relative to whites suggest that perhaps a strategic, electoral mechanism is also at play. We note, however, that it is difficult to parse the possibility that white legislators from racially diverse districts have different intrinsic motivations from legislators in less diverse districts, or whether legislators in the former districts have greater strategic electoral incentives to respond to racial minorities.

Finally, this study raises a host of unanswered questions that may be the subject of future research. For one, there are interesting differences in legislators’ reply rates (as shown in Table 5) that our current design cannot explain. Why are some types of legislators generally more responsive than others? Relatedly, what is the role of gender in legislative responsiveness? Thomsen and Sanders (Reference Thomsen and Sanders2020), for instance, show that women legislators are more responsive to their constituents compared with male legislators. How do race and gender interact to shape legislator–constituent interactions? Lastly, while we assess causal mechanisms about the role of race in legislative responsiveness among specifically white legislators, future work would benefit from parsing mechanisms among non-white legislators.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.30

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Paloma Castillo and Kate Bowman for their invaluable work during the data-gathering process; Robert Y. Shapiro for his mentorship and guidance; and Thomas Leavitt for his invaluable feedback on the multiple iterations of this paper. Participants of the American Political Science Association, Midwest Political Science Association, and Symposium on the Politics of Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity (SPIRE)—as well as Viviana’s colleagues (Neil Hernandez, Shreya Subramani, and Emily Pelletier) and mentor (Lina Newton) at CUNY’s Faculty Fellowship Publication Program—also offered helpful observations on earlier versions of this manuscript. This project was made possible in large part thanks to funding from the Consortium for Faculty Diversity at Wellesley College and the Political Science Department’s Dissertation Development Grant at Columbia University.