Books have always shaped the culture of politics, religion, education, leisure, trade, and knowledge but, as The Bookshop of the World by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen has shown,Footnote 1 their role in influencing opinion during early modern times was even a more important than it is today. Robert Darnton, in his model of the circulation of books (so-called communication circuit), has highlighted how books cannot merely be considered the product of authorial conception. Culture is dynamic, and books represent the cultural and material constructs of not only the author, but of the publisher, printer, bookseller, and reader as well.Footnote 2

Darnton's insight corresponds with other cultural historical notions, such as cultural transfer and cultural translation, which demonstrate that the transfer of media objects and practices from one culture to another never simply implies reproducing or copying. There are almost always both appropriation and productive reception, which take place as the media are transferred from one culture to another (cultural transfer).Footnote 3 Moreover, when translating texts, both decontextualization and recontextualization take place (cultural translation). Decontextualization occurs through the appropriation by a new culture, and this often includes an elimination of characteristic elements from the source culture. Recontextualization, on the other hand, occurs by way of connection with typical elements of the new culture.Footnote 4 In the time period being studied, this genre of devotional books offered fertile ground for the phenomena associated with both cultural transfer and cultural translation.

The primary aim of a devotional book was to instruct rather than inform readers about living in accordance with doctrine.Footnote 5 In early modern Europe, according Franz Eybl,Footnote 6 these works made up one-quarter of the total of all book production. My proposal is that, although some work has been done on both the circumstances under which, and the manner in which, devotional books were translated in early modern Europe, there is room for the development of a more systematic theoretical framework of research. This article proposes a suitable framework in the form of a case study to test several unanswered questions.

The processes that gave rise to decontextualization and recontextualization can be said to have occurred at the crossroads between printing, translation, and dissemination—when religious books were printed many times, translated into many languages, and traveled across borders governing religious communities. This was true not only from one confession to another, but also from one community to another within the same confession. The following examples help illustrate this.

First, adaptation of a text seems to have been necessary when large confessional differences between the source culture and target culture existed, for example, when a Catholic text was adjusted for a Protestant audience. Maximilian von Habsburg maps out a set of rather static strategies for the “Protestantization” of Thomas a Kempis's Imitation of Christ (1418–1427).Footnote 7 Ine Kiekens, in a case study on a Protestant adaptation of a Late Medieval Dutch treatise on virtues, demonstrates that the measure of decontextualizing and recontextualizing depended on the time period when the adaptation was made in relation to the intended audience for which it was made. For example, during a time of transition to the Reformation, many but not all Catholic elements were left out of a Lutheran adaptation of 1565. The cult of saints, for example, remained.Footnote 8

Second, differences also existed within Protestantism, between the Lutheran and Reformed confession, especially in the relationship of justification and sanctification—as well as predestination and the sacraments.Footnote 9 These discrepancies led German Lutheran translators of English Reformed devotional writings during the seventeenth century to adjust certain passages of the source text to Lutheran doctrine. Nevertheless, Udo Sträter is of the opinion that, since the 1670s, translators had increasingly given up doctrinally adapting the text—and instead made only minimal linguistic changes when transferring the content from the Reformed opinions on predestination and atonement, into the Lutheran framework of regeneration, repentance, and faith.Footnote 10

The third example is that, even within one confession, opinions on ecclesiastical governance structure, as well as on certain doctrines, could differ. Hence the reason translators altered specific passages of texts—as was the case in Dutch translations of The Practice of Piety (before 1612) of the theologian Lewis BaylyFootnote 11 (c.1575–1631).Footnote 12 As this devotional book was written by a clergyman of the Church of England and translated for different Protestant communities—both Reformed and Lutheran on the European continent—the writing offers an excellent case study into processes of cultural translation in early modern Europe.

In light, then, of the three examples above, this article builds on scattered data currently available that speak to the international circulation and reception of Bayly's book.Footnote 13 It briefly outlines the international dissemination and popularity of the book and discusses the question of the circumstances under which its textual contents were criticized or welcomed, appropriated, decontextualized, and recontextualized; as well as how, by whom, through which channels, and for which audiences.Footnote 14 My contribution in developing a theoretical framework engaged in the study of cultural translation is structured in three sections as follows:

The first section consists of a short overview of Bayly's biography and of his Practice of Piety, specifically its ranking on the list of European devotional bestsellers. The second section looks in depth at the production, circulation, and reception of Bayly's book in several language areas, specifically seeking answers to the following. First, why, how, and by whom did the text, or an adaptation of it, come into being; and was it recorded in a manuscript or printed (production)? Second, why, how, and by whom was the text disseminated or sold (circulation)? Last, why, how, and by whom was it bought, used, read, changed, referred to, and what impact did it have on people?

My proposal is that answers to these questions can be found in references to Bayly's Practice of Piety in printed and archival sources such as library inventories, in auction catalogues, and in resources such as (retrospective) bibliographical works. It would be unfeasible to undertake systematic research of all the possible relevant sources because of the high number and widespread nature of these sources. My efforts to outline the international production, circulation, and reception are therefore concentrated almost entirely on scholarly literature. The occasional primary sources are limited by those modern foreign languages in which I am proficient. For the Dutch translation, I have been able to rely on my earlier in-depth comparison of the source text with its translation.

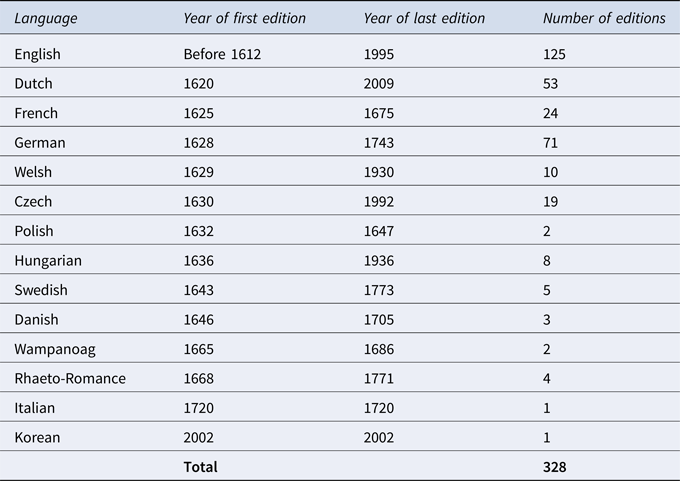

The aim of this second section is to compare the production, circulation, and reception of Bayly's book in the area of the original language (English) with that of other areas where a translation of the book had been published, and to analyze these communication circuits. To that end, I have made a representative selection of language areas from those in which the book was published, using printed and digital bibliographic tools (see Table 1).Footnote 15

Table 1. First edition and number of editions of Bayly's book in each language

This selection of language areas to be studied reflects differences in the number of editions in which Bayly's writing appeared; their geographical spheres of influence (America, Central Europe, Northern Europe, or Western Europe); the political and social status of a language (majority/minority); and the confessional communities that were present at that moment in a given area.

In addition to the language area of the source text (the English-speaking world), this selection includes areas that, first, differ regarding the confessional communities in which Bayly's book was translated, printed, and read; and, second, for which the production, distribution, and reception of Bayly's text has been sufficiently studied. Accordingly, the Dutch and German language areas were selected because the Dutch Reformed Church was more Calvinistic than the Church of England, and because, in the German language, Bayly's book was quite popular among Lutherans.Footnote 16 Taken together then, these language areas allow us to compare a variety of religious constellations, and these groupings help us to analyze their effect on the production, circulation, and reception of Bayly's work.

The third section of this article uncovers a suitable theoretical framework; discusses the circumstances under which Bayly's book and its contents were appropriated, decontextualized, and recontextualized; and also how, by whom, through which channels, and for which audiences.

Lewis Bayly and His Practice of Piety

It is helpful to begin by placing the author in context. Lewis Bayly was probably born in Carmarthen, Wales. After his studies at Oxford, he received several church preferments in England, and it was around 1603 when he was appointed to serve as chaplain to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales. In 1611 he became treasurer of St Paul's Cathedral. He received his Bachelor of Divinity at Oxford, and in 1613 he received his Doctor of Divinity. A year later he was appointed as one of the chaplains of King James I and in 1616 to the bishopric of Bangor (Wales). Bayly's relationship with King James and with his successor Charles I must have been a difficult one because Bayly was imprisoned by the king in 1621–1622 as a result of a disagreement over Sabbatarianism.Footnote 17 And in 1630 Bayly was required by King Charles to account for his performance as a bishop, after he was accused of appointing Nonconforming Puritans and incompetent clergy, as well as for insufficient supervision of his diocese.Footnote 18

Bayly's main written work—The Practice of Piety—was most likely published in 1611Footnote 19 and thus written during his period as chaplain to the Prince of Wales. During this time and since the pre-Reformation period, the demand for “godly living handbooks” had been growing. In these books, parents and householders were instructed on how to lead regular domestic worship and how to teach their children and servants to live well. Examples of such works are Werke for Householders (1530) by the monk Richard Whitford and A Godly Form of Householde Government (1598) by the Protestant minister Robert Cleaver. These and other books were however no competition for Bayly's work as it expanded through many editions. Its popularity may in part be explained by the fact that these consecutive enlargements turned it into a most comprehensive work—while also able to be published in smaller, more manageable, and cheaper formats.Footnote 20 This made Bayly's book, in the words of Alec Ryrie, “the uncontested champion of early modern British Protestant writing.”Footnote 21

The structure of the book itself is interesting too. Bayly starts his book with a short exposition on God, his essence, persons, and attributes. He then moves on to deal with meditations on the two conditions in which mankind can live. In the first condition, dealing with the misery of unconverted people, the mood is very dreary. By contrast, the second condition, dealing with the blessedness of the converted, is glorious. Bayly then describes some obstacles to practicing piety such as misinterpreting the Bible and the Christian religion, how prominent people can set a bad example, and misuse of God's forbearance. It thus moves from an acknowledgment of the Creator and Savior to the sinful condition of man, and then on to the glorious gift within reach, ending with words of caution. In this sense then, by transitioning between acknowledgment, repentance, and glory, it presents itself to the reader in an uplifting, positive manner.

After these introductory sections, the main part of the book is concerned with practical advice about what is required of man. This then introduces the practice of piety in both an ordinary and extraordinary manner. For the ordinary daily piety, Bayly prescribes a repeatable pattern consisting of prayer, Bible reading, and Psalm singing to be applied at various times in the day—both individually and with the household, by the man in his role as head of the house. When praying, one should confess one's sins, pray for their forgiveness, pray for the improvement of one's life, give thanks for received mercies, and do intercession—not only for family members but also for the whole church of God and for political authorities.

Bayly devotes considerable attention to practicing piety on the Sabbath, which he argues extensively as having been commanded by God, not only for the nation of Israel in the old dispensation but for everyone and always. According to Bayly, the Sabbath consists of strictly refraining from daily occupations and meditating on God and salvation, both before, during, and after worship service. It is characteristic of Bayly that he also prescribes meditating on God's creation by going outside into the fields to reflect on God's might, wisdom, and goodness, and urging readers to think of the poor and sick on the Sabbath.

Moreover, Bayly addresses the extraordinary practice of piety both personally and publicly during fasting, as well as during feasting. The first exercise is marked by abstaining from daily occupations, food, and the like; the second is focused on the celebration of the Lord's Supper and is similar to the Sabbath, in that one should meditate before, during, and after the sacramental service.

Finally, the practice of piety during sickness, dying, and martyrdom is addressed. Strikingly, in the section on sickness, it is sin and confession of sin that are the central ideas, while in the parts on dying, consolation against the temptations of the devil, against suffering, and fear for death are more pivotal. Bayly's books ends with a dialogue between the believing soul and the Savior, and a soliloquy on the passion of Christ.

Bayly's writing became a bestseller demonstrated by Hartmut Lehmann in 1980, who calculated the total number of editions of devotional bestsellers in Europe from 1600 to 1740. Thomas a Kempis's Imitation of Christ was published in about 550 editions; Johann Arndt's (1555–1621) Four Books on True Christianity (1605–1610) was published in 123 editions; the main works of François de Sales (1567–1622) in 100 editions. Bayly's book, by contrast, totaled ninety-four editions.Footnote 22 Referring to Table 1, it can be seen that Bayly's currently estimated total number of editions of 328 is much higher than Lehmann's calculation. However, it is best to use Lehmann's figures here, as the table's figures would require accurately account for the additional translations of these other books.

In applying Lehmann's data, it is worth pointing out two additional factors that complicate the ranking of Bayly's book in the list of most popular devotional books in early-modern times. First, Lehmann did not take into account the high number of editions of Sacred Meditations to Excite True Piety by Johann Gerhard (1582–1637), which was printed 115 times in the period from 1607 to 1700.Footnote 23 Accordingly, Gerhard's book should be placed between Arndt and de Sales in the ranking. Second, the figure describing the De Sales's book does not refer to one but to a combination of three books. It can thus hardly be assumed that any one of these writings was printed more than ninety-four times. In summary, it is very complicated to delineate the ranking of Bayly's work on the basis of present data, but the book does appear to comfortably sit at number four on the list of most popular devotional books of early-modern Europe.

It is also worth noting that much later, at an international level, Bunyan's famous Pilgrim's Progress (published for the first time in 1678) overshadowed all previous devotional books. By 1740 this work had registered sixty-one editions internationally and by 1938 at least 1,300 editions had appeared (and many more since); it was translated into over 200 languages.Footnote 24

Bayly's Book in Individual Language Areas

English

Although, or maybe even because, Bayly was a controversial person, editions of his book appeared frequently during his lifetime. It was a trend that continued until the end of the eighteenth century,Footnote 25 but there were several other considerations that account for the popularity of the book in the English language. First, the book played a major role in people's lives, as evidenced through admiration expressed by the readers themselves. Some were instructed by it into the Christian faith or, like the later Latitudinarian bishop Simon Patrick (1627–1707),Footnote 26 read it in their youth. For others. The Practice of Piety was an instrument to their conversion, such as for Elizabeth Wilkinson née Gifford (1612/1613–1654). As a child of twelve, she read in Bayly's book about the hellish terror of the godless and the heavenly pleasure of the godly, which made her so afraid that she began to live an exemplary life. For the later Baptist preacher John Bunyan (1628–1688), too, Bayly's writing was instrumental for his outward conversion. His wife had brought the book with her into marriage as one of her few properties.Footnote 27 Moreover, dying people were consoled by Practice of Piety, such as the Nonconformist Joseph Alleine (1634–1668).Footnote 28 Bayly's book belonged to that category of devotional books that people read again and again during the course of their lifetimes, sometimes aloud, and whose prayers they used in their personal devotion.Footnote 29 These English readers were representative of a wide spectrum of religious convictions, ages, and social classes (lower class, middle class,Footnote 30 and nobilityFootnote 31).

On a couple of occasions Bayly's work became an issue in the controversy between advocates and adversaries of the movement of Puritanism.Footnote 32 In one example the book played a role in an extravagant account of a murder by Enoch ap Evan (c.1599–1633) from Clun, Shropshire, in 1633, who had previously been converted to Puritanism. In that year, he killed his mother and brother, who had tried to dissuade him from his Puritan convictions. After the murder, Enoch fled to a friend, from whom he borrowed Bayly's book. This entire event elicited a series of polemical pamphlets between advocates and adversaries of Puritanism.Footnote 33

There was further controversy in and around 1650 when opponents of the episcopate such as the Camden Professor of History at Oxford, Lewis du Moulin (c.1605–1680), rejected the authorship of Bishop Bayly, who by then had been dead for almost twenty years. Bayly had been accused of obtaining a manuscript from the widow of a Puritan minister, without paying for it. According to Du Moulin, Bayly had rewritten the text slightly and had published it under his own name. The Bishop of Bangor at that time, Humphrey Lloyd (1610–1689), however, rejected the accusation as being a lie from the Puritan faction and confirmed Bayly's authorship.Footnote 34

Second, Bayly's book was well-received in Britain, beyond England, as its popularity grew in both Scotland and Ireland.Footnote 35 It became known in the “New World” too, where both non-Puritan colonists in Virginia and Puritan colonists in Northumberland (Maryland) and Massachusetts owned copies of the book.Footnote 36 And to the East, Bayly's writing was also read by English-speaking communities on the European continent.Footnote 37

Dutch

In 1620, about eight years after the publication of the original, Bayly's book was translated into Dutch. Many aspects related to the production, circulation, and reception of the Dutch translation have been studied thoroughly, the results of which are published in a volume edited by W. J. op ’t Hof, A. A. den Hollander, and F. W. Huisman.Footnote 38

The Dutch translation was made by Everhardus Schuttenius, a student of theology from Zwolle, who brought a copy of The Practice of Piety back to the Netherlands from a study trip to Oxford. His translation was published after his ordination as a minister. He dedicated it to, among others, the Palatinate official Friedrich d'Orville (1590–1641), with whom he had come into contact at Oxford.Footnote 39 There is an interesting link back to Bayly because D'Orville educated the oldest son of the Elector Palatine, Frederick V (1596–1632), the “Winter King,” who married Elizabeth Stuart in 1613. And she was the sister of the Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, who Bayly had served as chaplain and who had died in 1612. The father of Elizabeth and Henry was James I, King of England.Footnote 40 This illustrates how the networks of Bayly and Schuttenius may have indirectly overlapped. As a minister, Schuttenius translated various devotional books and was a fervent advocate of the reformation of manners, particularly of the sanctification of the Lord's Day, ecclesiastical discipline, the repression of all remnants of Roman Catholicism, and religious education.Footnote 41

Around 1650, the Dutch translation of Bayly was ranked second for bestselling religious books, after the Geuzenliedboek (Songbook of the Geuzen Rebels, c.1574).Footnote 42 With a total of about 102,000 copies, the Dutch translation of Bayly was the most widely sold Reformed theological book in the seventeenth-century Republic.Footnote 43 The conclusion one draws from this is that the book had reached a status whereby it had become part of the basic inventory of any household or community. This is reinforced by a prescription of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1654 and which lasted until 1790—to provide every ship of the company with two copies of Bayly's work.Footnote 44

Several years earlier, in 1642, a revision of the translation appeared, spearheaded by the Utrecht professor of theology Gisbertus Voetius (1589–1676). Voetius had a student revise the translation, and he gave comments on certain passages in the footnotes.Footnote 45 In previous research I have compared the translation method of the editions of Schuttenius and Voetius.Footnote 46 Whereas both men left Bayly's argument intact, both adapted their translations to culturally specific or dogmatic elements, Voetius's more so than Schuttenius. A couple of examples follow that serve to illustrate this.Footnote 47 Please note that for quotations in Dutch (as for German quotations in the next section), an English translation is provided directly below each quotation.Footnote 48

ENG 1640, 225: Defend the Kings Maiestie, from all his enemies, and grant him a long life, in health, and all happinesse, to raigne over us. Blesse our gracious Queene Mary, Prince Charles, the Lady Mary, the Lady Elizabeth and her Princely issue.

NL 1640 [Schuttenius], 182: Beschermt zyn Conincklijcke Majesteyt voor alle zyn Vyanden, ende verleent hem een langh leven, dat hy in ghesontheydt ende ghelucksalicheydt over ons regieren mach: Seghent zyne Con. Majesteyt, den Prince Car olum [sic], zyn Conincklijcke ende Keurvorstelijcke ghenade van den Palts, ende zyn Conincklijcke Ghemael Elizabeth. De Hoogh-Mogende Heere Staten Generael. Den Doorluchtighen ende Princelijcken Helt Mauritium, de Heere Staten van Over-Yssel etc.

[Protect his Royal Majesty from all his enemies, and grant him long life, that he may rule us in health and happiness: Protect his Royal Majesty, the Prince Charles, his Royal and Electoral Majesty of the Palatinate, and his Royal Duchess Elizabeth. The High Majesty of the States General. The illustrious and Princely Lord Maurice, the Lord States of Over-Yssel, etcetera.]

NL 1642 [Voetius], 195–196: Seghent N.N. Hier kanmen met namen uyt-drucken de Overheden yeder van zijn lant en plaetse daer hy woonet: als by exempel, de Heeren Staten van dese Provincie, de Magistraet van dese Stadt, of van dese plaetse.

[Bless N.N. Here one can mention by name the authorities of each of his country and place where he lives: as for example, the Lords States of this province, the magistrate of the city, or of this place.]

In these sentences, which are part of a morning prayer, Schuttenius adopts the names of members of the British crown. Note the mention of Elizabeth Stuart and of Prince Palatine (Frederick V) (see above).Footnote 49 He also adds Prince Maurice of Orange and Overijssel, the states of the province where he was living. However, Voetius leaves it to the readers to fill in the political authorities of the country of their residence.

In the following example, in which the episcopal structure of the church is mentioned, it may have been more difficult for the Dutch Reformed translators, since they were advocates of a presbyterial governance structure.

ENG 1640, 225–226.: Direct all the Nobility, Bishops, Ministers & Magistrates of this Church and Common-wealth, to governe the Commons in true Religion, justice, obedience, and tranquillity.

NL 1640, 182–183: Regieret den Edeldom, Bisschoppen, Predicanten ende Magistraten van dese uwe Kercke ende Politie, datse uwe Volck in waerachtighe Religie, gerechtigheydt, ghehoorsaemheyt ende vreedsaemheydt regieren moghen.

[Govern the nobility, bishops, pastors, and magistrates of your church and police to govern your people in true religion, justice, obedience, and peace.]

NL 1642, 196: Regeert de Predicanten datse u volck in gerechticheydt ende gelucksalicheyt wel moghen regeeren: ende opsienders van dese uwe Kercke, dat door hare leere, vermaninge; goeden voortganck, ende exempel alle publijcke ende particuliere oeffeninghen der Godtsalicheyt in dese uwe gemeynte aengestelt ende gevordert moghen werden.

[Command the pastors that they may govern your people in righteousness and happiness: and overseers of your church, that through their teaching, exhortation, good progress, and example, all public and private exercises of godliness may be established and promoted in this your congregation.]

However, it can be observed that Schuttenius left the phrase on nobility, bishops, ministers, and magistrates of the church and commonwealth out, whereas Voetius more rigorously intervened in the text, eliminating all except “Ministers” (Predicanten). The reason for this will have been that he rejected episcopacy, as well as excessive interference of the political authorities in the church.Footnote 50 Furthermore, Voetius added a significant element in the admonition: that of the elders (opsienders).

Last, Voetius left out one passage on the last judgment, which Schuttenius had translated, because he considered this sentence doctrinally objectionable. Voetius justified his change in a note as follows:

ENG 1640, 82–83.: Christ shall rip up all the benefits he bestowed on thee, and the torments he suffered for thee.Footnote 51

NL 1640, 66: u Christus alle zyne weldaden aen u bewesen op-halen sal, de pynen die hy voor u gheleden heeft, de goede wercken die ghy ghelaten hebbet.

[Christ will remind you of all his benefits shown to you, the pains he suffered for you, the good works you have omitted.]

NL 1642, 73: u Christus alle zijne weldaden aen u bewesen op halen sal, *de goede wercken die ghy gelaten hebt.

[Footnote by Voetius:] Ick hebbe uyt-gelaten dese woorden des Autheurs: de pijne die hy voor u gheleden heeft: vermidts de selve seer duyster ende dobbelsinnigh zijn. Siet tot naerder verstant, de verklaringhe des Dortschen Synodi Anno 1619. over den tweeden artijckel der Remonstranten.

[Christ will remind you of all his benefits shown to you, *the good works you have omitted.]

[Footnote by Voetius:] I have left out these words of the author: the pain which he has suffered for you, since they are very obscure and ambivalent. See for further understanding the declaration of the Synod of Dort of 1619 about the second article of the Remonstrants.

Voetius removed the passage: “and the torments he suffered for thee,” as he regarded these as “very obscure and ambivalent,” and he refers to the pronouncement of the Synod of Dort (1618–1619) on the second article of the Remonstrants, in which the extent of Christ's atonement is discussed. Voetius most likely feared that the passage in question could suggest that Christ had not just sufficiently but efficiently died for all, an opinion that was rejected in Chapter Two of the Canons of Dort.Footnote 52

These comments by Voetius can be categorized as either analytical (making explicit, interpreting, honing, or elucidating) or evaluating comments. In the latter category, he especially criticized the exegetical underpinning of Bayly's assertions. For Voetius, several of these arguments have shortcomings because they cannot be derived explicitly from scripture, are speculative, or bear similarities with Roman Catholic superstition. Voetius deplored these weaknesses because for him the practice of piety was to be grounded on scripture and not, as he stated, on loose and uncertain concepts.

Changes were not only made by translators however, but by publishers too. These started and were evidenced in the edition published by Michiel de Groot in Amsterdam in 1669. In this edition (and in later editions by other publishers), Latin quotations, some of the Bible verses, and a passage on the differences between the doctrine of the apostles and of the Roman Catholic church were removed.Footnote 53

From the very outset, the Dutch translation was quoted and referred to by Dutch authors, particularly by reform-minded theologians such as Willem Teellinck, Voetius, Willem Sluiter, and Petrus van Mastricht. This occurred primarily because several of the book's topics appealed to them, including the delight of men after the reunion of body and soul on the day of resurrection, conversion, strict observance of the Sabbath, fasting, meditation, and morning prayer.Footnote 54

German

Reformed version

In 1627, about seven years after the first Dutch translation, parts of Bayly's Practice were published in a German version for the first time. The passages that address the Lord's Supper were added to a book on the same theme, written by Johann Jacob Grasser (1579–1627): Heavenly Soul Table (Basle).Footnote 55 A year later, the whole of Bayly's book was translated into German and was published by Ludwig König in Basle. Possible translators include the ministers Grasser and Wolfgang Mayer (1577–1653), the latter being a step-grandson of Martin Bucer (1491–1551).Footnote 56

Switzerland functioned as a port of entry for the German Reformed version of Bayly's writing. In 1630 Bayly's complete book was issued for the first time within the Holy Roman Empire (or, Old Empire). Two editions appeared, one in Basle and the other in Bremen. A year later, the unsold copies of the editions from Basle and Bremen were published by König in his store in Frankfurt. In Switzerland, Bayly's book was released thirty times during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 57 Another Puritan book—the collection of meditations by Joseph Hall, Art of Divine Meditation (1601)—was added to the German edition of Bayly, published by Samuel König in 1629 from Basle, as well as to many subsequent editions. Through this addition, the small number of meditations in Bayly's work were complemented by a collection of samples from that genre.

Bayly's book appears to have been popular among Reformed ministers and theologians in Germany, as requests were made in 1633 by many of them.Footnote 58 Also in 1633 several German Reformed theologians from the Palatinate and Wetterau requested the Church of Great Britain and Ireland to compile a compendium on the practice of piety from English devotional books. This was motivated by their assertion that the German translation of Bayly's book had produced substantial spiritual growth in numbers of people. A compendium would therefore serve to direct pastors and theologians away from controversy toward love. The request was approbated by Frederick V, Elector Palatine.Footnote 59 The observation made in this article—that the networks of Bayly and the Dutch translator Schuttenius merged somewhat through the royal houses of England and the Palatinate—has made one thing clear: the request by these ministers reinforces the idea that the Palatinate functioned as a hub for the dissemination of English devotional writings to the continent.

It was the Scottish theologian John Dury (1596–1680) who was the main advocate for a union between Calvinists and Lutherans, having made lifelong travels through Europe to advance his scheme. He summarized what many felt to be true: that Bayly's book was one of the works in which the fundamental articles of faith were clearly and efficiently presented.Footnote 60

Lutheran version

The year 1631, however, marks a turning-point for the German translation of Bayly. In that year, a Lutheran adaptation was published by Johann and Heinrich Stern in Lüneburg, a city in Lower Saxony.Footnote 61 In the translation, some passages were reworked for theological reasons, an example of which are the following sentences on good works:

ENG: But he should know, that though good works are not necessarie to justification: yet they are necessarie to salvation.

GER: Aber da muß man wissen: Ob wol die guten Wercke nit nötig sind zu unserer Rechtfertigung, daß wir doch notwendig uns deroselben befleissen müssen, wenn wir gedencken im Stande der Rechtfertigung zu bleiben, und einmal an jenem Tage in der That selig werden wollenFootnote 62

[However, we have to consider this: although good works are not necessary for our justification, we must necessarily be diligent in them if we want to remain in the state of justification and if we truly are to receive salvation on that day.]

In the translation, the assertation that good works are necessary to salvation, has been rewritten: “we must necessarily be diligent in them if we want to remain in the state of justification and if we truly are to receive salvation on that day.” Apparently, from a Lutheran perspective it was important, on the one hand, to soften the necessity of good works for salvation, but on the other, to make explicit the possibility of falling from the state of justification.

Other passages were adapted too. The polemical tone against the Roman Catholic Church was weakened, and the names of Calvinistic theologians (John Jewel, John Calvin, and William Perkins) were omitted.Footnote 63 The following two reasons may account for these changes: First, polemics against Roman Catholicism were contradictory to an irenic stance, and second, Calvinist theologians were not considered authorities within Lutheranism.

As publishers of the German Lutheran versions, the Stern brothers from Lüneburg were directed by a nobleman at the Leipzig Book Fair to a minister who had translated Bayly and Sonthom's Golden Jewel.Footnote 64 This man was, most likely, Justus Gesenius (1601–1673), who served as a minister in several places in Lower Saxony.Footnote 65 In his influential catechism, as well as in other publications, the influence of Bayly can be traced in, for example, the necessity of household catechetical instruction by the father, as well as the topics of prayer, the Lord's Supper, and Sunday sanctification. Furthermore, in the Lüneburg Bayly edition of 1631, two books written by Gesenius were added as complements. These were On True Christian Devotion and Small Catechism School. All these data strongly support the assumptions by Hans Leube and Edward C. McKenzie that Gesenius was the Lutheran adaptor of Bayly and Sonthom's Golden Jewel.Footnote 66 Gesenius may have become acquainted with the work of Bayly and with Sonthom's Golden Jewel via his irenic Lutheran professor in theology at Helmstedt, Georg Calixt (1586–1656), who had recommended Bayly and Sonthom.Footnote 67 Incidentally, just as with the German Reformed version, Hall's Art was added to the German Lutheran translation from the third Lüneburg Bayly edition (1633) onward.

The importance of Bayly's writing in the county of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (part of Lower Saxony) is seen from a reference in a book published in 1650 by the Helmstedt professor Konrad Hornejus (1590–1649). In this writing, Hornejus defended the opinion of the Helmstedt theologians about faith and good works. To legitimize his point of view, Hornejus referred to Johann Gerhard's School of Piety (1622–1623) and to Johann Arndt, Sonthom, and Bayly. According to Hornejus, these books were well-known in the county of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and (just like the Helmstedt theologians) teach that a faithful Christian should avoid great and known sins by living in the fear of the Lord if they want to attain the salvation that has been promised to the baptized child.Footnote 68

In 1634, another Lutheran revision of Practice of Piety was published, this time by Caspar Dietzel at Strasbourg, a city that, in those times, belonged to the Old Empire.Footnote 69 In particular, the sections about predestination and the Lord's Supper had been changed. The edition consisted of an approbation by the ecclesiastical authorities of Strasbourg, which may have furthered substantially the acceptance of Bayly's book within Lutheranism. This approbation might have been indebted to Strasbourg's highest church official, the moderator (Kirchenpräsident) and professor of theology Johann Schmidt (1594–1658), because Schmidt had recommended Bayly's book in his foreword to a catechism by Justus Gesenius. Another reason might be that Schmidt, in his sermons, drew from Bayly's prescriptions pertaining to behavior before, during, and after Sabbath worship. Schmidt may (as was assumed by Johannes Wallmann) also have written the preface to the book. Whether or not the Strasbourg theologian had become acquainted with Bayly's book during a study trip to England, the ongoing influence of Bayly on Schmidt can nevertheless be seen in the content of his sermons, where he borrows material from the Welshman.

Overall, Bayly's book was published seventy-one times in German, the last time in 1743. New editions appeared at intervals of less than two years, and most editions were published in Germany (thirty-eight), followed by Switzerland (thirty) and the Netherlands (three). The place of publication of one edition remains unknown.Footnote 70 While many editions were printed in Lutheran towns (Lüneburg, Danzig, Strasbourg, Nuremberg, Wolfenbüttel, Frankfurt, Leipzig), the number of Lutheran editions was significant.Footnote 71 From a calculation by Lehmann (see the section “Lewis Bayly and His Practice of Piety”) conducted in 1980, it turned out that the German Bayly translation holds second place on the list of German devotional bestsellers from 1600 to 1750,Footnote 72 after Arndt's books on true Christianity. Bayly's book—with its systematic and detailed prescriptions for daily sanctification—most likely filled a gap in the German-speaking countries by supplementing the native devotional books of Arndt and others, which were more focused on the inner pious life of the soul.Footnote 73

Reception by Lutherans in the Old Empire

Many publications by Lutherans contain recommendations, references to, paraphrases of, and/or quotations from Bayly's book. A writing in which many sections are borrowed from Bayly's Practice is Ludwig Dunte's Exercise of Christianity (1630). Udo Sträter has already hinted at the “unmistakable relationship” between the purpose and content of Dunte's and Bayly's books,Footnote 74 but this extends beyond what could be termed a relationship. A cursory comparison reveals how Dunte borrowed the content of many sections from Bayly, even though Dunte revised the text by abbreviating, rewording, adding, transposing, and summarizing it. The following example from a prayer for Sunday morning illustrates Dunte's translation strategy:Footnote 75

Bayly 350–351: Ich weiß wol, lieber Herre Gott, vnd gedencke daran mit zittern: daß vast der dritte theil deß guten samens in böß erdreich fället (Matth. am 13. vers. 4. &c.). Laß derowegen nicht zu, daß mein hertz gleich seie einem gebahnten wege, der, von wegen seiner härte vnd vnverstands, den guten samen nicht annimpt, vnd der böse feind darnach komme, vnd denselben hinweg raffe. Daß ich auch nicht sey wie ein steinichter acker, oder nur auf eine zeitland den samen annemme, zur zeit der verfolgung aber abfalle: noch wie ein dörnichter acker, auf dem die betrügliche reichthumb dein Wort ersticken. Sondern daß ich gleich sey einem fruchtbaren erdreich, vnd dein Wort höre, vnd behalte in einem feinen reinen hertzen, vnd frucht bringe, nach der maß, wie es deiner weißheit gefällig, vnd mir zu meiner seelen trost nutzlich sein wird. Oeffne die thür deines Worts deinem diener, den du vns zuschickest, auf daß vnsere augen aufghetan, vnd wir auß der finsternuß zu dem leicht, (Act. 26. v. 18.) auß dem gewalt des Satans zu dir, geführet werden: zur vergebung der sünden, vnd zu der gemeinschaft deren, die durch den glauben in Christo JEsu geheiliget seind.

[I know well, dear Lord God, and remember it with trembling: that nearly the third part of the good seed will fall into the evil kingdom of the earth [Matthew 13:4, etcetera)]. Therefore do not let my heart be like a paved road, which, because of its hardness and lack of understanding, does not accept the good seed, and the evil enemy comes after it and snatches it away. Nor let me be like a stony field, or that I receive the seed only for a season, but fall away in the time of persecution: nor like a thorny field, where the deceitful riches choke thy word. But may I be as fertile soil, and hear thy Word, and keep it in a tender and pure heart, and bring forth fruit according to the measure that shall be pleasing to thy wisdom, and profitable to me for the consolation of my soul. Open the door of thy word unto thy servant, whom thou sendest unto us, that our eyes may be opened, and that we may be led out of darkness into light, [Acts 26:18.] out of the power of Satan unto thee, for the remission of sins, and unto the fellowship of them which are sanctified by faith in Christ JESUS.]

Dunte 169–170: so laß den Saamen deines Worts nicht auff einen b[ö?]sen Acker fallen, nicht auff dem Wege, denn also möchte das Hertz, wegen gebahneter Härtigkeit den Samen nicht annehmen, biß der Böse komme, und ihn wegnehme, nicht auff dem Felsen, daß ich nicht eine Zeitlang gläube, und zur Zeit der Anfechtung abfalle, nicht unter die Dörner, damit dieselbe das Wort, wegen der Sorge dieser Welt, und betrieglichen Reichthum, nicht ersticke, sondern auff ein gutes Land, damit ich dein Wort in reinem Hertzen auffnehme, und Frucht bringe in Geduld; Gib deinem Worte Krafft, daß es nicht leer zu dir komme, laß mich dadurch erfüllet werden mit Erkäntnüß deines Willens, in allerley geistlicher Weißheit und Verstand, laß mich darin, als in einem klaren Spiegel, dein Ebenbild sehen, damit ich in dasselbe möge verkläret werden, von einer Klarheit zur andern, und zu diesem Ende gib deinen Diener, mit freudigen Auffthun seines Mundes, dein Wort zu reden, als welchen du zu uns gesand hast, unser Augen auff zu thun, daß wir uns bekehren, von der Finsternüß zum Liecht, und von der Gewalt des Satans, zu GOtt, zu empfangen Vergebung der Sünde, und das Erbe, sammt denen, die geheiliget werden, durch den Glauben an dich

[Do not let the seed of thy word fall on an evil[?] field, not on the path, for then the heart, because of its hardness, will not accept the seed until the Evil One comes and takes it away, not on the rock, so that I will not believe for a while, and fall away in time of temptation, not under the thorns, lest the same choke the word, because of the cares of this world, and the deceitful riches; but upon a good land, that I may receive thy word in a pure heart, and bring forth fruit in patience; Give strength to thy word, that it come not to thee void; let me thereby be filled with knowledge of thy will, in all spiritual wisdom and understanding; let me see thine image therein, as in a clear mirror, that I may be transfigured into it, from one clearness to another; and to this end give thy servant, with the joyous opening of his mouth, to speak thy word, as whom thou hast sent unto us, to open our eyes, that we may turn from darkness to love, and from the power of Satan, unto God, to receive forgiveness of sins, and the inheritance, with them who are sanctified by faith in thee.]

Both passages use the parable of the sower, but whereas Bayly uses the images of the parable, Dunte has expounded them. Furthermore, Dunte adds to Bayly by writing a prayer to give power to the Word and to fill the believer with it.

In other places, Dunte integrated passages from Bayly's book into a Lutheran framework. An example of this can be seen in the addition of Martin Luther's hymnbook:Footnote 76

Bayly 294–295: ZU nachts, wann es schlaffens zeit ist, so lasse dein haußgesind zusammen kommen: läse ein capitul in der Bibel, wie oben angeregt: vnd singe ein psalmen, wie vnser Herr Jesus auch gethan hat.

[At night, when it is time to sleep, let your household come together: read a chapter of the Bible, as suggested above, and sing a psalm, as our Lord Jesus also did.]

Dunte 357–358: Hat ihn GOtt zum Haußvater, oder zur Haußmutter gesetzet, so muß er sich hie abermahl, wie am Morgen geschehen, des Göttlichen Befehls, und seiner Gebühr erinnern, mit den Kindern und dem Gesind, ein Capitel, oder was mehr aus der Bibel lesen, einen geistlichen Lobgesang oder Psalm aus des Herren D. Lutheri, des rechten Künstlers in diesem Werck, Gesangbuch, singen.

[If God has appointed him father or mother of a household, he must at this time, as he did in the morning, remember the Divine command and his duty, read a chapter or more from the Bible with the children and the servants, sing a spiritual hymn or psalm from Dr. Luther, who is the true artist in this respect, from his hymnal.]

It is possible that Dunte became acquainted with Bayly's work during his study trip through the Netherlands, England, and France, during which time he studied at the Bodleian Library in Oxford for eighteen months. But, as he acknowledges in the preface, Dunte not only used Bayly, but other sources as well, including German, French, and English sources.Footnote 77

Recommendations, references to, paraphrases of, and/or quotations from Bayly's book can also be found in writings by the main pastor and superintendent of Halle an der Saale, Arnold Mengering (1596–1646), the politician Michael Moscherosch (1601–1669), the minister Gottfried Olearius (1605–1685) from Halle, and the Rostock theologian Theophil Großgebauer (1626/1627–1661).Footnote 78

Among the quotations from Bayly's book, prayers appear frequently. In one example, in a book on the Lord's Supper written by Johann Rittmeyer (1636–1698), a minister at Helmstedt. Rittmeyer complained in his preface that many people read Reformed devotional writings because of the lack of Lutheran ones. Yet he himself quoted Bayly. And so quoting from a book that had been written by a Reformed author seems to have been the “least worst” option for him.Footnote 79 Other examples of the adoption of prayers from Bayly are the prayer book by the Lüneburg printer Michael Cubach,Footnote 80 and that of the Stuttgart theologian Johann Christian Storr (1712–1773) in 1757. The latter quoted several morning and evening prayers from Bayly in his Christian House Book for the Practice of Prayer (1757), together with prayers of Lutheran authors such as Caspar Neumann, Johann Arndt, and Johann Habermann.Footnote 81

The popularity of Bayly's book can be proven not only by the number of quotations from it, but also by the fact that it was included in a list of recommended books presented by Ernst the Pious (1601–1675), Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, to his ministers and teachers in 1660. The list consisted of the works of Luther, Arndt, the Gotha chaplain Salomon Glassius (1593–1656), and Bayly's book.Footnote 82 The retrospective bibliography of seventeenth-century printings of the German language area, the VD17 catalogue, shows that several clerics and noblemen, including those from the house of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (which was close to Pietism) were in possession of a copy of Bayly's writing.Footnote 83

Practice of Piety exerted considerable influence on the biographies and works of leaders of the movement of Pietism—a movement that was characterized by, among other hallmarks, its establishing of devotional gatherings or conventicles (collegiae pietatis).Footnote 84 An expert on this movement, Martin Schmidt, asserts, “Bayly was the preferred instigator of German Pietism.”Footnote 85 It may have been via the Strasbourg professor Johann Schmidt, the initiator of Lutheran Pietism in the Old Empire, that Philipp Jakob Spener (1635–1705) became acquainted with Bayly's writing. The book had a strong impact on Spener, both during his conversion and throughout the rest of his life. He ascribed his discovery of the vanity of the world, and his loosening from it, to his reading of, among others, Bayly. Bayly's meditations on the blessed state of the believers and on the misery of unbelievers in life, at death, and after death, touched Spener, and he even put a part of these meditations into verse. In addition, Spener may have been motivated by the reading of Bayly describing a longing to die, which he, by his own testimony, experienced when his grandmother died. Moreover, it may have been due to his reading of Bayly that Spener fasted once a week during a year of his studies in Strasbourg. Last, throughout his whole life, Bayly's ideas may have affected Spener's opinions about the sanctification of life in general as well as of Sunday, about worldly pleasure, the office of a minister, and mystical union with Christ in particular.Footnote 86 It is illustrative of the high esteem that Spener held for Bayly's writing that he chose it as one of the books to be read at the conventicle that he founded in 1670 in Frankfurt.

Later on, however, Spener became more critical of Bayly's book (as well as other English devotional writings), which he considered mixed the law with the gospel and justification with sanctification. For this reason, he gradually turned toward Arndt's main book for inspiration. Despite this, however, Spener continued to recommend several English devotional writings, and Bayly's writing was first and foremost among these.Footnote 87 Spener continued appreciating these books because of their call to repentance and their prescriptions for the sanctification of life. He argued that Lutheranism and Calvinism differed on doctrine but saw almost eye to eye on the practice of piety. Therefore, he restricted his recommendation of Bayly's book to those Lutherans who were well-grounded in doctrine.Footnote 88

Like Spener, his pupil August Hermann Francke (1663–1727), who is famous for the foundations he opened in Halle, was also affected by Bayly's book. During his youth, he read Arndt, Bayly, and Sonthom, and he claimed that he read Bayly's book and Dunte's work after every communion, with much blessing. Francke was influenced by Bayly's thoughts concerning meditation, sanctification of Sunday, worldly pleasure, and ministry.Footnote 89 Among Lutheran theologians, the popularity of Bayly's book abided, and can, among other influences, also be traced back to the Württemberg Pietist Johann Albrecht Bengel (1687–1752).Footnote 90

Whereas many Lutherans seem to have assessed Bayly's book in a positive and even appreciative way, others were exceptionally critical of it. Beginning in 1654, a number of theologians, such as Johann Hülsemann (1602–1661) from Leipzig—who called Bayly and Sonthom Schmadderer (scribblers), an invective used for Anabaptists; Spener's brother-in-law Joachim Stoll (1615–1678) from Rappoltstein; and Georg Christian Eilmar (1665–1715) from Mühlhausen, criticized Bayly's book for its mingling of law and gospel, nature and grace, justification and sanctification, and repentance and faith.Footnote 91 In the works of Bayly and Sonthom, they saw “neither law nor gospel, neither grace nor nature, neither regeneration nor justification, neither repentance nor faith distinguished.”Footnote 92

Conclusion

From the data collected, some general conclusions can be drawn on the circumstances under which Bayly's book and its contents were welcomed or not—how they were appropriated, decontextualized, and recontextualized, and by what kind of people. First and foremost, the book was highly popular for a sustained period of time. Evidence of this is partially demonstrated by the number of languages into which it was translated. The Practice of Piety attained a high number of editions throughout the whole of Europe and beyond. It found readers among different confessional communities and social classes, and it often belonged to the basic inventory of households and even trading ships. Moreover, the book was translated into languages with minority status, it stirred the realm of polemics, and it found its place among books recommended for reading.

The worldwide popularity of Bayly's book can be explained thus: first, by its catholic character, which came into being both through borrowings from Pre-Reformation sourcesFootnote 93 and by the fact that Bayly's opinions, as expressed in his book, did not fit entirely in any one camp. On the one hand, Bayly, like the Puritans, held strict views on keeping the Sabbath holy, and he firmly believed in predestination. On the other hand, he urged conformity to the established church, defended the practice of private confession to a priest and the ringing of church bells on Sunday, and condemned those who would not kneel or take their hats off in church.Footnote 94 This may have made his book attractive to a wide range of confessions and traditions, especially those who could adapt to fragments of worship that deviated mildly from their own views. A second plausible explanation for such popularity may, as has been suggested by Ryrie, be laid at the door of “sheer, safe comprehensiveness.”Footnote 95

The issue around whether Bayly's book was welcomed or criticized by learned people seems to have been mainly dependent on the question about whether there was a match between Bayly's urge for sanctification directed to human will and reason, and the religious stance of a reader. Sympathy was received for the book especially among reform-minded theologians, such as Voetius, Schmidt, and Spener, but Lutheran theologians who emphasized justification deplored its lack of attention toward the heart and emotions.

In addition to theological affinity, other determinants affected the production, circulation, and reading of Bayly's book. It became available in cheaper formats and smaller sizes. In addition, its controversial standing, and the involvement of higher clergy as editor (Voetius), translator (Gesenius), and approbator (Schmidt), all influenced its successful dissemination. Furthermore, its inclusion in a list of recommended books (Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Dury) appears to have stimulated further interest.

Bayly's book moved beyond England and came into translation or print via different channels. Examples include study trips (Schuttenius), references (the noble men who introduced the Stern brothers to a minister who had translated Bayly into German), and the networks of Bayly through the court of England and the Palatinate.

The publishing of Bayly's writing in English (or other language) was done so through appropriation and was never simply a process of reproduction or transference into the other language. For example, it was appropriated either as a Puritan book or a non-Puritan book (England), or as a work secondary to Lutheran catechisms (Old Empire: Spener). A somewhat “modern” critical edition was created by Voetius, who commented in footnotes on passages of Bayly, thus demonstrating differences between his own opinions and those of Bayly.

Appropriation not only took place in the production of editions of Bayly's book but also in the reception of them. Internationally, most readers seem to have found certain topics appealing, such as the sanctification of Sunday, catechetical instruction, and preparation before and contemplation after the Lord's Supper. In addition, it was often the prayers that were borrowed from Bayly's writing. The suggestion therefore is that the readers considered these topics and sections an important addition to their native devotional literature.

Appropriation of Bayly's book sometimes meant outright adaptation, especially if the writing was translated into a different language or for a different confessional community. The examples of the Dutch and the German Lutheran versions by both Schuttenius and Voetius show how translators dealt in various ways with cultural and doctrinal differences between the source culture and the target culture. Whereas Schuttenius aggressively reinterpreted text in his decontextualizing and recontextualizing of cultural elements, Voetius and the German translator went even further in adapting doctrinal passages. It was also not just translators who changed the contents of the book, but publishers too, for example, by abridgment. This occurred in the Dutch editions by, among others, de Groot. Moreover, not only was the content of Bayly's book adapted, but its function or purpose could also shift away from its original state.

In addition to strategies linked to decontextualization and recontextualization, there were other adaptations that took place, which may not have been caused by cultural or doctrinal differences. Examples of these shifts can be seen in the combining of passages from Practice of Piety with other books, such as Grasser's Heavenly Soul Table or Hall's Arte of Divine Meditation (German translation), or referring to and quoting or paraphrasing from Bayly's writing in other books (German writings). Finally, Bayly's book, as a whole or in its parts, was rendered from prose into poetry (Spener) in a process of transfer called intermediality.

Bayly's book was in the possession, and read by a variety, of social classes, from the poor (Bunyan's wife), the middle class, and the nobility. For many, the attraction seems to have been the daily reading or perhaps the model prayers (English readers). For some, Bayly's writing was instrumental for their conversion (Bunyan, Spener) while for others it was invaluable for their deathbed reading (Joseph Alleine).

Taking all these considerations into account, one may conclude that the state of the art of research as it relates to the production, circulation, and reception of Bayly's book is not equivalent in each language area. In the English, Dutch, and German language areas, much is known about the acceptance, or criticism, of Bayly's writing as well as about how and by whom it was appropriated. Far less is known regarding these issues for other language areas, such as the Czech, Polish, Rhaeto-Romance, and Korean. Further research into the production, circulation, and reception of Practice of Piety in these lesser-known areas should be carried out using the same thorough research carried out into the Dutch- and German-language areas as a model. Such research requires skills, for example, in languages, and should ideally be performed by multidisciplinary international research teams. The comparison should not be limited to the source text and translations, but also the illustrations in different versions because this will reveal and trace shifts in how the book was experienced by different readers. Overall, in comparison to other dogmatic works, a devotional book such as Bayly's reveals how relatively few adaptations were required to translate the book to suit a different confessional community. Further research is also needed to determine which parts of Bayly's writing deserved reworking and in what circumstances. This future research should focus on investigating not only shifts in the text, but also the adaptation of images.Footnote 96 This could be extended to research into material aspects such as book bindings. The resulting cues would be invaluable in understanding more about how people used the book and what role it played in their lives.Footnote 97 In the fullness of time these initiatives will advance our knowledge of the transfer and translation of religious literature in early modern times toward a more appropriate theoretical framework as it affects the study of cultural transfer and cultural translation in general.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Dr. Scott Dixon, Drs. Frans W. Huisman, Prof. Dr. Alec Ryrie, and Dr. Forrest C. Strickland for their comments on earlier drafts of this article; to Alexander Thomson and Piet de Kock for correcting the English; and to Eva van Dam for correcting the bibliographical references.