In the UK, a typical National Health Service (NHS) mental health service for older adults will usually accept referrals from a wide variety of sources. Healthcare professionals in primary care regularly seek advice about patients with dementia and about depression and psychosis in later life. Staff in secondary care settings routinely need advice and support for older patients with delirium (Reference Scott, Sorinmade and BeckettScott et al, 2005). Increasingly there is also a demand for confirmation of specialist decisions about capacity and competence across a wide range of arenas, including financial issues and personal care.

A variety of national publications have been influential in this area. The recent clinical guidelines for dementia from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006) encourage a ‘single point of referral for all people with a possible diagnosis of dementia’ (p. 4) and seek to support ‘coordinated delivery of health and social care services’ (p. 22). A report from the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness recommends that greater emphasis be given to risk management in older people's services (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 2006: p. 9).

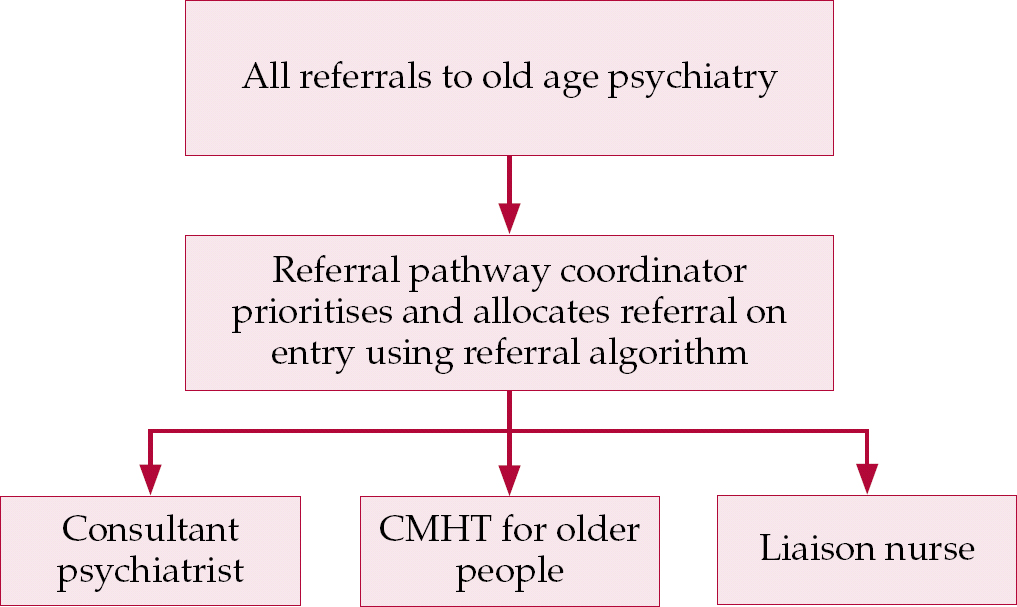

This article describes the development and introduction of a referral management system over a period of 3 years (from 2003 to 2006) that allows prompt and accurate identification of patient need and a preliminary assessment of risk. The system rapidly became established as a core component of mental health services provided locally in Bridgend in South Wales (Fig. 1). This process strives to be compatible with most aspects of the current modernisation agenda, and we are proposing that similar systems would prove useful more widely across the NHS. Several strengths of the model are described as well as some weaknesses and potential pitfalls.

Fig. 1 Outline of the single point of referral in Bridgend, South Wales.

Historical perspective

In 1992 psychiatric referrals concerning older adults in Bridgend were effectively routed through a single point of access. The service was led by a single consultant in old age psychiatry, working with one medical secretary out of an office in a large Victorian psychiatric hospital. However, by 2002 an expansion of local services and increasing demands for a widening range of complex treatments in the community had significantly fragmented this focus.

The many different healthcare professionals seeking advice from or wishing to make a referral to the mental health service for older adults were faced with a choice of referral options. Contact could be made through the mental health out-patient clinics or through the community mental health teams, or directly to one of two consultants in old age psychiatry. Several members of clerical and medical secretarial staff attempted to triage referrals arriving by a variety of routes. It had become possible for two (or exceptionally three) different responses to be made to a single referral, relayed by telephone, confirmed by fax and followed up by a letter sent in the post.

This model of referral management was felt to have become inherently inefficient. In general terms, a mental health response to any given referral is heavily dependent on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of information supplied by the referrer. In practice this is highly variable, a problem compounded by missing or unreliable information – a situation sometimes described as ‘evidentiary uncertainty’ (Reference Dixon and OyebodeDixon & Oyebode, 2007). The existing system contained no real incentive for routine investigation or ‘detective work’ into the referrals received each day. The absence of a systematic approach predisposed to a rather arbitrary prioritisation, often influenced more by the availability of mental health staff than actual patient need.

Similarly, there were only limited opportunities for the routine collection and analysis of details about referrers. The value of collecting information about referral patterns and attempting to identify trends over time had been overlooked. Perhaps most important of all, there remained an unacceptable governance risk involved in a service in which clinical decisions about patient need and subsequent allocation for assessment were delegated to secretarial or administrative staff.

We felt that a different approach was needed. There are several models of referral management, for example the traditional consultant-led system just described, the ubiquitous team-based weekly allocation meeting and the more recently established administrative referral management centres (Reference Davies and ElwynDavies & Elwyn, 2006). The advantages and disadvantages of each model were thoroughly considered (Table 1). None of the models adequately met the local service needs and a different and innovative method of working during business hours (Monday to Friday) was developed. We called this model ‘clinician-led referral coordination’.

Table 1 Some advantages and disadvantages of common referral management models

| Referral management model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Consultant-led referral system | Potential for prompt response | Demanding/expensive in senior medical staff time Biased towards medical model |

| Weekly allocation meeting | Multiprofessional approach | Requires parallel system for emergency/urgent referrals Team composition and availability of staff may unduly influence allocation |

| Clinician-led referral coordination | Equitable Led by patient need Encourages emergency/urgent response Promotes partnership working |

Requires support of senior health and social work staff Limited to working week – complementary on-call/duty/crisis service needed for out of hours |

| Referral management centre (administrative) | Consistent collection of minimum data-set | No attempt to identify priority or degree of urgency |

Theoretical aspects

The need to resolve the inefficiencies in the existing service while at the same time maintaining high-quality patient care and offering substantial improvements in care for a relatively small investment is reminiscent of complex real-life problems originally described by Reference Rittell and WebberRittell & Webber (1973) as a ‘wicked problem’ (Wikipedia offers a useful definition). The adjective ‘wicked’ denotes that the problem is difficult rather than bad or evil.

Wicked problems

Early descriptions of the features of a wicked problem have been expanded by Reference ConklinConklin (2006). The process of redeveloping and implementing a set of referral management protocols relevant to modern mental health practice provides a number of illustrative examples.

‘You don't understand the problem until you have developed a solution’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 14)

This is perhaps the most fundamental issue. In our case, at the start of the initiative, financial constraints allowed sufficient funding for just one new member of staff with mental health training – the idea of a central single point of referral actually arose more from the need to share the available resources equally and fairly between each of the community mental health teams than the need to manage referrals efficiently. However, once the idea of a referral coordinator had been agreed, our attention then quickly turned to the problem of developing an appropriate referral algorithm to support this role.

‘Wicked problems have no stopping rule’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 14)

There is no end to the sequence of referrals to mental health services. Some degree of referral management is always required, and whether this is formally controlled and reviewed or handled in an ad hoc manner is largely dependent on local circumstances.

‘Solutions to wicked problems are not right or wrong’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 14)

Conklin describes solutions as ‘good enough or ‘not good enough’. In our case, we have made changes to our referral algorithm since it was originally written – the intention was to further improve the document, which had originally been ‘good enough’, to allow the referral coordinator to take over routine management of referrals into the service.

For example, we regularly receive a small but significant number of referrals where an important concern is the effect of a mental disorder on the patient's ability to drive safely. In old age psychiatry at least, this has potentially serious consequences and a new heading (‘Driving licence assessment’) has been added to the list of reasons for referral, to give this need a little more emphasis.

‘Every wicked problem is essentially unique and novel’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 15)

There are significant differences between referral patterns in old age psychiatry and those in general adult psychiatry which usefully illustrate this aspect. The algorithm that we developed is relevant to the local mental health service for older adults in Bridgend. It is not necessarily relevant even for equivalent services in neighbouring local authorities. Although the general principle that patients should be seen according to need rather than according to the availability of staff will still apply, different local services will need their own (‘unique’) versions of referral management protocols.

‘Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one shot” problem’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 15)

Another key concept – our equivalent of the ‘one cannot build a motorway to see how it works’ – was taking the leap of transferring responsibility for routine management of referrals to the referral coordinator. Although this was done in stages (see below), once the process started there has never been any real likelihood that it would be stopped. A much clearer understanding of the importance of thorough detective work has developed over time, and opportunities to use the referral algorithm and the referrer database in a wide variety of different educational and management settings have further reinforced the value of the system.

‘Wicked problems have no given alternative solutions’ (Reference ConklinConklin, 2006: p. 15)

One further principle of clinician-led referral coordination is the notion that specialty staff should take responsibility for specialty decisions. Prior to this initiative, an analysis of the local consultant-led referral system had identified one anomaly in particular. In this model, the health professional or individual making a referral for psychiatric advice was (implicitly) expected to accurately identify the need and the priority of any given clinical situation in the referral – as described above, little allowance was made for coherent specialist input into risk assessment, allocation or delegation. In terms of quality assurance or clinical governance, when is it appropriate for a non-specialist (who has identified the need to seek further advice in a specialist area) to direct the specialist opinion (even if this is done unintentionally)?

This is an important aspect of mental health referrals that will obstruct the widespread implementation of the ‘choose and book’ system in England in its current form. However, this referral model is consistent with several influential publications (notably Losing Time ( Audit Commission, 2002) and Avoidable Deaths (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 2006)) and other national guidance such as the recent Referral Management Principles (British Medical Association, 2007).

Advantages of the clinician-led model of referral coordination

Consistency

The formation of an algorithm incorporating the most common reasons for a referral into old age psychiatry ensures that a high degree of consistency and equitable service delivery is sustained across the Bridgend area. This should reduce the amount of variation in the patient journey from point of referral to the mental health service response. Adopting a collaborative approach, the algorithm was developed over several months by all members of the multidisciplinary team with full representation from primary and secondary care, including local authority, administrative and management staff. The trust's information technology department was also consulted for advice on establishing an electronic referral allocation system.

A pilot period was felt to be essential to establish local effectiveness and identify unforeseen problems. After a 2-month period during which only hospital liaison referrals were processed using the new system, it was progressively rolled out into primary care, involving two new general practice surgeries every 2 weeks. This allowed for vigorous promotion of the new single point of entry and facilitated the opportunity for feedback. It is notable that, to the best of our knowledge, no adverse patient events were encountered during the roll-out period.

The referral algorithm guides the coordinator towards determining the most appropriate priority (Box 1) and allocation, thus supporting risk assessment on entry – a good referral sending the right patient to the right part of the service at the right time (Reference Davies and ElwynDavies & Elwyn, 2006).

Box 1 The prioritisation structure

-

• Highest-priority referrals (e.g. self-harm, suicidal intent, overt aggression) are seen within 24 h

-

• Urgent referrals (e.g. severe carer strain, resistive aggression, wandering) are seen within 2 working days

-

• Routine referrals (e.g. capacity, diagnosis, placement, carer support) are seen within 10 working days in the community, within 5 working days in secondary care, and within 4–6 weeks in clinics

The investigative process

Over time, experience has shown the central value of the investigative component of the referral coordinator's function. Frequently, significant and essential information that will establish a comprehensive referral is available from other agencies, and its collection and interpretation demands a continuous office presence. This is unlikely to be an option for medical staff or community-based nursing colleagues that run other referral management models. This collation of information by the referral coordinator will reliably identify many of the most complex cases, which in turn allows for a more informed process of delegation to available staff. This is entirely consistent with the recommendations of the New Ways of Working project for psychiatrists (Department of Health, 2005).

Typically a referral may not make clear what the referrer is actually seeking: ‘Confused, please arrange out-patient appointment’ seems to be a straight forward request for diagnosis, but it may conceal many issues. Does the patient live alone? If so, how will they remember an appointment? Are they coping with everyday tasks or putting themselves at risk? Further information is invariably needed for effective and safe prioritisation and allocation of the referral.

Time and again the detective role of the referral coordinator proves invaluable, providing as detailed and accurate a picture as possible by communication with any other professional agencies involved. Such a referral system not only demands successful partnership working and helps break down barriers between organisations but also acknowledges the importance of lay opinion. Social networks, particularly relatives and friends, frequently can play a significant role in influencing whether a person with mental health problems seeks medical advice preceding psychiatric referral (an area explored by Reference Owens, Lambert and DonovanOwens et al (2005) in a qualitative study looking at help-seeking prior to suicide).

Collation of all the available information and concerns allows for a more thorough preliminary risk assessment by the referral coordinator. An identification of risk by anyone (social worker, district nurse, care staff, etc.) may influence outcome once subject to the clinical interpretation of the referral coordinator, as the following fictional but typical case studies demonstrate.

Case study 1: Community referral for an ‘urgent’ domiciliary visit

Information from general practitioner:

-

• 89-year-old Mrs Z is confused

-

• Wandering ‘all the time’

-

• Lives alone, no immediate family or support.

Information obtained by referral coordinator from social worker:

-

• Mrs Z is disoriented with regard to time

-

• Going to church every day believing it to be a Sunday

-

• Finds her own way home

-

• Self-caring, coping, no immediate risks evident.

Referral downgraded by coordinator to ‘routine’ and initially allocated to the community mental health nurse.

Case study 2: ‘Routine’ liaison referral

Information from ward doctor:

-

• 70-year-old Mr X is presenting with forgetfulness

-

• ‘Please give opinion’.

Information obtained by coordinator from nursing staff:

-

• Mr X was admitted having taken too many tablets – this was assumed to be an accidental consequence of his poor short-term memory.

Information obtained by coordinator from home care organiser involved with Mr X:

-

• Mr X had not been eating and had been neglecting himself for some time

-

• Mr X frequently told the carers that he wished he was dead and wanted to end it all.

Referral upgraded to ‘priority’ by the coordinator and the patient was seen within 24 h.

The majority of referrals that are upgraded from routine to priority by the referral coordinator are for patients who are potentially expressing suicidal ideation. Any information collated by the coordinator suggesting feelings of hopelessness about the future, significant helplessness or worthlessness are regarded as possible precursors of suicidal despair (NHS Health Advisory Service, 1994). There is evidence to suggest that a majority of patients who take their own lives have informed someone of their intentions or have started to talk about suicide in a ‘less direct’ manner (Reference RullRull, 2007). Consequently, in Bridgend, a preliminary risk assessment that identifies morbid or suicidal ideas leads to the allocation of a priority response. This acknowledges the finding that worldwide older people are more at risk of completed suicide than any other age group (Reference O'Connell, Chin and CunninghamO'Connell et al, 2004) and meets the recommendation of the National Confidential Inquiry report on avoidable deaths that there should be greater emphasis on risk management in older people's services (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 2006: p. 9).

The impact of change and redesign

Outcomes

An excellent measure of the effectiveness of the referral coordination model is the number of times the priority setting differs from that suggested by the referrer. For example, requests for a routine review of suicidal ideas or overt violence would be upgraded to priority, whereas a request for an urgent placement capacity assessment would typically be downgraded to routine and allocated to a senior, often medical, staff member. This is a further example of compatibility with the aims of New Ways of Working (Department of Health, 2005).

A record of the frequency of these adjustments (plus referrals diverted because they are not appropriate for old age mental health services at all) is a valuable quantifiable outcome measure. Similarly, a record of when allocation decisions differ (such as allocation to a psychiatrist rather rather than a mental health nurse or social worker) is also quantifiable. An early audit of the Bridgend system suggested that in as many as one in eight referrals, the mental health response suggested (or requested) by the referrer was changed by the referral coordinator. Further audit is currently underway to substantiate these earlier findings by looking at patterns and trends over a longer period.

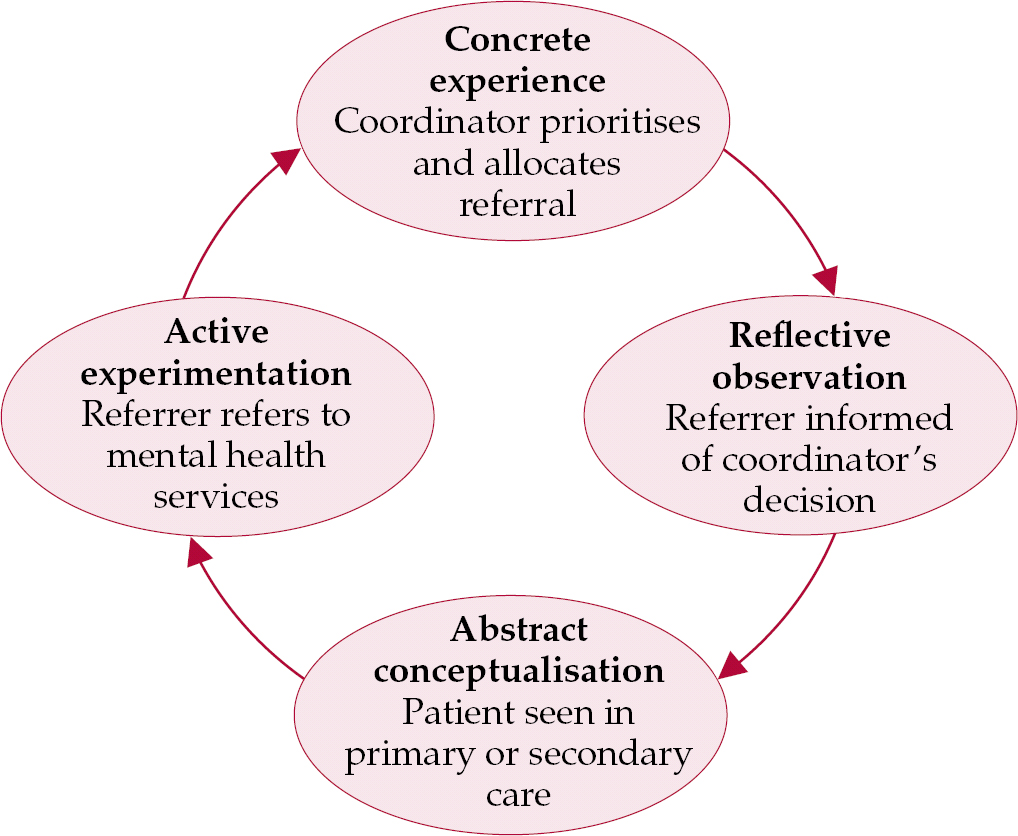

A further important benefit of the system is its qualitative advisory and educational aspect, which is considerably harder to record. Prompt feedback to referrers is made possible by the referral algorithm and the coordinator's input, and it is hoped that over time this will have an accumulative, passive, ‘drip-feed’ educational effect, similar to Reference KolbKolb's (1984) cycle of experiential learning (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 The experiential learning cycle of the clinical referral coordinator model (after Reference KolbKolb, 1984).

Statistics

All referral details, including prioritisation, allocation and reason for contact, are collated on a database to produce sound, high-quality data. This in turn allows the production of average or ‘typical’ referral profiles, firm baseline statistics from which to meaningfully measure change following training sessions or other educational interventions.

The Bridgend service receives on average 60–80 referrals a month; about 55–60% of referrals are from primary care and the remaining 40–45% from secondary care (some of these patients may already be known to mental health services). The relatively higher percentage of liaison referrals into old age psychiatry in Bridgend (Reference Lambourne, Ashaye and LambourneLambourne et al, 2006) is probably attributable to the Welsh model of integrated general medical and mental health NHS trusts; in addition, mental health services have been based in the large district general hospital since February 1994. These local circumstances make it easier to monitor the ability of current provision to meet current service demand for referrals (based on the local catchment area population of around 26 000 people over 65 years of age served by two full-time consultants in old age psychiatry).

Breakdown of referral patterns can highlight training needs and identify where referral numbers are low or inappropriate, as recommended by national guidelines (Audit Commission, 2002). It is also possible to predict an average referral rate from primary care (local figures suggest an annual referral rate of 3–3.5% of the population over 65) and to calculate a typical ‘priority’, ‘urgent’, ‘routine’ split. Consequently, individual educational needs can be targeted for particular surgeries, nursing homes or secondary care teams.

The database also enables further statistical comparison on whether some primary care practitioners tend to refer mental health problems initially to medical services rather than to psychiatry. Subsequent liaison referrals (in effect, referred indirectly – what we call ‘second-hand’ referrals) can be tracked back to the patient's registered primary care team and the referral rates contrasted with patients referred directly to mental health from the community.

Potential pitfalls

Acceptability

The redesign of the referral system, as with many innovations in practice, challenges traditional ways of working and introduces new responsibilities that may conflict with established professional roles.

In our experience at Bridgend, it became apparent over a period of time that some new staff (who had not been involved in the development of the referral algorithm) experienced difficulties accepting the system. Consequently the referral pathway and the role of the coordinator have had to be robust enough to overcome this (and other) barriers to change. Over time the novelty of a nurse and an algorithm directing the consultant psychiatrist has been largely accepted and introduction to the local referral model has been incorporated into an induction programme for new staff.

Similarly, the algorithm was conceptualised to ensure an extremely proactive response in crisis intervention. Thus, if nine out of ten ‘24-hour referrals’ prove to be false alarms this is validated by the one case out of ten that is captured safely and appropriately. However, not all new clinical colleagues appreciate this attitude to risk, perceiving their time to have been wasted; perhaps this is not surprising considering the uncompromising targets of seeing the patient within 24 h or 2 working days. None the less, local experience has demonstrated that these targets are sustainable and (arguably) worthwhile in light of the well-documented high risk of completed suicide by older people. In their study of help-seeking prior to suicide, Reference Owens, Lambert and DonovanOwens et al(2005) found that some relatives cited the slowness of the referral process as a contributory factor towards their relatives’ suicide and the authors recommend seeing a patient at risk ‘swiftly’.

Fit for purpose

The referral coordinator needs to be a knowledgeable and mature mental health clinician, ideally with experience of working in both community and hospital care, and able to deal with the pressures and possible conflict from both sides, i.e. referrer's demands and busy colleagues. Even though the referral algorithm provides a safe decision support system, triaging referrals draws on valuable clinical experience and intuition (using expertise as a practitioner (Reference BennerBenner, 1984)). Studies of telephone triage, particularly within NHS Direct, support the benefit of experience and confidence for safe and appropriate decision-making (Reference Morrell, Munro and O'CathainMorrell et al, 2002; Reference Monaghan, Clifford and McDonaldMonaghan et al, 2003).

The implementation, ongoing development and promotion of the service has allowed a rapid and continuous learning curve, with acquisition of advanced skills and knowledge, with the coordinator working at a highly autonomous level. It has to be recognised that the post could be an isolated role without regular feedback on referrals and patient outcomes. Strong mentorship and clinical supervision are both crucial to such an individual post, as well as easy access to senior medical advice (particularly in the early days of implementation). Initially in our case, the coordinator and secretary were not based within the main psychiatric department, which we would not recommend. It is advisable to give the coordinator short, regular clinical placements, for development and update and to counteract the potential loss of ‘hands-on’ skills and career restriction. Four years on, the job satisfaction derived from matching patient and carer needs by directing timely and appropriate resources remains high.

Robust arrangements for sickness and absence cover are essential, as the referral algorithm and investigative process rapidly become fundamental to effective daily clinical practice (arguably even deskilling psychiatrists in dealing with referrals). One sole coordinator is insufficient, yet continuity is needed, but a large team of coordinators would reduce the consistency of priority allocation. Initially, cover in Bridgend was provided by community mental health nurses and medical colleagues (this also served as an educational exercise); the long-term solution has been to incorporate the responsibility of deputising for the coordinator into a new nursing post which also supports education in primary care.

Lessons learned

It has proved helpful to verbally inform senior medical or nursing staff about referrals that will receive a 24-hour priority as soon as the allocation becomes clear. Similarly, if the coordinator becomes aware that a number of 24-hour and 2 working day referrals have been allocated in a short space of time, prompt discussion allows for informed delegation.

The practical value (especially in terms of clinical governance) of the consistent approach and response advocated by the clinician-led referral coordination model at Bridgend was evident when several locum psychiatrists were employed in the service over a 3-year period. The necessary compliance with the system, with its emphasis on receipting (a prompt letter of acknowledgement of the referral is sent to the referrer informing them of coordinator's decision) and tracking of the whole referral process, minimises the risk of a referral slipping through the net. A summary sheet of referrals, identifying priority and allocation awarded by the coordinator, can also provide an instant update for permanent staff and referral enquiries.

Subsequent experience of complaints management has indicated that the retention of the rough notes taken during the processing of referrals by the coordinator is extremely helpful in establishing how clinical decisions were taken. Although complaints are rare, the notes taken by the coordinator at time of referral have been used on two occasions to answer complaints and on one occasion to support a critical incident review.

As with any referral system, the Bridgend model is solely reliant on good information: the coordinator has no direct contact with the patient (the referral form includes a disclaimer to this effect). However, contrary to original misgivings, instances of referrers overemphasising risk to get their patients seen sooner are extremely rare. Indeed, we have found the opposite to be more likely (Box 2).

Box 2 Examples of referrals received marked by referrer as ‘routine’

-

• Actual or threatened use of weapons

-

• Self-harm

-

• Suicidal ideation

-

• Aggression requiring one-to-one nursing

-

• Wandering

-

• Lithium toxicity

-

• Water intoxication

Conclusions

The introduction of the referral system has fundamentally changed working practices in the Bridgend mental health service for older adults and should be of interest to organisations involved in monitoring quality, effectiveness and improvements in health-care. Our current algorithm is specific to old age psychiatry but the model itself is not and it could therefore be implemented much more widely, bearing in mind the observations and recommendations listed in Box 3. The cardinal features remain: the response to each referral is patient-centred and led by need; priorities and allocations are identified by a specialist clinician; and preliminary risk assessments are consistently conducted promptly on entry to the service. The process supports an equitable response to each referral and facilitates collation of information from different agencies (with partnership working as standard practice).

Box 3 Observations and recommendations

-

• Commitment of senior health and social services personnel is necessary

-

• Adequate designated cover arrangements to allow a continuous on-site office presence should be ensured

-

• Implementation of a pilot period and gradual roll out is essential to allow sufficient time for unforeseen problems to be identified and resolved

-

• There should be rigorous induction for new staff, with an opportunity for junior doctors to deputise as an educational experience

The attention paid to administrative aspects allows each referral to be acknowledged (and the referrer updated), reproduced electronically (for different staff team members or if the original is lost in the morass of office paperwork) and to be clearly typed and legible. Statistical analysis of referral data is starting to inform local management about the workload within the service and about non-attendance at out-patient clinics. Data are available to appraise local referrers in primary and secondary care about their own referral patterns and potential educational and local service needs.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the referral system described here promotes objective decision-making which is seen to be transparent – in terms of governance and quality, this makes it considerably easier for hard-pressed mental health staff to do and to be seen to be doing the ‘right thing’ (Reference Ben-TovimBen-Tovim, 2007).

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 The term ‘wicked problem’ usually describes:

-

a problems that are bad or ‘evil’

-

b problems that require ingenuity and creativity in management

-

c offenders using the criminal justice system

-

d problems where an imperfect solution will not be acceptable

-

e situations where a perfect solution can be easily identified.

-

-

2 A solely administrative referral management centre:

-

a should make an attempt to prioritise referrals clinically

-

b will not invariably improve routine patient data collection

-

c is appropriate for managing emergency referrals

-

d will not improve patient outcomes

-

e may provide valuable statistical information for purchasers and providers.

-

-

3 The main purpose of the investigative role of the coordinator is to:

-

a provide the general practitioner with more information

-

b ignore existing multiagency involvement

-

c collate evidence to produce a preliminary risk assessment

-

d ensure appropriate placement for the patient

-

e meet Welsh Assembly (or Westminster) targets.

-

-

4 Implementation of an effective referral coordinator system requires:

-

a no pilot period

-

b senior health and social services commitment

-

c ad hocdeputising arrangements

-

d no induction period for new staff

-

e off-site referral coordination.

-

-

5 Under the clinician-led model, if relatives raise issues that conflict with a referring GP's opinion that there is no risk involved, the referral coordinator should:

-

a rely on the information by the GP

-

b not seek senior advice

-

c dismiss the relatives concerns because they have no professional expertise on mental health problems

-

d rely on the referral pathway model's investigative process and algorithm

-

e post the referral back to the original GP with a request for more information.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | F |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.