Introduction

The lack of effective management of chronic low back pain (LBP) despite its significant burden in rural Nigeria [(70–85% one-year prevalence rate (Birabi et al., Reference Birabi, Dienye and Ndukwu2012)] increases disability and reinforces rural–urban disparity (Abdulraheem, Reference Abdulraheem2007; Igwesi-Chidobe, Reference Igwesi-Chidobe2012). Chronic LBP increases the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (Hoy et al., Reference Hoy, Brooks, Blyth and Buchbinder2010). This could be linked to associations between disability and exercise incapacity (Dean and Söderlund, Reference Dean and Söderlund2015); pain and increased psychosocial stress (Truchon, Reference Truchon2001); long-term use of opioids for chronic pain management and increased cardiovascular risk (Carragee, Reference Carragee2005). This is particularly relevant because people with chronic LBP habitually depend on opioids, which can be obtained over the counter without a doctor’s prescription in rural Nigeria (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b).

Psychosocial factors, such as fear avoidance beliefs, and occupational biomechanical factors, particularly heavy lifting and prolonged trunk bending, are associated with work-related disability, and increased LBP symptoms (Steenstra et al., Reference Steenstra, Verbeek, Heymans and Bongers2005; McNee et al., Reference Mcnee, Shambrook, Harris, Kim, Sampson, Palmer and Coggon2011), as found in rural Nigeria (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b). Psychosocial factors including illness perceptions and fear avoidance beliefs, but not biomechanical factors are the predictors of functional disability in patients with chronic LBP in rural Nigeria (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Coker, Onwasigwe, Sorinola and Godfrey2017a). In contrast, biomechanical factors are primarily targeted with no acknowledgement of psychosocial factors in the management of chronic LBP in rural Nigeria (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2015).

Limited access to conventional healthcare in rural Nigeria implies that self-management may be particularly useful because of its cost effectiveness and ease of access through community-based programmes. Self-management is ‘an individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition’ (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Wright, Sheasby, Turner and Hainsworth2002). Evidence-based treatment guidelines for chronic LBP recommend providing advice and education to promote self-management, combined with physical and psychosocial management which includes exercise and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for people with substantial disability (NICE, Reference Care2009).

Low literacy and motivation pose barriers to participation in CBT programmes (Ehde et al., Reference Ehde, Dillworth and Turner2014). However, integrating motivational interviewing with CBT may improve participation in populations with low motivation and literacy (Barrowclough et al., Reference Barrowclough, Haddock, Wykes, Beardmore, Conrod, Craig, Davies, Dunn, Eisner and Lewis2010; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Barrowclough, Allott, Day, Earnshaw and Wilson2011) such as rural Nigeria. Postural training may be an additional requirement for people in rural Nigeria as they are mostly involved in manual work, possibly implicating occupational biomechanical factors. Evidence suggests that integrated interventions targeting posture, exercises and psychosocial factors improve return to work outcomes (Heymans et al., Reference Heymans, VAN Tulder, Esmail, Bombardier and Koes2005). This study is aimed at assessing the feasibility and acceptability of a novel evidence-based theory-informed self-management programme – The ‘Good Back’ programme; and will primarily inform future larger scale process and outcome evaluations. This paper is reported according to the extended guidelines for pilot and feasibility studies (Thabane et al., Reference Thabane, Hopewell, Lancaster, Bond, Coleman, Campbell and Eldridge2016; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Lancaster, Campbell, Thabane, Hopewell, Coleman and Bond2016).

Methods

Study design

This study is an exploratory pragmatic non-randomised controlled feasibility study incorporating qualitative individual exit feedback interviews.

Study setting/context

Primary health care is often the only conventional health care accessible to rural Nigerian dwellers. Therefore, this study took place in a rural primary care centre serving about 15 000 typical rural Nigerian dwellers in Enugu state of south-eastern Nigeria. Pharmacological interventions are predominant in Nigerian primary care centres and typically include immunisations, and management of acute infections such as malaria, typhoid, diarrhoea and common cold. Chronic non-communicable diseases, responsible for over 50% of the total adult disease burden and morbidity/mortality in rural Nigeria (Abegunde et al., Reference Abegunde, Mathers, Adam, Ortegon and Strong2007), are minimally targeted in primary care.

Participant recruitment

Two village-wide announcements invited potential participants to the primary care centre where they were given information sheets and a detailed oral explanation of the study. They were given two days to decide on participation. Eligibility was ascertained via screening. Informed consent was subsequently obtained.

Screening

Body charts were used to identify pain in the lower back. Screening questions were interviewer-administered to rule out the ‘red flags’ for LBP by excluding chronic LBP associated with underlying serious pathology, radiculopathy or spinal stenosis (Downie et al., Reference Downie, Williams, Henschke, Hancock, Ostelo, DE Vet, Macaskill, Irwig, Van Tulder and Koes2013). Participants were aged 18 years and above, with pain lasting for more than 12 weeks.

Intervention

The ‘Good Back’ programme is an evidence-based theory-informed community-based self-management programme for people with chronic LBP in rural Nigeria. The programme targeted maladaptive illness perceptions and behaviours, and fear avoidance beliefs – the most important predictors of self-reported and performance-based disability in rural Nigeria (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Coker, Onwasigwe, Sorinola and Godfrey2017a; Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b). The programme is theoretically underpinned by the self-regulatory model of illness cognitions (Leventhal et al., Reference Leventhal, Leventhal and Contrada1998). CBT techniques were used to challenge maladaptive back pain beliefs, emotions and behaviours – particularly drug dependence and cure seeking (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b). Any exercise improves pain-related functional disability, and postural hygiene may improve pain-related work disability (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Baxter and Gracey2004; Van Middelkoop et al., Reference Van Middelkoop, Rubinstein, Kuijpers, Verhagen, Ostelo, Koes and Van Tulder2011). Motivational interviewing techniques were used to communicate health information, and facilitate exercise and posture-related behaviour change, in line with the systematic review findings (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kengne, Sorinola and Godfrey2018). Exercises included aerobic, strengthening, neuromuscular, flexibility and relaxation exercises. Postural hygiene was demonstrated with culturally relevant functional activities, including farming, carpentry, lifting heavy objects, fetching water, sweeping etc. Illustration-only patient booklets were used to promote educational aspects of the programme in this population with about 40% illiteracy rate (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Obiekwe, Sorinola and Godfrey2017c; Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b).

The programme is a six-week self-management programme delivered once weekly. The programme was mainly group-based. Inclusion of individual discussion sessions depended on participants’ demands for more intimate topics, particularly the impact of chronic LBP on sexuality. The six discussion themes were: challenging a biomechanical model of chronic LBP; challenging an infective-degenerative understanding of chronic LBP; challenging other negative thoughts about back pain; managing exercise, pacing, goal setting and relaxation; chronic disease and chronic pain; and managing/coping with flare ups, relaxation, help seeking and self-management. These themes were informed by previous qualitative studies in this population (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2015; Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b) and back pain rehabilitation programmes. Each weekly session was based on a different theme.

Each programme session has six phases, including education about back pain and health care; mapping of existing illness perceptions; challenging maladaptive illness perceptions; formulation of alternative illness perceptions and associated behaviours; practising more adaptive behaviour, like exercise and postural hygiene, in a supervised session, and exploring the incorporation of these into daily lives; and testing and strengthening any alternative illness perceptions by confirming their utility in daily life.

Assignment to study arms

Random allocation was not done in this exploratory study. Although this limited internal validity, convenient assignment ensured that (1) the few interested younger adults, male participants and non-farmers were purposively assigned equally into the study arms; (2) non-participation was reduced since this was the first non-pharmacological behaviour change intervention in this population with an entrenched pharmacological treatment model (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b). Moreover, this study was not aimed at establishing causal relationships.

Outcome assessment

Pre- and post-test outcome assessments were done by a trained physiotherapist unaware of group assignment.

Primary outcomes

Feasibility was assessed in terms of recruitment rate, intervention delivery, proportion of planned treatment attended, retention/dropout rate, adherence to recommended self-management strategies and the primary outcome of disability measured with the Igbo Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Obiekwe, Sorinola and Godfrey2017c). A total score of 24 signifies the highest possible disability and 0 means no disability. Adherence to recommended exercises was assessed with the Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS) (Newman-Beinart et al., Reference Newman-Beinart, Norton, Dowling, Gavriloff, Vari, Weinman and Godfrey2017). A maximum score of 24 signifies perfect adherence and lower values reflect poorer adherence.

Acceptability of the programme was ascertained for all participants in the self-management group, using structured qualitative exit feedback interviews. An open-ended Igbo interview guide explored participants’ experiences of the programme, adherence behaviour and suggestions for programme improvement. Interviews were recorded verbatim as text.

Secondary outcomes

These were performance-based disability [(Back Performance Scale; Strand et al., Reference Strand, Moe-Nilssen and Ljunggren2002)], illness perceptions [(Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire – BIPQ (Broadbent et al., Reference Broadbent, Petrie, Main and Weinman2006)], fear avoidance beliefs [(Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire – FABQ (Waddell et al., Reference Waddell, Newton, Henderson, Somerville and Main1993)], pain intensity [(11-point box scale – 11-BS (Hawker et al., Reference Hawker, Mian, Kendzerska and French2011)], pain medication use, systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Pain medication use was measured by determining the number of pain tablets ingested in the past two weeks due to back pain. Blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer as an exercise precaution.

All measures except performance-based disability and blood pressure were self-reported, and hence were interviewer-administered using cross-culturally adapted measures (Beaton et al., Reference Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin and Ferraz2000).

Timing of outcome assessment

Recruitment rate, reflection on intervention delivery, proportion of planned treatment attended and retention/dropout rate were assessed while the programme was ongoing. All primary and secondary outcomes except exercise adherence were administered at baseline and immediately after the programme. Exercise adherence for a past week was assessed at the beginning of each programme session.

Sample size

Ten was an adequate size for one self-management group, in line with the Stanford self-management support approach and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline recommendations (NICE, Reference Care2009; Lawn and Schoo, Reference Lawn and Schoo2010). This study was not designed to confirm efficacy or effectiveness.

A priori feasibility criteria

An acceptable effect size was set at 0.2 in self-reported disability – RMDQ, in line with the self-management literature (Warsi et al., Reference Warsi, Lavalley, Wang, Avorn and Solomon2003; Du et al., Reference Du, Yuan, Xiao, Chu, Qiu and Qian2011). Based on feasibility criteria for CBT interventions (Pincus et al., Reference Pincus, Anwar, Mccracken, Mcgregor, Graham, Collinson and Farrin2013; Pincus et al., Reference Pincus, Anwar, Mccracken, Mcgregor, Graham, Collinson, Mcbeth, Watson, Morley and Henderson2015), this study aimed at achieving at least 50% recruitment rate, 60% programme completion, and 85% programme attendance for one session. Loss of data was set at not exceeding 35% (10% due to non-compliance and 25% loss to follow-up).

Intervention delivery

The lead author, a physiotherapist with 15 years of clinical experience in primary care and community-based rehabilitation, with some training in CBT and motivational interviewing, delivered the intervention. Each programme session lasted approximately 2 h with additional 30 min of break periods.

Data analyses

Quantitative data analyses were mainly descriptive. Proportions/percentages, means and standard deviations of pre- and post-test outcomes (within-group data) and change scores (between-group data) were calculated using SPSS version 22. Effect sizes (between-group) were calculated with Hedges’ g and Glass’s Δ (Lakens, Reference Lakens2013).

Qualitative inductive content analysis reflecting a quantitative analysis of meaning (number of people reporting a theme) was performed with NVivo version 10. Interview transcripts were translated to English using evidence-based guidelines (Chen and Boore, Reference Chen and Boore2010). Analysis using a manifest rather than interpreted content of interview transcripts was done due to the structured interview format that directly answered specific questions for programme improvement.

Results

Participants

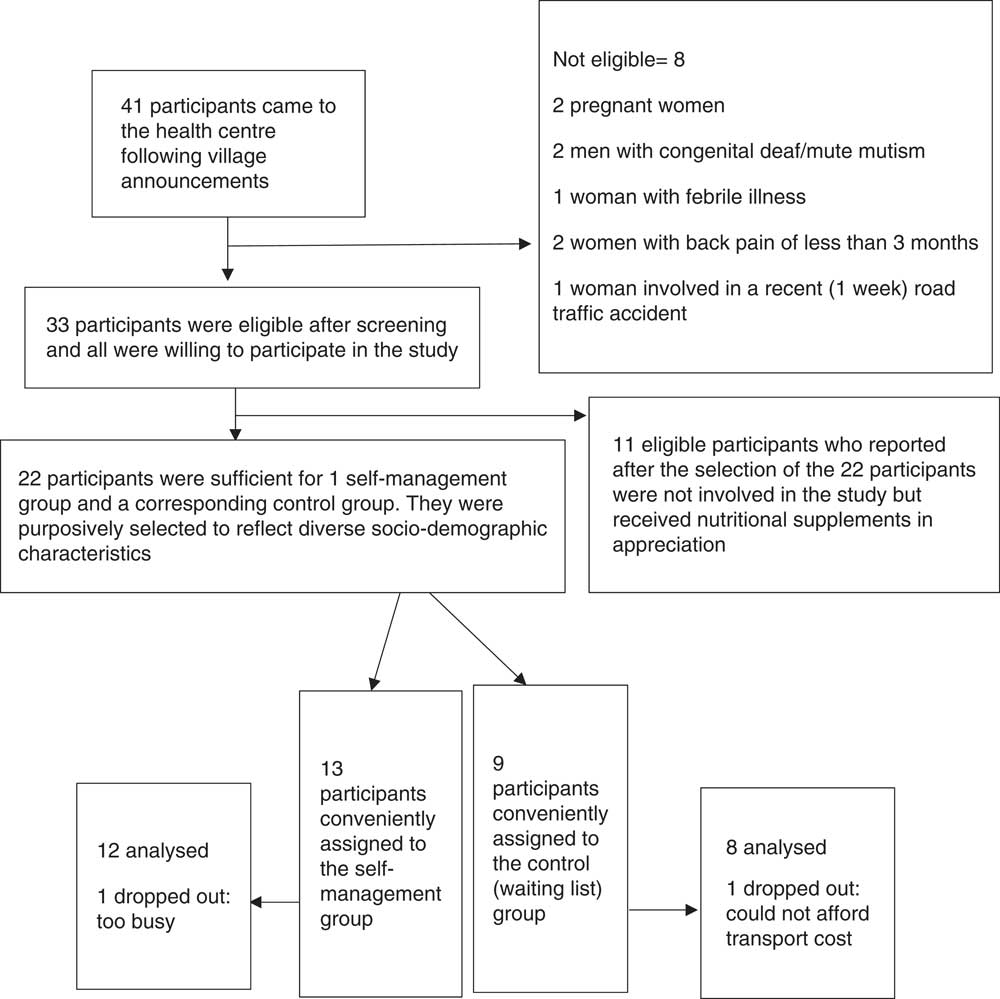

Figure 1 details participant selection process. A total of 13 participants willing to come for the weekly sessions at the primary care centre were conveniently assigned to the Good Back programme. Nine participants that only wanted to come once were assigned to the control group.

Figure 1 Recruitment process

Baseline data

Table 1 shows that self-reported disability (RMDQ), fear avoidance beliefs (FABQ), systolic and diastolic blood pressure were balanced in the two groups.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical baseline characteristics by study arm

SD: standard deviation

Intervention fidelity

A multi-disciplinary research team appraised the video recordings of all six sessions to confirm intervention fidelity.

Proportion of planned treatment attended

Programme attendance rate was 83%. The proportion of participants with 100% attendance was 77%. Of the three males in the self-management group, one attended only half (before phase five) of one session out of the six sessions. Another male participant came late for two sessions (after phase four and during phase one). The third male left after phase four in one session was late during phase four in one session, and came late during phase one of another session.

Retention/dropout rate

Retention rate for the self-management programme was 92%. Dropout rate (loss to follow-up) was 8% in the self-management group and 11% in the usual care/waiting list group (Figure 1).

Adherence to recommended self-management strategies

Exercise adherence (EARS) increased with the first few sessions of the programme, reduced to the starting values in the mid sessions and then increased beyond the starting values with subsequent sessions: 15.9 (5.2); 17.9 (4.5); 18.4 (4.9); 16.6 (6.0); 20.6 (3.7) and 20.5 (2.9).

Outcomes and estimation

Table 2 shows that there were better improvements in all outcomes in the self-management group. Table 3 depicts mean baseline and change scores split by gender which showed that gender-related programme attendance influenced outcomes.

Table 2 Means and effect sizes in the self-management and usual care/waiting list groups

SBP= systolic blood pressure; DBP= diastolic blood pressure

Table 3 Baseline outcome scores and mean changes by gender in the self-management group

SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure

Participants’ experiences of the Good Back programme

More detailed explanation of themes, subthemes and narrative with participant’s quotes are given in Supplementary material.

Discussion

This is the first study exploring a novel evidence-based theory-informed biopsychosocial intervention for chronic LBP management in a rural African context. Overall, a good recruitment rate and intervention fidelity were observed. Good treatment uptake, retention and adherence to recommended self-management strategies, good acceptability and promising clinical outcomes were observed. These results provide a rationale for more rigorous intervention testing and potential implementation.

The recruitment rate was 100% (all the eligible participants wanted to participate). This is higher than 55–90% reported in the UK and USA (Morone et al., Reference Morone, Greco and Weiner2008; Bearne et al., Reference Bearne, Walsh, Jessep and Hurley2011; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mcdonough, Bradbury, Liddle, Walsh, Dhamija, Glasgow, Gormley, Mccann and Park2012). Limited access to effective musculoskeletal health care in rural Nigeria may have increased motivation to participate in this study. Although the overall recruitment rate was good, it is noteworthy that male participants were difficult to recruit which requires further investigation.

Convenient assignment rather than random assignment to the study arms could have reduced attrition rates by ensuring that the most motivated people participated in the self-management programme. The limitation is that it could have resulted in pre-existing differences that may in part explain the greater improvements in the self-management group. However, improvements in self-reported disability, fear avoidance beliefs and blood pressure which were balanced in the two groups is promising.

The acceptability of the programme was good, as all the participants preferred the programme over usual care. This is not surprising since the intervention was delivered at no cost with promising outcomes, whereas pain medication, the usual care for chronic LBP in rural Nigeria only has transient pain relief despite significant costs (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b).

The overall attendance at the programme was 83%, comparable with the 83.8% and 81% attendance at a mindfulness-based meditation programme for community dwelling older adults with chronic LBP in the USA (Morone et al., Reference Morone, Greco and Weiner2008), and exercise-based rehabilitation programme for chronic hip pain in the UK (Bearne et al., Reference Bearne, Walsh, Jessep and Hurley2011). However, male participants had erratic attendance, which they associated with work. Delivering the intervention in work sites could be explored in future studies. Male participants might have also been uncomfortable attending a programme with a majority of women. An equal gender representation, or a group run specifically for men could be explored in future studies.

Exercise adherence was good possibly due to the use of a relevant theory, integrating CBT and motivational interviewing techniques, and assessing adherence between sessions and immediately after the programme. This is despite the community’s view of exercises as illegitimate treatment for chronic LBP which may inhibit long-term exercise behaviour change. Longer follow-up periods plus addressing negative community beliefs may be necessary in future studies in rural Nigeria.

Improvements in participants’ symptoms may have been the strongest determinant of both programme attendance and exercise adherence. This implies that future trials in this context must deliver interventions at a dose and duration sufficient to improve participants’ symptoms before follow-up. It is therefore unlikely that brief educational interventions without exercise demonstrations will be effective in rural Nigeria. Additionally, combined group and individual discussion sessions informed by CBT and motivational interviewing may have further increased autonomous motivation through a collaborative patient-centred communication style.

Reductions in self-reported disability, illness perceptions, fear avoidance beliefs, pain intensity and pain medication use concurs with the Leventhal’s self-regulatory model of illness cognitions (Leventhal et al., Reference Leventhal, Leventhal and Contrada1998). Thus, modification of back pain beliefs may have modified coping strategies and emotions and so influenced disability. However, effect sizes may have been moderated by unequal baseline scores for many outcomes.

Female participants had better outcomes with more precise estimates, except for pain medication use, for which they had a lower baseline value. This might be because male participants missed most of the group discussion sessions where psychosocial factors were specifically targeted. However, male participants’ lower baseline scores in the psychosocial factors and the very small sample size in this study may have tempered this finding, and hence needs further investigation in future studies.

Reduction in pain medication use, most of which were opioids such as tramadol, may be of public health importance. The long-term use of opioids increases cardiovascular risk and has limited use in chronic LBP (Carragee, Reference Carragee2005). Opioid medication dependence is a salient maladaptive coping strategy in this population with high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes comorbidity (Igwesi-Chidobe et al., Reference Igwesi-Chidobe, Kitchen, Sorinola and Godfrey2017b).

Unexpected improvements in blood pressure, especially in the females, might be because targeting psychosocial factors and exercising may have modified pain experience and reduced stress (Truchon, Reference Truchon2001). Evidence suggests that psychosocial stress, increased by pain (Truchon, Reference Truchon2001), contributes to cardiovascular disease, and that stress reduction reduces blood pressure (Rainforth et al., Reference Rainforth, Schneider, Nidich, Gaylord-King, Salerno and Anderson2007). However, the very small number of male participants means that this finding needs to be interpreted with caution. Blood pressure improvements may have also occurred through participants’ better adherence to antihypertensive drugs which may have been facilitated by the discussion sessions that contrasted medication use for self-management of chronic LBP from that for hypertension.

The Good Back programme seemed feasible and acceptable with promising clinical outcomes. It should be rigorously tested after incorporating the requested programme modifications. Exploration of necessary training and supervision needs of first line primary health care workers in rural Nigeria would be essential for refining this programme for a future randomised clinical trial and for possible implementation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000070

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Tertiary Education Trust Fund, Nigeria and the Schlumberger Foundation faculty for the future fellowship grant, the Netherlands. Both organisations had no influence on the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation (King’s College London – Ref: BDM/13/14-99; and University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital – Ref: UNTH/CSA/329/ Vol.5) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.