I. Introduction

When Leonard Woolley published the preliminary results of his excavation at Al-Mina (36° 4’ 49” N, 35° 59’ 13” E; see fig. 1) in the Journal of Hellenic Studies in 1938, he initiated a controversial debate about Greek settlements in the East, which is still ongoing. So far, several sites have been connected to a temporary or permanent Greek presence in the Levant, be it as a home away from home, an apoikia (‘colony’), or as part of a community residing in a city or a port of trade (enoikismos). These discussions largely neglected the possible existence of a Greek settlement in the Levant according to a letter (ND 2737; henceforth SAA 19 26 after the most recent edition) from the state correspondence of Tiglath-pileser III of Assyria (r. 744–727 BC) found at his capital city of Kalhu (modern Nimrud). Footnote 1 This paper discusses this document together with another letter from the same dossier (ND 2370; henceforth SAA 19 25) Footnote 2 and analyses the implications of these sources for the possibility of a permanent Greek presence in the northern Levant during the eighth century BC in light of the new edition of Mikko Luukko, Footnote 3 which has clarified certain details in the readings of the letters.

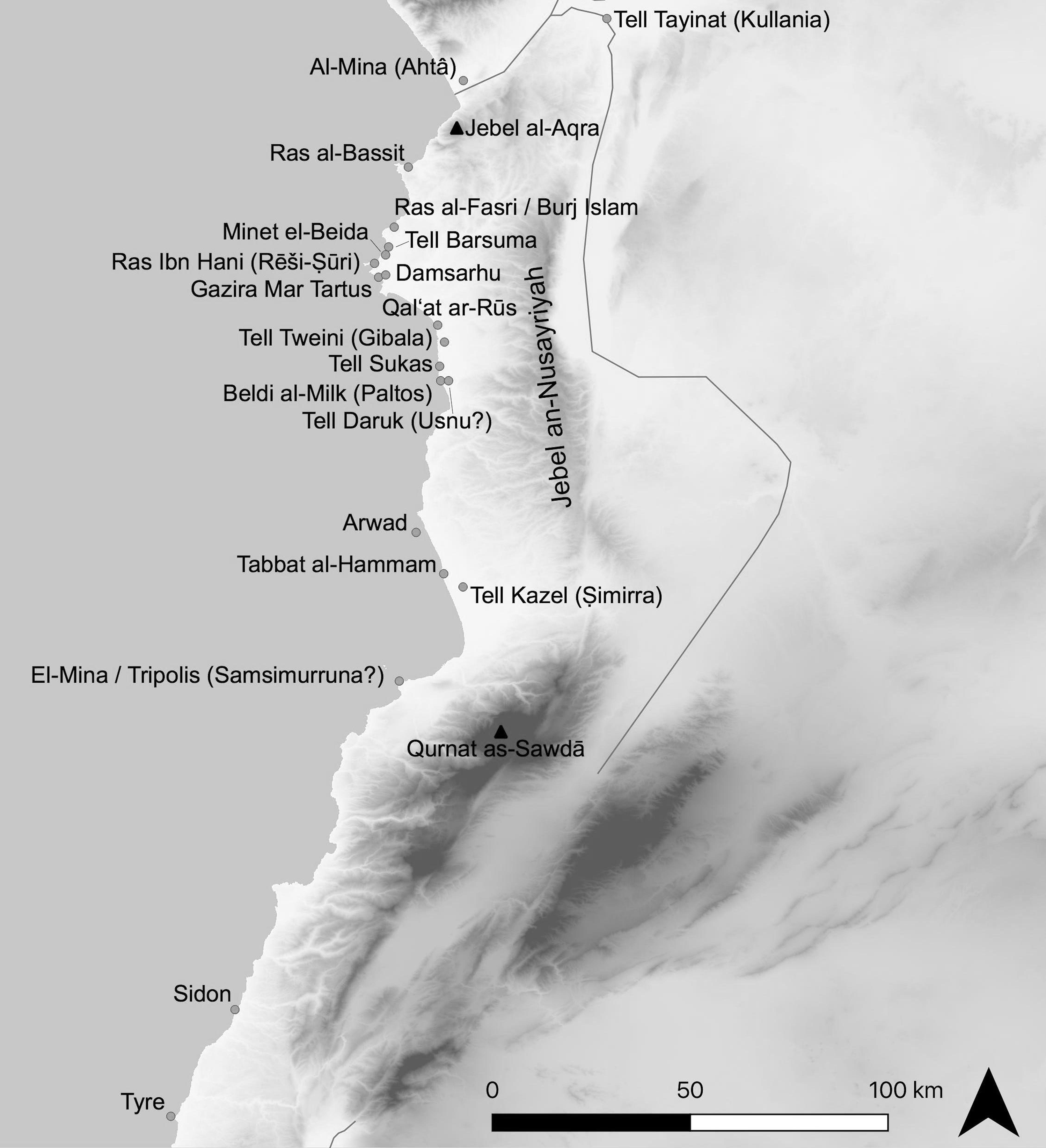

Fig. 1. Map indicating the sites on the Mediterranean coast discussed in this paper. Prepared by Andrea Squitieri (LMU Munich).

Both letters are attributed to Qurdi-Aššur-lamur, who served as the first governor of the Neo-Assyrian province of Ṣimirra, which was created in the coastal region of the conquered kingdom of Hamath in 738 BC. Footnote 4 A frequent correspondent with his king Tiglath-pileser III, he reported on the often challenging situation in and around the newly established province under his control, and this is also the case in these two letters, both only fragmentarily preserved.

SAA 19 25 deals with a raid carried out in Qurdi-Aššur-lamur’s territory by a group of people identified as KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a, in the first attestation of this term in the Neo-Assyrian sources. The second letter, SAA 19 26, reports on an Assyrian mission to press locals into imperial service, which results in the pursuit of the inhabitants of a place called URU.ia-ú-na. Past scholarship connected both, the Yauneans (KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a) and Yauna (URU.ia-ú-na), to various degrees with the ethnonym ‘Ionians’ and/or the toponym ‘Ionia’, with the precise etymology being contested. Although previous commentators placed URU.ia-ú-na (attested only here in the Neo-Assyrian sources) Footnote 5 in the northern Levant, its precise location is unclear. The relationship between Yauna and the Yauneans who plague the people settling on the Levantine coast is also obscure according to SAA 19 25 and later attestations from the late eighth century BC onwards.

In this paper, we reconsider the two letters to clarify the historical and cultural context of the people called KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a and the town of URU.ia-ú-na, and explore the relationship between these terms. Furthermore, we try to establish what can be safely said about the location of the town of Yauna and discuss the historical and cultural background of its foundation. We argue that the Assyrians encountered the Yauneans for the first time in this locality and that, to the Assyrians, the Yauneans therefore were originally the inhabitants of Yauna, and that due to the similarities perceived between the inhabitants of this place and the (other?) Greeks appearing in the Levant, the Assyrians came to apply this ethnonym universally to all these people, and no longer solely to the citizens of URU.ia-ú-na.

II. Greeks overseas: the letters’ significance for the transfer debate

Among scholars of ancient Greece, there is broad agreement that Near Eastern cultural traditions impacted on Greek art, literature and religion in the Late Geometric and Archaic periods. Footnote 6 More recently, the debate has focussed on identifying modes and scenarios of transmission, for which various theoretical approaches and models have been proposed. Footnote 7 Discussions have been especially controversial concerning the mode and locality of knowledge transfer, and the identity of the agents, with two primary scenarios being suggested: that the ideas and objects were transferred via easterners travelling to the Aegean, or that Greeks were directly confronted with new impulses in Greek outposts established in the East. Footnote 8

Due to the relatively large amount of Greek pottery found at Syrian harbour sites such as Al-Mina, Ras al-Bassit (35° 50’ 45” N, 35° 50’ 16” E), Tell Sukas (35° 18’ 22” N, 35° 55’ 22” E) and, to a lesser degree, Ras Ibn Hani (35° 35’ 6” N, 35° 44’ 46” E) and Tabbat al-Hammam (34° 44’ 38” N, 35° 56’ 2” E), Footnote 9 the northern Levant stands out as a potential contact zone for the Greeks’ hypothetical encounter with Near Eastern cultural practices and knowledge. But, such pottery on its own has been sensibly considered an insufficient indicator for a Greek presence, hence interpretations that assumed resident Greeks at these north Syrian ports have met with criticism. Footnote 10

Somewhat surprisingly, the settlement of Poseideion, as mentioned by Herodotus (3.91) is the only reference in a Greek text to point to the existence of Greek settlements in the east in the Early Iron Age, rarely features in these discussions. This is in part due to the lack of consensus on its location. Ras al-Bassit on the northern coast of Syria, 53km north of Latakia, was certainly known as Poseideion, as demonstrated by coins from the final quarter of the fourth century BC onwards. Footnote 11 However, Robin Lane Fox argued that Herodotus’ Poseideion should be located further north, towards Cilicia at an as yet unidentified place still awaiting discovery by archaeologists. Footnote 12

Identifying possible Greek settlements in the Levant is crucial for the ‘transfer debate’. It is therefore remarkable that the Assyrian letter SAA 19 26, with its mention of a settlement called Yauna (URU.ia-ú-na), has not received more attention in this context. A notable exception is Lane Fox, Footnote 13 although his interpretation as a reference to Al-Mina is untenable (see below, section V.i). While Robert Rollinger, who has repeatedly and at length discussed the attestations for ‘Ionians’ in the Assyrian sources, mentions this specific text in some of his works, Footnote 14 Iris von Bredow, in the most recent analysis of contact zones between Greeks and Near Easterners, ignored the letter entirely, as had most previous scholarship. Footnote 15 The present paper, therefore, presents a much-needed in-depth analysis of this letter and the near-contemporaneous letter SAA 19 25, with its mention of Yauneans (KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a), Footnote 16 from the same dossier of correspondence between the governor Qurdi-Aššur-lamur and his master, Tiglath-pileser III of Assyria.

III. The letters’ historical context

In the ninth century BC, the kingdom of Assyria established itself as the dominant political power in Syria. After a military campaign to the Levant in the ninth year of his reign, Footnote 17 Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) hosted among his guests of honour at the grand opening of his new capital city Kalhu delegates from the coastal regions of Pattin (also Unqu, centred on Tell Tayinat = Assyrian Kullania in the Amuq plain, which inherited its name from the ancient toponym Unqu), Tyre and Sidon, and from the polities controlling traffic along and across the Euphrates, Hatti (in this context, the kingdom of Carchemish), Gurgum (centred on Kahramanmaraş = Assyrian Marqasu) and Malidu (centred on Malatya = Assyrian Malidu) as well as, further south, Hindanu (region of Deir ez-Zor) and Suhu (region of Ana). Footnote 18 These visitors, therefore, had a front-row view of the event that marked the beginning of a new, imperial era in Assyria’s long history. During the reign of Ashurnasirpal’s son and successor Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BC), a pronounced focus on Assyrian interests in the coastal areas of northern Syria and Phoenicia is in evidence. Footnote 19

Although the empire insisted on its role as these regions’ hegemonic overlord, several Syrian kingdoms, in particular Damascus and Hamath, opposed the Assyrian claim. Moreover, the later reign of Shalmaneser saw the rise of the eastern Anatolian power Urartu on the empire’s northern and northeastern borders, with the ensuing conflicts focussing on the regions controlling the northern Euphrates crossings and the key passages across the Zagros Mountains into western Iran. While the empire did not forgo its claims over the coastal regions of the Levant, Footnote 20 clashes with Urartu and its growing number of allies as well as internal problems kept the empire’s regional involvement strictly limited. Footnote 21

This changed drastically with the ascent of Tiglath-pileser III to the Assyrian throne in 744 BC. A usurper, albeit of royal descent, he started an extremely successful programme of rapid territorial expansion that continued into the short reign of his son and designated heir Shalmaneser V (r. 726–722 BC), who had actively supported his father’s conquests as crown prince. The expansion slowed down markedly after the usurpation of Shalmaneser’s throne by his brother Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC), which led to widespread revolts that occupied the attention of Assyrian forces. The annexation of new territories as provinces came to a complete standstill after Sargon’s untimely death on the battlefield in Central Anatolia, when his son and designated heir Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) took the throne. By that time, however, the empire’s holdings included all regions west of the Euphrates, Footnote 22 with the notable exceptions of Tyre, Sidon and some other Phoenician city states including the island of Arwad.

For our purposes, the crucial year is 738 BC. That year, the kingdom of Pattin/Unqu, which was centred on the Amuq plain of the Orontes River, was turned into an Assyrian province called Kullania (named after the ancient name of its capital city, Tell Tayinat; Footnote 23 36° 14’ 54” N, 36° 22’ 34” E), and in that same year, the coastal stretches to Pattin’s south, formerly part of the kingdom of Hamath (centred on Hama), were established as the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra (named after its capital city, almost certainly Tell Kazel). Footnote 24

The site of Tell Kazel lies on the northern bank of the Nahr al-Abrash in the Akkar plain, about 24km south of Tartus and 40km north of Tripolis. Footnote 25 It occupies an important strategic location as from there a route followed the river through the formidable barrier formed by the Jebel an-Nusayriyah to the north and the Lebanon range to the south into the inland regions of Syria. Fittingly, the city was called ‘Ṣimirra at the foot of Mount Lebanon’ in the inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser. Footnote 26 Further north, the landmark that indicated the border between the two Assyrian administrative units (and previously the kingdoms of Pattin/Unqu and Hamath) on the Mediterranean coast was the Jebel al-Aqra, known as Mount Ṣapūnu in contemporary Assyrian, Aramaic and Phoenician sources. Footnote 27 Therefore, the extent of the coastline of Ṣimirra corresponds closely to that of modern Syria, bordering on Lebanon in the south and Hatay province of Turkey in the north.

By the end of the reign of Sargon II, Assyria had been transformed from a hegemonic empire into a territorial one, Footnote 28 and most of the Levantine polities (as well as the coastal region of Cilicia, known as Que) had been made Assyrian provinces while the remaining polities accepted their client status vis-à-vis the Assyrian king. The provincial administration was run by a group of centrally trained imperial officials headed by a governor who was personally appointed by the king. In the words of Esarhaddon of Assyria (680–669 BC), the provincial administration of Kullania consisted of:

the governor of Kullania (Kunalia), with the deputy (governor), the major-domo, the scribes, the chariot drivers, the ‘third men’ (of a chariot crew), the village managers, the information officers, the prefects, the cohort commanders, the charioteers, the cavalrymen, the exempt, the outriders, the specialists, the shi[eld bearers], the craftsmen, (and) with [all] the men [of his hands], great and small, as many as there a[re]. Footnote 29

Headed by the governor and his deputy, this group of men consisted of administrators (major-domo, scribes, village managers), military personnel (information officers, prefects, cohort commanders, charioteers, chariot drivers, ‘third men’, cavalrymen, outriders, shield-bearers, the exempt) as well as ‘specialists’ (LÚ.um-ma-a-ni: highly trained master scholars and artisans that could include, for example, goldsmiths) and ‘craftsmen’ (LÚ.kit-ki-tu-u). While the military clearly formed a large part of the Assyrian provincial administration, Footnote 30 the mention of specialists and craftsmen makes it clear that the personnel dispatched from the centre of the empire included people schooled in arts and literature.

Moreover, the empire also sought to ensure close control over its client states to protect itself from both external and internal threats. A key mechanism was the posting of an Assyrian official (Assyrian qēpu, meaning ‘trusted one’) at the client ruler’s court who looked after Assyria’s strategic interests. Footnote 31 On the Mediterranean coast, the control of the lucrative maritime trade and the connecting inland routes was of special importance, both to secure strategically vital raw materials such as timber and metals and to provide the refined court society, and its affluent imitators across the empire, with luxury goods. Footnote 32 In order to manage imports and exports, the Assyrian administration established trading posts (Assyrian bīt kāri, meaning ‘house of trade’) where the empire’s taxes and dues were collected. Footnote 33

These brief remarks on the historical and administrative developments affecting the coastal regions of northern Syria provide an introduction to our discussion of the letters SAA 19 25 and SAA 19 26. Found in 1952 together with administrative documents from the reign of Sargon II in a room of the Northwest Palace of the Assyrian capital city of Kalhu, the approximately 230 ‘Nimrud Letters’ are part of the state correspondence of Tiglath-pileser III and his second successor Sargon II. Footnote 34 The two letters under consideration are part of the dossier of Qurdi-Aššur-lamur, an imperial official under Tiglath-pileser III and the first governor of the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra. Footnote 35 SAA 19 25 mentions its sender as Qurdi-ili-lamur, likely a mistake or else an alternative form of the name Qurdi-Aššur-lamur. Footnote 36 However, the beginning of letter SAA 19 26, and hence the name of its sender, is broken off, and the (universally accepted) attribution to Qurdi-Aššur-lamur therefore relies on contextual arguments. Footnote 37

IV. SAA 19 25: the Yauneans (KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a) and the ᾿Iά(ϝ)ονϵς

Who are the Yauneans (KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a)? This question has intrigued scholars since the designation was first recognized in the earliest publications of Assyrian royal inscriptions, as an identification with the Ionians, or more broadly the Greeks, was the obvious inference, given the close resemblance of the term to Persian yauna and Hebrew ywn. Footnote 38 As noted above, our letter SAA 19 25 is the earliest reference in the Assyrian documentation.

After the briefest of greetings, the tersely formulated letter immediately comes to the point: ‘The Yauneans came and gave battle in Samsim[urruna], HariṢû and [GN1]’. Footnote 39 Of the two preserved place names, HariṢû is only attested in the present letter. Footnote 40 However, Samsimurruna is well known from other Assyrian sources, where this Phoenician city appears as an independent polity headed by a king at least until the early reign of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–631 BC). Footnote 41 By that time, the only other remaining Phoenician kingdoms were Tyre, Byblos and Arwad while the rest of the Phoenician lands, most prominently Sidon, had been integrated into the Assyrian provincial holdings. Because the cities of Tyre and Arwad (Arados; 34° 51’ 21” N, 35° 51’ 32” E) were situated on islands off the Levantine coast, these two states were arguably in a better position to resist territorial integration than their neighbours. The same may be true for Samsimurruna, whose exact location is not known but is generally assumed to lie in northern Lebanon. If we accept this line of argument, then the kingdom of Samsimurruna is likely to have been centred on El-Mina (34° 27’ 11” N, 35° 48’ 48” E), the harbour of Tripolis, with a cluster of nine small islands off its coast. While there is evidence for Iron Age occupation there, the archaeology of the area is poorly known because it is mostly covered by the medieval and modern architecture of Lebanon’s second largest city. Footnote 42 From the letter, it is also clear that the three sites targeted by the Yauneans must be located very close to each other. If one accepts the argument for placing Samsimurruna, and therefore also the other sites, in El-Mina and the islands around it, then one could argue that it was this cluster of three settlements that gave Tripolis its later Greek name, meaning ‘three cities’.

The letter continues with a brief report on how the governor learned about the incident and how he reacted: ‘A cav[al]ry[man] came to the king’s city; I [t]ook the exempt (that is, a specific type of troops in the Assyrian forces) and departed’. Footnote 43 A messenger on horseback swiftly alerted the governor, who took what troops were available (the exempt likely being reserve troops of veterans) and immediately set out to come to the rescue of the settlements under attack. The letter then describes the situation upon the Assyrian forces’ arrival: ‘They (that is, the Yauneans) did [n]ot take anyth[ing]; when [they sa]w [my] tr[oops they embarked] th[eir] boats and [fled] into the midst of the sea’. Footnote 44 From this it is clear that the Yauneans were seaborne raiders. The letter breaks off here, and the information on its reverse is not directly connected to these events. Footnote 45

In this source, we see the governor of Ṣimirra come to the aid of the Assyrian Empire’s Phoenician allies against a Yaunean raiding party that, once the Assyrian forces arrived on the scene, swiftly fled out to sea, whence these pirates presumably had first arrived. After this first attestation in the state correspondence of Tiglath-pileser III, the KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a (as they were called in the archival texts using the vernacular Neo-Assyrian variant of Akkadian) or KUR.ia-man-a-a/KUR.ia-am-na-a-a (so in the royal inscriptions written in the literary lect Standard Babylonian, a highly codified variant of Akkadian, or in the archival texts using the vernacular Neo-Babylonian variant of Akkadian) leave a steady footprint in the documentation of the Assyrian Empire. Footnote 46 The term’s connection to Greek ᾿Iά(ϝ)ονϵς, as used in the Archaic sources, has been generally accepted by both Classicists and Assyriologists. Footnote 47

It is worth emphasizing how limited the available Archaic Greek references for Iά(ϝ)ονϵς actually are. The term seemingly first appears in the Greek sources in Homer’s Iliad, Footnote 48 although it has been argued that the specific passage must be considered a later interpolation of the sixth century BC. Footnote 49 The term may also appear in a fragmentary poem of Sappho, writing sometime in the late seventh or early sixth century BC. Footnote 50 A reference in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo dates to roughly the same time, Footnote 51 where Ἰάονϵς ἑλκϵχίτωνϵς, ‘Ionians with trailing chitons’, celebrate festivals in honour of Apollo on the island of Delos. As the cult songs performed by the Delian girls are said to be in various dialects or languages, Footnote 52 several scholars have suggested that the Ionians attending the Delos festival came from various regions of the Aegean and that the celebrants included non-Greek speakers. Footnote 53 Finally, a passage in Solon refers to Attica as the oldest Ionian land (γαῖαν [Ἰ]αονίης), which is generally considered a reflection of Athenian attempts to gain precedence among the celebrants at the Delos festival already in the early sixth century BC. Footnote 54 Therefore, if one disregards the contested passage of the Iliad, the earliest known Greek references to Ionians date only to the late seventh or early sixth century BC. Although the reference in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo may be interpreted as evidence for the heterogeneity of the Ionian population, the Archaic Greek sources on their own do not allow a more precise definition than that they were considered to be Greek.

The Ionian dialect was spoken across the Aegean from mainland Greece to the Cycladic Islands and Asia Minor, and these areas also used a similar version of the Greek alphabet (called the ‘blue’ alphabet, after Adolf Kirchhoff’s colour-coded map of Greek scripts of 1876). Footnote 55 While one can easily agree with Jan Paul Crielaard that dialects do not indicate ‘hard’ ethnic borderlines, Footnote 56 it is clear that the use of the same or similar dialects contributed to a sense of shared identity, both among their speakers and from an external viewpoint. But whether there was such an identity among the Ionians of the late eighth century BC is hard to establish in the absence of relevant sources. External threats may be credited with strengthening the bonds of shared identity, but the Ionians in Asia Minor did not face these, as far as we know, before the Lydian expansion in the sixth century BC. Footnote 57 Most importantly perhaps, the festivals celebrated at the Apollo sanctuary on Delos Footnote 58 and at the Panionion on the north side of Mount Mykale at the mouth of the Meander became the focus of shared cultic activity no earlier than the late eighth or early seventh century BC. Footnote 59

Long before these Archaic Greek attestations and the first Assyrian reference in the 730s BC, some terms appear in textual sources from the Late Bronze Age that have been very tentatively connected to the Greek term Iά(ϝ)ονϵς. An inscription from the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (r. 1390–1352 BC) at Thebes (Kom el-Hettan, block GN) mentions the land of ywnj, which some have understood as ‘Great Ionia’. Footnote 60 Two very fragmentary Linear B tablets from Knossos, one of which can be dated to ca. 1400 BC, Footnote 61 mention a group of people called i-ja-wo-ne. Footnote 62 Although several commentators have assumed a link with Greece and/or the Aegean, Footnote 63 one must stress that these texts are generally too fragmentary and too laconic to allow any conclusions about the nature of these places and/or people(s) and the terms’ connection to the Iά(ϝ)ονϵς of the later Greek sources. The ‘land of YMAN’ (kḥwt yman), mentioned in a 14th-century alphabetic text from Ugarit, was once thought to be of relevance, too, but recent scholarship has largely given up on this idea and generally connects the place to a site in the Bekaa plain. Footnote 64

We return to much safer ground with the Assyrian attestations. In the letter SAA 19 25, the Yauneans are mentioned in the context of a coastal raid on Phoenician settlements in the coastal regions of the newly established province of Ṣimirra. It seems that their tactics were based on quick, surprise raids intended to gather booty while avoiding any confrontation with organized forces. Although this letter is their first appearance in the textual sources of the Assyrian Empire, the authorities seem already familiar with these people, Footnote 65 as there is apparently no need for the governor to explain or contextualize the term ‘Yaunean’ to his king Tiglath-pileser III, who had, of course, campaigned extensively on the Levantine coast in previous years.

Some two decades later, the piratical activities that the Yauneans conducted in the area between Cilicia (Que) and the Phoenician coast (Tyre), as mentioned in the Khorsabad Annals of Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC), must have inconvenienced the Assyrian Empire and its allies considerably, as Sargon came to intervene and engaged them directly in a sea battle in 715 BC:

In ord[er to conquer the Yauneans, Footnote 66 whose home] is situated [in the] m[iddle of the s]ea (and) who from the dis[tant] pa[st] had killed pe[ople of the city of Ty]re (and) [of the land of] Que and […-ed] …, I went down to the sea [in ship]s … against them and put (them) to the sword, (both) young (and) old (lit.: small (and) large). Footnote 67

This intervention was deemed successful by Sargon, who included the following among his royal epithets as given, for example, in the Khorsabad cylinder inscription:

(Sargon,) skilled in war, who caught the Yauneans (KUR.ia-am-na-a-a) in the middle of the sea like fish, as a fowler (does); who pacified the land of Que and the city of Tyre. Footnote 68

While the earliest Assyrian sources mention the Yauneans solely within the regional context of piracy, the situation had shifted by the reign of Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC). Footnote 69 Crucially, Esarhaddon annexed the hitherto independent Phoenician kingdom of Sidon in 677 BC and established an Assyrian province in its territory, renaming the capital city Kar-Aššur-ahhe-iddina, ‘Esarhaddon’s Harbour’. Footnote 70 Now the Assyrian Empire was able to interact directly with people from ‘in the middle of the sea’. In one of his inscriptions, Esarhaddon claims that he received tribute from several countries including contributions from the ‘land of Yaun(a)’ (KUR.ia-man), which, according to Rollinger, reflects the geographical and ideological expansion of the Assyrian world view at this time. Footnote 71 The regular contact with the inhabitants of the Levantine coast, who certainly maintained contacts with the Aegean, Footnote 72 will have contributed to this. With Esarhaddon referencing the ‘land of Yaun(a)’, we might argue that by the 670s BC, the Assyrians had come to associate the Yauneans with a clearly defined region.

This reference also signals prominently that the empire’s relationship with the Yauneans had changed considerably in the course of the early seventh century BC. And, indeed, Yauneans already appear as specialist seafarers employed by Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) in the fleet that he had assembled at Nineveh, which sailed down the Tigris in 694 BC to be deployed in a military expedition to the Persian Gulf. Footnote 73 This reference from Sennacherib’s inscriptions demonstrates the presence of Yauneans at Nineveh, then the capital of the Assyrian Empire, in the context of the military and their involvement in a pet project of the king. It should be stressed that professional soldiers, as these men were, belonged to the higher end of the social spectrum, with a regular income supplemented by bonuses according to performance, and could reasonably hope to acquire land and other resources, as the frequent attestation of military men of varying ranks in Assyrian sale documents shows. Footnote 74 However, what other roles Yauneans may have held in Nineveh at this time must remain speculative. In any case, their presence in the heartland of the empire would have exposed those Yauneans to various aspects of Assyrian cultural practice and also afforded the Assyrian authorities ample opportunities to gain a clearer understanding of the Yaunean homeland.

The references to Yauneans in the Assyrian texts indicate that these people originated from somewhere in the west, beyond the sea, outside the sphere of the Assyrian Empire’s direct control in the late eighth and seventh century BC. Some researchers have attempted to connect the term to specific ethnic groups and/or regions. Footnote 75 One such interpretation sees the Yauneans as inhabitants of Cyprus and perhaps even Cilicia. Footnote 76 However, this is unlikely as Cyprus and Cilicia were two separate, well-defined entities to the Assyrians, who knew them as Yadnana and Que, respectively. Footnote 77

Another interpretation associates the Yauneans with parts of mainland Greece, the Cyclades and Asia Minor, Footnote 78 although the idea of restricting their origins specifically to the west coast of Asia Minor has little to recommend it. Footnote 79 A variant of this interpretation associates the Yauneans with the Greek mainland and the western Aegean, more specifically with Attica or Euboia and the Cycladic Islands. Footnote 80 All hypotheses that connect the term to mainland Greece are strongly reliant on the distribution of Greek pottery in the Levant, supplemented by information in later Greek sources. It must be acknowledged that both bodies of evidence are inherently problematic: the former since the relationship between producer and carrier is hard to establish; the latter as they were at least partly coloured by contemporary political interests.

The interpretation currently favoured among scholars is based mainly on Rollinger’s analyses of the Neo-Assyrian references, presented in several papers published from 1997 onwards. Rejecting the notion that the term denotes a group with a specific common ethnic identity or a connection with a clearly defined geographical area, this view instead understands the term as a collective designation for several linguistic, cultural and ethnic groups deriving from a broadly conceived region located west of Cilicia, where the westernmost province of the Assyrian Empire, Que, was located. Footnote 81 In this interpretation, the Yauneans might include various Anatolian population groups, including Greeks from the west coast of Asia Minor or even as far away as the Greek mainland.

At this point, a few short words are in order on how current research deals with the topic of ethnic labelling. The scholarly debate of the past 40 years has highlighted not only that our modern concepts of ethnic, or cultural, groups are rarely congruent with ancient views, but that past scholarship actively constructed ethnic groups that were not perceived as coherent groups or labelled as such in antiquity, or in certain cases only very late. Footnote 82 At the same time, the debate made apparent that ethnicity must be seen as a fluid concept, with group identities subject to changes initiated by internal or external actors, certain traits often pronounced or suppressed and even appropriated with the objective of excluding or alternatively including certain entities that do not necessarily have any prior connection. Footnote 83 Thus, rather than constituting ethnic markers denoting a shared common history with ‘blood ties’ and a common connection to a specific territory, ancient group labels may often serve to denote social or cultural differences. That being said, we must also acknowledge, as has been stressed by, for example, Nino Luraghi, that ethnic discourse was not without constraints in antiquity: it depended on credibility and was therefore never a complete invention.

A key argument for the proposal to identify the Yauneans not exclusively with one specific ethnic group is the fact that in the later Babylonian documentation of the sixth century BC, people with non-Greek names are designated with the ethnicon LÚ.ia-man-na-a-a. Footnote 84 However, while the Ionian poleis located in Asia Minor were certainly home to a predominantly Greek population, they also counted people with Carian and Luwian names among their number. Footnote 85 One such example from Miletos was Examyes, the father of the philosopher Thales. Footnote 86 Further, the heterogeneity of the population of the Ionian cities can also be deduced from Herodotus’ remarks on the mixed origins of the Ionian settlers in Asia Minor and in particular the anecdote concerning intermarriage with Carian women at Miletos. Footnote 87 Epigraphic evidence from that city demonstrates that its citizens continued to use Carian names even in later periods. Footnote 88 For Smyrna and Samos, too, linguistic heterogeneity is in clear evidence. Footnote 89 Finally, archaeological data confirms that the Greek settlers in Asia Minor preferred to settle in places already occupied by local population groups, which further points to a mixed population in these settlements. Footnote 90

Therefore, when a person with a non-Greek name is described as LÚ.ia-man-na-a-a in a Babylonian text, this cannot necessarily be taken as evidence for the diffuse application of the term to people hailing from a wide geographical area that incorporates everything west of Cilicia. Such references can still be accommodated within an interpretation that sees the term ‘Yaunean’ linked to a more closely defined region in Asia Minor, for example, when one acknowledges and accepts the heterogeneity of the population of the west coast of Anatolia at the time. Footnote 91 Importantly, there is not a single reference to a Yaunean identified by name (Greek or otherwise) in the Assyrian documentation of the eighth and seventh century BC.

If we turn back to these sources, the Yauneans are said to have arrived in the Levant by ship, hence the designation ‘from the midst of the sea’. Furthermore, they are described as pirates, sailors and shipbuilders, frequently mentioned in the same breath as Phoenician population groups with the same expertise (typically as foes but in Sennacherib’s fleet as colleagues). While the attacks and tactics used by the Yaunean raiders according to the Assyrian sources can be easily matched with the descriptions of Greek seaborne raiding in Homer (although the preferred target there seems to be Egypt and not the Levant), Footnote 92 it remains to be established whether there are any Anatolian population groups other than the Greeks who would have possessed the requisite nautical knowledge and know-how to warrant such descriptions in the eighth and seventh century BC.

If we consider the coastal regions west of Cilicia, there is little to suggest that the inhabitants of Pamphylia, Lycia or Caria were renowned for their maritime exploits during that time. Footnote 93 Granted, the written and archaeological records available for the eighth and seventh century BC are very limited. But even if one wanted to explain the lack of evidence with the regional history of research, one would have to concede that neither Pamphylia nor Lycia was connected to maritime enterprises in the Greek sources although people from Lycia (Lukka) are attested in Egyptian and Hittite sources from the Late Bronze Age as seafarers. Footnote 94 As for the Carians, Diodorus Siculus connected them to an eastern Aegean thalassocracy in the mythical time after the Trojan War, Footnote 95 and they appear together with Greeks as mercenaries across the sea in the service of the Saite Dynasty of Egypt in the late seventh and sixth century BC. Footnote 96 However, precisely for the Carians, a separate terminology is attested in the Babylonian sources (Bannēšāya, possibly only for Carians from Anatolia, and Karsāya, used also for Carians who came to Babylonia from Egypt), Footnote 97 and they are therefore unlikely candidates for identification with the Yauneans.

If we compare this with the Greeks, not only does the testimony of the Iliad and the Odyssey highlight the all-important role of the maritime sphere in their lifestyle, but this is matched by the representations of ship and maritime battles scenes on Late Geometric Attic vase painting. Footnote 98 Furthermore, the archaeological record (see above, section II) indicates contacts between the Aegean and the Levant from the tenth century BC onwards at the latest, making untenable any position that excludes active Greek involvement in the East in the eighth and seventh century BC.

V. SAA 19 26: the town of Yauna (URU.ia-ú-na)

As emphasized above (section IV), the term ‘Ionian’ appears in Greek sources only after the earliest Assyrian reference to the Yauneans in SAA 19 25, from the 730s BC. Likewise, none of the evidence hinting at the forging of a shared Ionian identity predates the Assyrian sources mentioning Yauneans.

Some specialists in the Archaic Greek period, notably Christoph Ulf, Jonathan Hall and Peter Högemann, have already suggested that the term ‘Ionian’ originates in external nomenclature, Footnote 99 in parallel to, for example, the name ‘Phoenician’, a Greek term used to classify people from various distinct Levantine polities such as Tyre and Sidon that shared, in the Greek view, enough cultural traditions to merit the use of a wholesale classification. Footnote 100 The name ‘Yaunean’ may have originated in the external terminology used by the Assyrian Empire and its allies for groups of people who came to the Levant across the Mediterranean. Just as the term ‘Viking’ came to signify ‘raider coming across the sea from the east’ in the British Isles during the Early Middle Ages, we could take the term ‘Yaunean’ to mean ‘raider coming across the sea from the west’ for the Assyrian Empire and its Levantine allies in the eighth century BC. Keen to emphasize their communalities in the linguistically and ethnically heterogeneous environment of the eastern Mediterranean, the people so designated may have adopted the term ‘Ionian’ as their self-designation at a time when a desire for constructing an overarching, shared group identity becomes apparent also in the celebration of supra-regional festivals and in mutual aid in times of conflict.

It should be stressed that such a scenario leaves entirely open whether the first western sea raiders to appear on the Levantine coast would have originated in the region that was later defined as Ionian (regardless of whether this is understood to be only the west coast of Asia Minor or also includes the Cyclades and Euboia) or whether they were speakers of the eastern Greek variant called Ionian. It is entirely possible that the eventual Ionians only arrived in the Levant when the name ‘Yaunean’ had already been well established for other Greeks and that they appropriated it because of the considerable prestige locally associated with this term: seafaring expertise, infamous terrors of the sea, cunning raiders of the coasts. However, there is no doubt that from the late seventh century BC onwards, the Ionians of Asia Minor and the Aegean islands indeed constituted the dominant Greek presence in the East.

This raises a key question: if the Assyrian designation ‘Yaunean’ is not an approximation of an existing name, ‘Ionian’, what is the origin of the term? This brings us to the town of Yauna (URU.ia-ú-na) mentioned in letter SAA 19 26, dated likewise to the time soon after 738 BC when the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra was established on the Mediterranean along the same coastline controlled today by Syria. Given Yauna’s name, Rollinger has argued that the Yauneans must have constituted the dominant population within this settlement. Footnote 101 What has not yet been considered is the possibility that the Assyrian term ‘Yaunean’ originally connotated specifically the inhabitants of this town. We will explore this idea further below (section V.ii).

V. Where was Yauna and who were the Yauneans?

i. The location of Yauna

The town of Yauna is only attested in the letter SAA 19 26. After Henry Saggs’ publication of the letter in 2001, Nadav Na’aman was the first scholar to discuss its contents in any detail, in a short note published in 2004 as an addition to a recent article. He concluded that URU.ia-ú-na should be sought in the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra, very tentatively suggesting Ras al-Bassit as a possible candidate for identification and the Jebel al-Aqra (see above, section III) as the ‘snowy mountain(s)’ (KUR-e ša ku-pe-⸢e⸣) mentioned in the letter. Footnote 102 In a 2008 paper on Qurdi-Aššur-lamur, the governor of Ṣimirra and sender of the letter in question, Shigeo Yamada stated that ‘the letter deals with incidents on the northern Syrian coast and a mountain range behind it. Accordingly, the city of Yauna should also be sought in the same region’. Footnote 103 When Rollinger discussed the toponym in a 2011 paper, and again briefly in 2017, he too followed the argumentation of Na’aman, assuming a coastal location of URU.ia-ú-na. Footnote 104 On the other hand, Lane Fox, in a 2008 monograph, rejected Na’aman’s tentative identification of Ras al-Bassit (on the basis that the few Greek sherds excavated there could hardly be considered as evidence for a Greek town) but accepted the identification of Jebel al-Aqra with the ‘snowy mountain’, and offered an alternative localization at Al-Mina, Footnote 105 with its rich Greek pottery imports dating to the eighth century BC (an identification which Na’aman had considered and explicitly rejected). Footnote 106

Lane Fox’s identification of Yauna with Al-Mina must be dismissed for reasons of historical geography. Firstly, Al-Mina is not located in the province of Ṣimirra but in its northern neighbour, the province of Kullania (see above, section III). While Qurdi-Aššur-lamur regularly dealt with Assyrian client rulers outside the provincial system, including the Phoenician neighbours down the coast, Sidon and Tyre (both SAA 19 22–23), and further south the Philistine harbour of Ashdod (SAA 19 28), it would violate the basic principles of Assyrian state administration if he intervened and especially if he took captives in his fellow governor’s province. Footnote 107 Admittedly, Qurdi-Aššur-lamur’s name is broken away and has to be restored as the sender of the letter SAA 19 26, but as there are no letters at all preserved from the governor of Kullania among the Nimrud Letters, it would be hard to argue that the text should be attributed to that official’s dossier instead. Lane Fox did not do so either but in his interpretation simply disregarded the Assyrian administrative map and protocol. Despite Al-Mina’s undoubted wealth of Greek pottery, therefore, the site cannot under any circumstances be considered a contender for identification with Yauna. Footnote 108

Na’aman and Lane Fox, and the other commentators mentioned, relied on Saggs’ 2001 edition of the letter, but Luukko’s 2012 re-edition has greatly improved our understanding of the text. Most importantly, it is now clear that the Assyrian forces, and not some third party, are the attackers of the two towns. Therefore, it is worth reviewing the text in detail. According to his letter, the governor of Ṣimirra sent 400 mercenary troops in his service to raid the countryside, Footnote 109 indicative of the heavy-handed strategies the empire used to maintain control over the population of a recently annexed province (see also below in this section). But the troops were spotted and the targets fled: ‘A guard sa[w] (them and) a cry was sounded. We pursued the[m], and they took to the snowy mountain(s) in front of them’. Footnote 110 The Assyrian forces eventually apprehended some fugitives: ‘We caught (people) from Yauna and from Rēši-Ṣūri’. Footnote 111

Let us first consider ‘the snowy mountain(s)’: note that the Assyrian wording could refer equally to a singular or plural term. In the province of Ṣimirra, there are three candidates for identification with such a landscape feature. Footnote 112 As a general rule of thumb, altitudes of about 1,800m in this region would have four months of snow, from about December to March, while the snow would cover altitudes of 2,500m and above for at least six months, from about November to April. Both Na’aman and Lane Fox thought the Jebel al-Aqra (35° 57’ 9” N, 35° 58’ 9.5” E), the ‘Bald Mountain’ to use its Arabic name, a likely option for the letter’s ‘snowy mountain’, with its peak at 1,736m above sea level. Footnote 113 While the Jebel al-Aqra is therefore seasonally capped with snow, the highest parts of the Lebanon range are covered in snow all year long. With a height of 3,088m, the Qurnat as-Sawdā (34° 18’ N, 36° 7’ E), the ‘Black Peak’ in Arabic, is the highest summit of the Lebanon range and situated just 50km southeast of Tell Kazel, the likely site of ancient Ṣimirra, the capital of Qurdi-Aššur-lamur’s province.

A third candidate is the Jebel an-Nusayriyah (after an old designation for the Alawites that references Ibn Nusayr, the founder of this Shiʿite sect; more recently also called Silsilat al-Jibāl as-Sāḥilīyah, the ‘Coastal Mountain Range’), whose highest peak Nabi Yunus (named after the prophet Jonah) only reaches an altitude of 1,562m, the average height of the range being about 1,200m. Nevertheless, January typically sees at least 20 days of snowfall and the range, which blocks all precipitation coming from the coast, is subsequently covered with snow long into spring. Footnote 114 The Jebel an-Nusayriyah range runs parallel to the Mediterranean coast from Tartus to Latakia, and its main ridge constituted the eastern border of the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra, with the provinces of Hatarikka and ManṢuate situated on its other side; all three were established in the former territory of the conquered kingdom of Hamath. Footnote 115

To summarize, if the ‘snowy mountain(s)’ are the nearby part of the Lebanon range the episode described in the letter could have taken place any time in the year, as the peaks there are covered with snow permanently. On the other hand, if this refers to the Jebel al-Aqra or the Jebel an-Nusayriyah, then it would have happened during the winter months or early in spring.

To the Assyrians, Jebel al-Aqra was the holy mountain Ṣapūnu and the Lebanon range was called Labnāna, famous from literature and poetry as well as frequent entries in the royal inscriptions. Footnote 116 There is no reason to replace the name of either of these formidable landmarks with the descriptive designation ‘snowy mountain’. The visually less impressive Jebel an-Nusayriyah, on the other hand, did not carry a name that rang across the wider region in quite the same way. We actually do not know its contemporary designation, although the city of Bargâ on its eastern flank seems to have lent the range its name, at least in later times (Mons Bargylos). Footnote 117 On the other hand, if the letter was written at some point in the first months of the year, the Assyrian governor and his secretary-scribe could have relied on the fact that the king, who knew the area well from his campaigns, would understand this description as simply referring to the higher altitudes that fringed the entire eastern border of the province Ṣimirra. On balance, we consider the Jebel an-Nusayriyah range the best option for identification with the ‘snowy mountains’, a location to which the inhabitants of any settlement along the coast between Tell Kazel in the south and the general area of Latakia in the north could have fled if there was danger in the coastal plains.

After reporting the capture of the fugitive people of Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri, the governor continues: ‘I have sent 200 men to the commander-in-chief, who says that they should be brought to the palace’. Footnote 118 This makes it abundantly clear why the people had fled from the governor’s forces. The purpose of the raid was to draft troops from the local population of the newly established province, whether they came voluntarily or not. Such recruitment by force (impressment) was certainly much needed to bolster the numbers of the Assyrian army in the heyday of the empire’s expansion, when Tiglath-pileser III waged war on all the borders of his realm, resulting in the tripling of the territories under his direct control after two decades of permanent conquest. The letter does not give the total number of press-ganged individuals. Of these, however, the governor of Ṣimirra had selected 200 men for the commander-in-chief (Assyrian turtānu). As a provincial governor, Qurdi-Aššur-lamur was subordinate to the commander-in-chief, one of four imperial ‘super governors’ with supra-regional power of command. Footnote 119 Whether Nabû-da’’inanni, who held this office at the time, Footnote 120 was at his residence in Til Barsip, the capital of the border march of the commander-in-chief on the Euphrates, or whether he was heading a military campaign nearby (as the mid-730s were devoted to the conquest of the kingdoms of Damascus and Israel) is not clear from the letter, but would, of course, have been known to Tiglath-pileser III, to whom the letter was addressed. In any case, the commander-in-chief did not want to deploy the 200 recruits in the west but wanted them sent on to the palace, that is, the royal residence in the empire’s capital Kalhu. Their number is only of limited use to assess the size of the settlements as the governor was likely charged to draft 200 troops, regardless of how many men he captured in total. His letter continues: ‘24 men have died here. There are (also) some who were seized by the chariotry’. Footnote 121 It is not clear whether this refers to the new recruits or to the troops already under the governor’s control; in any case, the king was to understand that death and the demands of the Assyrian chariotry were responsible for further diminishing the manpower available to him.

It is important to stress that this entire episode is framed by the governor’s report on the ongoing construction of elaborate city defences consisting of walls and moats, certainly for the provincial capital. Footnote 122 The purpose of the letter is to explain delays that have been questioned by the king, and the governor’s explanation hinges on the shortage of manpower and the difficulties in managing the workers: the fragmentary passage at the beginning of the letter mentions men working in iron shackles. Footnote 123 By stressing that he had not been able to draft men from Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri without opposition, but instead had to mount a manhunt into dangerous terrain, he explained both the delays in his construction works and made an indirect plea to be excused from any further impressment initiatives on behalf of the empire: the local need for manpower, the king was to understand, was more pressing right now.

Let us now return to the location of Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri. Without doubt, both places lie in the territory of the newly established province of Ṣimirra, and therefore somewhere south of the Jebel al-Aqra and north of the Nahr al-Abrash. At least one thing is certain: the name of Rēši-Ṣūri, which contains the element rēšu (‘head, cape’), unequivocally signals this site’s coastal location. This settlement is also attested in the inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III, which confirm its position somewhere between Ṣimirra in the south and Mount Ṣapūnu (Jebel al-Aqra) in the north. Footnote 124 Na’aman convincingly argued that the Bronze Age settlement Ra’šu, known from texts from Ugarit, was newly founded in the 13th century BC as a Tyrian colony (hence the new name Ra’š-Ṣūri/Rēši-Ṣūri ‘Cape of Tyre’), under which name it is attested in sources from Ugarit and later Assyrian texts. Footnote 125 Na’aman assumed a location near Ugarit and considered two prominent capes (raʾs in Arabic) as candidates for identification; he excluded Ras al-Bassit on the (not entirely convincing) grounds that its archaeological stratigraphy would make it unsuitable for identification with a settlement that kept its name from the 13th to the eighth century, and opted therefore for Ras Ibn Hani, Footnote 126 a suggestion that we find convincing. Nevertheless, two more capes in the region also merit some consideration: Ras al-Fasri, 20km north of Latakia at the modern town of Burj Islam (35° 41’ N, 35° 48’ E), and Qal‘at ar-Rūs (35° 25’ 6” N, 35° 55’ 0” E), 14km south of Latakia on the northern edge of the Jableh plain. All four capes have been proposed as the possible site of Rēši-Ṣūri. Footnote 127 Regardless of which option is ultimately correct, because of its connection to Ugarit in the Bronze Age, the settlement of Rēši-Ṣūri is extremely likely to be found on the northern coastline of Ṣimirra.

Depending on how close to Rēši-Ṣūri we assume Yauna to have been located, our options for identification differ. As we have already discussed, the reference to the ‘snowy mountain(s)’ is of limited help in this regard. Only if we assume that this description refers to Jebel al-Aqra, would Yauna have to be located close to this peak; given Rēši-Ṣūri’s position somewhere near Ugarit, fleeing to the snowy peaks of the Lebanon range was certainly not an option. But our preferred alternative, as argued above, is the Jebel an-Nusayriyah range, whose location offers no indication of whether the settlements are situated in the northern or the southern part of Ṣimirra, as the mountain range runs along the entire eastern border of the province. Nevertheless, given that people from Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri were captured together in the ‘snowy mountain(s)’, one could assume that they all heard the warning sounded by the same watch and fled at the same time, which would imply that the two towns should be located not too far away from each other. Footnote 128 This line of argument would then necessitate the assumption of a northern location also for Yauna. However, if the phrasing were to be understood as the starting point of a chain reaction that led to the flight of the inhabitants of these two settlements, the geographical proximity between Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri perhaps need not have been quite so great. We will return to this point once more at the end of this paper (section VI).

ii. Yauna and the Yauneans

Given that URU.ia-ú-na and KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a appear in the dossier of the same governor, one should consider any argument that seeks to disassociate the two terms as futile. It is standard practice in the Assyrian language to add the nisba -āya to a toponym to designate that place’s inhabitants. Footnote 129 Therefore, within the geographical context of the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra, within the chronological context of the 730s BC and within the archival context of the letter dossier of Qurdi-Aššur-lamur, the Yauneans must surely be the inhabitants of the town of Yauna. This, in turn, implies a coastal position for the settlement, as the letter SAA 19 25 presents the Yauneans as seaborne raiders of Phoenician towns (see above, section IV).

We certainly are not arguing that all of the attestations of the Yauneans in the Assyrian sources refer exclusively to people from URU.ia-ú-na (whatever the origin of this toponym), Footnote 130 as in later attestations (see below and above, section IV), the Yauneans’ home was clearly understood to lie beyond the direct reach of the Assyrian Empire. But half a century earlier, in the turbulent times of the 730s when Tiglath-pileser III had annexed the Syrian coast, to him and his administration, the Yauneans were most likely simply the people of Yauna, a coastal town that now lay in the territory claimed as the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra. The local governor found them to be unwilling and troublesome subjects of the Assyrian crown as they resisted impressment and raided the Phoenician allies’ settlements further south without his authorization.

Bearing in mind that the origins of the term Iά(ϝ)ονϵς are unclear, that all supposed Bronze Age attestations are questionable and that one of the very earliest certain attestations is specifically for a town called Yauna, the obvious interpretation is certainly to see the term ‘Yaunean’ as originally a designation for an inhabitant of that town on the Levantine coast. It is only because of the knowledge of hindsight that we are not content with this simple definition. Twenty years later, the Yaunean pirates attacking Tyre and Que (Cilicia) were described in the inscriptions of Sargon II as people ‘whose home is situated in the middle of the sea’ (see above, section IV), Footnote 131 and the term therefore surely no longer referred only to the crown’s own recalcitrant Ṣimirrean subjects with a taste for boating and a sideline in raiding. But otherwise, there is continuity to be observed in the description of the Yauneans of the 710s BC: they were still pirates who targeted Phoenician settlements. By then, we can argue, the Assyrian nomenclature used the term more widely for certain people with a maritime lifestyle who notably were not Phoenician themselves or members of any other ethnic group originating in the Levant. We have no idea about the fate of the town of Yauna at that time and are entirely ignorant of whether its inhabitants were still going on raids (possibly even with the approval of the Assyrian crown), whether they had settled in their expected role as loyal subjects of the crown or whether they had been so difficult that they had come to be dispersed across the holdings of the empire as unwilling participants in the large-scale resettlement practices that formed the core of Assyrian population management. Footnote 132

Returning to our previous discussions of the emergence of a shared Ionian identity, the establishment of a permanent settlement such as the town of Yauna in the multilingual, multicultural Levant would surely have stimulated the development of a specific Ionian identity more readily than seasonal raiding, which would have involved only limited contact with the local population. Footnote 133 On the other hand, permanent settlers from the west, encountered when the former holdings of the kingdom of Hamath on the Syrian coast were integrated into the empire’s administrative system, would certainly have left a deeper impression on the Assyrian authorities and a better understanding of this population group, and this would likely have encouraged labelling others ‘like them’ with the designation already in use for these settlers. Hence, we see the origin of the Assyrian term ‘Yaunean’ (KUR.ia-ú-na-a-a, KUR.ia-man-a-a, KUR.ia-am-na-a-a) in the toponym URU.ia-ú-na. While this name is certainly not Semitic, its origins and meaning remain otherwise unclear.

VI. In conclusion: Yauna, its foundation and its location, once again

While Greek pottery imports reached the Levant from the tenth century BC onwards, the amounts are limited before ca. 750 BC, indicating only sporadic contacts for that period. Furthermore, the archaeological contexts, together with the amounts of pottery recovered so far, seem to point to eastern rather than Greek initiatives. From 750 BC onwards, however, the amounts of Greek imports increased notably, at least at Al-Mina, today still the site with the most significant amounts of Greek pottery found in northern Syria, and this indicates regular exchange contacts between the Aegean and the Levant. Footnote 134 At the same time, increasing amounts of Near Eastern imports arrived in the Aegean, especially at sanctuaries located along the sea traffic lanes such as the Heraion of Samos. Footnote 135 The surge of Greek pottery in the East was therefore matched by the rise of Near Eastern imports in the Aegean and mainland Greece. Furthermore, maritime enterprises feature prominently in Greek epic while sea battles and ship scenes seemingly played a role in the construction of male role models, as can be seen on Greek Geometric vessels after ca. 770 BC. Footnote 136 All these indicators demonstrate the importance of seamanship for the Greeks in general and may suggest an intensification of contact between the Aegean and the Levant. It is these developments that form the likely background for the foundation of the permanent settlement of Yauna in northern Syria.

The most probable time horizon for this settlement’s foundation (wherever its precise location) is therefore around ca. 750 BC, and in any case before 738 BC, when the Assyrian Empire gained control over the Syrian coast and Qurdi-Aššur-lamur took office as governor of Ṣimirra, mentioning the town of Yauna by name in his correspondence with his king. This puts the event in the time that is generally considered a ‘renaissance’ for Greece (possibly having started already earlier in the eighth century BC) when we can observe indications of population and economic growth, Footnote 137 in addition to increasing contacts between the Aegean and the Near East.

Yauna was presumably founded as a trading settlement or port of trade with the permission of the erstwhile local power, the kingdom of Hamath, which had no maritime traditions or ambitions of its own despite the existence of several sites ideally suited to be ports within its territory. Footnote 138 While it is inconceivable that the settlement was primarily intended as a hideout for pirates, a sideline in opportunistic raids is likely to have been condoned by Hamath, and perhaps even encouraged, as long as these targeted the Phoenician ports that typically supported the interests of the Assyrian Empire rather than the alliances that Hamath organized with the kingdom of Damascus against the superpower. Such an arrangement would allow the rulers of Hamath to share in the profits while simultaneously allowing them to deny any involvement in these raids. In any case, leaving speculation aside, the gradual Assyrian annexation of the wider region changed the local power structures profoundly. In the 730s BC, when the empire conquered and integrated as provinces the first stretches of the Levant, the newly incorporated subjects of the Assyrian crown at Yauna would have come to realize that their new overlord did not condone such activities against the empire’s allies.

This brings us back to the sites in the coastal territories of Hamath, and later in the Assyrian province of Ṣimirra, where excavations have produced finds of Greek pottery (see above, section II). We must exclude Tabbat al-Hammam, as it is situated less than 10km from Tell Kazel and is therefore too far from the target area to merit serious consideration. Footnote 139 Given that of all the north Syrian coastal sites between the Jableh plain and the Jebel al-Aqra, only Ras al-Bassit, Ras Ibn Hani and Tell Sukas have thus far revealed material evidence that can be classified as Greek, we will start by briefly reviewing the material from these three sites, bearing in mind that, with Na’aman, we favour identifying Ras Ibn Hani as Rēši-Ṣūri, the ‘Cape of Tyre’.

Importantly, the available evidence for the relevant period is limited to Greek pottery at all three sites. Any other currently known materials, such as the Greek burials and Greek graffiti that have been reported for Ras al-Bassit and Tell Sukas, date to the end of the seventh or the early sixth century BC. Footnote 140 The only possible exception is the sherd of a Late Geometric or early seventh century BC cup from Ras al-Bassit, which has a graffito incised that may be the Greek letter ēta (although an interpretation as the Phoenician letter het is equally feasible). Footnote 141 Furthermore, the possibility of Greek cult activities taking place before the sixth century BC or the building of a Greek temple at Tell Sukas (during Sukas Phase G3, dated to 675–588 BC), as suggested by Poul Jorgen Riis, was convincingly rejected by Jaqcues Perreault. Footnote 142 All excavated architectural remains found at Tell Sukas for the period under consideration point to local traditions, with the exception of the roof tiles, but these probably do not predate the sixth century BC. Footnote 143 Therefore, in the absence of any architectural remains or other finds pointing to Aegean cultural traditions for the late eighth century BC, we are left only with pottery sherds, which most modern scholars would generally see as a poor indicator for the ethnic identification of a settlement’s inhabitants. Footnote 144 Moreover, the Greek ceramic imports dating to the eighth century BC at all three sites are strictly limited to fine painted pottery and consist largely of what some scholars would interpret as high-status vessels used for feasting whereas undecorated vessels or everyday cooking pots (which some consider a more reliable marker of ethnicity) Footnote 145 are entirely missing. Footnote 146

Furthermore, it is surprising that to date no local imitations of Greek pottery produced in the Levant and dating to the eighth or early seventh century BC have been identified. The so-called ‘Al-Mina Ware’ found at some sites in the Levant and Cilicia (for example, Soloi, Tarsus, Kinet Höyük, Ras el-Bassit and Sukas) was probably produced at Salamis on Cyprus. Footnote 147 Moreover, the possible local imitations of Greek pottery, as suggested by Rosalinde Kearsley, turned out to be Euboian in origin. Footnote 148 It was not until the second half of the seventh century BC that Greek pottery was imitated in the Levant, with Kinet Höyük constituting one known production centre. Footnote 149 This lack of locally produced imitations can be considered another argument against any substantial presence of Greeks in the East but may also be an indication of a specific consumer behaviour. After all, outside of Al-Mina, and perhaps some Phoenician cities that are less well documented, Greek pottery remained a rare commodity in the Levant, at least until the end of the Archaic period.

Given this situation, the analysis of Greek pottery becomes central to the arguments advocating Greek presence in the East or in the wider Aegean more generally. While the presence of Greek pottery does not automatically entail the presence of Greeks, analysing the contexts in which Greek pottery appeared holds particular importance since this would allow us to identify certain behavioural patterns associated with Greek pottery that may be distinctive for certain social or cultural groups. Footnote 150 Unfortunately, these contexts have rarely been recorded during excavation, and a detailed documentation of the context is of course the crucial prerequisite for any analysis. One example that highlights the problem of working with insufficiently documented records is Kearsley’s 1995 study, in which she included an interpretation of pottery sherds from a house unit at Al-Mina. Footnote 151 Her results are partly misleading because they are based on a selective sample. Further, she ignored possible post-depositional processes on a site that has demonstrably been rebuilt several times in its occupation history, which can lead to ceramic assemblages entailing material from several phases, and perhaps even different house units. Footnote 152 While Kearsley’s attempt provided us with valuable insights into the various origins of the objects, the documentation of the find context, or rather the lack of it, offered no indication of the practical use of the vessels. More generally, undisturbed contexts have only been recovered at a few Levantine sites where Greek Late Geometric pottery has been identified and that have been excavated at a standard that would permit a contextual interpretation of the use patterns. Footnote 153

Beyond these key methodological issues, our assessment is further hampered by the obstacles presented by publication quality and/or status as well as the quality of the recording systems used for finds, which vary considerably across the three sites. The known Iron Age architectural remains from Ras Ibn Hani date from the 12th to the 11th century BC, and no architectural features from the later Iron Age have been uncovered so far, this period solely represented by finds; but while final excavation reports have long been available for the Bronze Age remains uncovered at Ras Ibn Hani, a detailed report of the site’s Iron Age finds still awaits publication. Footnote 154 Despite the extensive and well-documented excavations at Tell Sukas, only a fraction of the excavated material was recorded and subsequently published. Footnote 155 Lastly, at Ras al-Bassit, while the final report on the full material evidence of the Early Iron Age settlement still awaits publication, preliminary reports suggest that the pottery published so far offers only restricted insight into the material available from the site. Footnote 156

When focussing now on the evidence presently available, 25 fragments of Greek ceramic imports have so far been reported for Ras Ibn Hani, and a date in the second half of the eighth century BC is only feasible for five of these pieces. Footnote 157 At Tell Sukas, the eighth-century evidence for Greek pottery is slightly less meagre but still very limited: of the 341 published pieces, only three date to the Middle Geometric period while a date of around 750–675 BC is feasible for only ten pieces. At Ras al-Bassit, the incomplete data available to date consists of only 43 Greek ceramic imports from the settlement and the necropolis, of which 11 fragments can be attributed to the second half of the eighth or the early seventh century BC. Footnote 158 Although the incomplete publication status of the material from the settlement of Ras al-Bassit precludes any final assessment, the published remains from the cemetery would argue against any presence of Greeks before ca. 600 BC. Footnote 159

Accepting that due to its name and the available written evidence, Rēši-Ṣūri must be a settlement on Ras Ibn Hani or another of the capes near Latakia and assuming that the nearby town called Yauna attested in a document dating to the 730s BC should yield some sort of material evidence for a Greek presence in the second half of the eighth century, Ras al-Bassit and Tell Sukas may at first appear to be the only possible candidates for identification with Yauna. Yet, further clues can be deduced from the occupation history: after the Late Bronze Age settlements at these two sites had previously come to a violent end, both were reoccupied at some point already in the Early Iron Age. Otherwise, specific interruptions in their settlement history that might have allowed new arrivals on the shores of northern Syria to settle there and that would broadly coincide with the suggested foundation date of the town of Yauna could not be identified in the archaeological record. On balance, the discussions above indicate that it is improbable that Yauna can be identified with either Ras al-Bassit or Tell Sukas.

However, in the general area where the town of Yauna must be sought, there are several other places suitable for locating a hitherto unidentified Iron Age coastal settlement, some of which are certain to have been settled in antiquity. Indeed, there are several such sites in the coastal area just north of Ras Ibn Hani, the likely location of Rēši-Ṣūri, some known from written sources, and others from limited excavation or survey activities.

If we look at the testimony of the literary sources, the first place is ancient Heracleia, whose earliest appearance is in Strabo (16.2.8) and which is then mentioned in Pliny (HN 5.79), Ptolemy (5.15.3) and in the Stadiasmus Maris Magni (138, 142), Footnote 160 with all references indicating its location between Latakia and Poseideion (as discussed above, section II, likely to be identified with Ras al-Bassit). A weight found at modern Burj Islam, around 20km north of Latakia, bears a Greek inscription dated to ca. 108/7 BC that mentions a ‘Heracleia at the sea’, which could well be identical with the literary sources’ Heracleia and serves as a further indication of this settlement’s location in the vicinity of Ras Ibn Hani. Footnote 161 Although Heracleia does not appear in the literary sources prior to the late Hellenistic period, we must not rule out an earlier occupation of the settlement, perhaps under a different name. Even less is known about a settlement called Charadrus, which is also mentioned in the passage in Pliny just cited, where it is located between Heracleia and Poseideion, and (in a slightly different spelling) in the Stadiasmus Maris Magni (144). Footnote 162 Pasieria is another coastal town in this part of northern Syria that is only known from the Stadiasmus Maris Magni (140) and has been linked to the cape of Ras al-Fasri (just north of Burj Islam). Footnote 163 While the site was certainly occupied in late Roman times, as indicated by a few archaeological finds, nothing about its earlier settlement history is known. Finally, according to Pliny (HN 5.79), a further town called Dipolis was located between Latakia and Heracleia, which highlights how many suitable settlement places existed along a short stretch of the northern Syrian coastline.

If we now turn to the known archaeological sites in the region, there is Tell Barsuna, which was occupied in the Late Bronze Age according to the results of the brief excavations undertaken in 1958. Footnote 164 Although its settlement history remains mostly unknown, the site is not situated directly on the coast and should thus be excluded as a potential location for the town of Yauna. Footnote 165 However, not far from Tell Barsuna there is a possible anchorage point for ships and an adequate location for a settlement at the outlet of the Nahr al-Arab near the modern town of Al-Shamiyah, although so far, no archaeological finds have been reported from there.

We must certainly also consider Minet el-Beida, known under the name Mahadu as the port of Ugarit in the Late Bronze Age and later in Classical times as Leukos Limen. Footnote 166 While this port site has been more extensively excavated than most of the others previously discussed, it has not yet been explored exhaustively. Given the presence of the natural bay and its suitability for safe anchorage, it would be very surprising if there were indeed a long gap in its occupation after the destruction of Ugarit. Footnote 167 The region between the cape of Ras Ibn Hani and Minet el-Beida constitutes another area of potential interest for seafarers looking to settle, especially as, during the Early Iron Age, the settlement of Ras Ibn Hani seems to have been limited to the promontory. Therefore, anywhere on the coast between Ras Ibn Hani and Ras at-Tamrah/Wadi Jahannam could potentially be seen as the site of a new, as yet unidentified Iron Age foundation.

South of Ras Ibn Hani, there are two known archaeological sites of relevance in the area of the modern city of Latakia: the small island called Gazira Mar Tatrus (about 4km north of Latakia) and, close by but inland, the site of Damsarhu. Both places have so far seen only limited exploration, also due to the urban spread of Latakia, which makes archaeological work difficult. At Damsarhu only Chalcolithic finds have been identified, Footnote 168 while Gazira Mar Tatrus was occupied from the Iron Age onwards. Footnote 169

All these places around Ras Ibn Hani could be possible settlement sites for potential newcomers in the region. They all provide anchorage suitable for seafaring ships, a key qualification that would have made it attractive for Greeks to found settlements there. While it is possible that many of these sites were indeed settled only in the Hellenistic period and later, the patchy archaeological record currently available to us leaves much room for hypothesizing about the situation in the Early Iron Age.

So far, we have only looked at sites close to Ras Ibn Hani. The main reason for this is that, according to letter SAA 19 26, the inhabitants of Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri were able to flee ‘to the snowy mountain(s)’ after a guard saw the Assyrian force’s approach and sounded a warning, which would seem to suggest relative proximity of these settlements to each other. However, if the phrasing (for which see above, section V.i) is interpreted to refer to a single event that set off a chain reaction resulting in the flight of the inhabitants of Yauna and Rēši-Ṣūri, then we should also consider the coastal sites in the Jableh plain as potential locations for the town of Yauna.

Even though the Jableh plain has a rich settlement history and many sites are relatively well explored and excavated (for example, Tell Tweini, ancient Gibala), Footnote 170 none of the coastal sites have been properly studied, with the exception of Tell Sukas. Among the potential coastal sites, we can certainly list Qalʿat ar-Rus and Beldi al-Milk, and possibly also the outlet of Nahr ar-Rumaila near Tell Tweini. In addition, there are further suitable small bays and creeks, but none of these have so far revealed any settlement evidence. Footnote 171

Starting at the northern edge of the Jableh plain, Qalʿat ar-Rus is situated at the Nahr ar-Rus river and tentatively identified with the Bronze Age settlement of Attalig; it has an occupation history that stretches back to the Chalcolithic period and has also yielded evidence for an Iron Age occupation. Footnote 172 With the Nahr ar-Rus flowing into the Mediterranean at the site, a small cape forms a bay that protects ships from southern winds. Thus, the site would have been an excellent choice for settlers pursuing maritime activities. Given the very limited excavations carried out at the site so far, we cannot say anything about the situation in the eighth century BC. The outlet of the Nahr ar-Rumaila, located only about 3km further south and in close proximity to Tell Tweini (its inland position and well-understood occupation history disqualifies it from identification with Yauna), offers similar features but apart from stone quarries and ‘some ruins’, the small bay there has not yet revealed any evidence of a settlement. Footnote 173

Situated at the southern end of the Jableh plain, the ruins of Beldi al-Milk, part of the modern coastal village of Arab al-Milk, are likely to be identified with the ancient town of Paltos (that name surviving in the first element of the Arabic toponym). Footnote 174 Paltos is one of the few sites in the Levant for which literary evidence indicates that the settlement was known to Greeks early on, probably already in the Archaic period: the town is mentioned in a scholion of Simonides of Keos (ca. 557/6–468/7 BC). Footnote 175 Situated at the Nahr ar-Sinn, Beldi al-Milk offers good natural conditions for seafarers and probably functioned as a harbour in antiquity: Riis considered it to be the possible port of nearby Tell Daruk (probably ancient Usnu/Ušnatu), which was occupied from the Late Bronze Age onwards. Footnote 176 The occupation of Beldi al-Milk goes back to the Late Bronze Age, too, and it seems that it was also settled during the ninth and eighth centuries BC. Footnote 177 Again, the limited archaeological work carried out so far must discourage us from drawing any detailed conclusions about the specific occupation history of the site. As also Qalʿat ar-Rus, Beldi al-Milk has not revealed any Greek finds dated to the eighth or seventh century BC so far. Moreover, with the etymology of Paltos convincingly explained as Semitic, Footnote 178 it is unlikely to have been a Greek settlement. All these coastal sites in the Jableh plain were linked by an ancient road, Footnote 179 and if identifying Yauna with any certainty continues to prove difficult, it was certainly this road that led the troops of the Assyrian governor of Ṣimirra northwards on their mission to press locals into armed service.