The two groups of explanatory factors contained in the theoretical framework – institutional factors and issue characteristics – influence blame game interactions in important ways. The previous chapters demonstrate that there are important interaction effects between institutional factors and issue characteristics. For example, whether or not incumbents deflect blame depends both on the availability of scapegoats in a particular institutional context and on the strength of public feedback to a particular controversy type, as incumbents only deflect blame if public pressure forces them to do so. Given that blame deflection implicitly acknowledges that someone caused a problem for which blame must be allocated, incumbents are usually eager to contest the existence of a problem for as long as possible. Another example is the degree of activism adopted by incumbents, which depends on both the strength of public feedback and on the shape of institutional blame barriers.

In this chapter, I will look at these interaction effects in more detail. To obtain a comprehensive picture of blame games, I will examine how institutional factors and issue characteristics combine to produce blame game consequences. This examination begins by reconsidering the role of citizens during blame games. Akin to the spectators of a boxing match, citizens observe a blame game with more or less interest and passion, they eventually take sides with one of the combatants, and they form an opinion on who they believe should win. As we have seen, the public’s attitude toward a blame game influences blame game interactions in important ways. But whether and how this attitude leaves an imprint on the consequences of the blame game is a different question. In a perfectly democratic world, we would expect that strong public feedback translates into extensive blame game consequences that are largely in line with the preferences of the majority of the public on that particular controversy. Weak public feedback would mean only minor consequences because the majority of the public would not see a need for significant changes. However, we have reason to expect that political systems do not just ‘pass through’ public feedback, but weaken, divert, or altogether stall it during blame games.

In order to better understand the transmission of citizen preferences during blame games, one must assess whether and how public feedback to a particular controversy leads to blame game consequences. In other words, one needs to analyze interaction effects between institutional factors and issue characteristics to understand how public feedback translates into reputational and/or policy consequences. To answer these questions, I construct a typological theory of blame games and their consequences (Collier et al., Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012; George & Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005). A typological theory develops “contingent generalizations about combinations or configurations of variables that constitute theoretical types” (George & Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005, p. 233). A typological theory helps to handle and structure a complex empirical reality and allows me to move up the ladder of abstraction and consider blame games and their consequences in their entirety after a dense empirical analysis that focused on establishing the influence of individual contextual factors on blame game interactions.

8.1 Constructing a Typological Theory

To begin with, I use the strength of public feedback and the extent of consequences to construct a property space consisting of four blame game types (see Table 11). Blame games can exhibit weak public feedback and limited consequences, strong feedback and limited consequences, weak feedback and extensive consequences, and strong feedback and extensive consequences. In a second step, I categorize the nine blame games studied in detail along those dimensions to assign them to one of the four blame game types.1 To do so, I establish empirical thresholds that allow me to distinguish weak from strong feedback and limited from extensive consequences. The procedure that I apply here is called ‘pragmatic compression’ or the “collapsing [of] contiguous cells if their division serves no useful theoretical purpose” (Elman, Reference Elman2005, p. 300). From a broader perspective, what ultimately interests me is whether or not a blame game was a venerable political scandal, whether it was just a hiccup in the trajectory of a public policy, or whether it significantly altered its trajectory. The dichotomization focuses on these broader issues, and it captures the aspects of the empirical reality that are relevant at this point in the analysis (but not more in order to avoid complicating it).

Table 11 Relationships between public feedback and blame game consequences

| Limited consequences | Extensive consequences | |

|---|---|---|

| Weak public feedback | METRONET, DOME, EXPO | DRONE, TAX, BER |

| Strong public feedback | CSA | NSU, CARLOS |

Obviously, these dichotomizations lead to a loss of information and involve tricky decisions (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). For example, I need to consider temporal factors such as looming elections or unusual personal involvement, which lead opponents to more heavily invest in blame generation and that, consequently, may lead to stronger feedback than a particular controversy type alone would suggest. Similarly, I must consider that some controversies are so intricate that incumbents cannot boldly address them, even if they want to. In these cases, the consequences of a blame game are not only produced by the interplay of issue characteristics and institutional factors, but they also depend on other controversy-related factors. However, extensive case knowledge allows me to transparently address these measurement problems. Reducing the risk of mistaken inferences by relying on detailed within-case evidence is seen as a decisive advantage of typological theorizing over purely comparative approaches (George & Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005, p. 254).

To distinguish weak from strong public feedback, I draw on the measurements conducted in the case studies in Chapters 3–5. An overview of these measurements and the categorizations that result therefrom can be found in Table A3 in the Appendix. The case studies reveal that public feedback to distant-salient blame games (CSA, NSU, CARLOS) is significantly stronger than feedback to distant-nonsalient blame games (DOME, DRONE, EXPO). Accordingly, I assign the three distant-salient blame games to the ‘strong feedback’ category and the distant-nonsalient blame games to the ‘weak feedback’ category. I also assign proximate-nonsalient blame games to the ‘weak feedback’ category since the feedback measured in the METRONET, BER, and TAX cases was still rather moderate and the difference in feedback intensity compared to distant-salient blame games was much larger than the difference to distant-nonsalient ones.

To distinguish blame games without consequences from rather consequential blame games, we must contrast the types and degrees of consequences found in the nine cases. Measurement details for each case can be found in Table A4 in the Appendix. The two main categories of blame game consequences are reputational consequences and policy consequences. Reputational consequences encompass the resignations of actors somehow involved in the controversy, ranging from incumbent politicians to administrative actors. While the resignations of political incumbents could only be observed in the CARLOS and BER cases, resignations of administrative actors were more widespread. I weigh political resignations higher than administrative resignations. One of opponents’ main goals during blame games is to put political incumbents under pressure (either to bring them to resign or to give in to their policy demands). While bureaucratic resignations can be portrayed by incumbents as mere hiccups in the administrative regime, political resignations reveal that incumbents had to assume political responsibility for a policy controversy, and they also satisfy a feeling of vindication among the affected public (interpreted as a form of ‘responsiveness’ to the public’s demands). Policy consequences encompass changes and adaptations to the policy at the heart of the controversy. The case studies revealed that blame games do not usually lead to sweeping policy change. Put differently, opponents rarely reach all their policy goals during a blame game. However, as observed in the TAX and DRONE cases, blame games can exhibit more subtle policy consequences. Even if opponents’ blame generation does not lead to immediate policy change, it may still anchor a controversy in collective memory. Opponents can then draw on collective memory to generate public feedback during a subsequent round of conflict. The previous controversy thereby serves as an anchor that influences subsequent public reactions (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). In other words, blame generation may lay the groundwork for stronger public feedback in the future and thereby paves the way for lagged policy consequences. Therefore, I treat cases that have consequences resulting from an anchoring effect as blame games with extensive consequences. Moreover, I treat the relationship between reputational and policy consequences as one of ‘arithmetic addition’, that is, the aggregate level of reputational and policy consequences determines whether consequences are ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006). This approach is warranted because, depending on the particular controversy, the public may not only be interested in policy consequences but also in the punishment of incumbents.

Overall, the variation in consequences across cases suggests that we must set a rather low threshold for distinguishing blame games with limited consequences from blame games with relatively extensive consequences. Even by setting a low threshold, however, there are clear cases of blame games with very limited consequences in the sample, namely the CSA, METRONET, DOME, and EXPO cases. At the other end of the spectrum, we have clear cases of blame games that have extensive reputational and/or policy consequences, namely the NSU, DRONE, CARLOS, and TAX cases. The only case that is trickier to assign is the BER case. The idiosyncratic nature of the policy problem at the heart of this blame game made it impossible for incumbents to boldly address the problem. When the blame game started, it was already too late for incumbents to terminate the construction of the airport or to significantly adapt its implementation structure due to contractual commitments. Hence, we ultimately do not know whether incumbents deliberately opted against bold policy change or whether they wanted to boldly address the controversy but were unable to do so. Three reasons make me treat the BER case as a blame game with extensive consequences. First, several public managers had to resign. Second, the controversy ultimately cost the mayor his political career. And third, evidence suggests that incumbents did everything in their power to open the airport as soon as possible.

8.2 Political Systems and How They Manage Policy Controversies

A look at the distribution of cases across the cells in Table 11 reveals an important insight. All four blame game types are empirically present in the case sample. This means that there is no perfect match between strong public feedback and extensive consequences on the one hand, and weak feedback and limited consequences on the other. Instead, the relationship between public feedback and blame game consequences is more complicated. Table 11 reveals that there are blame games where feedback is limited but that produce extensive consequences (BER, DRONE, TAX), and that there is a blame game in the sample where feedback is strong but consequences are limited (CSA). This suggests that there must be interaction effects at work between a controversy (and the public feedback to it) and the institutional system in which it is processed that lead to rather counterintuitive blame game types.

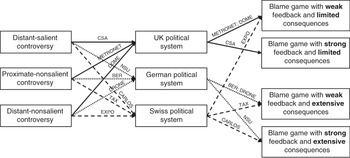

To expose the interaction effects that produce the four blame game types, I adopt a more procedural perspective, transforming this typology into a causal diagram, as pictured in Figure 3 (George & Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005, chapter 11). On the right side of Figure 3, there are the outcome boxes, one for each of the four blame game types found in the sample and pictured in Table 11. On the left side, there are three boxes capturing the three controversy types. In the middle are three boxes representing the three political systems in which blame games were studied in detail. The three controversy boxes and the three political system boxes stand for the six explanatory variables encompassed in the theoretical framework.2 The political system boxes are situated in the middle to express the idea that a controversy is managed or processed by a political system before it leads to specific consequences.

Figure 3 Causal diagram of the typological theory

The causal diagram reveals that the shape of the political system mediates the relationship between public feedback and blame game consequences. All of the controversy types that pass through the UK political system result in blame games with limited consequences. This means that the UK political system stalls public feedback, even in cases where the latter is strong (as the CSA case suggests). The UK political system seems like a tube that remains clogged, even if filled with considerable public feedback. The main reason for this outcome is the very strong blame barriers that the UK political system provides to incumbents. Restrictive conventions of resignation, frequent ministerial reshufflings, and generally low government involvement make it almost impossible for opponents to get hold of political incumbents. The comfortable blame protection resulting from these barriers makes reputational consequences unlikely and reduces incumbents’ incentives to quickly and boldly address a policy controversy. These observations suggest that the UK political system is rather impervious to public feedback during blame games. Even if the majority of the public sees a need for consequences, it is unlikely that consequences will come about during blame games due to the system’s particular configuration of the political interaction structure, accountability structures, and institutional policy characteristics. This finding is quite at odds with the widely held high esteem for Britain’s political debate culture. Debates in the UK political system may be witty and sharp, but, at least with regard to policy controversies, they often only produce hot air.

The German political system gives the opposite ‘treatment’ to policy controversies during blame games. In the sample, all controversy types, irrespective of whether they exhibited strong or rather weak public feedback, led to blame games with extensive consequences. This implies that in the German political system, public feedback can be amplified through the interactions of blame game actors. Even in cases where the public watches a blame game rather indifferently and does not show too much interest in its consequences, the combatants are likely to really struggle with each other. The main reason for this surprising outcome is the strong ‘executive focus’ in German blame games. The German political system provides opponents with ample opportunities to pressure incumbents to address a policy controversy. The extensive conventions of resignation and the opportunity to grill incumbents before an inquiry commission allows opponents to create the impression of an ‘entangled’ executive, even in controversies that only attract weak feedback. An ‘entangled’ executive is much more likely to suffer reputational damage or give in to policy demands than an executive on top of events. This explains why blame games can exhibit extensive consequences even in cases where public feedback is rather weak. It must be noted, however, that a strong ‘executive focus’ is not a necessary requirement for extensive blame game consequences in the German political system. As the NSU case suggests, strong public feedback can lead to extensive blame game consequences even in cases where blame game interactions predominantly focus on administrative actors and entities. Hence, the German system has at least two mechanisms through which controversies can lead to extensive consequences. We can therefore conclude that the German political system is much more responsive to public feedback during blame games than the UK political system.

The Swiss political system lies somewhere between the UK and German political systems in terms of responsiveness to public feedback. The three controversies processed by the Swiss political system either had limited or extensive consequences. Interestingly, and in line with the patterns revealed for controversies processed by the German political system, strong public feedback is not a necessary requirement for extensive consequences in the Swiss political system (as the TAX case demonstrates). This suggests that public feedback in the Swiss political system can also be amplified through blame game interactions. However, since the consequences qualified as ‘extensive’ in the TAX case have to do with an anchoring effect while immediate policy consequences were thwarted by the parliamentary majority, we can conclude that the Swiss system leads to less feedback amplification than the German political system. Therefore, the strength of public feedback and the extent of blame game consequences are comparatively most congruent in the Swiss political system: Weak public feedback leads to limited consequences (EXPO) and strong public feedback to extensive consequences (CARLOS). Political combatants in the Swiss system are very responsive to the attitudes of their spectators. They are committed to fight if the public wants them to, and they switch into training mode if the public watches the blame game rather indifferently. The main reason for the proportionality between public feedback and blame game consequences lies in opponents’ attempts to forge a ‘pressure majority’ during blame games. Since reputational goals are largely out of reach for opponents in the Swiss system, they concentrate on reaching their policy goals. The stronger the public feedback, the higher the likelihood that opponents succeed in forging a ‘pressure majority’ that will be heard by the collective executive government. Hence the congruence between strength of feedback and extent of consequences. These observations reveal that the Swiss political system is very responsive to public feedback during blame games.

Overall, the typological theory reveals that political systems do not just ‘pass through’ public feedback but give it a decisive twist during blame games. Blame game interactions either stall public feedback (as in the UK political system), amplify it (as in the German political system), or process it in a relatively unchanged manner (as in the Swiss political system). Each political system has its own peculiar way(s) of managing policy controversies. In doing so, some are more responsive to the preferences of the public than others. Put differently, whether or not blame games act as a well-functioning mechanism for transmitting citizen preferences depends on the institutional system in which blame games are played out. The finding that political systems are varyingly responsive to public feedback when they manage policy controversies during blame games has important implications for our understanding of politics and democracy under pressure. These implications will be drawn out in the concluding chapter.