Six months after self-emancipated Crispus Attucks, whom many consider the first casualty of the American Revolution, was killed by British troops in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, a twenty-three-year-old woman, her eight-month-old daughter, and her husband escaped from bondage in Leacock Township, a farming community with over 11,000 acres of arable limestone land that had been settled by emigrants from northern Ireland, two-thirds of whom owned slaves.1 It was a relatively warm Thursday, the 13th of September, and the trio had been planning their evening escape since February, when the young mother had given birth, and dreamed of a time when she and her daughter would be free. She wore “good clothes,” carried “two long gowns, and had new low-heeled shoes.”2 There were no free Blacks in Leacock at the time.

This unnamed fugitive slave and her daughter and husband made plans to escape to Philadelphia. The Philadelphia–Lancaster Old Road would have been a risky route for the trio but was worth the risk if it brought them closer to freedom. The revolutionary spirit was alive in Leacock Township as early as 1770. David Watson, the enslaver of the fugitives, was one of sixty men elected from Lancaster County to represent Leacock Township in defense of American liberty. The fugitives found reinforcement of their belief that they had a right to freedom after overhearing Watson’s conversations that colonists were enslaved and had a right to liberty from Great Britain. For reasons unknown, Watson did not name the escaping trio. Perhaps he surmised that given the small Black population in Leacock Township (348 in 1790), a general description of their clothing would suffice. Their namelessness served as an erasure of their identity. Yet these revolutionary abolitionists provide a searing example of the ways in which freedom-seeking women advanced their liberation.3

Enslaved women ran away. Women in bondage were not content, and running away, or flight, was one of the ways in which they registered their protest. Slaveholders lived with this inescapable reality on a consistent basis, and they did everything they could to get their property returned. Posting advertisements in newspapers was the most pervasive method used to secure the return of runaway women. Runaway slave advertisements were a regular feature of print culture throughout the era of slavery. Newspaper advertisements leaned heavily toward the physical, offering detailed information about the facial and bodily features of slaves; their origin and ethnicity; where they may have gone; and rewards for their return. The advertisements also reflected on-the-ground collective transformations of names and ethnic changes and identities. In other words, the fugitive body became a living and moving text of victimization, protest, and personhood.4 As articulated by historian Marisa Fuentes, “fugitivity in this context denotes the experience of enslaved women as fugitives – both hidden from view and in the state of absconding. It also signifies the fragile condition of runaways who came into visibility through runaway advertisements.”5

Enslaved women and girls ran away as soon as they set foot in the Americas. Some escapes were collective; others were individual. While some newly arrived women escaped immediately, others did so within a few weeks of arrival and others escaped months later. On June 16, 1733, fifteen-year-old Juno arrived on the slave ship Speaker in Charleston, South Carolina. She had arrived from Angola along with 316 other enslaved men and women (out of 370; 54 died during the Middle Passage). Two weeks after being sold to a planter from Dorchester, she escaped.6 Similarly, fourteen-year-old Lucia, who arrived on a slave vessel in Savannah, Georgia and whose country marks were evident on each of her cheeks, escaped in 1766.7 Newcomers like Juno and Lucia were likely caught in the act of escaping days later. Despite the pervasiveness of the escapes, very little documentation exists about the personal experiences of women who attempted to flee.

Running from Bondage seeks to lift the veil on freedom-seeking women during the Age of Revolution. Although it is based on scores of cases in which enslaved women absconded or attempted to flee bondage, Running from Bondage neither attempts to relate all documented instances of fugitivity nor is it about all enslaved women in the British North American colonies. The individuals studied here share one key characteristic: they attempted to flee bondage. I argue that enslaved women’s desire for freedom for themselves and their children propelled them to flee slavery during the Revolutionary War, a time when lack of oversight, and opportunity due to the presence of British troops, created spaces for them to invoke the same philosophical arguments of liberty that White revolutionaries made in their own fierce struggle against oppression. The desire for freedom did not originate with the American Revolution. However, the Revolution certainly amplified the quest for liberty. At stake in this discussion of fugitive women is demonstrating that Black women’s resistance in the form of truancy and escape were central components of abolitionism during the Revolutionary Era. Thousands of women of diverse circumstances escaped bondage despite their status as mothers and wives. In fact, motherhood, freedom, love, and family propelled Black women to escape bondage during the Revolutionary Era, a time when, as historian Matthew Spooner argues, the chaos of war made women’s flight possible due to the breakdown of oversight and colonial authority.8 The war produced chaos that preoccupied enslavers and diverted attention away from the daily full-time control of slaves. There were in fact two wars being waged: a political revolution for independence from Great Britain and a social revolution for emancipation and equality in which Black women played an active role. I therefore challenge Black women’s lack of representation in studies of Revolutionary America and the ways in which Black women enter history. By excavating the story of fugitive enslaved women, Black women’s integral role in the eighteenth-century abolitionist movement is manifest.

The boundaries of slavery and enslaved women’s manipulation of space continue to generate interest. Enslaved women challenged enslavers’ control of their movements through everyday acts of resistance such as truancy and through flight. Fugitive women pursued alternative physical environments in what historian Stephanie Camp terms a “rival geography, alternative ways of knowing and using plantation and southern [and northern] space that conflicted with [enslavers’] ideals and demands.”9 I have adapted the term “rival geography” to refer to the movement of bodies, objects, and information away from plantations and the spaces of enslavers. This rival geography threatened the system of slavery and provided fugitive women autonomous spaces to resist enslavers’ efforts to control their bodies and contain their movements. Containment, a principle of restraint, existed on farms, plantations, and areas controlled by enslavers. This geography of containment was elastic for enslaved women during the Revolutionary Era when more opportunities to leave farms, plantations, and enslavers’ homes existed.10 Running away was a strategic act and represented a central expression of human agency. Flight served as a method of fighting against an oppressive system.11

To understand women’s lives in, and resistance to, slavery requires examining their efforts to escape bondage, and symbolically how what they wore and carried with them in the process of absconding were political acts that challenged enslavers’ powers. Political acts of resistance, such as flight, and women’s thoughts about resistance are in constant dialogue. Although the flight of enslaved women was one of institutional invisibility in that there was no formal organization, no leaders, no manifestos, and no name, their escape constituted a revolutionary social movement in which fugitive women made their political presence felt. In fact, fugitive women displayed a radical consciousness that challenged the prevailing belief that enslaved women could not gain their freedom through subversive actions. The wars that enslaved women waged during the American Revolution grounded the Black radical politics that informed their postwar struggles.

As a consequence of slave flight, many colonies passed laws to control the movement of enslaved women and men. Between 1748 and 1785 Virginia, for example, passed laws prohibiting and punishing “outlying” and “outlawed” activity. In 1748, Virginia distinguished between outlying runaways and outlawed escapees by making truancy (or outlying runaways) a capital offense.12 In Williamsburg, Virginia, Rachel, who was “big with child,” had experience with both truancy and escape. In November 1771, she fled from bondage to ensure that her child would be born free.13 Similarly, eighteen-year-old Lydia ran away twice, seeking to reach Williamsburg.14 The movements of Rachel and Lydia away from plantation spaces illustrates the creation of a rival geography in which both women moved through southern spaces to attain freedom. Through flight, they created spaces for private and public expressions of freedom.

Colonial Black resistance in the form of self-emancipation was a form of abolitionism. In “mining the forgotten” women who appear in runaway slave advertisements, historians recover Black resistance. Historian Manisha Sinha’s study of abolitionism, The Slave’s Cause, has advanced new perspectives on Black abolitionism that challenge the idea that White philanthropy and free labor advocates were responsible for the abolitionist movement. Key to her book is the argument that “slave resistance, not bourgeois liberalism, lay at the heart of the abolitionist movement.” Sinha revives the early perspectives advanced by scholars such as C.L.R. James and Benjamin Quarles, who viewed runaway slaves as the “self-expressive presence [without whom] antislavery would have been a sentiment only.”15

An Understudied Phenomenon

This book builds on the histories of how the American Revolution impacted slavery and freedom by highlighting the experiences of enslaved and fugitive women. Although numerous books have been devoted to the Revolutionary Era and its impact on slavery, none focus singularly on fugitivity by enslaved women in the thirteen colonies and their links with the wider Atlantic world. The first historian to seriously study the issue of slave resistance during the Revolutionary Era was Herbert Aptheker in American Negro Slave Revolts (1943). Aptheker’s research was groundbreaking because it illuminated the colonists’ fear that the British would wage war under an anti-slavery banner that would lead to “20,000 slaves” running to the British lines within a few weeks.16 Benjamin Quarles in his classic study The Negro in the American Revolution (1961) makes clear the contradiction of the colonists’ fight for their liberty from Great Britain while maintaining the institution of slavery when he states, “In the Revolutionary War the American Negro … personified the goal of that freedom in whose name that struggle was waged.”17 Quarles argued further that the American Revolution constituted the first large-scale slave rebellion. Post-Quarles, Gerald Mullin’s research on Virginia for the period 1736–1801 uncovered 1,280 runaways, or an average of 19.7 per year, with the majority occurring during the Revolutionary War. Philip Morgan in his analysis of South Carolina from 1732–1782 collected advertisements describing the flight of 3,558 slaves, or 69.8 per year. Not only did these historians use all extant newspapers, but the slave populations of Virginia and South Carolina were comparatively large, with Virginia’s slave population totaling 188,000 in 1770 and South Carolina’s slave population totaling 57,000 by 1760.18

Given America’s Revolutionary heritage it is not surprising that slavery has long captured the collective historical consciousness of the nation. Students and faculty alike continue to ponder the imponderable: the relationship between slavery and the kinds of freedom enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Historians Ira Berlin, Ronald Hoffman, David Brion Davis, Sylvia Frey, Woody Holton, Gerald Horne, Gary B. Nash, Simon Schama, and Cassandra Pybus have examined the transformations wrought by the American Revolution on the institution of slavery.19 In each of these studies, the agency of enslaved women and men is paramount. In his thought-provoking essay “On Agency,” historian Walter Johnson contends that historians’ over-emphasis on agency, which refers to the self-directed actions of slaves, minimizes the brutality that enslaved people faced. In addressing the agency of enslaved women during the Revolutionary Era, in this study I present fugitive women as the architects of their own actions who challenged their enslavers’ power and perceptions. Hence, I do not “give” agency to enslaved women, but simply recognize the agency that they created themselves. Recognizing how power shaped agency and vice versa, this study balances agency with manifestations of freedom.20

The most salient examination of Black agency in the Age of Revolution is Sylvia Frey’s Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Frey argues that the Revolutionary War in America’s Southern colonies, rather than being merely a struggle between colonists and Englishmen, was a three-sided affair between Black slaves, White Americans, and the British, with each faction playing an independent and important role. She also concludes that republican political theory and Christian religious belief played huge, crucial roles in the thinking of African Americans as they struggled against slavery during this time. Frey notes that when the Revolution began, many slaves in the South took advantage of the situation to declare their freedom. They appealed to the British to guarantee their liberty, even though they realized that Britain was itself deeply involved in the slave trade, and large numbers of slaves fled to the “protection” of British armies. Also, some of them escaped to remote places to form maroon colonies, while others fomented full-scale rebellion. They continued into the next decades to resist slavery in the name of the liberation rhetoric of the Revolution and the individual dignity taught by Christianity. Taking Frey’s argument further, Woody Holton’s Forced Founders argues that slaves engaged in insurgency long before Lord Dunmore’s official offer of freedom and that their actions, along with the fear of general emancipation, united free Virginians in advocating for independence from Great Britain.

In his study, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution, Gary Nash contends that one-third of all fugitives were women, a far greater number than in previous patterns. Who were these women? What obstacles did they face in attempting to flee bondage? Were they successful? The voices of enslaved women escaping bondage during the eighteenth century are silent, with few exceptions. As Marisa Fuentes has argued, these silences in the archive of bondwomen in slave societies bury the narratives of the most subaltern.21 The overall invisibility of fugitive women seems to be due in part to the fact that women in general are often overlooked in studies about the enslaved population. Such male-specific analyses do not correspond to the reality, whether in North America or in the rest of the hemisphere.

Fugitivity and Links with the Atlantic World

Slavery, as Dale Tomich argues, was one “of the strands that wove the histories of Europe, Africa, and the Americas, creating at once a new unity and a profound and unprecedented divergence in the paths of historical development of these regions and their people.”22 Slavery was foundational to European expansion projects, and its growth became inseparable from inter-imperial competition that turned the Atlantic into a theater of war in the eighteenth century. With this process came opportunities for free and enslaved African populations who in most cases were clearly aware of, and central to, the political conflicts of the age. With increasing frequency scholars have recognized the impact that the Age of Revolution had on slavery. Latin American historians from Gilberto Freyre to Frank Tannenbaum to Herbert S. Klein and Ana Lucia Araujo have studied slavery in Spanish and Portuguese colonies, as have scholars of the Caribbean islands. Barbara Bush has commented of West Indian slave women that “popular stereotypes have portrayed them as passive and down-trodden work horses who did little to advance the struggle of freedom.” The “peculiar burdens” of their sex allegedly precluded any positive contribution to slave resistance.23

However, enslaved women in the British Caribbean exasperated their enslavers in countless ways. They shirked work, damaged crops, dissembled, and feigned illness. They also ran away. Enslaved women ran away for a variety of reasons. They sought to put pressure on their enslavers to sell them or improve conditions. They also ran away to visit kin or friends. Many attempted to merge into the free Black and urban communities, where they often found employment. Historian Gad Heuman suggests that runaways were less concerned about freedom than with preserving some sort of autonomy within slavery itself, which raises the question of the degree to which enslaved women could control and affect aspects of their enslavers’ world.24

Young men without family ties predominated among runaways in the Caribbean; however, according to historian Barbara Bush, 40 percent of runaways in the Caribbean were women. Women took their children with them far more frequently than did men. However, if caught, both mothers and children were forced to wear collars, and running away with children meant that the women were more likely to be caught.25 French historian Arlette Gautier suggests that women may not have had less desire to run away, simply less opportunity. Advertisements in the Jamaican Mercury and Kingston Weekly Advertiser (the Royal Gazette after 1790) provide important insights about women’s family connections and their status and value. A number of slave women ran away with their children or other close relatives, an indication of strong familial bonds. Other runaways were suspected of having fled to join spouses or other kin from whom they had been separated, and often the advertisers alleged that their runaways were being harbored by kin or friends in distant parts of Jamaica. Thus, a significant number of women, African and creole, were among the lists of runaways.26

Slave imports from the Caribbean to the North American mainland increased during the eighteenth century. According to David Eltis’s slave trade database, nearly 140,000 Africans were imported from Africa as well as the Caribbean between 1711 and 1740.27 What is true about the Atlantic during this period is that absolute differences or actual boundaries were not real since we are talking about a deeply interconnected world. Illustrative of this is Margaret Grant, a fugitive slave from Baltimore, Maryland who had also experienced slavery in Barbados, Antigua, and the Grenadines and who escaped slavery at least twice.28

Revolutionary Women

During the American Revolution, one-third of runaways were women and more than half fled in groups rather than alone. By contrast, prior to the Revolution, nearly 87 percent of colonial runaways were male, and about two-thirds fled alone. Roughly 25 percent fled in family groups consisting of husbands, wives, and young children.29 Enslaved women pursued multiple avenues to gain freedom during the Revolutionary Era. Some, like forty-year-old Sarah of Pennsylvania, made plans to reach New York City on the eve of the Revolution on October 24, 1769, where ships headed for other northern ports docked. Others, like twenty-three-year-old Bellow, who was born in Barbados, sought to find refuge away from her enslaver’s home on Broad Street in New York City on April 28, 1770. Others, like “Free Fanny,” claimed freedom by running away on Christmas Day 1770 from her enslaver’s estate in Essex, Virginia.30 To migrate to another city or colony may seem to have been an improbable proposition for women in bondage. Going to town or to another colony implied that they had knowledge of the geography and topography of the area.31 The enslavers of eighteen-year-old Lydia (mentioned earlier) remarked that she had traveled the road to Williamsburg several times and was familiar with the route since she had attempted escape on more than one occasion. The escape of many enslaved women was polycentric (having more than one center) in that they attempted to flee more than once.

Southern cities and Northern colonies were open spaces for freedom-seeking women during the Revolutionary Era. They could find refuge with the British, escape to Black enclaves in the cities and pass as free women, as well as find refuge with Native Americans. In some cases, women found refuge in the woods and swamps because “there was no other place of concealment and freedom for them.”32 They experienced what Damian Pargas describes as an “informal freedom,” spaces within slaveholding regions where enslaved people attempted to escape by blending in with the free Black population.33 As they experienced this “informal freedom,” women truants in rural areas embraced the ecology. Women had knowledge of the fauna and flora, the animals and plants they would find, and what vegetation they should not eat. They also had familiarity with changes in the weather and had family and friends nearby.

In Virginia, 12,000 runaway slaves were with Lord Cornwallis’s army by the middle of June 1781. In total, it has been estimated that Virginia lost 30,000 slaves during the Revolutionary War.34 Virginia’s fugitive slaves did more than serve soldiers as porters and body servants. They contributed substantially to Cornwallis’s new style of warfare. Cornwallis encouraged bondwomen and bondmen to leave their enslavers, thus threatening Virginia with complete economic ruin. Virginia’s fugitives also served Cornwallis in a more deliberate fashion. Runaways acted as spies and guides for the British. They frequently showed British soldiers where fleeing enslavers had hidden their valuables and livestock. In fact, African Americans delivered so many horses to Cornwallis that General Lafayette exclaimed, “Nothing but a treaty of alliance with the negroes can find out dragoon horses, and it is by those means the enemy have got a formidable cavalry.”35 The militia was Virginia’s last remaining line of defense. The strength and speed of British forces terrified Virginia’s citizen-soldiers. Militiamen were reluctant to take up arms lest they provoke the British into destroying their homes. The militiamen also feared leaving their families alone with their slaves. “There were … forcible reasons which detained the militia at home,” explained Edmund Randolph, who had been a Virginia delegate to Congress. “The helpless wives and children were at the mercy not only of the males among the slaves but of the very [slave] women, who could handle deadly weapons.”36

The frequency of flight by groups of slaves in Virginia is noteworthy and is indicative of the complexities of escape. A total of 329 acts of collective escape appear in runaway advertisements from the 1730s to 1790.37 (A group is defined by Aptheker as three or more slaves.) In many cases during the Revolutionary War, fugitive women ran away with their husbands and children. In July 1778, Mary Burwell placed an advertisement for the return of Venus, Zeny, Nelly, and Jack, who escaped slavery in Prince William County and were seen in Isle of Wight County, Virginia. Jack and Venus were husband and wife and Zeny was the mother of Nelly. The group had plans to reach Williamsburg, which served as a departure point for many fugitives who intended to walk the four miles to Burwell’s Ferry on the James River. Fugitive women who survived the war, perhaps four of every six, confronted several obstacles to freedom after the war. Among the obstacles was the pressure placed on the British by American diplomats to return fugitive slaves to their enslavers.38

Urban and rural enslaved women, literate and illiterate, were swept up by the force of revolutionary ideology. In a period of history when written communication was still hindered by undependable mail service and a paucity of printers and publishers, more people probably heard the news of Lexington and Concord from riders on horseback than read about it in newspapers. Black women had the means to maintain a vital oral tradition through the “common wind,” the tradition of carrying oral communication that Africans retained in America. Table talk listened to by domestic slaves or conversations overheard by slave attendants was quickly transmitted to other slaves and disseminated to other quarters and plantations. Two of Georgia’s delegates to the Continental Congress, Archibald Bullock and John Houston, confided to John Adams that the slave network could carry news “several hundreds of miles in a week or fortnight.”39

The flight of enslaved women indicates that they did follow the progress of the war, and fully appreciated its implications for their own lives. Foremost among the implications of the war was American freedom. When the British launched their southern strategy in Georgia and South Carolina in 1778, women escaped following the arrival of British forces. Among these fugitives were Renah, Sophia, and Hester and her son Bob.40 Their escape, like that of many others, found its strategy and meaning in patterns of African resistance where self-reliance and survival strategies prevailed. As in the West African societies from which they were transported, kinship relations informed the social, religious, and political foundation of slave communities. Kinship relations, both fictive and non-fictive, were crucial to the achievement of short-term and long-term political objectives which included flight.41

General Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation in 1779 offering freedom to slaves willing to help the British led to the escape of scores of women. About two-fifths of those who escaped following the proclamation were women. Many of the women brought young children with them or had children while under British protection. Children born in British camps were free. Once under British protection women served as cooks, servants, laundresses, or did general labor.42 Although the possibilities for maroon types of resistance were limited in the British American colonies, the expanse of unsettled frontier and a comparatively large amount of swampland in the South Carolina and Georgia Lowcountry, Florida, Louisiana, and the Great Dismal Swamp offered sanctuary for marronage. Marronage refers to the establishment of fugitive slave communities in the woods, swamps, and mountainous regions of the Americas. Renah, Sophia, Hester, and Bob were believed to be headed to St. Augustine, Florida where the Spanish offered freedom to fugitive slaves and where maroon societies were established.43

In their attempts to rid themselves of chronic runaways through sale, or to retrieve offenders through public notices, eighteenth-century enslavers acknowledged the intelligence, resourcefulness, and boldness of bondwomen. As historian Jacqueline Jones argues, descriptions of enslaved women “belie the conventional stereotypes that became popular during the early nineteenth century which portrayed Black women as obedient, passive, and lacking in imagination or strength.”44 Revolutionary Era runaways included Milly, “a sly subtle Wench, and a great Lyar”; Cicely, “very wicked and full of flattery”; and Hannah, “very insinuating and a notorious thief.”45 Women condemned “as guileful, cunning, proud, and artful often assumed the demeanor of free Blacks, a feat accomplished most often in cities, and with the help of relatives, both slave and free.”46 These examples must be juxtaposed with the experiences of most enslaved women, who made the calculated decision to remain in their enslaver’s household “and thereby provide for loved ones in less dramatic, though often equally surreptitious ways.”47

The extraordinary flight of women during the war years also contributed to a crisis of confidence in the postwar era. The exodus of slaves “engendered by the British invasion and occupation created a severe labor shortage that destroyed the basis of the South’s productive economy and weakened the wealth and power of its richest families.”48 In its postwar recovery effort, planter-merchants sought to rebuild the collapsed economies through the massive importation of African slaves and by enacting repressive slave codes. Planter-merchants also formulated a patriarchal ideology, which drew upon scripture and revolutionary ideology to proclaim that the social order was authorized and decreed by God, nature, and reason. Enslaved women found ways to challenge this patriarchal ideology in the postwar period through various stratagems, which included flight.

The story presented in these pages is unique. It examines the ways in which women’s escape undergirded notions of womanhood, motherhood, and freedom. The war bolstered the independence of fugitive Black women, gave them increased access to their families with whom they fled, and greater autonomy in their day-to-day lives once they reached safe havens. Women ran away during the Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary period to claim their liberty, an act which they viewed as consistent with the ideals enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. Underlying the causes of their flight were efforts to defend their bodies and womanhood against exploitation, as well as to protect their children from the deleterious effects of the institution of slavery.

During the Revolution, women not only ran away with immediate family members, but also in groups without established kinship relations. They correctly perceived that their best chances for freedom resided with a British victory and a disruption of the existing social order. In the north and south, women fled to urban centers, took refuge in British camps, aided the Loyalist cause as spies, cooks, nurses, and performed duties for the British Army Ordnance Corps. In the postwar period, most Black women did not seek freedom in the North, but instead pursued “informal freedoms” in urban cities such as Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans where they defined freedom in terms of family and mobility. In these cities, they relied on networks of acquaintances, marketable skills, clothing, and language skills to assume identities as free women and carve out free spaces for themselves.

Sources and Methodology

This social history of enslaved women during the Revolutionary Era has a wide span; it focuses on the Southern and Middle colonies where British forces battled with colonists, but also examines cases from the New England region. This regional approach can vividly retrace the experiences of fugitive women because it conforms to the reality on the ground. The pre-Revolutionary period from 1770 to 1775 witnessed disruptions in the institution of slavery as enslaved women took advantage of every opportunity to escape bondage. Lord Dunmore’s 1775 Proclamation and Sir Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation of 1779 offering freedom to fugitives who joined the British army further disrupted the plantation economy as enslaved women fled plantations to follow their partners, husbands, and sons.

The temporal scope of Running from Bondage is the pre-Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary period to 1800; and its organization is chronological and thematic – emphasizing the various routes to freedom taken by fugitive women – because it focuses on fugitive women’s individual and communal experience. Their world is at the center of analysis. Two themes are central to this study: the creation of a rival geography through fugitivity and fugitivity as a revolutionary act of resistance. Although the evidence is fragmented, the experiences of fugitive women are far from unknowable. While the firsthand accounts of runaways who settled in the North and Canada comprise an extensive body of abolitionist literature during the antebellum period, the accounts of runaways during the Colonial period are limited to colonial newspaper advertisements for runaways. In reading newspaper advertisements for runaways, the silences within the advertisements require that I imagine the varied meanings and possibilities that are inherent in these silences. I therefore find it useful to read against the grain in order to augment the fragmented archives.

Runaways were by definition a select group. Certain segments of the Black population – the young, mulattos, African, West Indian – are overrepresented. The ultimate value of runaway advertisements lies chiefly in what they can tell us about the life stories of individual slaves. Each advertisement “describes part of the story of a real person, not an abstraction. When further research in other sources is undertaken, these human stories can be fleshed out as real human beings begin to emerge from the records.”49 There are limits to the utility of the advertisements in understanding the lives of enslaved women. We do not know the ultimate fate of the majority of the individuals named in the advertisements. Enslavers did not place advertisements for every runaway since many were captured quickly. But given these limitations, the runaway and captured advertisements still offer a remarkable amount of information about individual human beings caught in a horrific system of bondage. And when augmented with other sources, such as petitions, letters, county books, parish records, official correspondence, diaries, and plantation records, the advertisements can begin to restore human dignity to a group of persons who have long been denied their dignity.50

Newspaper advertisements map fugitive women’s geography, detail individual stories, and go to the very reason for attempted escape. A number of other sources help reconstruct fugitive women’s stories in their own voices and the voices of their relatives and friends. Trial records are an important source of first-person accounts. I concur with historian Sylviane Diouf that such documents must be handled with caution, as defendants and prosecutors may have been inclined to distort, lie, and minimize or overstate facts and claims. The threat and actual use of torture, sometimes bluntly acknowledged by prosecutors, must add a layer of circumspection to the person’s account. But invaluable information can be gathered by paying attention to details.51

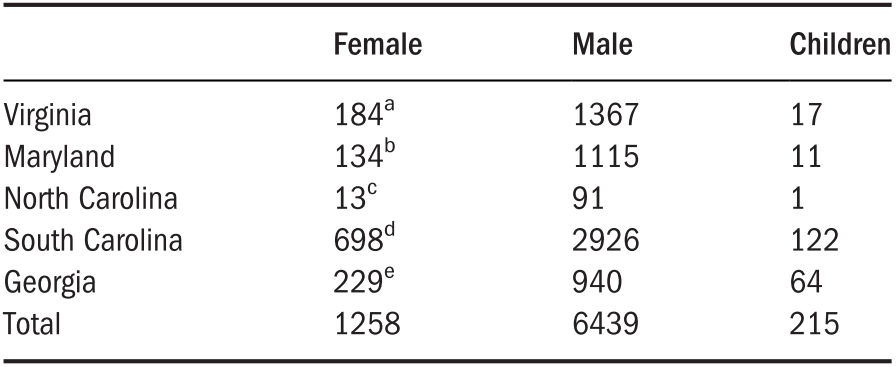

The four documentary volumes of Lathan Windley’s Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790 are an invaluable resource. Volume one, which details Virginia and North Carolina escapees, includes for Virginia a total of 1,568 fugitives, of whom 184 were women (six are stated to be pregnant). Seventeen are noted as being children below the age of ten; the remaining 1,367 are men. Included in these totals are one woman described as a free Negro, one Indian woman slave, one Indian man slave, and seven White indentured servants. In the remainder of the first volume dealing with North Carolina (where the population was sparse and extant newspapers relatively few) there are a total of 105 fugitives, one of whom was a child, thirteen of whom were women (one described as pregnant), and ninety-one of whom were men.52

Volumes two and three are devoted to Maryland and South Carolina, respectively. The number of fugitives being sought by advertisements in Maryland totaled 1,290, of which 134 were Black women (four described as pregnant), eleven were children, and thirty were White indentured servants. A total of 1,115 Black male runaways were advertised in the state of Maryland. The number of fugitives sought in South Carolina totaled 3,746, of which 698 were women (fourteen listed as pregnant) and 122 were children. A total of 2,926 Black men were advertised as fugitive slaves in South Carolina from 1732 to 1790.53

Volume four reprints slave advertisements from the few extant newspapers in Georgia, where slavery was illegal until 1750. From the first available advertisement in 1763 through 1790 there were a total of 1,233 fugitives. Of these, 229 were women (one was pregnant and one was Indian) and 64 were children, including eight specifically listed as infants. A total of 940 were Black men. The overall totals for the five areas through 1790 are: women, 1,258; children (under ten), 215; men, 6,439. (See Table 0.1.) Altogether, a total of 7,942 women, men, and children were advertised as fugitives. These data by no means reflect the totality of slave flight, as newspaper files are not complete and enslavers tended to place ads only when fugitives were missing for many days or even months. Also, newspapers were published in the few urban centers of the period so that plantations or homes near such centers were the main sources of advertisements.54

| Female | Male | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia | 184a | 1367 | 17 |

| Maryland | 134b | 1115 | 11 |

| North Carolina | 13c | 91 | 1 |

| South Carolina | 698d | 2926 | 122 |

| Georgia | 229e | 940 | 64 |

| Total | 1258 | 6439 | 215 |

a. Six women were pregnant.

b. Four women were pregnant.

c. One woman was pregnant.

d. Fourteen women were pregnant.

e. One woman was pregnant.

Antebellum memoirs and interviews of former runaways are also a rich source of information. Ona Judge, a fugitive slave of George Washington, told her story to abolitionist Thomas H. Archibald forty-nine years after her escape. Her story appeared in the Granite Freeman in May 1845. A second interview with Ona Judge appeared in the Liberator, the nation’s most powerful abolitionist newspaper, in 1847. Judge’s interviews, according to Erica Armstrong Dunbar, are quite possibly the only existing recorded narrative of an eighteenth-century fugitive.55

***

In fleshing out enslaved women’s fight for freedom, this book seeks to answer several key questions. How did Black women advance their own liberation during the Revolutionary Era? What regional variations and similarities existed in the flight of enslaved women? How did fugitive women engage with maroon societies? How does Black women’s flight fit into the larger narrative of slave resistance? To emphasize the centrality of enslaved women who escaped bondage during and after the American Revolution, Running from Bondage directly engages archival silences within historical primary sources. Each chapter of this book begins with an event that foregrounds enslaved women’s experiences with flight in what becomes an extended examination of fugitivity and the milieu of the Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary period. To uncover, re-create, and analyze the world of fugitive enslaved women, this book consists of five thematic chapters.

Chapter 1 provides an analysis of the status and position of enslaved women during the eighteenth century. The daily and seasonal work of enslaved women determined the boundaries within which women had to resist their bondage and their opportunities to do so. This chapter provides a broad understanding of enslaved women’s labor in the southern and northern colonies as a basis from which to further examine enslaved women’s fugitivity in subsequent chapters. This chapter demonstrates the diversity in enslaved women’s experiences during the eighteenth century and the gendered resistance strategies they pursued to contest their bondage.

Chapter 2 is an examination of the pre-Revolutionary period. This chapter examines the flight of a mulatto woman named Margaret Grant who escaped slavery in Baltimore, Maryland in 1770 and 1773. This chapter examines the meaning of freedom through a delineation of acts of self-emancipation and places the story of Margaret in the context of the wider Atlantic world. Ideas about freedom are in many ways fruitful to investigate when analyzing the experiences of enslaved women. Bondwomen expressed their thoughts about freedom in private and public discourse throughout the era of slavery. Their involvement in conspiracies and acts of resistance such as running away is evidence of their willingness to fight for freedom no matter what the outcome.

Chapter 3 examines the ideas of the American Revolution and places fugitive slave women at the center of analysis. The impact of Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation are examined. From plantations, women escaped to cities and towns, North and South; they fled poverty and malevolence. Following the pronouncement of the Philipsburg Proclamation, 40 percent of runaways were women. There were regional variations and similarities in the flight of enslaved women. In the Southern colonies, enslaved women pursued refuge in Spanish Florida and with British troops during the Southern Campaign; in the Chesapeake colonies, enslaved women fled to Pennsylvania and other northern destinations, often seeking refuge with British troops in the process of escaping; in the Northern and New England colonies, fugitive women sought refuge with the British during the war’s early campaigns, but also endeavored to reach cities such as New York. In each of these regions, fugitive women also endeavored to pass as free women in urban spaces. Indeed, throughout the Revolutionary Era, enslaved women advanced their liberation through flight.

Chapter 4 examines the obstacles enslaved women faced in escaping bondage in post-Revolutionary America. The case of Elizabeth Freeman, an enslaved Black woman in Massachusetts who sued for her freedom, captures the tenacity of Black women, who not only resisted with their feet, but also used the courts to gain their freedom. By highlighting the case of Ona Judge, the fugitive slave of George and Martha Washington, this chapter brings to the fore successful escapes in which enslaved women overcame formidable obstacles to freedom.

Chapter 5 examines the gendered dimensions of maroon communities in America and the wider Atlantic world. Maroons were fugitives from slavery who established independent communities in swamps, deep woods, mountains, isolated islands, and other wilderness sanctuaries. Fugitive women joined maroon societies with their husbands and other family members. Runaways were a constant source of anxiety and fear. In the Caribbean and places such as Georgia, Florida, and the Gulf Coast and along the perimeter of the Virginia and North Carolina border in an area known as the Great Dismal Swamp, they were successful in establishing maroon societies. Such societies maintained their cohesiveness for many years. Given that the woods and swamps were spaces where the enslaved could exercise more autonomy than the fields and other open spaces on the plantation, fugitive women had more freedom in these spaces.

The enslaved women who escaped or attempted to escape bondage registered their hatred for chattel slavery and their desire for liberty – a desire so great they willingly braved danger to realize it. During the war, many chose death instead of returning to bondage. The goal of this study is to present an American Revolution that is inclusive of Black women. Running from Bondage broadens and complicates how we study and teach this momentous event, one that emphasizes the chances taken by the “Black founding mothers” and the important contributions of women like Margaret Grant to the cause of liberty. Wherever freedom is cherished, their struggle and sacrifice should be remembered.