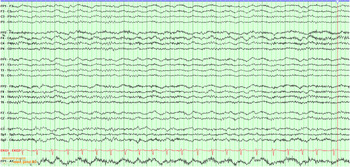

Here, we report a case of a 36-year-old man with antibody-confirmed N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis who was admitted at age 15 with a similar presentation, representing a delay to first relapse of 21 years. Our patient presented at age 36 with a 10-day history of progressive word-finding difficulties and paranoid ideation, preceded by URTI symptoms. On admission examination, he was bradyphrenic with expressive aphasia, short-term memory impairment and executive dysfunction. He had left beating gaze-evoked nystagmus and orofacial dyskinesias, but no other cranial nerve, sensorimotor or cerebellar abnormalities. Empiric ceftriaxone and acyclovir were started. A lumbar puncture showed elevated protein (1395 mg/L) and WBC (56 × 10^6 cells/L – 82% neutrophils). Viral PCR was negative. Contrast MRI head was unremarkable. EEG showed changes suggestive of extreme delta brush pattern (Figure 1). He progressed to frank psychosis and florid agitation by post-admission day 2, and autonomic disturbance with altered temperature regulation and sinus tachycardia by day 7. IVIG (2 g/kg) was started at day 5, followed by a 5-day course of IV methylprednisolone at day 10 given no early response to IVIG. IVIG was initiated before steroids due to concern about exacerbating psychosis. NMDA receptor antibodies returned strongly positive in the serum and CSF. Neoplastic screen (CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, with testicular ultrasound) was negative. He continued to deteriorate to a non-verbal state by day 14. Due to lack of response to immunotherapy, plasma exchange (PLEX) was performed at day 20, and Rituximab (1 g IV × 2 doses 2 weeks apart) started after PLEX at post-admission day 30. His neurological status improved markedly over 3 weeks following five cycles of PLEX. On discharge at day 50, he had marked improvement with a Montreal Cognitive Assessment score of 25/30. After further active rehabilitation, at 1-year follow-up, he returned to baseline and is working at his previous level of function.

Figure 1: EEG in bipolar montage demonstrating diffuse moderate amplitude frontally predominant 0.5–1 Hz delta activity with superimposed high-amplitude frontally predominant discharges (right more than left) suggestive of “extreme delta brush”. The background consists of moderate amplitude, well-developed 8–9 Hz alpha posterior dominant rhythm. (Sensitivity 7 mA, 60 Hz filter on).

Medical records were reviewed for his presentation at age 15, with a 4-week history of acute confusional state, starting as intermittent memory difficulty and progressed to bizarre behaviour, mutism and psychomotor retardation. Initial examination revealed hypophonia, inappropriate smiling and delusions of reference without cranial nerve, sensorimotor or cerebellar abnormalities. Initial investigations including brain CT scan and routine CSF studies were normal, with negative infectious workup. His first EEG showed a dysrhythmic pattern with left temporal sharp waves in sleep state. Autoimmune antibody testing for inflammatory causes was not performed, as this was not available in 1998. Over the next few weeks, he deteriorated into a non-verbal, catatonic state with hyperthermia. He was treated empirically for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, possibly related to antipsychotics started for his behavioural state. He had two clinical seizures with left hemispheric onset and was treated with phenytoin and phenobarbital. Repeat EEG showed diffuse theta activity with left temporal sharp waves. Extensive workup for vasculitis, rare infections and inborn errors of metabolism was negative. Contrast MRI brain was normal. Skin and right frontal brain biopsy did not show areas of inflammation. Despite this, empiric immunosuppression with pulse IV methylprednisolone for presumed inflammatory CNS disease was started. A week later, he exhibited signs of improvement. His antiepileptic medications were weaned without further seizures. He recovered over the next year, completed high school, a bachelor’s degree and started his own business. Table 1 contrasts his two presentations.

Table 1: Comparison of childhood (presumed autoimmune encephalitis) and adult presentation (definite NMDA-R encephalitis) clinical and laboratory features

NMDA receptor encephalitis is an immune-mediated neurological syndrome presenting with personality change, memory loss and behavioural abnormalities, often progressing to psychosis, seizures, movement disorders, autonomic dysfunction, hypoventilation and coma.Reference Dalmau and Graus1 An underlying neoplasm is detected in approximately 40–60% of patients, the majority of which are ovarian teratomas; the remainder of cases are presumed to be autoimmune.Reference Dalmau and Graus1–Reference Titulaer, McCracken and Gabilondo3 Autoimmune causes of encephalitis are common and early identification of a compatible syndrome, exclusion of infectious causes and application of appropriate immune therapy can significantly improve survival and outcome in these patients. In a cohort study of 501 patients, Titulaer et al.Reference Titulaer, McCracken and Gabilondo3 demonstrated 69 relapses in 45 patients at 2 years, defined as “the new onset or worsening of symptoms occurring after at least 2 months of improvement or stabilisation.” 23/69 relapses were comparable or more severe than previous episodes. Relapse rate was higher in patients without a tumour. This suggests that a period of monitoring for relapse may be required. The long period of quiescence in our case is unusual for NMDA receptor encephalitis. Time to first relapse varies in the literature, with a median delay of 18–24 monthsReference Dalmau, Lancaster, Martinez-Hernandez, Rosenfeld and Balice-Gordon2,Reference Gabilondo, Saiz and Galan4 ; in one patient, a longer delay of up to 13 years was reported.Reference Gabilondo, Saiz and Galan4 Relapse risk was higher in patients without a tumour and those who did not receive immune therapy at the onset of disease. Dalmau et al.Reference Dalmau and Graus1 describe two main emerging pathophysiological mechanisms by which antibodies to central nervous system proteins may arise.Reference Dalmau and Graus1 The first mechanism involves leakage of CNS antigens across the blood–brain barrier during episodes of viral encephalitis. The second mechanism is by expression of CNS antigens on tumour cells in the periphery. It has been suggested that relapses may indicate recurrence of the initial tumour or presence of an undiagnosed malignancy. In our patient, HSV was not isolated in CSF during either presentation nor was a tumour found. It has been shown that serum antibody titres do not correlate with disease relapse and are not useful for monitoring, but that CSF antibody titres do correlate with disease activity.Reference Gresa-Arribas, Titulaer and Torrents5 However, serial CSF analysis is not a practical method of monitoring for relapse over time owing to its invasiveness. At this time, monitoring for relapse remains clinical. Patients and family members should also be educated about the signs and symptoms of relapse that should prompt re-evaluation by a neurologist.

In conclusion, NMDA receptor encephalitis is a treatable condition if recognised early. Factors associated with long delays to relapse are unknown. Development of a registry of NMDAR patients for long-term follow-up, now that the antibody is well characterised and commonly tested, may more precisely clarify the natural history and outcomes of this condition.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Authorship

S.A., M.A., J.L. and C.U. drafted the manuscript and revised the content. M.J. reviewed, critiqued and edited the manuscript.