Introduction

In November 1967, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) mounted a “Great Demonstration” in London against the British government’s 1967 White Paper, Fuel Policy, and the forecasts of further industry closures.Footnote 1 The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Man Alive program captured the demonstrators’ mood: “[T]he purpose of the march was to win a reprieve from … the men who’ve never handled … coal in their lives other than to throw it on the fire.”Footnote 2 At Westminster’s Central Hall, NUM General Secretary Will Paynter described colliery closures “like a disaster” (raising the specter that always haunted mining, with added poignancy a year after the Aberfan disaster that claimed the lives of 116 children and twenty-eight adults in the Welsh mining community): “It hurts. There’s an emotional reaction as if it were a death in the family. And this sort of sentiment has to be appreciated.”Footnote 3 The state-owned National Coal Board’s (NCB) Coal News, covering the events, juxtaposed the wealth on show in London’s west end with the impacts of coal industry closures.Footnote 4 Through this national protest and the rhetoric used by Paynter and others, the NUM sought to give voice to the groundswell of anger in the coalfields demanding an acknowledgment of the damage being wrought, to pressurize the government, and to elicit public sympathy. NCB and BBC coverage demonstrated heartfelt sympathy for the plight of mining communities. Both echoed the tactics of collective action against the Means Test in the 1930s, which had been lodged in labor movement memory.Footnote 5 This manifestation resounded with mining communities’ outrage at the assault on settled norms and obligations practices of the moral economy of nationalized coal.Footnote 6 The NUM’s Great Demonstration and miners’ invasion of the floor of the 1968 conference of the governing Labour Party in Blackpool, marked a watershedFootnote 7; in the preceding decade, protests had been confined to those coalfields most affected by closures; these actions brought this to the national stage and a wider public audience.

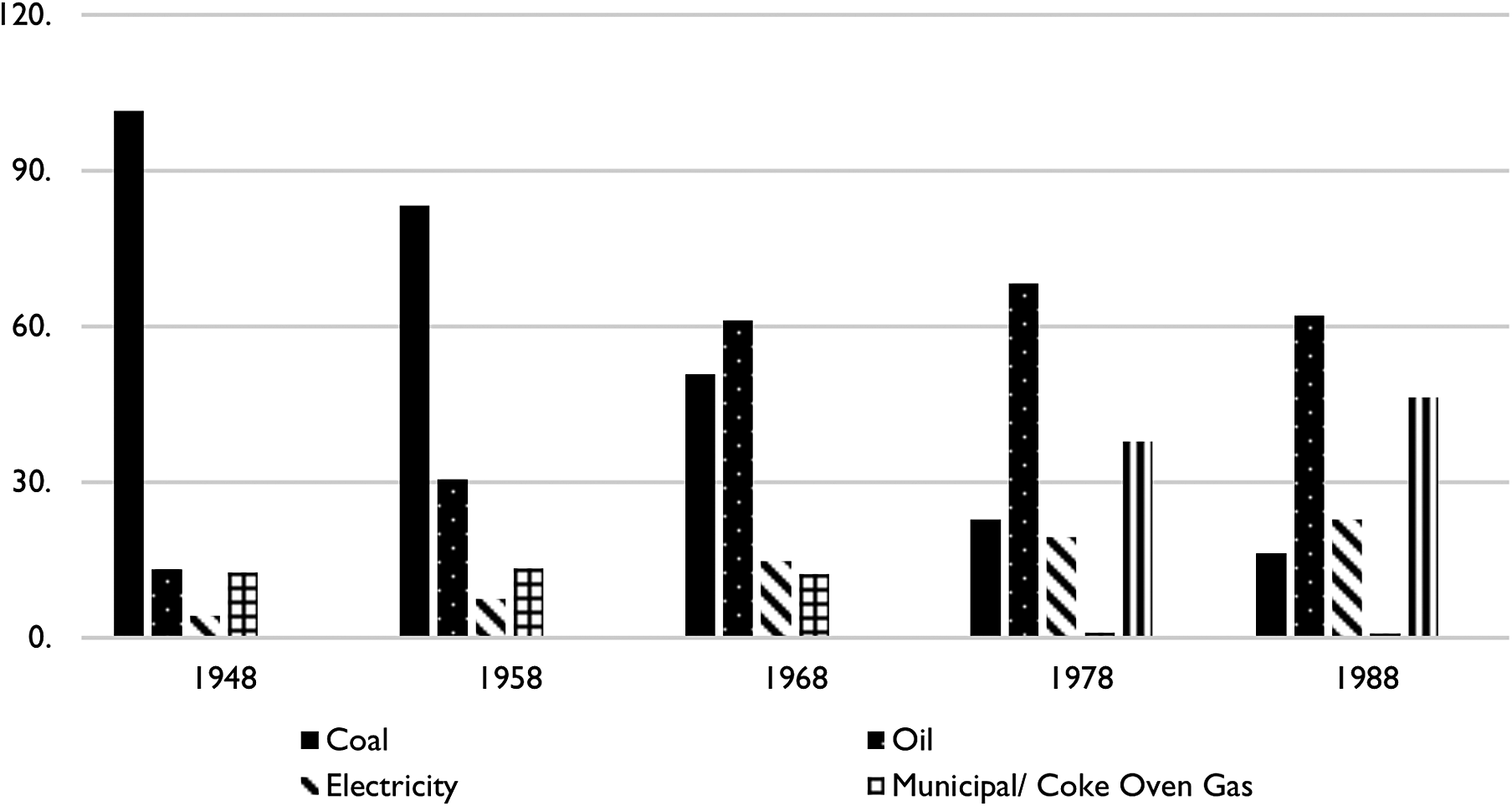

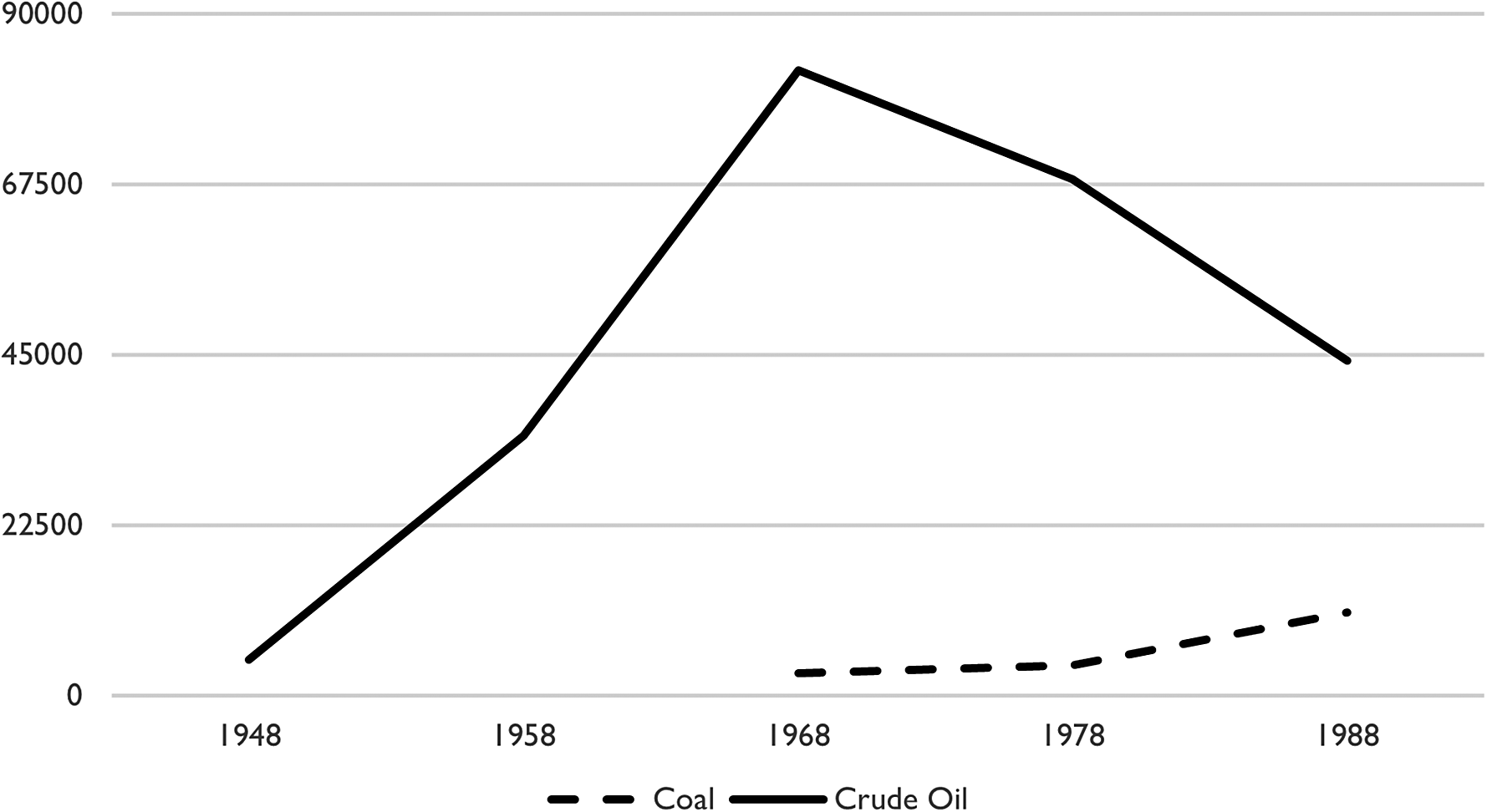

The scale and pace of the industry’s contraction (see Table 1) amplified this moral outrage. At nationalization, the NCB was responsible for 1,400 mines and a workforce of 695,000. By privatization in 1994, only eighteen deep mines operated employing around 9,000. These closures were directly affected by UK energy transitions. In 1960, coal accounted for 99 and 73 percent of UK energy production and consumption, respectively. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, coal steadily declined as part of the energy mix and became increasingly reliant on electricity generation and industry (especially steel), mostly replaced by oil imports (see Figures 1 and 2). By 1990, coal accounted for 27 and 30 percent of energy generated and consumed, respectively.Footnote 8 However, the frustration of those in the industry was also directed at the inconsistency of UK energy policy (it was not until 1967 that Britain produced a clear position in Energy Policy) and management of the contraction of British coal. This contrasted with other large European coal producers. As Martin Chick observes, the marked difference between the nationalized French and British coal mining industries was significant: “In proportionate and numerical terms the shedding of mining labor was much greater in the UK than in France, while the proportion of energy requirements derived from coal remained higher.”Footnote 9 One of the features of the closures was the regional inequities (see Table 1) that transformed the politics of mining unions and undermined the cohesion of one nationalized industry.

Table 1. Operational collieries in the British coalfield (1947–1994)

Note (compiled from): Catterall “Lancashire Coalfield”; Coal News; Colliery Guardian; DTI, Coal Review (1994); Francis and Smith, Fed; Gildart, North Wales Miners; Howell, The Politics of the NUM; NCB, ‘North-East Coal Digest 1983–4’; NUM, Nottingham Area; NUMSWA, Executive Council meeting minutes, 6 October 1987; Oglethorpe, Scottish Collieries; Perchard, Mine Management; Powell, The Power Game; Williams, Welsh Historical Statistics.

*Figures of operational collieries for 1994 are taken from after the DTI review of February. Operational figures for 1987 and 1994 should be treated with caution given the speed at which closures were being implemented (in the space of weeks rather than months).

Figure 1. UK Final Energy Consumption by Source, 1948–1988.

Note: Department of Energy & Climate Change, 60th Anniversary Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics (DUKES) (HMSO, 2009).

Figure 2. UK Coal and Crude Oil Imports, 1948–1988 (mts).

Note: DUKES (2009); Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), Crude oil and petroleum products imports by products, 1920–2021; BEIS, Historical Coal Data: Coal Production, 1853–2021.

Contribution

This study extends existing understandings of the impact of colliery closures on the industrial politics of the state-owned British coal industry, the largest socialized corporation in the world outside of the Communist Bloc, as morally constituted.Footnote 10 However, this national study goes beyond extant studies of the moral economy of the coalfields to suggest that in transgressing moral norms and processes, the NCB and especially the government undermined the integrity of public ownership. Miners’ anger at closures and their impact on coalfield communities was critical to the miners’ strikes of 1972, 1974, and 1984-5, the first national coal strikes since 1926. The Conservative governments after 1979 were able to exploit the growing sense of distrust of public ownership to further discredit it, move toward a wide program of privatization, and undermine a more consensual model of industrial relations. Through this national study, we respond to (1) resurgent interest in the character and conduct of public ownership, and (2) the impact of deindustrialization, considering renewed decarbonization initiatives.Footnote 11 We examine tensions evident in protests over closures, increasing centralization, inconsistent political interference, and growing alienation, peripheralization, and regional grievance arising from industry imbalances. Contiguous with prevailing changes to the UK’s energy mix and pressures over productivity, inconsistent policy direction and NCB governance, and the impact of the Aberfan disaster in October 1966, the waves of pit closures were a critical factor in undermining nationalization both among the industry’s workforce and coalfield communities.Footnote 12

We begin by examining and contextualizing nationalization’s sociolegal foundations. We note that although contested from the outset, moral considerations framed the political economy of coal and nationalization. While the Thatcher and Major administrations’ pursuit of colliery closures and abandonment of schemes to mitigate the social effects (pursued by preceding Labour and Conservative administrations to alleviate the effects) have correctly been identified as representing a sea change, tensions grew over the contraction of the industry from the late 1950s onwards. By the 1960s, coalfield anger had resulted in national mobilization, especially by the NUM. These are then located within discussions of moral economy. A key feature of these protests is that they became more identifiable as social movements, rather than being confined to industrial protests, with whole communities and other civic groups involved.Footnote 13 The article charts regional dynamics of the closures, reflecting the growing divisions within the nationalized industry: Between 1947 and the 1970s, pit closures fell hardest in the Durham, Cumberland, Lancashire, Northumberland, Scottish, and Welsh coalfields (Table 1). Concurrently, traditional markets and capital investment from these older coalfields were reallocated to the midlands and Yorkshire. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Warwickshire, and Yorkshire coalfields experienced closures much more acutely. The article explores these regional dynamics through phases during nationalization, highlighting the long-running process of deindustrialization: 1947–1957 charts the foundations of nationalization and the forging of an uneasy settlement between the NCB and the mining unions; 1958–1973 analyzes the escalation of closures and community activism politically mobilized into cross-coalfield protests feeding into the shifting politics of the NUM, national protests, and the first national coal strikes since 1926; 1974–1994 explores the temporary recovery of coal, the changed politics of the mining unions, and finally the onset of accelerated closures and assault on the mining unions under the Thatcher administration before the final contraction of British Coal prior to privatization in 1994. It also discusses different attempts at employee and community buyouts in the last few years of public ownership. As we note, closures were a significant factor in changing the mining unions’ industrial politics, and NCB officials’ growing disillusionment with the policies of successive governments.

The significance of charting the long-running and distinctive phases of closures lies both in elaborating how deindustrialization unfolded and the concomitant effects that it had on the industry and in responding to decontextualized revisionism in the public record.Footnote 14 Historians and sociologists alike have devoted particular attention to the role of industrial closures under the Wilson (1964–70) and Thatcher and Major (1979–1997) governments. A problem with such snapshots is that they lose sight of the dynamics of such closures across the long durée. As Phillips et al. noted, deindustrialization after 1945 was “a process rather than an event.”Footnote 15 This study of the response to closures by a large state-owned enterprise brings with it temporal and spatial comparisons, which will be of value to broader transnational comparisons of deindustrialization.Footnote 16

Regional divisions and inequities resulting from deindustrialization offer important insights into persistent regional imbalances. Social researchers tracking coalfield regeneration, employment patterns, and social deprivation over 30 years have revealed that despite UK government (and devolved Scottish and Welsh counterparts) initiatives, and even more generously the EU, coalfield areas disproportionately suffer from multiple deprivations and outward migration.Footnote 17 There is broader contemporary interest considering initiatives to decarbonize economies: “Those changes, and the interactions between work and place involved, have implications for the state as a critical institution in guiding and shaping how decarbonization initiatives unfold.“Footnote 18 Therefore, this article is also intended to contribute to understanding the roots of this social upheaval and regional disparities in coalfield areas, especially considering new policy initiatives, and to inform an understanding of “just” energy transitions.Footnote 19 The importance of understanding the profound consequences of such industrial contraction is acutely important; Judith Stein observed twenty years ago that voters and policymakers had become “anaesthetized” to “industrial decline.”Footnote 20 This was evident in the failure of national governments and supranational bodies, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to grasp the profound impacts and repercussions of deindustrialization.Footnote 21 More recently, policymakers have acknowledged the links between energy transitions, closure programs, and social inequalities. In 2019, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recognized the profound long-term effects of accelerated and poorly conceived energy transitions. In 2022, Scottish Government minister Fiona Hyslop made explicit the link between closures and “unjust energy transitions” during a Scottish Parliament debate around the Pardons Bill, an attempt to rectify the injustice of miners being unfairly convicted for public order offenses during the 1984–85 miners’ strike, which was explicitly above all industrial action intended to defend the industry against further closures. The significance of this study more generally lies in the legacy of confidence in public ownership and energy, industrial and regional policy more broadly, as well as in decarbonization and just energy transitions; for the sustained closures programs also had the effect of undermining confidence in coalfield areas in nationalization and government. It may also help, in part, to explain the political upheaval, especially in English mining constituencies.Footnote 22

This article presents the first national analysis of the implementation, impacts, and responses to closures examined from the perspectives of the NCB, and trade unions, and considers the role of the government, using archival sources, industry publications, contemporary documentaries, and oral testimony. The industry underwent several administrative changes during nationalization. The NCB (headquartered at Hobart House in London) initially had eight divisional boards reporting to it, with areas and subareas below those. This reflected the size and complexity of the industry. After 1967, these were reorganized into theoretically more autonomous areas, increasingly absorbing the former areas and subareas into two distinct subdivisions. These changes also reflected the contraction of certain coalfields and expansion of others, and tensions over the centralization of the industry. Alongside these from nationalization sat line and staff structures, later directorates, and a conciliation and consultations machinery. After 1987, the NCB was succeeded by the British Coal Corporation (BC), which oversaw the last years of public ownership until privatization in 1994. The NUM maintained a federalized structure (areas, districts, and lodges in England and Wales and branches in Scotland), which remained intact throughout nationalization, with one major rupture occurring with the emergence of the breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM) in December 1985 (chiefly in Nottinghamshire but with some members in several other coalfields) who represented many of the working miners during the 1984–85 miners’ strike. During nationalization, the central government department with the main responsibility for energy policy changed from the Ministry of Fuel and Power (1947–1957) to the Ministry of Power (1957–1969), the short-lived Ministry of Technology (1969–1970) before being absorbed into the Department of Energy (1974–1992), and finally the Department of Trade and Industry (1992–privatization). During this period, ten NCB/BC chairs reported to twenty-four Secretaries of State.

“On Behalf of the People”? Sociolegal Foundations of the Nationalized British Coal Industry

Understanding the sociolegal foundations of coal nationalization in Britain is necessary to foreground collective action against colliery closures. NCB Vesting Day ceremonies declared that the industry was managed “on behalf of the people.” The Coal Industry Nationalisation Act (CINA), 1946 held the NCB responsible for the health, safety, welfare, and training of those who worked for it, the efficient management of the industry, and meeting consumer demand.Footnote 23 The welfare provisions included the requirement to consider the social impact of industry closures; while drafting CINA, then Minister for Fuel and Power Emmanuel Shinwell (who represented a Durham mining constituency) insisted on a clause requiring the NCB to alleviate “social dislocations which might be caused by the closure of pits.“Footnote 24 While the miners’ unions had long campaigned for nationalization, and the Labour Party’s subcommittee on coal and power that informed its postwar reconstruction plans was chaired by Durham miners’ leader Sam Watson, Labour’s public ownership model owed more to Herbert Morrison’s Socialisation and Transport (published in 1933), informed by his experiences as a minister in the first Labour government of 1929–31 and establishing the London Passenger Transport Board. Socialisation and Transport were also informed by examples of joint stock companies and the civil service.Footnote 25 Morrison envisaged socialized industries that were “no mere capitalist business” and that aimed to: “promote the maximum of public well-being and the status, dignity, knowledge and freedom of the workers by hand and brain employed in the undertaking.”Footnote 26 He stipulated that they should be managed “in the splendid tradition of public service… as the high custodians of the public interest.”Footnote 27 As Lord President, Morrison stated during the parliamentary debate on coal nationalization in May 1946: “A public corporation gives […] a proper degree of public accountability.”Footnote 28 Morrison’s imprint was clear from the NCB’s first meeting: “It was the aim of the National Coal Board to inculcate into the whole industry the ideal of service to the commonweal.”Footnote 29 Similar sentiments were expressed publicly on Vesting Day.Footnote 30 Such moral rhetoric appealed to ideas of a “People’s Peace” after 1945.Footnote 31 It was also intended to mollify and win over opposition within and outside the industry. As political economist Sir Norman Chester observed of nationalization in 1952, it was just such, “attractive slogans, which sums up most of the public support for the corporation.”Footnote 32 However, it was in such broad appeals that Chester also envisaged future problems for these industries: “We are so used to compromises which give us much less than the best of both worlds that it is no wonder that an institution which claims to give us the best should have widespread support—and induce, in some, a degree of skepticism.”Footnote 33 As Robert Millward later noted, coal nationalization may have been unique among the nationalized industries, owing more to ideological foundations and the voice of the unions, but it was still subject to competing pressures.Footnote 34 Despite these varied demands, miners’ expectations, notwithstanding their skepticism, were for a socialized industry, explaining the growing coalfield frustrations at the industry’s organization and management. Fine, O’Donnell, Fishman, and Cumbers have all outlined the endemic problems with the foundations of Britain’s nationalization program and the inheritance of the industry, we further expand upon that understanding with respect to the disillusionment of those working in the industry and coalfield communities in relation to closures.Footnote 35 This research also comes on the back of more nuanced understandings of management within the nationalized industries, and their occupational location and moral objections to closures.Footnote 36 So here we demonstrate the various constituencies affected by colliery closures and their reactions.

Moral economy and deindustrialization

The sociolegal framing of coal nationalization reflected tenets of welfare economics and the sort of industrial citizenship espoused by the sociologist Thomas (T. H.) Marshall, marrying an attempt to introduce a fairer allocation of resources with their efficient management with the rights and responsibilities of employees, detectable not only in the nationalized corporations but also in several leading British companies, such as British Aluminium, Guinness, and Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI).Footnote 37 This was fundamentally rooted in the morality of the common weal. As such, exploring the moral economy of such ideals and rhetoric around nationalizing coal, alongside the realities, and the breakdown of such ideals among those employed in the industry and coalfield communities is vital to understanding the foundering of nationalization. The changing political context to this has received much attention elsewhere.Footnote 38 Recent studies of coalfield closures, particularly focusing on Scotland, have examined pit closures through E. P. Thompson and Andrew Sayer’s explanations of moral economy, and Karl Polanyi’s on the social embeddedness and disembeddedness of markets.Footnote 39

Thompson’s original identification of the moral economy of the eighteenth-century English crowd during food riots located these within broader shifts from Elizabethan welfare rights to a liberal market economy. This moral economic view was informed by:

… a consistent traditional view of social norms and obligations, of the proper economic functions of several parties within the community… An outrage to these moral assumptions, quite as much as actual deprivation, was the usual occasion for direct action. While this moral economy cannot be described as ‘political’ in any advanced sense, nevertheless it cannot be described as unpolitical either, since it supposed definite, and passionately held, notions of the common weal – notions which, indeed, found some support in the paternalist tradition of the authorities.Footnote 40

He began to articulate these ideas in his Making of the English Working Class: “In eighteenth-century England and France… the market remained a social as well as an economic nexus… The market was a place where the people because they were numerous, felt for a moment that they were strong.”Footnote 41 Thompson subsequently argued that these actions were motivated by “the notion of legitimation… men and women in the crowd were informed by the belief that they were defending traditional rights or customs; and, in general, that they were supported by the wider consensus of the community.“Footnote 42 While Thompson remained wary of the tendency for ahistorical applications of moral economy, he hinted at a broader historical extension of it, to encompass, “… ideal models or ideology (just as political ideology does), which assigns economic roles and customary practices (as alternative ‘economics’), in a particular balance of class and social forces.”Footnote 43 The transference of Thompsonian ideas of the moral economy beyond the original focus on the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries lies in this sense of collective resources, norms, and obligations: “[C]ommunity membership supersedes prices on the basis of entitlement.”Footnote 44 Tim Strangleman maintains that it is the “historical moment in which Thompson was concerned with, the experience of communities emerging into an industrial age,” that “can be usefully compared and contrasted with contemporary researchers studying communities experiencing deindustrialisation.”Footnote 45 For industrial communities contending with deindustrialization, he suggests: “People experiencing upheaval bring to bear previous patterns of understanding their circumstances in facing new circumstances… upheaval was understood and rendered intelligible by a shared set of customs held in common.“Footnote 46

Social scientist Andrew Sayer similarly identified the moral economy as less fixed: “[T]o some extent, moral-political values regarding economic activities and responsibilities co-evolve with economic systems.”Footnote 47 Jim Tomlinson has characterized 1940s Britain as just such a juncture at which the political imperatives of the war economy combined with a greater balance of social forces: “What marked the nineteen-forties was not a new awareness of the moral issues of economic life among intellectuals and policymakers, but a new political imperative to improve the performance of the economy at a time of full employment and with a citizenry empowered and energized by the exigencies of war.”Footnote 48 The program of reform, particularly public ownership, introduced by the Labour governments of 1945–51 was framed within a particular social contract and understanding of common weal. They are recognizable within Thompson’s moral economy and an “ideal model” and “alternative economics,” framed by a “particular balance of class and social forces.” This was incorporated into the “customary practices” of the nationalized coal industry, through its social obligations and commitment to joint negotiations and collective agreements, including around closures. These practices were subject to an evolving economic system and moral–political values, as recognized by Sayer. Nationalization’s “ideal model” was compromised from the outset. However, it was increasingly undermined during the 1960s and 1970s by closures, prompting disillusionment with the NCB and nationalization. Nevertheless, between the NCB and the mining unions, if not always the government, the established set of norms and practices were generally adhered to. The ascendancy of new liberal market thinking and its entrenchment in public policy in Britain after 1979 ruptured those irrevocably, with another moral economic vision with individualistic consumers and markets at the center, involving a scaling back of the state in the economy but one with the full use of state power to limit employment rights and trade unions. In the following decades, Conservative administrations sought to roll back the state, with the UK accounting for 40 percent of state assets privatized between 1980 and 1996.Footnote 49 As Tomlinson and Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite underline, the policies of the Thatcher and Major administrations, though socially disruptive, divisive, and harmful, were guided by equally strong moral convictions as those opposing them, including those within their own party.Footnote 50 However, in their zeal for reforming and liberalizing the British economy and stripping out employment rights and trade union representation, they were impassive to the social suffering that caused. Equally, policymakers in the preceding decades were blinded by a belief in rationalization and efficiency while mitigating the effects with material compensation. The gap between the rhetoric and obligations was evident within the first decade of nationalization.

However, the undue focus on material considerations (collective resources) in much of this work has imposed limitations in understanding the full cultural and social impacts of deindustrialization and the emotional and cultural content of Thompson’s work. They do not sufficiently capture the extent of the “avalanche of harms” (physical, psychological, political, social, moral, economic harms and harm to autonomy), as economist George DeMartino has described the impacts of certain economic policy decisions, including deindustrialization, and the feelings that accompany those. The groundswell of anger in coalfield communities, like other deindustrializing areas, during the period studied here, speaks to the emotions of these far more profound.Footnote 51 Eisenberg and Lazarsfeld captured some sense of this in their influential 1938 study of unemployment (partly informed by Marie Jahoda, Paul Lazarsfeld, and Hans Zeisel’s study of the depressed Austrian textile town of Marienthal): “When we try to formulate more exactly the psychological effects of unemployment, we lose the full, poignant, emotional feeling that this word brings to people.”Footnote 52 The “avalanche of harms” of industrial closures has been long recognized by deindustrialization scholars, as recognized by Cowie and Heathcott in their call to look “beyond the body counts” (examining the profound impact behind the jobless claimant numbers) to Linkon’s notion of the “half-life of deindustrialization,” as a painful drawn-out process with multigenerational implications.Footnote 53 In the periods that follow we chart the groundswell of coalfield protests growing to national proportions and the changing industrial politics of the mining unions, fueled by moral outrage at the failure to accord with the spirit of norms and practices. What top-down planning, even of a welfarist nature, with its extolling of negotiated settlements and compensation, failed to appreciate was the full and profound effects of uprooting families and upending communities that colliery closures entailed. The closures of the 1980s and 1990s, also top-down but after 1985 (with the defeat of the NUM) with little semblance of meaningful negotiation or prospect of reprieve, were even more devastating.

1947–1957: “Attractive slogans” and compromises

Ten years after nationalization, NCB Chairman James Bowman (1956–1961) addressed the NUM conference:

Nationalisation meant many things to many people, but one thing is certain. To the industry it meant the chance to expand. To expand both for the benefit of those who work in it, and for the benefit of the country… we in this industry must co-operate in achieving our common interests. We must indeed march together. For let me assure you that, just as we have common interests, so, to achieve the things we all want, we must strive to have a common policy and a common viewpoint.Footnote 54

A former Northumberland miner and NUM vice president, Bowman’s optimistic rhetoric sought to draw on his capital with the Union, smoothing over growing discord in the coalfields and eliciting greater efforts from miners. The speech formed part of the NCB’s public relations team’s tenth-anniversary celebrations but was also a call for greater unity in an industry that was struggling.Footnote 55

Despite still providing around 70 percent of the energy consumed by the late 1950s, including industrial customers vital to maintaining exports to meet Britain’s balance of payment difficulties, the industry confronted growing pressures. The NCB faced a growing challenge from oil imports and less significantly the advent of the new Magnox nuclear power stations at Calder Hall, in Cumbria, and Chapelcross, Dumfries and Galloway (see Figures 1 and 2). Pressures to maximize coal production and achieve efficiency gains, while addressing a legacy of decades of underinvestment in the industry, centered around large capital projects and a steady process of modernization to raise productivity. The coalfield planners’ remedy both before and after nationalization was to concentrate capital investment and production in new large collieries with integrated faces and to phase out older, smaller pits. This policy sought to address immediate demand and develop the future of the industry, but it fell short in its long-term management of mineral reserves and in meeting the NCB social commitments.Footnote 56 The centralization of management structures created further tensions; as the Acton Society Trust observed in 1951, particularly regarding the NCB: “The nationalised industries are large and immensely complex. They have inherited from before nationalisation a great range of practices, and have so far only made a start on formalizing and reconciling them.”Footnote 57 Increasingly coal’s position as the dominant energy source was maintained via stockpiling and contracts with the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) and South of Scotland Electricity Generating Board. By the late 1950s, the precipitous rise in coal stockpiles started to create greater issues for the NCB. This was exacerbated by the lack of a clear UK energy policy. For all the idealism, formal trade union recognition, and industrial relations, the industry also suffered from considerable suspicion between miners and the new NCB, with the management of the industry predominantly left in the hands of board members and regional and colliery management leftover from the private industry causing considerable tensions.Footnote 58 Such recognition of differences between the rhetoric and realities of the NCB demonstrates the challenges of establishing a morally constituted nationalized industry.

A combination of these pressures meant that even with the NCB‘s industrial relations machinery and the rhetoric of partnership, the conduct of workplace relations at a local level was much more fraught. Over the first sixteen years of nationalization, the industry experienced hundreds of small, localized strikes, particularly in the Scottish, South Wales, Lancastrian, and Yorkshire coalfields, including a strike involving forty-three Scottish pits in 1950.Footnote 59 The fact that there were no national strikes in the first two decades owed more to the NUM leadership’s accommodation of and support for nationalization.Footnote 60 The challenges of balancing the NCB‘s moral obligations were also highlighted by its scheme to employ disabled miners, especially those suffering from coal dust pneumoconiosis, with some within the NUM viewing this as a threat while others within the NUM and the NCB seeking to maintain it to protect those facing destitution, with such schemes being made ever more difficult to maintain in the face of closures.Footnote 61 This was not the period of industrial harmony that the absence of national strikes suggested, and serious discontent was brewing in the Durham, Northumberland, Scottish, and Welsh coalfields over closures.

As in subsequent decades, closures fell disproportionately on certain coalfields, with most collieries closed in this period in Scotland and south Wales (table 1). The Scottish coalfield illustrated the problems and tensions within the industry. Even with forty-three collieries closed between 1947 and 1957, NCB officials remained sanguine about the coalfield’s prospects; the 1950 Plan for Coal declared that “for the Scottish Coalfields taken as a whole, the future is a good one.”Footnote 62 Meanwhile, NCB Scottish Division (NCB SD) Chair Dr. William Reid concluded in 1953: “Scotland’s coal reserves are recognized to be second in importance only to those of Yorkshire and the East Midlands, and from this, it may be confidently adduced that Scotland’s place in the mining future of this country is an assured one.”Footnote 63 The NCB portrayed closures in this period as the result of careful planning and consultation; “The difference is between planning and chaos. Lanarkshire must not again become a depressed area,” as the first NCB SD Chair Lord Balfour put it in the NCB’s Mining Review for1949, focusing on the closure of pits in Lanarkshire and the transfer of miners to collieries in Fife. Like other NCB public relations of the time, “Replanning a Coalfield” contrasted the rationalism of national planning and consultation with interwar conflict and uncertainty.Footnote 64

The NCB faced considerable challenges, including in sourcing materials against the competing demands of reconstruction and Korean War rearmament, in the first few years seeking to balance national demands for increased production with major capital investment projects in an industry that had been starved of funding. Nevertheless, between 1947 and 1950, the NCB invested £93.5 million in new projects (£3.4 billion in 2021 prices). However, the NCB’s strategy of concentrating production in larger units, “Super Pits,” also culminated in some catastrophes, particularly in Scotland, with a profound impact on divisional finances and future investment.Footnote 65 A notable example of this was the Rothes Colliery (Fife), around which the new town of Glenrothes was built to house miners and their families transferring from other areas to work at the colliery. Projected to have a lifespan of 100 years, the costs of this new super pit spiraled from an estimated £1.5 million (around £38.5 million, 2021) to £20 million (£513 million) upon completion in 1957. By 1959, Rothes was servicing annual operating losses of £3.7 million (£91.6 million) and had to abandon fourteen of its sixteen operational faces. It closed in 1962 due to severe geological problems, which they had been warned about both by local mining engineers and the mining unions. Among those miners who were meant to have been relocated were Lanarkshire miners featured in the Mining Review’s “Replanning a Coalfield.” Similarly, the major reconstruction of Glenochil Mine (Alloa) between 1952 and 1957 cost the Division £1.3 million (£33.3 million) and never achieved operational projections, with major flooding forcing its closure in 1962. Again, several government departments warned the Division about its feasibility. The shortcomings in planning also resulted from private colliery companies overstating the potential of these sites to maximize the valuation price they were paid and former senior staff from those same companies who had joined the NCB SD board and sanctioned the development of these schemes. These all had major repercussions for the Division both immediately in terms of production, employment, and regional infrastructure investment, and longer-term confidence in it, as the rescue of Barony colliery (discussed later) would demonstrate. By 1962, NUM Scottish Area (NUMSA) president Alex Moffat presented a bleak picture of the Scottish coalfield at the NUM conference: “While you in some districts are talking about the closure of collieries that have been operating for probably 100 years we have been faced with the closure of collieries and half-developed collieries that were expected to give new life to the Scottish coalfield.”Footnote 66

NCB rhetoric about consensus, planning, and the ease of relocating miners masked the very real difficulties that were already being experienced. In contrast to the NCB’s optimism in “Replanning a Coalfied,” Lanarkshire coalfield closures in the first decade of nationalization did not go uncontested. A 1953 study of the closures and transfers from Lanarkshire to Fife exposed the problems with the transfer schemes with many Lanarkshire miners returning because they could not adjust to working conditions in Fife pits and missed their communities.Footnote 67 Phillips noted that there was also tension in receiving communities like Lochore (Fife) at “outsiders” taking jobs off “local lads.”Footnote 68 As Hazel Heughan observed at the time and Ewan Gibbs has detailed for Lanarkshire, even in the face of these agreements, there was considerable pushback against transfer schemes both because of the disruption of communities and workplace relations and conditions.Footnote 69 The practicalities of transferring miners against the backdrop of Britain’s straightened economic circumstances in the immediate postwar period was also apparent in the vicinity of Barony Colliery (Ayrshire), marked for modernization as one of the NCB SD’s largest producers, and drawing its workforce from a 30-mile radius (including Lanarkshire miners). Nearby Cumnock Town Council struggled to meet the demands for housing and social infrastructure miners coming into the area to work at Barony.Footnote 70 The discontent evident in local responses often exposed the gap between the NCB’s social obligations and rhetoric, on the one hand, and reality, on the other.

From the mid-1950s onwards, the NCB also targeted investment to prioritize the transition to power-loaded faces. As with the ‘super pit’ initiatives, NCB planning of integrated power-loaded production often failed to factor in local geological conditions inherent in coal mining, creating tensions with local colliery management and miners. Such planning was also frequently not accompanied by the modernization of underground and pithead transport, which affected overall productivity figures. The focus on power-loaded coalfaces significantly increased the unit costs of coal production and expectations on returns. By the late 1950s, a cutter–loader cost around £40 thousand per unit (£990 thousand). In Scotland, by the mid-1960s, the standard coalface had a life of six months often with very thin seams of coal and severe gradients, ill-suited to adapting to power-loaded faces. However, between 1960 and 1964, power-loaded production increased from around 28 percent of output to 62 percent in Scotland. The situation was further aggravated by the imposition of centrally devised productivity targets calculated from national averages from the mid-1960s onwards. The net result of such a production policy was to push many more collieries into the “uneconomic” category.Footnote 71 As the NCB’s Chief Economist Fritz Schumacher was to warn about such categorization at a NUM conference in 1960 and its implications for long-term natural resource management:

… the concepts of ‘economic’ and ‘uneconomic’ cannot be applied to the extraction of non-renewable resources without very great caution… to close the losing colliery means merely to change the time sequence in which finite resources are being used… It is a policy of doubtful wisdom and questionable morality for this generation to take all the best resources and leave for its children only the worst. But is surely a criminal policy if, in addition, we willfully sterilize, abandon, and thereby ruin such relatively inferior resources as we ourselves have opened up but do not care to utilize.Footnote 72

In the face of inconsistent policy priorities and increased competition from other energy sources, NCB Chairs Bowman and Lord Robens (1961–1971) prioritized increased production from reorganized and mechanized coal faces driven by increasingly centralized targets and divisional power loading agreements (which introduced day wages for different classes of workers) leading up to the National Power Loading Agreement of 1966. This further exacerbated emerging problems in the coalfields over closures, especially in the northeast of England, Scotland, and Wales.

As the nationalized British coal industry celebrated its tenth anniversary, it could justifiably point to substantial investment in the industry, increased industrial democracy, health and social benefits, and occupational development opportunities for those who worked in the industry. It had risen to meet Britain’s energy needs in a time of dire economic need and reconstruction. These embodied the “ideal model” of a common weal and a balance of “class and social forces.” Nationalization’s social contract forged a precarious peace between the NCB, mining unions, and the government. However, the demands on miners and their families, particularly in the face of the onslaught of closures in the ensuing long decade put the social contract to the test.

1958–1973: “a secure job … with a future too”?

Growing coalfield protests over closures, especially in the north of England, Scotland, and Wales, became even more acute by the late 1950s. Escalating closures reflected an increasingly challenging energy situation for coal, with growing competition and contraction of markets, and concentration of production, as well as a less accommodating policy environment and growing tensions between the NCB and government. These tensions with the NCB and dissent with the national NUM leadership were reflected in the proliferation of strikes, which grew both in number and participation, rising by 78 percent between 1953 and 1958 alone.Footnote 73 A younger generation of NUM activists further mobilized coalfield anger into national protests. Another notable feature of the campaigns against closure was that the protests, which had traditionally come from the more historically radical coalfields (Scotland and south Wales), increasingly drew support from coalfields noted for their political moderation and loyalty to the NUM leadership (Durham, Lancashire, and north Wales). Importantly, colliery management and BACM were also more vocal in their dissent, as Perchard and Gildart observe, this was not only because management jobs were at threat but also because managers were themselves often raised in mining communities and also saw the pits as collective resources.Footnote 74 This moral outrage, arising from the apparent neglect of the NCB and the government’s social obligations and the top-down disregard of local opinion, was illustrated through several episodes.

In 1958, the NCB announced the closure of Blackhill Colliery in Bowman’s native coalfield in Northumberland. The colliery workforce challenged the decision and established a community-based campaign to fight the closure, bringing them into conflict with the NUM and the NCB. The colliery is chiefly remembered because of a poignant film, The Blackhill Campaign (1963), made by former NCB researcher and film producer Jack Parsons, capturing the failed campaign to save the colliery. In contrast to the patrician NCB films, it was narrated by George Richardson, a miner who joined the industry in 1911. The Blackhill Campaign began with Richardson describing his long service and the pneumoconiosis that mining had afflicted him with, before panning to an NCB recruitment poster promising a “secure job …with a future too.” The film portrays coal as a community resource; early footage describes the sinking of the shaft by the miners themselves in 1942 to meet demands for the war effort and highlights the importance of the colliery to the village (including NCB investment in housing).Footnote 75 The Blackhill campaign deployed the moral rhetoric of settled norms and obligations and was also a civic campaign. The same year, Cumberland miners’ leader and NUM executive member, Tom Stephenson, railed against an NCB, “run by men whose idea of public ownership far from coincide with the minds of those who legislated for this change … those in charge of the Board’s side are completely out of touch with feelings of those they employ.”Footnote 76 The miners at Blackhill and Cumberland asserted their moral economic rights and questioned the NCB’s legitimacy in depriving their communities of their very existence.

In June 1959, miners at Devon Colliery in Scotland, including large numbers recently uprooted from Lanarkshire, embarked on a stay-down protest leading to an unofficial strike at forty-six other collieries involving 25,000 miners, following the NCB’s announcement of closure. NUMSA president Abe Moffat managed to negotiate an end to the strike and an insistence on consultation.Footnote 77 A month later, at the NUM annual conference, Moffat proposed a resolution opposing further closures. Following NUM president (and former Yorkshire miner) Ernest Jones’ attempts to defeat the resolution, Moffat drew particular attention to the plight of Scotland and south Wales and how this would impact the solidarity of the union: “If the National Coal Board operate these closures just against Scotland and South Wales, then it is a deliberate policy to break the unity of our union … I can’t understand why some of our leaders in the present circumstances ask us to thank God for the National Coal Board.”Footnote 78 Moffat’s resolution was passed reflecting growing anger at the NCB and discontent with the NUM leadership. Moffat’s pointed warning about the “unity of our union” was a reflection not only of the tensions between NUM area executives and branches/lodges, but also a sense of the growing disparity between coalfields, with closures falling disproportionately in the north of England, Scotland, and South Wales. In Durham, more than half of the 124 collieries in operation in 1947 had closed, with the loss of 55,462 mining jobs, while Lancashire lost forty-three collieries. Scotland saw 159 pits closed, with 50,000 jobs lost. It was a similar picture in South Wales, where 121 collieries closed, and 57,700 jobs went.Footnote 79

Bowman’s calls for industry unity were undermined by the NCB and the government’s treatment of different coalfields, with local officials and union leaders angered by the disparity of treatment. In 1959, an Ayrshire coalfield delegation met with the Ministry of Power (MoP) Parliamentary Secretary John George to protest the reallocation of Irish contracts from Ayrshire to the East Midlands Area (which had a coal surplus). If the delegation expected reassurances from George, they met with none. George, who had worked as a miner and subsequently became the Managing Director of New Cumnock Collieries (an Ayrshire colliery company) before nationalization, had been a vehement opponent of nationalization.Footnote 80 Earlier that year, MoP officials estimated that the NCB might only be able to absorb 56 percent of Scottish miners from closed collieries immediately, with the possibility of a further 10 percent within six months.Footnote 81 By December 1962, MoP officials acknowledged the inequity between the financial targets imposed on the Scottish Division and their Midlands counterparts in the context of further announced closures:

[The] Scottish Division has estimated that its losses for 1963 will be reduced to £1.6 million. Despite this, however, Hobart House is requiring the Board to reduce this to £ 0.7 million. This is regarded as squeezing the Board very hard indeed and appears to be about 2 ½ times the amount called for from the West Midlands Board … So, unless the Board can show justification on grounds of fall in demand, it will be very difficult to get the Union’s agreement to their closure.Footnote 82

It was just such disparity that would also inform NUMSA’s later championing of home rule for Scotland.Footnote 83

The NCB’s response to closures was to transfer miners, mainly to collieries in the English Midlands and Yorkshire, while the government sought in a piecemeal fashion to encourage alternative employment with limited success.Footnote 84 Between 1962 and 1971, 15,000 miners and their families from Durham, Northumberland, and Scotland migrated.Footnote 85 The Coal Industry Housing Association (CIHA) undertook large building projects in Clipstone, Ollerton, Wellbeck, Rainworth, Sutton, Kirby, and Mansfield in Nottinghamshire to house miners.Footnote 86 However, the NCB’s gloss failed to mask the reality. Bob Fall’s story was illustrative; the thousandth Durham miner transferred to the East Midlands Division, and thirty-year-old Fall moved to Cotes Park Colliery, which closed six months later.Footnote 87 As the NCB, the Scottish and Welsh Offices, and regional development authorities in the northeast of England, were discovering, despite the CIHA housing programs and the board’s public relations campaigns, many miners and their families were increasingly unwilling to uproot their families from kinship networks. Consequently, working groups examining these questions reported in 1967: “It was suggested that the extra housing program had not proved much help in getting miners to transfer to other areas. In some parts of the Midlands, houses were standing empty.”Footnote 88 Such initiatives underlined the limitations of a system of centralized planning, which was increasingly associated not only with pit closures by the dislocation of mining families and the dissolution of communities. Where alternative employment existed, it also led to some miners leaving the industry rather than their communities and family networks.Footnote 89

The NCB’s growing awareness of the problems posed by closures and transfers was revealed in Coal News and Mining Review. In November 1962, Coal News covered the transfer of 540 miners from Parkham Colliery in Derbyshire, who were to be bussed by the NCB for their shift forty minutes’ drive away, but assured readers that, “the transfer scheme cuts difficulties,” emphasizing that no income would be lost to the local area.Footnote 90 Though Derbyshire had been less acutely affected by closures at this time, they were beginning to increase, and north Derbyshire alone shed 15,100 mining jobs between 1957 and 1967.Footnote 91 In Mining Review’s “A story from South Wales” (1963), a youthful mining engineer (Phillip Weekes, later NCB South Wales Area Director) presented a more compassionate view of the planned restructuring of the coalfields: “[I]t has to be done gently and with consideration.”Footnote 92 This contrasted technocratic planning with the chaos of the interwar years but sought to present a more human face, with Weekes intimating: “I know the effect this can have. And I’ve seen the effect that this has had in Welsh Valleys.”Footnote 93

NCB colliery closures also increasingly posed a growing capacity and capability issue: the irrevocable loss of underground workings; and young miners leaving the industry in coalfields where there were viable alternatives. For older miners, finding alternative employment was more difficult. By February 1965 in Fife, 1,593 miners were already being paid under the NCB Redundancy Recruitment Scheme. Managers were also affected. In 1958–9, 60 percent of managers affected by the closure of thirty Scottish collieries could not be placed, while officials at seven colliery closures in Cumberland and Northumberland in the same period were either demoted, given short-term contracts, or not placed.Footnote 94 By the summer of 1962, the NUM conference supported a motion called by the small Cumberland Area, which had been decimated by the closure of twelve collieries during the 1950s and 1960s, “opposing pit closures which sterilised reserves regardless of the needs of the community and security of employment of workers.”Footnote 95

Bowman’s replacement, Lord Robens, captured the scale and pace of the problem: “My ten years have seen more than 400 pits closed and 64,200 men made redundant. Even if the closures had been spread evenly over the ten years and evenly over the coalfields, there could easily have been strikes on a big scale… At one time we were shutting an average of three pits every fortnight…”Footnote 96 Robens, a former Labour minister, faced an increasingly hostile reception within government to coal and the wish to replace it with imported oil and nuclear power. In 1963, Robens refused Conservative Minister of Power Richard Wood’s request for further closures, stressing that the existing program was the largest they “could negotiate with the unions in a peaceful manner.”Footnote 97 Under Wilson’s Labour administrations (1964–70), Robens clashed with successive Ministers of Power, Fred Lee, and Richard Marsh, with Marsh particularly hostile to coal.Footnote 98 This presaged the national protests of the late 1960s and the 1972 and 1974 strikes. The fragile industrial relations were at a breaking point under pressure from ministers’ hostility and inconsistency. Acknowledging the damage wrought by coalfield closures, Fritz Schumacher remarked in a speech in December 1969: “[T]he last ten years have played havoc with the industry. To my mind it is a marvel that it has been possible to hold a situation of relative industrial peace, but there has been a delayed action effect and we are moving into a situation of much tighter industrial relations.”Footnote 99 The national strikes were avoided in the 1960s resulting from the NUM national executive’s maintenance of a consensus with the NCB. As coalfield protests and votes at the NUM conference indicated, that was changing. In Scotland and south Wales, miners’ leaders who vehemently opposed closures, such as Daly, Francis, and McGahey, were gaining influence. In Durham, by contrast, Watson’s dominance ensured that even after his retirement in 1963, the Area maintained a consensus with the NCB despite significant closures. Alf Hesler, Watson’s successor, accepted rationalization, admonishing those protesting the closure of an additional thirty-six Durham collieries in 1965.Footnote 100 Hesler wished to maintain his Area’s loyalty to the NCB and the Labour Party.Footnote 101 Such loyalism was also evident in Northumberland, principally through the legacy of leaders such as Bowman.Footnote 102

In the historically politically moderate Lancashire and north Wales coalfields, anger was also bubbling over. In north Wales, almost 50 percent of jobs were cut between 1957 and 1967, with the NUM at Llay Main and Hafod collieries leading community campaigns to save them from closure between 1966 and 1969.Footnote 103 Acknowledging the tensions between the local colliery management and NUM and the NCB Area office, colliery manager (and future MP and MEP for the area) Tom Ellis noted: “[T]his seemed to people at the colliery to be no more than a churlish intransigence.”Footnote 104 In Lancashire, NUM divisions emerged over Mosley Common Colliery’s closure, with future NUM President Joe Gormley blaming the closure on “militant” members of his own union: “[I]t was the miners themselves who closed the pit.”Footnote 105 In south Wales, there were local strikes and protests over the closures of Rhigos and Glyncastle in January 1965, Cambrian in September 1966, and Ynyscedwyn and Cefn Coed collieries in February 1968, as well as protest motions against closures at the 1966 and 1968 Area conferences.Footnote 106 Significantly, the miners’ contingent that stormed the 1968 Labour Party conference was from South Wales.Footnote 107 By 1969, the NUMSWA leadership recommended strike action over the announcement of the closure of Avon Colliery. However, the Area conference rejected this with members concerned about the survival of their own collieries.Footnote 108 In Scotland, at Woodend Colliery in Lanarkshire, the NUM and the local management resisted for three years before the colliery closed in 1965.Footnote 109 In most cases, these campaigns did not save the collieries concerned. However, successful area and community-based mobilization to save Barony Colliery in Ayrshire between 1962 and 1965 demonstrated the range of grievances being aired about closures against the NUM leadership, the NCB, and the government, and the moral economic rights being asserted by mining communities, and the effectiveness of timely broad civic campaigns.Footnote 110 However, Barony’s reprieve was followed by a wave of Scottish closures over the winter of 1967–1968.Footnote 111

Anger in the coalfields had been growing for some time. In 1966, NUMSA official Michael McGahey described colliery closures at a meeting in Ayrshire as, “the deliberate, premeditated murder of an industry.”Footnote 112 McGahey’s condemnation reflected the 50,000 jobs lost in the Scottish coalfields since nationalization in 1947.Footnote 113 Upon becoming NUMSA President in 1967, McGahey reversed the accommodation of closures by his predecessor and fellow veteran Communist, Abe Moffat, arguing: “I reject the present approach taken in many quarters which would make the cost of coal the sole criterion for determining the future size of the industry.”Footnote 114 Meanwhile, NUM South Wales Area (NUMSWA) General Secretary Dai Francis voiced miners’ frustration when meeting with the Secretary of State for Wales: “We do not want a perpetuation of Tory policy … It is my personal opinion that this Government is intent on creating … unemployment.”Footnote 115 By 1967, 57,700 mining jobs had been lost in south Wales.Footnote 116 At the 1968 Labour Party conference in Blackpool, miners invaded the floor to protest further closures.Footnote 117

The growing national dimension of the protests was also changing the NUM. In January 1969, former NUMSA General Secretary Lawrence Daly succeeded Paynter in the election for NUM general secretary. As a NUMSWA official in the late 1950s, Paynter had been outspoken about closures but had stopped short of calling for industrial action on the issue.Footnote 118 A tribute to Paynter in NUM newspaper, The Miner, praised him for seeing, “that the idea of militant resistance to the contraction of the industry was wrong-headed and futile.”Footnote 119 Paynter was constrained by the NUM leadership’s national strategy, between 1947 and the early 1960s, of accommodation with the NCB and the Labour Party to protect nationalization, as advocated by long-standing miners’ leaders such as Will Lawther, Sam Watson, and Alf Hesler (Durham); and Ted Jones (North Wales). Daly’s victory, like McGahey’s, signaled a perceptible change in the NUM’s rhetoric and tactics over colliery closures, and its relationship with the NCB and Labour. Daly and McGahey represented a new generation of coalfield leaders who emerged in opposition to coalfield closures.Footnote 120 In his first column for The Miner as general secretary, Daly attacked the NCB for “a record of the worst kind” on closures.Footnote 121 Interviewed in the 1970s, long-serving NUMSWA General Secretary and Chair of the Wales Trades Union Congress Dai Francis was unequivocal about what undermined the NCB: “[P]it closures, unquestionably.”Footnote 122

NCB officials shared miners’ frustrations. By the early 1970s, the British Association of Colliery Management (BACM) and the National Association of Colliery Oversmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS)—the unions respectively for managers and under officials—joined the NUM in lobbying against closures. BACM’s politics had also changed with a far more combative President and General Secretary.Footnote 123 In a 1969 BBC documentary, BACM president Jim Bullock noted the anger of his members, remarking: “Closing a pit … means destroying a whole community.”Footnote 124 Managers’ growing rancor over closures was articulated at the BACM branch and national levels.Footnote 125 BACM’s rhetoric similarly echoed the loss of collective resources and the abandonment of settled norms and obligations. The NUM National Executive Committee’s adoption of reviewed procedures in 1967, and subsequently the letter from the mining unions (BACM, NACODS, and NUM) and the NCB to the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry in 1972, sought greater influence for the unions on colliery review procedures than those established in the National Appeals Procedure in the late 1940s.Footnote 126 The public protests reflected profound moral outrage at personal and collective losses for mining communities. Whatever the contested nature of nationalization at the time or retrospectively, the political commitments, legal requirements, and NCB rhetoric were invested with moral obligations to NCB employees, notably around closures.

The “Great Demonstration” in November 1967 and the protest at Labour’s 1968 Blackpool conference marked a watershed in drawing public attention nationally to pit closures and the plight of pit villages. Crucially, such exposure also highlighted the impact on families, the neglect of moral obligations, and as with Thompson’s eighteenth-century protestors, “the wider consensus of the community.”Footnote 127 One Ashington miner’s wife, Jean Kirkup, interviewed for the 1967 Man Alive documentary, was indicative: “The area was booming at one time but lately it has gone downhill and neither one government nor the other has lifted a hand to help it.”Footnote 128 NCB headquarters staff also expressed growing frustration at government interference and myopia over fuel policy. The growing animosity between the NCB and the Labour Government was palpable, with assistant chief economist George McRobie observing that Robens, Schumacher, and others “hated” Wilson and considered him untrustworthy. For McRobie this was about the erosion of nationalization: “The ideal was wittered away. The ministers wanted the industry to be run like a large capitalist industry—social aims were not really taken into account.”Footnote 129 Coalfield anger also affected national politics. Colliery closures factored into Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru by-election successes in Scotland and Wales, with Labour membership starting to decline in their heartlands. Closures directly informed the growing campaign for Scottish home rule, with the NUM responsible for changing STUC attitudes and prominent in the growing civic movement for devolution.Footnote 130

While the miners’ strike of 1972 has been ascribed to the leftward shift in the NUM, few at the time pointed to the underlying anger associated with closures, including in politically moderate NUM areas.Footnote 131 By 1972 it was the Durham miners who proposed a resolution to the NUM conference opposing closures.Footnote 132 In north Wales, closures were transforming communities and engendering an acute sense of loss and distress. The closure of Gresford in Wrexham in 1973 was indicative. The NUM organized an unsuccessful campaign including local NCB managers and Labour MPs. Jack Read, a NUM official at the pit, penned a poignant message for the last meeting of the Lodge. It simply read: “[T]here does not seem any more purpose in what I do.”Footnote 133 By the late 1960s, coalfield anger, mobilized in community and rank-and-file action, was transforming the mining unions’ industrial politics, breeding a sense of alienation among the NCB, and had coalesced into national action. The nature of these campaigns and the rhetoric deployed spoke to a sense of settled norms and obligations undermined and of a growing distrust in policymakers.

1974–1994: Reprieve and demise

Labour’s 1974 Plan for Coal represented the last significant commitment to invest in coal and stem the decline, following the 1973 oil crisis, the 1972 and 1974 miners’ strikes (and the downfall of the Heath government), and a recognition of the need for energy security. Some of the NCB’s largest customers were sympathetic, with Central Electricity Generating Board Chairman, Arthur Hawkins, acknowledging to NCB Chairman Derek Ezra in 1975: “The Generating Board is not unmindful of the problems facing you, nor would it wish to deny the face-worker and underground worker in the mines a proper reward for their arduous work in conditions that few would like to share.”Footnote 134 Ezra and Gormley sought to manage the uneasy peace through pragmatic brokering; “the celebrated Derek and Joe act.”Footnote 135 The problem confronting the NUM nationally in opposing closures was the reluctance of members in some coalfields to support industrial action; NUMSWA supported the campaign to save Deep Duffryn Colliery, identified for closure in 1978, by contrast only 28 percent of miners voted to support a strike to prevent the closure of Teveral in Nottinghamshire in February 1979.Footnote 136

Thatcher’s government, elected in 1979 (reelected in 1983 and 1987), accelerated the closure program and pursued an end to nationalization. Following new financial measures under the Coal Industry Act (1980), in February 19811 the NCB announced 50 closures. Even before these were announced, male unemployment rates were over 10 percent in coalfield areas, well above the national average.Footnote 137 South Wales, where five of the proposed closures were located, led the opposition. NUMSWA sought the support of other Areas; Durham, Kent, and Scotland joined the strike. Faced with this rapidly escalating situation, an already precarious government withdrew the plans. This was significant because it suggested that swift, coalfield-by-coalfield “domino effect” strike action by the NUM could succeed in preventing colliery closures.Footnote 138 However, it exposed internal divisions and weaknesses, which the government (intent on weakening the NUM) studied carefully. Flying pickets entered north Wales confronting miners at Point of Ayr Colliery. Ted McKay, the area representative on the NUM executive, labeled the pickets “yobbos” and “bully boys.”Footnote 139 BACM President Norman Schofield also forcefully opposed the accelerated closure plan in meetings with the NCB and the government.Footnote 140 In 1983, the closure of Cronton, close to Liverpool, was announced, followed by Haig, Cumberland’s last colliery, with little opposition from local miners. Such divisions within some moderate areas of the NUM over closures minimized the effectiveness of the strike that followed in 1984–5.Footnote 141 By July 1983, unemployment in coalfield areas stood at nearly 15.8 percent (with the national average at 13.8).Footnote 142 Increasingly the NCB adopted the tactic of reducing manpower while demanding unrealistic targets and leaking stories to the media about production issues, as a prelude to categorizing the colliery as unprofitable. Ultimately with growing industry opposition to accelerated closures, as well as a prepared plan of attack on the NUM (and other mining unions), the Conservative government appointed the deeply unpopular Ian MacGregor as NCB chairman in 1983.Footnote 143

The assault on the industry started before MacGregor’s appointment, with some area directors, notably Albert Wheeler in Scotland, as well as John Northard (North Western) and Ken Moses (North Derbyshire), gaining notoriety for their rejection of established practices of consultation and replacing managers that did not adhere to their approach.Footnote 144 Nevertheless, some managers mounted public and private opposition before and after MacGregor‘s appointment. BACM, a privately robust critic of accelerated closures under Ezra, became a vocal public opponent of MacGregor even before his appointment on the basis of his track record at British Steel.Footnote 145 NCB South Wales Director Phillip Weekes, alongside other nationalized industry leaders in Wales, sought greater protection by proposing to bring them under Welsh Office control. Weekes resolutely opposed both MacGregor and Thatcher’s government, as did some managers in the Scottish coalfield.Footnote 146 By the end of the strike, most directors within NCB headquarters had resigned over government interference, MacGregor’s management style, and the conduct of the strike.Footnote 147

The 1984–5 miners’ strike was a particularly bitter dispute fought to prevent closures but saw mining communities divided. After the strike, the NUM was fragmented, not least after the formation of the breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM) in December 1985, based mainly in Nottinghamshire.Footnote 148 The NCB and the government exploited the disunity. In March 1985, NCB Deputy Chair Jimmy Cowan instructed managers that future closures would be imposed without consultation; a further death knell to norms and practices observed since 1947.Footnote 149 Managers attending NCB events in the aftermath of the strike were told by senior NCB officials, “[J]ust remember we won.”Footnote 150 Michael Morton, an undermanager at Point of Ayr Colliery, recalled that senior NCB officials saw it as an “opportunity to gain control of the workforce direct by management and not through the NUM,” which “those are Area level had never done themselves,” creating tensions with colliery management.Footnote 151 Among some managers there was pointed criticism of attempts to shatter the culture of prestrike industrial relations.Footnote 152

In a symbolic break with the past, the government changed the name of the NCB to the British Coal Corporation (BC) in 1987. The ensuing closures followed a familiar trajectory, the leaking of dismal press reports, a revolving door of demoralized colliery managers, and the promise of redundancy packages. Many miners carried on but others resigned themselves to their colliery ceasing production. This reflected the draining effect of the “half-life of deindustrialization,” with workforces ground down accepting redundancy payments faced by the inevitable.Footnote 153 Such was the case of Barony (Ayrshire), which finally closed in March 1989.Footnote 154 By April 1991, real unemployment figures in the Ayrshire coalfield were 30.8 percent and 36.1 percent for pit villages.Footnote 155 At Easington (Durham), BC area management reduced employment and unfounded reports appeared in the press about the colliery’s costs. In response, the NUM Lodge decided to “mount a campaign with all unions to fight any attempts to close our colliery.”Footnote 156 Their purpose was steeled by unemployment in Durham pit villages standing around 34 percent by Spring 1991.Footnote 157 Throughout 1992 into 1993 the campaign was sustained by significant public support after the government’s announcement that 31 out of Britain’s remaining 50 collieries would be closed.Footnote 158 However, with BC increasing severance payments, by March 1993, the Lodge conceded not to oppose pit closure if they could negotiate an enhanced lump sum, care and maintenance, and holiday package. In April 1993, a majority of members voted to accept the revised offer.Footnote 159 Markham Colliery, in north Derbyshire, BC employed the same tactics to run down the workforce and incentivize closure with enhanced redundancy payments between 1989 and 1993. In 1987, NUM Derbyshire Area wrote to MacGregor’s successor, Sir Robert Haslam, warning him of the effect of the mooted closure: “The employment prospects in the Chesterfield area are not good… and the associated job losses that go with a pit closure would be a devastating blow for the surrounding communities.”Footnote 160 BC announced rounds of redundancies in 1989–90 and then again in June 1992, which almost halved the workforce, despite BC Midlands and Welsh Group‘s optimistic projections for the colliery.Footnote 161 Despite a spirited NUM and NACODS-led “Save Our Pits” campaign, by 1992, what remained of the Markham workforce was worn down.Footnote 162 Markham’s new colliery manager noted of his final meetings with the unions in June 1993: “[T]he men stated that they were thankful someone had pointed out what had been obvious to them for some time.”Footnote 163 In October 1993, BC announced that all employees would be made redundant.Footnote 164 By January 1994, the villages closest to Markham, Duckmanton, and Poolsbrook, already had unemployment of 24.4 percent, well above the average for North Derbyshire.Footnote 165 In the same year, Parkside Colliery closed, preceded a year earlier by the closure of the Bickershaw Complex, marking the end of coal mining in Lancashire.Footnote 166

Collieries in the UDM’s orbit were also not immune to the risk of closure. As early as August 1986, UDM General Secretary Roy Lynk and NACODS representatives faced a standoff with Wheeler (by then Area Director for Nottingham) and his team, who were proposing a reduction of over 500 of the workforce at the Annesley-Bentinck-Newstead colliery complex.Footnote 167 Lynk and the UDM leadership, who continued to hold close meetings with the Conservative Government and Thatcher herself, expected to be afforded special favors because of their role in breaking the 1984–5 strike.Footnote 168 On 20 June 1989, Lynk wrote to Thatcher, begging for her aid and preferential treatment for UDM collieries: “It is with deep regret that I am writing this letter, but I feel it is time for your personal intervention in the whole question of the Energy Situation. In 1984 fate threw us together, and I have always comforted myself with the knowledge that the UDM has a friend in the Prime Minister.”Footnote 169 Despite Lynk’s plea, UDM-affiliated pits continued to shut between 1987 and 1994 (Table 1). Unable to persuade the government to halt this process, throughout the 1990s, the UDM became increasingly publicly critical of, and opposed to, the closure program. The most pointed example of this was the week-long stay-down protest by Lynk at Silverhill Colliery in Nottinghamshire in October 1992, and a UDM-organized march and rally in Nottingham, which proved fruitless.Footnote 170

The story of Tower Colliery, the last deep mine in South Wales, provides a sharp point of contrast with the UDM and one of the few notes of relief in the unrelenting gloom of coal’s decline in the 1990s. Tower is best known for the successful workers’ buyout in 1994, after which ran the colliery successfully from January 1995 until geological issues necessitated its eventual closure in 2008.Footnote 171 Tower implemented a model of community-oriented ownership which in some respects embodied many of the ideals of nationalization more effectively than the NCB’s centralized and bureaucratic structures.Footnote 172 Tower demonstrated well the moral contestations around closures and ownership; the buyout was a collectivist response by the colliery‘s workforce to the closure of the pit, which they viewed as a community resource, led by a NUM official, while the then Conservative Secretary of State for Wales (and ardent advocate of the liberal market reforms championed by Margaret Thatcher and then by John Major) sought to champion it as a model of entrepreneurial capitalism.Footnote 173 Less successful was the worker buyout at Monktonhall Colliery in the Scottish Lothians in 1992, with the pit closing in 1997.Footnote 174 A similar initiative had been mooted for Point of Ayr in north Wales but after significant community mobilization and a reprieve in 1992, the colliery was privatized in 1994 and closed in 1996.Footnote 175

One feature of the campaigns against colliery closures in the last nine years of nationalization was the coalescing of the three main mining unions—BACM, NACODS, and the NUM—around the defense of the nationalized industry as a collective resource and public service.Footnote 176 This was evident, for example, in the campaign to stop the announced closure of Point of Ayr. In 1990, BC’s Technical Director told Point of Ayr undermanager Morton that “the government is hell bent on destroying the industry.”Footnote 177 BACM observed in March 1991: “My how the vultures are circling.”Footnote 178 However, with the Thatcher and then Major administrations intent on contracting the industry prior to privatizing what remained, and few employment alternatives, workforces often accepted the redundancy packages placed on the table. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, unemployment in coalfield areas remained markedly higher than British averages. Hidden unemployment (predominantly those living off redundancy rather than claiming unemployment benefits) means that these figures were significantly higher, with Beatty and Fothergill calculating that by April 1991, real claimant counts among adult males (16–64) in pit villages and the coalfields respectively stood at 26.7 percent and 22.5 percent against government claimant numbers of 14 percent and 12.4 percent for both (with national unemployment figures of 10.6 percent claimant numbers and 14.9 percent for real figures).Footnote 179 With BC’s privatization, the end of Britain’s nationalized coal industry was complete.

Conclusion

In the NCB’s first edition of its Coal magazine in 1951, NUM President Sir William Lawther repeated a conversation with Ernest Bevin (Labour Foreign Secretary, and former wartime Minister of Labour and General Secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union): “you were right, Bill, when you said it would take a decade’s hard work to nationalise mining after the Act was signed.”Footnote 180 What both the NCB and miners and officials achieved within the first decade of nationalization was remarkable. However, as close observers of nationalized coal noted in its infancy, legacies from privately owned companies, complicated and centralized management structures, and diverging expectations of nationalization would present problems as they matured.Footnote 181 Crucially, the industry was subject to inconsistent policies and erratic planning, and some ministers (Labour and Conservative) were overtly hostile to the coal industry. Such endemic short-termism was not confined to coal; in 2014, the British Geological Survey’s then-science director of minerals and waste criticized the UK’s historical tendency to offshore minerals extraction and failure to pay sufficient attention to resource governance and security of supply.Footnote 182