Introduction

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered as an effective treatment for depression with rapid remission (Fink, Reference Fink2000; Spaans et al., Reference Spaans, Sienaert, Bouckaert, van den Berg, Verwijk, Kho, Stek and Kok2015). ECT has been clinically applied for decades with well documented positive benefits. Prior evidence also showed that ECT would cause cognitive impairment, especially retrograde and anterograde memory deficits (Rami-Gonzalez et al., Reference Rami-Gonzalez, Bernardo, Boget, Salamero, Gil-Verona and Junque2001). These neurocognitive side-effects, subsequently, have generally resulted in negative attitudes regarding ECT among patients with depression who may otherwise benefit from the treatment (Chakrabarti et al., Reference Chakrabarti, Grover and Rajagopal2010), although research has suggested that this is only short-lived and self-limited side effects (Semkovska and McLoughlin, Reference Semkovska and McLoughlin2010). The neural mechanism underlying the antidepressive effect and memory impairment associated with ECT, however, remains unclear (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Wang and Li2016; Nobler and Sackeim, Reference Nobler and Sackeim2008). A better understanding of these processes is needed to fine-tune ECT in order to induce less negative side effects and thus enhance the positive attitudes among patients who may benefit from it.

It is well established that the hippocampus is one of the most vital brain region involved in memory processes and is responsible for regulating emotion (Femenia et al., Reference Femenia, Gomez-Galan, Lindskog and Magara2012; Goosens, Reference Goosens2011). The aberrance of hippocampal function and structure has been implicated in emotional disorders, such as depression (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Liu, Xu, Li, Gao, Sun, Xu, Ren, Yang and Zhang2012; McKinnon et al., Reference McKinnon, Yucel, Nazarov and MacQueen2009; Small et al., Reference Small, Schobel, Buxton, Witter and Barnes2011; Tahmasian et al., Reference Tahmasian, Knight, Manoliu, Schwerthoffer, Scherr, Meng, Shao, Peters, Doll, Khazaie, Drzezga, Bauml, Zimmer, Forstl, Wohlschlager, Riedl and Sorg2013). It is worth noting that, both abnormal hippocampal function and structure could be normalized by effective antidepressant treatments, such as ECT (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Jones, Lemke, Gallegos, McClintock, Mayer, Bustillo and Calhoun2014; Dukart et al., Reference Dukart, Regen, Kherif, Colla, Bajbouj, Heuser, Frackowiak and Draganski2014; Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Espinoza, Pirnia, Shi, Wang, Ayers, Leaver, Woods and Narr2016). Although few human studies have addressed the neural underpinnings of ECT-induced memory impairment, animal model has suggested that it is closely related to altered synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Reid and Stewart, Reference Reid and Stewart1997). Taken together, these findings may indicate that the hippocampus plays a significant role in both the antidepressant effect and cognitive impairment associated with ECT.

The hippocampus has multiple subregions corresponding to different functions, including the processes of memory consolidation and emotional regulation. The hippocampus is divided into two subregions, the ventral and dorsal part in rodents, which correspond to the anterior and posterior hippocampus, respectively, in humans (Fanselow and Dong, Reference Fanselow and Dong2010; Poppenk et al., Reference Poppenk, Evensmoen, Moscovitch and Nadel2013). In humans, the posterior hippocampus (dorsal hippocampus in rodents) is primarily involved in memory function through structural connections with memory-associated regions (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter2008; Cenquizca and Swanson, Reference Cenquizca and Swanson2007). In contrast, the anterior hippocampus (the ventral hippocampus in rodents) is primarily involved in the process of regulating emotion through connections with emotion-associated structures (Cenquizca and Swanson, Reference Cenquizca and Swanson2007; Parent et al., Reference Parent, Wang, Su, Netoff and Yuan2010; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Tomic, Parkinson, Roeling, Cutter, Robbins and Everitt2007). Consistently, based on the task-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from the BrainMap database, the left hippocampus is segmented into the anterior-most emotional cluster, the middle cognitive cluster and the posterior-most perceptual cluster via the method of coactivation-based parcellation (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Barron, Kirby, Bottenhorn, Hill, Murphy, Katz, Salibi, Eickhoff and Fox2015). Indeed, dysfunction of the anterior hippocampus has been implicated in various mood disorders (Abdallah et al., Reference Abdallah, Wrocklage, Averill, Akiki, Schweinsburg, Roy, Martini, Southwick, Krystal and Scott2017; Chen and Etkin, Reference Chen and Etkin2013; Finkelmeyer et al., Reference Finkelmeyer, Nilsson, He, Stevens, Maller, Moss, Small, Gallagher, Coventry, Ferrier and McAllister-Williams2016) and while the posterior hippocampus is closely linked with memory performance in humans (Ludowig et al., Reference Ludowig, Trautner, Kurthen, Schaller, Bien, Elger and Rosburg2008; Poppenk and Moscovitch, Reference Poppenk and Moscovitch2011). In addition, both animal and human studies reported that antidepressants specifically increased anterior hippocampal neurogenesis (Boldrini et al., Reference Boldrini, Underwood, Hen, Rosoklija, Dwork, John Mann and Arango2009; Santarelli et al., Reference Santarelli, Saxe, Gross, Surget, Battaglia, Dulawa, Weisstaub, Lee, Duman, Arancio, Belzung and Hen2003) that is crucial for the success of antidepressant treatments (Sahay and Hen, Reference Sahay and Hen2007).

According to studies supporting diverse traits of hippocampal subregions and ECT-induced alterations in memory and emotion processes, we proposed that anterior-hippocampal alterations would be associated with the antidepressant effects of ECT, in contrary, the alterations in the posterior-hippocampus would be associated with cognitive impairments. In the current study, hippocampal alterations were examined with resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) based on the seed of hippocampal subregions and also by structural connectivity using probabilistic tractography to analyze interactions between functionally abnormal regions.

Materials and methods

Participants

Patients were recruited from the Anhui Mental Health Center, Hefei, China and diagnosed with depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Patients were excluded due to the following exclusion criteria: (1) a history of ECT in the last 3 months; (2) age over 65 years; (3) diagnosed with substance misuse, schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia; (4) past or current neurological illness; (5) other contraindications of MRI scan and ECT administration. A total of 53 patients completed twice MRI scans and one course of ECT. This study was approved by the Anhui Medical University Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Clinical evaluation

Patients received clinical assessments and MRI scanning both before the first ECT administration and after the last ECT administration (72 h apart). Clinical symptoms were assessed by the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and cognitive function was evaluated using the verbal fluency test (CVFT). During the CVFT, participants were required to say as many words as possible describing an animal and a vegetable within 1 min, respectively. One point was scored when participants gave a correct term for either the correct description of an animal or a vegetable. The total score was used as memory performance for further analysis.

ECT procedure

ECT procedures were conducted as previously described (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Xie, Wei, Chen, Mu, Tian and Wang2017). Briefly, pre-treatment examinations were conducted on all patients to exclude contraindications of ECT and anesthesia. Patients fasted for 8–12 h before each ECT session. ECT was administered using a Thymatron System IVY Integrated ECT Instrument (Somatics, Inc, Lake Bluff, IL) located in the Anhui Mental Health Center. All patients received ECT with bifrontal electrode placement. Six to 12 sessions were administrated three times per week. The initial percent energy was set according to the age-based method. During each ECT procedure, patients were under anesthesia with propofol, as well as the secondary medications succinylcholine and atropine.

MRI data acquisition

Resting-state and structural images of patients were acquired at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Patients were instructed to keep their eyes closed and move and think as little as possible during the MRI scan. Resting-state MRI scans were conducted under a 3.0 T MRI scanner (Signa HDxt 3.0 T, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) composed of 240 echo-planar imaging volumes with the following parameters: TR = 2000 ms; TE = 22.5 ms; flip angle = 30°; matrix size = 64 × 64, field of view = 220 × 220 mm; slice thickness = 4 mm; 33 continuous slices (one voxel = 3.4 × 3.4 × 4.6 mm). Total acquisition of resting-state MRI lasted 8 min. A T1-weighted anatomical image with 188 slices was also acquired for each patient to further elucidate and discard gross radiological alterations. (TR = 8.676 ms; TE = 3.184 ms; inversion time = 800 ms; flip angle = 8°; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2; slice thickness = 1 mm; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data were collected using spin echo single-shot echo planar imaging sequencing (repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 11 000 ms/72 ms; matrix, 256 × 256; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2; 50 contiguous axial slices with slice thickness of 3 mm) with diffusion-sensitizing gradient orientations along 64 non-collinear directions (b = 1000 s/mm2) and using three scans without diffusion weighting (b = 0 s/mm2, b0).

Functional data preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI data were preprocessed with a Microsoft Windows platform using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State Functional MR Imaging toolkit (DPARSF) (Chao-Gan and Yu-Feng, Reference Chao-Gan and Yu-Feng2010), a software package based on Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and Resting-State Functional MR Imaging Toolkit (REST; http://www.restfmri.net) (Song et al., Reference Song, Dong, Long, Li, Zuo, Zhu, He, Yan and Zang2011). The first 10 volumes were discarded to exclude the influence of unstable longitudinal magnetization. The remaining volumes were processed using the following steps: slice timing correction; realignment; normalizing the structural T1 image to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponentiated Lie algebra (DARTEL) and transferring the functional images to the MNI space based on the transformation matrix; nuisance regressors using linear detrending; 24 Friston motion parameters; white matter high signal; and cerebrospinal fluid and global signals as regressors. Subsequently, the fMRI data were smoothed with a full width at a half maximum of 4 mm. Then, the data were filtered with a temporal band-pass of 0.01-0.1 Hz. Finally, due to excessive motion (>3 mm in any of the x, y, or z directions or >3.0° in any angular motion), eight patients were ultimately excluded and 45 patients were included for further analysis.

The definition of left hippocampal subregions

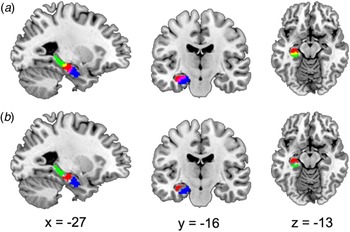

The hippocampal subregions were referred to a recent data-driven characterization that revealed a subspecialization in the hippocampus using coactivation-based parcellation (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Barron, Kirby, Bottenhorn, Hill, Murphy, Katz, Salibi, Eickhoff and Fox2015). Taken the ambiguity of right hippocampal segmentation into account in our study, only the left hippocampal subregions were selected as regions of interest (ROI). The left hippocampus was segmented into three subregions: the anterior-most subregion, involved in emotional processes (HIPe); the middle subregion, involved in cognitive processes (HIPc); and the most posterior subregion, involved in perceptual function. Noteworthy, the overlapping voxels between adjacent clusters (Fig. 1a) that may influence subsequent analysis were removed and the remaining clusters were selected as ROIs (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Sagittal, coronal, and axial views displaying the ROI. (a) Hippocampal subregions were derived from a recent data-driven study that revealed a subspecialization in the hippocampus using coactivation-based parcellation. The left hippocampus was segmented into three subregions, the HIPe (blue), the HIPc, (red), and the HIPp (green). There were overlapping areas between HIPe and HIPc (the magenta area) and overlapping areas between HIPc and HIPp (yellow). (b) After excluding overlapping areas, the remaining regions HIPe (blue), HIPc (red) and HIPp (green), were used as ROI for further analysis. ROI, region of interest; HIPe, hippocampal emotional region; HIPc, hippocampal cognitive region; HIPp, hippocampal perceptual region. These ROIs was based on the public results from the work of Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Barron, Kirby, Bottenhorn, Hill, Murphy, Katz, Salibi, Eickhoff and Fox2015) (http://anima.fz-juelich.de/).

RSFC

The RSFC was calculated using DPARSF software. For each individual, Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed between the mean time series of each ROI and the time series of each voxel in the remainder of the brain. To improve normality, correlation coefficients were converted to z-values using Fisher's r-to-z transformation and results were displayed using RSFC maps for each participant. Afterward, paired t tests were used to quantitatively compare the differences in RSFC of each ROI between pre- and post-ECT within the whole-brain mask using statistical parametric mapping. Statistical maps were then thresholded using a cluster-level family-wise error-corrected threshold of p < 0.05 (cluster-forming threshold at voxel-level p < 0.001) (Woo et al., Reference Woo, Krishnan and Wager2014) based on the SPM8 software and xjView toolbox (http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview). The BrainNet Viewer package was used to map the remaining regions onto cortical surfaces (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Wang and He2013).

Structural connectivity

DTI data of 38 patients were collected and performed in the analysis of structural connectivity. Structural connectivity was estimated for two paired regions, the left hippocampal emotional region and the left middle occipital gyrus (LMOG), as well as the left hippocampal cognitive region and the left angular gyrus, as they were ipsilateral and their respective dysfunctional connectivities were associated with clinical changes (see below). DTI data were processed using the fMRI of the Brain Software Library (FSL) (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSL). First, each diffusion-weighted volume was affine-aligned to its corresponding unweighted B0 image (b = 0 s/mm2) to correct for potential motion artifacts and eddy-current distortions. Second, fractional anisotropy was calculated by fitting the diffusion tensor model at each voxel. Finally, the probabilistic diffusion model (BED-POSTX) was used to calculate the probability distributions of fiber direction at each voxel in each individual diffusion space.

To obtain the functional ROIs in individual diffusion spaces, three steps were performed using FSL software: (a) coregister T1 to B0 image, (b) normalize T1 to the MNI space and get the inverse matrix, and (c) apply the inverse matrix to functional ROIs in the MNI space. Probabilistic tractography was then applied by sampling 5000 streamline fibers per voxel in the seed ROI. Only samples that reached cortical ROIs were retained. The properties of hippicampo-cortical fibers between the pre- and post-ECT groups were then compared at a spectrum of different thresholds (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15 of the maximal value in the tractography map) using paired t tests (threshold at p < 0.05). To illustrate the distribution of the hippocampo-cortical fibers across subjects, the tracts were normalized to the MNI space by the matrix generated by T1 normalization. Finally, all tracts were converted to a binary mask (threshold: 0.01 of the maximal value in the tractography map) and added together to produce a population-based probabilistic map (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Zhang, Xu, Zang, Liao and Lu2014).

Correlations analysis

Spearman's correlation was performed to explore associations between the altered hippocampal connectivity (functional and structural connectivity) and clinical changes (HDRS and CVFT). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with no correction. Depressive symptoms of all patients (n = 45) were assessed with HDRS, only 34 patients completed the CVFT. One patient was excluded as an outlier that exceeded three standard deviations of the mean of CVFT. Finally, 45 patients were included for subsequent correlation analysis on the changes of HDRS, and 33 patients were included for correlation analysis on the changes of CVFT.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristic

Forty-five depressed patients with an average age 38.02 ± 11.65 (17 males) were included for the final analyses. Patients showed significant improvements in depressive symptoms after a series of ECT, as demonstrated by a HDRS of 22.67 ± 4.55 (pre-ECT) compared with a mean of 5.16 ± 4.49 (post-ECT) (t = 19.27, p < 0.001). There were also significant differences in CVFT between pre-ECT and post-ECT patients (29.41 ± 9.55 for pre-ECT, 22.35 ± 8.10 for post-ECT, t = 4.08, p < 0.001).

Pre- and post-ECT contrasts with RSFC of hippocampal subregions

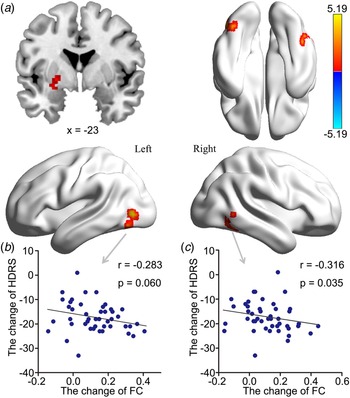

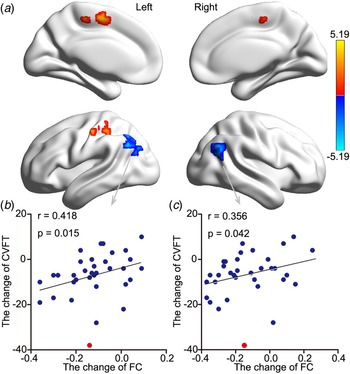

Increased HIPe connectivity with three brain areas after ECT was found: the right medial temporal gyrus (RMTG), the LMOG, and the left putamen (Fig. 2a, Table 1). Changes in HDRS were associated with changes in HIPe-LMOG RSFC at the trend level (r = −0.283, p = 0.060) and changes in HIPe-RMTG RSFC (r = −0.316, p = 0.035) (Fig. 2b and c). Decreased HIPc connectivity with two clusters after ECT was found: the right angular gyrus (RAG) and the left angular gyrus (LAG). There were two clusters that showed increased connectivity with HIPc after ECT: the left postcentral gyrus/inferior parietal lobule and the medial frontal gyrus (Fig. 3a, Table 1). A significant relationship was also found between the change in CVFT and the change in HIPc-LAG RSFC (r = 0.418, p = 0.015), as well as HIPc-RAG RSFC (r = 0.356, p = 0.042) (Fig. 3b and c). There was no significant relationship between the change of function in HIPe and the change of CVFT, or between the change of function in HIPc and the change in HDRS. No altered connectivity was identified in regards to the hippocampal perceptive subregion.

Fig. 2. The effect of ECT on RSFC of the HIPe and its relationship with clinical-symptom changes. (a) There was greater RSFC between the HIPe and the LMOG, left putamen and RMTG after ECT (Z > 3.1, p < 0.001, cluster-level FWE corrected). (b) There was a significant relationship between increased HIPe-LMOG connectivity and reduced HDRS at trend level. (c) There was a significant relationship between increased HIPe-RMTG connectivity and reduced HDRS (two-tailed, no correction). All scores were calculated using post-ECT scores subtracted from pre-ECT scores. ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; RSFC, resting-state functional connectivity; HIPe, hippocampal emotional region; LMOG, left middle occipital gyrus; RMTG, right medial temporal gyrus; FWE, family-wise error; HDRS, Hamilton Depressive Rating Scale.

Fig. 3. The effect ECT RSFC of the HIPc and its relationship with memory change. (a) There was lower RSFC between the HIPc and both the LAG and right RAG after ECT. In contrast, there was increased RSFC between the left postcentral gyrus/inferior parietal lobule and the medial frontal gyrus (Z > 3.1, p < 0.001, cluster-level FWE corrected). (b) There was a significant relationship between decreased HIPc-LAG connectivity and decreased memory performance. (c) There was a significant relationship between increased HIPc-RAG connectivity and reduced memory performance (two-tailed, no correction). Memory performance was evaluated using the CVFT. All scores were calculated using post-ECT scores subtracted from pre-ECT scores (two-tailed, no correction). The red point was regarded as singular data (defined as outside three standard deviations of the mean) and was not included in correlation analysis. ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; RSFC, resting-state functional connectivity; HIPc, hippocampal cognitive region; LAG, left angular gyrus; RAG, right angular gyrus; FWE, family-wise error; CVFT, Category Verbal Fluency Test.

Table 1. Regions showing significant differences between pre and post-ECT patients with depression

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; MNI: Montreal Neurologic Institute; HIPe: hippocampal emotional region; HIPc: hippocampal cognitive region; R: right; L: left; B: bilateral

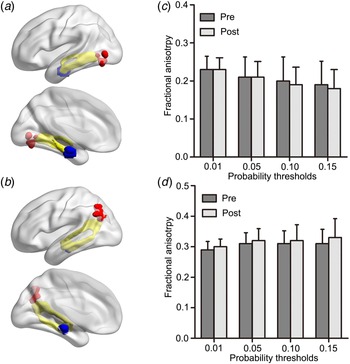

Pre- and post-ECT contrasts with structural connectivity of hippocampal subregions

Structural connectivity between HIPe-LMOG and HIPc-LAG were identified at all four thresholds. The mean image of tractography resulted in a threshold of 0.01 and is shown in the MNI space (Fig. 4a, b). There were no significant FA differences between patients pre- and post-ECT in any of the four thresholds (p > 0.05 for all, Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4. (a) Probabilistic tractography results (yellow) between the HIPe (blue) and LMOG (red), (b) as well as between the HIPc (blue) and LAG (red) are shown in the MNI space. Probabilistic maps were summed for pre-ECT and post-ECT patients and masked (threshold = 0.01). Only the voxels where more than 70% of the subjects’ data overlapped are shown. No significant differences in fractional anisotropy were found across (c) HIPe-LMOG or (d) HIPc-LAG connectivity between pre and post-ECT patients using a spectrum of probability thresholds (0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15). HIPe, hippocampal emotional region; LMOG, left middle occipital gyrus; HIPc, hippocampal cognitive region; LAG, left angular gyrus; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy.

Discussion

In the present study, we found different functional alterations in hippocampal subregions induced by ECT in patients with depression. Specifically, ECT increased connectivity in the HIPe, which may be associated with the alleviation of depressive symptoms. In contrast, ECT decreased connectivity in the HIPc, which may be related to increased cognitive impairment. Unexpectedly, ECT had no effects on the structural connectivity between the hippocampus and functionally abnormal regions, which may suggest that the effects of ECT on brain connectivity may be reversible.

Previous studies revealed a significant relationship between hippocampal functional changes and antidepressive efficacy during ECT (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Jones, Lemke, Gallegos, McClintock, Mayer, Bustillo and Calhoun2014). However, little is known regarding alterations in hippocampal subregions segmented along the posterior-to-anterior axis in depressed patients treated with ECT. The present study identified an association between altered functions in the anterior hippocampus and effective improvement. Consistent with our results, a post-mortem study on depressed patients revealed that antidepressant drugs increased anterior hippocampal neurogenesis (Boldrini et al., Reference Boldrini, Underwood, Hen, Rosoklija, Dwork, John Mann and Arango2009), that could be an important factor in the success of antidepressant treatments (Santarelli et al., Reference Santarelli, Saxe, Gross, Surget, Battaglia, Dulawa, Weisstaub, Lee, Duman, Arancio, Belzung and Hen2003). The HIPe (anterior hippocampus in previous studies) used in the present study is known to be closely correlated with functions associated with facial emotion (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Barron, Kirby, Bottenhorn, Hill, Murphy, Katz, Salibi, Eickhoff and Fox2015), and its abnormal processing is thought to be a primary clinical feature of depression (Gollan et al., Reference Gollan, Pane, McCloskey and Coccaro2008; Surguladze et al., Reference Surguladze, Young, Senior, Brebion, Travis and Phillips2004). Indeed, the abnormal neural response to facial emotions was also observed in the anterior hippocampus in previous studies on patients with depression (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Goldman, Buzas, Hodgkinson, Leibenluft, Nelson, Sankin, Pine and Ernst2010). In addition, the altered hippocampal response to affective facial expressions has been shown to be related to symptomatic improvement following antidepressant treatment (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Williams, Brammer, Suckling, Kim, Cleare, Walsh, Mitterschiffthaler, Andrew, Pich and Bullmore2007).

ECT increased the RSFC of the HIPe with the right medial/inferior temporal gyrus (including the fusiform gyrus), the LMOG (including the fusiform gyrus) and the left putamen. Increased RSFC in the medial/inferior temporal gyrus was linked to the remission of depressive severity. Interestingly, all these regions are also involved in facial emotion processing (Freiwald et al., Reference Freiwald, Duchaine and Yovel2016; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Placentino, Carletti, Landi, Allen, Surguladze, Benedetti, Abbamonte, Gasparotti, Barale, Perez, McGuire and Politi2009). Dysfunctions of the occipital gyrus, temporal gyri, and putamen have all been implicated in depressed patients and individuals at risk of depression during the task of processing facial emotion (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Norbury, Goodwin and Harmer2009; Kerestes et al., Reference Kerestes, Segreti, Pan, Phillips, Birmaher, Brent and Ladouceur2016; Surguladze et al., Reference Surguladze, Brammer, Keedwell, Giampietro, Young, Travis, Williams and Phillips2005). Based on prior evidence, as well as our results, we speculate that the alleviation of affective symptoms is associated with an improvement in processing facial emotion.

According to the meta-analysis that was used to define ROI, we speculate that the HIPc (hippocampal body) proposed in the current study is substantially involved in memory processes, including paired association recall, cued explicit recognition and encoding (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Barron, Kirby, Bottenhorn, Hill, Murphy, Katz, Salibi, Eickhoff and Fox2015). In contrast to our results, it has been shown the hippocampal posterior subregion preferentially contributes to memory function (Poppenk and Moscovitch, Reference Poppenk and Moscovitch2011). The inconsistency may result from the different segmentation of the hippocampus. Indeed, a study that divided the hippocampus into three segments showed that impaired connectivity in the hippocampal body (analogous to the HIPc in the present study) of Alzheimer's patients is positively correlated with cognitive performance (Zarei et al., Reference Zarei, Beckmann, Binnewijzend, Schoonheim, Oghabian, Sanz-Arigita, Scheltens, Matthews and Barkhof2013). In addition, the HIPc defined in the present study has previously been identified in posterior segments in most other studies (Ludowig et al., Reference Ludowig, Trautner, Kurthen, Schaller, Bien, Elger and Rosburg2008; Poppenk and Moscovitch, Reference Poppenk and Moscovitch2011). In line with the above results, our results revealed that ECT decreased RSFC between the HIPc and the bilateral AG in patients with depression, which was positively correlated with memory impairment.

The AG is a region that may have multiple functions, including semantic processing, attention, and memory retrieval (Seghier, Reference Seghier2013). Neuroimaging studies have implicated the strong connectivity between the AG and the hippocampus (Rushworth et al., Reference Rushworth, Behrens and Johansen-Berg2006; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Supekar, Amin, Rykhlevskaia, Nguyen, Greicius and Menon2010). This strong connectivity is thought to facilitate memory processing (Seghier, Reference Seghier2013; Vilberg and Rugg, Reference Vilberg and Rugg2008). Furthermore, the AG has direct connections with the parahippocampal cortex (Ranganath and Ritchey, Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012), which is strongly connected with the posterior hippocampus (Libby et al., Reference Libby, Ekstrom, Ragland and Ranganath2012). Indeed, abnormal functions associated with the AG, as well as impaired hippocampus-AG connectivity, have been found in patients with memory impairment (Damoiseaux et al., Reference Damoiseaux, Viviano, Yuan and Raz2016; Greicius et al., Reference Greicius, Srivastava, Reiss and Menon2004). For example, bilateral AG lesions resulted in an impoverished free recall of autobiographical memory and impaired memory confidence (Berryhill et al., Reference Berryhill, Phuong, Picasso, Cabeza and Olson2007; Simons et al., Reference Simons, Peers, Mazuz, Berryhill and Olson2010). Importantly, enhancement of AG-hippocampus connectivity improved memory performance in patients that underwent high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation targeting the AG (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Rogers, Gross, Ryals, Dokucu, Brandstatt, Hermiller and Voss2014). Taken together, we infer that the impaired connectivity between the hippocampus and memory-associated cerebral regions contributes to the memory impairment in depression after ECT.

It is notable that there was increased RSFC between the HIPc and the left postcentral gyrus/inferior parietal lobule and the medial frontal gyrus in depression after ECT. However, this increased connectivity was not associated with changes in depressive symptoms or memory performance. The neurocognitive mechanism involved in this result remains unclear. Given there is a prevalent comorbidity of depression and cognitive impairment (Steffens et al., Reference Steffens, Otey, Alexopoulos, Butters, Cuthbert, Ganguli, Geda, Hendrie, Krishnan, Kumar, Lopez, Lyketsos, Mast, Morris, Norton, Peavy, Petersen, Reynolds, Salloway, Welsh-Bohmer and Yesavage2006), the interactive relationship between these impairments may be one potential cause. In fact, the neural correlates of depression and cognitive impairment comorbidity have been shown to involve multiple brain regions, including the hippocampal and inferior parietal lobules (Goveas et al., Reference Goveas, Xie, Wu, Douglas Ward, Li, Franczak, Jones, Antuono, Yang and Li2011; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Goveas, Wu, Li, Chen, Franczak, Antuono, Jones, Zhang and Li2012).

Although the poorer performance of verbal fluency test following ECT has been documented in the previous study, it is more frequently treated as impairment of executive function, not memory impairment (Semkovska and McLoughlin, Reference Semkovska and McLoughlin2010). In truth, there are two classes of verbal fluency test, i.e. category verbal fluency and letter verbal fluency. Increasing evidence suggests that these two classes may depend on distinct cognitive processes underlied by different neural mechanisms. Specially, letter verbal fluency mainly reflects the executive function underlied by frontal cortex, in contrast, category verbal fluency most likely relies on medial temporal cortex (predominantly in the hippocampus), mediated the storage and retrieval of semantic knowledge (Henry and Crawford, Reference Henry and Crawford2004). Hippocampal involvement in category verbal fluency has consistently been validated functional imaging studies (Sheldon and Moscovitch, Reference Sheldon and Moscovitch2012; Whitney et al., Reference Whitney, Weis, Krings, Huber, Grossman and Kircher2009). Increasingly, CVFT is suggested as an indication of semantic memory and hippocampal function (Glikmann-Johnston et al., Reference Glikmann-Johnston, Oren, Hendler and Shapira-Lichter2015; Shapira-Lichter et al., Reference Shapira-Lichter, Oren, Jacob, Gruberger and Hendler2013). However, CVFT merely indicates the memory ability for learned information but not the new, which generally regarded as the archetypal function of the posterior hippocampus. Hence, it is without a doubt that CVFT is not the best neuropsychological assessments to test our hypothesis. Further studies are needed to replicate our study with representative assessments of hippocampal function, such as the auditory verbal learning test.

It is worth noting that a relatively lenient statistical threshold was used in our study to test for the correlations between hippocampal-connection changes and clinical variables. We conducted multiple correlations with no correction, which may potentially increase the risk of obtaining false-positive results. However, our results were acquired based on explicit prior assumptions and showed remarkable consistency with assumptions using a few of correlations analysis (three for emotional effect and four for cognitive effect). For paired ipsilateral regions (HIPe-LMOG and HIPc-LAG) which showed a significant correlation between inter-regions functional connectivity and clinical variables, impressive anatomical connectivity was also presented with DTI. These may potentially reduce the risk of drawing a conclusion based on false-positive results. Certainly, we must acknowledge that our results presented low magnitude of correlations. For example, most of the correlation coefficients just achieved statistical significance at the 0.05 level in our study and we labeled a p value >0.05 (p value = 0.06) as a ‘trend’. The low magnitude of correlations may be caused by small sample size and high between-participants heterogeneity. The seeds defined with population-level, not individual-level atlases would erode actual individual variations (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Buckner, Fox, Holt, Holmes, Stoecklein, Langs, Pan, Qian, Li, Baker, Stufflebeam, Wang, Wang, Hong and Liu2015), which may lessen the correlations between hippocampal connectivity and clinical variables. Besides, the absence of long scan duration would reduce the reliability of measuring functional connectivity (Birn et al., Reference Birn, Molloy, Patriat, Parker, Meier, Kirk, Nair, Meyerand and Prabhakaran2013; Termenon et al., Reference Termenon, Jaillard, Delon-Martin and Achard2016), which also may contribute to the low magnitude of correlation in our results. Thus, future studies are necessary to replicate our results with more large-size and homogeneous sample, longer scan duration and hippocampal seeds based on individual-level atlases.

We also admit to several additional limitations in this study. First, no healthy controls were included. Second, the sample size is too small that may have led to sampling bias. Third, twice verbal fluency tests were given and, in general, performances were evaluated after the second test. However, most patients performed worse during the second test and we believe the results of the CVFT were not biased by practice. Finally, only functional changes in the left hippocampal subregions were assessed and in future studies, it will be necessary to explore alterations in both the right and left hippocampal-subregions.

These limitations notwithstanding, our results suggest that altered functions of the HIPe may be associated with remission of depression, while altered functions of the HIPc may be associated with impaired cognition, which indicates a functional dissociation between subregions of the hippocampus.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81471117, No. 81671354, No. 81601187, No. 91432301 and No. 91732303), the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2015CB856400), the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2015BAI13B01) and Anhui Provincial Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 1808085J23).

Conflict of interest

None.