Introduction

At first glance, vagrancy might appear a marginal or somewhat anachronistic social problem in respect of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet in that period, the apparently alarming rise in the number of vagrants was a prominent topic in socio-political debates throughout Europe and beyond. How to deal with vagrancy became a central concern of early state welfare policy. Certainly, neither labour mobility nor vagrancy was a historically new phenomenon. Quite “traditional” perspectives can be found within these debates, such as the common distinction made between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. At the same time, however, a new understanding of being out of work was emerging. Historians describe this as the “invention” (or “discovery”) of “unemployment”, understood not as an individual failure, but as a structural risk of wage labour as well as a phenomenon of labour markets.Footnote 1

In this framework, some methods of searching for employment were criticized as ineffective or even dysfunctional, most of all the common practice of rambling and asking around (Umschau).Footnote 2 Public labour exchanges, by contrast, were seen as a tool for fighting unemployment and for organizing an increasingly complex national labour market. Finally, supporting and monitoring those wayfarers genuinely seeking work was intended to protect them and systematically distinguish them from vagrants and beggars who were unwilling to work.Footnote 3 A range of institutions in charge of jobless wayfarers were considered, compared, evaluated, reformulated, or newly established in different countries. The guiding principle here was “work instead of alms”,Footnote 4 but the history, organizational principles, regulations, and socio-political contexts of these institutions varied greatly. One might encounter casual wards (related to workhouses),Footnote 5 transient way stations,Footnote 6 relief stations, municipal wayfarers’ lodges,Footnote 7 wayfarers’ lodges under private auspices, hostels run by charitable associations,Footnote 8 (police) station houses, forced or free labour colonies, dépôts de mendicité,Footnote 9Herbergen, Naturalverpflegsstationen, Wanderarbeitsstätten, and so forth.Footnote 10

This paper deals with the construction of vagrancy as being the opposite of legitimate unemployment. Hence, it does not first define and then examine, but instead examines the practical making of definitions. Starting from transnational debates in the final decades of the nineteenth century, I will present a case study from Austria (more precisely the Cisleithanian part of the Habsburg Monarchy, subsequently the Republic of Austria) from the 1880s to the Anschluss.

Here, as in Switzerland and parts of Germany, a systematic form of support for unemployed wayfarers was established in the late nineteenth century – Naturalverpflegsstationen or relief stations. What was unusual was that it was regulated by provincial laws and not by charitable organizations. This attempt to establish support was closely entangled with disciplinary measures, directed toward the strict punishment or forced removal of vagrants. The continuity and/or change in the production of this social problem throughout the period and different political regimes will be addressed, from Monarchy and democracy – in which state unemployment insurance was established – to the Great Depression and the Austrofascist regime. Focusing on the interwar period, I will go on to examine the practices of the police and courts, presenting an analysis of court records. However, vagrancy or unemployment was not exclusively a problem for the government or for legislators. In order to examine the defining of vagrancy as distinct from unemployment, we have to take into account those who were on the tramp and who were regarded as vagrants or in danger of so becoming.

Transnational Debates And The Problem Of Definitions

Since the last decades of the nineteenth century, a vast amount of literature has attempted to define, describe, and differentiate vagrancy in fields such as the social sciences, social policy, legislation, criminology, psychiatry, and the like. Debates certainly did not stop at national borders and many surveys included a comparative perspective.Footnote 11 Official committees were established to study the phenomenon abroad, to compare the existing socio-political measures in different countries, and to suggest remedies for solving this problem in situ.Footnote 12 These debates focused on the same criteria and distinctions, yet “vagrancy” still remained a vague and ambiguous term.

The main features of vagrancy result from various forms of deficiency.Footnote 13 In the source material, vagrancy is commonly described as being mobile, without fixed abode or affiliation. It implies not simply drifting without a certain point of departure or destination, but also implies that one lacks the necessary means or a legitimate purpose to travel. Vagrants were not just out of work but allegedly were neither trying nor intended to find an honest living.Footnote 14 Hence, vagrancy was also often regarded as the outcome of lacking in morality or a work ethic. It was seen as an example of being unwilling to work.Footnote 15 From such a perspective, vagrancy was the opposite of what people were officially supposed to do.

At the same time, literature usually emphasized the vast heterogeneity of vagrants as well as the broad range of motivations for their activities. While adding some further aspects to the general definition of vagrancy as a deficiency, a policeman formulated this diversity in 1936 as follows:

Who doesn't know these people of the roads – a phenomenon of social hardship, coupled with an impulse to travel and a thirst for adventure? The reasons are diverse why hundreds and thousands roam erratically throughout the country. To us gendarmes they are always a pain in the neck, because their motivations are as different as the purposes and the aims of travelling people [fahrendes Volk].

The itinerant artisan, he continued, almost did not exist anymore:

Those who roam the roads today are, to a large extent, depraved people, beggars, Gypsies [Zigeuner], troublemaking ex-convicts, spies – and occasionally a free young lad who randomly wants to try out his luck in the world. There are spies, deserters, and the mostly harmless Kunde [colloquial for tramp, literally, “customer”], the real tramps. To struggle through as a genuine “honest” tramp, they need knowledge of the world, experience and an understanding of human nature.Footnote 16

Overall, vagrancy was a rather elastic term. As one writer commented, “numerous classifications […] have been made, all with a doubtful degree of precision”.Footnote 17 Some writers did not only include those who were moving continuously, but also those who roamed only at particular times or seasons and those on the move periodically with long intervals of regular life in between.Footnote 18 Vagrants travelling alone were distinguished from those travelling in groups or with their families. Vagrants might be just another type of beggar, those otherwise settled “bums”, or the homeless within cities. Definitions might go well beyond those tramps who were actually out of work. They might include those who made their living both from begging and occasional work, or those who made themselves suspicious by changing jobs frequently.Footnote 19 Itinerant trades such as hawking might also be included since they were often perceived as unproductive and merely disguising begging, in short as “negative work”.Footnote 20

Various sub-types of vagrants were described, primarily according to their degree of willingness to work but also according to their ability to work.Footnote 21 Those who were able-bodied were distinguished from the unemployable. The unemployable were grouped according to rationale. On the one hand, there were those responsible for their own unemployability as the result of alcohol abuse; on the other hand, there were those who were unemployable due to old age, illness, or injury caused by accidents or military service.Footnote 22 There were descriptions of different conditions, motives, and careers; and the potential to be reintegrated into working life differed accordingly. Besides social circumstances, other conditions of individuals or groups were named to explain vagrancy, ranging from physical and psychological to biological and racial.Footnote 23 Mentally sound vagrants were distinguished from those thought to be mentally ill.Footnote 24 Vagrancy could be seen as a result of epilepsy, lacking willpower, moral weakness, or “degeneration”.Footnote 25 Nomadism was understood as both as an example of low “civilization” and a phenomenon of modernity.Footnote 26

For all these official deficits such as lack of purpose, belonging, obligation and – by some accounts – lack of restrictions, vagrancy was nonetheless not exclusively a subject for fear, hatred, criminalization, and penalization. Often it was understood as an inevitable by-product of objective forces, circumstances, and conditions. Despite all that, vagrancy could also be seen as a personal choice, opting for a life of adventure and freedom.Footnote 27 In this regard, the vagabond has been a perennial subject for poetry, novels, and songs. Later, he became a prominent figure in the cinema.Footnote 28 Numerous autobiographies describe life on the tramp. Hence, it is inaccurate (as commonly assumed) to suggest that vagrancy was exclusively described by its opponents. As illustrated by the comments of the policeman above, such depictions could be mixed with rather contradictory elements. Legal definitions, scholarly observations, literary descriptions, and social perceptions varied in many respects. However, they are not easily distinguishable, as they often refer to each other and are closely combined.Footnote 29

The term “vagrancy” therefore seems profoundly ambiguous and somewhat arbitrary. Despite efforts to define and develop elaborate classifications, there is no coherent and consistent image, even in scholarly literature. These writings were likely not driven exclusively by the will to understand and to explain, but also – or perhaps even more – by the urge to decide on the guilt or innocence, the deserving or undeserving character of the vagrant, and the necessary measures to be taken. Making such distinctions was not just a theoretical question but a question of practical import, since it made a person subject either to assistance, treatment, disciplinary measures, or legal consequences. These attempts at definition and classification thus followed the practical logic of policy rather than science. Historians do not necessarily share these agendas. Moreover, it seems doubtful whether classification (regardless of the typology) can be useful in understanding these practices. Finally, which perspective should be the basis for such a typology? The law, the welfare system, the self-perception of the wayfarer – or perhaps the perspective of those whom he asks for help? Does neutral objectivity really suggest deciding in favour of some of these perspectives and against the others?

In the process of research, it soon becomes evident that these different practices and perspectives all contributed practically to the making of the social fact of “vagrancy” – yet each with a different level of effectiveness. Therefore, a study of the history of vagrancy cannot simply ignore the multiple, disputed meanings: vagrancy should not be defined as if it were an objectively given subject, set apart from these historical practices (including interpretation). Neither people on the move (or those in shelters, workhouses and so on) nor historians formulating their research can eliminate their involvement in the struggle over the meaning of being on the road.

The Subject Of Research

Regarding vagrants not as a given (defined in one way or the other) groupFootnote 30 with certain features, but as a product of various practices, this paper consequently does not assume an ahistorical operational definition of vagrancy. Instead, the subject of my research is the making of vagrancy in a certain historical setting. Hence, this paper addresses different contexts, practices, and perspectives that contribute to the making of vagrancy. The guiding question is how distinctions were made and instituted. Not all kinds of poverty, being out of work, or mobility were held to be vagrancy. Therefore, we cannot study this phenomenon in isolation. Nor can we understand illegitimate ways of being on the road without considering legitimate ones. Further, we cannot understand poverty and being out of work as criminal offences if we do not understand why certain of the poor were categorized as unemployed or deserving. We therefore have to contextualize vagrancy in contrast to, as well as in continuity with, legitimate ways of being on the tramp, jobless, or poor.

Research Context

With respect to the geographical area of Austria in this period, there is little research on vagrancy to build upon. Existing literature on vagrancy is focused on early modernity.Footnote 31 Research on the interwar period has been fairly focused on politics.Footnote 32 More recently, the persecution of Roma and Sinti and other travelling groups (the Jenische) during the Nazi regime as “gypsies”, “work-averse”, and “anti-social” has become a more prominent subject for study.Footnote 33 The period before the Anschluss must also be considered in this context as more than a mere prelude to National Socialist persecution. Like “vagrancy”, the term “gypsy” was quite ambiguous.Footnote 34 On the one hand, it did not refer alone to the Roma and Sinti but to all kinds of itinerant persons supposedly living like gypsies. On the other hand, it included so-called “settled gypsies”.Footnote 35 In my paper, I will focus on policies concerning those unemployed on the tramp, which in this period was often discussed differently. In fact, the term gypsy is seldom mentioned in this context.

Certainly, as pointed out before, vagrancy is not a specific problem in Austrian history or exclusively one of fascism. A broader range of research literature is available on vagrancy in other European countries and further afield.Footnote 36 In particular, there is a rich body of literature concerning tramps and hobos in the United States.Footnote 37 A more recent volume has discussed vagrancy as a European invention that became a problem on a global level.Footnote 38 We can find similar issues and discussions in countries that differ highly with regard to socioeconomic structure and institutions. At the same time, the actual policy could differ regionally to a great extent, even in the twentieth century. A systematic comparison of the actual policies in all these different countries does not lie within the scope of this paper.

Vagrancy has been discussed as a matter primarily of legal practice and law enforcement, poverty, homelessness, and welfare. Commonly, it is (exclusively) the perspective of the authorities that is being reproduced. To a lesser extent, vagrancy has been discussed in the context of migration history. And yet, the lack of clear starting points and destinations does not fit well with the traditional categories and concepts of migration research.Footnote 39 In this spirit, A.L. Beier wrote of vagrants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: “Strictly speaking, vagabonds were not migrants at all, since they were not usually making ‘a permanent or semi-permanent change of residence’ ”.Footnote 40

In several respects, this strict separation of vagrancy from “actual” migration seems highly artificial. Vagrancy might be not only a form of internal but also international mobility. It could be labour migration or perhaps only subsistence mobility. This, however, could also change throughout a person's journey. Migration history usually classifies migrants according to their official status as labour migrants or refugees, without considering the personal viewpoint of the migrant.Footnote 41 Owing to a focus on permanent and border-crossing transnational or transcontinental movements, internal migration has conventionally been neglected within research, being seen as less significant and more or less unrestricted.Footnote 42 However, more recent research has indicated that migration is generally not a direct one-way movement from one location to another but rather a series of movements between places.Footnote 43 Hence, there might often not be an obvious starting point or destination.

Moreover, the actual purpose and meaning of mobility is at issue, not only with respect to vagrancy but also in many other cases such as the free or forced character of migration.Footnote 44 Seen in broader historical perspective, migration controls have not solely targeted international migration. On the contrary, the “floating population” of the travelling poor had been a concern of policy long before modern states started to establish national migration controls.Footnote 45 John Torpey and Gérard Noiriel have pointed out that as modern states have expanded their administrative capacity to embrace those populations residing under their jurisdictions, regulations concerning internal movements (and residency) have at times been enhanced as well.Footnote 46 The persistence of vagrancy as a social problem indicates that internal mobility, even in the twentieth century, was not totally unregulated. Rather, it was still restricted; especially for the poor.Footnote 47 The paper will illustrate this point in respect of the Habsburg Monarchy and Austria.

Vagrants have a similarly awkward position within the history of labour. Labour history – particularly in the German-speaking world – was traditionally focused on what was considered as “the core” of the working class: workers in modern industries. The so-called Lumpenproletariat or “underclass” was seen as a discrete entity and more or less neglected. More recent writings, however, particularly those inspired by global labour history, have pointed out that this notion of the working class was rather fictional.Footnote 48 In fact, the distinctions between labourers, farmers, peddlers, beggars, vagrants, and the like were often blurred. Patchwork lives and patchwork incomes – a “makeshift economy”Footnote 49 – can be viewed as fairly common, or even more, the rule than the exception. Yet “makeshift” or the attribute “precarious” make sense only in contrast to the dominant notions of a decent livelihood and regular wage employment that were emerging in the framework of the welfare state. It was not only work that was normalized and institutionalized during this process, but also certain forms of non-work such as unemployment in contrast to vagrancy.

Vagrancy and The “Invention” Of Unemployment

Although the state perspective on this form of mobility is not sufficient to understand it, there is certainly no way to ignore the official definitions of vagrancy made by government, legislature and the police. Legal definitions can have a significant – but not an automatically given – efficacy.

Similar to other European states, the Habsburg Monarchy enacted a new vagrancy law in the late nineteenth century. The statutory basis for defining and dealing with vagrancy in the courts (a foundation which remained in force in the interwar period and even in post-World War II Austria) was an 1885 lawFootnote 50 that replaced the Vagrancy Act of 1873.Footnote 51 According to Section 1 of this law, a person who wandered about without business or employment and who was unable to prove that he or she had a livelihood or was trying to earn one honestly, was to be penalized for vagrancy. Hence, mere homelessness was not a sufficient criterion. Section 2 of the law concerned begging “in public places or from house to house or to claim public charity due to an aversion to work”. Further, the law required proof of earning a livelihood in a permitted fashion from any person able to work but without legal income, or from a person who appeared dangerous to the security of persons or property. Communities were entitled to assign appropriate labour to a person able to work but without means. Refusal to accept the occupation could be punished by arrest. Lastly, the law addressed the occurrence of women who conducted “immoral business with their bodies”. The penalty for such acts was imprisonment and/or admission to an institution for forced labour. Altogether, the law defined a complex of activities regarded as contrary to honest work, and not solely mobility without means of subsistence. These activities were defined as legal and economic problems. Begging was an illegitimate request for support without offering an adequate service in return, and vagrancy was seen as a form of travel without a redeeming economic benefit. It was neither tourism nor business, and it revealed no indication of the only recognised activity for unemployed people without means: the search for legal employment.

Shortly after enacting this law, however, a systematic attempt to provide help for unemployed wayfarers was made. Between 1886 and 1892, seven provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy (specifically, in Cisleithania) established Naturalverpflegsstationen Footnote 52 (translated by contemporaries as “relief stations”Footnote 53 or “stations of help”Footnote 54) that would provide food and shelter for wayfarers in search of employment. The organization of these stations followed explicitly the early model of similar institutions in Switzerland, the Netherlands and parts of the German Reich (specifically, in the state of Württemberg).Footnote 55 Such relief stations were regulated by provincial laws and decrees. Run by municipalities, they were in turn financed by districts and supervised by provincial governments. These relief stations were thus the subject of public governance and not of charitable religious organizations as in other countries.Footnote 56

According to the regulations, the Naturalverpflegsstationen were open to all unemployed, able-bodied wayfarers without money or subsistence, irrespective of their gender, religion, or the place where they had a right of residence. In this way, the relief provided tended to be detached from a particular occupation or membership of a trade association or union.Footnote 57 (By contrast, the houses of the Kolpingverein, the Catholic journeymen's association, were open only to members, mostly journeymen and/or skilled labourers). Nevertheless, some provinces excluded certain occupations.Footnote 58 To be admitted, a person had to confirm his or her identity and that he or she had been employed in some manner in recent months.Footnote 59 Exactly how long a wayfarer could use the relief stations while travelling was subject to limitations (varying from six weeks to three months in different provinces).

According to the statutes, wayfarers were required to perform a “work test”: some hours of “appropriate” work to prove their willingness to work in exchange for meals and lodging.Footnote 60 The relief stations were also regarded as a first step toward establishing public employment exchanges, as they were required to keep a list of opportunities for employment.Footnote 61 In contrast to workmen's colonies or workhouses, visitors were kept on the move: a stay in a Naturalverpflegsstation was restricted to 18 hours and returning to the same relief station within one period of wandering was not permitted except in exceptional cases. Evidently, the intention was to urge the unemployed to workFootnote 62 in a regulated manner, proceeding from station to station; relief stations were supposed to be within a distance of approximately 15 km of each other. At the turn of the century, 814 Naturalverpflegsstationen existed in the Habsburg provinces. It is difficult to conclude how many wayfarers actually made use of these stations based on the available numbers for arrivals (see Table 1). Contemporaries estimated that on average a single wayfarer made use of 10 to 12 stations during his or her journey. In interpreting these numbers, we must keep in mind that they do not represent all the wayfarers on the road, as many of them did not find or seek admission to the Naturalverpflegsstationen.Footnote 63

Table 1 Naturalverpflegsstationen in Cisleithania

Source: Arbeitsvermittlung, pp. 112–117.

The primary purpose of these institutions was explicitly to fight vagrancy. Yet apparently they did not intend to stop labour mobility in general. Rather, they aimed to organize and regulate mobility, while institutionally separating those genuinely seeking employment from those vagrants assumed to be habitually averse to work.Footnote 64 According to the official standpoint, providing rational assistance to wayfarers should replace the irrational giving of alms.Footnote 65 Doing so would protect the health and morality of wayfarers while also reducing their potential for humiliation.Footnote 66 At the same time, these measures were intended to allow more intense and efficient penalizing of vagrants – those supposedly outside the system – and help to reduce the costs of Schubwesen.Footnote 67 This had been long practised but was also newly regulated at that time by a law of 1871.Footnote 68 It meant the possibility of forced removals: the deportation of foreigners or citizens to the community where they had a Heimatrecht. The Heimatrecht – a permanent right of residency – implied that a community had the responsibility to care for its impoverished members. In the case of crime or poverty, a citizen could be sent back to his or her official home town. And further, to return to the site of forced removal was a punishable offence. Such laws, then, stood in striking contrast to those citizens granted more general liberty to move or settle. The crucial point was that a Heimatrecht was acquired by birth (through the father or single mother), by marriage or by acceptance of the community.Footnote 69 Particularly in the late nineteenth century, a Heimatrecht quite often differed from a person's actual place of residence. At that time, upwards of 80 per cent of citizens within larger cities had their Heimatrecht elsewhere.Footnote 70 Whereas the efficiency of Naturalverpflegsstationen with regard to job placement was sometimes doubted, many contemporary observers acknowledged that convictions for vagrancy significantly decreased after the relief stations had been established, a reason that they were regarded as a thorough success.Footnote 71

The struggle against vagrancy was therefore embedded in a complex of social and political concerns, including domestic security, labour market organization and the regulation of (national) mobility. The Naturalverpflegsstationen were a first step in constructing and formalizing the category of unemployment as distinct to that of vagrancy. They represented an emerging state social policy that turned out to be more systematic than ever before. As of the late nineteenth century, a number of laws had been established regarding not only unemployment but also labour relations and insurance in case of disability, illness or retirement (first for civil servants, then for other citizens). The fight against vagrancy did not at all contradict this social policy, which has been described as the launch of state welfare policy.Footnote 72 This understanding of the right to work in that era as well as the provisions made for legitimate forms of non-employment necessarily required the state to penalize illegitimate non-work. In this sense, Karl Wilmanns wrote in a book on vagrancy:

The more the state and public welfare are engaged for those unemployed through no fault of their own – that is, for the physically and mentally adequate worker, who has become unemployed because of age, illness, crises or a bad business climate – the more it appears inevitable to take the welfare away from such inferior elements, from those who just work every now and then or not at all, and most of the time or permanently live from others’ relief. They should be cared for in other ways permanently or for an undetermined time. This is the absolute precondition for public welfare to thrive in the case of the fully-fledged unemployed.Footnote 73

Work, as another author stated, was the foundation of the modern social state. Everyone who did not work was a threat to the community (Gemeinschaft): “Whoever abandons themself to an idle and lazy life – if he is able-bodied – violates basic social law and behaves anti-socially by exploiting private welfare or the right of existence granted by public welfare”.Footnote 74 Hence, the policy concerning vagrancy was just the flip side of the coin of the new state welfare policy.

Nevertheless, not every way of making a living was acknowledged equally as a form of work.Footnote 75 Not every occupation included the possibility of becoming “unemployed”. The formalization of unemployment, as Bénédicte ZimmermannFootnote 76 has described it in the case of Germany, was closely bound to certain notions of Beruf (vocation) and often excluded unskilled work. In case of the people registered at Naturalverpflegsstationen, we can see that it was almost exclusively men who sought or found admission and that a very high percentage of the registered were craftsmen and skilled workers. A survey from the turn of the century reveals a share of almost 70 per cent craftsmen among the wayfarers arriving at relief stations in Lower Austria in 1899.Footnote 77 In Moravia in 1895, 76 per cent of all wayfarers using Naturalverpflegsstationen were registered as skilled labourers (Professionisten).Footnote 78 These high numbers of craftsmen reflect the specifics of industrialization in central Europe. As Josef Ehmer has pointed out:

The peculiarities of central Europe can be seen in this fact that master artisan's workshops kept their dominant position as places and units of production. […] The circulation of single, living-in journeymen between and within the large cities such as Vienna created a highly flexible trans-regional labour market and served to maintain a balance between labour demand and labour supply, as it had done for centuries. As it seems, the old journeymen's tramping system fitted perfectly to the new economic environment.Footnote 79

Journeymen did not only contribute significantly to the high mobility at the turn of the century; they also clearly characterized the image of unemployed wayfarers in central Europe. Long after the abolition of guilds, the tramping artisan was the model of orderly travellingFootnote 80 in contrast to the vagrant. Within the crafts, tramping was an established method of finding employment and gaining professional experience. Being out of work was formalized in many respects – long before the general formalization of unemployment. Even before Naturalverpflegsstationen were instituted, travelling artisans could rely on mutual support from master artisans, colleagues, or trade associations. Such practices seemed to fit with the emerging new concept of “legitimate unemployment”. Yet the discussions on vagrancy also frequently evoked how this “tradition” was coming to an end.Footnote 81 The wandering journeyman or labourer was therefore seen as constantly in danger of becoming a vagrant due to insufficient support or integration into a guild.Footnote 82 This permanent reference to artisanal tramping (and not just labour mobility) seemed to form an important difference to other countries. Instead, Anglophone research on vagrancy and on American tramps and hobos focuses on unskilled labourers seeking seasonal or occasional employment in harvesting, construction, and the like.Footnote 83

After World War I

A real boom in legislation accompanied by a new type of state policy went along with World War I, and even more with the founding of the new democratic state of “German Austria” (1918), renamed the “Republic of Austria” (1919) in the aftermath of the war. Unemployment benefits were established in 1918 and unemployment insurance in 1920, together with public labour exchanges. The Industrielle Bezirkskommission, a commission consisting equally of employers’ and employees’ representatives, was assigned the tasks of registering the unemployed, finding jobs for war returnees, fighting joblessness, and arranging unemployment benefits.Footnote 84 In addition, several new regulations were introduced, aimed at intervening in labour relations, working hours, holidays, occupational training, and so on.

Such social policies attempted to stabilize the fragile new state, which – like many other European countries – struggled throughout the interwar period with political instability and severe economic crises. But state social policy had a limited impact in those years. Many people did not obtain access to these new forms of social security. Furthermore, these forms also varied regionally, ranging from “Red Vienna” with a highly systematic modern welfare system, to more rural areas.Footnote 85 Unemployment insurance, for example, never included all labourers and occupations equally.Footnote 86 Soon after unemployment assistance was more generally established, a number of exceptions were made for people living in mostly rural areas, farm labourers, domestic servants, the young, and self-employed persons.Footnote 87 Support was predicated upon willingness to work and to accept “appropriate” occupations and assistance was granted only for a restricted period.

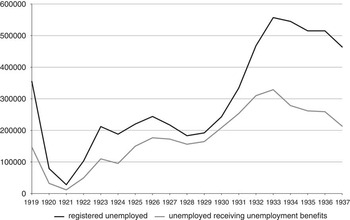

With the exception of a few years immediately after World War I, Austria had an extraordinarily high rate of structural unemployment. During the world economic crisis, the unemployment rate rose drastically and officially reached 25 per cent of the workforce; some historians estimate it was as high as 37 per cent in 1934. Many unemployed lost their unemployment benefits, having to rely on Notstandsunterstützung (crisis benefits), poor relief or other sources. The percentage of unemployed receiving benefits declined to 50 per cent in 1937, at a time when the estimated unemployment rate was between 21.7 per cent and 31.8 per centFootnote 88 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The relationship between the absolute numbers of unemployed officially registered and those receiving benefits.Source: Stiefel, Arbeitslosigkeit, p. 29.

Neither tramping in search of work nor vagrancy disappeared within this period. The new social policies did not fully displace poor relief and related legislation (the Heimatrecht, the Vagrancy Law, and the Schub). Naturalverpflegsstationen (now dubbed Herbergen, or “hostels”) were re-established in most federal provinces of the Austrian Republic as of the 1920s.Footnote 89 (In Vienna, an asylum and voluntary workhouse for the homeless was designated to serve the same function). As a matter of principle, the unemployed on the tramp were not supposed to receive money but rather assistance in form of food and/or lodging.

Whereas unemployment benefits and similar policies (such as housing programmes) enabled people to stay in one place,Footnote 90 support by relief stations enabled them to move around. Yet this form of welfare was also restricted. Women, already a diminishing minority at relief stations, were now explicitly excluded from them in several federal provinces, as were wayfarers with financial means and those who were unemployable because of age or physical disability. In order to obtain the requisite Wanderbuch (“wayfarers’ pass”Footnote 91 or “travellers’ relief book”Footnote 92), citizens had to prove they had been employed for at least four weeks within the previous six months. Access to relief stations was restricted in most provinces to periods of about four months per person. As in the era of the Habsburg Monarchy, Herbergen were usually combined with Schubstationen (basically, detention cells for forceful removals). In comparison with the era of the Monarchy, the principles guiding relief stations remained more or less the same.Footnote 93

However, this new context may be seen as contributing to a redefinition of more traditional ways of finding employment through mobility.Footnote 94 Relief stations were now a secondary form of support for the unemployed, especially those who had lost (or who never had) the right to unemployment benefits.Footnote 95 The tramping unemployed were sometimes referred to in discussions as the “second-class” unemployed. The new character of tramping was frequently condemned, and the definitive end of journeymen's traditional tramping was proclaimed once again. “The former journeymen's tramping”, as one journalist claimed, “has finally died. It does not make sense to knock on a door, searching for work at a master craftsman's, when that master craftsman has no work and in many cases is himself unemployed”.Footnote 96

It is difficult to estimate how many people made use of these institutions during this period. There are no centralized statistics, and evidence is scattered. The number of visitors evidently varied from town to town (see Figure 3). But as a general tendency, visitor numbers on the whole were in decline from the first years of the century. During the war, many Herbergen were used for other purposes, and in the remaining stations the number of visitors was very low. In the aftermath of the war, the figures increased again only very slowly. Admittedly, this finding is roughly consistent with the general decline in mobility rates for the epoch, as described by historians.Footnote 97

Figure 2 1925 outline map of Herbergen in Upper Austria, showing the locations of Herbergen and the distances between them.Source: Landesarchiv Salzburg, Marktarchiv Werfen, Kt31, Fremden-Herbergs-Akten Werfen 1927–1938. Used with permission.

Figure 3 Visitors per year at municipal Herbergen (in Upper Austria and Salzburg) and at the printers’ Herberge in Vienna.Source: Stadtarchiv Wels, Akten, Karton 2131, Akten Registraturordnung III J-c Naturalverpflegsstation, Rechnungen 1904–1924; HM Hauptverwaltung – Militär und Meldewesen, Karton 2669, Naturalverpflegsstation Wels 1919–1940; Stadtarchiv Linz, Materienbestand Mat. 54 1908–1928, Karton 609, Herbergen; Salzburger Landesarchiv, Marktarchiv Werfen, Karton 31, Faszikel Herberge, Kassabelege erledigt; 1904–1929. 25 Jahre Wiener Buchdruckerherberge. Zusammengestellt und herausgegeben von der Herbergsgruppe des Reichsvereines der österreichischen Buchdruckerei- und Zeitungsarbeiter, Verantwortlich Josef Matik (Vienna, 1929), p. 31.

Several factors resulted in less mobility in the years before and after World War I. In addition to political, socioeconomic, and demographic changes, migrants were encountering new border and migration controls. However, with the onset of the world economic crisis, the number of people on the tramp significantly rose once more. As can be concluded from the registers of various Herbergen (see Figure 3), such estimates depend more on the location – and less on the size – of the city involved. The statistics from one public Herberge in the small town of Werfen (located on an Alpine route in the province of Salzburg) indicate quite a high frequency of visitors. The Herberge was established in November 1928, and although there were up to 10,000 visitors registered a year, the town itself had only 2,105 inhabitants in 1934.Footnote 98

Not only did the number of wayfarers change, but their registered occupations as well. Fewer craftsmen and skilled workers used relief stations after World War I even though the number of small workshops (often with so-called “traditional” labour relations) remained high in Austria between the wars. In the relief station registries for the town of Wels in 1924, skilled workers and craftsmen comprised only about one-half of the visitors.Footnote 99 In the Herberge in Werfen (Salzburg),Footnote 100Hilfsarbeiter (unskilled labourers) made up 42 per cent of all registered occupations. The remaining entries, representing a broad range of different occupations, consist of about 40 per cent craftsmen and skilled labourers. Still, there is no way to determine on the actual work of the wayfarers. Similar proportions of skilled to unskilled workers can be found in statistics on wayfarers in German regions.Footnote 101 Consequently, despite the decline in journeymen turning to the Herbergen, their tramping was not yet at its end.

As the world economic crisis continued, however, the numbers of visitors to these Herbergen decreased. This decline was obviously not related to a lesser demand for support. After all, the difference between those registered as unemployed and those receiving support was quite high in those years (see Figure 1). Rather, the decline was due to tougher restrictions on access as well as the rising number of long-term unemployed who could not even provide proof of recent employment, a requirement for using the Herbergen in the first place. In Lower Austria, for example, 125 Herbergen existed.Footnote 102 Most of them provided about 12 to 15 beds, accommodating up to 30 people a day and, according to reports, approximately 2,000 visitors a year.Footnote 103 In the 1930s, officials at the Herbergen complained that the number of wayfarers far exceeded capacity.Footnote 104 Some towns provided makeshift accommodation or permitted wayfarers to sleep in detention cells. Finding food and shelter in a Herberge thus depended on the (financial) ability and willingness of the local community to support even those wanderers without entitlement.

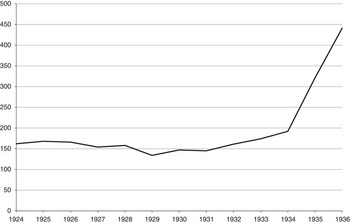

Vagrancy and the tramping unemployed – concern over whom had been displaced in political debates by the question of unemployment insurance – again became a prominent focus for controversy. In the 1920s, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Internal Affairs had regarded the problem of vagrancy as solved.Footnote 105 Yet during the world economic crisis, and especially in the period of the Austrofascist regime (1933–1938), a “plague of beggars and vagrants” again became an urgent problem for internal security and social policy. The Department of Internal Affairs of the Federal Chancellor estimated the number of vagrants at 17,000 in the mid-1930s.Footnote 106 The crime statistics (available from 1924 to 1936) also show a drastic increase in sentences on the basis of the Vagrancy Law (see Figure 4). In 1935, there were in absolute numbers 15,827 convictions; in 1936, there were 21,752.Footnote 107

Figure 4 Convictions on the basis of the Vagrancy Law of 24 May 1885 per 100,000 persons of the age of criminal responsibility (in the territory of Austria).Source: Zahlenmäßige Darstellung der Rechtspflege, 5 (1926), p. 7; 7 (1927), p. 5; 10 (1929), p. 5; 12 (1929), p. 7; 14 (1930), p. 8; 16 (1932), p. 7; 18 (1932), p. 6; 20 (1933), p. 6; 24 (1935), p. 9; 28 (1936), p. 8.

Austrofascism

The Great Depression, and even more the establishment of an authoritarian regime, signalled in many ways a turning point in policymaking on vagrancy. Austria, like other European countries, was characterized by political instability throughout the period. After World War I many doubted if Austria, now much smaller than and separated from the other countries of the former Habsburg Empire, could economically survive. The country had been split since the 1920s between “Red Vienna”, governed by the social democrats, and the remaining provinces, which were politically conservative. Both the Social Democratic Party and the Christian Social Party had their own paramilitary groups involved in violent conflicts, particularly after 1927 and later in the Civil War of 1934. Within the Christian Social Party and their paramilitary organization (the Heimwehr), the latent tendency towards an authoritarian regime became manifest in the Korneuburger Eid (Oath of Korneuburg) of 1930, which expressed their opposition to a democratic regime. The National Socialists were gaining ground, too.

In the elections of 1932, when the conservative block was eroding and its majority in Parliament was endangered, the tendency towards an authoritarian regime became even more obvious. In 1933 parliamentarian democracy was abolished (the so-called “self-elimination of the Parliament” due to procedural challenges) and the so-called Ständestaat was established under the leadership of the Christian Social chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss. This Austrofascist regime was oriented on Italian fascism and sought an alliance with Mussolini in an attempt to retain its independence from Nazi Germany. The Vaterländische Front (Fatherland's Front) was created with the aim of uniting all political forces loyal to the new regime. The Social Democratic Party, the Communist Party, and the National Socialist Party were forbidden, and their members persecuted and imprisoned. However, Dollfuss was murdered in the Nazi coup attempt in 1934, and his successor Kurt Schuschnigg signed an agreement with the Third Reich in 1936. Imprisoned National Socialists were then freed and members of their party included in the cabinet.

The historiography of interwar Austria usually focuses on the developments leading to the Anschluss in March 1938 and on the question of political responsibility, the Austrofascist regime having been regarded by some as an attempt to retain independence from the German Reich by authoritarian means. Historians have tended to concentrate on political decisions as well as the regime's persecution of opponents and manifest anti-Semitism. Yet very little research has been done on the persecution of “anti-socials” (Asoziale) within this context or the general social history of this era.Footnote 108

Certainly, as described above, the persecution of beggars and vagrants was not invented in this context but earlier. Imposing imprisonment and forced labour on those convicted for begging and vagrancy was not solely linked to a conservative or fascist ideology. In addition, within “Red Vienna”, police raids were made to arrest beggars.Footnote 109 Julius Tandler, the city councillor for social policy, had little favourable to say of the Lumpenproletariat.Footnote 110 He regarded begging as unnecessary, harmful, and in striking contrast to rational welfare. The Austrofascist regime, however, did not only intensify penalization; it also marked a turning point in social policies. As pointed out before, the economic crisis led to a dramatic rise in unemployment. At the same time, the regime drastically restricted or abolished social rights such as unemployment insurance and also assistance for the unemployed wayfarer.

Unlike unemployment benefits, which were the responsibility of the Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, the Herbergen as a form of poor relief remained the responsibility of local communities and provincial governments. These were still bound to principles of Heimatrecht (as of 1863) and subsidiarity.Footnote 111 Although several reforms of this law after 1863 ultimately made it easier to acquire a Heimatrecht, it remained unchanged with respect to social welfare, something crucial for people on the move seeking assistance in other communities. Since a person's home town could be charged for any assistance provided by other towns, the tramping unemployed were a source of ongoing conflict between provincial governments. Some municipalities were accused of supporting such payments for the poor (in order to actually make money from them), contrary to the will of their communities. Since compensation for the expenses did not work, some communities also relieved their costs by sending their unemployed back out on the road.

This system evidently required a significant bureaucratic effort; thus, the question of the tramping unemployed finally brought this system of responsibilities up against its limits. A reform of the Heimatrecht was discussed as a key issue in solving the problem of vagrancy in a series of four conferences held by provincial governments between 1935 and 1936.Footnote 112 In its wake, however, social support for the wanderers was only partly disconnected from the Heimatrecht in 1935. Assistance was to be kept as low as possible in order to discourage wandering. In addition, tighter regulations for entitlement were established. Asking for assistance outside one's home town without a Wanderbuch or an Unterstützungsausweis (“support identification card”) was punishable by arrest. The aim was “to separate the wheat from the chaff”, those unwilling to work from the unemployed truly searching for a job.Footnote 113 The fight against vagrancy was intensified by instituting these additional measures.Footnote 114

As mentioned before, the Vagrancy Act of 1885 already allowed those convicted under it to be assigned to an institution for forced labour (Zwangsarbeitsanstalt) for up to three years – after judgment by the court and having served the actual sentence.Footnote 115 Release depended on whether the convict made discernable improvements.Footnote 116 In the 1930s, additional legal options were instituted in order to keep small-time criminals and people “with an engrained aversion to honest moral conduct and labour” under arrest at an Arbeitshaus (forced labour institute) for up to five years.Footnote 117 These drastic measures, however, represented the most extreme ways of handling the (deviant) poor. According to complaints by criminologists at the time, they were not implemented often enough in practice.Footnote 118

At the beginning of the world economic crisis, the police had complained they were powerless, and due to widespread poverty, the law could not be rigorously enforced.Footnote 119 Now, in the Austrofascist regime, a series of countrywide police raids were conducted against beggars and vagrants. Labour camps were discussed as a particularly attractive alternative. Some politicians estimated a requirement for 1,000 people in Vienna and 500 in the other provinces.Footnote 120 However, based on a police raid in a district of Lower Austria, during which reportedly 5,000 people were arrested, a politician cited the potential need for 10,000 places for beggars and vagrants for this federal province alone.Footnote 121 Yet, due to the expenses necessary, most of the provincial governments refused to set up labour camps. Forcing vagrants to work in such a way in a period of mass unemployment was also rejected because, it was argued, the rare jobs that could be created should be reserved for unemployed Austrians actually willing to work and should not be wasted on vagrants and those unwilling to work.

Thus, the Bettlerbeschäftigungsanstalt (Institute for Beggars) established by the Viennese government in 1935 explicitly aimed to end the idleness of beggars. Yet, at least according to official statements, it avoided giving them “real” work with any impact on the national economy and labour markets.Footnote 122 By contrast, the Upper Austrian government proudly introduced a labour camp in the same year.Footnote 123 The inmates rounded up during countrywide raids upon vagrants had to build streets or shovel earth at archaeological sites. The cost and effectiveness of this institution were disputed, nonetheless. The raids did not reduce vagrancy but instead, as other provincial governments complained, drove the vagrants to other provinces with less stringent policies. The labour camps also did not enable the unemployed to be reintegrated. After they were released from camps, former inmates still had no jobs. Many of them were simply provided with a travellers’ relief book and sent out on the road again.

Crime Statistics and Court Cases

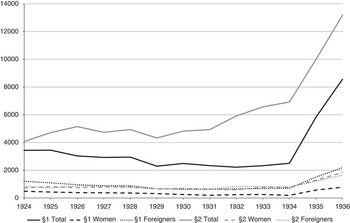

Who was convicted for vagrancy? According to the crime statistics between 1924 and 1936, the vast majority of convictions under the Vagrancy Act involved begging, followed by vagrancy (see Figure 5, overleaf). Whereas convictions for begging increased throughout this period, judgements against vagrants declined under democratic regimes (though they rose rather drastically from 1934 onwards). Those convicted for offences under the Vagrancy Act were most often men.Footnote 124 The statistical share of women convicted for vagrancy ranged only between 8 and 14 per cent, a proportion that fell even during the world economic crisis. With regard to begging, the share of women convicted ranged between 10 and 18 per cent. This might have been an effect of gender-specific perceptions of poverty or welfare, or of selective punishment. But it might also have reflected different strategies and options for dealing with poverty. Despite a tendency to displace women from the labour market after World War I had ended, it could be still easier for women to seek some employment – no matter how precarious – in a household or within a low-wage sector,Footnote 125 for their labour was less bound to a particular occupation.Footnote 126 Welfare institutions for unemployed wayfarers open only to men probably made tramping seem a less viable strategy for unemployed women than it was for men. Lastly, according to the statistics, about one-third of those convicted were foreigners. The proportion of women was even lower among foreigners than among convicts with Austrian citizenship.

Figure 5 Convictions on the basis of §1 (vagrancy) and §2 (begging) of the Vagrancy Law of 24 May 1885 in absolute numbers (for the territory of Austria).Source: Zahlenmäßige Darstellung der Rechtspflege, 5 (1926), p. 7; 7 (1927), p. 5; 10 (1929), p. 5; 12 (1929), p. 7; 14 (1930), p. 8; 16 (1932), p. 7; 18 (1932), p. 6; 20 (1933), p. 6; 24 (1935), p. 9; 28 (1936), p. 8.

Court records give further insights into police procedures and court decisions; however, they are preserved only very selectively and randomly. I will make some conclusions based on a sample of 800 court records from various court districts in the period from 1918 to 1938.Footnote 127 Analogous to the crime statistics, begging was the main accusation in these records; only 40 per cent were additionally accused of vagrancy. Evidently, both crimes were closely related. Vagrancy was not exclusively concluded to result from mobility, since 59 per cent of those arrested were described by the police as “unstet” (“wandering” or “unsettled”). By definition, vagrancy took place within the countryside and indicated how drifting had endured. Further crimes might be included in the accusations, such as minor theft, defamation of a civil servant on duty, malicious damage, illegal reversal after being banished, and so forth. Of all those arrested, 80 per cent were between the ages of 18 and 50 and the proportion of unmarried, divorced or widowed persons (only 19 per cent were married) was considerably higher in this age group than for other citizens. The religious denomination of the arrested corresponds fairly well with the religious denominations of the population at that time: 90 per cent were Catholics, and only a few were Jewish, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox, or Muslim.Footnote 128

The overall conviction rates varied greatly between provinces: Vienna had the lowest rate of convictions, Vorarlberg and Upper Austria the highest with respect to the adult population. Moreover, significant variations were also found within the provinces and even between police districts. Differences can be found between the court districts according to the age, marital status and occupation of the convicts and the legal procedure. Some court districts such as Wildshut preferred to deal with settled beggars instead of vagrancy. There, a high proportion of the records involve unemployed, unskilled workers (Hilfsarbeiter) from the neighbouring districts where industry had declined during the economic crisis. The share of married convicts and women was higher in comparison to the overall average of the sample. In trials of settled beggars, a greater effort was made to verify identity, crime records, the circumstances of the offender, and his or her defence. In the process of these inspections, necessity was sometimes acknowledged as a reason to drop the charges. Other districts such as Mondsee had a higher share of skilled workers and craftsmen passing through. The average age was lower here and the proportion of unmarried persons higher. The accusation of begging was more often combined with that of vagrancy, and little effort was expended on the (conventionally) speedy trial.

Most commonly, the arrested had only a certificate of their Heimatrecht, a document without a photo substantiating their right of residency. A few merely had passports and several had no documents at all. Fingerprints were taken from about 9 per cent in order to identify and register them. Among the accused there were also cases of some who had been drifting through Europe for many years, having been banned from several countries. Astonishingly, only twelve persons in this sample were described as Zigeuner (gypsies), usually entered as “occupation”. A regional bias of the source material might also account for this circumstance. Itinerant occupations like peddling were also rarely mentioned. Some beggars, though, illegally traded postcards, spices, or food they received as alms. Some engaged in busking. More or less all of those arrested, nonetheless, were without regular employment. Yet some stated that they worked occasionally on farms in exchange for food, or that they had previously worked, even though most of them could not provide documentation of recent employment or having applied for jobs. Many had apparently been out of work for a long period of time and stated that they could not find a position or that there were simply no possibilities.

Whereas the settled beggars sometimes received unemployment benefits or poor relief, which according to their statements was simply not enough to live on or to support their families, those accused of vagrancy were without any kind of financial assistance. The usual procedure of arrest was that the delinquent was searched. Not possessing paper currency or a larger amount of small coins was seen as proof of begging. More money was determined as proof of either unnecessarily begging or of having begged successfully, even professionally. Less than 2 per cent of all those arrested in this sample had a valid travellers’ relief book for the Herbergen. These wayfarers usually begged “unnecessarily” for additional food or to buy cigarettes or alcohol.

The situations in which they were arrested varied. For instance, the police report might note that there had been a random identity check, or that they were found at a farmhouse or caught while begging. Some were arrested because they were drunk and disorderly. After 1934, forbidden political statements were also occasionally mentioned as grounds for arrest.

As pointed out before, this information is drawn from a random sample. Yet all the court records ever written would also not encompass the total number of people on the tramp. Rather, the sample would merely represent those picked up by the police and charged by the courts. That was, in all likelihood, highly selective, even in times of intensified punishment. Not everyone who wandered or travelled without employment or money became subject to discrimination. Evidently, the police sometimes issued merely a warning or evicted wayfarers from the place or town. People unable to work because of age or disability could be sent to an asylum instead of being sentenced by a court. Certainly a wayfarer could avoid troubles by staying within the system of Herbergen to the greatest extent possible. However, this was not the only possible context of tramping. In order to correct the image resulting from considering public administration, police, and courts alone, we have to consider carefully other representations of unemployed wayfarers.

Autobiographical Accounts

Tramping did not appear to everyone to be merely a matter of hardship. In numerous autobiographical writings of mostly skilled labourers, we find quite a variety of comments on the author's unemployed tramping. A bookbinder, who went on the tramp in spring 1926 writes: “I received unemployment benefits until April or May, and then right after the Easter holidays I went on the tramp. I had always intended to see the world; this has always been my desire”.Footnote 129 Another author emphasized the hardships of unemployment while still noting: “Wandering is a pleasure if you have eaten and the weather is fine.”Footnote 130 One might easily conclude that such autobiographical statements were strategies for idealization or justification after the fact. However, despite all the political debates on the plague of beggars and vagrants, there was at the same time propaganda in favour of tramping. A butcher journeyman who went on the tramp in 1929 writes: “Well, one fine day I got the travel bug. I wanted to see some of the beautiful wide world. I met a fellow with the same desire. And young as we were (twenty years old) and full of illusions, we went on the tramp.”Footnote 131 The hardships of tramping might become more obvious in the course of travelling or only long afterwards. “Only when I think back to that time does it really become clear to me how miserable the time was, how much we had to struggle to survive.”Footnote 132

These wayfarers could not only refer to notions of wandering and traditions of representation.Footnote 133 The phenomenon also had both a material and a social basis. Besides the public Herbergen, other sources of assistance and support were there that virtually encouraged, permitted, and defined wandering as something (still) reasonable and as a rite of passage for young men, especially in the case of craftsmen and skilled labourers. In the interwar period, trade unions and journeymen's associations still supported unemployed members with funds for travel.Footnote 134 Furthermore, travelling journeymen could call on their profession's shop owners for work and a travel allowance (Geschenk). Although the police often questioned the distinction between this practice and begging, the former was still acceptable. Some professional associations also ran their own hostels, such as those for printing and newspaper workers in Vienna.

In a publication on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the opening of their hostels, they praised the tradition of travelling as journeymen, its importance for professional training, and the value of this personal experience. Wandering was regarded as a great chance for the young printer to see the world “sweeten[ing] the days of youth, free from the monotony and the bonds of everyday life”.Footnote 135 The printers’ union regretted the obstacles to wandering created by World War I and its aftermath:

Wandering was thus impossible after the end of the war. The problems of sustenance, the difficulties of crossing national borders, the organisations’ powerlessness to provide regular travel support – all these led only the most daring colleagues to set off to travel. Most stayed at home starving. Our activities in those days consisted mostly of giving shelter to homeless and unemployed colleagues.Footnote 136

The re-establishment of regular travel support in 1926 finally revived the hostel for printers. Actual stays, however, reached only about one-third to one-quarter of pre-war levels (see Figure 3, p. 53). The union regretted this unfortunate but understandable decrease. Wandering, it pointed out, was still an up-to-date phenomenon. It was also mentioned (if only in passing) that the wandering of young printers made jobs available for the older and married ones. Since the younger ones travelled, this allowed the others to stay and support their families. Last but not least, some mobility in the labour market improved an employee's position vis-à-vis an employer.Footnote 137

The left-wing trade unions, however, knew and regretted that welfare for the wanderers was not at all their strong point but more a domain of the Catholic journeymen's associationsFootnote 138 such as the Kolpingwerk, founded in the mid-nineteenth century to help travelling journeymen. During the interwar period this organization was still running its own Herbergen in many towns. They provided shelter and meals to members, while assisting wayfarers from Austria, Germany and other countries. The Kolpingwerk data on assistance for wanderers revealed a significant increase after the beginning of the world economic crisis (see Table 2).

Table 2 Members arriving at the Herbergen of the Kolpingverein.

Source: “Aus den Vereinen”, Nachrichten des Zentralsekretariates der katholischen Gesellenvereine Österreichs, 1/2 (1933), p. 22.

However, these numbers on stays are low in comparison to those for the municipal hostels. In 1925, for instance, 2,767 wayfarers found admission at the Herberge Wels, whereas only 132 members lodged at the local Kolping house.Footnote 139

The Kolpingverein was directed towards young craftsmen and skilled workers. The journal of the association encouraged them to wander, even in the 1930s, while also praising wandering for the sake of wandering: “There are many opportunities to wander through one's native country inexpensively, especially for unemployed youth from the big cities.”Footnote 140 Wandering, it was hoped, would permit aesthetic experiencing of nature as well as physical strengthening. Further, it appeared to be a natural impulse inasmuch as conventional ideas suggested that an urge to wander was rooted within the German people. The Kolpingwerk was therefore able to highlight the relationship of wandering to Beruf (or vocation), religion, camaraderie, community, German nationhood, and the state:

You will get to know many people, both good and heartless, but they are all countrymen. We have to love and stand by them all. If we don't find jobs, we want to get to know the different tribes and dialects, the many groupings and parties, the estates and occupations and the national community [Volksgemeinschaft]. Within the family of Kolping, wandering has always had a particular seriousness and served a vocational purpose. Wandering is a school for career and life; it means proving, consolidating and broadening oneself. It requires of all of us greater self-discipline, endurance, cleverness, thrift and most of all camaraderie. Nowadays the wearisome economic difficulties seek to discourage us. We come up against closed borders. In our country, there is political unrest and mistrust. Should we therefore give up the happiness we find in wandering? […] In wandering itself there is joy and fulfilment.Footnote 141

Wandering, from this standpoint, did not mean life without any boundaries but rather integration, the finding and acceptance of one's place within the social order. This order was fundamentally defined by vocation even when there was no employment to be found.

In several respects, a particular vocation could preclude someone from becoming a vagrant. Referring to (or evoking) a tradition of wandering made tramping somehow more legitimate – despite the marginal chances of actually finding employment or gaining job experience. In contrast, an unskilled labourer named Anton Krautschneider describes his way home from a workfare programme as a humiliating experience: “I was always alert for policemen, when I sneaked through the villages, I was no journeyman with a wayfarers’ book with permission to be on the tramp.”Footnote 142 Because the institutions which hosted wanderers varied, it is not possible to estimate the total number of people on the road in the 1920s and 1930s or the particular percentage of skilled or unskilled workers accommodated. The scattered (and sometimes contradictory) evidence, however, indicates an astonishing degree of mobility.

A Question of Typology?

These appraisals of being on the road reveal a perspective quite different to those of crime records and public debates on vagrancy. Do we have to assume that these contradictory perceptions refer only to separate populations, that in fact there were merely different “types” of wayfarers on the road?

Autobiographical writings indicate how these ways of being on the road were not completely unconnected. There were ups and downs along the journey. Wayfarers could sometimes find occasional or informal employment within or outside their chosen profession. Sometimes they helped farmers in exchange for food and lodging. Although aware of the difficulties in obtaining employment, the labourers sometimes preferred to hit the road rather than work under certain conditions.Footnote 143 Did doing so then render them as unwilling to work?

From the autobiographical accounts, we can also conclude that the unemployed on the road did not rely on any single source of support. There was not a journeymen's association or Kolpingverein in every town. And even when someone was a member of one of these associations, he still often had to seek shelter and food by alternative methods. Despite being commonly criticized as a nuisance to the population, wayfarers encountered a remarkable amount of private charity, receiving support not only from their family and friends but also from monasteries, churches, unions, shopkeepers, political parties, farmers, and other residents. They might work for a pittance, sometimes collecting or stealing fruit or vegetables from the fields. Begging was very often described as an indignity in these accounts, but others were able to grow accustomed to it quite quickly. Did that make them habitual beggars?

For example, Josef Winkler, a tailor journeyman, wrote in his memoirs that he went on the tramp in 1929 owing to wanderlust. Along his journey, he used the Herbergen of the Kolpingverein, occasionally paying for lodging in a cheap inn and avoiding the public Herbergen entirely. Instead, he also begged out of a fear that his home town would be notified he was relying on public relief.Footnote 144 He also asked for food and lodging at farmhouses even when he still had money in his pockets, so as to save for worse times to come.Footnote 145 Most of the accounts describe experiences on the road as varying between the euphoria of being on the move, totally free, and the desperation later on when there was still no work to be found. There was solidarity between people on the road,Footnote 146 yet there was also a need to distinguish oneself from others: the long-term vagrants and those deemed unwilling to work. Hans Wielander, a journeymen carpenter, described himself in contrast to “professional beggars”:

[…] they had been on the road for decades – they didn't want work. They knew every farmer […], they knew where one got a hard piece of bread, and they knew every gentle soul [milde Hand]. They invited me for a beer and a snack. I didn't belong to this group of beggars; I was a journeymen. I knocked on farmers’ doors only when I was hungry or in the evenings, when I was looking for lodging. […] One should not forget that there were so many Fechtbrüder [a colloquialism for “begging journeymen”] and all were hungry.Footnote 147

This source material clearly indicates that the experience of unemployment was not uniform. We do not only find the various degrees of frustration and depression shown in a contemporary study (from the 1930s) on the unemployed in Marienthal.Footnote 148 Unemployment in other contexts could also be time free from work, a more or less illegitimate form of leisure.Footnote 149 Tramping, begging or a single conviction for vagrancy did not necessarily lead straight to exclusion or to a lasting verdict of being a “vagrant”, “work-averse” or “anti-social”. Some authors describe their encounters with the police or courts, where they faced fear and experienced shame.Footnote 150 Yet most of them could avoid problems with the police (or at least they do not mention it), and they escaped lasting exclusion.

Nonetheless, this ambiguity between necessity and (more or less legitimate) wanderlust is also to be found in the statements of those arrested for begging and vagrancy who were not so lucky. Take Mathias M., who was arrested in the Upper Austrian town of Mondsee in 1934.Footnote 151 Born in 1887 and a citizen of Tyrol, he was Catholic, unmarried, and an unskilled labourer with some previous convictions. The police report states that he was stopped by the police and told to leave town. Since he continued begging, he was eventually arrested. “There was no special necessity of begging for M. because he owns a Wanderbuch, according to which he is entitled to free boarding and shelter at the Herbergsstationen within the province of Salzburg until 15 May 1934”. The accused M. replies:

It's true, I am allowed to use the Herbergen, but I wanted to see the Salzkammergut [an area near Salzburg] because I have never been there and thus went to Upper Austria. Because I am not entitled to use the Upper Austrian Herbergen, I have been begging at several houses in Mondsee. I wanted to wander back to Salzburg in a few days.

He was arrested for forty-eight hours on account of this short trip beyond the permitted scope of wandering.

Distinguishing and identifying between the different types of wayfarers was a major concern for the police, judges and welfare institutions. This agenda met with increased difficulties during the world economic crisis, as so many were evidently forced out on to the road. Moreover, the distinction between those who were willing to work and those not willing to, became fluid and often impossible to pinpoint. Wayfarers also made distinctions by means of their method of tramping, the company they kept, their membership of an association or their use of certain institutions. In this way, the state concept of vagrancy was also an important point of reference for those on the tramp.

Conclusion

Vagrancy was not a problem of outsiders, marginality or deviance. Rather, as I have described, it relates to central questions of society and the emergence at the time of a new social policy. The punishment of vagrancy in the twentieth century was therefore not an anachronism. It was instead a consequence of a newly emerging welfare state, closely related to an attempt to formalize unemployment. Establishing support for wayfarers in search of employment was a first attempt at formalization. Unemployment insurance, together with developments in economics and transportation, contributed to more sedentariness. However, this redefined but did not fully replace other ways to find employment and support, not least because of the limited effectiveness of social welfare in that period.

When Robert Castel describes vagrancy as a particularly clear example of social disaffiliation,Footnote 152 he is indicating that mobility itself is a form and/or effect of disintegration. The tramping system described in this paper, however, shows that wandering might have endangered one's social affiliation but did not necessarily reveal or lead to it. Mobility was not at all a simple response to being out of work or impoverished. As outlined above, wandering could still serve individual and collective purposes beyond searching for a job. Tramping also demonstrates the persistence (and/or reinvention) of collective, non-governmental assistance in periods of unemployment – and notions and perceptions associated with that circumstance. Such non-governmental support also indicates that we do not have to limit questions of welfare or control to the state, although we have seen that the state was certainly an important point of reference.

James C. Scott has suggested that we consider the modern state as the enemy of “people who move around”.Footnote 153 Yet this does not mean that authorities succeeded in regulating mobility. In many cases, the state tolerated or even welcomed and enabled mobility. At issue instead was how to support “necessary” mobility and punish its undesirable forms and consequences. Moreover, we have to take into account the differing and sometimes contradictory interests of the central state and local authorities as well as different governmental jurisdictions. Vagrancy and unemployed tramping were a matter of labour market policy, criminal justice, and/or social welfare. Neither vagrancy nor the vagrants themselves were ultimately subject to one of these particular official domains. Instead, they were subject to repeated examination, definition, and reallocation, while at the same time receiving support, punishment, and education. Each of these domains has its own logic, and together they generate contradictions and paradoxes.

How people on the tramp were treated was highly arbitrary, particularly during the world economic crisis and under the Austrofascist system. Nonetheless, there were also attempts to consider individual cases based on the increasing amount of information available.Footnote 154 Techniques to register, identify, and gather information about individuals emerged, particularly in the framework of new governmental social policies. In principle, there could be a vast amount of information available on any one person. And there were many options for regulating people's movements. Nevertheless, autobiographical writings indicate that a person could still manage to be on the road for months without having trouble with the police. Records on vagrants reveal remarkable cases of people on the road for years without a passport or other identification. Laws were not always enforced in practice. However pessimistically we might judge the effectiveness of control, the creation of legality also necessarily creates illegality.Footnote 155 Nonetheless, as my paper has shown, it would be far too limiting to consider only the intentions of state policies in attempting to understand the possibilities and limitations of mobility and finding a livelihood.