Appraisal has been defined as ‘the process of periodically reviewing one's performance against the various elements of one's job’ (British Association of Medical Managers, 1999). This definition underlines the fact that appraisal refers to a person's performance within a defined role and that the appraisal should take account of the variety of tasks, roles and responsibilities of individuals. There is an explicit distinction between appraisal and assessment, in that the latter usually involves judgements against defined criteria.

Appraisal systems were originally introduced in industry in recognition of the need to evaluate the performance of individual members of staff, although the actual aims of the systems and processes used have varied considerably. A survey conducted in 1986, for what is now the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), found that the vast majority of employers operated performance appraisal schemes and that these were used to review the past performance of employees and to set future objectives. In addition, the employers reported that the appraisals were intended to help improve performance through the identification of training and development needs and to assist with the assessment of future potential and decisions on career progression (Reference HoggHogg, 1988). Many appraisal systems were linked to performance-related-pay arrangements. Further investigation by the CIPD in 1991 and 1998 revealed that appraisal was a top-down process involving the setting of objectives and the review of results against such goals, with heavy reliance on weighting scales (Reference Armstrong and BaronArmstrong & Baron, 1998). It can therefore be seen that appraisal can be used in a variety of ways.

The context of appraisal

Appraisal of consultants has been introduced into the National Health Service (NHS) in the context of increasing public concern about the quality and safety of clinical performance. In Britain, the public concern is particularly well exemplified by the inquiry into the management of the care of children receiving complex cardiac surgical services at the Bristol Royal Infirmary between 1984 and 1995. The inquiry focused attention on the managerial systems that failed to prevent the tragic events in Bristol (http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/index.htm).

Two further high-profile inquiries questioned not only clinical performance but also personal behaviour. These were the Royal Liverpool Children's Inquiry (the need for which arose from evidence given to the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry), concerning the practice of removing and retaining organs following post-mortem examination (Reference Redfern, Keeling and PowellRedfern et al, 2001) and the clinical audit commissioned into Harold Shipman's clinical practice (Department of Health, 2001a ). Statements within the Royal Liverpool Children's Inquiry report included ‘a further aggravating feature has been Professor Van Veltzen's behaviour, including exaggeration, falsification of accounts including both financial and human resources, fabrication of post-mortem reports’ (Reference Redfern, Keeling and PowellRedfern et al, 2001). Of course, in Shipman's case, the incidents were a direct result of his criminal behaviour.

There are other commonalties in the findings of these reports. For example, in the Shipman report a key section of the recommendations concerned monitoring performance and opened with the statement, ‘Shipman did not undergo, at any time during his career, a review of his clinical performance that was sufficiently searching… This points to a lack of accountability that is not acceptable’ (Department of Health, 2001a ). In the Bristol Royal Infirmary report, many recommendations fall within the section headed ‘Competent healthcare professionals’, which opens with the words ‘broadening the notion of professional competence’ and proceeds to make clear recommendations both about that concept and about how it might be regulated (http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/index.htm). The implication here is that a managerial system such as appraisal might have served to identify these events sooner or, indeed, might have prevented them.

Public concern about the adverse outcomes of clinical practice is, of course, not merely a British phenomenon. For example, in the United States, the Institute of Medicine's recent report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Institute of Medicine, 1999) was widely seen as confirming what most already feared: that medical interventions were accompanied by unacceptably high levels of preventable harm (Reference Barach and SmallBarach & Small, 2000). However, the emphasis in this report is on how the healthcare system functions as a whole and how to re-engineer its processes to achieve a significant reduction in the degree of risk of harm to patients.

The response to these public concerns has been a series of policy documents, structural reforms and new agencies with specific responsibilities, all of which aim to ensure higher quality of care and explicit accountability arrangements. These include the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (http://www.nice.org.uk); National Service Frameworks (http://www.doh.gov.uk/nsf/nsfhome.htm); clinical governance (http://www.doh.gov.uk/clinicalgovernance/index.htm); the Commission for Health Improvement (http://www.chi.nhs.uk); the NHS Plan (http://www.doh.gov.uk/nhsplan/default.htm); the National Patient Safety Agency (http://www.npsa.org.uk); and the National Clinical Assessment Authority (NCAA) (http://www.ncaa.nhs.uk). Most of these are now well known but the NCAA has received less publicity, so it is worth explaining that it was formed in April 2001 to provide a service to support and help implementation of systems for assessing the performance of doctors in the NHS and deal with those whose performance gives cause for concern. A further important development, following the government's response to the Bristol Royal Infirmary inquiry recommendations, is the establishment of a new Council for the Regulation of Healthcare Professionals (Department of Health, 2002c ). The relationship between the General Medical Council and this new Council is not yet clear. What is beyond doubt is that we are in new territory with regard to the autonomy of the professions.

Appraisal of senior doctors can be better understood in this context. Prior to these events, senior doctors, particularly consultants but also general practitioners and others, had been regarded as independent or semi-independent practitioners, outside any supervisory system or arrangement. There has been a perceived need to design and adopt open systems and processes that command the confidence of professionals, managers, public and politicians alike and that restore public and political trust. There will also be a change in the arrangements for the registration of doctors by the General Medical Council. There are ongoing discussions about the regular revalidation of all doctors from 2004. For the first time, doctors will have to provide evidence to demonstrate their continuing fitness to remain on the medical register. This is a major change from the current arrangements, whereby a doctor remains on the register indefinitely, as of right, unless there is a reason for his or her removal. In other words, the default position will alter. For most doctors, appraisal will form the basis of the revalidation process.

The expressed concern within the context of the modernisation of health services to improve the working lives of doctors within the NHS (Department of Health, 2002b ) is in a separate and more developmental line. Consideration is being given to proposals for the career development of senior doctors. These recognise the changing nature of the skills and expertise of consultants over time, such as described by Kennedy & Griffiths (http://www.scmh.org.uk/8025694D00337EF1/vWeb/fsPCHN587EYZ) in their study into concerns of consultant general psychiatrists. They found that the traditional role of the general psychiatrist was proving difficult to sustain and a number of roles were emerging for the psychiatrist in adult mental health which incorporated changing case-loads, clinical styles and managerial roles. Appraisal is viewed as one of the main enabling tools by which this type of change will occur.

The purpose of appraisal is broadly the same across all areas of work, including medicine, although its implementation may need to be refined to reflect the context and the nature of the particular functions. The scheme introduced by the Department of Health assumes that the systems and content of appraisal will be largely generic across the medical specialities. Its application in a mental health context is considered below.

The appraisal process

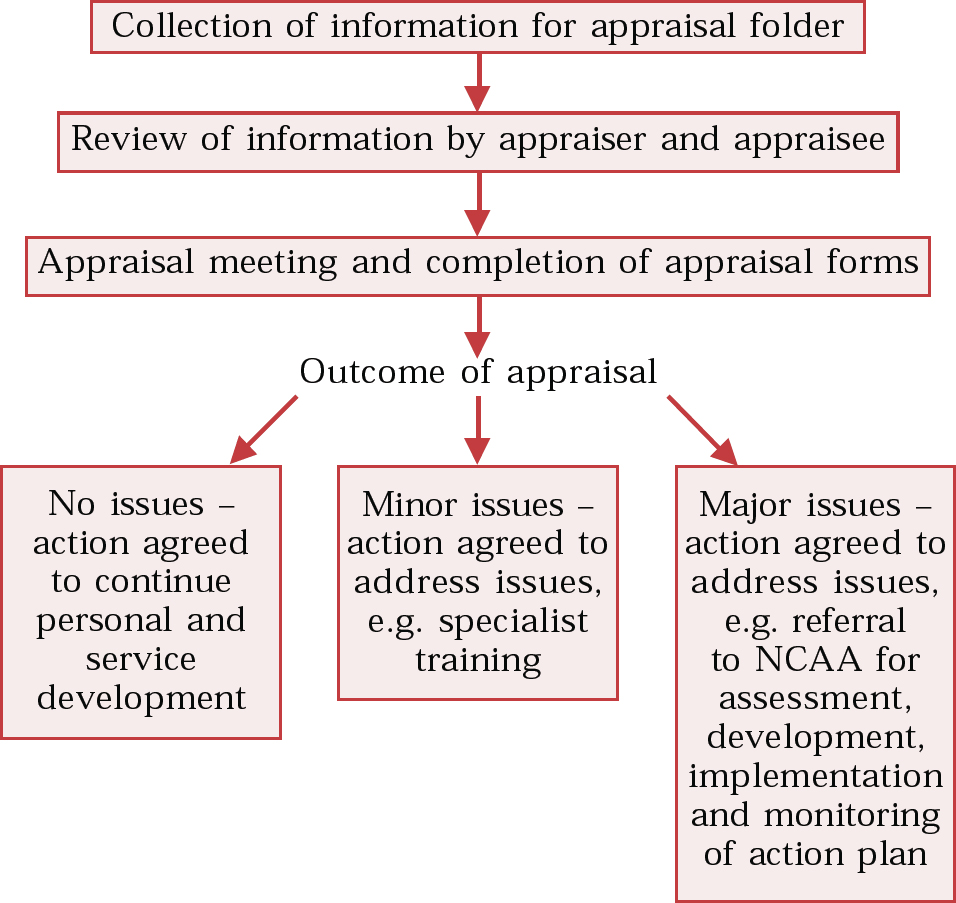

The Department of Health published two advance letters (MD 6/00 and MD 5/01) which introduced compulsory appraisal for consultants and set out the format for the collection and presentation of necessary information (Department of Health, 2000; 2001b ). They set out the aims of the appraisal scheme and the processes and documentation to be used. The appraisal scheme (Fig. 1) has been introduced as a positive process to give feedback to consultants on their performance and to identify development needs. Its primary purpose is not to see if doctors are performing badly but to help improve good performance. However, it can help recognise the development of poor performance or ill health.

Fig. 1 Appraisal process.

The advance letters make it clear that the chief executive is ultimately responsible for ensuring that consultant appraisals take place. The medical director will conduct the appraisal of clinical directors, and clinical directors will be responsible for conducting appraisals of consultants who work within their directorates. The chief executive will nominate an individual who will conduct the medical director's appraisal. This must not be somebody whom the medical director has appraised. Only consultants on the medical register can appraise other consultants.

Before the appraisal, a certain amount of information has to be collated and this is discussed in more detail below. The advance letter also advises that the appraiser might wish to consult with others, including members of the care team. The paperwork should be reviewed by both the appraiser and the appraisee at least 2 weeks before the appraisal meeting. It seems likely that both appraiser and appraisee will require about 1 hour to prepare for the appraisal meeting.

The appraisal is usually conducted in a one-to-one interview. It is recommended that all appraisers are specifically trained for this task. It is important that the appraisee becomes clear about exactly what to expect from the appraisal, so that any negative feelings and insecurities can (at least in part) be reduced (Reference Jackson, Gale and BishopJackson et al, 2001; Reference WilkinsonWilkinson, 2001).

Appraisers will need the consideration and support of their colleagues and organisations and must understand their responsibilities and accountabilities in relation to appraisals. Their significance is underlined by the fact that the appraiser has to declare his or her own General Medical Council number on the appraisal documentation.

The paperwork sets out the agenda and specific points to be addressed during the appraisal, and this should be reviewed by both appraiser and appraisee before the meeting. The current position needs to be agreed, strengths reinforced and problems identified. The paperwork could make the appraisal meeting rigid and inflexible, but it is important to keep in mind that appraisal includes pastoral aspects, and both parties should feel free to raise issues not directly covered by the documentation. For the process to be meaningful, the appraiser has to have the authority, in the light of the appraisal, to recommend changes that are likely to be implemented.

Individuals who hold joint appointments with two or more NHS trusts will need to establish the arrangements that will apply to them. The Department of Health recommends that the appraisal is conducted within one trust, with communication with the other(s). In some cases, a joint appraisal might be preferred. For individuals who hold academic appointments with honorary contracts with NHS trusts, the requirement is that they be appraised in the same manner as their NHS colleagues. The Department of Health has advised that there should be one joint appraisal process for such individuals with the university and the NHS trust agreeing on two appraisers, one of whom must be on the medical register (http://www.doh.gov.uk/nhsexec/consultantappraisal/index.htm).

The advance letters are of relevance only to doctors employed by the NHS. Doctors who work for institutions such as the Mental Health Review Tribunal or the Department of Social Security will need to establish what their appraisal arrangements will be and will need to collect a similar data-set. Consultants who are employed in private psychiatric practice and are not affiliated to an institution will also have to make appropriate arrangements.

Information for appraisals

The advance letters establish a framework for the appraisal information, based on the elements in Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 1997; Box 1). Each consultant is required to prepare an appraisal folder while the appraiser prepares a workload summary. There is therefore some ambiguity about whose responsibility it is to provide all the necessary data on which a successful appraisal is dependent, but there is an implicit assumption that this is the responsibility of the employer, i.e. of the NHS. However, it is important for doctors to be aware that this appraisal process will form the basis of revalidation with the GMC and that the GMC's relationship is with individual practitioners. Thus, the expectation is that the individual practitioner will be responsible for ensuring that the data-set is complete, but that it has to be agreed by the appraiser.

Box 1 Framework for appraisal information and documentation requirements (after Department of Health, 2001b)

Good medical care

Current job plan

Indicative information regarding annual caseload/workload

Audit data and methodology

How results of audit have changed practice

Clinical outcomes compared with professional recommendations

Resource shortfalls compromising outcomes

How in-service educational activity has affected service delivery

Outcomes of formal complaints

Outcomes of external reviews

Issues arising from adherence to clinical governance policies

Critical incident reports

Any other routine indicators of standards

Maintaining good medical practice

Any difficulties in attending continuing professional development (CPD)/continuing medical education (CME) activities

CPD activity (list all CPD courses and points awarded)

Working relationships with colleagues

Description of work-setting and team structure

Peer reviews or discussions

Relations with patients

Examples of good practice or concern

Description of approach to handling informed consent

Validated patient surveys

Changes in practice following complaints, compliments, peer reviews/surveys

Teaching and training

Any difficulties in arranging cover while teaching and training

Summary of formal teaching/lecturing activities

Summary of supervision/mentoring duties

Recorded feedback from those taught

Probity

Any concerns or problems

Health

Any concerns or problems

Management activity

Formal management commitments

Noteworthy achievements

Recorded feedback

Any difficulties in arranging cover while undertaking management activity

Research activity

Formal research commitments

Research – ongoing or completed

Funding arrangements for research

Noteworthy achievements

Confirmation of ethical approval for all research

Development action in past year

Development action agreed at last appraisal meeting or personal development plan

Goals achieved/further action required

There are some limitations to the format. Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 1997) focuses on clinical performance. However, there are no established national norms for workload for the different sub-specialties in psychiatry, nor is there an agreed parameter for measuring workload. On the one hand, it is easy to assume that measures such as numbers of new patients seen within a defined period, numbers of follow-up appointments, numbers of in-patients, etc. are ideal measures. On the other, it is recognised that the severity or complexity of the conditions presented by the patients also influence the burden of work. Furthermore, there are no agreed audit measures that accurately reflect the quality of clinical practice. There are exisitng methods for measuring all this, but they are resource-intensive. Although there are peer-review instruments such as that validated by Reference Ramsey, Wenrich and CarlineRamsey et al(1993), which could be used to assess ‘working relationships with colleagues’ they are yet to be implemented widely. It might be argued that the area of ‘relations with patients’ can be particularly difficult to assess in psychiatry. It might be preferable for global patient satisfaction surveys, perhaps based on Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 1997), to be used as a proxy for this and for exceptional complaints to be used as a direct measure of a particular doctor's relationships with his or her patients. Of course, this would still not capture relationships that work well. Recorded feedback from those being taught is required as part of the documentation on ‘teaching and training’. Attendees will be asked for feedback after some teaching sessions but this will not always be easy to capture, especially where teaching is informal and ongoing, such as with junior doctors and medical students.

Although the advance letters specifically refer to consultants, if the documentation is to form the basis of revalidation with the GMC, it will need also to apply to other doctors, including doctors-in-training and those in non-consultant career-grade posts. It should be noted that the documentation is comprehensive and not all aspects will be relevant or applicable to all doctors.

Discussion

In principle, appraisals should be welcomed by consultants. They provide an opportunity for a comprehensive review of an individual's performance and support further development. Furthermore, research at Aston Business School has been reported as showing that appraisal has a strong association with lower patient mortality rates in acute hospitals (Anonymous, 2002a ).

However, the introduction of an appraisal system is not without difficulties. One of the characteristic expectations of appraisal is that its conclusions will be used in a developmental way. The Department of Health's (1999) consultation paper Supporting Doctors, Protecting Patients emphasised this point by stating that ‘it is not the primary aim of appraisal to scrutinise doctors to see if they are performing poorly but rather to help them consolidate and improve on good performance aiming towards excellence’. Whatever the reassurance, however, given the context of its introduction, the public and political expectation is of a process that will clearly identify poor performance, with a natural implication that those identified as being in need of remedial action will receive the necessary training and, in the event of failure to respond to such training, will be dismissed and prohibited from further practice.

There is a risk that this expectation will affect the implementation of the appraisal system. It has been argued that the model of regulation being used in the NHS is moving from one based on a compliance approach, which assumes that organisations are basically good and need support, towards one based on a deterrence approach, which assumes that organisations are basically bad and have to be forced to behave well (Reference WalshWalsh, 2002). It is therefore possible that pressure could be brought to bear so that an appraisal system designed to be used in a positive way to support performance and development could be used in a negative way to identify failure and take remedial action.

There is also a risk that the behaviour of those being appraised could start to be distorted. Some managers are finding that their jobs are dependent on the achievement of certain centrally determined targets and it has been suggested that this might force them to indulge in perverse behaviour such as ignoring local conditions when determining organisational priorities (Anonymous, 2002b ). Although there are currently no agreed norms for performance, it is conceivable that these will develop over time and, if they become integral to appraisal, it is possible that clinicians’ behaviour will be similarly influenced by them.

There is also a structural difficulty in the creation of the personal development plan for psychiatrists. This should flow naturally out of the individual appraisal meeting but is at present conducted under a different, peer-group system under the auspices of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. A formal system for the establishment of peer-group personal development plans introduced in Leeds has recently been described in APT by Reference NewbyNewby (2003), who argues that development objectives identified through appraisal can be turned into personal development plans within the peer group. It might be that this approach can bring these two separate processes together.

Our own experience is that investment of time is considerable. There is a real question about the best way to make this an efficient and effective process. The emphasis in the current arrangements is on the appraisal of the individual, whereas in psychiatry, in particular, much of our work is organised in teams and, arguably, a whole-system approach should be taken to appraisal. The NHS is beginning to recognise this, as evidenced in a letter from the Director of Human Resources at the Department of Health (2002a) that emphasises the extent to which good teamwork contributes to effectiveness and innovation in health care delivery. The individual must be seen within that concept and reality.

The challenge is how to transform a potentially rigid system into a dialogue that focuses on personal, professional and educational needs. The approach of a checklist-style appraisal will make for greater difficulty in capturing the totality of clinical and personal performance. Perhaps what will emerge, in due course, is a system that uses varying degrees of depth. Thus, all individuals could be screened using a basic data-set and a deeper, more-probing process could be put in place where necessary. This approach would balance some of the time and information constraints while enabling all individuals to use the process of appraisal positively for their own personal and career development.

Multiple choice questions

-

1 Appraisal is:

-

a the process of periodically reviewing the different elements of an individual's job

-

b the process of assessing performance against defined criteria

-

c conducted in one-to-one interviews

-

d usually supported by paperwork

-

e intended to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the appraisee.

-

-

2 Appraisal for consultants has arisen in the context of:

-

a increasing confidence in the competence of doctors

-

b evidence that doctors are motivated by appraisals

-

c high profile inquiries into medical errors and scandals

-

d public concern about adverse outcomes of clinical practice

-

e plans to introduce revalidation of all doctors by the GMC.

-

-

3 Information for appraisal should include information on:

-

a current job plan

-

b CPD activity

-

c health problems

-

d annual leave

-

e titles of lectures given.

-

-

4 The possible outcomes of appraisal include:

-

a summary dismissal from post

-

b referral to the National Clinical Assessment Authority

-

c annual agreement of a personal development plan

-

d referral to the GMC's performance procedure

-

e negotiated change of job plan.

-

-

5 Limitations of the process of appraisal include:

-

a restriction of professional clinical autonomy

-

b undermining the integrity of the clinical team by the appraisal of individuals

-

c few clinical directors being competent to appraise their clinical colleagues, because of sub-specialisation

-

d non-existence of comparable data on workload

-

e doctors being appraised by non-clinical managers.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.