Taste is the sole sense to have a dedicated capital vice: its denigration is simultaneously epistemological, aesthetic and ethical.Footnote 1

Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier.Footnote 2

Ever since its philosophical treatment by Xenophanes of Colophon in the fifth century BCE, the sense of taste has enjoyed a dubious position in the hierarchies of human knowledge and experience, being systematically denigrated to the benefit of ‘the noble sense’ of vision that secures the mind's true access to the world and its beauty.Footnote 3 Associated with an organ, the tongue, that mediates bodily needs and pleasures as well as reasoned speech, taste presents itself alternatively as a ‘pleasure that knows’ and a ‘knowledge that does not know, but enjoys’.Footnote 4 In highlighting this troubling ambivalence, philosopher Giorgio Agamben has captured the way in which taste thereby troubles the categories of thought as either ‘an empty or excessive sense, situated at the very limit of knowledge and pleasure’.Footnote 5

This categorial ambivalence has afforded taste a unique and uneasy status in natural, moral and aesthetic philosophy. While all senses are defined by some measure of physicality, the physicality of taste has made it more suspicious and problematic than others. As it anchors those physiological functions that carry the greatest value in the realm of necessity (i.e. survival) and the greatest stigma (e.g. religious taboo) in the realm of culture, taste is inevitably entangled with political and civilizational anxieties over the disciplining of the human body. Throughout recorded history, social and moral discipline has operated on the body as property, on physical labour as its productive output, and on its needs and pleasures, through the ‘civilising of hunger’ as a physiological drive and the ‘civilising of appetite’ as a ‘state of mind’.Footnote 6

Because needs and pleasures are themselves shaped and constrained by the social distribution of power and wealth, enunciations of what does and does not constitute ‘good’ or ‘pure’ taste necessarily mediate social judgements and distinctions that order people by classifying and contrasting their bodies, labour, experiences and aesthetic dispositions.Footnote 7 Food constitutes the ideal domain for the deployment of such judgements, as it embodies both needs and pleasures, and carries, through its ingredients, modes of preparation and manners of consumption, all the markers of the cultural and socio-economic order.Footnote 8 In this order, the ‘tastes of nature’ of the deprived and the ‘tastes of freedom’ of the privileged are experienced and viewed as natural preferences, and therefore judged as moral markers of character and worth.Footnote 9 As they reflect the binaries of the social structure of which they are mere products, expressions of one's personal taste thus necessarily imply their negative corollaries, often explicitly rendered as a natural dis-taste or a physiological dis-gust for the tastes and experiential dispositions of others.Footnote 10

By showing how these dynamics operate in everyday social practice but also in the domain of aesthetic philosophy itself, Pierre Bourdieu's Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste illuminated the structural entanglement of social and conceptual hierarchies that renders philosophical statements on taste ideological reifications and discursive performances of the established social order. As long as this entanglement remains hidden, our understanding of social reality is distorted by a ‘scholastic bias’ that perpetuates the unconscious erasure or ‘misrecognition’ of the social foundations of intellectual judgement.Footnote 11 The task of a critical, reflexive social epistemology, then, is to ‘recognize’ the entanglement of the two hierarchies – social and conceptual – in the discourse of philosophy and science, and identify the ways in which this entanglement is constituted, made invisible and endowed with performative efficacy.

In this article, I propose to deploy the social epistemology of taste within a wider, comparative framework of sociohistorical analysis. Any discourse and practice of taste are necessarily grounded in their historicity. Careful engagements with specific historical configurations of knowledge and society are therefore necessary to understand the singular histories of taste as they have unfolded in various times and places. Beyond their singularities, these histories can also reveal something more general and more constant about taste itself and our various relations to it. The article attempts to capture that social essence of (the problem of) taste by examining four major socio-epistemic configurations in the history of ‘Western’ knowledge, starting from the ‘revolutions of wisdom’ associated with the establishment of rational philosophy and science in Greek antiquity.Footnote 12

Given the wide time frame and multidisciplinary scope of this analysis, the methodology adopted here aims to extract the greatest possible analytical and argumentative value within the constraints of a limited, article-length intervention. Accordingly, I chose four distinctive and equally important moments in the social history of Western European knowledge, in which the status of taste is manifested objectively in both discourse and practice. I treat all four historical vignettes within a unified comparative framework that focuses systematically on the articulation between their respective intellectual and social contexts. To reconstruct these contexts and highlight continuities and transitions between them, I draw on a combination of primary texts, secondary historical and scientific sources, and anthropological case studies and analyses.

The article begins where ‘Western’ epistemology identifies its own beginnings and foundations. The first section examines the earliest systematic devaluation of taste operated by the Socratic philosophers as they defined philosophical knowledge in opposition to the knowledges of competing epistemic labourers, especially cooks and the Hippocratic physicians. The latter's elevation of taste as a legitimate form of knowledge represented a valorization of physical labour and skills that threatened the established aristocratic order of Athenian society. The philosophical taming of taste in an arbitrary hierarchy of the senses thus served to contain and delegitimize alternative conceptions of the citizen, by reasserting the inferiority of those who were naturally incapable of becoming integral and rightful members of the social order.

The second section follows the resurgence and transformation of Hippocratic thought and practice in the Galenic theory of humours that dominated Western science throughout Europe's ‘medieval’ and ‘Renaissance’ periods. Here, I describe the entanglement of the humoural doctrine with the racial and religious orders of empire, as Europeans encountered ‘Old World’ and ‘New World’ peoples whose existence threatened the hierarchies of identity that imperial rule needed to sustain and justify itself. Before the consolidation of a properly racialist view of humanity in the modern period, the theory of humours mediated the ordering of peoples on the basis of their natural tastes. ‘Old World’ and ‘New World’ crops, like the aubergine and maize, thus served as proxies to classify humanity and assert the inferiority of those who could not be recognized as equal.

The third section examines the mechanisms of social distinction and erasure that operated in the early modern scientific period as the senses became invested with a new epistemic authority. It focuses specifically on how British empiricist philosophy solved the problem of taste's subjectivity by anchoring it in the cultural hierarchy of the social order. This is illustrated through an engagement with the occluded meanings of ‘knowing the pineapple’ that featured prominently in philosophical and social discourse, at a time when the pineapple symbolized the power, superiority, refinement and distinctive taste of the ruling aristocratic elite.

The fourth section examines the socio-epistemic landscape of taste following the advent of the ‘Green (agricultural) Revolution’, the post-war restructuring of social classes displaying new gustatory behaviours, and the recent rise of the science of taste. This final section follows the resurgence of social distinction in the resistance to the globalization of food systems and to the democratization of culinary tastes that is deployed by various social groups now invested in the meaning of taste and its arbitration. The focus here is on the professional, cultural and philosophical domains of wine appreciation, across which a socially exclusivist standard of taste is asserted in the residual spaces left open by the new scientific standard.

In each of these four vignettes, the discourse of taste is shown to be inscribed in a particular conception of the social order that it simultaneously expresses and performs by reproducing its distinctions and erasures in the form of epistemic demarcations. The persistence of this pattern across substantially different historical contexts reveals the profoundly social nature of ‘the problem of taste’. More than any other sense, taste carries the subversive claims of those whose aspirations and modes of being disrupt established social hierarchies of power and worth. Whether the resolution of the problem of taste entails erasing, devaluating or taming taste, the paper suggests that such epistemic strategies always also operate as a form of social discipline.

Episteme–logos versus the lower senses: social erasures at the foundation of philosophy

The part of the soul that has appetites for food and drink and whatever else it feels a need for, [the gods] … tied [it] down like a beast.Footnote 13

The hierarchy of the senses that the Socratic philosophers established in the fourth century BCE has shaped philosophical investigation ever since and continues to inform contemporary philosophy's general neglect of the sense of taste.Footnote 14 This hierarchy is delineated in key Platonic and Aristotelian texts that distinguish the higher ‘distance senses’ of sight and hearing from the lower ‘contact senses’ of smell, taste and touch.Footnote 15 Because it is associated with the lowliest, most uncivilized parts of the body, its needs and its pleasures, substantial effort was dedicated to putting taste in its right place within this hierarchy. The full extent of what was invested and what was at stake in this careful act of epistemological devaluation can only be grasped sociologically, by reconstructing the context in which philosophy was constituted, both as an intellectual project and as a social profession emerging in competition with others.

The space in which Plato enunciated the nature of philosophy was indeed a crowded social space in flux. This was a space of transition from tradition to innovation and the theatre of antagonistic encounters among the contenders to what Marcel Detienne has called the ‘truth masters’ of the archaic age – the seer, the poet and the sage – in a social environment increasingly centred on the public place, where speech was secularized, liberated from social monopoly and openly agonistic.Footnote 16 Across the intellectual field, self-definition carried by a rhetoric of legitimation became the mark of a new generation of intellectual aspirants trying to carve their position out of the territory of the elders through the elaboration of new genres of prose.Footnote 17

In this context, the legitimation of the project of philosophy required an overarching meta-discourse that could determine the nature and comparative value of competing forms of knowledge. It required, in other words, a theory of knowledge – what has since been known, because accepted, as ‘epistemology’. The philosophical episteme–logos complex thus became a point of convergence of the oppositional threads that carried the distinctiveness of the philosophical project against the old authorities and the new contenders occupying the intellectual space of the Athenian polity.

The first function of epistemology was to bring out philosophical knowledge as distinctive from and superior to the many forms of wisdom (sophia) and knowledges (epistemai) that had been inherited from the archaic age, whose epic heroes were the mythologized versions of its historical heroes – the technicians, artisans, engineers and other skilled workers inhabiting the celebrated domains of art, justice, politics, war, science and architecture.Footnote 18 To ‘know’ in the Homeric age had meant to interpret a sign, to report on what one had seen, or to have a skill.Footnote 19 But in the transition to the classical age, two drastic transformations were effected by the philosophers, namely a shift from knowledge-as-skill to knowledge-as-vision and a shift from science-as-doing to science-as-knowing.Footnote 20 Wisdom was thereby reconfigured metaphysically, becoming detached from matter, technique, experience and practice. Plato relegated wisdom to the humanly inaccessible domain of divine knowledge and simultaneously redefined human knowledge as true opinion grounded in the recollection of the divine world of Ideas, to which the Soul, being of the same substance as the world, had privileged access.Footnote 21

This distinctive knowledge was asserted as the privilege not of the wise men (sophoi) of the worlds of practice and experience, but of the philo-sophos, a new expert whose specific rationality was self-consciously defined against competing, operational modalities of reason, of which the stochastic intelligence (metis) of the practitioner was the first to be irrevocably erased.Footnote 22 What made the philosopher's knowledge superior was its access to the real ‘real’: not the real as manifested materially through experience, technique, and practice, but as unmediated, captured through a logos that was now tied to an independent signifier, Being.

The invention of philosophical ‘truth’ can thus be understood as the pragmatic solution to a practical problem: a way of settling, socially, not the imagined and artificially controlled debate carefully crafted in Plato's dialogues, but the actual confrontation taking place in the Athenian cultural market of competing ideas and competences deployed as ‘symbolic goods’.Footnote 23 The second line of attack against philosophy's competitors was therefore to undermine their social status, a process that entailed the erasure of their knowledges as legitimate alternatives. In the rhetoric of delegitimation of everything non-philosophical thereby deployed, the ‘vocation’ of philosophy was simultaneously defined as an exclusive and elevated social identity.Footnote 24 The socio-epistemic devaluation of gustatory taste was operated twice in this process, as the philosophers established the primacy of theoria against both empeiria and techne, and hence against the practitioners who elevated taste aesthetically and functionally.

Described as practice derived from sense experience and memory and constituted through trial and error, empeiria was placed below techne, which applies true reasoning and first principles to production.Footnote 25 In Gorgias, the example given of an empeiria is opsopoia, which is interpreted as food making and cooking.Footnote 26 Cooking was the privileged domain of gustatory taste and thus engaged all that was intellectually and socially devalued from the philosophers’ perspective. Plato explicitly expressed his denigration of eating and drinking as lowly bodily activities driven by the stomach's animalistic appetite, and of the lowly pleasures they brought to those who lustfully abandoned themselves to these illusions.Footnote 27

If taste was a lowly medium of engagement with the world, then those who mastered its principle and practice carried a double stigma, as physical labourers and as the specialists of an inferior physical skill. As cookery and gastronomy began their socio-professional ascension alongside philosophy, the latter marked them down as vulgar and irrelevant.Footnote 28 Aristotle described cookery as a ‘servile’ branch of knowledge, appropriate only for slaves and servants.Footnote 29 While cooks strove to establish themselves as dignified professionals who took pride in study and experimentation, the philosophers succeeded in ‘discredit[ing] their way of living and the place of gastronomic connoisseurship in the aristocratic mechanisms of social recognition’.Footnote 30 As John Wilkins has shown, the social ridicule accompanying professional cooks’ self-assertive attitude was notably registered in ancient Greek comedy in the pathetic character of the ‘boastful chef’, who confused his lowly field of expertise with the field of dietetics.Footnote 31

Firmly separated from cookery in the philosophers’ conception, dietetics belonged to the techne of nutrition and hence to medicine, but its higher valuation only served to fine-tune the overall social hierarchy of epistemic labourers. Techne was delegitimized as productive labour, through an argumentative move that drew on the concept of banausos, originally a vague category that marked the non-citizen, now used to delineate a hierarchy of forms of knowledge doubling as a ‘hierarchy of the people possessing such knowledge’.Footnote 32 Banausos would end up including everyone excluded from philosophy, its powerful devaluation manifesting an explicit conception of an ideal political order from which manual labourers were systematically excluded.Footnote 33 In the process of justifying this order epistemologically, Plato and (perhaps more subtly) Aristotle articulated what Benjamin Farrington described as an ‘ingenious piece of sophistry’, namely the notion that ‘it is not the man who makes a thing, but the man who uses it, who has true scientific knowledge about it’.Footnote 34

Marxist commentators have recognized in the philosophers’ hierarchy of knowledges a social–moral hierarchy informed by, and meant to preserve, the division of labour and power within Athenian society, especially as it pertained to aristocratic rule and slavery.Footnote 35 The shift from science-technai to science-epistemai can thus be viewed as opposing the free (male) citizen and master to the working non-citizen and slave, the word to the deed, the head to the hand.Footnote 36 This hierarchy was reinforced by the philosophers’ insistence on the peculiar notion that techne could not be taught and learned, thereby precluding its mediation of any form of upward social (and moral) mobility.

This hierarchy of knowledges provided the foundation for a hierarchy of theories of knowledge, grounded in the same oppositions carried at a metalevel. What was at stake, here, was the authority to arbitrate epistemic disagreement. The antagonistic figure of the sophist mobilized by Plato in his textual strategy served to reassert the sovereignty of logos in this process, so that arbitration was played out within the realm of discourse and rhetoric alone, and knowledge itself was exclusively reduced to propositional knowledge. The sensory power of the tongue to capture truths about the world was thus erased to the benefit of its discursive power to formulate true statements about it.

The long-standing historiographical view according to which philosophy was born in reaction to scepticism and sophism thereby operates as a convenient myth of origin that hides the erasure that the move to episteme–logos enabled. This erasure was the disqualification of an alternative theory of knowledge. Grounded in a positive science of nature, this alternative was represented by the only epistemic labourers capable of competing with the philosophers on the basis of an independently validated knowledge and through the same literary medium otherwise used to disqualify those devoid of logos, whether slaves, artisans or cooks. These alternative epistemic subjects were the physicians (iatroi) of the Hippocratic corpus.

The Greek physician was at the time considered a type of demiourgos, that ‘secret hero’ of Greek history whose social status became devalued in the classical age.Footnote 37 The demiourgos was the subject of productive labour (erga) put at the service of the public, and thereby represented an old conception of the artisan as the maker of the kosmos and the polis, and of labour as intrinsic to the constitution of the community. In the archaic age and outside Athens in the classical age, the demiourgos was still regarded as a sophos, in whose wisdom technical skill and intellectual speculation were not yet divorced.Footnote 38 In the new epistemology, however, the demiourgos's knowledge as techne became disqualified as antagonistic to theoria and was placed below practical reason (phronesis), which, as opposed to techne, was considered an end in itself. The physician was thereby naturally excluded from the domain of true knowledge and a fortiori from the theory of knowledge.

The Hippocratic physicians were conversely involved in claiming medicine as a proper, socially meaningful techne and in raising the value of techne as a distinctive, legitimate form of knowledge from which an alternative theory of knowledge could be derived. They, too, were engaged in the agonistic confrontations of the age, struggling to constitute their social identity in the absence of any regulation of their profession.Footnote 39 In this struggle, they were opposed to the old truth masters (prophets, magical healers, soothsayers), to the emerging philosophers, and to suspiciously viewed insiders, denounced as charlatans, who promoted a non-technical medicine permeated by philosophical a priori and mediated by the spread of written treatises claimed as substitutes for the hands-on experience of the healers.Footnote 40

In key texts of their corpus, the Hippocratic physicians delineated a dynamic conception of the nature of their craft as constantly evolving through practice, and of how it illuminated larger questions of scientific reasoning and of natural philosophy. Against the philosophers’ a priori taxonomies, the physicians argued that generalizations must be grounded in the observation of special cases, and that speculative thought could only derive from and be guided by observations supported by sense experience and by trial and error.Footnote 41

Taste played a central role in this paradigm, as it was engaged both in knowing the disease (diagnosis – literally, ‘knowing through’) and in treating it. As explicitly stated in the central Hippocratic treatise on Epidemics, the ‘whole body’ of the physician, ‘vision, hearing, nose, touch, tongue, reasoning arrive at knowledge’ in diagnosing, for which vision is often of limited capacity.Footnote 42 Far from being disregarded, the patient's own sense perceptions and subjective states, such as their sense of taste and their appetite, were thus given significance as manifestations of the real. One's perception of one's body was hence indirectly granted an epistemic authority otherwise rejected by the philosophers.

These differences were further reflected in the incorporation of food in the patient's regimen of health and the recognized relation between cookery and medicine, represented in the fluid contours of dietetics.Footnote 43 In Hippocratic recipes–remedies, the line between medicament and food was voluntarily blurred to enable the physician to accommodate, in principle and practice, the functional versatility of edible substances, like garlic, that could not be captured by analytical taxonomies.Footnote 44

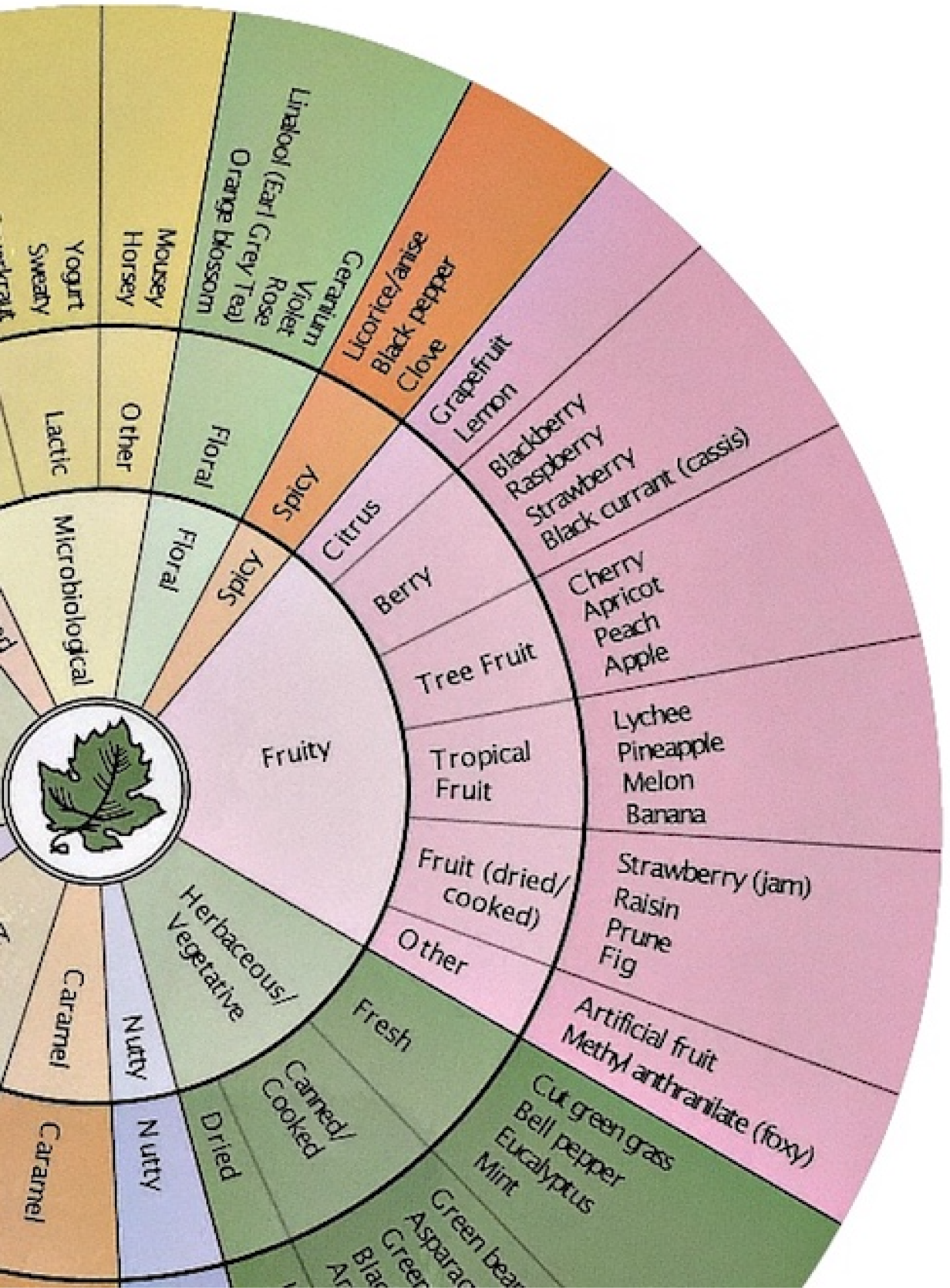

While their praxis-based theory of knowledge failed to constitute an influential alternative to epistemology, the principles and practice of the Hippocratic physicians flourished in the medieval and Renaissance periods – the ages of the artisan, technician, engineer and artist, in which the deployment of the body and its senses in a professional techne did not carry the Athenian social stigma. While the superiority of sight endured in medieval thought through Aristotelian philosophy, it was ‘common knowledge at least to doctors that taste’ was, in fact, ‘superior’.Footnote 45 The integration of diagnostic taste was typically reflected in the perpetuation of urine analysis, a Sumerian–Babylonian practice that was further developed by the Hippocratic physicians and systematically used by their medieval successors.Footnote 46 The latter's deployment of urine wheels (Figure 1) that linked ‘the colours, smells and tastes of urine to various medical conditions’ prefigured the foundation of contemporary ‘metabonomics’.Footnote 47 It also prefigured the use of ‘aroma wheels’ by the present-day wine experts discussed later in this article.

Figure 1. Urine wheel from Epiphanie Medicorum by Ullrich Pinder (1506). The Royal Danish Library.

Outside medical practice, in which taste mediated a naturalist understanding of the sensed world, it is the Hippocratic physicians’ conception of health and its preservation through a regimen of appropriate foods and drinks that carried the social stigma of taste into the medieval era. During that era, Hippocratic medicine mutated into a dominant and much less naturalist scientific ideology that enabled new social hierarchies, born of the destabilizing imperial encounters of the times, to be enunciated and performed.

The theory of humours and the racial epistemologies of imperial taste

Tell me what you eat, I will tell you what you are.Footnote 48

No motto captures better than Brillat Savarin's 1825 aphorism the principle inhabiting the mind of Eurasian elites from late antiquity to the Western Renaissance, when the ontological, epistemological, aesthetic, moral and political meanings of taste became held together by the very materiality of food and its bodily receptacles. The story of what may be described as the first global scientific ideology begins with a Hippocratic variant of the ‘theory of humours’ from Nature of Man, a treatise attributed to Polybus, Hippocrates’ student and son-in-law.

‘The body of man’, wrote Polybus, ‘contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. This is what constitutes the nature of the body; this is the cause of disease or good health’.Footnote 49 The humours were loosely correlated with age but more importantly with the seasons, through a correspondence of the same pairs of natural qualities (hot, wet, cold, dry) that they shared with them. The theory posited that health derived from the balance of the humours and disease from their imbalance. A diet adapted to the seasons thus avoided or corrected the latter and thereby preserved or restored health.

Humourism remained marginal during the Hellenistic period, when the solidist view of the body, promoted by Alexandrian anatomy, focused medicine's attention on the organs.Footnote 50 This changed when Galen (AD 130–200) adopted and further developed the humoural theory, by adding a correspondence between the humours and the natural elements (air, fire, earth, water) and by suggesting a relationship between an individual's dominant humour and their character that had been absent as such from the Hippocratic version.Footnote 51

In the process of its diffusion and re-elaboration through Arabic and Latin translations throughout the medieval era, humourism became defined by a set of correspondences linking the humours to human life stages and to elements, qualities and cycles of nature, including the seasons, the lunar cycles and the zodiac.Footnote 52 Its most substantial transformation, however, was its doubling as a ‘theory of temperaments’ that was fully developed, well beyond Galen's basic equivalence, before the Renaissance began.Footnote 53 These elements are captured in Leonhardt Turneysser's illustration presented in Figure 2, one of many visualizations of the humoural principle found in European treatises since at least the twelfth century.

Figure 2. Illustration of the theory of four humours from Theosophie und Alchemie by Leonhardt Turneysser zum Thurn (1574). Deutsche Fotothek/Wikimedia.

Still conceived as open and porous to its environment, the body was now invested with social and moral meanings. Physical and spiritual health were equally viewed as dependent on the maintenance or restoration of the equilibria between the inside and the outside, giving much existential significance to what went in. Since different people had different humoural dispositions and temperaments, notably associated with their gender and social position, their regimen had to be adapted to their ‘fundamentally different gustative capability and constitution’: the choleric temperament of peasants required cold–wet diets of fish, cabbage and leeks to maintain humoural balance, while the phlegmatic royalty needed hot–dry foods like venison and wine.Footnote 54 What matters most to us is not the content of these correspondences, which varied substantially in the literature, but the logic of social distinction, opposition and stratification that they established.Footnote 55

Throughout antiquity, Galenic medicine operated within the cultural richness of the Roman Empire, centred on the products of the Mediterranean and the exercise regimes of its great cities.Footnote 56 The biotic world that sustained ancient culinary tastes and pharmacology originated in the diffusion of the first (Neolithic) ‘agricultural revolution’ from its earliest centre of origin in South West Asia to Europe and North Africa, which created a shared ‘package’ of domesticated crops and animals constituting the core of Mediterranean cuisine, itself formed and diffused by the expansions and exchanges of the ancient Mesopotamian and Mediterranean empires. This biotic universe was shaken twice in the following imperial ages, first with the ‘Islamic’ or ‘medieval Green Revolution’ carried by the Arab Umayyad and Abbasid imperial expansions (AD 700–1100), and subsequently by the ‘Columbian exchange’ of biota during the European colonization of the Americas starting in 1492.Footnote 57

Each of these episodes involved cross-continental translocations and exchanges of crops, animals, humans and their diets and tastes that forever changed the cultures of affected societies, bringing into contact cultural dispositions and food systems that had hitherto never historically coexisted.Footnote 58 The flexibility and capaciousness of Galenic medicine enabled the incorporation of new products such as tobacco, coffee, tea or chocolate that were brought into Europe in the early modern era, but also of new classes of people, now defined, in relation and in opposition to one another, by the signs reflecting their humoural and hence moral distinctions or failings, including their skin colour and their optimal diets, i.e. their natural tastes.Footnote 59

At the intersection of these two imperial episodes, the Iberian peninsula, where (Christian) Reconquista Spain replaced (Muslim) al-Andalus just as it launched its maritime power westwards, provides a perfect case study of how humourism mapped onto and performed political–ideological oppositions now expressed in explicitly racial terms. In this context, what one did not eat became as important as what one did, and ‘crossing culinary class lines’ was viewed as dangerous and fatal to both the body and the soul.Footnote 60 The humourism of empire thereby functioned as a theory of physical, cultural, social and moral contagion, as the tastes and foods of other, inferior and undesired people(s) were viewed not only as destabilizing agents but also as contaminants that could, as per the logic of sympathetic magic, transform one's very identity.

The foods most typically stigmatized and invested with this existential fear included the aubergine (eggplant) and later the tomato and maize (corn). The aubergine (Solanum melongena) originates from South and East Asia, where it was cultivated for thousands of years before the Abbasids brought it to the Levant in the late eighth or early ninth century, after which it diffused to Europe with the ‘medieval Green Revolution’.Footnote 61 Named pomme des Mours or ‘fruit of the Moors’ because it was a favourite of the Arabs there, it became a proxy for anti-Moorish and anti-Jewish sentiment in Europe. In Christian Spain, where Arab influence had made it a staple of Andalusian cuisine, it became specifically identified as a morisco or converso food.Footnote 62

Although early modern Iberian society did not endorse the essentialism characterizing later racial doctrines, the fact that ‘the physical body was thought to be generated in part through the ambient culture, and in particular through the diet’, made humourism a powerful conduit of racial ideology exemplified in discourses on the ‘Jewish body’, defined as ‘smelly and ill’ because of its accumulation of melancholy humours.Footnote 63 ‘Bad smell’, Rebecca Earle writes, was attributed ‘equally to the oily food [Jews] preferred to eat and the fact that they had not been baptized. Excessively oily “Jewish” dishes such as stewed aubergines thus helped create the smelly Jewish body at the same time as they signalled Jewish identity’.Footnote 64

The tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), originally identified as a type of aubergine and similarly named ‘fruit of the Moors’, was thereby equally rejected, and was additionally cursed by folkloric associations of the poisonous nightshade family with witchcraft.Footnote 65 These prejudices endured into the ninteenth century, as aubergines and tomatoes continued to be perceived as ‘low-class food[s] eaten by the Jews’ and therefore remained invisible in European markets as too ‘base’ for the Christian–European body.Footnote 66 The affirmation of non-Jewishness thus correlated with a rejection of these foods, articulated as a natural distaste for them, plainly expressed as natural and moral disgust.

The tomato is one of the ‘New World’ crops of the Columbian exchange that captured the imagination of European colonizers and became proxies for different forms of social distinction as they diffused across Europe, where some of them violently disrupted the moralized world of taste held together by a Europeanized Christian order. This was the world of the Bible, that repository of South West Asian agrarian culture out of which the first domesticated crops of the ‘Neolithic Revolution’ had culturally fossilized in what Fernand Braudel called the ‘eternal [Mediterranean] trinity’ of ‘wheat, olives, and vines’, and were subsequently dehistoricized, dogmatised and symbolled in the Catholic Church's rituals of the Eucharist (wheat and wine) and baptism (olive oil).Footnote 67

The spiritual crisis triggered by the Europeans’ violent arrival in the ‘New World’ is thoroughly dissected in The Body of the Conquistador, in which Earle reconstitutes the anxieties that gripped the humourist mind of the Spanish as they grappled not with the moral consequences of their conquest, but with the possible effects, on their body and soul, of the American crops that were unknown to the (South West Asian) Bible – how could they, then, be considered as ‘food’? The tastes that sustained the bodies and temperament of the phlegmatic natives could not suit the choleric Spaniards, but, more importantly, ‘Without the right foods Europeans would either die, as Columbus feared, or equally alarmingly, they might turn into Amerindians’: if it became accustomed to native tastes, the European body might be so transformed that it ‘ultimately ceased to be a European body at all’.Footnote 68

The settlers immediately expended their efforts into guaranteeing that ‘Old World’ crops were sent to the colonies to be consumed and cultivated there – a priority, Earle notes, that was ‘a thousand times more important than the introduction of chocolate into Europe’.Footnote 69 Since wheat bread, olive oil, fresh lamb and red wine constituted for them ‘the very essence of civilisation’, their replacement with local variants was akin to civilizational and spiritual collapse.Footnote 70 The crop that became most symbolic of this racialized ideology is maize (Zea mays), which the Spanish colonial administrators found more appealing for European cultivation than either quinoa or the potato, but constituted a troubling ‘other’ for the Catholic Church, who saw it as ‘anti-wheat’ or ‘un-wheat’ and hence as ‘alien and unchristian’.Footnote 71 Maize bread, if accepted as ‘bread’ at all, was claimed to be unsuitable for a Christian as the Church declared that maize, unlike wheat, could not undergo transubstantiation. Its consumption thereby guaranteed one's exclusion from the communion with Christ, which was nothing less than spiritual damnation.

The moral order that humourism thus mediated was the culmination of the process whereby ‘ethnic food’ and its associated tastes operate as ‘a field of action’ through which religious and ethnic boundaries and divisions are enunciated and performed.Footnote 72 As the globalization of American crops intensified, their incorporation into the political and cultural economy of modern European societies drove the constitution of new food systems that carried old societal divisions and erasures and consolidated new ones. Extracted from their native cultural and ecological contexts, these crops were individualized, invested with a distinctive epistemic attention and symbolic meaning, and assigned a different task in the new social order. The potato and the pineapple occupied the lowest and highest positions, respectively, in the natural, aesthetic, epistemic and moral hierarchies of the new age.Footnote 73

The taste and enlightenment of the few

We cannot form to ourselves a just idea of a pineapple, without having actually tasted it.Footnote 74

The transition to European ‘Enlightenment’ thought, characterized by a philosophical reaffirmation of Platonic body–mind dualism in a Cartesian form, operated a shift away from the ontological essentialism of food and repositioned taste within the domain and hierarchies of epistemological inquiry.Footnote 75 The latter had in the meantime been affected by a revival of ancient Greek scepticism, perspectivism in art and other trends in theological and medical literature that conspired to destabilize the secure position of the sense of vision.Footnote 76 This temporary ‘de-rationalization of sight’ coincided with the constitution of modern science, in which the sense of taste gained epistemic status as it reflected the ‘emphasis on probative experimentalism and a valorisation of first-hand, empirical experience’, which constituted the central tenets of the new natural philosophy, notably embodied in the newly established Royal Society in London.Footnote 77

However, as taste and the gustatory organs themselves became the objects of scientific investigation informed by mechanistic and corpuscular theories, the subjectivity of gustatory experience emerged again to disrupt its association with ‘authentic knowledge’. As Elizabeth Swann has shown, ‘in exploring how flavours are experienced by subjects … researchers came to understand tasting as fundamentally (rather than merely incidentally) subjective, comprising not an act of human apprehension, which may be more or less accurate, but a transformative interaction between self and world’.Footnote 78

Manifested experimentally as ‘radically unstable, manipulable, and variable’, the experience of taste was also revealed as weakly communicable across subjectivities.Footnote 79 The problems that the Royal Society faced, for example, in translating from Dutch the gustatory descriptions in Antoni van Leeuwenhoek's scientific reports thus cemented the notion that ‘flavours, resisting schematisation, generate metaphor’, and attested to ‘the difficulties of precisely capturing taste in language. Ultimately, the only way to know the flavour of something [was] to taste it; taste cleave[d] to experience, resisting language and report’.Footnote 80 These challenges were sufficient to devaluate taste within scientific inquiry and contributed to a return to vision as a more favourable sense for establishing the legitimacy of experimental science as a publicly witnessed, and thereby intersubjectively corroborated and authorized, social performance – albeit one exclusive to the consensus of experts, as political philosopher and critic of empiricism Thomas Hobbes perceptively noted.Footnote 81

In the equally empiricist field of moral philosophy, the epistemological status of gustatory taste was still asserted as the basis for knowledge of the external world as grounded in humans’ common sense experience. The elaboration of the empiricist principle in the seminal texts of British philosophers John Locke and David Hume nonetheless betrays a similarly exclusivist intersubjectivity reflecting an underlying ideology of social distinction. This ideology transpires in the specific taste that exemplified and illustrated their argument, namely the taste of the pineapple.Footnote 82 The peculiarity of this choice cannot be grasped from the texts alone, and requires, sociologically and intertextually, first to locate the position and status of the pineapple in the socio-economic, political, cultural and aesthetic context of the time.

Within the literature of the British Enlightenment, different crops mediated different concerns and social identities depending on their functional and symbolic meaning. As the foundation of national agriculture and a ‘state crop’ par excellence, wheat was invested with obvious economic significance and thus featured centrally in treatises, such as Adam Smith's, concerned with national production and wealth.Footnote 83 The potato, on the other hand, gained prominence in the political economy and science of nutrition, especially as it pertained to the physical fitness and (re)productive labour of the working classes.Footnote 84

Following a social stigma due to its American origin, its propagation method (from tubers, not seeds), and its ‘sickly’ appearance that associated it with the visually similar affliction of leprosy, the potato's social worth improved as its ‘caloric potential for supporting large numbers of people very cheaply was increasingly exploited by the growing population of western Europe’.Footnote 85 This would lead such prominent figures as Charles Darwin, who had brought back specimens of it from his voyage on the Beagle, to recommend it be reserved for the exclusive consumption of the poor.Footnote 86 As a forced alternative to the wheat appropriated by their English occupiers, the potato was further associated with the Irish people's subjected sociopolitical status. Entangled in their economic and political struggles of resistance and independence, it offered them a strategy of tax avoidance through its underground invisibility, while subsequently sealing their economic and demographic destinies when it was hit by blight.Footnote 87

All of these associations conspired to make the ‘humble’ or ‘lowly potato’ the marker of a negative social distinction – the kind precluding its prominence or presence in a philosophical treatise on taste, whether epistemological or aesthetic. The pineapple, on the other hand, was inscribed in a system of positive distinctions that systematically located it at the top of all domains and hierarchies of taste.Footnote 88

As soon as it was introduced into Europe by Spanish conquistadors, the pineapple became an object of adoration, its taste uniformly claimed as superior to anything European nobles’ papillae had ever encountered, notwithstanding the minor lament that it ruined the taste of their cherished wine.Footnote 89 With a shell displaying the mathematical perfection of divine proportion in the patterned alignment of its ‘eyes’ (in a Fibonacci series), and adorned by a natural ‘crown’ that gave it a distinctively royal aesthetic, the ‘king of fruits’ became ‘the true fruit of kings’, competitively paraded at European courts as a symbol of refinement and political power, and ‘the embodiment of everything the nobility liked to think that it stood for’.Footnote 90

At the time Locke wrote that one cannot ‘by words give anyone who has never tasted pineapple an idea of the [true] taste of that fruit’, the pineapple was still a rare sight in England, but a much-anticipated, much-advertised and much-celebrated phenomenon for the previous hundred years.Footnote 91 In the following decades it became the subject of intense epistemic attention, heightened by the challenges faced by Europeans trying to grow it in a climate not naturally favourable to its metabolism. Moved by ‘a spirit that amounted to obsession’, Dutch, French and British horticulturalists pioneered new technologies to achieve this expensive feat devoid of functional or economic value, culminating in the hothouses and pineries that constituted technological marvels of the time.Footnote 92 The association of the pineapple with botany and horticulture rather than agriculture – the domain of back-breaking wheat cultivation reserved to uneducated manual labourers – further signified its symbolic place within the socio-epistemic order of aristocratic rule.

Embodying simultaneously the distinctive character, aesthetic, power and taste of the aristocratic elite, the miraculous fruit's elevated social status afforded it an aesthetic persona of its own. No longer merely featured in paintings depicting aristocratic leisure life, the pineapple became the autonomous subject of its very own ‘portrait’, made in 1720 (Figure 3), a mere two decades before it appeared in Hume's Treatise of Human Nature. Commissioned by Sir Matthew Decker to celebrate his horticultural triumph – or rather, that of his Dutch gardener, Henry Telende – the painting displayed ‘a fully grown pineapple victoriously flourishing in an English landscape rather than a tropical Eden’ – a message the knowing elite of the time understood without any need for further visual context or the inclusion of any human actor or technical implement.Footnote 93

Figure 3. Pineapple grown in Sir Matthew Decker's garden at Richmond, Surrey, by Theodorus Netscher (1720). The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Soon thereafter, the pineapple's conquest of aristocratic interest and eccentricity culminated in the 4th Earl of Dunmore's addition, around 1777, of a structure in its shape atop his summerhouse near Falkirk, Scotland (Figure 4), affording him a delightful sight of the glasshouses and pineapple pits erected within his lavish property. ‘Intriguing’ and ‘bizarre’ is how the National Trust for Scotland, its current owner, describes this building, whose architect is unknown, and which adorns an estate far from major tourist routes and little mentioned even in the travel literature of the time.Footnote 94 What might appear to us as overblown eccentricity, or as the idiosyncratic taste of a man with a peculiar aesthetic, would have been fully intelligible to his contemporaries. As food writer Tasha Marks notes, ‘This is not just a pineapple as a decoration, but as a performative, architectural and symbolic marvel – a visual representation of class and power on a grand scale’.Footnote 95

Figure 4. The Pineapple House at Dunmore Park. Photograph: Kim Traynor; CC-BY-SA-3.0/Wikimedia.

How peculiar, then, that such an exclusivist object–symbol should be systematically chosen to illustrate the empirical foundations of universal human knowledge. If one could only ‘know’ the pineapple by tasting it, and if only a few ever had access to its taste, whose knowledge was thereby asserted as possible and secure? Locke's and Hume's own positions within the hierarchy of British society appear to provide a first answer to this question, on the assumption that they spoke of a taste they knew and hence of an object that was always ‘knowable’ to them and their peers. However, a careful textual analysis unravels a more complex and revealing meaning of that discursive move that gave the pineapple, ‘an object of particular symbolic saturation’, a central role in ‘one of the foundational moments in the history of taste’.Footnote 96

In his analysis of Locke's argument, Sean Silver shows that far from requiring its actual tasting – that is, an unmediated sense-perception of its flavour – Locke's assertion of the pineapple's ‘deliciousness’, which he claimed could only be enjoyed ‘in the Indies, where it is’, reveals its hypothetical status as an object of sensory judgement.Footnote 97 Locke's ‘authority to pronounce such an object delicious, and to desire it as a delicious object’, was mediated not by a sensory encounter with the real pineapple, which was inaccessible to him, but by ‘the discourse, the world of words, which structure and make desirable the anticipated experience of the chemical object itself’.Footnote 98

The imagined subject whose epistemic experience Locke described, then, already had ‘a taste for the pineapple before he ever [got] a taste of the pineapple’.Footnote 99 Silver's analysis is of profound significance as it reveals the intellectual trick that seamlessly anchored the unachievable epistemic security of gustatory taste in the socially secured hierarchy of cultural taste. As Silver concludes, empiricism solved the problem of gustatory knowledge by ‘provid[ing] the theoretical mechanics for concentrating on precisely what [was] knowable: on the interrelationships between cultural discourse and sensory experience in the absence of recourse to the object itself.’Footnote 100

This anchoring of sensory truth in the stabilized order of society was naturally carried over into empiricism's aesthetic philosophy as elaborated by Hume in the eighteenth century.Footnote 101 In the absence of a natural, universal standard against which individual aesthetic judgements could be measured and assessed, the social order provided the source for an alternative ‘standard of taste’, in the form of a small community of critics whose refined judgement and elevated understanding would rise above the plural and misguided subjectivities of ordinary tasters.Footnote 102 Enduring well beyond the collapse of the formal aristocratic hierarchies of its time, this Humean ideal has found a new social embodiment in the gustatory and aesthetic expertise of the twenty-first century.Footnote 103

Taste and social distinction after the Green Revolution

The best judge of the right styles of wine for your palate is you. There are no absolutes of right and wrong in wine appreciation.Footnote 104

Three developments have led to the rearrangement of the socio-epistemic landscape of taste in our time. First, the ‘Green Revolution’, originally launched during the ‘Cold War’ by the US philanthropic–scientific complex to save the wheat fields and agricultural economy of Mexico – one of the striking end results of the Columbian translocation – has enabled the uniformization and globalization of the major crops and domesticated animals sustaining humans’ growing world population and of the techno-suites involved in their industrial ‘production’. No longer exclusively attached to particular culinary traditions, these biota have become the basis of global food systems. Through its opening up of economic markets and its establishment of supply chains that bring local produce and products to supermarkets and to the homogenized menus of fast-food chains across the globe at affordable prices, world capitalism has further mediated a cultural globalization of local cuisines, culinary preferences and consumption habits across the class divisions of past times.

The latter process intersects with the post-war restructuring of societal stratifications, reflected in the emergence of new social classes and the fragmentation or blurring of past class boundaries and of the consumption patterns associated with them.Footnote 105 This phenomenon has been described as a ‘wider democratizing shift towards cultural “omnivorousness”’ whereby the ‘privileged middle and upper classes no longer consume only legitimate culture but … graze on both high and low culture’.Footnote 106 Sociological investigations have, however, repeatedly shown how ‘the ethos of omnivorousness’ often ‘veils distinction’, even in the most comparatively egalitarian societies, thereby confirming the renewal of the patterns of social demarcation that Bourdieu identified in 1960s France.Footnote 107

In a context where increasing varieties of consumer products have led to ‘diminishing contrasts’ in cultural distinctiveness, its markers have shifted to more eclectic products, lifestyles and status symbols manifesting the ‘tastes of freedom’ typical of those rich in cultural capital.Footnote 108 While food still operates as a proxy for racial identities and divisions through communities’ choice of ingredients, flavour preferences and cooking styles, it has become the privileged arena for the assertion of the new forms of distinction in which ‘food practices are intertwined with classed feelings of worth and disgust’.Footnote 109 Despite the secularization of culinary behaviour, food thus continues to be invested with moral meanings reminiscent of past social and religious ideologies, via the constitution of new ‘totems’ and ‘mythologies’ through which the pensée bourgeoise turns the quality contrasts assigned by the market into value signals of social significance.Footnote 110

In parallel to these transformations, the senses have become the object of a pluralist and professionalized domain of expertise devoid of a single holistic paradigm. The rise of the science of taste has benefited from the recent development of the science of smell, a sense that contributes to the perception of flavour through the phenomenon of retronasal olfaction.Footnote 111 The discovery of the olfactory receptors in 1991 was followed a decade later by the discovery of taste receptors in the tongue and, more recently, in the gut and other tissues.Footnote 112 These developments are reshaping centuries-old discussions about the material qualities of flavours, the nature and conditions of sense experience, the realities it captures, and the aesthetic experience it mediates, but also the relation of neurocognitive to social, cultural, psychological, emotional, evolutionary and contextual factors and processes of taste acquisition and differentiation.Footnote 113

Being now fragmented beyond any overarching, monopolistic discourse, the expertise on taste no longer exhibits the historical alignment between philosophical–scientific and social–cultural ideologies. The acknowledgement of the epistemic legitimacy and social worth of gastronomic experts since the eighteenth century and the recent rise of celebrity chefs have further expanded the domain of legitimate expertise, while reversing past social-exclusionist trends that denigrated the value of technical and bodily skills – a process that has nonetheless unequally benefited male chefs specifically.Footnote 114 And yet the convergence of social distinction and epistemic demarcation continues to operate, at the intersection of three countermovements to the transformations described above.

The first is a resistance to the homogenization of culinary cultures, best represented by the slow-food movement and its emphasis on place, seasonality, tradition and biodiversity, and on breeds and varieties less amenable to the standardized production paradigm of the ‘Green Revolution’.Footnote 115 This movement toward small-scale production and ‘authenticity’ converges with the positions of artisan food producers, who reject the uniformization of flavours and the artificiality, rapidity and codification of industrial food-making processes that annihilate the distinctive methods and flavour variations characteristic of slow, artisanal techniques.Footnote 116 Countries with such long-standing traditions have managed to protect them legally through ‘protected geographical indications’ (PGIs) and ‘denominations of origin’ (PDOs), which work ‘to provide a counter to the seemingly “placeless” and homogenized products of agri-capitalism by celebrating place-based connections and terroir’.Footnote 117

Terroir products offer optimal symbolic advantages to economic- and cultural-capital-rich consumers in search of new markers of social distinction. In the process whereby tastes gain ‘signaling value’ through their distinctiveness and costly adoption, cultural practices endowed with ‘a functional component … [are] harder to interpret as [social] signals’.Footnote 118 Foodstuffs associated with such utilitarian objectives as nutrition or health are thus less likely to be coopted aesthetically in the contexts of cultural globalization and democratization, which have now deprived past exotic items, like the once-prestigious pineapple, of their ‘social cachet’.Footnote 119 Culinary products of terroir, which can be detached from nutritional needs, asserted as art forms, and consumed aesthetically as haute cuisine, are therefore best coded as exclusionist consumption goods.Footnote 120 Among them, high-quality wines constitute the most secure anchors of contemporary social distinction.Footnote 121

The development of oenological science and neuroenology has contributed to a clear division between two fields of expertise. The first is ‘the science of wine’ as the knowledge of laboratory scientists who focus on the chemical, sensorial and neurological dimensions of taste and consciously refrain from articulating aesthetic judgements; the second is the knowledge of sommeliers and expert tasters from the industrial and gastronomic fields.Footnote 122 The latter knowledge is part of what Steven Shapin has described as the ‘sciences of subjectivity’, in which the community's intersubjective aesthetic consensus is expressed in a descriptive but often metaphorical language (cl)aiming to capture a wine's ‘objective’ qualities.Footnote 123 This universe of wine appreciation is inscribed in a complex socio-epistemic apparatus that delineates and regulates a field of action from which the generic and uncertain tastes, judgements and practices of the ordinary wine drinker depicted in the New Yorker's cartoon (Figure 5) are excluded as properly unqualified and hence inferior.

Figure 5. ‘I don't remember the name, but it had a taste that I liked’. Credit: Kaamran Hafeez/the New Yorker Collection/the Cartoon Bank.

The core of this apparatus is constituted by a small community of professional wine tasters who often display the heightened sense perceptions and neurological activity characteristic of ‘supertasters’.Footnote 124 In the absence of a material basis for linking aesthetic judgement to objective chemical properties, these experts follow regulated mechanisms that aim to bring into existence an object that is essentially not ‘given’, by reaching agreement about ‘the acceptable procedural ways that enable one to discuss, and to render public, divergent [aesthetic] evaluations’.Footnote 125 In this process, sommeliers typically ‘tend to reject all terms and phrasing concerning “judgement”’, arguing that tasting ‘should not be reduced to a matter of personal taste’ but rather concerned with ‘the objective analysis of the sensations’ produced by wine.Footnote 126 The tasting sheets and scorecards they use to construct consensus thereby operate as technologies of truth-making having the power to manifest taste as a unique ‘sixth sense’ shared neither by scientists nor by laypeople.

The social authority of professional wine tasters is supported by, and co-constitutive with, a wider institutional and economic apparatus that sets the criteria whereby quality is ordered according to its worth. Wine classifications, whether grounded in land/terroir and chateaux, like the French one, or in grape varieties and politically designated regions, as in US appellations, constitute the heart of this system. They create reputational labels that shape consumers' preferences and habits by imposing the industry's and the market's own socially constructed rationalization of the hierarchy of cultural values.Footnote 127

Social elites who can navigate this hierarchy by investing their economic, cultural and symbolic capital in the market of high-quality wines belong to the wider circle of connoisseurs who espouse the posture and aesthetics of professional wine tasters. Armed with similar technologies of intersubjective connoisseurship, such as the ‘wine aroma wheel’ that enables the production of objective truth out of relative cultural arbitrariness (Figure 6), their social display of expertise manifests distinction through the typical ‘restrictive’ mechanisms that accompany the use of status symbols. These mechanisms include the consumption of scarcity in the form of wines that are inaccessible to the average consumer, but also the cultivation of an art that denotes discipline, perseverance, restraint and substantial investment of unproductive labour in leisure time.Footnote 128 Mirroring the ‘wine talk’ of professional experts, their deployment of aesthetic judgements further signifies the privilege of those who can afford to take economic risk, such as betting on a ‘closed wine’ whose seeming ‘flatness’ or ‘dullness’ might hide ‘something here that isn't here yet’ and hence justifies a financial gamble on the possibility of future aesthetic reward.Footnote 129

Figure 6. Partial view of the Wine Aroma Wheel. Copyright 1990, 2002 A.C. Noble/Courtesy of www.winearomawheel.com.

The philosophy of taste constitutes the third ‘expertise’ pillar of the countermovement to the democratization of taste. Recent years have witnessed a regrouping of the philosophical tradition specifically around the knowledge, experience and aesthetics of wine, with such subfields as ‘epistenology’ and the ‘philosophy of wine’ representing a renewal of the philosophical project in the space left open by the science of taste.Footnote 130 Of particular interest within this literature are efforts to synthesize eighteenth-century philosophical perspectives on taste while avoiding the articulation of statements on its nature or objectivity that would be ruled out by the new scientific standards.

Philosophical discourse thus gravitates towards that other professional standard, Hume's ‘standard of taste’, as defined by ‘judges or critics who sho[w] delicacy of judgment; [are] free from prejudice; [can] draw on a wide range of experience for comparisons; [pay] due attention; and [are] unclouded by mood’.Footnote 131 Barry Smith's work is particularly revelatory of the intersection of this new philosophical ‘objectivism’, which combines the valued ability to differentiate and appreciate the ‘sense of a place and of culture’ as embodied in ‘the terroir’ with the expertise and aesthetics of professional wine tasters who represent the Humean ideal.Footnote 132 Acknowledging that there is ‘a kind of democracy of tasting’, since ‘everyone can experience wine by tasting it’, Smith argues that ‘thereafter the course of experience of the novice and the expert differs’, to the latter's epistemic advantage.Footnote 133

An objective philosophy of taste is possible, in other words, because the expert can indeed ‘really tell us a wine we do not like is exceptional, or that a wine we do like is of poor quality, or little interest’, for while ‘personal preferences cannot be criticised’,

it is not up to [individuals], or a mere matter of personal inclination, to determine who is the better painter or musician, or which is the better wine. There are standards by which we can judge a wine, or a musical score, or painting, to be better than another, and these reflect discernible properties of those objects, though it may take practice and experience to recognize them.Footnote 134

Through arguments similar to those that founded and reproduced ancient Greek epistemology and its authority to judge its own and everyone else's knowledge, the philosophy of wine appears, then, to be one of the domains in which social erasure still thrives, in the form of authoritative epistemological demarcation. Once social distinction is hidden from the discourse and praxis of taste, philosophers and refined drinkers can safely return to the old adage in vino, veritas, whereby wine, by loosening tongues and manners, reveals to others the (socially virgin) ‘truth’ of the taster and of wine's own ‘epistemological innocence’.Footnote 135

The many truths of taste

The history of taste is the fascinating story of a sense that is too powerful to be ignored or remain unexploited. Ever since the establishment of agrarian society and its exploitative model of collective subsistence, stable social orders have rested on the cultivation of a hierarchy of tastes that naturalizes the binaries of inequality into accepted preferences and celebrated identities. Whenever the legitimate truths and foundations of society are disrupted and thrown back into the open arena of egalitarian or anarchical contestation, taste re-emerges as the subversive anchor of new possibilities and desires, until it is disciplined again, tamed and folded into new hierarchies.

The history of taste simultaneously hints at its importance in elucidating the many entanglements of social and intellectual orders and of their respective mechanisms of truth-making. These entanglements have already been fruitfully dissected through a critique and reclaiming of the dominant sense of vision, notably in standpoint feminism's empowering counterepistemology.Footnote 136 This article has hopefully shown that the scientific and philosophical discourse on taste has been at least as intimately connected to the regulation and legitimation of social orders, and possibly in much less metaphorical ways than vision ever has. It is tempting further to excavate the specifically creative or emancipatory role the sense of taste has played throughout our social and political history, and to ask about the distinctive ‘truths’ that its undisciplined affirmation might offer us in the future.

As we rediscover the place of the sense of taste in the gustatory, epistemic and aesthetic orders of our past and present existence, we should also ask again why philosophy and science have so easily served and reproduced the same social distinctions and erasures that sustain social hierarchies.Footnote 137 Social constructionism interprets the alignment of social and epistemic orders as the manifestation of the ‘social-situatedness’ or ‘total-ideological’ nature of knowledge. It is, however, worth asking whether such an alignment might not be the symptom of a more profound structural connection, whereby epistemic and social orders sometimes need to coexist in harmony so they can exist at all.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Marieke Hendriksen and Alex Wragge-Morley for the opportunity to contribute a non-historian's perspective to this issue on taste. My thanks also go to Vicky Avery and Melissa Calaresu for inviting me to present some of the ideas elaborated in this paper at the Power, Promise, Politics: The Pineapple from Columbus to Del Monte conference (Cambridge, 2020). I am grateful to BJHS Themes editor Rohan Deb Roy and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful engagement with the article and their invaluable suggestions for improving its clarity for the journal's audience. I am also grateful to Nick Onuf for his comments on my use of materiality and physicality in this text, and to Rebecca Earle and David Nally for illuminating discussions on the politics of the potato. All images used in this article are published under an All Rights Reserved license and reproduced with the permission of the third parties. I thank Emma Darbyshire of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and Isabelle Lesschaeve of InnoVinum LLC for permissions to reproduce Figures 3 and 6 respectively. This article is part of the Global as Artefact (ARTEFACT) project, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 724451).