Refine search

Actions for selected content:

10 results

1 - Encountering the Third World

- from Part I - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 17-33

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part IV - A People’s Compassion

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 175-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Putting Down Roots

- from Part I - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 34-54

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part IV: - A People’s Compassion

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 175-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Encountering the Third World

- from Part I: - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 17-33

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Putting Down Roots

- from Part I: - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 34-54

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

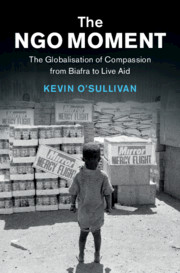

The NGO Moment

- The Globalisation of Compassion from Biafra to Live Aid

-

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021

4 - The Salvation Agenda

-

- Book:

- The Political Life of an Epidemic

- Published online:

- 10 January 2020

- Print publication:

- 30 January 2020, pp 123-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation