The London gold market was more than a local gold market. It played an important role in the international monetary system. In the 1960s, Charles Coombs, the vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, understood the issue. He wrote that the London gold market ‘represented a time bomb resting at the very foundation of the Bretton Woods system’.Footnote 1 Here I examine how this bomb was set up. US policymakers allowed the London gold market to reopen without fully understanding what the consequences would be. The reopening established a direct link between sterling and gold. Thereafter, sterling crises could potentially turn into gold crises. This would threaten international monetary stability. In the 1950s, the United States still had substantial gold reserves and capital controls. In the 1950s, US confidence in its gold reserves was unshakable. The Fed therefore allowed the United Kingdom to open the gold market on the assumption that it was a minor issue. As discussed in Chapter 10, the London gold market would eventually play a central role in the demise of the Gold Pool and the creation of a two-tier gold market. This in turn contributed to the end of the Bretton Woods system.

The London gold market reopened on 22 March 1954. This was a major event in the unfolding of the Bretton Woods system. The market had closed at the outbreak of the war in 1939.Footnote 2 This hiatus ‘deprived the international economy for fifteen years of one of its major institutions’, the Bank of England wrote in a later memorandum.Footnote 3 The BIS celebrated an ‘event which was not only of great potential significance but which also had an immediate influence, since it coincided with steps taken by several countries to normalise their foreign exchange systems’.Footnote 4

London was the central gold market during the Bretton Woods system. This important role was relatively new. Before the nineteenth century, the City was not at the centre of the gold trade. The leading global gold market moved from Genoa to Antwerp, then to Amsterdam before finally being established in London. Today London still offers the largest gold market. Despite London’s leading role, when the London gold market was not functional other markets took over. These included Zurich, Paris and Hong Kong.

During the fifteenth century, African gold was sent to Genoa, Florence, Venice and Milan, where it was traded.Footnote 5 Florence fixed the price twice a day. This feature would be replicated in the London market.Footnote 6 Later, Antwerp, a central place of trade in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, hosted African gold sales. The Belgian city was an early global market for gold and other commodities.Footnote 7 This might not have formally been an integrated central global gold market yet, but it involved the trading of gold globally. In 1596 a default by the Spanish state led to a wave of bankruptcies in Antwerp, which at the time was exposed to Spanish loans.Footnote 8 This led to Antwerp’s slow decline as a global financial centre and reopened the contest for leadership.

Amsterdam took a more prominent role as a financial centre in Europe in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It became the main market for silver and gold bullion. However, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 gave British finance a boost.Footnote 9 The shift of the leading gold market went through Moses Mocatta, a gold trader based in Amsterdam. Mocatta moved to London in 1671. At first gold was used as a way to pay for Mocatta’s diamond business.Footnote 10 Progressively, gold increased in importance and the Mocattas started a subsidiary gold market in Amsterdam, which would progressively expand.Footnote 11 In 1799, the Mocatta firm was still under the family’s control. It was now called Mocatta & Goldsmid, the name under which the firm operated during the Bretton Woods period.Footnote 12 Soon after the inauguration of the Bank of England in 1694, Abraham Mocatta, Moses’ son, became the Bank’s sole gold broker.Footnote 13

In 1810, a select committee of the House of Commons surveyed the London gold market because of the ‘High Price of Gold Bullion’.Footnote 14 With few participants, the market was subject to collusion. Mocatta & Goldsmid was the Bank’s only broker until 1840.Footnote 15 Later in the century, other brokers were permitted to enter the market. During the mid-eighteenth century, the London and Amsterdam bullion markets were highly integrated, as demonstrated by Pilar Nogues-Marco.Footnote 16 However, London took precedence over Amsterdam. The Bank Charter Act 1844 gave the London market an advantage by providing a ‘guaranteed market and a minimum purchase price for gold’.Footnote 17

Gold became key in international transactions in the mid-nineteenth century and the Bank of England played a central role in the international monetary system. The rapid increase in countries joining the Gold Standard meant the metal was essential to public finance worldwide. London would at this point play a leading role as a global gold market, being ‘the most liquid exchange for refined gold’.Footnote 18 Most newly minted gold was sold in London. The rules of the Gold Standard let gold flow freely in and out of the country. During this period, the Bank was the main dealer and acted with four others: Mocatta & Goldsmid, Sharps Wilkins, Pixley & Abell and Samuel Montagu & Co. Broker.Footnote 19 Most of these participants remained until the Bretton Woods period. Rothschild took the place of the Bank of England as market-marker after the First World War. Also, Sharps Wilkins and Pixley & Abell merged and the metallurgical firm Johnson Matthey joined.

1919 marked the creation of the London Gold Fixing, which would survive with interruptions until 2014.Footnote 20 Fixing was the process of fixing the price of gold once a day. At the start of the Second World War the market was officially closed and would not reopen until 1954.

Burgeoning Competition

During the closure of the London market (1939–54) Zurich emerged as a competitor. Other so-called free markets emerged. They offered gold priced often in dollars, notably in Beirut, Bangkok, Cairo, Kuwait, Macao, Milan, Montevideo, Tangier and Hong Kong. The IMF disapproved of these markets as they suggested that the official dollar price of gold was not credible. The Fund feared that these markets could destabilise currencies.Footnote 21 In 1950, in a telephone call between the New York Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, Sir George Bolton estimated that the market in free gold was around $60 million a month ($585 million in 2017 dollars). This represented a turnover of around $2–3 million a day, mainly in Montevideo, Paris, Milan and Zurich. Bolton commented on different markets, noting that ‘Beirut is just a tunnel in and out of the Middle East’ and that ‘Hong Kong is not a big factor’.Footnote 22 The Bank was aware of these free markets and was watching them closely in cooperation with the Fed. They drained international gold production and were a threat to the official gold price.

Coombs observed that these free markets were involved in private hoarding and did not cater to South African or Russian business.Footnote 23 Bott asserted that immediately after the war these markets offered substantial premia on the official gold price. In 1947, Bott reported prices reaching the equivalent of $80 an ounce. This led to arbitrage, as purchases ‘were made in New York and Mexico, where the price was around US$43 per ounce. It was then resold in India for pounds sterling at a price equivalent to around US$80’.Footnote 24 The BIS calculated that, from 1946 to 1953, out of a global production of $6,600 million, one-third was privately hoarded.Footnote 25 This put pressure on central banks. It could hinder global growth as it limited the amount of fiat currency that central banks, mainly the Fed, could issue. Remember that gold was backing the dollar.

Paris was another contender for hosting a global gold market. The city had a financial centre and the French government had ambitions to be at the centre of the international monetary system. But gold trading in Paris never managed to compete effectively with Zurich or London. The Paris market remained a national retail market. It opened on 13 February 1948, against the wishes of the IMF.Footnote 26 Foreigners were still forbidden from trading in this market until January 1967, but it reopened to foreigners because of French ambitions to make Paris a larger international player.Footnote 27 The 1967 opening of the market to foreigners did not increase gold sales. Rather, the market shrank from FF8.5 million average daily transactions in January 1967 almost halving to FF5.4 million in February and FF4 million in April.Footnote 28

The London market offered tighter spreads than Paris. As price depends on volume, it was difficult for Paris to catch up unless it increased its volume, which they it do only with better prices. The Fed put it simply: ‘[T]he low spread maintained by London bullion brokers between their buying and selling prices for gold makes London an attractive market for both buyers and sellers.’Footnote 29 Before the Second World War, London had a monopoly on South African gold sales, which increased transaction volumes.Footnote 30 After 1945, Zurich started to compete with the City for South African business but only seriously challenged London after the market temporarily closed in 1968.

The Gold Market Reopening

The reopening of the gold market created a direct link between sterling and the London gold market. This link would eventually put stress on the international monetary system. Any shock to the sterling/dollar market could influence the gold price via the London gold market. The gold price was the barometer of the Bretton Woods system.Footnote 31 Having the market in London created a transmission channel via sterling. Harvey defines the London gold market as a ‘status market’. She argues that beyond its market function, it was a global indicator of the price of gold.Footnote 32 Capie finds that the London gold price reflected ‘international sentiment on the dollar and so affected other currencies’.Footnote 33 Central banks did not engage in arbitrage but, as Eichengreen has established, if the price increased to more than $35 an ounce, it created an opportunity. Central banks could buy cheaper gold at the federal window and sell it for more in the London market.Footnote 34 This would arbitrage the price in London down but deplete US gold reserves in the process.

When the Bretton Woods system was set up, private ownership of gold was forbidden in the United States and Britain. The Bretton Woods articles of agreements did not mention private gold markets, suggesting they did not foresee that these would become an issue. Coombs wrote: ‘From the very beginning therefore, the official United States price of gold was vulnerable to speculative challenge by the private gold markets functioning abroad.’Footnote 35 Before the London market opened, some South African gold was sold directly in South Africa. The South African gold market was open to dealers from across the world, not only British.Footnote 36 Channelling all gold through London created an official price for gold, which investors could locate in the financial press. What was the political process that led to the opening of this market and why did the Federal Reserve not stop this potentially harmful market from opening?

The London gold market opened as a result of a power play between the United States, the IMF, the United Kingdom and South Africa. US officials were constrained by their commitment to buy gold at $35 an ounce at the gold window, the IMF saw gold markets as destabilising, the United Kingdom wanted to increase the international role of both London and sterling, while South Africa wanted to sell gold at a fair price. Surprisingly, the United States displayed only limited interest in all this.

In 1947, the IMF worried that newly minted gold would escape the control of monetary authorities. It issued a statement to encourage members to ‘take effective action to prevent external transactions in gold at premium prices’.Footnote 37 Sales at premium prices would disrupt exchange stability, the IMF believed. Its remarks were aimed at South Africa, which was trying to sell its gold at the best price. In 1947, the Bank of England had allowed a few licensed bullion dealers to trade gold as long as the premia on the official market did not exceed 1 per cent.Footnote 38 Following a request from the IMF, the British government withdrew this authorisation and refrained from developing a gold market in London.

British restraint was short-lived, as the French soon asked the IMF for a private gold market in Paris. It reluctantly agreed. The French were at odds with the IMF after trying to introduce a dual exchange rate system in 1948. They ended up leaving the Fund from 1948 to 1954 to fight what they thought were ‘Anglo-American abuses in the name of Bretton Woods’.Footnote 39 France having its own gold market meant that the IMF could no longer oppose a similar market opening in London.

South Africa also challenged the IMF. The country started selling gold directly to manufacturing and artistic markets at a premium. In 1949, the Wall Street Journal announced that South Africa managed ‘to sell 620,000 ounces of pure gold abroad at $38.52 an ounce’.Footnote 40 This represented about 5 per cent of the country’s annual production. The price was ‘$3.52 over the $35 an ounce price set by the U.S. and the International Monetary Fund’. While visiting South Africa, a delegation from the IMF noted how South Africa ‘used the argument that it is unreasonable for gold to remain at its present price while the price of all other commodities is greatly increased’.Footnote 41

Adjusting for inflation, profits from South African mines fell consistently. This put pressure on production and left large amounts of low-grade ore unworked. The BIS closely monitored South African productivity and profitability in its annual reports. Figure 5.1 illustrates costs and profits per tonne in South Africa from 1929 to 1958. The gaps in the chart are for the years the BIS did not collect data. The index compares prices with 1929, which is set at 100. Despite reducing costs by over 20 per cent in real terms after the war, profits never reached pre-war levels. During the 1950s, profits were almost 40 per cent lower than in 1929. The nominal anchor of the gold price at $35 an ounce was a problem for South African producers.

Figure 5.1. Gold costs and profits

Note: Index and inflation adjustment: author’s calculation.

In the 1950s, the United States controlled 64 per cent of the global gold reserves. US policymakers did not see the opening of the London gold market as a priority.Footnote 42 Allowing the market to open meant there would be two gold prices: A market price of gold in London and the official gold window price. Coombs revealed that despite seeing the risks, ‘in Washington the official mood was not to worry unduly over such distant problems’.Footnote 43 The US gold reserves at the time were high enough for this not to be a pressing issue. US policymakers were confident that their reserves were large enough to weather any crisis. Evidence of this confidence is found in a telephone conversation transcript between Bolton and Knoke. Knoke said: ‘We still have $23 billion in gold bars and even if present selling continues I see no danger of our [reserves] falling to a level where we might be scared.’Footnote 44 The 1960s would prove him wrong.

The United States did not see the gold market as an issue. It was ‘far too early to say much about these problems, many of which may be purely academic since they deal with eventualities in a rather uncertain future’.Footnote 45 The United States did not think that it could lose large amounts of gold reserves on this market. The explanation for this nonchalant attitude was two-fold. Reserves were high enough. Also, the Federal Reserve was highly sceptical of theories advanced by academics, mainly Triffin. Triffin argued that international liquidity would become a problem in the future. He had been arguing, from 1947 onwards, that a system based on gold would eventually run out of gold for central banks to use as reserves. This in turn would slow economic growth. The Fed was critical of Triffin. Other academics, such as Despres et al., believed that the system could survive with smaller US gold reserves as long as there was sufficient trust in the dollar.Footnote 46 This is how the system works today, with the dollar as an international reserve currency despite having little gold backing. In 1954, this debate was still in its infancy and the Fed did not start to worry about it until the late 1950s.

Russian gold sales in 1953 eased the price in offshore markets. The United States started to see ‘certain advantages in a free gold market, where South African and Russian supplies might well tend to outrun industrial and hoarding demand’.Footnote 47 Such a market could not be in New York if it were to accommodate Russian sales during the Cold War. When it came to the international monetary system, Russia and the United States had aligned interests. The Fed saw the opening of the market as an opportunity to improve global supply. Prior to the opening of the London market, the Bank of England had been dealing directly with the Russians for gold purchases.Footnote 48

The United Kingdom wanted to increase its standing in global finance. The Treasury issued a press release stating that before the war, ‘London was the premier centre of the world for dealings in gold’.Footnote 49 The reopening was meant to give ‘growing opportunities for traders, merchants and bankers, so that they may make the fullest contribution towards the increased overseas earnings’.Footnote 50 Schenk argues that the Bank of England hoped to restore ‘the status of the City of London and of sterling’ by reopening the gold market.Footnote 51 The sterling area, and mainly South Africa, was producing ‘about 60 per cent of world gold output outside the USSR’.Footnote 52 London’s position at the centre of the sterling area made it ‘a natural market for gold’.Footnote 53 The Fed for its part thought that this market would help London. It would be the ‘reestablishment of London as the center of the world gold trade and fuller use of the technical skills of its gold and foreign exchange dealers’.Footnote 54 The Fed was more than happy to let the market open and did not foresee any associated problems.

The London gold market opened as a result of South Africa’s willingness to sell gold and Britain’s interest in re-establishing the City as a leading trading centre. The IMF was opposed to opening the market, but US policymakers and Federal Reserve officials did not see it as an immediate threat. This was thanks to a favourable economic outlook in the United States and substantial gold reserves. With no opposition, the market reopened. It became the barometer for the health of the Bretton Woods system.Footnote 55 Later, it led to the creation of the Gold Pool in the early 1960s (see Chapter 7).

Behind Closed Doors

The gold market was consolidated around five main players in London. They processed all orders. It gave the Bank of England privileged access to the world’s most important gold market. Here I use new archives to explain the details of the functioning of the London gold market. This is important in order to understand what role the Bank played before the market became the focal point of the crisis in the international monetary system in 1961 (Chapter 7). The gold market was vital for international finance, but setting the gold price only involved a handful of individuals behind closed doors.

The gold market was an over-the-counter (OTC) market, which meant it did not have a physical location during the day, except for the fixing. It operated throughout the whole day but the biggest volume usually went through at the fixing. The fixing started each day at around 10.30 am in the offices of N. M. Rothschild & Sons and a price was generally set at 11 am. Rothschild chaired and hosted these meetings.Footnote 56 The process was as follows: The five dealers were all in communication with their respective trading rooms. First, the chairman would ‘suggest a price, in terms of shillings and pence down to a farthing; this price will be chosen at the level where it is thought that buyers and sellers are likely to be prepared to do business’. The price was then moved until ‘there are both buyers and sellers in evidence’.Footnote 57 When buyers and sellers had agreed on a price, this became the fixing price.

The market was composed of two merchant banks – Samuel Montagu & Co. and Rothschild – two gold brokers – Sharp Pixley & Co. and Mocatta and Goldsmid – and a metallurgical firm – Johnson Matthey. Demand came from central banks, industry and the arts, and hoarding. Supply was from new production, central bank sales, Russian sales and disposing of hoarding.Footnote 58

Figure 5.2 is a schematic representation of the market. Access to the market was only possible through one of the five main dealers. The Bank of England often played the role of agent for official third parties and was South Africa’s main dealer. Dealing with the Bank gave an informational advantage to customers. The Bank’s dealers processed most of the South African supply and were active in the market all day so they knew when to sell and how to avoid oversupply. Unsold gold was often absorbed into the reserves of the Exchange Equalisation Account at market price. This was an advantage as it did not move the market price and was a direct transaction between the Bank and South Africa.

Figure 5.2. Schematic representation of the London gold market

Note: For readability, not all possible arrows are present. For example, foreign central banks were able to deal directly with market-participating investment banks. Russia probably also dealt with Rothschilds and other dealers.

Rothschilds hosted the fixing and had the biggest market share. It also acted as an agent for the Bank. In May 1936, the governor suggested installing a direct line with the dealing room at Rothschilds. He was adamant to stress that it was not an endorsement. He wrote: ‘[A] private line be installed with Messrs. Rothschilds Bullion Room in view of the fact that the gold fixing takes place on their premises: this would in no way imply that Messrs. Rothschilds were regarded as being in a privileged position vis-à-vis the bank.’Footnote 59 In September 1938, the Bank decided that outside of fixing dealings, it should ‘no longer deal exclusively with Rothschilds’. The Bank would also deal with Mocatta & Goldsmid. This was not due to ‘dissatisfaction with the services most efficiently rendered by Rothschilds’.Footnote 60 It was in the interest of efficiency and competition. The Bank tried to maintain the appearance of a competitive market when Rothschilds was in a leading position.

If market demand came from the five main participants at the fixing, where did the supply of gold in the market come from? Figure 5.3 presents an estimate of world gold supply, combining new production and Russian sales. Data are from the BIS archive. Gold supply shows an upward trend until 1965, when Russian sales ceased and South African production stopped increasing. Russian sales were dependent on the country’s agricultural performance. When the country did not produce enough food (mainly wheat) to feed its population, it would sell gold to buy supplies from abroad. South African production depended on the price of gold. As the gold price never increased during the period, mining of lower ore tended to diminish. Equally, there were some productivity gains leading to more production. After 1965, South African production stagnated.

Figure 5.3. World gold production estimates by the BIS

Bank of England Operations

The Bank of England was responsible for the London gold market. Capie argues that after opening the gold market, the Bank of England intervened ‘to steady prices and to keep orderly markets’.Footnote 61 It was about ‘housekeeping’, just as the Bank was doing in other London markets. Here I analyse the operations of the Bank of England in the gold market before the creation of the Gold Pool. Despite not having any formal or informal mandate from the Fed, the Bank was defending gold–dollar parity at its own expense.

What was a typical day like for the gold dealers at the Bank of England? What follows is the dealers’ daily report for 15 March 1956, a typical day. The report read: ‘Gold was fixed ½ d. lower at 249s.4.½d. at which price we sold 20 South African bars to the market and took 160 for H.M.T. The international price was marginally firmer at $34.96 ½. Against dollars we bought 240 bars from Montagus (= the Russians) and sold 120 to the Italians.’Footnote 62

What does this mean in plain English? On that day, the Bank sold twenty bars of South African gold at a market price of 249 shillings 4½ pence an ounce of gold.Footnote 63 That amount is equivalent to $34.916, below the official Bretton Woods price. It bought 160 bars for the Treasury (or H.M.T.). This gold was for the reserves of the Exchange Equalisation Account. Remember that the account belonged to the Treasury but was the United Kingdom’s reserve account. Still, on that day, the Bank acted as an agent for the Italians, who wanted 120 gold bars. This was part of their customer business, where they acted as an agent. The bank also bought gold from Samuel Montagu & Co. Montagu was one of the five key market players. On this occasion, Montagu sold gold on behalf of Russia. This was one of the key functions of the gold market. It allowed Russian gold to relieve price pressure on gold in London. The Russians would always supply gold, never buy it.

The main quote for the gold price was always in sterling, but all market participants were aware of the equivalent dollar price. At $34.96½ on the quote analysed earlier, the price was lower than the gold window price of $35 an ounce. This explains why the Bank of England offered only twenty gold bars from South Africa to the market. It took all the rest for its customers and for the EEA. If the price of gold were higher, it would have sold all the gold to the market to meet the demand. The Bank was managing the price of gold to stay around the Bretton Woods official price at the gold window at $35 an ounce.

This lower price on that day was detrimental for South Africa, which wanted to maximise profit, but beneficial for the Treasury, which was able to buy gold cheaply. In a letter to the Federal Reserve, the Bank explained this selling process. The South African Reserve Bank would ‘ship gold regularly to London and give us, as their agents, an order each week to dispose of a specified amount of the gold we hold for them’. Marketing of gold was the Bank’s role. It managed ‘both the timing of the sales and whether the gold is offered in the market or sold to other purchasers’.Footnote 64 The Bank decided whether to offer it to other central banks of the counter or to sell it to the market. It almost acted as a market maker.

Figure 5.4 summarises Bank of England operations in the gold market using data from internal daily dealers’ reports. The data are presented for the first time here. The Bank classified dealings as ‘customer’ operations (shown here in grey) or ‘market’ operations (in black). The distinction was internal for the Bank. To market participants, all operations looked the same. After 1957, however, the Bank stopped distinguishing between the two and reported all operations in aggregated figures (also in black). In 1956, the Bank was still treating operations for South Africa and the Treasury/EEA as customer operations before aggregating them in March 1957. This was arguably a shift in the way the Bank understood its mission. It changed from that of a simple agent to a more holistic role. It was ensuring that the price was where the Bank wanted it to be: somewhere between $35.08 and $35.20 an ounce. This role would be enhanced with the introduction of the Gold Pool. At that point, this became the official mission of the Bank of England.

Figure 5.4. Market and customer gold transactions by the Bank of England, 1954–59

The official Bretton Woods gold price was $35 an ounce. This is the price at which the Fed sold gold at the Fed window. There was a tax imposed by the US Treasury of 0.25 per cent. Adding the tax made the official price $35.0875. At this price, the gold would be delivered in New York. If investors then wanted to insure and transport the gold from New York to London, there were additional costs. Taking into account insurance and transport costs between London and New York, the price of gold in London from the Fed window was $35.20 an ounce. Above this price central banks could make an arbitrage profit. They could buy gold in New York and sell it in London. The Bank of England wanted to keep the price below $35.20 an ounce to avoid central banks speculating against the Fed. With a price of say $35.21, a central bank could buy gold at $35.0875 at the Fed and sell it on the London market, covering transport costs and making $0.01 profit an ounce. Even if central banks were unlikely to engage in arbitrage against the United States, the possibility of arbitrage sent a bad signal to market participants. It would cast doubt on the ability of the United States to maintain gold parity. In the long run, this would threaten the credibility of Bretton Woods.

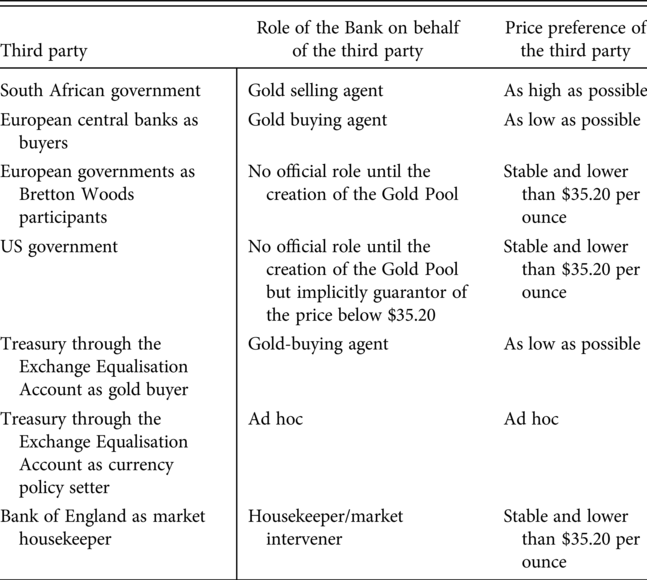

As we have seen, the Bank had many hats: Sometimes agent for the Italians, at other times helping the Treasury build reserves. The Bank marketed South African gold. It even took responsibility for the global gold price. The complex position of the Bank is summarised in Table 5.1. The table shows the Bank’s preference for the gold price, depending on which hat it wore. The Bank had an incentive to keep the price from dropping in order not to lose South African business. But it also had an incentive not to let the price soar to keep the international monetary system from breaking down.

Table 5.1. Price preferences of the various market actors

| Third party | Role of the Bank on behalf of the third party | Price preference of the third party |

|---|---|---|

| South African government | Gold selling agent | As high as possible |

| European central banks as buyers | Gold buying agent | As low as possible |

| European governments as Bretton Woods participants | No official role until the creation of the Gold Pool | Stable and lower than $35.20 per ounce |

| US government | No official role until the creation of the Gold Pool but implicitly guarantor of the price below $35.20 | Stable and lower than $35.20 per ounce |

| Treasury through the Exchange Equalisation Account as gold buyer | Gold-buying agent | As low as possible |

| Treasury through the Exchange Equalisation Account as currency policy setter | Ad hoc | Ad hoc |

| Bank of England as market housekeeper | Housekeeper/market intervener | Stable and lower than $35.20 per ounce |

Only South Africa had an incentive to maintain a high gold price. It provided most of the world’s gold supply and could threaten to sell its gold elsewhere. The Bank had to manage the conflicting interest of South Africa against its other customers. Russia and other producers shared South Africa’s interest in a high price. They had the disadvantage not to deal with the Bank of England directly. In the context of the Cold War, Russia had little diplomatic clout. It was obliged to participate passively in this market. Its transactions were done through private dealers, as we have seen.

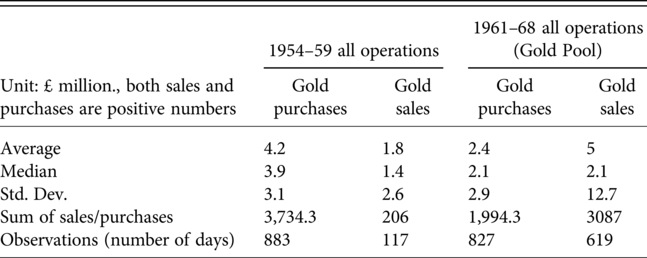

Table 5.2 categorises sales and purchase operations separately for two distinct periods: pre-convertibility and the Gold Pool period. Purchases are operations that increase the Bank’s net gold position or transactions on behalf of customers. Sales are when the Bank sells gold against sterling or dollars. Apart from a handful of operations, most sales operations were on the Bank’s own account and not for customers. Sales should mitigate market pressure by reducing the gold price.

Table 5.2. Bank of England gold operations in $ million

| 1954–59 all operations | 1961–68 all operations (Gold Pool) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit: £ million., both sales and purchases are positive numbers | Gold purchases | Gold sales | Gold purchases | Gold sales |

| Average | 4.2 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 5 |

| Median | 3.9 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Std. Dev. | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 12.7 |

| Sum of sales/purchases | 3,734.3 | 206 | 1,994.3 | 3087 |

| Observations (number of days) | 883 | 117 | 827 | 619 |

Note: Sales and purchases are presented as positive numbers.

Before 1959 convertibility, 88 per cent of the Bank’s operations were net gold purchases. The Bank was not worried about an increase in the price and could buy gold on most days.Footnote 65 If buying was too strong, the price would rise and, therefore, the Bank joining buyers is a sign that the price was under control. After convertibility, purchases represented only 57 per cent of operations. Convertibility forced the Bank to sell larger amounts of gold on the market. Operations rose from $1.8 to $5 million a day on average. At the same time, the average purchase the Bank was able to make on a given day was almost halved. This meant that market conditions after convertibility were worse. The Bank was forced to sell more gold and was able to buy less. Before convertibility, the Bank spent just $206 million to defend the gold price in London from 1954 to 1959. After convertibility, the Gold Pool was forced to sell fourteen times more (just over $3 billion) from 1961 to 1968. This explains why it was no longer willing to manage the London gold price by itself but asked for US assistance. This led to the creation of the Gold Pool, the subject of Chapter 7.

London had been the leading global gold market since the mid-nineteenth century. British authorities had a strong desire to reopen this market after the Second World War. The context of Bretton Woods meant that the market was to play a central role in determining the credibility of the dollar peg to gold. It was going to be a barometer for the entire Bretton Woods system. If the dollar price of gold in London increased, it highlighted that the official gold dollar parity at the gold window was not credible. London became important for the international monetary system. It was the main international gold market, while US citizens were prevented from owning gold under the terms of the Gold Reserve Act 1934. As shown, US policymakers did not fully grasp the potential consequences of the reopening of the gold market. The IMF, on the other hand, did see it as a threat to the stability of the international monetary system. Bank of England market operations in the gold market until 1959 mainly involved purchases. There was little upward pressure on the price of gold. Convertibility and freer capital flows thereafter drastically increased pressure on the London gold market. In the early 1960s, market forces would prove too strong for the Bank of England to manage alone. It led to the creation of the Gold Pool, as we will see in Chapter 7. The first crisis came in October 1960 with the US presidential election and John F. Kennedy’s pledge to ‘get America moving again’. This was viewed as an ‘inflationary policy that might force the United States to devalue its currency’.Footnote 66