One way in which art encourages an understanding of the revolutions that exceeds perceptions of them in simplistic binary terms of success or failure is by exploring the space between or beyond things or states. Some works, for example, examine the relationship between presence and absence. Safaa Erruas explores the Uprisings across North Africa and the Middle East by embroidering the flags of the twenty-two member states of the Arab League in tiny white pearls on white cotton paper in her installation Les Drapeaux (2011–12; Figure 1.1). Sonia Kallel uses an alternative colourless organic material – jute fibre – to evoke corporeal absence in her response to the Tunisian revolution, Which Dress for Tomorrow? (2011; Figure 1.2). Transparent screens or windows are employed by Aïcha Filali to support photographic cut-outs of ordinary Tunisians in L’Angle mort (2012–13, a work she began before the Tunisian uprising, in 2010; Figure 1.3). Shada Safadi also uses multiple clear plastic screens, but for etching distorted human forms commemorating the loss of numerous Syrian civilians in Promises (2012; Figure 1.4). Other works might be seen to explore the space between dimensions through, for example, two-dimensional discs which evoke three-dimensionality when in motion. Videos of spinning arabesques are employed in contrasting ways to reflect on the Tunisian revolution and/or the wider ‘Arab Spring’ in Kossentini’s Le Printemps arabe (2011) and Heaven or Hell (2012; Figure 0.1) and Mounir Fatmi’s Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine – la chute (2012). This range of gallery-based works exemplifies the more poetic responses to the revolutions. These works are, nonetheless, clearly anchored in relation to specific contexts through visual or verbal elements. Indeed, the space they create allows for alternative voices and visions of revolution between or beyond tangible or clearly legible, but static and reductive, icons. These works contrast notably with some of the more explicitly political – and, at times, controversial – participatory art in public spaces that I analyse in Chapters 3 and 4.Footnote 1 Yet, they similarly evoke a dynamic between stability and instability and, often, control and contingency.

Figure 1.1 Safaa Erruas, Les Drapeaux (2011–12), Institut du Monde Arabe.

Figure 1.2 Sonia Kallel, Which Dress for Tomorrow? (2011), Centre National d’Art Vivant de Tunis.

Figure 1.3 Aïcha Filali, L’Angle mort (2012–13), IFA Gallery Berlin.

Figure 1.4 Shada Safadi, Promises (2012), The Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA 2012) exhibition, A. M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah.

In this chapter I analyse this central dynamic through the concept and practice of ‘infra-thin critique’. I show how certain art exploring the revolutions resonates, to some extent, with French artist Marcel Duchamp’s notion of the ‘inframince’ (‘infra-thin’), which he developed in the 1930s. Duchamp (1887–1968) is often viewed by art historians as the most radically original artist of the twentieth century. His pioneering approach to thinking about art and the art process – particularly in relation to the use of replication, appropriation, chance and ambivalence – has had a profound influence on artists across the world (see, for example, Ades et al., Reference Ades, Cox and Hopkins1999; Naumann, Reference Naumann1999; Cros, Reference Cros and Rehberg2006). My intention, as I indicated in the Introduction, is not to suggest that this art is simply derivative, or that criticism should ‘turn back’ to European modernism to seek tools for analysis. These artists do not draw intentionally on the infra-thin, though some do engage directly, and ironically, with Duchamp’s work, and it is their work that inspired my critical approach.Footnote 2 I argue, rather, that such art resonates with the dynamics of the infra-thin, while it adapts a range of transnational (particularly Arabic and/or European) modernist or enduring local practices, or develops new practices, for the purposes of resistance. It continues what critics have shown to be the transcultural process of transformation and exchange which has long been central to variants of modernism in different locations and times, including early twentieth-century European modernism (Drewal, Reference Downey2013; Salami and Blackmun Visonà, Reference Salami, Blackmun Visonà, Salami and Visonà2013). Holding onto the term ‘infra-thin’ serves to highlight not only the, at times, striking resonances of these works with this notion but also their differences from it, given their engagement with local or diversely regional practices and specific contexts of revolution.

Marcel Duchamp’s notion of the infra-thin refers playfully – often humorously – to the almost imperceptible separation, and passage, between two things. Among the examples provided by the artist are: the warmth of a seat that has just been left, the reflection from a mirror or glass, people who pass through the metro gates at the very last moment, the sound made by felt trousers as the legs rub together when walking, tobacco smoke when it smells also of the mouth that exhales it, or the passage between dimensions (Duchamp, Reference Dunoyer, La Luna, Machghoul, Ouissi, Thullier, Ben Ayed and Blaiech1999 [1945]: 19–36). The recurrent emphasis, in Duchamp’s notes, on sensorial elements other than the visual is in keeping with his resistance to both academic and avant-garde art – especially painting – and the privileged status it gave to the ocular. Duchamp’s notion of the infra-thin emerges in his practice through the use of elements such as moulds and casts (between presence and absence), the portraits of the artist as his female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, or his ready-mades (between functional object and work of art).Footnote 3 The infra-thin refers not only to the interval or nuance that separates material objects or dimensions, but also concepts, such as sameness and similarity, or signifier and signified.Footnote 4

Art exploring the revolutions, as I indicated in the Introduction, avoids constructing a hierarchy between cultures and communities and, at the other extreme, reductively unifying them (for example, via the neo-colonial discourse of ‘democracy’ as a ‘Western’ ideal). It does so by simultaneously bringing together, or evoking, different languages, states or identities, and holding them in tension. Duchamp is not known to have thought about the infra-thin in relation to encounters between cultures or communities. Yet, this notion offers a means of thinking about such encounters in ways that avoid the extremes of hierarchisation and reductive unification. This is because numerous instances of the infra-thin point in alternative directions while also materialising the ‘hinge’ that connects them.Footnote 5 Specific states or identities are brought together, or simultaneously evoked, and are held in tension, rather than being fused to produce a synthesis or hybrid ‘third’ entity.Footnote 6 The infra-thin renders perceptible the separation between or beyond such states or identities to allow the singular to emerge.Footnote 7 Such a dynamic can frequently be discerned in art exploring the revolutions. At the same time, in such works, this dynamic is ‘anchored’ in relation to a particular context and specifically creates an alternative to iconic visual languages of revolution. It brings to mind Rami G. Khouri’s call for humility and patience in attempting to understand the complex Uprisings beyond instantaneous media responses (Khouri, Reference Khouri, Al-Sumait, Lenze and Hudson2014: 14). Through what I am calling an ‘infra-thin critique’, the art I analyse in this chapter creates a space and a moment in time for reflection on specific local experiences of revolt or on the wider complex phenomenon of the Uprisings.

In this chapter I address two recurrent forms of infra-thin critique. Ambivalence between sensorial and dimensional elements is discussed with reference to Nicène Kossentini’s video, Le Printemps arabe (2011), and her later version of this work, a video and sound installation, Heaven or Hell (2012), as well as Mounir Fatmi’s Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine – la chute (2012). I argue that Kossentini’s and Fatmi’s works demonstrate how a multidirectional, infra-thin critique can be evoked through dimensional and sensorial shifts, and particularly through the use of kinesis. Both Kossentini and Fatmi engage directly and ironically with Duchamp’s work by reappropriating his renowned spinning discs, or ‘Rotoreliefs’ – some of the first examples of kinetic sculpture – and combining them with Islamic cultural forms, reminiscent of Tunisian and other Arabic modernisms. I demonstrate that in contrasting ways a transcultural visual symbol is exceeded in their works, and a space for alternative voices and visions is evoked, through the use of specific aspects of the infra-thin: the passage between empty sounds and abstract referential meaning, the passage between the second and third dimension via movement, and the evocation of a fourth dimension through multidirectional outward expansion. In these ways the videos evoke both fragility and resistance to diverse essentialising views of the revolutions in a transnational context and simultaneously, in Kossentini’s installations, in post-2010 Tunisia.

Such an alternative space is materialised through diverse manifestations of a ‘poetics of absence’. I examine the contrasting ways in which an infra-thin critique emerges through: practices of layering white on white in Safaa Erruas’s Les Drapeaux (2011–12); evocations of corporeal absence through the use of sculptural ‘casts’ resembling skin in Sonia Kallel’s Which Dress for Tomorrow? (2011); and the use of transparent screens, combined with natural or artificial light, in Aïcha Filali’s L’Angle mort (2012–13) and Shada Safadi’s Promises (2012). Erruas’s process of weaving in white is a form of mourning and her delicate flags evoke the fragility of nations across North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Kallel’s similarly colourless ball of jute suspended by metal wires (or tied with hemp string) conjures, by contrast, a constrained body and encourages reflection on Tunisia’s uncertain future beyond the revolution. Yet, both can also be seen to resist essentialising perceptions of countries in the process of revolution, including clichés surrounding women. Filali, like Kallel and Kossentini, engages with the specific context of Tunisia. Her back-views of ordinary people in the street privilege the everyday over iconic images of Tunisia and the revolution. Safadi’s poignant installation presents a marked divergence in its sombre tone, mourning and commemorating those lost in the civil war in Syria. I show how both installations, nonetheless, use transparent screens, human figures and light to create a space for alternative visions of ‘revolution’ and to engage the spectators physically and emotionally.

These works use different media, materials and techniques to convey what critics such as Fahed Al-Sumait et al. have insisted is the complex and transitional nature of the Arab Uprisings (Reference Al-Sumait, Lenze, Hudson, Al-Sumait, Lenze and Hudson2014a: 20). They highlight the importance of distinct states of ongoing revolution, from what scholars have shown to be the ambivalence and turbulence of nascent democracy in Tunisia (Dakhlia, Reference Dakhlia2011; Gana, Reference Gana and Gana2013) to what rapidly became a complex and intractable civil war in Syria. The Syrian uprising, unfolding in more complicated circumstances, ‘[went] beyond its own internal dynamics to become an integral part of the region’s major geopolitical conflicts’, as Raed Safadi and Simon Neaime have detailed (Reference Safadi, Neaime, Elbadawi and Madkisi2016: 187–8; see also Hashemi and Postel, Reference Hashemi, Postel, Hashemi and Postel2013a: 6–7). At the same time, I argue, these works converge in their aesthetics and in their evocation of an ‘infra-thin critique’. I consider this art, and this critical tool, in relation to wider aesthetics of resistance. This diverse corpus resonates with the infra-thin. At the same time, I argue, it innovatively combines existing transnational – including local and regional – practices, or develops alternative means of rendering visible the invisible, in ways that question reductive internal and external views of cultures, communities and revolutions.

Transnationalising the Infra-thin: Revolutionary Arabesques and Le Printemps arabe

One way in which the infra-thin passage between dimensions emerges in the work of Duchamp is through the use of rotating discs. His ‘Rotoreliefs’, though two-dimensional, give an illusion of three-dimensional relief. Early versions of these spiralling animated drawings were depicted in Duchamp’s experimental film, Anémic Cinéma (1926). These Rotoreliefs were alternated with nine revolving discs displaying whirling alliterative puns, such as: ‘Bains de gros thé pour grains de beauté sans trop de bengué’, or: ‘Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis.’ Alternative instances of the infra-thin frequently coexist in the same work. These absurd, ludic phrases can be seen in terms of a verbal instance of the infra-thin in their indication of the passage between empty sounds and abstract referential meaning, between signifier and signified. A further example can be discerned in the (partial) mirror reversal in the film’s title, which is reminiscent of Duchamp’s recurrent reference to mirrors, glass and reflections as generators of the infra-thin: ‘Réflexion de miroir – ou de verre – plan convexe’ (‘Reflection of mirror – or of glass – convex surface’) (note 9r, 22). He relates mirrors and reflections, moreover, to the passage between dimensions: ‘Miroir et réflexion dans le miroir maximum de ce passage de la 2e à la 3e dimension’ (‘Mirror and reflection in the mirror maximum of this passage from the second to the third dimension’) (Footnote note 46, Footnote 36). The film’s opening shot can be seen to allude visually to this passage: the two capitalised words of the title seem almost to be hinged together, the ‘c’ of both appearing nearly to touch an imaginary mirror. This shot – like the dimensionally ambivalent discs it anticipates – evokes visually an infra-thin separation between surface and depth, which is explored verbally through Duchamp’s sonorous language.

Two versions of a work by Tunis-based Nicène Kossentini – her video, Le Printemps arabe (2011, 6′), and her later version of this work, a video and sound installation, Heaven or Hell (2012, 6′) – explicitly rework Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma to explore the uncertainties surrounding the Tunisian revolution and the wider ‘Arab Spring’ (Figure 0.1). Le Printemps arabe (2011) displays a rotating circular arabesque which gradually loses cohesion. Patterns within the disc spin in alternative directions at different speeds, as the white border gradually shifts away and disappears, allowing the individual parts to scatter chaotically to the edges of the frame. This visual explosion resonates with Tahar Ben Jelloun’s figurative image of the Arab Uprisings: ‘La patience des peuples a ses limites, le vase devait finir par déborder: il s’est brisé en mille morceaux’ (‘There are limits to people’s patience; the vase had eventually to overflow: it shattered into a thousand pieces’) (Ben Jelloun, Reference Ben Jelloun2011: 12). This process of fragmentation communicates revolutionary liberation, but also the loss of a secure sense of social and cultural identity. Shots of the fragmenting arabesque are interspersed with others displaying rotating discs on which isolated Arabic words are written in a spiral. Each of the five discs presents a selection of disconnected words and expressions associated with hell and paradise, taken from the Qur’an (which appear translated into French or transcribed phonetically in the corner of the screen) – ‘jardins, paradis, délices, faveurs, le bien, ruisseaux, Salsabil, haut placé, vive, source’ (‘gardens, paradise, delights, favours, the good, streams, well’) (disc 1); ‘subissez, jetez, carcans, bruyantes, attisé, gardiens de vergers, vignes, liqueurs, cachetées, surélevés, à leur journée, étalé, coupe, débordante’ (‘endure, throw away, constraints, noisy, stirred up, orchard caretakers, vines, liquors, sealed, raised, on their day, spread out, bowl, overflowing’) (disc 2); ‘ne leur parle pas, malédiction, Saqar, flambée, flammes ardentes’ (‘don’t speak to them, curse, Hell, burnt, burning flames’) (disc 5).Footnote 8 The images of the hypnotic rotating discs are accompanied by the similarly incessant sound of rhythmic clapping, reminiscent of a revolutionary march.

In Kossentini’s work, dimensional and verbal ambivalence are combined with transcultural tension for the purposes of a multidirectional critique. In bringing together the Rotorelief and an arabesque, Kossentini produces a form that comes to represent neo-imperialism, as well as political singularity and apparent social unity within Arab countries such as Tunisia (this work can be read as evocative both of the wider Arab Uprisings and of the specific case of the Tunisian revolution, particularly given its exhibition at ‘Dégagements … La Tunisie un an après’).Footnote 9 Le Printemps arabe evokes not only political and social upheaval and transition but also an artistic revolution. Kossentini perceives the alternation in Le Printemps arabe between rotating discs inscribed with Arabic words, or formed to resemble an arabesque pattern, ‘comme une métaphore sur un “art contemporain arabe” qui oscille entre les couleurs vives des racines et les voix saturées des horizons’ (‘as a metaphor for a “contemporary Arab art”, which oscillates between the bright colours of its past and the myriad voices of its future’) (Kossentini, 2012).Footnote 10 The explicit reappropriation of the French artist Duchamp calls for a more inclusive history of art; it critiques the persistent marginalisation of works that explore Arabic forms as ‘traditional’ or ‘decorative’ (Rachida Triki has highlighted the importance for Maghrebi art of distinguishing itself from the label ‘contemporary Arab art’ established by the ‘northern’ art market system (Triki, Reference Triki2017); see also Ben Soltane, Reference Ben Soltane, Barsch, Bruckbauer and Baatsch2012).Footnote 11 This visual manoeuvre can equally be seen to critique the tendency to essentialise and exoticise Tunisia, which persisted in both French and Tunisian political rhetoric until the very end of Ben Ali’s leadership; it indicates the entanglement of French and Maghrebi histories more widely. It is also reminiscent of the history of Tunisian artists’ distinctive critical engagements with the regional tendency to combine modern art with enduring Arabic forms such as the arabesque and calligraphy, particularly since the 1970s (see Tlili, Reference Tlili, Barsch, Bruckbauer and Baatsch2012; Nakhli, Reference Nakhli2017).Footnote 12 Yet, the evocation of an ‘art contemporain arabe’ appears simultaneously to articulate liberation from the former censorship of art and culture in Tunisia, as part of the work’s more general opposition to the political and social constraints associated with the former regime. Viewed in 2012, the work could also be seen to contest new forms of extremism and attempts at censorship in politics and society as well as in art. In Kossentini’s work the circular form functions, like an icon, to represent political singularity and apparent social unity within Arab countries such as Tunisia, as well as forms of ‘neo-imperialism’ via the global art market – through its trends and its curatorial practices – and through French and European foreign policy. The circular form emerges in this work as a visual language of domination in both ‘Western’ and ‘Arab’ cultures and, moreover, of complicity between the French government and that of Ben Ali.

In Kossentini’s work, dimensional ambivalence is ironically exacerbated through fragmentation. The visual symbol of alternative ‘centres’ of power is exceeded through the use of kinesis in combination with a display of gradual centripetal diffusion. The disc does not actually dissolve; rather, it mutates into a formless, shifting array of multiple individual parts, which resists the organising principles of the circular form. This evolving configuration can be seen to allude to a location beyond iconic, translatable, ‘complicit’ visual languages. This visual process is echoed by the rotating discs of isolated verbal signifiers. Kossentini heightens the verbal ambivalence present in Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma. Singular and plural nouns, with or without articles, coexist with adverbs and imperatives, as well as adjectives and past participles with feminine, masculine singular or plural agreements. These words and expressions, which are disconnected from a specific object and abstracted from syntactical order – and, moreover, from a single language – coalesce to generate an impression of an ambivalent and precarious Tunisia in transition. Associations can be made within and across discs between words connotative of freedom and constraint (an impression reinforced by the proliferation of imperatives), utopia and chaos, heaven and hell. This impressionistic use of the verbal – in parallel to the visual disintegration of the cohesive circular mosaic – articulates radical, intractable diversity, which cannot be contained by a system, be it linguistic, visual or political. The impression of intractability is compounded by the visual transculturation of artistic forms – the Islamic arabesque and the Duchampian Rotorelief – as well as the verbal insistence on ‘untranslatability’ in the transliteration of a number of Arabic words.

In Kossentini’s installation, Heaven or Hell, the same translatable visual symbol is exceeded not only through movement but also through additional, auditory and kinaesthetic, elements. In this alternative version of Le Printemps arabe (2011) the video of a fragmenting arabesque is projected onto the gallery floor. The discs displaying Arabic words are absent; instead, the same words are sung in German as part of an experimental soundtrack (the piece was first exhibited as Himmel oder Hölle at the IFA-Galerie in Berlin and Stuttgart, 2012). The disconnected words are accompanied by sounds that could be identified with shattering glass, multiple tumbling objects and a slowly creaking door. These contingent sounds exist beyond a musical order; that is, like the disconnected words, in the infra-thin passage between signifier and signified. In relation to the creaking door, it is tempting to recall Duchamp’s photograph of his door at 11, rue Larrey (1927), between closed and open, an ironic engagement with the French proverb, ‘Il faut qu’une porte soit ouverte ou fermée’ (‘A door must be open or closed’). In Kossentini’s work these untranslatable material processes are employed specifically to evoke an ambivalent, transitional Tunisia, between past and future, and a revolution that is ongoing.

The uninterrupted shots of the apparently arbitrary pattern of rotating and dispersing coloured fragments evoke a kaleidoscope – an impression that is enhanced by the sounds of loose, tumbling objects and shards of glass. It is suggestive of the multiple reflections produced by inward-facing mirrors – not only in a kaleidoscope but also in Duchamp’s use of a hinged mirror to produce a photograph portraying him simultaneously from five different vantage points (Portrait multiple de Marcel Duchamp, unidentified photographer, 1917).Footnote 13 Moving beyond the idea of multifaceted personal identity that is present in Duchamp’s portrait, Kossentini’s emphasis on multiplicity – and competing perspectives – signals post-revolutionary uncertainty since the (re-)emergence of diverse political voices. In this installation the shattering glass – together with the disconcerting, off-key song between music and recitation – heightens the sense of fragility. But visual, verbal and auditory multiplicity in Kossentini’s work equally evokes radical, intractable diversity. Duchamp’s five-way portrait suggests, as Craig Adcock writes, ‘the complexity, the multi-directionality, and outward expansion of the four-dimensional continuum away from normal space’ (Adcock, Reference Adcock1987: 155). Kossentini’s expanding pattern can similarly be seen to indicate metaphorically such an alternative space, while this is mobilised specifically to make way for an interpretation of the revolution in terms other than the binaries of success and failure. The words evocative of heaven and hell, in the soundtrack, could appear to interrogate the revolution in binary terms; moreover, the presentation of the literal revolutions of a disc could seem ironically to question whether the revolution is a reality or merely an illusion.Footnote 14 Yet, the visual diffusion of the arabesque points to the irrevocable rupture with dictatorship. Le Printemps arabe communicates ambivalence and tension; but the sensorial and dimensional shifts beyond symbols and systems in this work appear to allow for the idea that instability and fragility are inherent in the necessarily gradual process of democratic transition. The visualisation of an explosion and shattering resonates as much with Ben Jelloun’s characterisation of the onset of revolution as with Dakhlia’s emphasis on the resultant process of nascent democracy in the proper sense of the term:

Le piège de la dictature est brisé. Quand bien même elle entrerait dans la tourmente, la société tunisienne, comme d’autres sociétés arabes, serait sortie du schème mortifère d’une histoire étale et subie, d’une stabilité illusoire et imposée. Le rapport démocratique au politique est quant à lui par nature instable, toujours réversible et fragile.

(The fetters of dictatorship have been broken. Even while it might experience a period of upheaval, Tunisian society, like other Arab societies, will be free of the fatal monolithic representation of a history of weakness and subjugation, of a stability that is illusory and imposed. The relationship between democracy and the political is, by its very nature, unstable, always reversible and fragile.)

A further contingent, kinaesthetic element is introduced into this work via the spectator’s physical movement through the light projection, which disrupts, and further fragments, the kaleidoscopic arabesque. We might recall, here, Duchamp’s interest in ‘toutes les sources de lumière’ (‘all the sources of light’) and in the shadows they produce; as he states, ‘les porteurs d’ombres travaillent dans l’infra mince’ (‘the carriers of shadows work in the infra-thin’) (Footnote note 3, Footnote 21). The spectator’s physical interaction with the work doubles the conceptual exchange between the art object and the spectator, a further instance of the infra-thin.Footnote 15 In Kossentini’s work the spectator can be seen to embody this notion as they simultaneously create shadows and provide the shifting backdrop for equally mobile fragments of the evolving pattern. In this work, multidirectional shifts between dimensional and sensorial elements combine to generate a multisensorial experience of opacity for the diverse spectators. The reciprocity between ungraspable identities that is central to Glissant’s postcolonial concept is just as fundamental to Duchamp’s infra-thin. In its juxtaposition of both translatable and untranslatable elements, Heaven or Hell encourages the spectators to rethink their perceptions of the Arab Uprisings, while highlighting their inevitable involvement in their histories and representations.

Kossentini’s work resonates with the notion of the infra-thin – and Duchampian practices of the infra-thin – but, through the dynamic that it generates between stability and instability, it critiques, and holds in tension, different cultures and views of ‘difference’. It conveys a sense of ‘Western’ and ‘Arab’ cultures as interconnected and porous, yet specific, while it equally evokes alternative, singular perspectives. A strikingly comparable critical adaptation of Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs to communicate cultural interaction in ways that avoid, on the one hand, neo-colonial exoticism or abjection and, on the other hand, hybridisation can be found in the work of Mounir Fatmi. Fatmi (who works between Tangiers and Paris) reappropriates and adapts the Rotoreliefs specifically to critique alternative forms of global hegemony. His discs displaying Islamic calligraphic hadiths (sayings ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad) are accompanied by the jarring sounds of machinery to signal an equivalence between extremist uses of religion and the rapid technological developments characteristic of late capitalism, as well as exclusive canonical histories of art (Fatmi’s discs allude ironically not only to Duchamp but also to celebrations of modernity in paintings by Fernand Léger or Robert and Sonia Delaunay). This process appears to desacralise ‘Islamic’ objects, while it reorientates them to inhibit reductive perceptions of ‘Islam’. As in Kossentini’s work, the infra-thin passage between dimensions, which is rendered visible through kinesis, is allied to a multidirectional critique. Translatable visual languages are similarly held in tension, allowing for singular, untranslatable voices and nuanced perspectives. In Fatmi’s work ‘globalisation’ emerges as a multidirectional process, rather than a one-way phenomenon originating in ‘the West’. In video installations such as Technologia (2010, 15′) the spinning hadiths gather such a speed as to suggest the potential assimilation or annihilation of one culture by the other or, alternatively, their eventual fusion in a harmonious, universal, utopian space.Footnote 16 Yet, while the distinctive, translatable visual languages threaten to dissolve into a haze of whiteness, the sense of tension and irresolution between coexistent entities is maintained. Alternative cultures – symbolised by the hadiths and Rotoreliefs – remain recognisable and identifiable.

Fatmi’s video installation Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine – la chute (2012) engages with diverse states of revolution in North Africa and the Middle East. This work transposes and develops the artist’s earlier video installation Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine (2009–10; see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgXHL91MaQg).Footnote 17 Named after Chaplin’s ludic examination of the connection between industrialisation and alienation in Modern Times (1936), the earlier version of this work explores contemporary global forces of domination and alienation with particular reference to the rapid pace of urbanisation in the Middle East. The video – in this work and the later version – consists of a complex panoramic cluster of multiple circular hadith–machine cogs of different sizes, rotating clockwise or anticlockwise. These are combined with linear blocks reminiscent of skyscrapers within which ancient Kufik script shifts up and down, or right and left. Characteristically, manifestations of global hegemony – embodied by architecture and technology – are ambivalently aligned with religion through divine calligraphy.

Fatmi’s installation foregrounds the dangerous power of ‘machines’ or systems, including that of language – a connection which emerges emphatically through the inclusion, on the far right-hand side, of a number of Arabic letters with a key, in Latin script, to their pronunciation. This key can be seen to allude to the translatability of systems of power across cultures and, moreover, the complicity of Middle Eastern centres with global forces of urbanisation and economic liberalisation. Yet, the alternative ‘languages’ – still identifiable – are ambiguously contested through their juxtaposition and their setting in motion. Dimensional and cultural dissonance is exacerbated by the affective scraping and, at times, high-pitched sounds of machinery. These sounds can, from one perspective, be equated with the overwhelming, assimilating power of the global machine. But, in their irregularity and their frenzy, they appear to point to the instability and the unsustainability of mutually reinforcing systems. Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine was, indeed, created in the context of the worldwide recession which, by the end of 2009, had reached Dubai. Fatmi’s work resonates particularly with the situation of this Emirate which had managed, particularly through the lavish construction projects of companies such as Dubai World, to sustain an image of imperviousness to the credit crunch. In November 2009, though, this company announced that it would seek a six-month moratorium on repayments of its debt of £36.5 billion, sending shockwaves through the world markets (Teather, Reference Modern2009). Viewed against this backdrop, Fatmi’s work conveys resistance to ‘mirages’ of wealth and power. It also creates an impression of the fragility of ‘East–West’ relations in the context of a world on the brink of economic collapse.

Fatmi’s more recent version of this video installation combines references to the economic downfall – of the Middle East and the wider world – with allusions to the fall of dictatorships in the wake of the Arab Uprisings. This multi-layered ‘fall’ is signalled in the extension of the title: Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine – la chute, and emerges emphatically and dramatically in the video: the same intricate panoramic arrangement eventually fragments when the multiple objects are dislodged and literally fall away to leave a black screen. This work can be seen to allude not only to the complicity of ‘East’ and ‘West’ in the perpetuation of extravagant, yet debt-fuelled, construction projects but also to the diplomatic support given by many Western governments to former dictatorial regimes (see, for example, Lofti Ben Rejeb, 2013). Reminiscent of Kossentini’s installations, Fatmi’s work engages with, and contests, such political (and economic) complicity through the creation and dispersal of a transcultural symbol or linguistic system of symbols. Through such a process, it similarly alludes to the ‘fall’ of social and cultural stability – which was founded on a myth of political cohesiveness – ambivalently raising the question as to whether those revolutions that have taken place have succeeded or failed. Exhibited in 2012, it could be seen to ask whether the uprisings that continue, in countries such as Syria, are worth the tragic loss of life they have engendered. Yet, the work resists a firm political statement, functioning rather to raise questions for further debate and to highlight what critics such as Fahed Al-Sumait et al. (Reference Al-Sumait, Lenze and Hudson2014b) have shown to be the complexity and uncertainty of diverse states of ongoing revolution. As in Kossentini’s work, the process of deconstruction and destruction evokes irrevocable rupture, a necessary tabula rasa, and the inevitable turmoil of emergent (and potential) democracies.

Kossentini’s and Fatmi’s works demonstrate how a multidirectional, infra-thin critique can be evoked through dimensional and sensorial shifts, and particularly through the use of kinesis. They evoke both fragility and resistance to diverse essentialising views of the revolutions in a transnational context and simultaneously, in Kossentini’s installations, in post-2010 Tunisia. The tension between stability and instability, the translatable and the untranslatable, that is central to such a critique can alternatively be evoked by exploring the dialectic between presence and absence.

‘Poetics of Absence’: Commemoration and Resistance from Tunisia to Syria

This ‘poetics of absence’ (to employ the expression used by artist Safaa Erruas) takes a number of forms, from the use of light and shadow or reflection to the practices of weaving in white or etching on glass (Erruas, Reference Erruas2012: 80). While the works of Kossentini and Fatmi allude to local and regional practices of ceramic production and calligraphy, the methods and materials employed by Erruas, Kallel, Filali and Safadi are reminiscent of a range of existing transnational or local practices. Their works resonate with the notion of the infra-thin in their suggestion of passage, nuance, instability and contingency, while they innovatively adapt and combine existing practices or develop alternative means of rendering visible the invisible. At the same time, reminiscent of Kossentini’s and Fatmi’s ‘revolutionary arabesques’, their poetics of absence comes to be associated with both fragility and resistance as they respond to regional and/or local instances of revolution.

Installations by Safaa Erruas (based in Tetouan, Morocco) and Tunis-based Sonia Kallel explore revolutionary tensions through contrasting uses of colourless organic material. Erruas’s Les Drapeaux (2011–12) consists of the flags of the twenty-two member states of the Arab League, which are remade through the painstaking process of embroidering tiny white pearls onto white cotton paper (Figure 1.1).Footnote 18 While the use of white on white was not a practice employed by Duchamp, the attenuated flags resonate with his note regarding colours: ‘Transparence “atténuant” les couleurs en infra mince’ (‘Transparency “attenuating” the colours in infra-thin’) (Footnote note 24, Footnote 26). This practice resonates more immediately with Russian artist Kasimir Malevich’s White on White (1918), a tilted square within a square in different tones of white. Through this non-objective Suprematist painting, produced one year after the October Revolution, Malevich sought a language that would distance art from the visible world – and from service to the state or religion – cohering with his anti-materialist, anti-utilitarian philosophy (‘Suprematism’ is the name Malevich gave to his abstract art characterised by basic geometric forms painted in a limited range of colours, from 1913; see Tate.org, n.d. a). In Erruas’s work, by contrast, this practice is ironically adapted to depict objective, political symbols.Footnote 19 Les Drapeaux retains clear links to the visible world, while it avoids both the iconic language of revolution and the opposite extreme of abstraction. It forges an ‘infra-thin’ language between visibility and invisibility. Grouping together the multiple flags, this work signals diversity within the MENA region. It draws attention to the contrasting situations of the nations that are frequently encapsulated in the international media by expressions such as ‘Arab Spring’. Draining these symbols of colour, however, the installation simultaneously questions the idea of national, or regional, cohesion. These delicate objects communicate the current fragility of diverse Arab countries.

Erruas’s delicate colourless handmade flags are reminiscent of Brazil-based artist Mira Schendel’s drawings on rice paper combined with clear acrylic, through which she pursued the idea of ‘transparency’.Footnote 20 Erruas’s suspension of multiple flat rectangular objects, which can be seen from both sides, is particularly comparable to Schendel’s installation Variantes (1977).Footnote 21 A connection can also be made to a further rare installation by Schendel, which visualised invisibility as a silent means of resisting the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964–85): Ondas Paradas de Probabilidade (Still Waves of Probability) (1969) consisted of thin nylon threads hanging from the ceiling and gathering on the floor.Footnote 22 But Erruas, who creates all her work in white, uses the method of embroidery. She forges a visual language which resonates as much with transnational modernist aesthetics as with a method traditionally practised by communities of women in the Maghreb. Her white-on-white practice reminiscent of Malevich’s geometric abstraction is combined with this delicate ‘feminine’ practice. Yet, it is through this ‘feminine’ practice that she resists essentialising views.Footnote 23 The absence articulated by this work can be seen to create a space specifically for women’s voices. It draws attention to the particularly fragile and uncertain situation for women in apparently post-revolutionary contexts such as that of Tunisia. The work was produced in the same year as the controversy in Tunisia provoked by the draft constitution (released in August 2012) in which women’s role would be ‘complementary’ rather than ‘equal’ to that of men (see, for example, Allani, Reference Allani2013; Charrad and Zarrugh, Reference Charrad and Zarrugh2014; Labidi, Reference Labidi, Al-Sumait, Lenze and Hudson2014b). Les Drapeaux diverges from other pieces by this artist, which evoke violence against the female body. It can be seen, rather, as a quietly subversive expression of female subjectivity and regional solidarity. For Erruas, her ‘poetics of absence’ is also a form of mourning (Erruas, Reference Erruas2012). In its fragility this work poses questions as to futures of nations in North Africa and the Middle East, while it simultaneously mourns the deaths of martyrs for the cause of the revolutions, and perhaps the oppression of certain communities in their aftermath. The laborious process of embroidery comes to be associated with catharsis. Reminiscent of Kossentini’s work, in Les Drapeaux the infra-thin passage between colour and transparency, the objective and the non-objective – and, moreover, artistic practices constructed as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ – can be seen to convey fragility but also to evoke a multidirectional critique. It is this dynamic that encourages an ‘other’ mode of thinking and viewing in Khatibi’s sense. This work resonates with infra-thin tensions between opposites, while it develops a distinct and diversely transnational poetics of absence and resistance to alternative essentialising forces: neo-colonialism, dictatorship, (internal and external) patriarchal views of women, and the art historical canon.

The dynamic, in Erruas’s work, between presence and absence, death and life, fragility and resistance, past and future, finds a parallel in Sonia Kallel’s sculptural work Which Dress for Tomorrow? (2011; Figure 1.2). Kallel’s minimal work, by contrast, evokes an absent body through the use of beige jute fibre, analogous – both in its colour and in its organic, porous qualities – to human skin. Kallel has employed this material in previous works, such as Ma Robe de mariage (My Wedding Dress) (2003), which resembles both a constrictive dress and the distorted skin ‘cast’ of a human body. Suspended on a wire hanger chained to the ceiling, this dress evokes a haunting apparition. In Which Dress for Tomorrow? The same ‘cast’ is compressed into a tight ball which is held together by taut metal wires and suspended by a transparent thread.Footnote 24

Through ambivalent sculptural ‘casts’ between presence and absence, Kallel’s sculptures communicate simultaneously both incarceration and liberation:

My coverings are an expression of experiences and conflict situations. In my works I allow body and clothing to encounter each other in a relationship of power. The desire to attach the body and subject it to extreme aggression was triggered by an immense, almost compulsive drive within me. My approach is based on compulsion and characterized by a kind of sadism towards the body: I pull my inadequate items of clothing over it, causing unpleasant, painful sensations. To an equal degree, these coverings are skins that I remove to release the body; they oscillate between dream and reality. They are independent subjects, porous surfaces that breathe and live. And they are complex skins that disclose an injury to the body and project anyone attempting to resist them into an oppressive universe. These coverings call to mind unpleasant situations and express a feeling of being imprisoned, a shortness of breath and fear. They tell of pain and suffering …

Kallel’s works convey a similar dynamic to that which is present in Erruas’s work. But Kallel focuses on the antagonistic relationship between body and clothing. Her visceral practice, which exploits the contrasting qualities of jute, conveys sensorial – as well as conceptual and emotional – ambiguities, which affect and interpolate the spectator.

Ma Robe de mariage can be seen to use this ambivalent material to signal the separation and dynamic between the constructed identities imposed on women and their ‘real’ status as living, breathing, embodied subjects. While this work seems to point to the pain and suffering that can arise from this discrepancy for women in diverse ways across the world, it is related specifically to Tunisia, cohering with the aims of the exhibition in which it was presented: ‘La Part du corps’ (Palais Kheireddine, Tunis, 2010).Footnote 26 Sonia Kallel has said that the idea was to express the tension between the female body and ‘une société conservatrice, oppressive et étouffante dans laquelle on vit. Une pulsion immense, presque compulsive en moi m’a poussé à traduire ce sentiment d’oppression dans cette peau-vêtement’ (‘a conservative, oppressive and suffocating society we live in. I was driven by an immense, almost compulsive, urge to translate this feeling of oppression into this skin-dress’).Footnote 27 As the curator of this exhibition, Rachida Triki, stated: ‘In an Arabo-Islamic country, it is important that artists remind [us] and highlight the importance of the body in the private, social, and cultural life’ (Triki, in interview with Binder and Haupt, Reference Binder and Haupt2010). Kallel’s skin-dress offers, though, a nuanced exploration of oppression: ‘elle reflète cette identité opprimée où le port du voile n’est qu’un “chapitre” d’oppression parmi d’autres’ (‘it reflects this oppressed identity in which the wearing of the veil is merely one “chapter” of oppression among others’).Footnote 28 Kallel’s dress-sculpture can perhaps also be seen to counter the visions of women’s complete liberation perpetuated by Ben Ali’s regime and supported by Western governments at that time. Created eight years in advance of the revolution, this work materialises an infra-thin ‘skin’, contesting alternative iconic visions; it reveals enduring aesthetics of resistance. It anticipates the increasing complexity of such critiques in a post-revolutionary context in which women continue to be employed, from different perspectives, as symbols of national identity.

Kallel’s Which Dress for Tomorrow? transposes her specific use of jute fabric to a ‘post-revolutionary’ context to explore uncertainties regarding Tunisian identity and the country’s future, while the reuse of the material for Ma Robe de mariage suggests that oppression continues, despite the revolution. As Kallel has stated, ‘[c]ette même enveloppe, avec la révolution, s’est transformée, elle s’est enfermée sur elle-même en une sorte de boule’ (‘this same envelope, with the revolution, transformed itself; it closed in on itself in a kind of ball’).Footnote 29 The bundle of material, comparable to a tightly compressed yet living and breathing body, appears constricted by the metal wires that suspend it. The jute, though, necessarily bulges and sags beyond the rigid wires. The irregular mass of natural, porous material evokes inevitable, organic growth despite any attempts to restrain it. On one level, this sculpture can be understood to express the uncertainties facing women in the light of rising extremist forms of Islamism. The question regarding ‘dress’ can be interpreted literally to allude to the concerns of some Tunisians regarding the future of sartorial liberalism. This interpretation is encouraged when the sculpture is placed in close proximity to Mouna Jemal Siala’s video, Le Sort (The Fate; 2011–12), as it was at ‘Rosige Zukunft’ (Rosy Futures) (Stuttgart, 2013). Jemal Siala’s three-minute piece displays a shifting portrait of the artist, whose face is progressively ‘veiled’ using black paint as we hear Erik Satie’s ‘Lent et douloureux’’(Slow and Painful) (Paris, 1888) (see Chapter 4). While Kallel’s work engages only implicitly with debates surrounding the practice of veiling in Tunisia, via its title, both works use ‘dress’ to raise the wider question of national identity. Like Erruas’s installation, Kallel’s Which Dress for Tomorrow? evokes the revolution’s impact on women and on wider society (indeed, the idea of oppression conjured by her earlier ‘skin-dress’ already exceeded the question of veiling, as indicated above). The title, looking towards the future, can be understood to be asking: what will Tunisia ‘look like’? Where is the country heading? Can a way be found to allow diverse perspectives to coexist? The compressed, yet still ‘living’, organism evokes those voices of democracy that were suppressed during decades of dictatorship and that – even despite the events of January 2011 – have yet to be heard; that is, a neglected social body. Kallel’s sculpture expresses ambivalence with regard to the revolution, one year on, conveying the continuing suppression of diverse voices while simultaneously indicating the possibility for change.

In exploring the liminal boundaries of the body, rather than the body itself, Kallel’s works are, to an extent, reminiscent of Duchamp’s use of moulds and casts, as in his Female Fig Leaf (1950; bronze). But Kallel’s works use flexible, organic materials. For Which Dress for Tomorrow? she selects a material which has been produced for centuries in regions from Bengal to the Middle East. Jute was not employed by Duchamp, though this organic material provides a fitting tool for the liminal processes he favoured. In its porosity, jute lends itself particularly well to materialising an ambivalent infra-thin separation, while simultaneously evoking the alternative domains of the body and the world within which it moves. Duchamp mentions the characteristic of ‘porosité’ (‘porosity’), along with ‘imbibage’ (‘imbibing’), in his discussion of infra-thin, frequently organic, substances (note 26v, 27). Kallel’s reuse of jute to allude ambivalently to clothing and human skin resonates, moreover, with the infra-thin semantic shifts between signifier and signified, materiality and metaphor. Kallel’s use of jute is, though, more reminiscent of Joseph Beuys’s predilection for organic materials. The Fluxus artist exploited the contrasting sensations and emotional connotations of materials such as felt (which mixes both organic and industrial fibres). Felt – which, like jute, ‘imbibes’ anything with which it comes into contact – can be stifling and claustrophobic but also warm and protective. Kallel’s signature material is similarly mobilised to allude to contrasting associations: jute is rigid yet porous, oppressive yet breathable, imprisoning yet (potentially) liberating. Which Dress for Tomorrow? plays also on the contrast between organic jute and industrial metallic wiring. The combination of industrial and organic, rigid and pliable, materials is particularly reminiscent of Eva Hesse’s sculpture in which soft, ‘feminine’ materials evocative of human forms could be seen to subvert the geometries of male-dominated American minimalism.Footnote 30 Kallel’s ‘ball’ of material suspended by taut threads is strikingly reminiscent of Hesse’s Vertiginous Detour, in which a ball, hanging from the ceiling by rope, is enclosed in netting, an experiment with tension and gravity which can similarly be seen to communicate provisionally inhibited freedom (1966; acrylic and polyurethane on rope, net, and papier-mâché). This work is engaged with more explicitly in Kallel’s Sens unique (One Way), a large sculptural ball of hair and fabrics, which is suspended using a fishing net (2012; 450 × 150 × 150 cm).Footnote 31 But this alternative anthropomorphic sphere adapts Hesse’s ambivalent practice to evoke the restrictions and tensions of post-revolutionary Tunisia, as well as the uncertainties with regard to the country’s future: the title of this work perhaps suggests a more pessimistic outcome than the more ambivalent contemporaneous Which Dress for Tomorrow?.

Kallel’s works tie these dynamics to the ambivalence of the Tunisian revolution between oppression and liberation. In the context of art exploring this revolution, the affective ambiguity between malleable, organic material and taut metallic thread in Which Dress for Tomorrow? is reminiscent of Meriem Bouderbala’s mixed media series, The Awakened I–IV (2010). Bouderbala evokes the bodies of martyrs of the revolution in fluid, contingent ink and wash, while they are bound and suspended by taut blood-red thread attached to sharp needles. The use of the same needles to emblazon the figures with symbols of Christianity, Islam and Judaism ties the visual-haptic ‘clash’ to religious conflict, while perhaps posing the same question as Kallel’s sculpture with regard to the possible coexistence of diverse ways of being Tunisian. Kallel’s evocation of potential liberation despite constraint through the ‘skin’ of an absent body finds a parallel in Mouna Karray’s photographic portraits displaying her ambivalently confined and shrouded yet dynamic present body. Karray’s series also resonates with Erruas’s exploration of revolutionary dynamics through white on white (Noir (2013); see Chapter 4).Footnote 32

While Erruas’s Les Drapeaux incorporates flags and reworks these icons directly, Which Dress for Tomorrow? explores an allusive alternative to the potentially iconic body and dress. Kallel’s evocation of constraint and violence contrasts with Erruas’s investigation of fragility and a process of mourning. Erruas’s work is primarily one of commemoration in relation to diverse forms of revolution in North Africa and the Middle East; that of Kallel addresses the uncertain future of Tunisia. Yet, these works converge in resonating with infra-thin dynamics while developing alternative ‘languages’ in which it is possible to evoke the idea of revolution between the binaries of success and failure, black and white, and beyond the bright colours and bold outlines of photographic icons.

Comparable ‘revolutionary’ poetics of absence can be found in art that uses glass or clear plastic screens by Aïcha Filali and Shada Safadi, though these artists develop distinctive aesthetics involving the photographic image or the use of light and shadow and depending on the spectators’ movement. Aïcha Filali’s work, like that of Kallel, engages specifically with Tunisia, which saw the fall of Ben Ali’s dictatorial regime on 14 January 2011, but which continues to experience the turbulence that is inherent in the process of democracy. Shada Safadi’s work, by contrast with the works I have analysed in this chapter until now, mourns and commemorates those lost in the violent ongoing revolutionary conflict in Syria. On one level, this poignant work can be taken to speak universally of the tragic loss of civilians in war, but it is most evocative of the civil war in Syria.

By contrast with the uprising in Tunisia, which led to the removal of an autocrat and to democratic elections within a year, the uprising in Syria was rapidly repressed by the state. What began as a peaceful revolt on 15 March 2011 developed, in 2012, into an intractable civil war between Assad’s government and the oppositional Free Syrian Army, which is still ongoing at the time of writing. While the revolutionary uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt triggered the initial Syrian uprising, this has unfolded in distinct and more complicated circumstances. As Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel have stated, ‘[w]hile the conflict in Syria has its origins in domestic politics – rooted in the corruption, nepotism, cronyism and repression of 42 years of Assad family rule – its regional and international dimensions are manifold’ (Hashemi and Postel, Reference Hashemi, Postel, Hashemi and Postel2013a: 6). Indeed, the conflict has led to new geopolitical rivalries and global divisions between the multiple countries which have a stake in its outcome, paralysing the UN Security Council (Hashemi and Postel, Reference Hashemi, Postel, Hashemi and Postel2013a: 6–7; see also Safadi and Neaime, Reference Safadi, Neaime, Elbadawi and Madkisi2016). The war has become even more complex and intractable given the rise of radical Salafi jihadi movements (Hashemi and Postel, Reference Hashemi, Postel, Hashemi and Postel2013a: 8). The year 2012 in which Safadi created her work – saw the escalation of violence in Syria, the failure of the UN ceasefire attempt, and the declaration of the conflict as a civil war, on 15 July, by the International Committee of the Red Cross. A report of 14 April 2018 by Al Jazeera stated that more than 465,000 Syrians had been killed in the fighting, over a million had been injured and over 12 million – half of the country’s pre-war population – had been displaced.Footnote 33 Safadi’s poignant installation responds to the already extensive human cost of the war one year into the conflict.

The distinct contexts and states of ‘revolution’ evoked by these works set them far apart in terms of both their content and their tone. Yet, they mobilise a comparable aesthetic similarly to create a space in which civilians can be represented in non-iconic ways, and to encourage alternative modes of interaction. The work of these artists resonates (unintentionally) with Duchamp’s perception of glass and mirrors as infra-thin planes between two- and three-dimensionality and his preoccupation with their capacity to reflect, to reverse and to allow for the contingent. This is most famously exemplified by his work in glass: La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, even) (1915–23), also known as Le Grand verre (The Large Glass), in which he employs a complex iconography to explore male–female relations (see Marcel Duchamp, Reference Duchamp, Schwartz, Hamilton, Gray and Schwarz1969).Footnote 34 At the same time, these works of 2012 call to mind enduring local practices of painting under glass or engraving glass. Both, though, develop alternatives to existing local and transnational practices to exceed iconic representations of radically different experiences and stages of ongoing ‘revolution’.

Photography and video are perhaps the most challenging media in which to present an alternative language of revolution, given that it is in these media that icons of the ‘Arab Spring’ have tended to be constructed and disseminated. These icons have frequently focused on heroic bodies, such as ‘The Girl in a Blue Bra’ who was killed during demonstrations in Tahrir Square, or ‘spectacular body acts’ from self-immolation to nude activism, as Marwan Kraidy has shown (Kraidy, Reference Kraidy2016). Aïcha Filali, however, uses photography to depict ordinary people and to create a space for alternative non-heroic and non-spectacular visions. This Tunis-based artist’s series, L’Angle mort (Blind Spot, 2010–12), captures oblique back views of ordinary Tunisian people in the street and presents life-size cut-outs of them on windows or clear plastic screens (Figure 1.3). At ‘Rosy Futures’ at the IFA Gallery Stuttgart, for example, the figures were presented on the gallery windows, facing outwards towards the street.Footnote 35 The photographs reveal details which are usually hidden from view or simply go unnoticed: a crumpled or untucked shirt, for example, or the creases of trousers gathering around the buttocks. This project was begun in advance of the revolution and developed in relation to this new context. L’Angle mort was first presented on clear plastic screens at the Galerie Ammar Farhat, Sidi Bou Said, Tunisia, in 2010. Elitism – including that in the art world, in and beyond Tunisia – is a recurrent theme in Filali’s work. As Mohamed Ben Soltane states of the 2010 series (examples of which he presents in his post-revolutionary virtual exhibition, ‘Souffle de Liberté / Tunisie’ (2011)): ‘Ces gens qui ne font pas partie du public habituellement “très select” des galeries d’art, s’approprient un espace duquel ils sont socialement exclus. Quelques mois plus tard, en Janvier 2011 et cette fois dans la réalité, ils s’approprieront l’espace politique en étant dans la première ligne de ceux qui chassèrent le président déchu du pays’ (‘These people who are not usually part of the normally “very select” public of art galleries, appropriate a space from which they are socially excluded. A few months later, in January 2011, and this time in reality, they will appropriate the political space by being on the front line of those who drove the deposed president out of the country’) (Ben Soltane, Reference Ben Soltane2011). This exhibition was greatly appreciated in Tunisia (see, for example, Abassi, Reference Abassi2010).Footnote 36 Filali – like Kallel – can be seen as one of the ‘non-collective actors’, and her pre-2011 oeuvre as one of the many ‘dispersed endeavors’, which Gana perceives to have contributed to the Tunisian revolution itself (Gana, Reference Gana and Gana2013: 2).Footnote 37

At the ‘Rosy Futures’ exhibition, which occurred after the Tunisian revolution, L’Angle mort includes a photograph of a man flying the Tunisian flag above two further cut-outs of people in the street. In this image, as in the other photographs, we cannot see the man’s face or the focus of his gaze; the scene itself is missing. The cut-outs below the man, in which there is no link to the protests, similarly show the backs of a couple looking downwards together at an item we cannot see and a man making a positive thumb-up gesture to someone who is obscured from our view.Footnote 38 Here, we are invited to look ‘behind’ the iconic media images of the revolution. Revolutionary demonstrations, moreover, are allied with the ordinary through their juxtaposition with unknown people engaged in everyday activities. Filali’s spontaneous photographs of unknown people can also be seen as counterpoints to the pre-revolutionary pervasiveness of iconic images of Ben Ali. Her work is reminiscent, in this way, of the Paris-based ‘JR’’s collaborative street art project, InsideOut (Tunis 2011), which involved pasting portraits of ordinary people at sites previously occupied by the former leader’s photograph (see Chapter 4). But Filali more subtly explores the boundary between inside and outside by combining photography with glass.

Interpreted through the lens of the ‘infra-thin’, Filali’s use of glass to support her cut-outs renders visible an infra-thin screen. Viewed from inside, the silhouettes of the people she photographs can be compared, to some extent, to the figures in Duchamp’s Le Grand verre, which he imagined as shadows of a quasi-fourth-dimensional space. They also resonate with his note: ‘Peinture sur verre vue du côté non peint donne un infra mince’ (‘Painting on glass seen from the non-painted side gives an infra-thin’) (Footnote note 15, Footnote 24). But the practice of presenting images behind glass is also reminiscent of the ancient Tunisian tradition of painting under glass.Footnote 39 This enduring tradition was influenced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as Hocine Tlili details, by Italian and Turkish figurative representation (Reference Tlili, Barsch, Bruckbauer and Baatsch2012: 163). Filali’s practice diverges from both aesthetics in presenting back-views of ordinary passers-by. Her work produces an alternative form of reversal and a different means of incorporating contingency; that is, through the spontaneous use of the instantaneous medium of photography. By contrast with the two-dimensional figures of Tunisian painting and, even more so, with the upturned mechanomorphic figures of Duchamp’s Large Glass, Filali’s photographs appear as indices of three-dimensional corporeal reality. L’Angle mort invents new means of visualising invisibility, which resonates with the political aim to include those who are not usually deemed worthy of representation.

As the artist states, ‘je voulais donner à voir les différents caractères de la typologie des Tunisiens mais vus de dos. L’intérêt de ce support transparent et grandeur nature c’est de créer une confusion entre les spectateurs et les personnes qui sont représentées sur le verre’ (I wanted to bring into view the various characteristics of Tunisian types but seen from behind. The point of using this transparent and life-size format is to create an intermingling of the spectators and the people who are represented on the glass’).Footnote 40 The people represented occupy the threshold between inside and outside, art and life. Mingling with shifting reflections of the city, they seem to walk within it. The images evolve with the changing light and with the equally contingent perspectives – and reflections – of the mobile spectator, producing, we might say, an alternative experience of ‘fourth-dimensional’ outward, multidirectional expansion to that visualised by Kossentini’s kaleidoscopic arabesque. Duchamp conceived of the infra-thin as a liminal separation either in space or in time: ‘séparation inframince – mieux que cloison, parce que indique intervalle (pris dans un sens) et cloison (pris dans un autre sens)’ (infra-thin separation – better than partition, because indicates interval (understood in one sense) and partition (understood in another sense)’) (note 9r, 22, emphasis Duchamp’s). But this work materialises a separation characteristic of the infra-thin to create a space for those who have tended to be excluded from iconic visions of Tunisia and to encourage contemplation of the historical interval between the revolution and the present moment of the exhibition. The spectator and the wider hors champ are, moreover, incorporated in a way that indicates the porosity of, and exchange across, cultural borders.Footnote 41 In Filali’s work, photography comes to be aligned with uncertainty and contingency, a point that is developed further in Chapter 2’s consideration of ‘contingent encounters’.

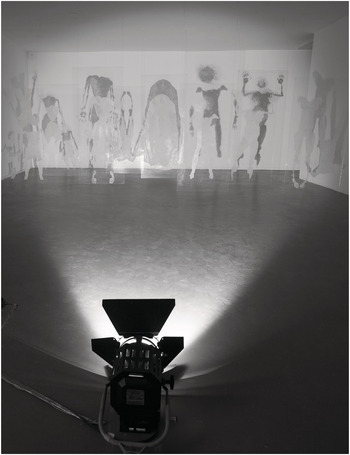

Evoking the distinct context of the war in Syria, a contrasting work, Promises (2012) by Shada Safadi (based in the Syrian Golan Heights), communicates the tragic loss of hundreds of thousands of civilians (Figure 1.4). In this haunting installation, multiple vertical transparent plastic screens poignantly display life-size images of human bodies – both adults and children.Footnote 42 The distorted white figures are etched by hand (their whiteness comes from the use of heat during the etching process), while they give the impression of imprints, as if the bodies had been laid on the clear surfaces.Footnote 43 Light is projected onto the screens, illuminating the translucent shapes and casting ghostly shadows on the surrounding walls. As the spectator disrupts the light ray and walks between the screens, their own shadows fuse with those of the dead. The artist’s statement accompanying the work expresses the guilt of those who have survived, the need to remember the dead, and the necessity to continue the battle for which these people lost their lives, until freedom from oppression is achieved:

That spirit could have flown without being seen by anyone. But the horror of what happened, and its struggling out of fear, made it leave an impact that demands of us, we the ones who are alive, to give promises. We ‘forget the promises we give to our dead,’ we keep them for some few days and then forget. We did not see things ourselves when they happened … We saw it after it happened, and the scene etched itself in our memory. How can we apologize for that spirit that took us out of darkness? You still exist and we were meant to stay alive, but our freedom is still incomplete; you are dead and we are the dead too.Footnote 44

Safadi’s work resonates formally with diverse infra-thin practices, while it develops an alternative means of rendering visible the invisible to share an experience of loss and mourning. The use of transparent screens to visualise the liminal traces of other-worldly figures is reminiscent of Duchamp’s practice in Le Grand verre. But in Safadi’s work the dimensional passage occupied by the figures – some upright, some upturned – is assimilated to the passage from life to death. The multiplication of figures, moreover, each occupying their own screen, evokes the mindless execution of anonymous masses. The shapes’ resemblance to contingent corporeal imprints resonates formally, to some extent, with Yves Klein’s multiple Anthropometries (1960), the results of performances in which he asked women to cover themselves in ‘International Klein Blue’ paint before pressing their bodies against white paper. For the New Realist artist, these imprints rendered visible the border between materiality and the void, corporeality and spirituality (see Morineau, Reference Morineau and Morineau2006). Such liminal zones and passages are, in Klein’s work, suggestive of the transcendence of the earthly, corresponding with this artist’s interest in Rosicrucianism. Safadi’s work resonates with avant-garde practices of rendering visible the invisible, in the work of both Duchamp and Klein. But her translucent figures evoke lifeless bodies with skeletal limbs. Although these distorted forms are suggestive of contingent corporeal imprints, furthermore, closer scrutiny reveals their gradual formation through intricate loops etched by hand. Rapid modes of image production, such as body printing, or the instantaneous medium of digital photography employed by Filali, are eschewed in favour of a painstaking process that is reminiscent of the long Syrian tradition of enamelling glass. Safadi’s practice echoes her words: ‘the scene etched itself in our memory’. This process can be seen to contribute to the cathartic enterprise of remembrance and of making and keeping, in the artist’s words, ‘the promises we give to our dead’.

Safadi’s Promises transforms mourning and remembrance into an active process which is extended to the spectator. As in Kossentini’s installation, light and shadow are employed to embody the participant. In this case, their shadows merge with those of the ghostly figures; their acquired status as mobile ‘porteurs d’ombres’ (‘carriers of shadows’), between embodiment and disembodiment, heightens their awareness that they ‘were meant to stay alive’ but others were not. Their kinaesthetic experience leads to their emotional understanding of the artist’s words: ‘you are dead and we are the dead too’. The spectator’s emotional comprehension of the work is equally encouraged through its treatment of the universal themes of death and remembrance and through the use of traces and shadows of absent bodies, rather than photographs of people in locatable environments such as we see in Filali’s photographs. In both its themes and its aesthetics, Safadi’s work is strikingly reminiscent of Christian Boltanski’s Théâtre d’ombres (1984), while Boltanski’s installation ambivalently provokes both sadness and laughter (see Grenier and Boltanski, Reference Grenier and Boltanski2007). In Théâtre d’ombres, small handmade metal figurines of skulls, ghosts and masks dangle near the gallery floor, with light spots close by to project multiple exaggerated shadows onto the gallery walls. In formal terms, the use of shadows in the work of both Safadi and Boltanski is reminiscent of ancient traditions of shadow theatre in multiple countries across the world. It also resonates with Duchamp’s use of these infra-thin phenomena to evoke a quasi-fourth-dimensional space: one of his notes on the infra-thin includes a photograph displaying shadows of his ready-made objects (Footnote note 13, Footnote 25). Such a space, moreover, is evoked in the works of both Safadi and Boltanski through the effect of multidirectional outward expansion generated by the use of low-angle lighting from a single source (or group of spotlights, in Théâtre d’ombres). In the work of both artists this alternative location is assimilated to the domain of the dead. Yet, Safadi’s work produces a markedly different tone from Boltanski’s ‘danse macabre’. The shadows of Promises are identified with the bodies of those lost during a historically specific war. Safadi’s work is closer, at least in content and tone, to other works by Boltanski which evoke the death of Holocaust victims while also exploring human suffering universally.Footnote 45

Reminiscent of Erruas’s work, Safadi’s poetics of absence constitutes a form of mourning. Safadi employs a distinctive use of white but does so similarly to evoke the liminal zone between life and death. She also develops a comparable painstaking, yet perhaps cathartic, process. Safadi’s work, by contrast, appears to focus exclusively on loss, functioning primarily as a testimony to the tragic results of revolutionary conflict. Yet, it can also be seen to gesture towards the future in its transgression of the boundaries between the disembodied and the embodied, and via its message that ‘our freedom is still incomplete’. Promises forges a means of evoking the dead, and the revolutionary cause for which they fought, which avoids the potentially iconic images produced by the media. Closer to media images, certain recent artwork exploring the Syrian war exposes the extreme violence inflicted on civilians, such as Tarek Tuma’s portrait painting of Hamza Bakkour, the thirteen-year-old boy shot in the face during a siege in Homs in February 2012.Footnote 46 Such artwork is reminiscent of photojournalism and filmed reportage in its function to shock the international public. Installations such as that of Safadi provide a necessary counterpoint to such iconic language, engaging the spectator intellectually, physically and emotionally in cross-cultural experiences of opacity, and calling for democracy – not only in Syria and the wider Middle East and North African region, but in diverse situations across the globe.

Comparable to Erruas’s Les Drapeaux and Kallel’s Which Dress for Tomorrow?, these works by Filali and Safadi resonate with infra-thin dynamics, and with a range of transnational and local practices, while ‘anchoring’ such dynamics. At the same time, through L’Angle mort and Promises, these artists develop alternative poetics of absence by combining photographed or painted anonymous figures with transparent screens. These spatially more extensive installations involve the spectators kinaesthetically and generate reflections or shadows, which heightens the experience of instability and contingency.

The ‘infra-thin critique’ in these works, and in the installations by Kossentini and Fatmi, can be situated in relation to wider aesthetics of resistance.Footnote 47 In rendering visible the invisible to avoid, and often explicitly contest, icons, clichés or other visual languages associated with order and authoritarianism, these works are reminiscent of certain art exploring (neo-)colonialism or globalisation. I have already discussed Fatmi’s earlier uses of the spinning arabesque as precedents for the dimensional shifts in his later work and in that of Kossentini. Critical ‘poetics of absence’ can be discerned in works that forge an alternative, non-reductive visual language with which to convey experiences of exile through immigration. Zineb Sedira captures shadows in light boxes to evoke such an experience for Algerian women (Exilées d’Algérie: Amel, Fatiha, Salia, Zoulikha and Aïcha, 2000), while Hamid Debarrah employs photographic positive and negative in his ‘double’ portraits of male immigrant workers (Faciès inventaire: chronique du foyer de la rue Très-Cloîtres à Grenoble (‘Face Inventory: Chronicle of the Hostel on the Rue Très-Cloîtres in Grenoble’) (2001). In a divergent way to Kallel, Saadeh George creates resin ‘casts’ resembling skin to explore the fragility of identity and the effects of displacement in Today I Shed My Skin: Dismembered and Remembered (1998; photography, photo etching and resin) (see Lloyd, ed., Reference Lloyd1999: 52). Exploring alienation in a globalised frame, Kader Attia’s numerous fragile aluminium moulds of veiled figures bowed in prayer seem to signal an equivalence in religion and consumerism as alternative forms of (empty) refuge (Ghost, 2007). Filali’s work is reminiscent of Samta Benyahia’s use of gallery windows as the support for her deep blue moucharabieh.Footnote 48 This Arabo-Andalusian architectural screen, which in North Africa was traditionally designed to separate gendered spaces while allowing the women to see through its openings, is transposed to emphasise the porosity of the boundaries between cultures on either side of the Mediterranean. Alternative aesthetics of revolution do not simply and suddenly emerge with the revolutions that began in 2011. Yet, these works develop new practices in response to this shift in context and to the iconic language of ‘revolution’. They explore conceptual and sensorial shifts, passages between dimensions or between presence and absence, or exchanges between spectator and object, specifically to evoke both past and future, to commemorate while looking forwards and to communicate uncertainty yet also possibility.

Infra-thin Critique and Transnational Criticism

Diverse works exploring the Arab Uprisings, or their distinct manifestations in Tunisia and Syria, resonate with infra-thin dynamics. They allude doubly – or multidirectionally – to apparently stable, separate identities or discourses, while rendering visible the space or interval between them. But, in these works, such dynamics are ‘anchored’ in relation to specific cultures and historical moments. Singularising infra-thin practices come to be associated with resistance to iconic visions in contexts of ongoing revolution or emerging democracy. They create a space for alternative voices, visions and understandings of distinct revolutionary situations. These works hover not only between the specific and the singular, and between metaphor and materiality, but also between the translatable and the untranslatable, politics and poetics, in their evocation of an infra-thin critique.