Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

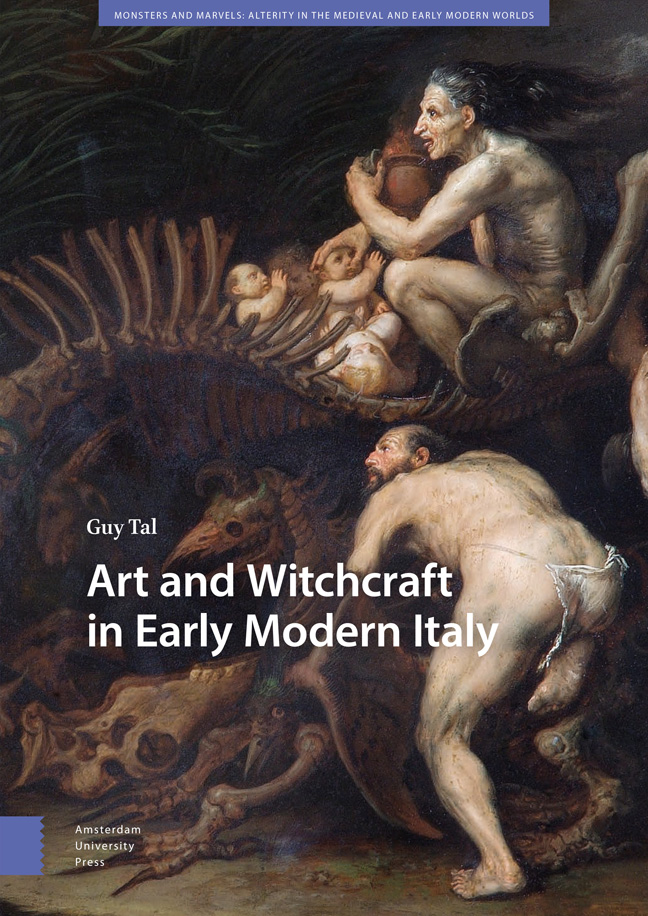

Abstract: The chapter explores monstrosity, heresy, and inversion as the prime trajectories of the subverted world of witchcraft through an analysis of Lo stregozzo, the celebrated engraving of a phantasmic parade presided over by an infanticidal naked crone, produced by Marcantonio Raimondi or Agostino Veneziano in the mid-1520s. The study centers on the visual complex formed by the arresting hybrid monster surmounted by a crouching man. While the inclusion of these two figures defies an iconographical explanation, framing the engraving in the artistic processes of imitation and invention recasts them as a means of thinking about witchcraft and art. Thus, the chimera incites reflection on visual eclecticism, while the crouching man is a sophisticated emulation of Michelangelo's Sistine God.

Keywords: invention, imitation, heresy, God, Devil, hybrid

Almost two centuries after Lo stregozzo (fig. 17) was engraved, Carlo Cesare Malvasia extolled it as one of the finest, most celebrated prints in history. In Felsina pittrice, his 1678 account of Bolognese painters, Malvasia asserted that Agostino Carracci's large engraving The Adoration of the Magi after Baldassare Peruzzi's cartoon was “on an equal level to the most renowned prints, even The Massacre of the Innocents and the Stregozzo by Marcantonio.” While Malvasia's approbation of Marcantonio Raimondi, the Bolognese engraver to whom he dedicated a full chapter, is unsurprising, it is nevertheless remarkable that he elevated a print depicting witchcraft to the same exalted rank as two prints on biblical themes. Aside from Malvasia's acclamation, a lucid testimony to the enduring renown of the Stregozzo is provided by Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, who as an art theorist was intent on acknowledging its inventiveness. In a similar admiration stood the artists who copied it into painting (fig. 19) and recognized it as a source of inspiration (fig. 29). Indeed, the Stregozzo has all the prerequisites to elicit admiration. The original subject matter, merging ideal nudes and inventive monsters, is magnificently displayed through nocturnal effects achieved by tonalities of light and shade, an all’antica relieflike composition, and an exquisite craftsmanship of intaglio (engraving).

Engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi (ca. 1470/82–ca. 1534) or Agostino Veneziano (ca. 1490–ca. 1540) after a design by an unknown artist, the print displays a whimsical parade fervently wending its way in the dead of night along a marshy stretch.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Art and Witchcraft in Early Modern Italy , pp. 81 - 130Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023