While in the 1970s and 1980s Egypt witnessed the growth of one of the strongest Islamist social movements in the Muslim world, it was in neighboring Sudan that the Muslim Brotherhood realized their greatest ambition: controlling the levers of state power and setting themselves up as a model for Islamist movements abroad. After capturing the state in 1989, leaders of Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood actively supported groups elsewhere; they helped plan a failed military coup in Tunisia, met with officials of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and the militant Islamic Group, financed scholarships for members of Somalia’s Islamic Union (al-Ittihad), and offered safe harbor for the leader of al-Qa‘ida, Osama bin Laden. Moreover, because Sudan’s Islamist regime rapidly developed contentious relationships with many conservative Arab states, Khartoum provided tacit support for Islamist militants targeting the violent overthrow of rulers in these states, including the Shi‘i Hizbullah movement and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Indeed, by the time Bin Laden moved al-Qa‘ida to Sudan in 1992, a number of Islamist militant organizations had established training camps outside greater Khartoum.1

The Puzzle of the Sudanese Islamists’ Success

Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood, through its political party, the National Islamic Front (NIF), was buttressed by a formidable economic base and supported by a particularly advantaged social group, making it well placed to assume power. In 1989, on the eve of the disintegration of the state in Somalia and the violent conflict between the Egyptian state and Islamic militants in that country, Sudan experienced an Islamist military coup. The members of the military junta that seized power on June 30 were practically unknown to the public, but from the outset, their ties to the NIF were evident.

The fact that the Muslim Brotherhood was able to enjoy such success in Sudan presents a puzzle. One of the largest countries in Africa, Sudan has more than 500 different tribes speaking as many as 100 different languages, making it perhaps the most heterogeneous country in both Africa and the Arab world. In Sudan, religious cleavages are as pronounced as ethnic ones. Prior to its partition in 2011, the archetypical division was one between an Arab Muslim population in the north and a southern population that subscribes to Christianity and indigenous African religions. In reality, the picture is even more complex. Historically, northern Muslims have tended to identify themselves along Sufi sectarian cleavages, while southerners harbor strong tribal affinities. These cultural, ethnic, and religious cleavages are further compounded by the long-standing hostility of southerners to Muslim Arab domination. Moreover, orthodox and more literal, “fundamentalist” Islamic doctrines have played a limited role as sources of political mobilization or ideological inspiration. In the wake of the coup, many Sudanese asked the same question famously posed by the country’s most prominent writer, the late al-Tayyib Salih: “[F]rom where have these [Muslims] hailed?”2

Solving this puzzle requires examining the historical and economic factors that enabled the Muslim Brotherhood to achieve political dominance. It also requires examining why it was the Muslim Brotherhood, rather than other movements such as the Communist Party, that gained a foothold in politics. While some scholars have attributed the rise of Islamist politics to the increased attractiveness of Islamist ideas to a newly urbanized, frustrated, and alienated civil society, in the case of Sudan this analysis fails to explain the decline of other forms of religious identity, such as popular Sufi Islam, as the basis of political mobilization.3

The story of the Muslim Brotherhood’s assumption of state power in 1989 begins in large part with the monopolization of informal financial markets and Islamic banks by a coalition of a newly emergent Islamist commercial class and mid-ranking military officers. This monopoly endowed the Muslim Brotherhood with the financial assets needed to recruit new adherents from an important segment of the military establishment and from civil society more generally. In the process, and in a tactical alliance with the then dictator, Ja’afar al-Nimeiri, the Brotherhood managed to exclude rival groups and to establish a monopoly of violence in the country. This allowed the Islamists, under the leadership of Hassan al-Turabi, to provide a wide range of material incentives to many middle-class Sudanese. Moreover, following the Islamist-backed military coup of 1989, the ruling NIF used coercion and violence to implement a new set of property rights that maximized the revenue of its Islamist coalition and served to consolidate its political power.4

Sudan and Egypt’s Divergent Political Paths

Economic and political developments in Sudan originally paralleled those of its northern neighbor. As in Egypt, the surge of labor remittances in the wake of the 1970s oil boom circumvented official financial institutions and fueled the expansion of an informal currency trade. The Muslim Brotherhood successfully monopolized the remittance inflows sent by Sudanese working abroad and quickly established a host of Islamic banks, and Sudanese currency traders used their knowledge of the informal market in foreign currency to channel expatriate funds to the new banks. These business relations became particularly profitable after the state lifted most import restrictions, allowing merchants to import goods with their own sources of foreign exchange. The Muslim Brotherhood’s monopolization of informal banking and finance led, as it did in Egypt, to the rise of a distinct and self-consciously Islamist commercial class.

It was in Sudan, however, that the Muslim Brotherhood was first able to transfer this economic leverage into formidable political clout, taking hold of the levers of state power and eventually, under the leadership of Hassan al-Turabi, successfully pressing for the full application of Islamic law (shari‘a). This contrast to Egypt reflects the relative weakness of Sudan’s state capacity and formal banking system. In Sudan, the financial power of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose profits from lucrative speculation in informal market transactions and advantageous access to import licenses further aided by an uninterrupted overvaluation of the Sudanese pound, continued to increase in relationship to the state. It was this financial power vis-à-vis an increasingly bankrupt state that enabled the Muslim Brotherhood to cultivate a constituency far stronger in influence than their rivals in civil society. By the 1980s they successfully utilized this economic leverage to build and expand a well-organized coalition of supporters among segments of the urban middle class, students, and a mid-ranking tier of the military establishment.

A Weak State and a Divided Society: Colonialism’s Dual Legacies

British colonial rule in Sudan left the aspiring state builders of the postcolonial era the dual legacies of a weak state and institutionalized ethnic and religious divisions. In the 1920s the British, partially in response to the threat of the emergence of nationalism in Egypt, inaugurated a strategy of “indirect rule.” This policy devolved administrative and political powers to tribal sheikhs. More importantly, Sufi religious leaders were given greater room to organize in the hopes that a reinvigorated Sufi sectarianism would divide a population that might otherwise unite around national politicians. This British political and financial patronage, combined with the hasty manner in which London negotiated the independence of Sudan in 1956, greatly boosted the fortunes of certain Sufi sectarian and tribal leaders in the north as a result of the pursuit of a “separate development” policy vis-à-vis the south. As an Arab-Islamic identity consolidated in the north, in the south, the influence of Christian missionaries, who under British sponsorship provided educational, social, and religious services, resulted in the development of a Christian and African identity that came into conflict with the political elite in Khartoum. In combination with uneven economic development, and Islamicization policies by northern political leaders vis-à-vis the south, this triggered the four-decade-long civil war in the country.5 They also laid the groundwork for the eventual political success of the Islamist movement in the country.

British economic development focused on cotton production, which was concentrated in the north-central portion of the country – primarily in the fertile lands between the Blue Nile and White Nile south of Khartoum, but also in central Kurdufan to the west and Kassala province in the east. Economic transformations brought three distinct social groups – tribal leaders, merchants, and Sufi religious movements – into positions of economic strength. The latter, organized in the form of “modern” political parties, would dominate civilian politics in the postindependence era as representatives of the economic and political elite.

In the hope of indirectly administering the colonial state and effectively governing the general Sudanese population, British administrators were authorized, in the words of the governor general Lord Kitchener, “to be in touch with the better class of native,” which they accomplished through the distribution of land and assets.6 Most prominent among such beneficiaries were the families of ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, leader of the Ansar Sufi order (tariqa, plural turuq), and ‘Ali al-Mirghani, leader of the Khatmiyya Sufi order.7 British patronage enabled the Ansar to monopolize productive agricultural lands and develop large-scale pump and mechanized agricultural schemes.8 Similarly, it enabled the Khatmiyya to consolidate its economic power in the urban areas of the northern and eastern regions, where its control of retail trade was the basis for the formation of a commercial bourgeoisie. Because these Sufi orders wielded substantial economic power, a large segment of Sudan’s intelligentsia and wealthier merchants organized politically around the al-Mahdi and al-Mirghani families.9 The Ansar sect – which organized under the banner of the Umma Party in 1945 – drew its support mainly from the subsistence agricultural sector and from tribes in the western and central regions of northern Sudan. The Khatmiyya sect – which later organized under the banner of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – dominated Sudan’s merchant community and especially the increasingly lucrative export-import trade in gum Arabic, livestock, and oilseed, drawing support from tribes along the Nile in the north and around Kassala in the east.

In Sudan the structure of the Ansar and the Khatmiyya orders allowed them to take full advantage of British financial support. Both were highly centralized with all contributions and dues flowing to a single leader or family (in contrast, e.g., to the decentralized Qadiriyya and Shadhiliyya orders). Moreover, leaders of both the Ansar and Khatmiyya were involved in the economy (in contrast to the Shadhiliyya leaders, who viewed their role primarily in terms of spiritual and doctrinal services).10 Perhaps most importantly, members of both orders resided in areas where incomes were rising and so they could afford to make significant contributions: the members of the Ansar sect lived in the fertile Gezira plain while followers of the Khatmiyya resided mostly in the semi-arid eastern regions of the country.

By the late 1920s, Ansar leader ‘Abd al Rahman al-Mahdi was enjoying an income of more than 30,000 British pounds annually and, furthermore, had begun to establish wider contacts among educated Sudanese, hence translating his impressive economic weight into political leverage.11 Khatmiyya leader ‘Ali al-Mirghani responded to al-Mahdi’s tactics by patronizing another segment of the Sudanese educated classes in a similar manner. Both families hoped to use these recruitment mechanisms to shape the postindependence political objectives of the university graduates and urban middle class in Khartoum and other urban towns. Having emerged as a central part of the Sudanese commercial establishment, they moved quickly to acquire an equally strong impact on any future political power-brokering in the country and in so doing, to safeguard and further promote their economic prestige.

Ultimately, British colonial policies resulted in deep ethnic and religious divisions in Sudanese society and the emergence of a relatively weak central state in terms of its rulers’ ability to maintain (and sustain) political order, pursue policy autonomous from social forces in civil society, exert legitimate authority over the entirety of its territories and diverse population, and extract revenue from the domestic economy.12 In particular, the ways in which colonial and postcolonial rulers have sought to generate state revenue have had important implications for the way that Sudanese society has made demands on the state and the capacity of the state to exert control over society. That Sudan possessed a weak state was clearly evident by the fact that, since colonial times, a leading feature of the economy was the extensive role of the state in shaping production and generating revenue. Specifically, through the establishment of the Gezira Cotton Irrigation Scheme in the 1920s, the colonial government was able to significantly alter agrarian activities toward cotton exports and essentially build the fiscal basis of the state on financial linkages to international commodity markets. As in other African countries, the British also established a government marketing board that held a legal monopsony on the procurement and export of cotton. In this process of indirect taxation, the board (as the sole buyer) obtained cotton from Sudanese farmers at prices below open market rates and retained the surplus realized upon export. Consequently, as a result of the global demand for cotton at the time, the colonial state enjoyed a healthy budgetary surplus that belied its underlying vulnerability and economic dependence.13 In 1956, on the eve of independence, the Sudanese state generated almost 40 percent of its total revenue from nontax sources. The modern industrial and commercial sector contributed 43.6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and the traditional sector, 56.4 percent. Nevertheless, the state’s extractive capacities, and consequently fiscal health, were almost exclusively based on direct government intervention based on the state-run commodity board, and not taxes on non-state industry or private enterprise.14 Moreover, although these funds were ostensibly intended to promote rural incomes and development in the outlying, economically marginalized, regions in the country, there were commonly diverted to the state bureaucracy and administration or urban infrastructure as a key source of political patronage for incumbent rulers.

The Rise and Durability of Sufi Politics

While colonial policies were formative in influencing the trajectory of state-society relations in Sudan following independence, the unique dynamics of Islamic politics in the country are deeply rooted in the precolonial as well as the colonial history of Sufism in the country. The dynamic of Sufi support for regime politics and the state’s patronage of Sufi orders reemerged in the colonial and postcolonial period as one of the important features of Sudanese political life. Indeed, it goes some way toward explaining the durability of Sufism in Sudanese politics, even as they lapsed into obscurity in other Arab countries. Michael Gilsenan, for example, has noted the sharp decline of Egyptian Sufism (at both the spiritual and political level) since its height in the late eighteenth century. He attributes this to the orders’ inability to respond to a centralized Egyptian state. As he has carefully observed, many of the social functions the Sufi orders used to perform (i.e., charity, job placement, education) were taken up instead by various government agencies. Unable to offer any material goods or services beyond what the state was making available, nor to articulate a unique ideology that would distinguish them from other Muslim groups, they were pushed into retreat. In contrast to Sudan where, thanks to the policies of successive governments, Sufi orders were allowed to assume social functions, in Egypt the traditional functions of the Sufi orders were taken over by other groups and agencies, whether of the state, other voluntary associations, or the religious and intellectual elites.15 Indeed, whereas by the late eighteenth century Sufism in Egypt declined as a result of the Sufi orders’ inability to respond sufficiently to the rise of a strong centralized state, in Sudan Sufi orders survived (and thrived) precisely because of the patronage of local rulers.

Since the nineteenth century, Islam in Sudan has been of an eclectic, diverse, and highly popular variety. Muslim missionaries who came to Sudan from Egypt, the Hijaz, and the Maghrib in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries brought with them the Sufi orders. By the early 1800s, these orders had become the most profound and pervasive form of religious – and political – influence in the country. It was Sufism, rather than the more orthodox Islam of the “ulama,” that was institutionalized. Moreover, prior to independence, leaders of the more influential orders were key agents of social change, engineering a number of revolts, first against Turco-Egyptian rule and later against the British colonizers.

The great influence of Sufi Islam across the centuries made for the relatively slow growth of the orthodox Islamist movement in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Indeed, until the 1970s, the processes associated with modernization did not engender recourse to a fundamentalist doctrine among the majority of Sudanese. Previously the public, cognizant of the harmful effects of colonialism and the corruption of postcolonial leaders, had sought political refuge within their varied sectarian identities vis-à-vis the different Sufi orders. Perhaps more importantly, as noted earlier, the dominance of Sufi political parties until the ascendancy of the Islamists in Sudan in the 1970s can, to a large extent be attributed to the relative weakness of the Sudanese state. During both the Turco-Egyptian period and the British colonial government, the state was heavily dependent on the institutional capacity and popular legitimacy of the Sufi orders, in particular the Ansar and the Khatmiyya. This is a dynamic that would carry over into the postcolonial period and partially explains the swift rise to power of the Islamists.

This is not to say that orthodox Islam had no institutional foundation in Sudan until the Islamist movement emerged ascendant. The Turco-Egyptian conquest of the country in 1820–1821 had brought the shari‘a, which previously had played only a minor role in Sudanese life, although nominally the people adhered to the Maliki School of Islamic jurisprudence (madhhab). Tribal and popular Islamic custom was in most respects the effective law. The Egyptian administration established a formal hierarchy of qadis and muftis within the context of a system of religious courts designed to administer shari‘a according to the Hanafi school. They also built a number of mosques and facilitated the education of a significant number of Sudanese “ulama.”

The remote and legalistic religion of the “ulama,” however, could not easily constitute a living creed for the majority of the population and especially not for the rural Sudanese, distant as they were from the big mosques of the great cities. By putting forward “paths” (turuq) whereby individuals could attain an experience of God, Sufism, named after the simple wool (suf) clothing worn by traveling holy men, filled an important human need. And as more than one historian has noted, the intellectual austerity of orthodox teaching in Sudan seems pale compared to the emotional vigor and vitality of the Sufi orders.16

The popularity of Sufism throughout northern Sudanese history repudiates the contention that Islamism offers a unifying indigenous identity for many Muslims who, in feeling slighted by Western domination and cultural penetration, have increasingly sought in it a moral, political, and even economic refuge. What is clear, at least in the Sudanese case, is that throughout the periods of Turco-Egyptian rule and British colonialism, orthodox Islam did not play a formative role in determining the nation’s economic and political fortunes. What factors, then, contributed to the ascendancy of the Muslim Brotherhood and enabled it to usurp the political authority of the hitherto dominant sectarian Sufi leaders?

The Conflict over Sudanese Islam: Recruiting “Modern” Muslims

By the 1940s, and in the context of the emergence of Sudan’s anticolonial nationalist movement, a number of educated Sudanese youth had begun to seek alternatives to the political dominance of the two most powerful Sufi-backed political parties in the country, the Ansar-led Umma Party and the Khatmiyya-led Ashiqqa’ Party (later the DUP). These youths understood that the leadership of both these orders had been opposed to the anticolonial movement in the country and that they had greatly profited from British patronage.17 The established leadership, in the view of the politicized youths, pursued self-aggrandizing economic interests rather than nationalist objectives.

Two alternatives for political organizing emerged at this time: the Communist Party of Sudan (CPS) and the Muslim Brotherhood. Although the Muslim Brotherhood has been active in Sudan since the mid-1940s, when a number of students influenced by the Islamist movement in Egypt were returning to the country, the movement’s leadership had yet to offer a concrete blueprint for a modern Islamist movement. When in 1949 the leadership of the nascent Islamist movement decided to form a political party, this was done primarily as a reaction to the influence of the Communists in the nationalist student movement. In March of that year, a schoolteacher, Babikir Karrar, formed the Islamic Movement for Liberation (IML), which espoused vague notions of Islamic socialism based on shari‘a. The IML’s main concern at this time as in later years was the rejection of the CPS, which was then the dominant political organization at University College Khartoum.18

In 1954, a divergence erupted within the IML over the primacy of political objectives, with Babikir Karrar and his supporters maintaining that the organization’s emphasis should be on the spiritual awakening of the people prior to attempting political activism. It was this point of debate that led to the creation of two separate organizations: the Islamic Group, led by Babikir Karrar, and the Muslim Brotherhood, led initially by Rashid al-Tahir and later in 1964 by Hassan al-Turabi, who received his doctoral degree in law from the Sorbonne in Paris and whose father was a respected shaykh from a small town north of Khartoum.

Gifted with a high level of political sophistication, which often prevailed over his professed religious scruples, al-Turabi was able to make the Muslim Brotherhood a crucial part of Sudanese politics. By al-Turabi’s own admission, the social base of the movement in its first nine years was limited to students and recent graduates in order to retain the intellectual quality of the movement.19 Al-Turabi and other leaders of the movement had long known that they made up a new and unique phenomenon in Sudanese politics, and for this reason they thought it “undesirable to dilute the intellectual content of the movement by a large-scale absorption of the masses.”20 They were quite aware that the dominance of Sufi religiosity in the country precluded their particular fundamentalist and more militant brand of Islam from developing into a mass movement. At best, particularly in the formative period of their movement, they hoped to recruit people away from the sects and to give them an alternative to their sectarian identities. Yet they also believed that in order to succeed they must at all costs do away with any other alternatives put before the people, which until the 1970s was the CPS.

The growing influence of the Communists under the regime of Ibrahim ‘Abbud (1958–1964), and particularly their dominant role in the October 1964 revolution ousting that regime and in the subsequent transitional government, necessitated a change in the Muslim Brotherhood’s tactics. Specifically, the Brotherhood decided to begin, for the first time, some kind of mass organization in order to participate in the upcoming elections.21 In 1964, they formed the Islamic Charter Front – the forerunner of the NIF – with Hassan al-Turabi as its chairman. Al-Turabi’s strategy was to form political alliances with other traditional forces, which more often than not was the Umma Party, with a view toward achieving two objectives: first, to isolate politically and then to ban the CPS; and second, to utilize the Islamic sentiments of the people to campaign for an Islamic constitution based on shari‘a.22 These objectives were obstructed in May 1969 by the imposition of a pro-Communist regime led by J‘afar al-Nimairi. Predictably, the Muslim Brotherhood opposed the regime and along with its frequent ally, the Umma Party, formed an opposition front in exile.

Al-Nimairi’s suppression of the CPS following a Communist-backed coup attempt in 1971 greatly enhanced the fortunes of the Islamists’ newly named National Islamic Front (NIF) which, along with the Umma party, had by July 1977 entered into a “marriage of convenience” with the Sudanese dictator. In that year, al-Nimairi had embarked on a process of reconciliation whereby he restored to the traditional parties as well as to the Muslim Brotherhood the right to participate in the political process – provided, of course, that they exercised this right within the existing one-party system. More specifically, Nimeiri allowed the two parties to field individual candidates but only as members of the regime’s ruling party. In return, the Umma Party and the Muslim Brotherhood agreed to dissolve their opposition front.

The political benefits of this compromising approach became unmistakably evident as time passed. By the autumn of 1980, the NIF was sufficiently well organized to gain a substantial number of seats in the elections for a new people’s assembly, and al-Turabi himself was appointed the country’s attorney general.23 The motivation behind al-Nimairi’s open co-optation of the Brotherhood at this time stemmed primarily from his perceived need to outflank the Sufi-led political movements, which continued to hold the allegiance of the majority of northern Sudanese. For its part, the Muslim Brotherhood naturally welcomed these developments as an opportunity to enhance its political and organizational strength. Indeed, during this time its membership greatly increased not only in prestige but also in sheer numbers, so much so that by the early 1980s it was no longer the marginal movement it had been during the first twenty years following independence. The political ascendancy of the Islamists quickly brought them into political conflict with the Sufi orders. This clash between Sufism and Islamism, however, is due to political and sociological differences rather than deep cultural animosity. More specifically, Sufis and Islamists in Sudan came to represent different social constituencies jockeying for control over the state and its institutions. Whereas the Sufi brotherhoods span multiple classes and geographic regions, the Muslim Brotherhood’s core support is in the urban areas and among people with higher-than-average education.

Labor Remittances and Islamic Finance in the Boom

During the post-1973 period, international factors greatly influenced the development of Islamic business in Sudan spearheaded by the Muslim Brotherhood opening the way for its rising power in Sudanese political and social life. The Muslim Brotherhood’s greatest strength lay in the two sections of Sudanese society that formed its support base. The first was its constituency of secondary school and university students, particularly in the capital and the more urbanized towns. During the 1970s, a large number of its supporters became teachers in the western and eastern provinces, which fostered major support for the movement there. When these students went on to universities in Khartoum, they came to dominate student politics to such an extent that Brotherhood candidates, until 2008, routinely swept student union elections. The second and perhaps more important base was drawn from the urban-based small traders, industrialists, and new commercial elite. They opposed the traditionally powerful Sufi-dominated merchant families primarily because the latter stood in the way of their own economic aspirations.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s influence in civil society did not, however, translate into the ability to capture state power until global economic factors altered Sudan’s political economy in particular ways. The oil boom in 1973, which saw a corollary boom in both the inflow of labor remittances from Sudanese workers in the Gulf and investment capital from Arab oil-producing states, aided the fortunes of the new Islamist commercial class, which ingeniously translated the economic opportunity into political clout. As the prestige and popularity of the prominent Sufi families declined, an increasing number of youths joined “al-Turabi’s Revolution.” Fueled by incoming remittance capital, the informal foreign currency trade expanded. This expansion simultaneously helped to dismantle the extractive institutions of the state and to erode the last vestiges of traditional sectarian authority in the private sector.

As the Arab oil-producing states, aided by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) price hikes in the mid-1970s, accumulated enormous profits in the oil boom, Sudan came to figure prominently in their long-term development plans. More specifically, they became extremely interested in overcoming their reliance on the outside world for food, and they identified Sudan as the potential “breadbasket” of the Arab world. Initially large amounts of foreign assistance from the Gulf enabled the Sudanese state to fill external and internal resource gaps and strengthen formal institutions. Between 1973 and 1977, for example, over USD 3 billion in foreign loans were committed, and the government’s development expenditure rose from SDG 17 million in 1970 to SDG 186 million in 1978.24

During this period, the state, envisaging large inflows of foreign capital from Arab countries, liberalized key sectors of the economy to lure foreign investment. This took the form of privatization of certain areas of foreign trade and the financial sector. Far from improving Sudan’s formal economy, however, the flurry of development in the mid- and late-1970s deepened economic woes and regional and ethnic grievances. Deficient planning, a rising import bill resulting from escalating fuel costs, and pervasive government corruption characterized by prebendal policies trapped Sudan in a vicious cycle of increasing debt and declining production. Between 1978 and 1982, foreign debt rose from USD 3 billion to USD 5.2 billion. In 1985, when al-Nimairi was ousted, the debt stood at USD 9 billion, and by 1989 it had grown to an astronomical USD 13 billion. While this debt is not overly large by international standards, Sudan’s debt-service ratio amounted to 100 percent of export earnings – making Sudan one of the most heavily indebted countries in the world.25

Equally ominous was the fact that regional inequalities, institutionalized during the colonial era, were now dangerously politicized. Between 1971 and 1980, more than 80 percent of all government expenditure was centered on pump irrigation schemes in Khartoum, the Blue Nile, and Kassala provinces, with little distributed in other regions and almost none going to the south. Moreover, by 1983, only 5 of the 180 branches of the country’s government and private commercial banks could be found in the three southern regions of Bahr al-Ghazal, the Upper Nile, and Equatoria.26 It was within this context that Khartoum’s imposition of shari‘a in 1983 and its desperate efforts to secure revenue from the discovery of oil in the southern town of Bentiu precipitated the rebellion of the southerners of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), ushering in the second phase of civil war. Under the leadership of John Garang, the SPLM rejected the imposition of Islamic law at the federal level and accused the Arab-dominated regime of Nimeiri of seeking to monopolize the oil resources of the south.

By the late 1970s, external capital inflow, and Arab finance in particular, declined rapidly. Government revenues plummeted, forcing the state to increasingly resort to central bank lending. To make matters worse, as the economy began to experience severe inflation and balance-of-payments problems, the economic crisis was compounded by a decline in exports from 16 percent of the GDP in 1970–1971 to 8 percent of the GDP by the late 1970s.27 This was also a period of industrial decline. The large capital inflows that financed a 50-percent increase in public sector investment caused inflationary pressures that hiked the price of imports leading to a sharp decline in the supply of essential goods and inputs from abroad. This, combined with the lack of changes in Sudan’s production system and worsening income distribution patterns, resulted in a stagnating industrial sector.28 Moreover, breadbasket plans favored large-scale and capital-intensive industrial ventures at the expense of the small- and medium-scale firms.

With the formal economy in shambles, a boom of another sort mushroomed, concentrated almost exclusively in the parallel market and fed by remittances from the millions (3 million by 1990 estimates) of Sudanese who, beginning in the mid-1970s, had for economic reasons migrated to the Gulf states. These largely skilled and semi-skilled migrants maximized their own income working in oil-rich states, and moreover, they greatly contributed to the welfare of key segments of the population back home.29 As late as 1985, formal remittances represented more than 70 percent of the value of Sudan’s exports and over more than 35 percent of the value of its imports.30 Labor had become Sudan’s primary export.

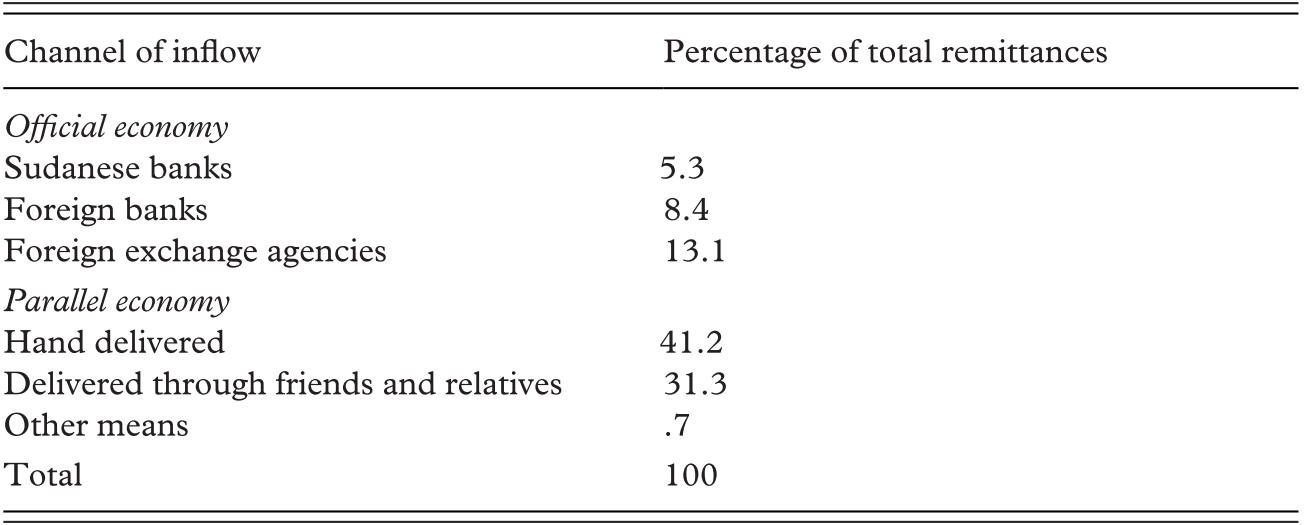

As in Egypt during this same period, the capital accruing from remittances came to represent a financial as well as a political threat to state elites primarily because it came to rest in private hands. The formal record vastly under-represents the true magnitude of these external capital flows because most transactions took place in the flourishing but hidden parallel market (Table 2.1). The balance of payment statistics from the International Monetary Fund, for example, accounts for less than 15 percent of the earnings reported by the migrant workers themselves. Some estimates set the value of fixed and liquid assets of workers in the Gulf close to USD 10 billion – most of it channeled through informal networks.31 Between 1978 and 1987, capital flight from Sudan amounted to USD 11 billion, roughly equivalent to Sudan’s entire foreign debt.32

Table 2.1 Channels of remittance inflows from expatriate Sudanese to Sudanese financial markets, 1988

| Channel of inflow | Percentage of total remittances |

|---|---|

| Official economy | |

| Sudanese banks | 5.3 |

| Foreign banks | 8.4 |

| Foreign exchange agencies | 13.1 |

| Parallel economy | |

| Hand delivered | 41.2 |

| Delivered through friends and relatives | 31.3 |

| Other means | .7 |

| Total | 100 |

Note: In 1986 it was estimated that the total value of expatriate remittances was as high as USD 2 billion. Assuming a similar value for 1988, it can be approximated that USD 1.5 billion entered Sudan through the parallel market that year. “Qimat Tahwilat al-Sudaneen fi al-Khalij ithnayn miliar dollar amriki,” [The Value of Remittances of Sudanese in the Gulf is Worth 2 US Billion Dollars], Al-Majalla, June 11, 1986, 31.

Approximately 73 percent of this capital inflow was channeled through informal financial intermediaries or relatives, 18 percent through state-run banks and foreign currency exchange agencies, and 8 percent through foreign banks (see Table 2.1). Most of these remittance (73 percent of the total remittance capital inflow) assets were quickly monopolized by the small but highly organized Islamist commercial class, which organized under the NIF, captured huge “scarcity rents” in foreign exchange through the manipulation of parallel market mechanisms – that is, through control of the black market, speculation in grain, smuggling, and hoarding.33 Since at the time many Islamists had access to state office under the Nimeiri regime, they were able to use state institutions to monopolize the inflow of remittances. Indeed, by bridging the divide between illicit, parallel, and formal markets, the Islamists gained preferential access to foreign exchange, bank credits, and import licenses.

The transactions in the burgeoning parallel market were centered in urban areas. This naturally meant that capital flowed into the private sector in a manner that compensated many urbanites for declining income-earning opportunities. More importantly for Sudan’s political economy, however, these transactions weakened the state’s ability to extract revenue in the form of foreign exchange. In particular, the state’s capacity to tax greatly diminished, and the state came to rely more and more on custom duties and other forms of indirect taxation. This was especially true in the agricultural sector. The ability of the state to extract revenue from this potentially lucrative sector of the formal economy had been substantial prior to the mid-1970s, averaging 20 percent of the state’s annual revenue. But by the mid-1970s, direct taxation declined considerably, averaging less than 10 percent per year before dropping to 4 percent by 1987–1989. As early as 1975, indirect taxation accounted for five times that of direct taxation. The extent of indirect taxation, in the form of customs and import duties, increased steadily from less than 20 percent of total state revenue (excluding grants) in 1973 to 55 percent in 1980.34 The effects of such a dramatic boom in informal capital inflows in eroding the capacity of weak states to generate taxes and regulate domestic economies are common among the labor-exporting countries in the Arab world. As one scholar of remittance economies has noted in the case of Yemen, for example, “the narrow basis of state revenues cultivated in the boom ensures that state coffers are depleted in the recession period as expendable income and imports and customs duties drop.”35 In Sudan, the political battle over foreign currency and the monopolization of rents garnered from the parallel market and import licenses came to occupy the energies of both state elites and groups in civil society. Various actors vied for the economic and political spoils that they correctly perceived would accrue to the “victor.” Disputes among state elites over monetary policy fostered a factionalism that caused many a cabinet reshuffle.

The structural transformation engendered by the parallel market also drastically altered the country’s social structure. The traditional private sector, which consisted primarily of the landed Ansar elite and the Khatmiyya of the suq (traditional market), was devastated by the state’s “shrinkage” since it had in large part relied on the state’s largesse, particularly in the early part of the Nimairi regime. Consequently, whereas in the first two decades of the postcolonial state, Sudanese civil society was dominated by the sectarian patrons and their clients, by the late 1970s Sudan’s private sector was separated into two social groups: those who profited from transactions in the parallel market and state elites and bureaucrats whose survival was contingent on capturing as much hard currency as possible before it was absorbed by this hidden economy.

The first group included the workers who had migrated to the Gulf. Their remittances, in turn, produced the economic clout enjoyed by financial intermediaries known as suitcase merchants (tujjar al-shanta) who bought and sold hard currency in the parallel market. A broad spectrum of the Sudanese petit bourgeoisie, cutting across ethnic and sectarian cleavages, engaged in these transactions, but the industry was effectively monopolized by five powerful foreign currency traders with close ties to Islamist elites.36 The second group consisted of the central bank and other governmental authorities responsible for official monetary policy. Their priority was to attract private foreign capital from nationals abroad. Commercial banks likewise depended on attracting this business, and it was to them that al-Nimairi looked to for his political survival.

Islamic Banks as Bridges: Linking Informal and Formal Markets in a Regional Context

By the late 1970s, in search of political legitimacy and the funds with which to finance it, al-Nimairi sought to involve the state in the increasingly autonomous private sector. He saw the Islamic banks, even more than non-Islamic Arab development institutions as the best way to attract more capital from the Gulf while simultaneously garnering much-needed political allegiance of the Muslim Brotherhood. This is because most inter-Arab development funds established by the Arab oil exporters after 1973 stressed less-risky investments in public sector enterprises over private investment. In contrast the more ideologically driven Islamic banks based in the Gulf – created in “accordance to the provisions of shari‘a” – were interested (and mandated) to invest in private enterprises outside the purview of domestic states and state-run banks.37

Established in 1977 by a special Act of Parliament, the Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan (FIBS) was the first financial institution in Sudan to operate on an Islamic formula. In theory, this meant that all its banking activities must adhere to the principles of Shari’a law in which riba (interest or usury) is prohibited and the time value of money is respected. In practice the lending activities of Islamic banks consist of a contract whereby the bank provides funds to an entrepreneur in return for a share of the profits or losses. For his part, in order to encourage the growth of the FIB, and the Islamicization of the financial sector more generally, al-Nimairi altered property rights in a way that afforded the Islamic financial institutions a special advantage over other commercial and government banks, exempting them from taxes and effective state control. Equally important, the Islamic banks enjoyed complete freedom in the transfer and use of their foreign exchange deposits, which meant that they were able to attract a lion’s share of remittance from Sudanese working in the Gulf.38 Under the Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan Act, Faisal Islamic Bank (FIB) enjoyed unprecedented privileges, none of which was afforded to other commercial banks. The FIB was the model upon which all the other Islamic banks in the country were established and operated. It was composed of the general assembly of shareholders, a board of directors, and a supervisory board to ensure that the bank would operate according to shari‘a. FIB was the first of many Islamic banks to be exempted from the Auditor General Act and from provisions of the Central Bank Act concerning the determination of bank rates, reserve requirements, and restrictions of credit activities. Moreover, the bank’s property, profits, and deposits were exempted from all types of taxation. The salaries, wages, and pensions of all bank employees and members of the board of directors and shari‘a supervisory board were likewise exempted.

In December 1983, a presidential committee went further and converted the entire banking system, including foreign banks, to an Islamic formula. Al-Nimairi timed this to outflank the traditional religious and political leaders and secure the allegiance of the Muslim Brotherhood – the only group left that supported him. In short, state intervention and selective financial deregulation transformed Islamic banks into secure, unregulated havens for the deposit of foreign currency earned by Sudanese operating within the parallel market. In this regard, the informalization, or rather deregulation, of these informal financial markets could not have been possible without the patronage and policies of the Nimairi regime who, in the wake of declining legitimacy, was desperately striving to rebuild strong patron-client networks in civil society.

The linkage between the Islamic banks and currency dealers operating in the parallel market became increasingly sophisticated and profitable as the market expanded. The informal currency traders fell into essentially two groups. The first comprised five powerful currency traders, each earning a profit of SDG 1 million annually, who advanced the start-up capital for a second group of approximately 100 mid-ranking financial intermediaries. This latter group, each earning between SDG 200–500 daily, served as direct intermediaries between the expatriate sellers and their families.39 But it was the first-tier currency traders that, owing to their established credibility and knowledge of the urban parallel market, helped channel expatriate funds to the Islamic financial institutions. More importantly, a number of the large currency traders were closely associated with the Islamist movement and members of the NIF.40

These business relations became particularly profitable after the state lifted most import restrictions, which allowed merchants to import goods with their own sources of foreign exchange. This meant that to start a business in Sudan, expatriates and their families had to exchange their US dollars or dinars for local currency. Islamic banks were particularly well placed to buy up these dollars, which they did through dealings with, and at the recommendation of, the big currency traders.41 These Islamic banks had the additional advantage of pursuing an ideological agenda attractive to many wealthy Gulf Arabs, who supported them with large capital deposits. As a result, Islamic banks enjoyed spectacular growth. Faisal Islamic Bank’s paid-up capital, for example, rose from SDG 3.6 million in 1979 to as much as SDG 57.6 million in 1983. Over the same period, FIB’s net profits rose from SDG 1.1 million to SDG 24.7 million, while its assets, both at home and abroad, increased from SDG 31.1 million to SDG 441.3 million.42

As Table 2.2 demonstrates, growth was particularly strong during the oil boom that began in the mid-1970s and lasted through to the early 1980s. Clearly the phenomenal growth of Islamic finance reflected developments in the Gulf, and the tremendous increase in oil prices in the early 1970s, which produced enormous private fortunes in the Gulf countries and provided entrepreneurs with the required capital to invest in Islamic banking. This boom in the Arab Gulf (especially Saudi) financial investment coincided with the sharp rise in the capital stock of Faisal Islamic Bank. In 1980–1981, for example, growth averaged more than 100 percent per annum, almost three times the growth of the other commercial banks. What these figures illustrate is that the financial profile of the Islamist movement, closely linked to its monopoly over the Islamic banks, rose sharply in relation to not only the state-run banks but also other private financial institutions in the country. Moreover, just as al-Nimairi was increasingly starved for funds with which to finance his regime’s patronage networks, the Islamists were able to utilize their new-found wealth to provide economic and financial incentives to an increasingly greater number of supporters among the country’s urban middle class.

Table 2.2 Comparison of the magnitude and growth of private deposits in Sudan’s Commercial Banks (CB) and Faisal Islamic Bank (FIB), in SDG 1,000

| Year | CB deposits | Annual growth rate (%) | FIB deposits | Annual growth rate (%) | FIB deposits as (%) of CB deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 528,805 | − | 21,774 | − | 4.0 |

| 1980 | 694,824 | 31 | 49,512 | 127 | 7.0 |

| 1981 | 856,789 | − | 102,319 | 107 | 12.0 |

| 1982 | 1,305,0444 | − | 202,372 | 98 | 15.0 |

| 1983 | 1,709,015 | 31 | 257,000 | 27 | 19.7 |

| 1984 | 1,964,073 | 15 | 276,000 | 7 | 14.1 |

| 1986 | 3,280,817 | 67 | 293,000 | 6 | 8.9 |

| 1987 | 4,243,712 | 36 | 308,905 | 5 | 7.3 |

| 1988 | 5,786,160 | 36 | 352,310 | 14 | 6.0 |

| 1989 | 7,200,314 | 32 | 493,754 | 40 | 6.0 |

The success of the FIB and its organizational structure was a key model for all the other Islamic banks in the Sudan and it triggered a veritable boom in the proliferation of other Islamic banks in the country. For example, following the FIB model, in 1984 Saudi businessman Shaykh Salih al-Kamil, a shareholder in the Gulf-based al-Baraka Islamic bank, established a branch of this bank in Sudan as a public joint-stock company. Its paid-up capital, provided by al-Kamil, the Faisal Islamic Bank, and other private investors, was USD 40 million. Moreover, the Sudan branch of al-Baraka established two subsidiary companies in Khartoum: al-Baraka Company for Services and al-Baraka Company for Agricultural Development. This process went on as a number of other Islamic banks were established throughout the 1980s, including the Sudanese Islamic Bank and the Islamic Bank for Western Sudan, which like the FIB, specialized in loans to aspiring borrowers looking to start-up small- and medium-sized firms primarily in services and retail businesses.

The Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood saw in the success of the Islamic banking sector an important vehicle from which to achieve its political and economic objectives and outflank its rivals in civil society. Indeed, a striking feature of this growth is the extent to which the majority of the Islamic banks had links with the Brotherhood, and how much the Umma and DUP were left out in the financial wilderness. For its part, the Faisal Islamic Bank was controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood and in particular its leader, the increasingly powerful Hassan al-Turabi.43 This same bank also entered into a joint venture with Osama Bin Laden, creating the Islamic Al-Shamal Bank.44 Al-Turabi utilized much of the FIB’s profits to help finance the Islamist movement. The Tadamun Islamic Bank also had very close links with the Muslim Brotherhood which established a financial empire that included subsidiary companies in services, trade and investment and real estate. The Al-Baraka Investment and Development Company – also, established in 1983 – was completely controlled by a Saudi family; however, the managing director was a leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood. Notably, the Umma Party did not have its own bank.

The establishment of Faisal Islamic Bank, Tadamun, al-Baraka and other Islamic financial institutions also signaled the unprecedented integration of Sudan’s financial markets with those of the Gulf and particularly Saudi Arabia.45 This was clearly evident in the banks’ structure and ownership profile. Indeed, the Faisal Islamic Bank was from the beginning designed to have a broad ownership structure that privileged foreign Muslim shareholders and as such it forged very close links between Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood and Gulf financiers sympathetic to their political objectives.46 In this context, it is important to note that the exiled members of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood belonged to the circle around Prince Muhammad Al-Faisal, and it is because of their influence that he decided to invest in the Sudan and help establish the FIB. The FIB, like other Islamic banks, established an office in Jedda, which accepted deposits from expatriates living in the Gulf; 40 percent of FIB’s capital was provided by Saudi citizens, Sudanese citizens provided another 40 percent, while the remaining 20 percent came from Muslims from other countries, primarily residing in the Gulf states.47

By the mid-1980s, Sudan’s once relatively closed economy had become closely integrated with the global economy. Both state elites and Islamist financiers benefited from their relationship to the expansion of Islamic banking linked to Gulf. Prior to converting the entire banking system in the country to an Islamic formula, the Nimairi regime had invested heavily in this sector. It established state-run banks including the Development Cooperative Islamic Bank (DCIB) and the National Cooperative Union (NCU). Both these banks were financed from funds coming from the Ministry of Finance. Initially state law mandated that all the shareholders in the DCIB and NCU must be Sudanese nationals. However, the regime promulgated the Bank Act of 1982, which, in order to lure Gulf capital, authorized foreign investment in the banking sector including what were hitherto state-controlled national banks. Sudan’s Islamic banks were closely linked not only to prominent government officials, but also to one another. For example, Faisal Islamic Bank and al-Baraka acquired shares in the North Islamic Bank, established in 1990; and the government, together with Arab and other private Sudanese investors, also owned shares in the North Islamic Bank.

Two other key Islamic institutions with global reach established during this time were the Islamic Finance House (IFM) and the Islamic Cooperative Bank of Sudan (ICB). As was the case with most of the other Islamic banks, the IFM and ICB’s ownership was linked to a transnational network of Islamist financiers and investors. Based in Geneva, the IFM continues to have institutions and branches all over the world. Like Faisal Islamic Bank, the IFM was founded by Prince Muhammad al-Faisal of Saudi Arabia, who was also the chairman of the International Association of Islamic Banks.48 It is important to note that the main shareholders of the IFM, besides members of the Saudi royal family, included al-Nimairi and Hassan al-Turabi.49 The ICB was established in the early 1980s and represented the close integration between Sudan’s domestic banking sector and global Islamic financial interests. In addition to its banking activities, ICB owned shares in the Islamic Development Company (Sudan), Islamic Banking System (Luxembourg), and the Islamic Bank for Western Sudan. Its main shareholders were Faisal Islamic Bank, Kuwait Finance House, Dubai Islamic Bank, Bahrain Islamic Bank, and other Arab private investors.

Inclusion through Exclusion: Financing an Islamic Commercial Class

According to FIB officials, a primary purpose of Islamic banks is to provide interest-free personal loans to the general population – in their words, “to ameliorate the suffering of the masses and to present an alternative to interest-based banks, which provide for the ‘haves’ and give little care to the ‘have-nots.’”50 However, the investment pattern of these banks (see Table 2.3) did not translate into a more equitable distribution of income, as many proponents of the Islamic banks claimed. The credit policy of the Islamic banks was clearly designed to build and enhance the fortunes of an Islamist commercial class, and by the 1980s the latter became far more powerful than the hitherto dominant groups in civil society (particularly the Khatmiyya sect, which had dominated the traditional export-import sector in the urban areas) as well as the state. In this context, it is important to note that the Khatmiyya established the Sudanese Islamic Bank in 1983 to compete with the Muslim Brotherhood–dominated banks and the all-important commercial sector. However, since by the late 1970s, the Khatmiyya had fallen out of favor with the Nimeiri regime they were not able to establish any other financial institutions in the country and revive their social and economic base in urban commerce.

Table 2.3 Faisal Islamic Bank (FIB) lending for trade, 1978–1983

| Trade sector | Value, USD ml | No. of clients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Export | 168 | 96 | 48 |

| Import | 119 | 528 | 40 |

| Domestic Trade | − | 298 | − |

As a study of the entire Sudanese Islamic financial system noted, only 6 percent of all lending is allocated to personal loans with the remaining going entirely to commercial enterprises. Furthermore, Islamic banking is characterized by “low lending capacity, regional inequality in the distribution of banking branches, and sectoral concentration of investment and the bias toward the high profitable institutions in the modern sector at the expense of the small sector.”51 The largest Islamic Bank, FIB, for example, made an explicit policy decision to minimize risk and realize profits in “the shortest possible time” by concentrating lending in export-import trade and the “financing [of] small businessmen.”52 By 1983, more than 90 percent of FIB’s investments were allocated to export-import trade and industry and only 0.5 percent to agriculture, thereby ensuring strong support for the Islamists among the middle- and lower-class entrepreneurs.53 Indeed, the declared policy of FIB was “to promote the interests of Sudan’s growing class of small capitalists whose past development has been effectively retarded and frustrated by the dominance and monopolization of commercial banks’ credit in the private sector by traditionally powerful merchants.”54

By concentrating on trade financing, Islamic banks did little to achieve their stated aims of alleviating social and economic inequities. On the contrary, they were widely criticized for profiteering from hoarding and speculation in sorghum (dura) and other basic foodstuffs and, moreover, were accused of exacerbating the famine of 1984–1985. Faisal Islamic Bank in particular came under criticism for hoarding more than 30 percent of the 1983–1984 sorghum crop in the Kurdufan region and, when Kurdufan was hit by drought and famine, selling it at very high prices.55

Moreover, the branches of the Islamic banks, like those of the conventional banks, were located primarily in urban areas and the predominantly Arab and Muslim regions of the country. Despite claims to serve localities neglected by conventional Western-style banks, Islamic banks were no better than conventional banks, whether national or foreign, in breaking the pattern of urban and regional bias established during the colonial period (Table 2.4).

As the figures in Table 2.4 show, more than 80 percent of Islamic banks were concentrated in the urban centers of the Khartoum, east, and the northwestern regions. Moreover, out of 183 branches in operation, as many as 78 (43 percent) were situated in Khartoum. This is more than the total banking facilities found in the five regions whose population overwhelmingly comprises the subsistence sector of the economy and more than 90 percent of the country. Indeed, as of 1988, not one Islamic bank had been established in the south and only one was in the western province of Darfur – the most underdeveloped parts of the country (see Table 2.5).

Table 2.4 Branch distribution of the Islamic commercial banking network in Sudan by region, 1988

| Central/Khartoum | Eastern | Kurdufan | Darfur | Northern | Southern | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of bank branches | 78 | 31 | 30 | 15 | 7 | 11 | 183 |

Table 2.5 Regional branch distribution by type of bank in Sudan with percentage of type of network, 1988

| National | (%) | Islamic | (%) | Foreign | (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khartoum | 44 | 37 | 20 | 46 | 14 | 67 | 78 |

| Central | 24 | 20 | 6 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 31 |

| Eastern | 16 | 14 | 9 | 21 | 5 | 23 | 30 |

| Kurdufan | 12 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 29 |

| Darfur | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Northern | 6 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Southern | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 119 | 100 | 43 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 198 |

The Islamic bankers’ claim that they give priority to rural financing and rural development is belied by the absence, or at best minimal presence, of Islamic banks in the southern and western (i.e., Darfur) regions of the country. These banks were from the beginning driven by business rather than social or religious considerations: Their absence in the south and west can be explained by the absence of appropriate infrastructure and the low prospects of profitability in these regions due to their relative underdevelopment and political instability. In addition, religious and ethnic factors have played an important role: The fact that the south is neither Muslim nor Arab is a key reason why the Islamic financiers have shown both a neglect of – and even a great hostility toward – providing credit to its rural communities.

However, it is just as important to point out that Islamist financiers also targeted a particularly small segment within the Arab-Muslim population in the northern regions of the country. They recruited bank staff and managers based on their support for the movement, and at the level of civil society, they extended credit and financial support to those who had prior links to the Muslim Brotherhood’s Islamist movement.

The Business of Islamist Recruitment

Since the founding of the Islamic banks, there has been a mutual interest between their shareholders and the Muslim Brotherhood. The largest shareholders were primarily merchants of the Gulf who sought religiously committed individuals ready to support the Islamic banks both materially and ideologically. They thus favored well-known Islamist activists and individuals recommended by the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The recruitment of bank staff is designed to ensure commitment and trust within and across these financial institutions. Faisal Islamic Bank’s general manager outlined the pattern of recruitment in the following manner:

The personnel needed by Islamic banks should not only be well qualified and competent but should also be committed to the cause of Islam. They should have a high degree of integrity and sense of duty in dealing with all the operations of the bank. Therefore, their performance and sincerity should not only come from the built-in controls of the system, but also from their religious conscious and sentiment.56

This bias toward Islamist activists for staff recruitment and in matters of distribution and lending meant that Islamic bank beneficiaries were largely urban supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. It has also meant that credit activities became concentrated on a small part of the domestic economy to the exclusion of other segments even of the urban population.

The evidence that the Muslim Brotherhood focused their efforts on providing economic incentives to build an aspirant middle class is clear from the Islamic banks’ lending practices and the use of Islamic financial proscriptions to bolster their patronage links to newly mobilized clients in urban Sudan. The investment encouraged the growth of small- and medium-sized businesses, effectively ensuring support for the Muslim Brotherhood from the middle and lower strata of the new urban entrepreneurs.

Islamic banks in Sudan rely on essentially two methods, or contracts, for the utilization of funds: murabaha and musharaka. Musharaka takes the form of an equity participation agreement in which both parties agree on a profit-loss split based on the proportion of capital each provides. If, for example, a trader buys and sells USD 10,000 worth of industrial spare parts, the bank (while not charging interest) takes 25 percent of the profits and the borrower the remaining 75 percent, assuming an equivalent proportion of capital provision. Importantly, if there is any loss, the bank and the customer share the loss in proportion to the capital they both initially provided. Murabaha, while similar in terms of representing an equity participation contract, differs from musharaka in that the bank provides all the capital while the customer provides his labor. Consequently, if there is any loss the bank loses its capital and the customer loses his labor and time. In essence, murabaha is a contract whereby the bank provides funds to an entrepreneur in return for a share of the profits, or all of the losses, whereas musharaka – participation – is more akin to venture capital financing.

In Sudan, the most common contract has been overwhelmingly murabaha and, because clients usually have to enter into a joint venture for a specific project in order receive funds from the bank, the capital comes with political and economic strings.57 Since the transaction is not based on the formal creditworthiness of the client and there is no requirement of presenting securities against possible losses, the bank officials have a great deal of discretion with respect to whom it lends to. Since the Muslim Brotherhood dominated the staff of the Islamic banks they successfully used credit financing to both support existing members and provide financial incentives for new business-minded adherents to the organization. Thus, for example, an aspiring businessman, to qualify for a loan, must provide a reference from an established businessman with a good record of support for the Muslim Brotherhood.58 This requirement led to almost comic attempts by many in the urban marketplace to assume the physical as well as religious and political guise of Islamists.

For a society in which Sufism had long occupied the most significant space in social, political, and economic life, the dramatic ideological and cultural shift toward Islamism seemed to occur seemingly overnight. But as Douglas North has observed, individuals alter their ideological perspectives when their everyday experiences are at odds with their ideology. Similarly, many young Sudanese men and women who, being denied the resources and social networks crucial for improving their income position in society because of the alteration of “excludable” property rights, became acutely aware that the “more favorable terms of exchange” were to be found in joining the Islamists’ cause.59 As Timur Kuran has noted poignantly, since the 1970s throughout the Muslim world Islamic banking and a wide range of financial networks have helped newcomers who had hitherto been excluded from the economic mainstream and middle-class life to establish relationships with ambitious Islamic capitalists. Indeed, many social aspirant urban residents in Sudan sought in the Islamic banking boom the opportunity for economic and social mobility.60 However, as the lending patterns of the Islamic banks in the case of Sudan show these Islamic financial houses were also clearly interested in the promotion of specific ideological and political objectives. The bulk of the lending was directed toward a small segment of the middle class in the urban areas and strict monitoring of murabaha contracts was enforced in terms of who was to receive a loan and the conditions for repayment. Moreover, as Stiensen has observed, the battle in the boardrooms of the Islamic banks showed that the Muslim Brotherhood actively sought to monopolize these banking institutions and eliminate potential rivals. Specifically, emboldened by the largesse of the Nimeiri regime, the Muslim Brotherhood used its position to recruit members for the movement by hiring them in the banks, and “colleagues known to be critical or hostile to the movement were forced out.”61 The bias in favor of the Muslim Brotherhood did not go unnoticed. Non-Islamist minded businessmen, some of them shareholders, complained that they did not receive finance from the FIB, and audits by the Bank of Sudan revealed that many banks, members of the board of directors, and/or senior management monopolized borrowing, and the default rate of such loans was in general very high.62

If Islamic banking aided the Muslim Brotherhood in building a new Islamist commercial class, the organization also attempted to supplant the traditional Sufi movements in the realm of social provisioning. Specifically, it broadened its political base by financing numerous philanthropic and social services. The most notable of its ubiquitous and varied charitable organizations included the Islamic Da‘wa Organization, the Islamic Relief Agency, and the Women of Islam Charity, which owned a set of clinics and pharmacies in Khartoum. The Muslim Brotherhood also provided scholarships to study abroad to youths who assumed an ardent political posture in its behalf. Moreover, in the context of a very competitive labor market, the Brotherhood actively solicited recent university graduates for employment in Muslim Brotherhood–run businesses. One student from the University of Khartoum rationalized his support for the Muslim Brotherhood in economic rather than ideological terms:

I am not really interested in politics. In fact, that is why I support the Ikhwan [Brotherhood] in the student elections. I am much more concerned with being able to live in a comfortable house, eat, and hopefully find a reasonable job after I graduate. The fact is that the Ikhwan are the only ones who will help me accomplish that.63

Once formally joining the Muslim Brotherhood organization members would also have privileged access to “additional services.”64 Toward this end, Islamic banks and their affiliated companies established a large number of private clinics, private offices, private schools, and mutual aid societies for certain professional groups including medical and legal professionals.65 For example, Faisal Islamic Bank and al-Baraka financed the Modern Medical Center in Khartoum. In the field of transport and food processing, the Muslim Brotherhood established enterprises like Fajr al-Islam Company, Halal Transport Company, and Anwar al-Imam Transport Company, among many others, and in food retail, they established chains including al-Rahma al-Islamiyya Groceries and al-Jihad Cooperative. Of all the Islamic enterprises doing “business” in the cause of Islam, however, the Islamic banks were the most important and had the greatest effects on the society and the economy. The Muslim Brotherhood’s close links with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states meant that there was almost no shortage of cash, even in a country as poor as Sudan. Figure 2.1 neatly illustrates this linkage between the transformation of Sudan’s economy and the ascendancy of the Muslim Brotherhood in the era of the boom in remittances generated from migration to the Arab Gulf.

Figure 2.1 Informal transfers and Islamist activism in the remittance boom in Sudan

Transformation of State Ideology: Nimeiri, Shari’a, and the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan)

Although since assuming power in 1969 the Nimairi regime had a strict secularist stance, as a result of its waning political legitimacy and the rise in the economic power of the Muslim Brotherhood, political Islam came to occupy a significant place in Sudanese social, political, and economic life. Indeed, one of the most important factors in explaining the increasing importance of Islam in Sudanese politics was a major change in Nimairi’s attitude toward Islam and the great extent to which he incorporated the Brotherhood into state institutions in his illusive search for political legitimacy.

In September 1983, al-Nimairi announced the implementation of shari’a in Sudan, making it the only Arab Muslim country to promulgate a wide range of laws that would completely subsume the secular court system into the Islamic judiciary, which up till then had been limited to hearing matters of personal law.66 Al-Nimairi’s promulgation of the September Laws marked a stunning victory for the Islamists, and particularly for Hassan al-Turabi and the Muslim Brotherhood. More specifically, having established a dominant position in the economy, the September Laws marked the beginning of the Brotherhood’s formal consolidation of political power, this time via legal means. In this regard, the political success of Sudan’s Islamists was attributable to the weakness of the ruling regime just as it was to the increasing strength of al-Turabi and the Muslim Brotherhood made possible by the rising financial fortunes of the movement. As noted earlier, over the course of the 1970s, al-Nimairi’s regime had destroyed or alienated all its former political and ideological allies, leaving it with little option than to court the national opposition movements. At the same time, al-Nimairi was eager to claim for himself the mantle of religious and populist legitimacy. Indeed, in 1982 al-Nimairi, whose political orientation and reputation in the 1960s and 1970s were of a hard-drinking military officer more sympathetic to communism than Islamism, proclaimed himself the people’s imam. The promulgation of the September Laws in 1983, therefore, was both an attempt to win support of the Muslim Brotherhood and to establish the religious and populist credentials necessary to shore up a new patron-client network, this time more reliant on the Islamists than the disaffected traditional Sufi-backed political parties of the past.

Interestingly, in many ways, the Sudanese case tracks that of Egypt remarkably closely. Like its northern neighbor, Sudan also experienced major economic upheaval, though somewhat later than Egypt did. While the first half of President Ja’far al-Nimairi’s rule (1969–1985) was marked by economic success, the second half was an unmitigated disaster. Large infrastructure projects, including the expansion of the Gezira Scheme and the Kenana Sugar factory, entailed major injections of foreign capital that drove up inflation rates and saddled the country with high levels of debt.67 Corruption and inefficiencies in the labor market – necessary for al-Nimairi to keep his bureaucracy under control – generated massive amounts of waste at precisely the time when the country was desperate to attract foreign investors. By the mid-1970s, Sudan was saddled with an enormous trade imbalance, largely at the hands of urban elites eager for expensive consumer products from abroad. The problem, according to the noted Sudanese scholar (and former Minister under al-Nimairi) Mansour Khalid, was that al-Nimairi was simply trying to develop the country too quickly.68 His regime’s legitimacy rested in no small part on its aura of competence and effectiveness. The possibility of an economic slowdown, therefore, prompted him to launch an economic program that the country simply could not sustain.

But if in Egypt, the economic crisis of the 1970s created what Rosefsky-Wickham has termed a lumpen intelligentsia sympathetic to Islamist aims, the Sudanese experience is somewhat different.69 During the 1980s, the Mubarak regime in Egypt broadened its base of support to include the businessmen who had benefited from the country’s privatization of industry. Subsequently, Egyptian national politics, before as well as after Tahrir, came to be characterized by a military-business alliance able to successfully split the opposition into unorganized and mutually distrustful camps. In Sudan, by contrast, the opposition has been considerably better organized and stronger by virtue of the relativel weakness of the Sudanese state. Though al-Turabi and many other members of the Muslim Brotherhood were arrested immediately after Nimairi’s coup in May 1969, they were able to reconstitute themselves outside the country not long afterward. Turabi joined up with Sadiq al-Mahdi in Libya and began planning an armed uprising, with the possible support of the Khatmiyya as well. Still, having liquidated the communists in 1971 and signed the Addis Ababa accords in March 1972, al-Nimairi enjoyed widespread support both at home and abroad. The uprising of 1973 against the al-Nimairi regime was an unmitigated disaster for the opposition, as was another joint Ikhwan-Ansar uprising in 1976. To most observers at the time al-Nimairi’s authoritarian regime appeared unassailable, and the institutional and coercive capacity of the state relatively strong.

Appearances, however, were deceiving. By the mid-1970s, Sudan’s economy had begun to stagnate. With economic conditions in Sudan steadily worsening, al-Nimairi sensed that his regime was in peril. Having destroyed the communists some years earlier, he had no choice but reach out to the Brotherhood and the Sufi orders in hopes of achieving some sort of reconciliation. Fortunately, it seems as if the opposition parties were as eager for reconciliation as was Hassan Turabi, who had watched his movement gradually disintegrate over the last decade.70 Talks with Sadiq al-Mahdi seemed to be progressing as well, but eventually fell apart over disagreements concerning the Ansar’s role in government.71

It is at this point that the government’s alliance with the Brotherhood in 1977 was cemented further as evidenced by the timing of the promulgation of the September Laws in 1983. As Mohammad Bashir Hamid has noted, the reintroduction of shari’a in the 1980s was al-Turabi’s price for rejoining the government.72 However, the Brotherhood would not have achieved access to state power if the al-Nimairi regime was not gravely weakened, and he was thus was seeking to rebuild a new, independent base of popular support. This entailed a three-step process. First, the passage of the September Laws allowed al-Nimairi to claim for himself the mantle of religious legitimacy. Beginning in 1972, he had begun regularly attending a minor Sufi order of the Abu Qurun family, which believed that a “second Mahdi” would soon emerge from among its followers and would take up the mantle of leadership for all Muslims.73 Second, the passage of the September Laws was extremely popular with many northern Sudanese Muslims. Even setting aside the Brotherhood, it is clear that for many Sudanese, the reinstatement of shari’a was something worth celebrating. This populist component to the laws is something to which relatively few scholars have given much consideration, preferring instead to focus on their resonance with the country’s Islamists. To be sure, the laws’ popularity extended to many corners of society, including among followers of the Khatmiyya and Ansar.74 That appeal was largely a function of the belief that the shari’a would deliver “prompt justice” (al-‘Adala al-Najiza) to the many Sudanese who felt marginalized and abused by the corrupt economic practices of the urban elite.75